ABSTRACT

Introduction: Vaccination is among the most important areas of progress in the worldwide history of public health. However, a crescent wave of anti-vaccine groups has grown in Western countries, especially in Italy, in the last two decades. Our aim was to evaluate adult’s hesitancy and knowledge about vaccines and related diseases in Trentino-Alto Adige -the Italian region with the lowest vaccination coverages.

Methods: We administered self-answered structured questionnaires in three malls in the Trentino province in June 2019. We collected demographic data and information on knowledge about vaccines, infectious diseases and attitude in seeking health information. We utilized a descriptive and multivariate analysis to investigate factors associated with vaccine hesitancy.

Results: We collected 567 questionnaires, 18% of the people interviewed were hesitant toward vaccination and 16% were against mandatory vaccination. In the multivariate analysis a poor level of information, being younger than 60 years and being against compulsory vaccination were associated with vaccine hesitancy. Regarding information about vaccines, 76.5% of the people relied on physicians, and/or 49% navigated the internet, while social media are used by 16% of the study population. Though 41.5% searched information on official sites, only 14% knew the website VaccinarSì and 4.7% had visited it.

Discussion: Compared to a previous study conducted in all of Italy except Trentino Alto Adige, the level of vaccination hesitancy was higher. It is important to utilize health professionals, the internet and especially social media to spread scientific information about vaccination.

KEYWORDS: Vaccination, mandatory, information, Trentino, VaccinarSì

Introduction

Vaccination is among the most important areas of progress in the worldwide history of public health.1 Nevertheless, a growing number of anti-vaccine groups has spread in Western European countries, especially in Italy2 in the last two decades. In 2016, a 67-country survey conducted by the Vaccine Confidence Project (VCP) found that the European region had lower confidence in the safety of vaccines than other world regions.3 Moreover, the European region accounted for seven of the ten countries with the lowest levels of safety-based confidence issues3 four of which (France, Greece, Slovenia, and Italy) are in the European Union (EU).4 In 2017 there was a significant outbreak of measles in Italy, due to a large pool of measles-susceptible people resulting from a low rate of measles vaccination. Measles vaccine rates were very low in the years following its introduction in Italy in 1976 and this has led to large vaccination gaps among adolescents and young adults, and a constantly increasing median age of reported cases.5

A clear inverse correlation between measles incidence and vaccine coverage can be observed in the years following the introduction of a single-antigen measles vaccine in 1976.5,6 The MMR vaccine was phased into Italy in its current formulation in the early 1990 s, followed in 1999 by the recommendation that a second vaccine dose be administered in regions with over 80% coverage for the first dose. In 2003, in an attempt to eliminate endemic measles and rubella transmission by 2007, the Italian Ministry of Health launched the National Plan of Measles and Congenital Rubella Elimination (PNEMoRC), recommending the introduction of two MMR doses in all Italian regions with the target of achieving 95% vaccine coverage (http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_730_allegato.pdf, 2003). Although vaccination rates uptake for the first dose improved after implementation of the first national elimination plan in 2003, reaching 90.6% in 2010, the target of 95% was never reached. In the following years, MMR vaccine coverage continued to increase among the Italian population, with single-dose coverage reaching a maximum of 90.6% in 2010. Worryingly, MMR coverage, however, started to decline steadily after 2010, reaching a minimum of 85.2% in 2015.7

Administratively, the Italian republic is divided into 19 regions and two autonomous provinces, Trentino and Bolzano,8 forming the region of Trentino-Alto Adige. Each province has legislative power and is not subject to the medical policies9 of the region. In Italy only diphtheria, tetanus, poliomyelitis and hepatitis B vaccines were mandatory until 2008.10 At that time Veneto became the « test province » to try to eliminate any mandatory vaccines and attempt to keep high levels of vaccination coverage through appropriate information campaigns for the population.10 This attempt unfortunately lead to terrifying decline in immunization levels not only in Veneto but also in other regions including Trentino-Alto Adige where the vaccination coverage had already been the lowest.9 It can be assumed that the political measures adopted in Veneto influenced the public opinion about immunization requirements also within other Italian regions. Consequently, in 2017 the National Prevention Vaccination Plan was enacted making 10 vaccines mandatory in all of Italy11 to respect the international guidelines for vaccination published by the WHO12 and give the chance to every child born in Italy to grow without any infectious disease preventable by vaccines. This was the so called Lorenzin decree. This sudden turnaround in national immunization policy has increased controversy over the social and ethical aspects of vaccination and cannot ensure long-term success.10

Unfortunately, the political climate in Italy favored skepticism: in 2015 the Five Star Movement party, one of the most powerful political parties in Italy, proposed a law against vaccinations, citing “the link between vaccinations and specific illnesses such as leukemia, poisoning, inflammation, immunosuppression, inheritable genetic mutations, cancer, autism and allergies.”

Again, during the campaign for March 2018’s general election, the hard-right Lega and the eclectic Five Star Movement (M5 s) both doggedly opposed the vaccination policy, repeating pseudoscientific objections to MMR vaccinations. And when these two parties formed a new government in June, new interior minister called the set of ten vaccinations “useless, in some cases dangerous if not harmful,” without specifying the grounds his views were based upon. As a result, the small but virulent anti-vaccine movement has been buoyed by the rise to power of a populist coalition skeptical about vaccinations.

This is the reason why reliable scientific sources of information within the internet and particularly social networks have been strengthened. Among the proposed initiatives, the VaccinarSì portal was created in 2013 by the Italian Society of Hygiene13,14 and continued its development by creating specific regional websites. Its objective is to improve access for the general population to quality affordable scientific information for the general public. It details the benefits and risks of each vaccination, the infectious diseases against which they protect, answers to parents’ frequent questions about the vaccination, side effects, schedule of information meetings, etc. It also has a Facebook page, Youtube, Twitter and a blog. An analysis of the use of the national portal, conducted 6 years after its creation (Bordin et al 2019, being published on Annali di Igiene) revealed a rather satisfying popularity of the website (it is very frequented), mainly among health professionals, but a continuous gradual decline of user’s level of engagement with the portal (people stay always less time on the website, visit less pages and tend to immediately visit another website after this one).

The aim of our study was to determine the knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding vaccination of Trentino-Alto Adige inhabitants (as it is the region with the lowest vaccine rates), two years after the change of vaccination policy11 and six years after the creation of the VaccinarSì national website, and to identify risk factors for immunization hesitancy. Our ultimate intention was to adapt the content and the presentation of the new VaccinarSì provincial portal [available at the URL: www.vaccinarsintrentino.org] to the survey results.

Material and methods

Study design and population

We devised a cross-sectional and questionnaire based descriptive study on Knowledge Attitudes and Practices (KAP) about vaccination. The questionnaires were administered in three shopping centers: in Trento, Riva del Garda and Rovereto. These settings were chosen because they are highly frequented public places. The study population consisted of adults over 18 years, residing in the Trentino-Alto Adige region and visiting one of the three shopping centers between June 25, 2019 and July 5, 2019. All adults who were in the shopping centers at the time of the survey and walked close to our stand at the main entrance were therefore selected and invited to respond to our survey. We explained that we were working to understand the opinion of the population of Trentino about vaccination. They were asked if they would answer our anonymous questionnaire.

Sampling

In order to estimate vaccination hesitancy with a precision of 3%, under the assumption that about 15% of respondents were going to be hesitant,15 the sample size required for our survey was 544 persons.

Questionnaire

The questionnaire was a computerized, anonymous, standardized and self-administered electronic case report form (eCRF). It was provided through dedicated tablets and the data was collected directly on the survey software. It consisted of 43 closed or semi-closed questions, focused, written in simple language, not judgmental or taking position. In the case of no-response to a question, an alert appeared to remind the respondent to answer the question, otherwise it was impossible to go further. When a question was not understood, medical staff were available for clarification. For those people who could not dedicate the time needed to complete the entire questionnaire, we collected a minimum of usable information consisting of the first 6 questions (hereinafter referred to as “short version”). The entire questionnaire is reported in Appendix. At the end of the questionnaire completion, the participants were given a leaflet containing vaccine information, the Italian vaccination schedule and a link to the “VaccinarSì” website to get more information. Prior to administration, the questionnaire had been tested on 30 people randomly selected, in order to evaluate the intelligibility of questions and instructions as well as to test the time needed for its completion.

Variables collected

To choose the most relevant variables to collect we based our questions on tools proposed by the SAGE Working group on Vaccine Hesitancy.16 The short version of the questionnaire only included information on sex, age, attitude toward vaccines and vaccination requirements, whether or not he/she would accept vaccinations if not mandatory and if he/she knew the VaccinarSì website. The long questionnaire was divided into seven sections: one for socio-demographic data (number of young or very young children, marital status, province of residence, country of origin, professional category, level of education); a section on attitudes and 5 sections on knowledge and practices related to vaccines, the related diseases and the sources of information used by respondents.

Face validity was guaranteed by our qualitative evaluation at the moment of the completion of the questionnaire.17 To provide content validity, we made sure that the items or tests covered all the main reasons of hesitation by comparing them to the SAGE recommendations;16 that the items covered these different aspects proportionally; that the instrument did not contain irrelevant tests or items thanks to the pilot study.

An overall knowledge score was then created based on the correct answers to the questions 25, 27 to 30 and 33 to 37 assigning 1 point per correct answer. The knowledge was regarded good, intermediate or bad for overall scores between 8 to 10, 5–8 and 0–5 respectively (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Description of knowledge about vaccines based on vaccination hesitancy. Data collected though long questionnaires, n = 396

| Total (n = 396) |

Hesitant (n = 73, 18.4%) |

Non hesitant (n = 323, 81.6%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | Crude OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Knows how a vaccine works | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 73 | 18.4 | 26 | 35.6 | 47 | 14.6 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 323 | 81.6 | 47 | 64.4 | 276 | 85.4 | 0.31 | 0.17–0.54 | |

| Would like to know more | 0.427 | ||||||||

| Maybe | 92 | 23.2 | 22 | 30.2 | 70 | 21.7 | 1 | ||

| No, not interested | 38 | 9.6 | 7 | 9.6 | 31 | 9.6 | 0.72 | 0.28–1.86 | |

| No, do not need | 41 | 10.4 | 8 | 12.0 | 33 | 10.2 | 0.77 | 0.31–1.91 | |

| Yes | 225 | 56.8 | 36 | 49.3 | 189 | 58.5 | 0.61 | 0.33–1.1 | |

| Knows what herd immunity is | 0.02 | ||||||||

| Maybe | 72 | 18.2 | 16 | 21.9 | 56 | 17.3 | 1 | ||

| No | 114 | 28.8 | 29 | 39.7 | 85 | 26.3 | 1.19 | 0.6–2.4 | |

| Yes | 210 | 53.0 | 28 | 38.4 | 182 | 56.3 | 0.54 | 0.27–1.07 | |

| Adverse effects from food vs vaccine | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Food | 284 | 71.7 | 38 | 52.1 | 246 | 76.2 | 1 | ||

| Vaccine | 17 | 4.3 | 7 | 9.6 | 10 | 3.1 | 4.53 | 1.6–12.62 | |

| Same frequency | 15 | 3.8 | 9 | 12.3 | 6 | 1.9 | 9.71 | 3.27–28.8 | |

| Does not know | 80 | 20.2 | 19 | 26.0 | 61 | 18.9 | 2.02 | 1.09–3.74 | |

| Vaccine for rare diseases | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 31 | 7.8 | 16 | 21.9 | 15 | 4.6 | 1 | ||

| Does not know | 29 | 7.3 | 15 | 20.5 | 14 | 4.4 | 1 | 0.36–2.76 | |

| Yes | 336 | 84.8 | 42 | 57.5 | 294 | 91.0 | 0.13 | 0.06–0.29 | |

| Why several vaccines at the same time | 0.55 | ||||||||

| Maybe | 75 | 18.9 | 11 | 15.1 | 64 | 19.8 | 1 | ||

| No | 198 | 50.0 | 40 | 54.8 | 158 | 48.9 | 1.47 | 0.71–3.05 | |

| Yes | 123 | 31.1 | 22 | 30.1 | 101 | 31.5 | 1.27 | 0.57–2.79 | |

| Knowledge of alternatives to vaccines | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Yes | 340 | 85.9 | 57 | 78.1 | 283 | 87.6 | 0.5 | ||

| Knowledge of tetanus | 0.23 | ||||||||

| Yes | 231 | 58.3 | 38 | 52.1 | 193 | 59.8 | 0.74 | ||

| Knowledge of measles | 0.27 | ||||||||

| Yes | 292 | 73.7 | 50 | 68.5 | 242 | 74.9 | 0.73 | 0.42–1.27 | |

| Knowledge of pertussis | 0.12 | ||||||||

| Yes | 243 | 61.4 | 39 | 53.4 | 204 | 63.2 | 0.67 | 0.41–1.14 | |

| Knowledge of available vaccines° | 0.47 | ||||||||

| Yes | 185 | 50.0 | 17 | 46.5 | 103 | 50.8 | 0.84 | 0.53–1.35 | |

| Knowledge score* | 0.43 | ||||||||

| Good | 124 | 31.3 | 24 | 32.9 | 100 | 31.0 | 1 | ||

| Bad | 117 | 29.5 | 25 | 34.2 | 92 | 28.5 | 3.19 | 1.63–6.24 | |

| Intermediate | 155 | 39.1 | 24 | 32.9 | 131 | 40.5 | 1.34 | 0.65–2.76 | |

| Concordance real level/estimated level | 0.09 | ||||||||

| No | 148 | 37.4 | 21 | 28.8 | 127 | 39.3 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 248 | 62.6 | 52 | 71.2 | 196 | 60.7 | 1.6 | 0.92–2.79 | |

° The knowledge of available vaccines was considered as the acknowledgment of at least 6 existing vaccines and no more than one non-existing vaccine

* The knowledge score was created with the answers to the following questions: “Do you know how a vaccine works?” “Do you know what herd immunity is?” “Are the side effects of vaccines more or less common than those due to food?” “Do you think it is useful to vaccinate against diseases we don’t hear more about anymore?” “Do you know why several vaccines are made at the same time?” “What are the alternatives or supplements to vaccines to prevent infectious diseases in general?” “Do you know 2 symptoms or complications of tetanus? Measles? Whooping cough? For which of the following diseases are vaccines?”. If the score was greater than 8 out of 10, the knowledge was considered good, between 5 and 7 as intermediate, and less than 5 insufficient.

Data analysis

The variable of interest in our study was the hesitation toward vaccines.

It usually refers to refused or delayed vaccination in a context of vaccines availability.18 Because of the difficulty in collecting this information in the framework of our study, we asked participants to self- define their attitude about vaccines, by answering the question “what kind of attitude do you think you have about vaccines? “. Those responding “against” or “doubtful” or “not sufficiently informed” were considered to be hesitant about vaccination.

The explanatory variables that we collected were age, sex, education attainment, employment, number of children, geographic origin, living environment (urban or rural), and attitudes, knowledge, and seeking behavior regarding vaccines. We investigated the knowledge of the VaccinarSì website and the satisfaction with it. We performed a descriptive analysis of the characteristics of the whole studied population and an analysis according to their hesitation regarding vaccination. The variable “age” was transformed into a categorial variable using categories based on quartiles (18–33, 34–43, 44–59, 60 and upper). We used a t-Student’s test to compare the quantitative variables and a Chi2 or Fisher test for the qualitative variables. In all the analyzes, a p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

A multivariate logistic regression analysis was then performed. We included in the multivariate models the explanatory variables whose p-value in the univariate analysis was equal to or lower than 0.2. Through a manual descending procedure, we determined which covariates include in the final model. This procedure allowed us to better understand possible modifiers of effect or confusion factors. We did not stratify. We used the Hosmer and Lemeshow adequacy tests and the deviance residue method to check the adequacy of our model. The statistical analyzes were performed by the RStudio Version 1.1.463 software. All tests were two sided.

Results We collected a total of 567 questionnaires including 396 (70%) entirely completed and 171 (30%) short version consisting of the first six questions (the 30 adults of the pilot study were not taken into account for this analysis). The response rate for both kinds of questionnaires was 100% (people could not pass a question because they had an alert blocking them from going on to the next question). The data collected through the short version of the questionnaire according to vaccination hesitancy are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of variables by vaccination reluctance in the 3 Shopping Centers in Italy, June-July 2019, long questionnaire, n = 567

| Total (n = 567) |

Hesitant (n = 106, 18.7%) |

Non hesitant (n = 461, 81.3%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | N | % | n | % | Crude OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Age (years) | 0.15 | ||||||||

| Mean | 46.3 | 44.4 | 46.7 | 0.99 | 0.97–1.00 | ||||

| Standard deviation | 15.5 | 13.8 | 15.8 | ||||||

| Age rank | 0.03 | ||||||||

| 18 to 33 | 157 | 27.7 | 32 | 30.2 | 125 | 27.1 | 1 | ||

| 34 to 43 | 129 | 22.8 | 20 | 18.9 | 109 | 23.6 | 0.72 | 0.39–1.33 | |

| 44 to 59 | 140 | 24.7 | 36 | 34.0 | 104 | 22.6 | 1.35 | 0.79–2.33 | |

| ≥ 60 | 141 | 24.9 | 18 | 17.0 | 123 | 26.7 | 0.57 | 0.3–1.07 | |

| Sex | 0.68 | ||||||||

| Woman | 368 | 65.0 | 67 | 63.2 | 301 | 65.3 | 1 | ||

| Man | 199 | 35.0 | 39 | 36.8 | 160 | 34.7 | 1.1 | 0.71–1.7 | |

| Agreement with obligation | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 91 | 16.0 | 63 | 59.4 | 28 | 6.1 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 476 | 84.0 | 43 | 40.6 | 433 | 93.9 | 0.04 | 0.03–0.08 | |

| Would make the vaccination without obligation | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 35 | 6.2 | 31 | 29.2 | 4 | 0.9 | 1 | ||

| Yes all | 399 | 70.4 | 18 | 17.0 | 381 | 82.6 | 0.01 | 0.01–0.02 | |

| Only a few ones | 133 | 23.5 | 57 | 53.8 | 76 | 16.5 | 0.1 | 0.03–0.29 | |

| Knowledge of the website VaccinarSì | 0.57 | 0.57 | |||||||

| No | 488 | 86.1 | 93 | 87.7 | 395 | 85.7 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 79 | 13.9 | 13 | 12.3 | 66 | 14.3 | 0.84 | 0.44–1.58 | |

| VaccinarSì ever consulted n = 79 * | 0.66 | 0.66 | |||||||

| No | 52 | 65.8 | 7 | 53.8 | 45 | 65,8 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 27 | 34.2 | 6 | 46.2 | 21 | 34.2 | 1.23 | 0.49–3.11 | |

*Numbers for this characteristicsdo not add up to the total number of the study population due to the fact that only 79 people knew the website

Overall, 106 (18.7%) persons have been defined hesitant toward vaccination and the prevalence of participants completing the entire questionnaire did not differ significantly between hesitant people and non hesitants (respectively 69% and 70%, p = .8).

There was not any significant difference in regard to gender or age distribution, with the exception of a significantly higher proportion of under-60 years old among hesitant participants (respectively 84.9% vs 75.5%, p = .03). The average time spent answering the entire questionnaire was 9 minutes, and 1 minute to complete the short version, without any significant difference within the two groups.

Further socio-demographic data of the participants completing the entire questionnaires are reported in Table 2. No significant difference emerged with regard to hesitation to vaccination except for the professional category with a higher proportion of unemployed people among those who were hesitant.

Table 2.

Description of socio-demographic variables according to the hesitancy to vaccination. Data collected through long questionnaires n = 396

| Total (n = 396) |

Hesitant (n = 73, 18.4%) |

Non hesitant (n = 323, 81.5%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | Crude OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Province | 0.29 | ||||||||

| Trento | 384 | 97.0 | 71 | 97.3 | 313 | 97 | 0.57 | 0.11–2.98 | |

| Other | 7 | 1.7 | 2 | 1.7 | 5 | 1.5 | 1 | ||

| Country of origin | 0.69 | ||||||||

| Africa | 13 | 3.3 | 4 | 5.5 | 9 | 2.8 | 1.33 | 0.26–6.83 | |

| America | 12 | 3.0 | 3 | 4.1 | 9 | 2.8 | 1 | 0.17–5.63 | |

| Asia | 4 | 1.0 | 1 | 1.4 | 3 | 0.9 | 1 | 0.08–12.5 | |

| Italy | 351 | 88.6 | 1 | 83.3 | 290 | 89.8 | 0.63 | 0.2–2 | |

| Other European country | 16 | 4.0 | 4 | 5.5 | 12 | 3.7 | 1 | ||

| Living environment | 0.34 | ||||||||

| Urban | 114 | 28.8 | 17 | 23.3 | 97 | 30.0 | 1 | ||

| Rural | 131 | 33.1 | 29 | 39.7 | 103 | 31.6 | 1.61 | 0.84–3.14 | |

| Peri-urban | 151 | 38.1 | 27 | 37.0 | 124 | 38.4 | 1.24 | 0.64–2.41 | |

| Civil status | 0.1 | ||||||||

| Single or widow | 92 | 23.0 | 22 | 30.1 | 70 | 21.7 | 1 | ||

| Engaged | 304 | 77.0 | 51 | 69.9 | 253 | 78.3 | 0.61 | 0.34–1.1 | |

| Parents with | |||||||||

| Children < 15 yrs old | 166 | 42.0 | 28 | 38.4 | 138 | 42.7 | 0.83 | 0.5–1.4 | 0.49 |

| Children < 3 yrs old | 66 | 16.6 | 11 | 16.7 | 55 | 17.0 | 0.86 | 0.43–1.75 | 0.68 |

| Pregnant | 0.13 | ||||||||

| No | 389 | 98.3 | 70 | 95.9 | 319 | 98.8 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 7 | 1.7 | 3 | 4.1 | 4 | 1.2 | 3.42 | 0.75–15.6 | |

| Educational attainment | 0.23 | ||||||||

| PhD/Master degree | 32 | 8.1 | 3 | 4.1 | 29 | 9.0 | 1 | ||

| Bachelor | 106 | 26.8 | 19 | 26.0 | 87 | 26.9 | 2.11 | 0.58–7.65 | |

| High school graduation | 199 | 50.3 | 43 | 58.9 | 156 | 48.3 | 2.66 | 0.77–9.17 | |

| PSAT * | 55 | 13.9 | 8 | 11.0 | 47 | 14.6 | 1.65 | 0.4–6.71 | |

| Occupation | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Agriculture | 8 | 2.0 | 1 | 1.4 | 7 | 2.2 | 1 | ||

| Artisan | 7 | 1.8 | 3 | 4.1 | 4 | 1.2 | 5.25 | 0.4–68.95 | |

| Housewife | 24 | 6.1 | 2 | 2.7 | 22 | 6.8 | 0.64 | 0.05–8.12 | |

| Merchant | 11 | 2.8 | 2 | 2.7 | 9 | 2.8 | 1.56 | 0.12–20.8 | |

| Manager | 12 | 3.0 | 2 | 2.7 | 10 | 3.1 | 1.4 | 0.11–18.6 | |

| Unemployed | 14 | 3.5 | 9 | 12.3 | 5 | 1.5 | 12.6 | 1.2–133.9 | |

| Employee | 91 | 23.0 | 19 | 26.0 | 72 | 22.3 | 1.85 | 0.21–15.9 | |

| Teacher | 29 | 7.3 | 3 | 4.1 | 26 | 8.0 | 0.81 | 0.07–9.0 | |

| Free-lance | 26 | 6.6 | 6 | 8.2 | 20 | 6.2 | 2.1 | 0.2–20.64 | |

| Worker | 42 | 10.6 | 8 | 11.0 | 34 | 10.5 | 1.65 | 0.18–15.3 | |

| Retired | 51 | 12.9 | 1 | 1.4 | 50 | 15.5 | 0.14 | 0.01–2.5 | |

| Health professional | 28 | 7.1 | 7 | 9.6 | 21 | 6.5 | 2.33 | 0.24–22.4 | |

| Student | 16 | 4.0 | 1 | 1.4 | 15 | 4.6 | 0.47 | 0.03–8.6 | |

* Preliminary National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test

Attitudes

Among hesitant people: 55.7% declared to be suspicious and 33% admitted they lacked information whereas only 11.3% stated to be completely against vaccination.

As regards attitude toward vaccination, the vast majority of the respondents thought that vaccines were effective, safe, without any important side effects and useful for personal or public health (Table 3). Just a small proportion of hesitants were convinced that vaccines are not effective (6.8%) but a considerable proportion of them were convinced that vaccines are not useful (32.9%) and have important side effects (41.1%). Forty-five-point seven percent of hesitants suggested that vaccines could cause autism, and/or contain mercury and/or weaken the immune system. The hesitants showed significantly less confidence in the efficacy, safety, and usefulness of vaccines than the non hesitants, and were more often victims of fake news. People who chose not to vaccinate gave as a reason the fear of side effects, the mistrust toward the scientific community, or the absence of obligation.

Table 3.

Description of attitudes toward vaccines according to vaccination hesitancy. Data collected through the compilation of the entire questionnaire

| Total (n = 396) |

Hesitant (n = 73, 18.4%) |

Non hesitant (n = 323, 81.5%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | Crude OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Confidence with efficiency | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 347 | 87.6 | 35 | 47.9 | 312 | 96.6 | 1 | ||

| No | 6 | 1.5 | 5 | 6.8 | 1 | 0.3 | 44.5 | 5.0–392.4 | |

| Does not know | 43 | 10.9 | 33 | 45.2 | 10 | 3.1 | 29.42 | 13.3–64.7 | |

| Confidence with safety | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 290 | 73.2 | 17 | 24.7 | 272 | 84.2 | 0.01 | 0–0.05 | |

| No | 83 | 5.8 | 19 | 26.0 | 4 | 1.2 | 1 | ||

| Does not know | 23 | 21.0 | 36 | 49.3 | 47 | 14.6 | 0.16 | 0.05–0.52 | |

| Confidence with utility | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 363 | 91.7 | 49 | 67.1 | 314 | 97.2 | 0.06 | 0.03–0.13 | |

| No | 33 | 8.3 | 24 | 32.9 | 9 | 2.8 | 1 | ||

| Conviction of adverse effects | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Important | 45 | 11.4 | 30 | 41.1 | 15 | 4.6 | 1 | ||

| Light | 226 | 57.1 | 26 | 35.6 | 200 | 61.9 | 0.06 | 0.03–0.14 | |

| Does not know | 72 | 18.2 | 16 | 21.9 | 56 | 17.3 | 0.14 | 0.06–0.33 | |

| Without adverse effects | 53 | 13.4 | 1 | 1.4 | 52 | 16.1 | 0.01 | 0–0.08 | |

| Fake news victim* | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| No | 215 | 54.3 | 12 | 16.4 | 203 | 62.8 | 1 | ||

| Yes | 181 | 45.7 | 61 | 83.6 | 120 | 37.2 | 8.6 | 4.4–16.6 | |

* have been influenced by false messages such as: link between autism and vaccination, presence of mercury in vaccines, risk of weakening of the immune system by vaccines

Concerning attitudes toward the immunization obligation, 16% of all respondents stated to be against and 29.7% declared they would not have accepted the vaccines or would have received only a few of them if they were not mandatory for admission to kindergarten (Table 1).

Knowledge

Regarding the level of knowledge, significantly more hesitant people admitted not knowing how a vaccine works; and, although not significantly, fewer of them would like to know. (Table 4).

The concept of herd immunity was not widely known as well as the reason for vaccine combinations or co- administration. A significantly higher proportion of non-hesitant people claimed to know the concept of herd immunity, were aware that severe adverse reactions following food ingestion are much more likely than that caused by vaccines; and that it is still important to vaccinate even against now rare diseases.

Less than one third of the study population knew why many vaccines are co-administered or combined in the same injection. In this group there was no difference in their attitude of hesitancy. Almost 14% of those who hesitated believed that combination vaccines were a marketing invention of the pharmaceutical industry.

Hesitant people had poorer knowledge of alternatives to fight infectious diseases (hand washing, isolation of sick people, antibiotics, immunity acquired by the disease) and were more likely to use at least one of the following nonscientific strategies: homeopathy, aromatherapy, living in contact with nature, physical activity and organic food.

There was no significant difference in the overall knowledge score as well as in the knowledge of tetanus, measles, whooping cough (pertussis) within the two groups. The best-known disease was measle whereas tetanus was known by just slightly more than a half of the respondents. The match between perceived knowledge level and the level estimated by the score was 62.6%: on third overestimated their level of knowledge.

Practice

The most used sources of information and seeking behavior are reported in Table 5. Half of the people acquired information about vaccines on the internet and 16% from social networks. Those who were hesitant were significantly less likely to seek information from a physician and more likely to find information on media and social networks and to feel that the information already received was contradictory. Claiming to have received clear information was strongly associated with the absence of hesitation.

Table 5.

Description of access to information on vaccines according to hesitation or no, in the 3 shopping centers in Italy, June-July 2019, n = 396

| Total (n = 396) |

Hesitant (n = 73, 18.4%) |

Non hesitant (n = 323, 81.6%) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n | % | n | % | n | % | Crude OR | 95% CI | P value |

| Information by doctor | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Yes | 303 | 76.5 | 49 | 67.1 | 254 | 78.6 | 0.55 | 0.32–0.97 | |

| Information on media | 0.04 | ||||||||

| Yes | 185 | 46.7 | 42 | 57.5 | 143 | 44.3 | 1.71 | 1.02–2.8 | |

| Information on internet | 0.34 | ||||||||

| Yes | 197 | 49.7 | 40 | 54.8 | 157 | 48.6 | 1.28 | 0.77–2.13 | |

| Information on official sites | 0.64 | ||||||||

| Yes | 164 | 41.4 | 32 | 43.8 | 132 | 40.9 | 1.13 | 0.68–1.9 | |

| Information on social network | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Yes | 63 | 15.9 | 23 | 31.5 | 40 | 12.4 | 3.25 | 1.8–5.9 | |

| Clear information | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Contradictory information | 48 | 12.1 | 21 | 28.8 | 27 | 8.4 | 1 | ||

| No | 94 | 23.7 | 28 | 38.4 | 66 | 20.4 | 0.55 | 0.3–1.22 | |

| Does not know | 60 | 15.2 | 12 | 16.4 | 48 | 14.9 | 0.32 | 0.14–0.7 | |

| Yes | 194 | 49.0 | 12 | 16.4 | 182 | 56.3 | 0.08 | 0.04–0.2 | |

| Recent information | 0.12 | ||||||||

| No | 203 | 51.1 | 38 | 52.1 | 165 | 51.1 | 1 | ||

| Does not know | 23 | 5.8 | 8 | 11.0 | 15 | 4.6 | 2.32 | 0.92–5.9 | |

| Yes | 170 | 43.1 | 27 | 37.0 | 143 | 44.3 | 0.8 | 0.48–1.4 | |

The VaccinarSì website was known by 13.9% (79/567) of the respondents while only 4.7% of them had visited it. Two people did not find it useful because of the graphic or overly complicated language (Table 1).

Multivariate analysis

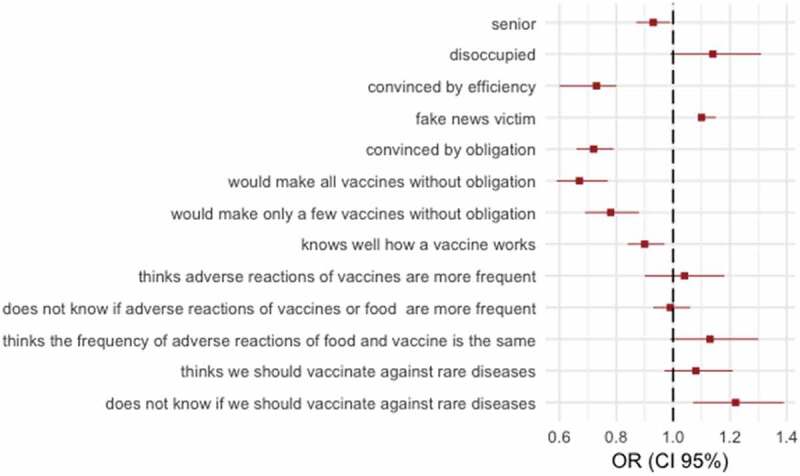

The multivariate logistic regression analysis made it possible to propose a final model with 9 variables adjusted for age greater than 60 years, profession, confidence in vaccine efficacy, having already received fake news on immunization, the opinion on requirements to vaccinate, the refusal to take some vaccines in the absence of obligation, the knowledge of how a vaccine works, the knowledge of the prevalence of the adverse effects of vaccines vs. food borne illness and lack of awareness of the value of vaccines for diseases that have become rare (Figure 1). In our model, people over the age of 60 were less hesitant (p = .03)

Figure 1.

Final multivariate model of characteristics associated with vaccine hesitancy among adults interviewed in 3 shopping centers in Italy, June-July 2019, n = 396

Confidence in the efficiency of vaccines and agreement with the vaccine requirement were decreased by 27% and 28%, respectively, for hesitants compared to non-hesitating individuals after adjustment for the other variables.

People who were victims of fake news were slightly more likely to hesitate with an odds ratio of 1.1 after adjusting for the other variables. Receiving all or only a few of the vaccines in the absence of obligation and knowledge of the way vaccines work was decreased by respectively 33%, 22% and 10% among people who are hesitant compared to non-hesitatant individuals after adjusting for the other variables in the model. Finally, the fact of not knowing whether or not to vaccinate against diseases that have become rare was also significantly associated with hesitation.

Discussion

Summary of the main results

Our study showed that 18% of respondents were hesitant about vaccines and a hesitant attitude seems not to have influenced the completion of the questionnaire. The proportion of hesitants did not vary according to the type of questionnaire. Multivariate analysis has shown that there is a greater hesitancy in poorly informed people including those who are unconvinced of vaccine efficacy, have been victims of fake news, do not know how vaccines work, and those who ignore the risk of not receiving vaccines including the importance of vaccination against diseases that have become rare. Likewise, people younger than 60 years old have greater hesitancy.

Generally, there was a large awareness of vaccine efficacy, safety and utility. Though a high proportion of people are in favor of vaccines, a considerable level of uncertainty persists toward vaccination: 25% of the people believed that vaccines are unsafe, and almost 50% of the hesitants and 15% of those favorable were still uncertain about vaccine safety. In addition, a large proportion of hesitants are doubtful about their efficacy. This shows the need to spread information about safety and effectiveness.

Even though our study did not reveal an overall difference in knowledge score between hesitants and favorable, there was a remarkable gap between them regarding the knowledge of the working mechanism of the vaccine.

Despite an insufficient level of knowledge about vaccines in 29.5% of the respondents, more than 50% of them would like to know more about vaccination revealing the openness to Public Health information on this topic. Only 13.9% knew the portal Vaccinarsì and less than 5% had visited it, with no difference between the hesitants or non hesitants, showing the need for more promotion of this information Website.

Analysis of literature data

Our study confirms the results of a 2018 Italian national study which did not include the Trentino-Alto Adige region15 and two surveys conducted in the south of Italy among kindergarten.19,20 In the national survey, 15% of adults were hesitant, a little lower rate than in our study. Actually, a higher level of hesitation in our study is consistent with lower coverage rates. The causes of hesitation mentioned were similar to ours: mainly safety issues related to vaccines and contradictory or negative opinions from health professionals. Although in our study the lack of perceived clarity of information was much greater among hesitants (84% vs. 44%), it was not associated with hesitation in the multivariate analysis.

People over 60 years of age were significantly less likely to hesitate in our study, possibly due to age-related long experience of no serious side effects following immunization, an understanding of the high risks of vaccine-preventable diseases due to personal memory or because of less exposure to fake news due to less internet and social network use. Another possible hypothesis is that they are no longer exposed to the vaccination obligation. The obligation applies to young children and therefore calls for the self-determination by their parents which are most frequently aged between 20 and 45 years old as shown in the two recent studies conducted in the south of Italy.19,20

However, one of the factors associated with hesitation in the population of our study was opposition to vaccination requirements. The reasons given were loss of self-determination (67%), “Big Pharma” conspiracy theory (44%) and the injustice of school exclusion. As shown in the report on vaccinations in Trentino in 2018,6 since the introduction of the immunization obligation in 2017, delays in vaccination have been reversed and coverage has been attained creating herd immunity (approximately 95% of 36-month-old children are up to date). Other studies have already shown a clear positive impact of the obligation for immunization coverage, however its impact on vaccine hesitancy is much more uncertain.21 Thus, the importance of accompanying these obligations with information on the collective benefits of vaccination and the concept of herd immunity.

However, opposition to obligation is not the only pitfall to vaccine confidence. In fact, 30% of the people surveyed in our study said they would not have received all the vaccines offered in the absence of obligation. Reasons given for non-vaccination included no obligation, fear of side effects, or lack of confidence in Western medicine. The determinants of hesitation are a mix of demographic, structural, social, and behavioral factors. In the multivariate analysis we have shown that a low level of information was associated with hesitation. In fact, the score of knowledge was low for 30% of the surveyed population; and there was a lack of correlation between the level of estimated knowledge and the actual level, with an overestimation of the level of knowledge in 37.4% of cases.

A low level of knowledge is the gateway for the influence of “scientific denialists”22 These use theories of conspiracy, false experts (Montanari in Italy), selectivity of references (Wakefied for autism), impossible expectations (100% of vaccines should have 0% side effects) and a false logic (syllogisms) to convince their listeners of inaccurate reasoning against vaccines.23

In addition, some studies have shown a link between a low level of education and vaccine hesitancy.24,25 Others, including one in the Veneto in 2011,26,27 showed the opposite. In the Italian national study and in our study no influence of sex or level of education was shown on vaccine hesitancy. In contrast, the lack of employment, which is often correlated with a lower level of education, was identified as possibly associated with hesitation in our study (p = .06). Another explanation is the link between populism and unemployment.28 The last years of Italian politics are characterized by the rise of populist parties shown by the victory of the coalition between the Five stars movement and the Liga in the election of 2018.

Several studies have shown a highly significant positive association between the proportion of people in a country who voted for populist parties and who believe that vaccines are not important.29,30

Vaccine education must therefore be carried out in all sections of the population regardless of sex and socio-cultural level. Indeed, given what is at stake in vaccine confidence and immunization programs, health officials and institutions – as well as NGOs and international agencies – should demonstrate utmost transparency, prudence, and accountability. This is necessary if they are to address the populist refrain of a corrupt establishment and if they are to restore the all-important element of trust that will doubtless continue to play a decisive role in the future of immunization. The advice of the health professionals and the guidelines of the health authorities are the sources of acceptance of the most cited vaccines.31–34 A huge initiative called Wellcome global monitor, the world’s largest study into how people around the world think and feel about science and major health challenges completed in 2018 showed that trust in vaccines tends to be strongly linked to trust in scientists and medical professionals; people who have strong trust in scientists overall are more trusting of vaccines, and vice versa.35 Another initiative called the vaccine confidence project aims at monitoring public confidence in immunization programs worldwide.36 They published a large survey of 28 European Union member states showing that Countries whose family Medical doctors are more confident in the importance, safety, and effectiveness of vaccines are more likely to have higher confidence among the public.4

In our study, over 75% of respondents said they inquired about vaccines with a doctor as in previous Italian studies.15,37 Hence the importance of educating health professionals regarding how to respond to anti-vax and hesitant claims.

However, we must not ignore the influence of the web38 and particularly social networks on the attitude of the population toward vaccines.14,23 The hesitants were much more likely to use social networks than those who are non-hesitating to find information about vaccines (57.5% vs. 25.5%) without being able to identify a causal link in the multivariate model adjusted on the other variables.

In our study, 41.4% of respondents were informed by official websites but only 14% were familiar with the VaccinarSì site; and less than 5% had already consulted it, which is similar to that of the Sicilian study in 2015 where only 6% of adults knew of the VaccinarSì site. The use of the VaccinarSì website by the general population should then be reinforced.

Perspectives

According to our study, several Public health interventions could probably be effective in this population of Trentino. In fact, education concerning how a vaccine works could certainly improve confidence about vaccines. Half of the population in our study would like to know more about vaccines and hesitants are more likely not to know how vaccines work. Discussing the obligation is another possible working path as many hesitants do not agree with the obligation. Hesitants are more likely to search for information on vaccines on social networks. This allows hesitant groups to form regardless of geography or politics as a result of web based brief messages, images and narratives.14,24 We should consider targeting this way of communication for scientific information.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has several strengths: the way of collecting data was inclusive. The shopping center recruitment allowed us a representative sample, as we interviewed people of all ages and from all social backgrounds. The proportion of hesitants and non hesitants did not vary according to the type of questionnaire. As a result, we are rather confident that the data collected through the long version of the questionnaire is representative of the entire study population. This is the first study of this kind in the region which gives originality to our work and quick spin-offs with suggested improvements to the layout of the website. A national study was done in 2016, but it did not include this region, which is the one with the lowest vaccination rate in the country.

Our study nevertheless had some biases. First, the chosen study design exposed us to a selection bias due to the settings chosen. Shopping centers could be less frequented by certain groups of people because of different consumption habits, reduced purchasing power or disabilities. In addition, due to location, we relied on self- definition of vaccine hesitancy, instead of the standard definition used in the literature (i.e. based on the respect of the immunization schedule) which may have selected another population. Moreover, we selected those who agreed to take the time to answer a questionnaire on vaccination, which might have excluded the most refractory ones. Also, our data might have been affected by an information bias, since self-administered questionnaires can include memory bias, recall bias, and social desirability bias. Nevertheless, we avoided as much as possible errors caused by misinterpretation providing the help of investigators if needed. We also avoided the omission or inaccuracy of a response by using an electronic case report which did not allow respondents to proceed if they failed to answer a question. We attempted to overcome confusion bias by performing a multivariate logistic regression model allowing an adjustment to the other explanatory variables. Unfortunately, we could not stratify on age or sex because of insufficient number of respondents.

Conclusion

Our survey measured a relatively high rate of vaccine hesitancy in the population of Trentino in 2019 (18%) and identified factors associated with hesitation including lack of knowledge, misinformation and being opposed to the obligation.

Our approach was well accepted by the surveyed population generating both interest and questions. Many of the people were grateful for this effort, which allowed them to increase their knowledge about vaccines and infectious diseases. They asked for information leaflets and the correct answers to the questions.

In order to counteract fake news about vaccinations it seems urgent to better inform the doctors but also the general population through developing innovative marketing and communication strategies. Given their undeniable spread and their growing influence on the beliefs of the population, some scientific profiles on social networks (Facebook, Instagram and Youtube) should be implemented, using interesting contents and redirecting to the official sites such as VaccinarSì. In a practical guide for the public to use in response to the anti-vax39 movement, the WHO in 2017 precisely explained the mechanisms behind the strong resistance of anti-vax or hesitants to scientific information. Indeed, several biases underlie misunderstanding: the bias of negativity (the audience trusts more negative information than positive and the credibility of the information than the reliability of the source), the bias of narration (the rational thinking of the audience is easily distorted by a narrative), the confirmation bias (the audience focuses on messages that confirm their perspective), and the Backfire effect (risk of creating a false belief by attempting to demystify it). These biases are mental shortcuts influencing individuals when making decisions in a complex world.40

It is essential to openly explain the reasons behind the vaccination obligation, to share proof of vaccine effectiveness, and dismantle the fake news regarding autism, fears regarding the immune system and the presence of heavy metals. This should be done by using short communications, more narratives of previous hesitants, and counter arguments to the anti-vax community. To support these innovative scientific communication strategies, it is necessary to carry out repeated media campaigns with the general population, such as during our survey in shopping centers; but also with healthcare professionals, in the schools, through newspapers, the internet and social networks.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

To the department of prevention of Trento and the University of Verona for supporting this work, to Luciane Murrone for designing the communication tools used for the survey. To Jim and Laury Young for their careful corrections.

Appendix.

| SHORT QUESTIONNAIRE | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/ ID CODE |___||___||___||___| |

2/ GENDER □ male □ female |

3/ AGE |___||___| |

4/ Do you know the website VaccinarSi? □ yes □ no |

||||

| 5/ What opinion do you have regarding vaccination? □ Positive □ Neutral □ Negative |

6/ If the vaccinations would not be mandatory would you receive them? □ yes, probably all □ yes, just some of them □ no |

7/ Do you agree with the mandatory vaccinations? □ yes (go to 8) □ no (go to 9) |

|||||

| 8/ If you agree is it because… (MCQ) □ it also protects the children who cannot get vaccinated □ it stops the diffusion of potentially serious diseases □ those scientific arguments are difficult to understand for parents so it’s better if scientists decide who needs to be vaccinated |

9/ If you don’t agree is it because it is not fare because…(MCQ) □ the diseases are rare so the vaccines are not needed □ others should not decide for my child □ it is not right to exclude a child from school |

10/ Do you agree to go further with the questionnaire? □ yes (go to 11) □ no (end of the questionnaire) |

|||||

| SOCIO-DEMOGRAFIC DATA | |||||||

| 11/ How many children under 15 do you have? □ 0 □ 1 □ 2 □ 3 □ more than 3 |

12/ How many children under 3 do you have? (MCQ) □ 0 □ 1 □ 2 □ I am pregnant |

13/ Where do you live? □ city center □ village □ countryside |

14/ In which province do you live? □ Bolzano □ Trento □ other |

||||

| 15/ What is your level of education? □ primary □ secondary □ bachelor □ Master/PhD |

16/ What is your profession? □ student □ retailer □ employee □ teacher □ artisan □ farmer □ manager |

□ artist □ free lance □ disoccupied □ housewife □ retired □ doctor □ health professional |

17/ Are you… □ in a relationship (married or cohabitee) □ single □ widowed |

18/ What is your country of origin? □ Italy □ other European □ in Africa □ in Asia □ in America □ in Oceania □ other |

|||

| SECTION 0 : ATTITUDES | |||||||

| 19/ Do you believe vaccines are : (MCQ) a. □ Effective □ not effective □ don’t know b. □ Secure □ unsecure □ I don’t know c. □ useful for me □ useful for the community □ not useful because the diseases are rare □ not useful because the community is clean □ I don’t know |

20/ Do/did you believe that vaccines: (MCQ) a. □ are without adverse effects □ have minor adverse effects □ have significant adverse effects B. □ can be responsible for autism □ contain quicksilver □ weaken the immune system □ none of the above answers □ I don’t know |

21/ If you ever chose not to accept the vaccine for you/your child, what was the reason? (MCQ) □ I have always accepted vaccination □ adverse effect of a previous vaccine □ medical contraindication □ the vaccine was not mandatory □ religious reason □ fear of side effects □ missing information □ I don’t trust in scientific medicine |

|||||

| SECTION 1: KNOWLEDGE ABOUT VACCINES | |||||||

| 22/ Do you know how does a vaccine work? □ very well □ well □ pretty well □ a little □ absolutely not |

23/ Would you like to know more? □ yes □ maybe □ no, I don’t need it □ no, I am not interested |

24/ Do you know what herd immunity means? □ yes □ maybe □ no |

|||||

| 25/ Do you think allergy is more frequent with vaccines or food? □ vaccines □ food □ same frequency □ I don’t know |

26/ Do you think it is useful to vaccinate for diseases no longer common? □ yes □ no □ I don’t know |

27/ Do you know why more than one vaccine is administered at the same time? □ yes □ maybe □ no |

|||||

| 28/ Do you think that too many vaccines are administered at the same time? □ yes (go to 29) □ no (go to 30) □ I don’t know (go to 30) |

29/ Why do you think that too many vaccines are administered at the same time? Because… (MCQ) □ I think there could be more side effects □ I don’t know (=information missing) □ I think it is too strong for the body □ babies are small and have immature immune systems □ it is an invention from the pharmaceutical industry to sell more vaccines |

||||||

| SECTION 2: KNOWLEDGE ABOUT DIEASES PREVENTABLE BY VACCINES | |||||||

| 30/ To prevent becoming infected by the diseases for which vaccines exist, what additional strategy would you adopt? (MCQ) | |||||||

| □ isolating the sick person □ wound desinfection □ physical activity □ washing hands □ organic diet |

□ antibiotics □ essential oils/ natural erbs □ homeopathy □ live in contact with the nature □ live in remote areas/ far from cities |

□ be infected by the disease □ I don’t know □ none of the answers |

|||||

| 31/ Do you recognize 2 symptoms/ complications of tetanus among the following? □ cough □ rash □ meningitis □ convulsion □ palsy □ death □ I don’t know |

32/ Do you recognize 2 symptoms/ complications of whooping cough among the following? □ cough □ rash □ meningitis □ convulsion □ palsy □ death □ I don’t know |

33/ Do you recognize 2 symptoms/ complications of measles among the following? □ cough □ rash □ meningitis □ convulsion □ palsy □ death □ I don’t know |

|||||

| 34/ Vaccines are available for which of the following diseases? □ diphteria □ tetanus □ poliomyelitis □ whooping cough □ pneumonia □ gastro-enteritis |

□ chickenpox □ hepatitis B □ hepatitis C □ measles □ mumps □ rubella |

□ tuberculosis □ meningitis □ papillomavirus □ influenza □ tick born encephalitis □ malaria |

|||||

| SECTION 3: MANDATORY VACCINES | |||||||

| 35/ Do you know which vaccines are recommended and which are mandatory? □ yes □ maybe □ no | |||||||

| SECTION 4: INFORMATION | |||||||

| 36/ Who do you usually get information about vaccines from? □ General practitioners □ pediatrician □ vaccination service □ school □ newspaper |

□ radio □ television □ internet □ friends/family |

||||||

| 37/ Do you think that the information received in the past were clear and sufficient? □ yes □ no □ contradictory information □ I don’t know | |||||||

| 38/ Have you received information about vaccines recently (in the past semester)? □ yes □ no □ I don’t remember | |||||||

| SECTION 5: INTERNET | |||||||

| 39/ Do you use internet to access information about vaccines? □ yes (go to 40) □ no (end of the questionnaire) | |||||||

| 40/ If yes, how? □ official sites (ministry, state, vaccination services) □ newspaper websites □ blog |

□ twitter □ Youtube □ other |

||||||

| 41/ Have you ever visited the website VaccinarSi? □ yes (go to 42) □ no (end of the questionnaire) |

42/ Did you find it useful? □ yes (end of the questionnaire) □ no (go to 43) |

||||||

| 43/ Why didn’t you find it useful? □ I didn’t like the design □ too much information □ the language is too complicated □ other | |||||||

Funding Statement

The societa' italiana di igiene medicina preventiva e sanita' pubblica financed 1000 euros for communication tools.

Ethics and consent to participate

All participants gave their oral consent to participate and could retract at any time. All the data was completely anonymous. The directors of the shopping centers signed a participation agreement in accordance with the requirements of the Trento Bioethics Committee. SurveyMonkey, the survey program, is certified by the two Privacy Shield EU-US and Swiss-US programs (privacyshield.gov) that provide a legal framework for the collection, exploitation, transfer and analysis of data.

Consent for publication

All the participants gave their consent for publication of the data.

Authors’ contributions

BM, SM, MZ and AG contributed to the conceptualization and methodology. BM, PB, CB, VT collected the data. BM investigated, analyzed the data and wrote the original draft. PB, AF, AG and SM reviewed and edited the data.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Availability of data and materials

All data is accessible by request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1763085.

References

- 1.Plotkin S. History of vaccination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:12283–87. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400472111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dubé E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J.. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2013;9:1763–73. doi: 10.4161/hv.24657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larson HJ, de Figueiredo A, Xiahong Z, Schulz WS, Verger P, Johnston IG, Cook AR, Jones NS. The State of Vaccine Confidence 2016: global Insights Through a 67-Country Survey. EBioMedicine. 2016;12:295–301. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.2018_vaccine_confidence_en.pdf [Internet]. [accessed 2020. February 27]. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/vaccination/docs/2018_vaccine_confidence_en.pdf.

- 5.Filia A, Bella A, Del Manso M, Baggieri M, Magurano F, Rota MC. Ongoing outbreak with well over 4,000 measles cases in Italy from January to end August 2017 - what is making elimination so difficult? Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2017;22:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Copertura vaccinale in Italia [Internet]. [accessed 2019. September 12]. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/vaccini/dati_Ita.

- 7.Siani A. Measles outbreaks in Italy: A paradigm of the re-emergence of vaccine-preventable diseases in developed countries. Prev Med. 2019;121:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.senato.it - La Costituzione - Articolo 114 [Internet]. [accessed 2019. October 3]. https://www.senato.it/1025?articolo_numero_articolo=114&sezione=136.

- 9.Signorelli C. Forty years (1978–2018) of vaccination policies in Italy. Acta Bio-Medica Atenei Parm. 2019;90:127–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crenna S, Osculati A, Visonà SD. Vaccination policy in Italy: an update. J Public Health Res. 2018;7:1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf [Internet]. [accessed 2019. June 18]. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf.

- 12.WHO | global Vaccine Action Plan 2011–2020 [Internet]. WHO [accessed 2019. May 21]. http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/.

- 13.Ferro A, Bonanni P, Castiglia P, Montante A, Colucci M, Miotto S, Siddu A, Murrone L, Baldo V. Improving vaccination social marketing by monitoring the web. Ann Ig Med Prev E Comunita. 2014;26:54–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonanni P, Ferro A, Guerra R, Iannazzo S, Odone A, Pompa MG, Rizzuto E, Signorelli C. Vaccine coverage in Italy and assessment of the 2012–2014 National Immunization Prevention Plan. Epidemiol Prev. 2015;39:146–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giambi C, Fabiani M, D’Ancona F, Ferrara L, Fiacchini D, Gallo T, Martinelli D, Pascucci MG, Prato R, Filia A, et al. Parental vaccine hesitancy in Italy – results from a national survey. Vaccine. 2018;36:779–87. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larson HJ, Jarrett C, Schulz WS, Chaudhuri M, Zhou Y, Dube E, Schuster M, MacDonald NE, Wilson R. SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy. Measuring vaccine hesitancy: the development of a survey tool. Vaccine. 2015;33:4165–75. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bouletreau A, Chouaniere D, Wild P, Fontana JM. Concevoir, traduire et valider un questionnaire. A propos d’un exemple, EUROQUEST, 50.

- 18.Report of the sage working group on vaccine hesitancy . WHO [Internet]; 2014. [accessed 2020 March5]. https://www.who.int/immunization/sage/meetings/2014/october/SAGE_working_group_revised_report_vaccine_hesitancy.pdf?ua=1.

- 19.Napolitano F, D’Alessandro A, Angelillo IF. Investigating Italian parents’ vaccine hesitancy: A cross-sectional survey. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14:1558–65. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1463943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bianco A, Mascaro V, Zucco R, Pavia M. Parent perspectives on childhood vaccination: how to deal with vaccine hesitancy and refusal? Vaccine. 2019;37:984–90. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.12.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Partouche H, Gilberg S, Renard V, Saint-Lary O. Mandatory vaccination of infants in France: is that the way forward? Eur J Gen Pract. 2019;25:49–54. doi: 10.1080/13814788.2018.1561849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grignolio A. Vaccines: are they Worth a Shot? Switzerland: Springer; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diethelm P, McKee M. Denialism: what is it and how should scientists respond? Eur J Public Health. 2009;19:2–4. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckn139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown AL, Sperandio M, Turssi CP, Leite RMA, Berton VF, Succi RM, Larson H, Napimoga MH. Vaccine confidence and hesitancy in Brazil. Cad Saude Publica. 2018;34:e00011618. doi: 10.1590/0102-311x00011618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomson A, Robinson K, Vallée-Tourangeau G. The 5As: A practical taxonomy for the determinants of vaccine uptake. Vaccine. 2016;34:1018–24. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.11.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salmon DA, Moulton LH, Omer SB, deHart MP, Stokley S, Halsey NA. Factors associated with refusal of childhood vaccines among parents of school-aged children: a case-control study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:470–76. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.5.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CENSIS, Cultura della vaccinazione in Italia: un’indagine sui genitori, october 2014 [Internet]. [accessed 2019. December 9]. http://www.quotidianosanita.it/allegati/allegato6485077.pdf.

- 28.Passari E. The great recession and the rise of populism. Intereconomics. 2020;55:17–21. doi: 10.1007/s10272-020-0863-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy J. Populist politics and vaccine hesitancy in Western Europe: an analysis of national-level data. Eur J Public Health. 2019;29:512–16. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckz004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lasco G, Larson HJ. Medical populism and immunisation programmes: illustrative examples and consequences for public health. Glob Public Health. 2020;15:334–44. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1680724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yaqub O, Castle-Clarke S, Sevdalis N, Chataway J. Attitudes to vaccination: a critical review. Soc Sci Med. 2014;112:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ragan KR, Bednarczyk RA, Butler SM, Omer SB. Missed opportunities for catch-up human papillomavirus vaccination among university undergraduates: identifying health decision-making behaviors and uptake barriers. Vaccine. 2018;36:331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.D’Alessandro A, Napolitano F, D’Ambrosio A, Angelillo IF. Vaccination knowledge and acceptability among pregnant women in Italy. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2018;14:1573–79. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2018.1483809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Napolitano F, Napolitano P, Liguori G, Angelillo IF. Human papillomavirus infection and vaccination: knowledge and attitudes among young males in Italy. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2016;12:1504–10. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2016.1156271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wellcome Global Monitor 2018 . Wellcome [Internet]. [accessed 2020. March 6]. https://wellcome.ac.uk/reports/wellcome-global-monitor/2018.

- 36.The Vaccine Confidence Project [Internet]. Vaccine confidence Project. [accessed 2020. March 6]. https://www.vaccineconfidence.org.

- 37.Tabacchi G, Costantino C, Cracchiolo M, Ferro A, Marchese V, Napoli G, Palmeri S, Raia D, Restivo V, Siddu A, et al. Information sources and knowledge on vaccination in a population from southern Italy: the ESCULAPIO project. Hum Vaccines Immunother. 2017;13:339–45. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1264733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Betsch C, Renkewitz F, Betsch T, Ulshöfer C. The influence of vaccine-critical websites on perceiving vaccination risks. J Health Psychol. 2010;15:446–55. doi: 10.1177/1359105309353647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Best-practice-guidance-respond-vocal-vaccine-deniers-public.pdf [Internet]. [accessed 2019. September 12]. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/315761/Best-practice-guidance-respond-vocal-vaccine-deniers-public.pdf.

- 40.Tversky A, Kahneman D. Judgment under uncertainty: Heuristics and biases. Science. 1974;185:10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- 2018_vaccine_confidence_en.pdf [Internet]. [accessed 2020. February 27]. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/vaccination/docs/2018_vaccine_confidence_en.pdf.

- Copertura vaccinale in Italia [Internet]. [accessed 2019. September 12]. https://www.epicentro.iss.it/vaccini/dati_Ita.

- senato.it - La Costituzione - Articolo 114 [Internet]. [accessed 2019. October 3]. https://www.senato.it/1025?articolo_numero_articolo=114&sezione=136.

- C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf [Internet]. [accessed 2019. June 18]. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_2571_allegato.pdf.

- WHO | global Vaccine Action Plan 2011–2020 [Internet]. WHO [accessed 2019. May 21]. http://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/GVAP_doc_2011_2020/en/.

- CENSIS, Cultura della vaccinazione in Italia: un’indagine sui genitori, october 2014 [Internet]. [accessed 2019. December 9]. http://www.quotidianosanita.it/allegati/allegato6485077.pdf.

- Wellcome Global Monitor 2018 . Wellcome [Internet]. [accessed 2020. March 6]. https://wellcome.ac.uk/reports/wellcome-global-monitor/2018.

- The Vaccine Confidence Project [Internet]. Vaccine confidence Project. [accessed 2020. March 6]. https://www.vaccineconfidence.org.

- Best-practice-guidance-respond-vocal-vaccine-deniers-public.pdf [Internet]. [accessed 2019. September 12]. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/315761/Best-practice-guidance-respond-vocal-vaccine-deniers-public.pdf.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data is accessible by request.