Abstract

Tricho-hepatic-enteric syndrome (THES) is a genetically heterogeneous rare syndrome (OMIM: 222470 (THES1) and 614602 (THES2)) that typically presents in the neonatal period with intractable diarrhoea, intra-uterine growth retardation (IUGR), facial dysmorphism, and hair and skin changes. THES is associated with pathogenic variants in either TTC37 or SKIV2L; both are components of the human SKI complex, an RNA exosome cofactor.

We report an 8 year old girl who was diagnosed with THES by the Undiagnosed Disease Program-WA with compound heterozygous pathogenic variants in SKIV2L. While THES was considered in the differential diagnosis, the absence of protracted diarrhoea delayed definitive diagnosis. We therefore suggest that SKIV2L testing should be considered in cases otherwise suggestive of THES, but without the characteristic diarrhoea. We expand the phenotypic spectrum while reviewing the current knowledge on SKIV2L.

Keywords: SKIV2L, Undiagnosed, Next generation sequencing, RNA exosome, SKI complex

1. Introduction

THES is a rare genetic disorder associated with pathogenic variants in SKIV2L or TTC37, both encode for proteins which are part of the RNA SKI (super killer) complex (Fabre et al., 2012). THES typically presents in the neonatal period with intractable diarrhoea, almost always requiring parenteral nutrition, and subsequent poor weight gain and failure to thrive, woolly and brittle hair and facial dysmorphisms (Verloes et al., 1997). Other features are immunodeficiency, skin abnormalities, liver disease, mild intellectual disability, and rarely congenital heart disease. It has an estimated prevalence of 1:1,000,000 (Fabre et al., 2014).

THES, now known to associate with locus heterogeneity (OMIM: 222470 (THES1, formerly syndromic diarrhoea (SD)) and 614602 (THES2)), was first described by Verloes et al. (1997). The first confirmed genetic cause of THES was pathogenic variation in the TTC37 gene (Hartley et al., 2010). Subsequently, SKIV2L pathogenic variants were found to be causative and clinically undistinguishable from the TTC37 aetiology in 2012 by Fabre et al. (2012). Two thirds of reported THES cases are caused by TTC37, and one third by SKIV2L pathogenic variants (Bourgeois et al., 2018); however, SKIV2L pathogenic variants are associated with higher early mortality rate of approximately 30% (Fabre et al., 2012, 2013). THES is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner with complete penetrance (Bourgeois et al., 2018).

Both SKIV2L and TTC37 encode proteins that are part of the human SKI complex which is conserved from yeast to humans and is a cofactor of the RNA exosome, with a role in mRNA degradation (Schneider and Tollervey, 2013).

SKIV2L is located at 6p21.33 and encodes for SKI2W which comprises of 1246 amino acids and contains two helicase domains (ATP-binding and C-terminal) and a DEVH box motif in the first helicase domain. SKIV2L is an ortholog of the yeast ski2.

The human SKI complex consists of 4 proteins including SKI2W (encoded by SKIV2L), TPR (encoded by TTC37), and 2 subunits of WD40-containing domains encoded by WDR61 (Halbach et al., 2013). The SKI complex is a cofactor to the RNA exosome whose role is to mediate RNA surveillance (Schneider and Tollervey, 2013); however, the pathogenetic mechanisms of the THES multi-system phenotype remain to be determined.

2. Clinical findings

We present an 8-year-old girl born to non-consanguineous parents of Australian English/Polish origin. She was born at 34 weeks gestation after a pregnancy complicated by intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), echogenic bowel and pericardial effusion.

2.1. Neonatal period

At birth her weight was 1.865 kg (20th centile), her head circumference was 30.5 cm (29th centile) and her length was 42 cm (10th centile). Her neonatal period was complicated by hypoglycaemia due to transient hyperinsulinemia and requiring treatment with diazoxide. During the neonatal period there were also multiple episodes of unexplained metabolic acidosis which resolved spontaneously. Echocardiography during the neonatal period showed multiple (ventricular septal defects) VSDs, which spontaneously closed.

2.2. Gastrointestinal

She was noted to have raised hepatic enzymes, including alpha feta protein, and a liver ultrasound showed hepatic fibrosis with nodularity. Liver biopsy showed fibrous expansion of portal tracts and moderate chronic inflammation. Hepatic enzymes normalised and repeat ultrasound examinations have shown no progressive changes. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopies performed due to episodes of abdominal pain and poor oral intake revealed ulcerations in the duodenum with biopsies showing non-specific inflammation which symptomatically responded well to courses of antibiotic treatment.

While our proband did not have intractable diarrhoea, she did exhibit feeding problems and episodes of abdominal distension. She required nasogastric feeding and gastrostomy insertion for feeding support.

2.3. Immunology

She had an episode of anaphylaxis to cow’s milk protein formula at six months of age with a subsequent positive skin prick test and serum specific IgE to cow’s milk. During the evaluation of that episode, sensitisation to hen’s egg was identified on skin prick test and egg avoidance was recommended. She tolerated soy protein based formula for a three month period at around 12 months of age; however, this was withheld following an episode of profuse vomiting and diarrhoea associated with metabolic acidosis. On subsequent rechallenge with soy on three separate occasions, most recently at 8 years of age, she developed profuse vomiting 1.5–2 h after ingestion. A diagnosis of food protein induced enterocolitis syndrome (FPIES) to soy was confirmed. The gastrostomy was closed during early childhood. Cow’s milk allergy and egg sensitisation have resolved, and she is currently on a normal diet, other than ongoing soy avoidance.

There was transient neutropenia in the context of a pyrexial illness, however bone marrow examination was normal. Serum immunoglobulins revealed normal IgG and IgM with borderline elevation of IgA and normal IgG subclasses. Response to tetanus toxoid immunisation was normal, however response to pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax 23) was impaired with four-fold rise in post-vaccination titres observed to 7 of the 14 measured serotypes (50%) and with protective titres to only 4 serotypes (29%) (an adequate response is defined as >70% of serotypes with protective titres). Lymphocyte immunophenotyping at 7 years of age demonstrated normal numbers and proportions of T, B, and NK cells, and normal class switched memory B cells. In the absence of a clinical history of recurrent sinopulmonary infections, immunoglobulin replacement therapy was not required.

2.4. Development

Bone age assessment was performed at 3 years old which was significantly delayed. She was started on growth hormone treatment at 5 years old and demonstrated a good response, gaining 3 cm in one year and is currently tracking along the 1st centile. Other than a mild speech delay, cognitive development was normal.

2.5. Clinical genetics

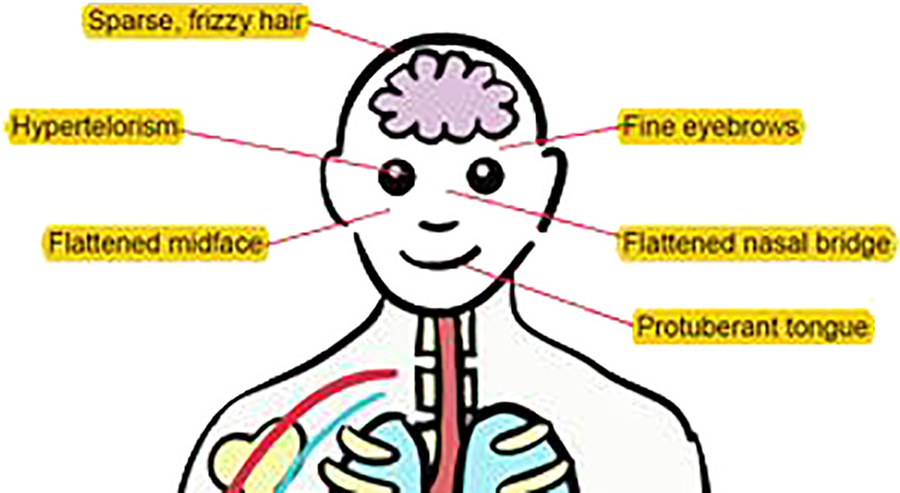

Genetic consultation first occurred at 13 months of age. She was noted to have proportionate short stature with a height and weight below the 1st centile and a head circumference on the 25th centile. Dysmorphic features included hypertelorism, flattened nasal bridge and midface and a protuberant tongue. She was noted to have fine eyebrows and sparse, frizzy hair, with an area of occipital aplasia cutis with a surrounding haemangioma (Supplementary Fig. 1). She was also noted to have a variety of skin abnormalities including prominent dimples over elbows, generalised hypopigmentation from left thigh to lower left abdomen, and café au lait lesions. Although she had sparse, frizzy scalp hair, microscopic examination of the hair shaft did not reveal trichorrhexis nodosa or characteristic fractures.

3. Investigations

The proband was referred to our Undiagnosed Diseases Program (Baynam et al., 2017) at age 7 years. Previous normal investigations included urine metabolic screening, plasma copper and ceruloplasmin. Multiple genetic tests did not reveal an abnormality initially and these included single gene Sanger sequencing of HRAS, PTPN11, and SHOC2, chromosomal microarray (Illumina HumanCytoSNP 12), chromosome fragility studies, 11p15 methylation-sensitive MLPA (MRC Holland) on DNA extracted from peripheral blood and hepatic tissue, and whole exome sequencing with bioinformatically targeted analysis of RASo-pathy genes on genomic DNA (methods available upon request).

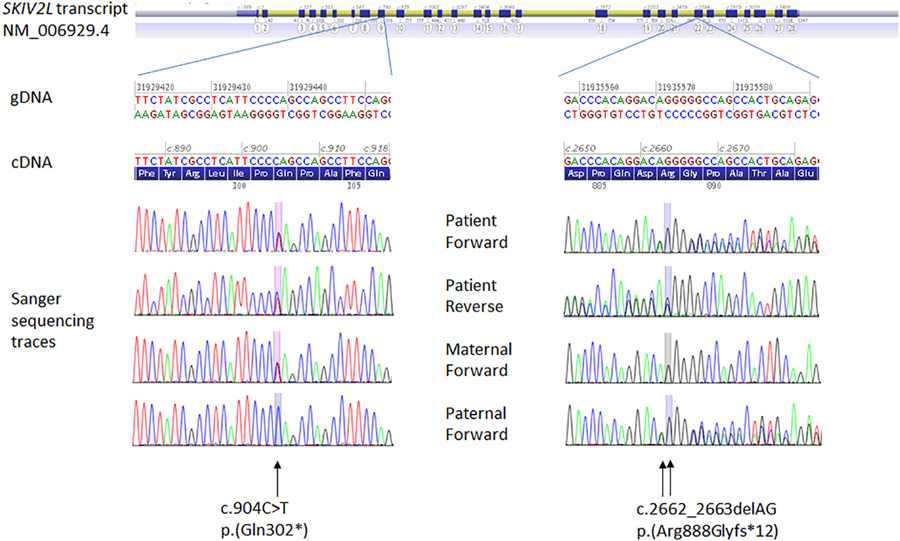

The interdisciplinary discussion at the UDP converged on THES as a potential diagnosis. The diagnosis was confirmed on review of whole exome sequencing data, which revealed 2 pathogenic variants (a nonsense and a frameshift variant) in SKIV2L which were also confirmed by Sanger sequencing in the proband (Fig. 1). These variants were NC_000006.11(GRCh37):g.31929438C>T, NM_006929.4:c.904C>T (p.(Gln302*)), (rs751074844) and NC_000006.11(GRCh37): g.31935570_31935571delAG, NM_006929.4:c.2662_2663delAG (p. (Arg888Glyfs*12))(rs770099418). The c.904C>T nonsense variant has not been described in the literature and has been observed only in one heterozygous individual (South Asian) in the control population database gnomAD (http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/6-31929438-C-T). The frameshift c.2662_2663del variant has been previously reported in the homozygous state in an Australian patient with THES and late onset diarrhoea at 6 months of age (Hosking et al., 2018). It was also described in another homozygous patient with “classical” THES (Fabre et al., 2012) but subsequently erroneously corrected to c.2662_2664del (Bourgeois et al., 2018). The c.2662_2663delAG variants is also a very rare variant, described only in six heterozygous control individuals in the gnomAD database (accessed 18/11/18; http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/variant/6-31935569-CAG-C). Sanger sequencing of parental samples confirmed phase consistent with autosomal recessive inheritance (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sanger sequencing chromatograms for DNA from the proband and her parents. The trio analysis indicates occurrence of the SKIV2L variants in trans in the proband.

Primers used for targeted amplification and sequencing of the gene regions containing the SKIV2L variants are as follows: Forward TGGGTCTGAGGGGAAGAAAG and reverse GATCTGACCTCTGGCCAATAG (exon 9) for NM_006929.4:c.904C>T, and forward GTTGCTTCCTGATTCCTGCCC and reverse CACTACAACCCCACCACTTC (exon 22) for NM_006929.4:c.2662_2663delAG.

4. Discussion

THES is a rare autosomal recessive syndrome characterised by woolly hair, IUGR and facial dysmorphisms (Fig. 2); in nearly all children intractable diarrhoea occurs within the first few months of life. Other features that have been described include liver disease, skin abnormalities, cardiac abnormalities and immunodeficiency.

Fig. 2.

Illustration depicting characteristic features associated with THES.

A recent case series of 96 patients published in 2018 by Bourgeois et al. indicated association in 32% of cases with pathogenic variants in SKIV2L. SKIV2L pathogenic variants consist of frameshift (25%), nonsense (23%), and missense (19%), with no obvious hotspots but speculatively with preferable location of missense variants in the functional domains (Bourgeois et al., 2018).

Diarrhoea was present in 100% of reported cases, associated with failure to thrive (FTT) and need for parenteral nutrition in 85%. In 3 cases, no data was available however previous reports have suggested that diarrhoea is considered a constant feature. Woolly and brittle hair was described in 90% and facial dysmorphisms were seen in 84%. Liver disease was more commonly associated with SKIV2L pathogenic variants compared to TTC37, and has a range of reported phenotypes including fibrosis and cirrhosis. IUGR was a consistent feature with 86% of SKIV2L patients born at under the 10th centile and postnatal growth delay was characteristic for the disorder (Bourgeois et al., 2018). The intractable diarrhoea has been invoked as a main contributor to the postnatal growth issues; however, our proband’s phenotype challenges this notion.

Intra-familial clinical heterogeneity and inconsistent diarrhoea phenotype associated with SKIV2L pathogenic variants has been described in 2016, in 2 Malaysian brothers with compound heterozygous SKIV2L pathogenic variants (one missense and one nonsense variant) (Seah et al., 2016). The siblings were born at <2 kg and developed diarrhoea requiring a period of parenteral nutrition. However, the second born had a milder phenotype with normal hair and was changed from parenteral nutrition to elemental formula. Both were reported to have normal neurocognitive development (Seah et al., 2016). An Australian patient homozygous for the SKIV2L c.2662_2663delAG variant had a delayed diarrhoea with onset at 6 months associated with severe immunodeficiency (Hosking et al., 2018).

Our proband’s cutaneous features were notable and included hypopigmentation and café au lait spots seen in the lower limb to lower abdominal area. This is consistent with previous reports by Monies et al. who described 6 patients of Saudi origin from 3 families with SKIV2L mutations all of which had intractable diarrhoea and woolly hair but also all had hypopigmentation with numerous café au lait lesions restricted to the pelvis and lower limbs (Monies et al., 2015). We suggest that this particular distribution of skin hypopigmentation may be characteristic of this condition.

Immunodeficiency is also variably reported, including poor vaccine responses and susceptibility to viral infections. Our proband exhibited normal protein and impaired polysaccharide vaccine responses. She developed IgE-mediated cow’s milk protein and egg sensitisation, which resolved, followed by persistent FPIES to soy. Cow’s milk protein intolerance and Soy allergy was also described in the case by Seah et al. (2016), although it was not persistent in their case.

Immunological disturbance is being increasingly recognised in THES. We postulate that subtle immune dysregulation may explain the non-specific gastrointestinal inflammation in our patient.

Eckard et al. showed that SKIV2L has a role in negatively regulating Rig-1-like receptors anti-viral response and SKIV2L-depleted cells obtained from patients with THES have been shown to have a strong interferon signature. Accordingly, the authors postulate that these patients would be at increased risk of auto-immune diseases (Eckard et al., 2014). Autoimmunity has not been reported to date, possibly due to the high early mortality of THES. Low immunoglobulin levels and diminished vaccine responses have been reported in about half of affected patients (Bourgeois et al., 2018); however, the abnormalities described appear quite variable and nonspecific. Increased susceptibility to infection is likewise reported.

A recent study using material from a cohort of THES patients, including 3 harbouring SKIV2L pathogenic variants, investigated immune function. The authors didn’t differentiate between the TTC37 or SKIV2L cells in the results or discussion; however, they did find decreased levels of switched memory B cells in all patients. Due to administration of immunoglobulins, the vaccine responses were difficult to assess. They described high incidence of Epstein Barr Viral infections in reported patients, including one with SKIV2L pathogenic variants, and postulated that this was due to an apparent Natural Killer (NK) cell lymphopenia (found in 6 out of 9 patients) and more specifically, the lack of IFN producing NK cells in response to stimuli (Vély et al., 2018).

A striking feature of our proband is absence of intractable diarrhoea. The absence of diarrhoea has been reported in one previous THES case, caused by TTC37 mutations, where there was no diarrhoea but presence of hyperemesis and significant immunodeficiency (Rider et al., 2015). It has been suggested by Bourgeois et al. that patients with SKIV2L pathogenic variants present earlier and are more severely affected (Bourgeois et al., 2018). This is not consistent with our proband or with the reported Malaysian siblings (Seah et al., 2016).

Our proband exhibited intra-uterine growth retardation and subsequent failure to thrive and short stature. After growth hormone therapy, she demonstrated a good response, and while she is still tracking along the 1st centile for height, she has gained 3 cm a year. This report demonstrates that growth hormone therapy could be considered in patients with SKIV2L mutations.

Our proband seems to be following a milder trajectory with milder hepatic abnormalities and absence of intractable diarrhoea. It is difficult to explain the lack of diarrhoea and the milder phenotype based on genotype with prediction of loss-of-function for both variants observed. However, previous case reports, even within the same family, have shown a variable expressivity making it difficult to make a genotype-phenotype correlation.

In conclusion, this case report expands the phenotypic spectrum of SKIV2L mutations, including the first report of THES due to SKIV2L pathogenic variants and absence of the typical intractable diarrhoea. In doing so, it further raises the consideration of molecular testing for THES in cases of poor growth and skin and hair abnormalities, but without intractable diarrhoea. Furthermore, we describe a range of immunological phenomena to add to the knowledge base of the immunological spectrum associated with THES and draw attention to a possible characteristic pattern of hypopigmentation that might provide a diagnostic clue.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the patient and her family for their participation in his study.

The Undiagnosed Disease Program (WA) is supported by the Angela Wright Bennet Foundation and McCusker Charitable Foundation.

DA was supported by a Raine Medical Research Foundation clinical research fellowship (CRF018, project “Diagnostic genomics applications for short stature”).

This review and corresponding Gene Wiki article are written as part of the Gene Wiki review series – a series resulting from a collaboration between the journal GENE and the Gene Wiki Initiative. The Gene Wiki Initiative is supported by the National Institutes of Health (GM089820). Additional support for Gene Wiki reviews is provided by Elsevier, the publisher of GENE. The authors would like to thank the patient and her family for participation of the study and the Raine clinical research fellowship for support of DA.

The corresponding Gene Wiki entry for this review can be found here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SKIV2L.

Abbreviations:

- cm

centimetres

- DNA

deoxyribonucleic acid

- GI

gastrointestinal

- HRAS

Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog gene

- IgE

immunoglobulin type E

- IgG

immunoglobulin type G

- IgM

immunoglobulin type M

- IUGR

intrauterine growth retardation

- kg

kilograms

- MLPA

Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification

- NK

Natural Killer

- OMIN

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man

- PTPN11

tyrosine-protein phosphatase non-receptor type 11 gene

- RNA

ribonucleic acid

- SHOC2

leucine Rich Repeat Scaffold Protein gene

- SKIV2l

Superkiller Viralicidic Activity 2-Like gene

- SKI2W

putative RNA helicase Ski2w

- THES

tricho-enteric-hepatic syndrome

- TPR

tetratricopeptide repeat protein 37

- TTC37

tetratricopeptide repeat domain 37 gene

- VSD

ventricular septal defect

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2019.02.059.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Baynam G, Broley S, Bauskis A, Pachter N, McKenzie F, Townshend S, Slee J, Kiraly-Borri C, Vasudevan A, Hawkins A, Schofield L, Helmholz P, Palmer R, Kung S, Walker CE, Molster C, Lewis B, Mina K, Beilby J, Pathak G, Poulton C, Groza T, Zankl A, Roscioli T, Dinger ME, Mattick JS, Gahl W, Groft S, Tifft C, Taruscio D, Lasko P, Kosaki K, Wilhelm H, Melegh B, Carapetis J, Jana S, Chaney G, Johns A, Owen PW, Daly F, Weeramanthri T, Dawkins H, Goldblatt J, 2017. Initiating an undiagnosed diseases program in the Western Australian public health system. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourgeois P, Esteve C, Chaix C, Béroud C, Lévy N, Fabre A, Badens C, 2018. Tricho-Hepato-Enteric Syndrome mutation update: mutations spectrum of TTC37 and SKIV2L, clinical analysis and future prospects. Hum. In: Mutat [DOI] [PubMed]

- Eckard SC, Rice GI, Fabre A, Badens C, Gray EE, Hartley JL, Crow YJ, Stetson DB, 2014. The SKIV2L RNA exosome limits activation of the RIG-I-like receptors HHS Public Access. Nat. Immunol 15, 839–845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre A, Charroux B, Martinez-Vinson C, Roquelaure B, Odul E, Sayar E, Smith H, Colomb V, Andre N, Hugot J-P, Goulet O, Lacoste C, Sarles J, Royet J, Levy N, Badens C, 2012. REPORT SKIV2L mutations cause syndromic diarrhea, or trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet 90, 689–692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre A, Martinez-Vinson C, Goulet O, Badens C, 2013. Syndromic diarrhea/tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. Orphanet J. Rare Dis 8, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabre A, Breton A, Coste ME, Colomb V, Dubern B, Lachaux A, Lemale J, Mancini J, Marinier E, Martinez-Vinson C, Peretti N, Perry A, Roquelaure B, Venaille A, Sarles J, Goulet O, Badens C, 2014. Syndromic (phenotypic) diarrhoea of infancy/tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. Arch. Dis. Child 99, 35–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbach F, Reichelt P, Rode M, Conti E, 2013. The yeast ski complex: crystal structure and RNA channeling to the exosome complex. Cell 154, 814–826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley JL, Zachos NC, Dawood B, Donowitz M, Forman J, Pollitt RJ, Morgan NV, Tee L, Gissen P, Kahr WHA, Knisely AS, Watson S, Chitayat D, Booth IW, Protheroe S, Murphy S, de Vries E, Kelly DA, Maher ER, 2010. Mutations in TTC37 cause trichohepatoenteric syndrome (phenotypic diarrhea of infancy). Gastroenterology 138, 2388–2398.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosking LM, Bannister EG, Cook MC, Choo S, Kumble S, Cole TS. 2018. Trichohepatoenteric syndrome presenting with severe infection and later onset diarrhoea. J. Clin. Immunol 38: 1–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monies DM, Rahbeeni Z, Abouelhoda M, Naim EA, Al-Younes B, Meyer BF, Al-Mehaidib A, 2015. Expanding phenotypic and allelic heterogeneity of tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr 60, 352–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rider NL, Boisson B, Jyonouchi S, Hanson EP, Rosenzweig SD, Casanova J-L, Orange JS, 2015. Corrigendum: novel TTC37 mutations in a patient with immunodeficiency without diarrhea: extending the phenotype of trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Front. Pediatr 3, 10–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider C, Tollervey D, 2013. Threading the barrel of the RNA exosome. Trends Biochem. Sci 38, 485–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seah W, Ming K, Terng R, Yee S, Pin B, Heng K, 2016. Novel mutations in SKIV2L and TTC37 genes in Malaysian children with trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Gene 586, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vély F, Barlogis V, Marinier E, Coste M-E, Dubern B, Dugelay E, Lemale J, Martinez-Vinson C, Peretti N, Perry A, Bourgeois P, Badens C, Goulet O, Hugot J-P, Farnarier C, Fabre A, 2018. Combined immunodeficiency in patients with trichohepatoenteric syndrome. Front. Immunol 9, 1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verloes A, Lombet J, Lambert Y, Hubert AF, Deprez M, Fridman V, Gosseye S, Rigo J, Sokal E, 1997. Tricho-hepato-enteric syndrome: further delineation of a distinct syndrome with neonatal hemochromatosis phenotype, intractable diarrhea, and hair anomalies. Am. J. Med. Genet 68, 391–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.