Abstract

Laricobius nigrinus (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) Fender and Laricobius osakensis (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) Montgomery and Shiyake have been mass produced by Virginia Tech as biological control agents for the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), Adelges tsugae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae) Annand, for the past 15 and 9 yr, respectively. Herein, we describe modifications of our rearing procedures, trends and analyses in the overall production of these agents, and the redistribution of these agents for release to local and federal land managers. Based on these data, we have highlighted three major challenges to the rearing program: 1) high mortality during the subterranean portion of its life cycle (averaging 63% annually) reducing beetle production, 2) asynchrony in estivation emergence relative to the availability of their host HWA minimizing food availability, and 3) unintended field collections of Laricobius spp. larvae on HWA provided to lab-reared larvae complicating rearing procedures. We further highlight corresponding avenues of research aimed at addressing each of these challenges to further improve Laricobius spp. production.

Keywords: insect rearing, biological control, natural enemies, predators

The hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA), Adelges tsugae Annand (Hemiptera: Adelgidae) is a non-native pest to eastern hemlocks, Tsuga canadensis L. (Pinales: Pinaceae), and Carolina hemlocks Tsuga caroliniana Engelmann (Pinales: Pinaceae). HWA was first observed in Richmond, Virginia in 1951 (Gouger 1971, Stoetzel 2002), and was presumably imported previously from Japan on ornamental hemlock nursery stock (Havill et al. 2006, 2016). HWA is native to Mainland China, Japan, Taiwan and western North America (Havill et al. 2006). Adelges spp. have a relatively complicated lifecycle that depends on the availability of a primary and secondary hosts to maintain sexual and asexual reproduction, respectively (Havill and Foottit 2007). Within the introduced range of eastern North America, HWA’s primary host, tiger-tail spruce, Picea torano Voss (Siebold ex K. Koch) (Pinales: Pinaceae), is not present. The absence of tiger-tail spruce and the presence of HWA’s secondary host, hemlock, has resulted in anholocyclic populations of HWA in its adventive range of eastern North America. HWA has two generations per year: 1) sistens and 2) progrediens. The sistens, or overwintering generation, is temporally the longest of the two. Sistens nymphs are present as estivating first instars at the base of hemlock needles throughout summer and following the onset of cooler temperatures, start to develop through three more instars (McClure 1989, Salom et al. 2002, Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2003a). Starting around February, HWA oviposition begins and the eggs of the next generation, the progredientes are laid. The shorter progrediens generation is present from March to late June.

Since its introduction, HWA has spread throughout much of the range of eastern and Carolina hemlocks and is currently established in 22 eastern states in the United States and in Nova Scotia, Canada (Kantola et al. 2019, Virginia Tech 2019). Hemlock mortality caused by HWA feeding can result in whole tree mortality, with larger trees succumbing to infestations more quickly (McClure 1991). Treatment options for managing HWA infestations vary in effectiveness, unwanted secondary environmental effects, and the temporal and spatial scales at which they can be applied (Steward et al. 1998, Silcox 2002, Havill et al. 2016, Mayfield et al. 2020). Of these, the principal tactics readily used are: 1) biological control agents, 2) chemical applications, 3) silvicultural applications, and 4) a combination of tactics through an integrated pest management (IPM) strategy (Mayfield et al. 2020). The emphasis of this manuscript will be on the use of biological control agents.

The Mass Production of Laricobius spp. as Biological Control Agents for HWA

Laricobius spp. have received the most attention as biological control agents for HWA and are known to prey only on Adelgidae (Lawrence and Hlavac 1979, Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2002, Havill and Foottit 2007). They have a univoltine life cycle, in which both the adults and larvae feed on adelgids (Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2002, Vieira et al. 2011, Salom et al. 2012), exhibit significant rates of predation (Jubb et al. 2020), and are associated with their host in both forested and urban environments (Mausel et al. 2010, Toland et al. 2018, Foley et al. 2019, Jubb et al. 2021.

The only Laricobius species endemic to eastern North America is Laricobius rubidus LeConte (Coleoptera: Derodontidae). The primary and preferred host of L. rubidus is the also endemic pine bark adelgid (PBA), Pineus strobi Hartig (Hemiptera: Adelgidae). The host of PBA is eastern white pine, Pinus strobus L. (Pinales: Pinaceae), which often occurs sympatrically with hemlock in both natural and urban landscapes.

Laricobius nigrinus was the first Laricobius species recognized for its potential as a biological control agent following field observations in the coastal rainforests of western North America (Humble 1994, Montgomery and Lyon 1996). They were first collected and imported to a United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) approved Beneficial Insects Containment Facility (BICF) at Virginia Tech in 1997. Following biological evaluation studies (Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2002), L. nigrinus was approved for release in 2000. Over the years, multiple universities and governmental agencies have initiated Laricobius spp. mass rearing programs, with varying degrees of success and production. Currently, Virginia Tech, University of Tennessee, and University of Georgia are the only entities with colonies of Laricobius spp. agents produced for field release. Following the release and establishment of Laricobius nigrinus Fender (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) as a biological control agent in eastern North America, hybridization between the native congener L. rubidus and imported L. nigrinus was observed at a proportion of 11–15% (Havill et al. 2012, Fischer et al. 2015, Mayfield et al. 2015, Wiggins et al. 2016).

In 2006, an additional Laricobius spp., Laricobius osakensis Montgomery and Shiyake (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), was collected in Japan and was also brought to the BICF at Virginia Tech for biological evaluations (Montgomery et al. 2011, Vieira et al. 2011, Story et al. 2012). The goal was to have a complementary agent to L. nigrinus that co-evolved with the pest, HWA, in its native range of Japan (Havill et al. 2006). Following host-range testing and potential impact assessments, L. osakensis was approved for release in 2010 (Fischer et al. 2014, Mooneyham et al. 2016, Toland et al. 2018). However, due to the presence of a cryptic second species within the colony, Laricobius naganoensis Leschen (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), releases were deferred until strict colony purification procedures were implemented (Fischer et al. 2014). Although L. naganoensis was approved for release from quarantine in 2017 (USDA 2017), no releases have occurred and colony purification protocols continue to be used when rearing wild-caught collections of L. osakensis. Rearing requirements for L. osakensis followed the protocol developed for L. nigrinus. It was assumed that the two congeners shared similar thermal and moisture requirements based on climate matching data (Vieira et al. 2013).

With the approval for release of two Laricobius spp. granted, the Insectary at Virginia Tech was the first lab to develop and implement mass rearing protocols (Salom et al. 2012), with the goal of supplying biological control agents to federal and state land managers. In order to produce consistent and reliable specimens for release, specific biological and environmental requirements must be met. This includes mirroring the two distinct life phases (arboreal and subterranean) of Laricobius spp. and adequate provisioning of temperature, light, humidity, and primary and secondary nutrients. Development of the rearing procedures was initially based on the best available knowledge of the biology and environmental conditions of the natural systems. These procedures have evolved over time through scientific testing to optimize production. The long-term nature of this rearing program and the lessons learned have produced a considerable amount data that are analyzed here to better understand our successes and failures. In addition, we aim to highlight potential avenues of research to further increase laboratory production, quality, efficiency, and consistency.

Methods and Materials

Overview of the Past and Present Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for the Mass Production of Laricobius spp. Agents

Laricobius spp. Adult Collections and Importations to Virginia Tech

Inherent in the success of many biological control programs is the ability to mass-produce natural enemies of target insect pests or plant herbivores of weeds within a laboratory insectary. This requires efficient rearing procedures with precise knowledge of a natural enemy’s lifecycle, dietary and thermal requirements, reliable personnel, and quality control (Leppla and Fisher 1989, Cohen and Cheah 2019). Beginning in 1997, the first shipments of L. nigrinus were sent to the Virginia Tech’s BICF in Blacksburg, VA. Here, incipient colonies were established and host-range and developmental biological studies were conducted (Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2002; Salom et al. 2002; Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2003a, 2005). Over the next four years, a colony was maintained in the BICF, however, due to high rates of mortality, further scientific studies were conducted with the goal of increasing colony survivorship in order to have a sufficient number of specimens for research use (Lamb et al. 2005, Salom et al. 2012).

With the approval for release granted and rearing protocols further streamlined, L. nigrinus was removed from quarantine and brought to the Virginia Tech Mass Rearing Insectary in Blacksburg, VA. Mass rearing protocols were put in place in 2004 (Salom et al. 2012). At this time, a field insectary was also established at Kentland Farm, Blacksburg, VA (Mausel et al. 2008, Salom et al. 2011). The long-term goal of our field insectary was to passively produce sufficient field reared specimens without artificially introducing laboratory domestication effects and reducing rearing costs. From 2005 to 2015, in attempts to avoid inbreeding depression through genetic bottlenecking and laboratory domestication, L. nigrinus rearing colonies were restocked annually with wild-caught specimens from either the Puget Sound region in Washington, or from Idaho, USA. It’s been documented that ecotypes of biological agents can vary in weight (Foley et al. 2016), thermal tolerance (Mausel et al. 2011), and morphology (Tipping et al. 2010). Therefore, two ecotypes of L. nigrinus (coastal vs. interior) were collected from climatically distinct areas in the Pacific Northwest with the goal of establishing each ecotype in the eastern United States with respect to their cold tolerant thresholds (Mausel et al. 2011).

Following the original collections in 2006 and the subsequent approval for release of L. osakensis in 2012, there have been four additional overseas collections (2010, 2012, 2015, 2019). Those specimens were sent to Virginia Tech BICF for colony purification, mass rearing, and experimental testing (Fischer et al. 2014).

While, for the most part, the rearing SOP for L. nigrinus outlined by Salom et al. (2012) is still in effect at Virginia Tech, we are now rearing L. osakensis, and there have been incremental changes to the equipment used, changes in the order of operations, the addition of artificial diets for early emerging adults, shifts in temperature requirements, and timing of temperature treatments throughout the rearing season (Salom et al. 2012). For a general diagram on the rearing procedures for Laricobius spp. for each respective life stage see Fig. 1, and for more detailed descriptions of the SOP see Salom et al. (2012).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the specific rearing temperatures, shift in temperature treatments, and arenas used with respect to each distinct life stage (Center: egg, larva, pupa, and adult) for the production Laricobius spp. agents. There are three arenas used (bottom): 1) Larval funnels, 2) Oviposition containers, and 3) Soil estivation containers. The process begins with adult emergence and feeding: A) adults are either field collected or laboratory reared and used as reproductive adults, B) adults are given bouquets of first early instar HWA and an artificial diet. Once oviposition begins: C) Hemlock plant material containing Laricobius spp. eggs embedded in the HWA woolly flocculent are transferred to D) larval funnels. Here larvae develop to the fourth instar prepupa stage and E) drop to the bottom the funnel where they are collected and placed onto the soil in the F) soil estivation arenas. Following pupation and estivation, G) Laricobius spp. adults emerge. A selective cohort is used as P1 reproductive adults for subsequent colony production and the rest are shipped to land mangers throughout the range of HWA infestations.

HWA field collections as host material for Laricobius spp.: In order to supply developing Laricobius spp. colonies with sufficient prey, week-to-bi-weekly collections of HWA infested eastern hemlocks are made from field sites in Virginia and surrounding states between the months of October and June. Hemlock branches infested with HWA are cut, brought back to the mass rearing lab, and are stored in 18.9 liters buckets of H2O. From these branches, individual bouquets of hemlock twigs (20–25 cm long) with high densities of HWA (2–3 per cm) are bundled by securing hemlock twigs in 29.6 ml Waddington North America (WNA) P10 plastic cups filled with Instant Deluxe Floral Foam (Smithers-Oasis North America, Kent, OH) saturated with H2O and wrapped in Parafilm M (Beemis N.A., Neemah, WI). Field collecting HWA as food for the developing colony, without the presence of L. nigrinus and L. rubidus larvae and/or adults on hemlock branches, has been a continuous challenge. This is due to the dispersal of L. nigrinus from original release sites and the presence of L. rubidus on HWA in areas where white pine and hemlock co-occur. Steps are taken to minimize the occurrence of field collected Laricobius larvae and adults as HWA is brought in from the field, details of which are discussed later on.

Oviposition and egg transfer: Laricobius nigrinus start oviposition shortly after HWA sistens adults begin oviposition (Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2003a). Laricobius osakensis start oviposition shortly before HWA sistens adults begins oviposition (Vieira et al. 2013). Laricobius spp. densities in feeding containers are then reduced from 50 to approximately 20–25 adults per container to maximize feeding and oviposition opportunities within the container (Fig. 1). Hemlock/HWA bouquets now containing Laricobius spp. eggs are removed every week from the feeding/oviposition containers and transferred into Berlese larval funnels with additional fresh foliage (Fig. 1). Adult oviposition temperatures during this period are incrementally increased from 4°C in January to a maximum of 10°C in March which coincides with the period of peak Laricobius oviposition.

Larval development and drop: The transferred hemlock bouquets containing Laricobius spp. eggs are held in rearing funnels at 13° ± 2°C (12:12) for the duration of egg and subsequent larval development. When the larvae reach the fourth instar prepupal stage, they drop from the branch into four-ounce Mason jars (Jarden Corporation, Rye, NY) attached to the bottom of the larval funnels. In the early years of rearing Laricobius spp., pupation medium (soil mix) was directly placed at the bottom of the Mason jars three weeks after larval funnel initiation. However, this approach is no longer used (due to the difficulty of separating out the fallen larvae from the soil) and Mason jars are left empty and checked once daily for the presence of prepupae. If premature larvae (not yet prepupae) have fallen into the Mason jars, they are placed back on HWA infested hemlock to continue feeding and developing and are recollected when they drop as mature larvae. Any prepupae located are removed, counted, and placed onto the soil in an estivation container with 5–7 cm of soil media composed of 2:1 peat moss:sand. Prior to adding prepupae, the soil media is saturated with distilled water at ~35% by weight. The weight of each soil container is then maintained throughout the season. Once in the estivation container, prepupae burrow into the soil and begin pupation. They are kept in estivation containers at a density of approximately 200 individuals per 820 cm3 of soil (Fig. 1).

Pupation and estivation: Pupating Laricobius spp. are held in soil estivation containers at 13 ± 2°C (12:12) for approximately 6–7 wk until pupation is complete. Temperatures are then adjusted to 19°C for adult summer estivation.

Adult emergence and feeding: As HWA breaks its summer dormancy and develops through its four nymphal stages, Laricobius adults emerge from the soil and begin predation. It is precisely at this time, when HWA is breaking dormancy, when the temperature is deceased from 19° to 13°C in the insectary to simulate seasonal changes in temperature. This temperature decrease prompts Laricobius spp. to emerge from the soil (Lamb et al. 2007, Salom et al. 2012). From 2004 to 2007, following Laricobius spp. adult emergence prior to estivation break of HWA, beetles were given bouquets of hemlocks infested with first instar estivating HWA nymphs as a nutrient source (Fig. 1). From 2008 until present, the early emerging adults have been offered an artificial diet; Lacewing and Ladybug Food (Wheast, Planet Naturals, Bozeman, MT) or the CC diet (egg-based), in addition to bouquets of hemlocks containing estivating first instar HWA nymphs (Cohen and Cheah 2015). A quarter-sized spread of artificial diet is offered on filter paper, which is taped to the side of each feeding/oviposition container. The diet is replaced every 2 wk until HWA reaches the second instar stage. The early emerging adults are held at temperatures of 4°C, 12:12 L:D, and at densities of approximately 50 adults per container (Fig. 1). Host material and artificial diets are replaced every 2 wk. Following emergence, adults are identified to species based on their morphology (coloration, size, and presence, absence, and shape of their pronotal tooth) using a dissection microscope (Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2006, Leschen 2011).

Data Analysis

Rearing data were collected over 15 yr; from 2004 to 2019. Statistical analysis of the data was conducted using R version 3.6.1 and JMP version 15 and a P ≤ 0.05 was considered significant for all of the following analyses. Data such as larval drop Julian date (JD), adult emergence JD, and subterranean survivorship are reported for each container (Tables 1–3). Calendar dates reported for corresponding JD are for nonleap years. The larval drop date for each container is the last JD that larvae were placed in the container (before reaching capacity), and the container’s adult emergence date is the first day that adults emerged from that container (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Summary of the total number of Laricobius spp. reproductive adults and larvae produced by Julian date at the Virginia Tech insectary and Pearson’s correlation for each year and species relating survivorship of emerging adults to date they first went into the soil

| Julian date of larvae drop | Survivorship vs. first day underground (Pearson’s correlation) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Spp. | Fecund adults | Total larvae | Minimum | 25% | 50% | 75% | Maximum | Mean no. ± SD | Soil containers (n) | Coefficient (r) | P-value |

| 2004 | LN | NA | 24,803 | 20 | 62 | 93 | 112 | 159 | 88 ± 29.3 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2005 | LN | 713 | 19,285 | 95 | 123 | 133 | 152 | 192 | 137 ± 17.7 | 16 | −0.18 | 0.483 |

| 2006 | LN | 1,067 | 13,205 | 102 | 126 | 144 | 156 | 214 | 143 ± 22.0 | 34 | −0.13 | 0.47 |

| 2007 | LN | 1,231 | 40,912 | 72 | 121 | 133 | 145 | 190 | 133 ± 17.2 | 199 | −0.41 | <0.001* |

| 2008 | LN | 1,200 | 45,985 | 72 | 128 | 139 | 158 | 198 | 140 ± 23.1 | 237 | −0.47 | <0.001* |

| 2009 | LN | 1,230 | 32,009 | 86 | 123 | 135 | 145 | 202 | 135 ± 18.7 | 160 | −0.76 | <0.001* |

| 2010 | LN | 1,070 | 38,352 | 76 | 114 | 127 | 138 | 196 | 126 ± 19.7 | 191 | −0.55 | <0.001* |

| 2011 | LN | 300 | 8,039 | 93 | 117 | 132 | 149 | 199 | 134 ± 21.9 | 40 | −0.81 | <0.001* |

| LO | 1200 | 27,987 | 79 | 114 | 124 | 137 | 183 | 127 ± 18.4 | 40 | −0.47 | 0.002* | |

| 2012 | LN | 245 | 2,823 | 72 | 109 | 125 | 144 | 191 | 129 ± 28.2 | 16 | 0.01 | 0.968 |

| LO | 800 | 10,691 | 60 | 89 | 110 | 125 | 180 | 109 ± 26.6 | 86 | 0.03 | 0.752 | |

| 2013 | LN | 470 | 11,561 | 84 | 109 | 123 | 139 | 171 | 124 ± 18.5 | 72 | −0.31 | 0.008* |

| LO | 440 | 32,389 | 54 | 92 | 108 | 128 | 184 | 110 ± 24.4 | 176 | −0.02 | 0.749 | |

| 2014 | LN | 336 | 5,803 | 65 | 114 | 130 | 146 | 182 | 130 ± 21.2 | 31 | −0.21 | 0.268 |

| LO | 735 | 29,812 | 61 | 119 | 135 | 152 | 184 | 135 ± 23.0 | 162 | −0.47 | <0.001* | |

| 2015 | LN | 387 | 7,622 | 61 | 103 | 118 | 132 | 176 | 117 ± 21.3 | 43 | −0.50 | <0.001* |

| LO | 342 | 11,944 | 61 | 92 | 105 | 120 | 176 | 107 ± 21.8 | 76 | −0.53 | <0.001* | |

| 2016 | LN | 42 | 1,556 | 66 | 103 | 118 | 134 | 182 | 119 ± 23.4 | 14 | −0.37 | 0.197 |

| LO | 500 | 21,420 | 54 | 78 | 94 | 114 | 180 | 99 ± 22.1 | 204 | −0.27 | <0.001* | |

| 2017 | LN | 277 | 11,805 | 57 | 97 | 115 | 129 | 195 | 114 ± 26.8 | 63 | −0.17 | 0.178 |

| LO | 600 | 18,612 | 58 | 91 | 113 | 127 | 188 | 111 ± 25.8 | 145 | −0.41 | <0.001* | |

| 2018 | LO | 365 | 42,753 | 65 | 105 | 114 | 126 | 189 | 117 ± 18.6 | 201 | 0.05 | 0.453 |

| 2019 | LN | NA | 792 | 115 | 135 | 150 | 165 | 198 | 152 ± 20.8 | 4 | 0.83 | 0.17 |

| LO | 578 | 14,535 | 99 | 123 | 138 | 159 | 213 | 142 ± 21.8 | 71 | 0.64 | <0.001* | |

| 2004–2019 | LN | 8,594 | 264,552 | 76 | 112 | 128 | 143 | 190 | 128 ± 22.0 | 1120 | −0.50a | <0.001* a |

| 2011–2019 | LO | 5,560 | 210,143 | 66 | 100 | 116 | 132 | 186 | 117 ± 23.1 | 1161 | −0.18a | <0.001* a |

| 2004–2019 | LN+LO | 14,154 | 474,695 | 72 | 108 | 123 | 139 | 188 | 124 ± 22.4 | – | – | – |

LN = Laricobius nigrinus.

LO = Laricobius osakensis.

*Statistically significant P-value (<0.05).

n = total number of soil containers.

aCalculated using Fisher’s z′ transformation.

– Analyses were not conducted.

Table 2.

Summary of the total number of Laricobius spp. adults produced at the Virginia Tech insectary for each year and Julian data quantiles of emergence with the mean ± SD

| Year | Species | Total | Soil containers | Julian date of adult emergence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| adults | (n) | First | 25% | 50% | 75% | Last | Mean ± SD | ||

| 2004 | LN | 7,828 | NA | 233 | 293 | 300 | 307 | 326 | 300 ± 13.2 |

| 2005 | LN | 3,416 | 16 | 262 | 293 | 301 | 308 | 341 | 301 ± 10.8 |

| 2006 | LN | 1,995 | 34 | 264 | 293 | 300 | 308 | 365 | 300 ± 21.0 |

| 2007 | LN | 15,136 | 199 | 199 | 291 | 305 | 314 | 355 | 301 ± 18.1 |

| 2008 | LN | 20,526 | 237 | 211 | 261 | 276 | 302 | 339 | 280 ± 25.6 |

| 2009 | LN | 13,060 | 160 | 238 | 301 | 308 | 315 | 348 | 307 ± 12.5 |

| 2010 | LN | 26,774 | 191 | 204 | 299 | 308 | 315 | 363 | 304 ± 18.9 |

| 2011 | LN | 3,757 | 40 | 231 | 305 | 311 | 318 | 340 | 311 ± 11.3 |

| LO | 5,896 | 40 | 265 | 302 | 309 | 317 | 341 | 309 ± 12.1 | |

| LN+LO | 9,653 | 80 | 231 | 303 | 310 | 317 | 341 | 310 ± 11.8 | |

| 2012 | LN | 1,248 | 16 | 256 | 295 | 308 | 318 | 351 | 306 ± 16.5 |

| LO | 2,391 | 86 | 163 | 294 | 303 | 310 | 351 | 300 ± 23.0 | |

| LN+LO | 3,639 | 102 | 163 | 294 | 304 | 314 | 351 | 302 ± 21.2 | |

| 2013 | LN | 5,918 | 72 | 163 | 287 | 304 | 314 | 356 | 300 ± 18.9 |

| LO | 13,896 | 176 | 158 | 283 | 300 | 313 | 364 | 298 ± 23.1 | |

| LN+LO | 19,814 | 248 | 158 | 284 | 302 | 313 | 364 | 298 ± 21.9 | |

| 2014 | LN | 2,862 | 31 | 166 | 301 | 311 | 317 | 349 | 307 ± 16.0 |

| LO | 8,680 | 162 | 164 | 272 | 292 | 304 | 348 | 288 ± 21.0 | |

| LN+LO | 11,542 | 193 | 164 | 277 | 297 | 310 | 349 | 293 ± 21.5 | |

| 2015 | LN | 1,750 | 43 | 182 | 246 | 256 | 274 | 331 | 260 ± 25.3 |

| LO | 6,876 | 76 | 163 | 302 | 313 | 321 | 364 | 311 ± 16.7 | |

| LN+LO | 8,626 | 119 | 163 | 289 | 308 | 319 | 364 | 301 ± 27.6 | |

| 2016 | LN | 870 | 14 | 258 | 307 | 318 | 327 | 364 | 316 ± 22.1 |

| LO | 8,385 | 204 | 182 | 263 | 281 | 302 | 364 | 281 ± 27.4 | |

| LN+LO | 9,255 | 218 | 182 | 265 | 286 | 306 | 364 | 284 ± 28.8 | |

| 2017 | LN | 3,543 | 63 | 205 | 263 | 283 | 296 | 315 | 278 ± 23.5 |

| LO | 5,029 | 145 | 205 | 275 | 291 | 302 | 316 | 288 ± 18.0 | |

| LN+LO | 8,572 | 208 | 205 | 271 | 287 | 300 | 316 | 284 ± 21.0 | |

| 2018 | LO | 15,322 | 201 | 222 | 274 | 304 | 317 | 361 | 296 ± 27.9 |

| 2019 | LN | 309 | 4 | 226 | 254 | 277 | 290 | 328 | 273 ± 22.1 |

| LO | 4,375 | 71 | 226 | 294 | 304 | 311 | 349 | 300 ± 17.8 | |

| LN+LO | 4,684 | 75 | 226 | 291 | 303 | 311 | 349 | 298 ± 19.3 | |

| 2004–2019 | LN | 108,992 | 1120 | 163 | 286 | 298 | 308 | 345 | 296 ± 18.4 |

| 2011–2019 | LO | 70,850 | 1161 | 158 | 284 | 300 | 311 | 351 | 297 ± 20.8 |

| 2004–2019 | LN+LO | 179,842 | 2281 | 158 | 285 | 298 | 309 | 347 | 297 ± 19.3 |

LN = Laricobius nigrinus.

LO = Laricobius osakensis.

n = total number of soil container.

The first day larvae went underground and the number of days larvae spent underground were correlated against percent subterranean survivorship using the Pearson’s correlation test for L. nigrinus, L. osakensis, and both L. nigrinus and L. osakensis combined from 2005 to 2019 (Tables 1 and 3). Averages of each Pearson’s correlations were calculated using a Fisher’s r-to-Z transformation (Tables 1 and 3).

Table 3.

Summary of Laricobius spp. adult subterranean survivorship at the Virginia Tech insectary for each year and species and Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Survivorship vs. Median Days Underground). Correlation coefficients averages from 2005 to 2019 are weighted by the number of data points used to calculate each year’s correlation

| Survivorship vs. median days underground | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Species | Subterranean | Median days | (Pearson’s correlation) | ||

| survivorship (%) | Underground1 | Soil containers (n) | Coefficient (r) | P-value | ||

| 2004 | LN | 31.6 | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| 2005 | LN | 17.7 | 197 | 16 | 0.51 | 0.043* |

| 2006 | LN | 15.1 | 184 | 34 | 0.44 | 0.009* |

| 2007 | LN | 37.0 | 193 | 199 | 0.54 | <0.001* |

| 2008 | LN | 44.6 | 178 | 237 | 0.46 | <0.001* |

| 2009 | LN | 40.8 | 191 | 160 | 0.84 | <0.001* |

| 2010 | LN | 69.8 | 199 | 191 | 0.63 | <0.001* |

| 2011 | LN | 46.7 | 196 | 40 | 0.81 | <0.001* |

| LO | 21.1 | 219 | 40 | 0.63 | <0.001* | |

| 2012 | LN | 44.2 | 211 | 16 | 0.02 | 0.951 |

| LO | 22.4 | 227 | 86 | −0.04 | 0.720 | |

| 2013 | LN | 51.2 | 207 | 72 | 0.36 | <0.001* |

| LO | 42.9 | 221 | 176 | 0.31 | <0.001* | |

| 2014 | LN | 49.3 | 213 | 31 | 0.25 | 0.179 |

| LO | 29.1 | 187 | 162 | 0.59 | <0.001* | |

| 2015 | LN | 23.0 | 202 | 43 | 0.51 | <0.001* |

| LO | 57.6 | 250 | 76 | 0.50 | <0.001* | |

| 2016 | LN | 55.9 | 237 | 14 | 0.28 | 0.341 |

| LO | 39.1 | 227 | 204 | 0.45 | <0.001* | |

| 2017 | LN | 30.0 | 195 | 63 | 0.36 | 0.004* |

| LO | 27.0 | 205 | 145 | 0.50 | <0.001* | |

| 2018 | LO | 35.8 | 216 | 201 | 0.37 | <0.001* |

| 2019 | LN | 39.0 | 165 | 4 | −0.86 | 0.136 |

| LO | 30.1 | 178 | 71 | −0.53 | <0.001* | |

| 2004–2019 | LN | 39.7 | 198 | 1120 | 0.58a | <0.001* a |

| 2011–2019 | LO | 33.9 | 214 | 1161 | 0.37a | <0.001* a |

LN = Laricobius nigrinus.

LO = Laricobius osakensis.

n = Total number of soil containers.

1 = Julian date.

*Statistically significant P-value (<0.05).

aCalculated using Fisher’s z′ transformation.

The larval drop JD, adult emergence JD, and the total days underground data did not follow normal distributions, resulting in the use of the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis and Friedman tests. Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to determine whether there was a difference in the median larval drop JD, adult emergence JD, and total days underground across years. A Friedman test, using year as the blocking variable, was used to determine whether there was a difference in the median larval drop JD, adult emergence JD, and total days underground, between the two species. Due to the unequal number of observations across the different species/years, an approximate Friedman test with repeated measures was performed in JMP by conducting a Wilcoxon rank-sum test on the ranks of the response blocked by year.

Results

Laricobius nigrinus and L. osakensis have been mass-produced by Virginia Tech since 2004 and 2010, respectively. To date, Virginia Tech has produced 264,552 larvae and 108,992 adults of L. nigrinus and 210,143 larvae and 70,850 adults of L. osakensis (Tables 1 and 2). Following emergence and prior to release or experimentation, 70,307 (39%) additional L. nigrinus and L. osakensis adult deaths occurred across all years. The total number of L. nigrinus reproductive adults (P1) used for colony foundation from 2005 to 2019 was 8,594 and ranged from 26 in 2019 to 713 in 2005 (Table 1). The total number of L. osakensis reproductive adults (P1) used for colony foundation from 2011 to 2019 was 5,560 and ranged from 342 in 2015 to 1,200 in 2011 (Table 1).

Larval Drop

The average total number of days L. nigrinus larvae dropped from 2004 to 2019 was 114, and ranged from JD 76 (March 17) to 190 (July 9) with a median of 128 (May 8) (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The average total number of days L. osakensis larvae dropped from 2010 to 2019 was 120 and ranged from JD 66 (March 7) to 186 (July 8) with a median of 116 (May 26).

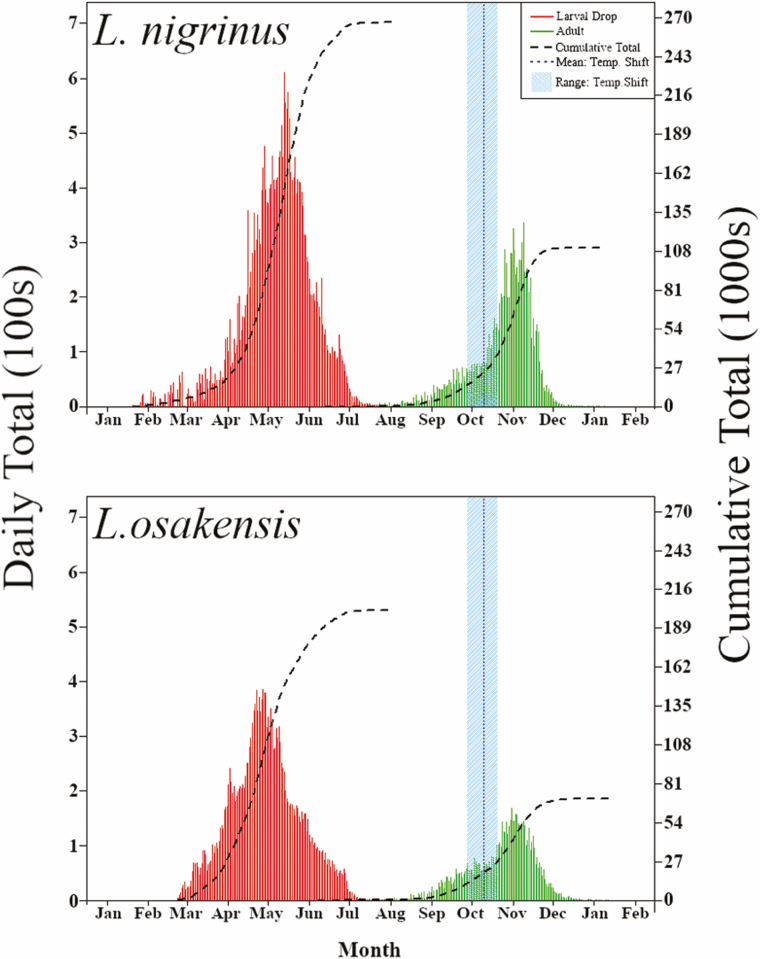

Fig. 2.

Daily and cumulative larval drop (red) and subsequent adults emerged (green) from 2014 to 2019 for L. nigrinus (top) and L. osakensis (bottom). The blue dotted line (mean) and the surrounding light blue band shows the range in which the temperatures were changed from 19 to 13°C to stimulate emergences based on the field observation of estivation break of HWA.

Due to year-to-year variability in the timing of temperature treatments, the unitization of wild-caught and laboratory reared P1 reproductive adults, and host availability and quality, we expected to find differences in the responses of interest (median larval drop JD) across the years and between the two species. Kruskal–Wallis analysis on JD larvae drop, from 2005 to 2019, showed a significant difference across the years for L. nigrinus (X2 = 131.76, d.f. = 13, P < 0.001) and for L. osakensis (X2 = 236.34, d.f. = 8, P < 0.001) from 2011 to 2019.

When it came to comparing the two species across years, only data from 2011 to 2017 and 2019 were included due to not having data for both species in other years. Friedman’s pairwise comparison test showed a significant difference between both species (X2 = 11.56, d.f. = 1, P = 0.007). The result of this test supports the observation that the median larval drop date is later for L. nigrinus (JD 128) than for L. osakensis (JD 116) across the years.

The first day underground (i.e., last larvae drop date for each container) for L. nigrinus and L. osakensis was significantly negatively correlated with the percent survivorship from 2007–2011, 2013 and 2015 and from 2011, 2014–2017, respectively (Table 1). From 2004 to 2019, the average Pearson’s correlation coefficient and corresponding P-value for L. nigrinus was −0.50 and <0.001, respectively (Table 1). From 2010 to 2019, the average Pearson’s correlation coefficient and corresponding P-value for L. osakensis was −0.18 and <0.001, respectively (Table 1). The average correlation coefficient of survivorship versus first day underground for L. nigrinus is 64% larger than for L. osakensis (Table 3). These results suggest, especially for L. nigrinus, that the earlier each larvae cohort drop to the soil the higher their survivorship.

Subterranean Duration and Survivorship

The average median number of days spent underground for L. nigrinus was 198 and for L. osakensis was 214, and ranged from 165 to 237 and 178 to 250, respectively (Table 3). The average subterranean survivorship, which includes both pupation and adult estivation, for L. nigrinus and L. osakensis was 39.7 and 33.9%, respectively.

Kruskal–Wallis analysis on number of days underground, from 2005 to 2019, showed a significant difference between each year for L. nigrinus (X2 = 229.38, d.f. = 13, P < 0.001) and from 2011 to 2019 for L. osakensis (X2 = 403.14, d.f. = 8, P < 0.001). Friedman’s pairwise comparison test showed a significant difference between L. nigrinus and L. osakensis (X2 = 27.54, d.f. = 1, P < 0.001). This test result supports the observation that the median number of days spent underground across the years is higher for L. osakensis compared to L. nigrinus.

The median days spent underground was significantly positively correlated with subterranean survivorship for a majority (71%) of the rearing years for L. nigrinus (from 2005 to 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017 (Table 3). From 2005 to 2019, the average Pearson’s correlation coefficient and corresponding P-value for L. nigrinus was 0.58 and <0.001, respectively (Table 3). The median days spent underground was significantly positively correlated with subterranean survivorship for a majority (70%) of the rearing years for L. osakensis (from 2011, 2013 to 2018 (Table 3). From 2011 to 2019, the average Pearson’s correlation coefficient and corresponding P-value for L. nigrinus was 0.37 and <0.001, respectively (Table 3). The average correlation coefficient of survivorship versus median days underground for L. nigrinus is 36% larger than for L. osakensis (Table 3). These results suggest that the longer Laricobius spp. are underground the higher their survivorship.

Adult Emergence

The JD window of emergence for L. nigrinus ranged from 153 (June 2) to 345 (December 11) and for L. osakensis was 158 (June 7) to 351 (December 17). The average median adult emergence JD for L. nigrinus ranged from 256 (September 13) to 318 (November 14) (Δ = 62 d) with mean and standard deviation of 296 (October 23) ± 18.4 from 2004 to 2019 (Table 2). The average median adult emergence JD for L. osakensis ranged 281 (October 8) to 313 (November 9) (Δ = 32 d) with mean and standard deviation of 297 (October 24) ± 20.8 from 2011 to 2019 (Table 2).

Kruskal–Wallis analysis on median emergence JD, from 2005 to 2019, showed a significant difference across each year for L. nigrinus (X2 = 394.33, d.f. = 13, P < 0.001) and from 2011 to 2019 for L. osakensis (X2 = 379.12, d.f. = 8, P < 0.001). Friedman’s pairwise comparison test showed a significant difference between both species’ median adult emergence JD (X2 = 6.85, d.f. = 1, P = 0.009).

Discussion

When the mass production of Laricobius agents began, the goals were to supply local, state, and federal land managers with biological control agents for release, and to have enough live insects to conduct related experiments regarding the biological control of HWA. The tandem pursuit of these two goals has allowed us to continue the mass production of Laricobius spp. agents over the past decade and a half at Virginia Tech. From inception of our rearing program in 2004 until present, we have sent an average, 693 Laricobius spp. per shipment to 43 collaborators across 15 states (Table 4). The states that received Laricobius spp. are GA, KY, MA, MD, ME, NC, NH, NJ, NY, OH, PA, RI, VA, VT, and WV. These collaborators have played a pivotal role in dispersing these agents across the eastern and Carolina hemlock landscape in eastern North America with 13 of the 15 states who’ve received beetles having confirmed establishment (Virginia Tech 2019).

Table 4.

Number of Laricobius spp. shipments from the Virginia Tech insectary and the number beetles released per State and overall from 2004 to 2019

| Release State | Total no. of | Total no. released |

|---|---|---|

| shipments | ||

| GA | 1 | 600 |

| KY | 4 | 6,500 |

| MA | 7 | 5,200 |

| MD | 18 | 13,850 |

| ME | 12 | 6,510 |

| NC | 1 | 200 |

| NH | 14 | 6,650 |

| NJ | 7 | 5,800 |

| NY | 7 | 4,010 |

| OH | 10 | 4,950 |

| PA | 30 | 17,810 |

| RI | 1 | 300 |

| VA | 20 | 16,755 |

| VT | 2 | 1,000 |

| WV | 24 | 19,400 |

| Total | 158 | 109,535 |

Over the past decade and half of rearing Laricobius spp. at Virginia Tech, the observation of ‘premature’ larvae found in the Mason jars attached to the bottom of the funnels has consistently been noted. Salom et al. (2012), described these premature larvae as smaller, darker in color, and less mobile than mature larvae. It is unclear why these larvae premature drop from the infested plant material. The premature larvae are typically found throughout the larval rearing season and are placed back onto the hemlock foliage containing HWA, whereby they presumably resume predation and larval development before dropping back down into the funnels. Following the observation of larvae in the funnels, a technician visually determines based on size, color, and mobility if the specimens are premature or not. However, the weight difference between second and third instars to the fourth prepupal instar is on the scale of milligrams and not always easily discernable by the naked eye. It is possible these larvae are being placed onto the soil and do not have enough resource, measured by biomass, to make it thorough pupation and/or remain in estivation.

While there is variability in the starting number of adults for each species and from year-to-year, based on our experience, the ideal starting number of reproductive adults range is between 800 and 1000 P1 at a sex ratio of roughly 1:1. This rearing capacity is limited by the physical space available in the rearing facility as well as available personnel. The lower end of the range is more suitable for colony purification of L. osakensis, as physical space requirements increase with the need to keep individual groups separated (Fischer et al. 2014). The higher end of the range is more appropriate for L. nigrinus, which are reared using standard protocols.

The average median JD on which 50% of the larval population dropped and were placed onto soil is later for L. nigrinus compared to L. osakensis. A possible explanation for these results is the timing of when oviposition starts for the respective species. Laricobius osakensis have been observed starting oviposition as early as mid-December (Vieira et al. 2013, Personal obs.) in its native range of Japan, in the laboratory, and at release sites, whereas oviposition for L. nigrinus has been observed as early as late January (Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2003b). The phenological rate of development for L. osakensis is not fully understood within its introduced range of eastern North America and warrants further investigation.

Based on our analysis of these data, we have highlighted three major challenges in Laricobius spp. mass production and corresponding potential avenues of research. These need to be adequately addressed and understood in order to further increase laboratory quality, consistency, and production of Laricobius agents. The first major challenge is higher than desired colony mortality during pupation and estivation, when the insects are in their subterranean environment (Table 3). A second major challenge has been the early emergence of Laricobius spp. relative to their host, HWA (Table 2 and Fig. 2). The final challenge involves the presence of field-collected larvae and adults on HWA infested branches used to feed lab-reared colonies. Because L. nigrinus has established at and dispersed from many original release sites, finding locations where L. nigrinus is not present is a continuous issue that complicates our rearing efforts.

Challenge 1: Subterranean Duration and Survivorship

During the subterranean portion of the Laricobius spp. lifecycle (~6 mo), the insect pupates and enters into a period of presumed estivation. From 2004 until 2019, the average subterranean colony mortality for L. nigrinus and L. osakensis was 40 and 34%, respectively (Table 3). The reason for such severe mortality is unclear. Some variables we might consider are soil moisture and larval density per soil container. Lamb et al. (2007) reported a decrease in adult emergence at soil moisture levels outside of the 40–50% range. However, our moisture levels are consistently monitored and maintained at or close to recommended levels and does not explain our results. Salom et al. (2012) did not see a density effect on survivorship when evaluating 120, 240, and 360 larvae per container. As we have maintained our larval densities at ~200 per soil container, it is unlikely larval densities explain our mortality rates.

Laricobius spp. subterranean mortality in a field setting is not currently well understood. Jones et al. (2014) experimentally tested the subterranean survivorship of L. nigrinus in northern Georgia, USA, which corresponds to the southern limit of eastern hemlock, and recovered four adults from the estimated 1,440 larvae released. Jones et al. (2014) contributed their findings and lack of recoveries to the thermal developmental limit of 21°C for L. nigrinus (Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2003b). Additional studies need to be conducted to accurately document the subterranean survivorship of L. nigrinus and L. osakensis across their established range in relation to site factors and thermal requirements.

Avenues of research that could serve to increase colony production and subterranean survivorship is to determine the life stage (pupation or estivation) most susceptible to mortality, the effect of fourth instar larvae biomass on Laricobius spp. subterranean duration and survivorship, the effect of prepupa handling time on subterranean survivorship, and the nutrient quality of HWA in relation to tree age, health, and stage of infestation.

Challenge 2: Timing of Emergence

The median emergence time for L. nigrinus was significantly different from that of L. osakensis. Moreover, the average median range (the number of days during which 50% of the population emerges) for L. osakensis (32 d) is almost half compared to that of L. nigrinus (64 d). Based on these data, L. osakensis also remains in the soil longer than L. nigrinus.

When Laricobius spp. adults emerge before HWA breaks estivation, additional colony mortality occurs. Early emergence has been and continues to be an issue and suggests there are underlying biological variations that are not fully understood (Fig. 1). The total number of adults for both species that emerged early from estivation from 2004 to 2019 was 179,842. Of those, 39% (70,307) died prior to field release or experimental research. To decrease further colony mortality following early emergence, the use of interim diets and slight changes to temperature treatment and timing of temperature treatments have been implemented or recently suggested.

Interim diets used by Virginia Tech have two main forms: 1) various artificial yeast, egg, and protein mixtures, and 2) adelgid eggs of either HWA from the previous generation kept at their minimal developmental threshold of 5°C (Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2003b), to slow development, or from secondary adelgid host such as PBA. The artificial diet currently used is ‘Lacewing and Ladybug Food’. Cohen and Cheah (2015) concluded the diet as ‘highly effective in extending the survival of adults’. In attempts to decrease any further mortality of Laricobius spp. adults, HWA sistens and PBA eggs are supplied. Although, Laricobius spp. cannot complete development on PBA eggs solely (Zilahi-Balogh et al. 2002, Vieira et al. 2011), feeding still occurs. There are no data available on the effects that consumption of older stored HWA progrediens or freshly collected PBA eggs have on increasing Laricobius spp. survivorship. However, based on anecdotal observation, we believe there is a net positive effect.

From 2004 until 2019, the average median number of days spent underground for L. nigrinus and L. osakensis was 198 and 214, respectively (Table 3). Salom et al (2012) determined that both moisture and temperature influence the number of days spent underground. The decision for when to shift from simulated summer temperatures (19°C) to simulated fall temperatures (13°C) is based on field observations of HWA breaking estivation in southwest Virginia. This reduction in laboratory temperature is usually initiated in early to mid-October around JD 274 (Fig. 2). Following this shift in temperature at the insectary, the median JD at which 50% of the adults emerged for L. nigrinus and L. osakensis was 298 and 300, respectively (Table 2). Therefore, while there is substantial variability in the timing of initial emergence, half of the colony consistently emerges from the subterranean environment following the shift to cooler temperatures (Table 2 and Fig. 2).

Based on these data, a potential technique that could be used to subvert the phenomenon of early emergence and to increase subterranean survivorship of Laricobius spp. is to allow the beetles to have a longer subterranean period with respect to how long each larval cohort is in the soil. For example, the Pearson’s correlation between days spent underground and survivorship shows a significant positive relationship, for most years (Table 3). These results suggest that the longer the beetles are in the soil the greater their survivorship, on a per soil container basis. In addition, the Pearson’s correlation between first day underground and survivorship shows a significant negative relationship, for most years (Table 1). These results suggest that the first cohort of larvae to make it to the soil, and thereby having a longer subterranean period, also has a higher survivorship.

Together, these results indicate the potential to increase subterranean survivorship. Instead of making the temperature shift on the same date for all soil containers (based on field-observed estivation break), the temperature-shift date could be varied by container, based on the number of days each cohort have been in the soil. This ensures a more uniform subterranean period (of adequate length) for each estivation container.

Challenge 3: Unintended Field Collections of Laricobius spp. Larvae

Laricobius nigrinus was first released from 2003 to 2005, in 22 localities from Georgia to Massachusetts (Mausel et al. 2010). Following a three-year sampling period, establishment was confirmed at 13 locations in plant hardiness zones 6a, 6b, and 5b (Mausel et al. 2010). Since 2005, L. nigrinus releases have continued and this species is now established >13 states in both forest and urban environments (Foley et al. 2019, Virginia Tech 2019, Jubb et al. 2021). The dispersal and subsequent establishment of L. nigrinus from field release sites is likely larger than previously reported (Davis et al. 2012, Foley et al. 2019). During weekly to bi-weekly food collections, it is challenging to find locations in southwest Virginia and the surrounding area where Laricobius spp. are not present. Unintended field collections of Laricobius spp., whether L. nigrinus, L. rubidus, or hybrids thereof, further complicate rearing procedures by reducing the food availability for the lab reared colony, by disrupting the synchrony of larval developmental progression, and increasing the handling time for technicians when identifying species morphologically following emergence.

Laricobius nigrinus has overwhelmingly been considered the focal predator of HWA sistens by numerous governmental agencies, universities, and private stakeholders, each with the goal of releasing as many agents as possible. This was either done through the mass production of these agents (Salom et al. 2012), or through the relocation of these agents directly from the PNW (McDonald et al. 2011). As a result, L. nigrinus is now widespread across most of the HWA infested eastern hemlock and Carolina hemlock range (Foley et al. 2019, Virginia Tech 2019, Jubb et al. 2021). This same initiative has not been as exhaustive for L. osakensis as it has been for L. nigrinus. Therefore, we foresee the rate of establishment of L. osakensis across the eastern and Carolina hemlock range occurring at a slower pace.

Following HWA field collections, where the presence of Laricobius spp. is noted, efforts are made to avoid those collection areas in the future. In attempts to capitalize on regular cycles of quick population growth and decline of HWA, we also try to find new source populations of HWA, hoping that Laricobius spp. are not yet established there. From a mass rearing perspective, we foresee the unwanted field collection of unidentified species of Laricobius larvae as a continuing disruption within the rearing process, and therefore, we must adapt accordingly. As food is brought in from the field to the Insectary and stored in 18.9 liters buckets, prior to bouquet construction, subsamples are scouted for the presence of Laricobius spp. eggs and larvae. In addition, when scouting is neither effective nor sufficiently comprehensive, phenological anomalies can aid detection of field-collected insects. The date at which larvae start appearing at the bottom of the funnels, in relation to the entire colony’s phenology, is particularly informative. For example, if fourth instar prepupal larvae are found in mason jars when the majority of the lab colony larvae are still developmentally younger (i.e., second instar), they are considered field-caught larvae.

Laricobius nigrinus is an important species in the biological control effort against HWA. However, limited laboratory resources and the widespread release and subsequent establishment of L. nigrinus across the landscape raises an earnest question: is there a need for continued mass production of this species? It is precisely with this question in mind that Virginia Tech discontinued the mass production of L. nigrinus in 2018 and focused on a species that is not already widely established, L. osakensis. However, in subsequent years, field-caught fourth instar prepupal Laricobius spp. larvae continued to be found in Mason jars, and therefore soil estivation arenas were prepared so that those individuals could be reared to the adult stage and later released. Moving forward, mass production at Virginia Tech will continue to be focused on L. osakensis, however, retaining, rearing, and releasing field caught L. nigrinus is a worthwhile side effort.

From an applied perspective, the ubiquity of L. nigrinus throughout its introduced landscape of eastern North America is promising. An operational metric often used to help define a successful biological control agent is its establishment and subsequent dispersal success and capabilities (Messenger et al. 1976, Goode et al. 2019). Evidence suggests that L. nigrinus is established at most release sites, is dispersing from those sites into new environments that contain hemlocks infested with HWA, and is exhibiting significant predation of HWA (Mausel et al. 2008, Mayfield et al. 2015, Jubb et al. 2020). However, Laricobius spp. by themselves are not sufficient in reducing HWA populations to acceptable levels and are but one tool in the overarching IPM strategy for HWA (Mayfield et al. 2020).

Lastly, it is with the undesirable field-caught L. nigrinus and/or L. rubidus in mind, that these data must be examined carefully. During larval production, species identity and the number of undesirable field-caught specimens brought into the lab are difficult to discern. Laricobius larval species determination, based on morphology, is not possible. However, when L. nigrinus and L. osakensis become adults, morphology can be used to separate these species. The aforementioned steps of scouting host material as it’s brought into the lab and observing phenologically asynchronous prepupal larval drops are taken to help identify the presence of undesirable field-caught Laricobius spp., but does not completely stop the input of field-caught insects into the insectary.

Overall, the production of Laricobius spp. at Virginia Tech has been a successful endeavor that has not only served our local forest and urban ecosystems, but also those numerous collaborators in multiple states who have received shipments of predatory beetles. Based on these analyses and results of rearing Laricobius spp. over the past 15 yr, we recommend several areas of research in order to understand their biological requirements and to increase laboratory production. These include: 1) constant temperature experiments of L. osakensis to determine the developmental rate and ideal temperatures for rearing with respect to each life stage and phase, 2) evaluate the effect of Laricobius spp. larval biomass on their subterranean survivorship and timing of emergence, 3) study Laricobius spp. subterranean survivorship in a field setting as it relates to site factors, 4) assess the effect of handling time for prepupae, 5) determine the nutrient quality of HWA in relation to tree health, age, and stage of infestation, and 6) stagger the changes in temperature with respect to how long each larval cohort is in the soil.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Ryan Mays for his dedication in supplying Laricobius spp. colonies with fresh host material and all the technicians, laboratory assistants, and graduate students who have played a major role in the production of Laricobius spp. agents for field release and experimentation. We would also like to thank Shiyake Shigehiko with the Natural History Museum in Osaka, Japan as our overseas collaborator and all the State and Federal collaborators who have received and released Laricobius agents of the over the past decade and half. We would also like to thank Dr. Albert Mayfield for his review and suggestions prior to submission. This research was supported by the USDA-Forest Service Cooperative agreement 16-CA-1142004-086 and USDA APHIS PPQ grant AP19PPQFO000C566.

Author Contributions

JRF: Investigation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Visualization; Conceptualization; Supervision; Funding acquisition; Methodology. CSJ: Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Data curation; Methodology. ADS: Data curation; Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing; Conceptualization. DM: Writing – review & editing; Conceptualization. ALG: Writing – review & editing; Conceptualization. RB: Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Conceptualization; Visualization. SMS: Funding acquisition; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing; Conceptualization.

Conflicts of Interest

No conflicts of interest have been declared.

References Cited

- Cohen, A., and Cheah C.. . 2015. Interim diets for specialist predators of hemlock woolly adelgids. Entomol. Ornithol. Herpetol. Curr. Res. 4: 153. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, A., and Cheah C.. . 2019. The nature of unnatural insects infrastructure of insect rearing. Am. Entomol. 65: 122–135. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, G. A., Salom S. M., Brewster C. C., Onken B. P., and Kok L. T.. . 2012. Spatiotemporal distribution of the hemlock woolly adelgid predator Laricobius nigrinus after release in eastern hemlock forests. Agric. For. Entomol. 14: 408–418. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M. J., Havill N. P., Jubb C. S., Prosser S. W., B. D.Opell,Salom S. M., and Kok L. T.. . 2014. Contamination delays the release of Laricobius osakensis for biological control of hemlock woolly adelgid: cryptic diversity in Japanese Laricobius spp. and colony-purification techniques. Southeast. Nat. 13: 178–191. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, M. J., Havill N. P., Brewster C. C., Davis G. A., Salom S. M., and Kok L. T.. . 2015. Field assessment of hybridization between Laricobius nigrinus and L. rubidus, predators of Adelgidae. Biol. Control. 82: 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J. R., Minteer C., and Tipping P. W.. . 2016. Differences in seasonal variation between two biotypes of Megamelus scutellaris (Hemiptera: Delphacidae), a biological control agent for Eichhornia crassipes (Pontederiaceae) in Florida. Fla. Entomol. 99: 569–571. [Google Scholar]

- Foley, J. R., McAvoy T. J., Dorman S., Bekelja K., Kring T. J., and Salom S. M.. . 2019. Establishment and distribution of Laricobius spp. (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a predator of hemlock woolly adelgid, within the urban environment in two localities in southwest Virginia. J. Integr. Pest Manag. 10: 30. [Google Scholar]

- Goode, A. B., Minteer C. R., Tipping P. W., Knowles B. K., Valmonte R. J., Foley J. R., and Gettys L. A.. . 2019. Small-scale dispersal of a biological control agent–Implications for more effective releases. Biol. Control. 132: 89–94. [Google Scholar]

- Gouger, R. J. 1971. Control of Adelges tsuage on hemlock in Pennsylvania. Sci. Tree Top. 3: 6–9. [Google Scholar]

- Havill, N. P., and Foottit R. G.. . 2007. Biology and evolution of adelgidae. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 52: 325–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havill, N. P., Montgomery M. E., Yu G., Shiyake S., and Caccone A.. . 2006. Mitochondrial DNA from hemlock woolly adelgid (Hemiptera: Adelgidae) suggests cryptic speciation and pinpoints the source of the introduction to eastern North America. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 99: 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Havill, N. P., Davis G. A., Mausel D. L., Klein J., McDonald R., Jones C., Fischer M., Salom S. M., and Caccone A.. . 2012. Hybridization between a native and introduced predator of Adelgidae: an unintended result of classical biological control. Biol. Control. 63: 359–369. [Google Scholar]

- Havill, N. P., Vieira L. C., and Salom S. M.. . 2016. Biology and control of hemlock woolly adelgid. FHTET-2014-05. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service, Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, Morgantown, WV. [Google Scholar]

- Humble, L. M. 1994. Recovery of additional exotic predators of balsam woolly adelgid, Adelges piceae (Ratzeburg) (Homoptera: Adelgidae), in British Columbia. Can. Entomol. 126: 1101–1103. [Google Scholar]

- JMP®, Version 15 . SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, 1989–2019. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C. E., Hanula J. L., and Braman S. K.. . 2014. Emergence of Laricobius nigrinus (Fender) (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) in the North Georgia Mountains. J. Entomol. Sci. 49: 401–412. [Google Scholar]

- Jubb, C. S., Heminger A. R., Mayfield A. E., Elkinton J. S., Wiggins G. J., Grant J. F., Lombardo J. A., McAvoy T. J., Crandall R. S., and Salom S. M.. . 2020. Impact of the introduced predator, Laricobius nigrinus, on ovisacs of the overwintering generation of hemlock woolly adelgid in the eastern United States. Biol. Control. 143: 104180. [Google Scholar]

- Jubb, C. S., McAvoy T. J., Stanley K. E., Heminger A. R., and Salom S. M.. . 2021. Establishment of the predator, Laricobius nigrinus, introduced as a biological control agent for hemlock woolly adelgid in Virginia, USA. BioControl. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Kantola, T., Tracy J. L., Lyytikäinen-Saarenmaa P., Saarenmaa H., Coulson R. N., Trabucco A., and Holopainen M.. . 2019. Hemlock woolly adelgid niche models from the invasive eastern North American range with projections to native ranges and future climates. IForest. 12: 149–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, A. B., Salom S. M., and Kok L. T.. . 2005. Survival and reproduction of Laricobius nigrinus Fender (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a predator of hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae Annand (Homoptera: Adelgidae) in field cages. Biol. Control. 32: 200–207. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb, A. B., Salom S. M., and Kok L. T.. . 2007. Factors influencing aestivation in Laricobius nigrinus (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a predator of Adelges tsugae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae). Can. Entomol. 139: 576–586. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, J., and Hlavac T.. . 1979. Review of the Derodontidae (Coleoptera: Polyphaga) with New Species from North America and Chile. Coleopt. Bull. 369–414. [Google Scholar]

- Leppla, N. C., and Fisher W. R.. . 1989. Total quality control in insect mass production for insect pest management. J. Appl. Entomol. 108: 452–461. [Google Scholar]

- Leschen, R. A. B. 2011. World review of Laricobius (Coleoptera: Derodontidae). Zootaxa. 2908: 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Mausel, D. L., Salom S. M., Kok L. T., and Fidgen J. G.. . 2008. Propagation, synchrony, and impact of introduced and native Laricobius spp. (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) on hemlock woolly adelgid in Virginia. Environ. Entomol. 37: 1498–1507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausel, D. L., Salom S. M., Kok L. T., and Davis G. A.. . 2010. Establishment of the hemlock woolly adelgid predator, Laricobius nigrinus (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), in the Eastern United States. Environ. Entomol. 39: 440–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mausel, D. L., Van Driesche R. G., and Elkinton J. S.. . 2011. Comparative cold tolerance and climate matching of coastal and inland Laricobius nigrinus (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a biological control agent of hemlock woolly adelgid. Biol. Control. 58: 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield, A. E., Reynolds B. C., Coots C. I., Havill N. P., Brownie C., Tait A. R., Hanula J. L., Joseph S. V., and Galloway A. B.. . 2015. Establishment, hybridization, and impact of Laricobius predators on insecticide-treated hemlocks: exploring integrated management of the hemlock woolly adelgid. For. Ecol. Manag. 335: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Mayfield, A. E., Salom S. M., Sumpter K., Mcavoy T., Schneeberger N. F., and Rhea R.. . 2020. Integrating chemical and biological control of the hemlock woolly adelgid: a resource manager’s guide technology transfer integrated pest management, FHAAST-2018-04. USDA For. Serv. For. Heal. Assess. Appl. Sci. Team, Morgantown, West Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, M. S. 1989. Evidence of a polymorphic life cycle in the hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae (Homoptera: Adelgidae). Ann. Entomol.Soc. Am. 82: 50–54. [Google Scholar]

- McClure, M. S. 1991. Density-dependent feedback and population cycles in Adelges tsugae (Homoptera: Adelgidae) on Tsuga canadensis. Environ. Entomol. 20: 258–264. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald, R., Mausel D., Salom S., and Kok L. T.. . 2011. A case study of a release of the predator Laricobius nigrinus Fender against hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae, Annand, at the urban community forest interface: Hemlock Hill, Lees-McRae College, Banner Elk, North Carolina, pp. 168–175. InOnken B., and Reardon R. (Tech. Coord.), Implementation and Status of Biological Control of the Hemlock Woolly Adelgid. USDA Forest Service FHTET 2011-04. [Google Scholar]

- Messenger, P. S., Wilson F., and Whitten M. J.. . 1976. Variation, fitness, and adaptability of natural enemies, pp. 209–231. InHuffaker C. B. and Messenger P. S. (eds.), Theory and Practice of Biological Control. Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery, M. E., and Lyon S. M.. . 1996. Natural enemies of adelgids in North America: their prospect for biological control of Adelges tsugae (Homoptera: Adelgidae), pp. 89–102. InSalom S. M., Tigner T. C., and Reardon R. C. (eds.), Proceedings of the First Hemlock Woolly Adelgid Review. U.S. Department of Agriculture. Forest Service, Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery M. E., Shiyake S., Havill N. P., and Leschen R. A. B.. . 2011. A new species of Laricobius (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) from Japan with phylogeny and a key for native and introduced congeners in North America. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 104: 389–401. [Google Scholar]

- Mooneyham, K. L., Salom S. M., and Kok L. T.. . 2016. Release and colonization of Laricobius osakensis (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a predator of the hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae. Northeast. Nat. 23: 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . 2019. R: a language and environment for statistical computing.R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL https://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- Salom, S. M., Sharov A. A., Mays W. T., and Gray D. R.. . 2002. Influence of temperature on development of hemlock woolly adelgid (Homoptera: Adelgidae) progrediens. J. Entomol Sci. 37: 166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Salom, Scott, Kok Loke T., McAvoy Tom, and McDonald Richard. . 2011. Field insectary: Concept for future predator production, pp. 195–198. InOnken B., and Reardon R., (eds.), Implementation and status of biological control of the hemlock woolly adelgid. FHTET-2011-04. US Department of Agriculture, Forest Service Forest Health Technology Enterprise Team, Morgantown, WV. [Google Scholar]

- Salom, S., Kok L., Lamb A., and Jubb C.. . 2012. Laboratory rearing of Laricobius nigrinus (Coleoptera: Derodontidae): a predator of the hemlock woolly adelgid (Hemiptera: Adelgidae). Psyche. 2012: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Silcox, C. A. 2002. Using imidacloprid to control hemlock woolly adelgid, pp. 280–287. InOnken B., Reardon R., and Lashomb J. (eds.), Hemlock woolly adelgid in the eastern United States Symposium. U.S. Dep. Agric. For. Serv. Publ., East Brunswick, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Steward, V. B., Braness G., and Gill S.. . 1998. Ornamental pest management using imidacloprid applied with the Kioritz® soil injector. Arboric. 24: 344–346. [Google Scholar]

- Stoetzel, M. B. 2002. History of the introduction of Adelges tsugae based on voucher specimens in the Smithsonian Institute National Collection of Insects, p. 12. InOnken B., Reardon R., and Lashomb J. (eds.), Proceedings of the hemlock woolly adelgid in eastern North America symposium. U.S. Department of Agriculture Forest Service and State University of NJ Rutgers, East Brunswick, NJ. [Google Scholar]

- Story, H. M., Vieira L. C., Salom S. M., and Kok L. T.. . 2012. Assessing performance and competition among three Laricobius (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) species, predators of hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae). Environ. Entomol. 41: 896–904. [Google Scholar]

- Tipping, P. W., Martin M. R., Bauer L., Pokorny E., and Center T. D.. . 2010. Asymmetric impacts of two herbivore ecotypes on similar host plants. Ecol. Entomol. 35: 469–476. [Google Scholar]

- Toland, A., Brewster C., Mooneyham K., and Salom S. M.. . 2018. First report on establishment of Laricobius osakensis (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a biological control agent for hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae), in the Eastern US. Forests. 9: 496. [Google Scholar]

- USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) . 2017. Approval of Laricobius naganoensis (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a Predatory Beetle for Biological Control of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, Adelges tsugae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae), in the Continental United States, Draft Environmental Assessment 2017. Plant Protection and Quarantine, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, United States Department of Agriculture, Riverdale, MD. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, L. C., Mcavoy T. J., Chantos J., Lamb A. B., Salom S. M., and Kok L. T.. . 2011. Host range of Laricobius osakensis (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a new biological control agent of hemlock woolly adelgid (Hemiptera: Adelgidae). Environ. Entomol. 40: 324–332. [Google Scholar]

- Vieira, L., Lamb A., Shiyake S., Salom S., and Kok L.. . 2013. Seasonal abundance and synchrony between Laricobius osakensis (Coleoptera: Derodontidae) and its prey, Adelges tsugae (Hemiptera: Adelgidae) in Japan. Ann. Entomol. Soc. Am. 106: 249–25. [Google Scholar]

- Virginia Tech . 2019. HWA Predator Database – Hemlock Woolly Adelgid. Available from http://hiro.ento.vt.edu/pdb/.

- Wiggins, G. J., Grant J. F., Rhea J. R., Mayfield A. E., Hakeem A., Lambdin P. L., and Galloway A. B.. . 2016. Emergence, Seasonality, and Hybridization of Laricobius nigrinus (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), an Introduced Predator of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (Hemiptera: Adelgidae), in the Tennessee Appalachians. Environ. Entomol. 45: 1371–1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilahi-Balogh, G. M. G., Kok L. T., and Salom S. M.. . 2002. Host specificity of Laricobius nigrinus Fender (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a potential biological control agent of the hemlock woolly adelgid, Adelges tsugae annand (Homoptera: Adelgidae). Biol. Control. 24: 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Zilahi-Balogh, G. M. G., Salom S. M., and Kok L. T.. . 2003a. Development and reproductive biology of Laricobius nigrinus, a potential biological control agent of Adelges tsugae. Biol. Control. 48: 293–306. [Google Scholar]

- Zilahi-Balogh, G. M. G., Salom S. M., and Kok L. T.. . 2003b. Temperature-dependent development of the specialist predator Laricobius nigrinus (Coleoptera: Derodontidae). Environ. Entomol. 32: 1322–1328. [Google Scholar]

- Zilahi-Balogh, G. M. G., Broeckling C. D., Kok L. T., and Salom S. M.. . 2005. Comparison between a native and exotic adelgid as hosts for Laricobius rubidus (Coleoptera: Derodontidae). Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 15: 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Zilahi-Balogh, G. M. G., Humble L. M., Kok L. T., and Salom S. M.. . 2006. Morphology of Laricobius nigrinus (Coleoptera: Derodontidae), a predator of the hemlock woolly adelgid. Can. Entomol. 138: 595–601. [Google Scholar]