Abstract

Ethnic group discrimination represents a notable risk factor that may contribute to mental health problems among ethnic minority college students. However, cultural resources (e.g., ethnic identity) may promote psychological adjustment in the context of group-based discriminatory experiences. In the current study, we examined the associations between perceptions of ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms, and explored dimensions of ethnic identity (i.e., exploration, resolution, and affirmation) as mediators of this process among 2,315 ethnic minority college students (age 18 to 30 years; 37% Black, 63% Latino). Results indicated that perceived ethnic group discrimination was associated positively with depressive symptoms among students from both ethnic groups. The relationship between perceived ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms was mediated by ethnic identity affirmation for Latino students, but not for Black students. Ethnic identity resolution was negatively and indirectly associated with depressive symptoms through ethnic identity affirmation for both Black and Latino students. Implications for promoting ethnic minority college students’ mental health and directions for future research are discussed.

Keywords: depressive symptoms, emerging adults, ethnic identity, perceived ethnic group discrimination, rejection-identification

The college environment provides young adults with opportunities to engage in identity exploration beyond what is generally available in adolescence, as well as to interact with ethnically diverse peers in an academically focused environment (Arnett & Tanner, 2006). Some students encounter more diversity in the college environment than in their high schools and neighborhoods (e.g., Locks, Hurtado, Bowman, & Oseguera, 2008), and these experiences are likely to promote ethnic identity development (Phinney & Alipuria, 1990; V. Torres, 2003). For ethnic minority college students (e.g., Black and Latino), this new environment can also increase exposure to perceived discrimination (based on ethnic group membership) through interactions with diverse peers and instructors, and these occurrences can impact mental health negatively (Harris-Britt, Valrie, Kurtz-Costes, & Rowley, 2007; Williams & Mohammed, 2009). However, perceived discrimination does not always directly lead to negative outcomes among ethnic minority individuals (e.g., Armenta & Hunt, 2009; Berkel et al., 2010; Branscombe, Schmitt, & Harvey, 1999). Thus, it is important to investigate the mechanisms that underlie the associations between perceived ethnic discrimination and mental health problems in order to understand how resilience transpires.

In the current study, we examined the association between perceptions of ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms. Equally important, ethnic identity was examined as a potential risk-reducing factor for depressive symptoms in the context of ethnic group discrimination (Branscombe et al., 1999). Unlike previous studies assessing ethnic identity as a singular construct (e.g., Donovan et al., 2013), we examined multiple dimensions of ethnic identity, including exploration, resolution, and affirmation (e.g., Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gómez, 2004). Finally, because U.S. ethnic groups have varied histories in the country, we explored whether patterns of associations varied between two groups, specifically, Black and Latino college students.

Perceived Ethnic Discrimination and Mental Health Problems

Discrimination comes in many forms, including differential treatment based on gender, race and ethnicity, and sexual orientation (Pincus, 2000). In this article, we focus specifically on discrimination related to ethnic group membership. Several studies have investigated how perceived ethnic and racial discrimination may affect mental health (Noh & Kaspar, 2003; Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams, Neighbors, & Jackson, 2003). For example, research by Mendoza-Denton, Purdie, Downey, and Davis (2002) indicated that rejection sensitivity (anticipation of discrimination based on minority status) can have deleterious effects on ethnic minority students’ well-being. Studies show that perceptions of ethnic discrimination are associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms among both Black and Latino individuals (e.g., Hall, Cassidy, & Stevenson, 2008; Moradi & Risco, 2006; Pieterse, Todd, Neville, & Carter, 2012). Among African American young adults, Sellers, Caldwell, Schmeelk-Cone, and Zimmerman (2003) observed that perceived racial discrimination was associated with higher levels of depressive symptoms. Similarly, using a daily diary method, L. Torres and Ong (2010) found that perceived ethnic discrimination was related positively to depressive symptoms among Latino adults.

Although several studies have examined ethnic discrimination generally, research further indicates that ethnic discrimination comes in the form of interpersonal (individual) and group experiences (e.g., Pincus, 2000; Taylor, Wright, Moghaddam, & Lalonde, 1990). Prior literature has mostly focused on implications of interpersonal (individual) ethnic discriminatory experiences for mental health (reviewed by Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Smart Richman & Leary, 2009), whereas far less is known about the impact of perceived ethnic group discrimination (i.e., denigration of one’s group as a whole). Extant research does indicate that, over and above direct interpersonal experiences of discrimination, perceptions of institutional barriers related to race and ethnicity may pose significant risks for mental health problems (e.g., Karlsen & Nazroo, 2002). A few studies have found that although interpersonal ethnic discrimination negatively affects self-esteem, perceived ethnic group discrimination is sometimes associated with higher self-esteem (e.g., Armenta & Hunt, 2009; Bourguignon, Seron, Yzerbyt, & Herman, 2006), which may serve as an indicator of mental health. Given the lack of clarity regarding the impact of ethnic group discrimination on mental health, we focus on discrimination related to ethnic group membership as opposed to interpersonal discriminatory experiences.

In the current study, we examined ethnic minority college students’ perceptions of ethnic group discrimination, operationalized as a composite of one’s beliefs regarding societal attitudes about one’s ethnic group as a whole (often described as public regard; Sellers, Smith, Shelton, Rowley, & Chavous, 1998) and perceptions of institutional barriers based on ethnicity. As suggested by Karlsen and Nazroo (2002), it is possible that perceptions that one’s group has limited access to resources related to minority status may represent a type of social stress that is directly associated with increased depressive symptoms among Black and Latino college students. Conversely, perceived ethnic group discrimination may indirectly relate to depressive symptoms through cultural factors, such as ethnic identity, which are associated negatively with depressive symptoms.

The Rejection-Identification Model: The Mediating Role of Ethnic Identity

Theories of risk and resilience highlight the importance of cultural factors that can mitigate the influence of risk processes on mental health challenges (Roosa, Wolchik, & Sandler, 1997). There are several ways that cultural factors, such as ethnic identity, can influence the associations between perceived ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms. Although some researchers have examined the buffering role of ethnic identity (e.g., L. Torres, Yznaga, & Moore, 2011), other scholars assert that ethnic identity also can lessen the impact of risk by mediating the associations between risk factors and depressive symptoms (e.g., Donovan et al., 2013). Roosa et al. (1997) referred to such mediating cultural factors as “risk reducers.” Furthermore, it is possible that some risk factors, such as ethnic discrimination, actually impact cultural characteristics as well. For example, there is evidence that experiencing discrimination triggers stronger ethnic group identification and affiliation, which may then promote psychological adjustment among African American and Latino young adults (Armenta & Hunt, 2009; Branscombe et al., 1999). Branscombe et al. (1999) referred to this mediating phenomenon as the “rejection-identification” effect.

Branscombe et al. (1999) argued that perceptions of ethnic discrimination may motivate individuals to become more strongly identified with their ethnic group, which can compensate for the negative psychological consequences of perceived ethnic group discrimination (see also Cross, 1995; Phinney, 1993). In an initial test of the rejection-identification effect, general perceptions of ethnic discrimination, as well as tendencies to attribute negative experiences to discrimination, were positively associated with ethnic identification (affiliation with one’s ethnic group) among African American adults (Branscombe et al., 1999). Furthermore, ethnic identification was associated positively with favorable psychological and psychosocial outcomes (i.e., higher self-esteem and fewer negative emotions). Importantly, Armenta and Hunt (2009) replicated these findings with a sample of Latino adolescents. In both Branscombe et al.’s and Armenta and Hunt’s studies, perceived ethnic discrimination had a significant indirect positive relationship with favorable psychological outcomes through ethnic identification, suggesting a compensating, or mediating, role that ethnic identity may serve between perceived ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms. However, one limitation was that these studies did not differentiate interpersonal experiences from perceptions of group discrimination.

Using a sample of participants from the larger study from which data for the present study were taken, Donovan et al. (2013) did not find that an overall sense of ethnic identity mediated the associations between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms in a culturally diverse sample of college students that included Black and Latino individuals. However, Donovan et al.’s study also did not differentiate between interpersonal and group experiences of discrimination. Moreover, they did not examine ethnic identity as a multidimensional construct. Therefore, the extent to which specific dimensions of ethnic identity serves a mediating role between perceived ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms remains unclear.

The Multidimensionality of Ethnic Identity

Ethnic identity, one aspect of an individual’s overall identity, stems from the sense of belonging that individuals gain from ethnic group affiliation, and is defined by cultural heritage and attributes, such as values, traditions, and language (Cokley, 2007; Phinney & Ong, 2007; Quintana, 2007). It includes aspects of one’s identity that are derived from ethnic identification (e.g., identifying with an ethnic category) and ethnic group membership (e.g., Ashmore, Deaux, & McLaughlin-Volpe, 2004; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). Although ethnic identity is best conceptualized as multidimensional, different aspects are rarely investigated in the same study (e.g., Brittian, Umaña-Taylor, & Derlan, 2013a; Rivas-Drake, Hughes, & Way, 2009; Rowley, Sellers, Chavous, & Smith, 1998). Further, various dimensions of ethnic identity may be differentially related to ethnic minority individuals’ perceptions of discrimination (e.g., Syed & Azmitia, 2008) and mental health problems (Brittian et al., 2013a; Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006).

Ethnic Identity Exploration

Ethnic identity exploration (e.g., learning about one’s ethnic group) and ethnic identity resolution (e.g., resolving the identity task) are components of a developmental process through which individuals form an ethnic identity, which often gives rise to ethnic identity achievement (e.g., Phinney & Ong, 2007; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). Several studies have reported that exploration and resolution are highly intercorrelated, but distinct, dimensions of ethnic identity achievement (e.g., Phinney & Ong, 2007; Toomey, Umaña-Taylor, Updegraff, & Jahromi, 2013; Umaña-Taylor, O’Donnell, et al., 2014). Studies involving ethnic identity exploration have found both positive and negative relationships with adjustment (primarily psychosocial well-being; e.g., Romero & Roberts, 2003; Umaña-Taylor, Gonzales-Backen, & Guimond, 2009; Umaña-Taylor & Shin, 2007; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004) and internalizing symptoms (e.g., Schwartz, Zamboanga, Weisskirch, & Rodriguez, 2009) among adolescents. In turn, research indicates that perceived discrimination is positively related to ethnic identity exploration (Pahl & Way, 2006; Phinney, 1992; Romero & Roberts, 1998), and studies show that ethnic identity exploration is positively related to self-esteem (e.g., Romero & Roberts, 2003; Umaña-Taylor & Shin, 2007; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004). Schwartz et al. (2009) found that ethnic identity exploration was weakly associated with internalizing symptoms (e.g., anxiety and depression) through identity confusion in a sample involving White, Black, and Hispanic college students. However, among biethnic college students, Brittian et al. (2013a) found no such relationships between ethnic identity exploration and mental health problems (specifically anxiety and depressive symptoms). Thus, although perceived ethnic discrimination may be positively related to students’ ethnic identity exploration, and ethnic identity exploration may be positively (higher self-esteem) or negatively (increased internalizing symptoms) related to adjustment, it is unclear whether this dimension of ethnic identity mediates the association between ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms.

Ethnic Identity Resolution

Although ethnic identity exploration is a developmentally appropriate experience for younger adolescents, and may represent the primary mechanism through which ethnic identity develops (Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, et al., 2014), ethnic identity resolution (clarity and commitment regarding one’s ethnic group membership) may be a particularly critical component of ethnic identity development for college-age youth. Erikson (1968) proposed that resolution of the identity task in late adolescence and early adulthood is necessary for healthy adult development and adaptive psychological functioning. Ethnic identity resolution may represent a critical dimension of young adults’ ethnic identity, especially with regard to handling discrimination, because individuals who fail to develop a coherent sense of self are more likely to experience higher levels of anxiety (Côté, 2009). Individuals who have a clear sense of their ethnic group membership (resolution) are less sensitive to opposition and threats to the self (e.g., Côté, 2009; Phinney & Kohatsu, 1997; Phinney & Ong, 2007). Furthermore, it is also possible that perceived ethnic group discrimination may strengthen one’s ethnic group commitment, as indicated by the rejection-identification model (Branscombe et al., 1999). In this case, perceived ethnic group discrimination would lead to stronger ingroup identification, which then protects mental health (Armenta & Hunt, 2009; Romero & Roberts, 2003). Alternatively, perceived ethnic group discrimination might reduce clarity (e.g., resolution) about one’s ethnic group membership. For example, encountering discriminatory experiences related to ethnicity may cause confusion about what ethnic group membership means to the individual (e.g., Umaña-Taylor, Vargas-Chanes, Garcia, & Gonzales-Backen, 2008). Therefore, it is also possible that perceived ethnic group discrimination is related to depressive symptoms among ethnic minority college students through its direct relationship with ethnic identity resolution.

Ethnic Identity Affirmation

The affective component of ethnic identity, ethnic identity affirmation (also described as ethnic pride in the literature), is particularly important for ethnic minority individuals (Phinney & Ong, 2007; Rivas-Drake, Syed, et al., 2014). Furthermore, ethnic identity affirmation may represent one product (or type of content) of ethnic identity achievement (e.g., exploring and resolving the identity task around ethnicity; Phinney & Ong, 2007; Sellers et al., 1998). Research indicates that ethnic identity affirmation is directly associated with fewer depressive symptoms among African American and Latino youth (e.g., Brittian et al., 2013b; Gaylord-Harden, Ragsdale, Mandara, Richards, & Petersen, 2007). Moreover, ethnic identity affirmation may also play a critical role in the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health problems (Knight, Cota, & Bernal, 1993; Phinney & Ong, 2007; Sellers, Copeland-Linder, Martin, & Lewis 2006). Therefore, studies generally indicate that ethnic identity affirmation serves an important role in promoting mental health among ethnic minorities.

Although scholars assert that ethnic identity affirmation is particularly important for ethnic minority individuals who experience ethnic group discrimination (Phinney & Ong, 2007), the direction of this association is not clear. For example, studies show that perceptions that one’s group is treated unfairly in society are related to higher ethnic identity affirmation among some individuals (e.g., Major & O’Brien, 2005), but to lower ethnic identity affirmation among other individuals (e.g., Rivas-Drake et al., 2009; Romero & Roberts, 2003). In addition, developmental theory indicates that attaining ethnic identity resolution can facilitate or serve as a conduit to ethnic identity achievement, and, in turn, positive feelings (affirmation) about one’s ethnic group membership are likely to ensue (Phinney & Ong, 2007). Therefore, it is also possible that ethnic identity affirmation serves as a mechanism through which resolution of one’s ethnic identity leads to fewer depressive symptoms.

Variability by Ethnic Group

The situational and phenomenological experiences of ethnic group discrimination may vary between and among Black and Latino individuals in the United States. For Black Americans (a group that is comprised primarily of African Americans, with a growing number of immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean), the history of discrimination has included laws and policies that prevented economic and educational equity (e.g., discriminatory housing practices and “separate but equal” edicts), laws that defined African Americans as property, and a history of enslavement that led to a loss of indigenous cultural values and practices (Sellers et al., 1998). Given these experiences, it is likely that many Black American students think of themselves in terms of race rather than ethnicity, and it is similarly possible that they attribute discriminatory experiences to racial group membership rather than to ethnicity (e.g., discrimination based on language or cultural practices). However, others have argued that race and ethnicity may be inseparable for African Americans because of their history in the United States (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2014). Furthermore, despite the fact that many Black individuals identify racially, scholars have asserted that ethnic identity can be assessed among Black Americans (Rivas-Drake, Seaton, et al., 2014).

In comparison, among Latinos, the relatively recent history of immigration, rather than enslavement, contributes to a historical context that varies from the experiences of Black Americans (e.g., Crenshaw, Gotanda, Peller, & Thomas, 1995). Many Latino students have family members that reside in their country of origin, can readily identify a specific country of origin, and can describe cultural practices that define their ethnic group (e.g., Phinney, 1996). A recent study by the Pew Research Center indicated that the majority of Latino individuals in the United States preferred to define themselves by their family’s country of origin rather than using a panethnic label (e.g., “Latino”; Taylor, Hugo Lopez, Hamar Martinez, & Velasco, 2012). Therefore, it is likely that Latino college students may attribute prejudice and discrimination to language and immigration issues, rather than to a specific racial or ethnic minority group status (Edwards & Romero, 2008). For these reasons, we examined variability between Black and Latino students in the current study.

The Current Study

In sum, we expected that perceived ethnic group discrimination would be positively associated with depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that perceived ethnic group discrimination would be positively associated with ethnic identity exploration, but that ethnic identity exploration would not be associated with depressive symptoms (following Brittian et al., 2013a). Given our focus on college students (ages 18 to 30 years), who were likely beyond the formative stages of ethnic identity formation (French, Seidman, Allen, & Aber, 2006), we did not anticipate findings for ethnic identity exploration. Rather, we expected that perceived ethnic group discrimination would be associated with higher ethnic identity resolution, and we predicted that higher ethnic identity resolution would, in turn, be associated with fewer depressive symptoms. We hypothesized that perceived ethnic group discrimination would be associated with lower ethnic identity affirmation (less positive feelings about being a member of a stigmatized group), but that higher ethnic identity affirmation would be associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Based on developmental theory and research, we hypothesized that resolution (a process dimension) would be a particularly important aspect of ethnic identity development for ethnic minority young adults’ mental health and would relate to fewer depressive symptoms through its relationship with ethnic identity affirmation (a content dimension). Finally, we explored variations in patterns of association by ethnicity.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited from 30 colleges and universities across the United States as part of the Multi-Site University Study of Identity and Culture (for more details, see Castillo & Schwartz, 2013; Weisskirch et al., 2013). The current study included 2,315 college students (63% Latino, 37% Black; 76% female). Participants self-identified their ethnic group by responding to a forced-choice ethnic question—“Which ethnic group do you belong to?”—with answer choices being Black/African American, Caucasian/White, Asian/Pacific Islander, Latino/Hispanic, Middle Eastern/Arab, and Colored-South African/Cape Malay. Those who did not self-identify their ethnicity as being Latino or Black were excluded from analyses. As such, perceived ethnic group discrimination and ethnic identity measures were responded to in reference to their self-selected ethnic group membership.

On average, participants were 20.02 years old (SD = 2.13, range = 18 to 30) and most were U.S. born (80%). Among Black students, 85% were born in the United States (predominately African American and Caribbean Black) and 15% were born outside of the United States (3% Haiti; 3% Jamaica; 1% Nigeria; 8% other Caribbean, African, and European countries). Among Latino students, 79% were born in the United States (predominantly Mexican American and Cuban American) and 21% were born outside of the United States (5% Cuba; 3% Colombia; 3% Mexico; 2% Venezuela; and 8% other Central American, South American, and European countries).

Data were collected via an online survey completed by students attending one of the 30 participating universities between September 2008 and October 2009. Each participating university’s institutional review board approved the study. Participating universities represented small to large, as well as public and private, universities. The online survey took approximately 90 min to complete. Of the students who started the questionnaire, 73% completed the entire survey.

Measures

Perceived ethnic group discrimination.

Perceived ethnic group discrimination was assessed using seven items from the perceived discrimination subscale of the Scale of Ethnic Experience (SEE; Malcarne, Chavira, Fernandez, & Liu, 2006). Items assessed participants’ perceptions of public regard (e.g., perceptions of criticism of and respect for one’s ethnic group) and treatment of their ethnic group in America (e.g., perceived barriers to opportunity). Sample items included “My ethnic group is often criticized in this country,” “My ethnic group does not have the same opportunities as other ethnic groups,” and “Generally speaking, my ethnic group is respected in America (reverse coded).” Participants rated each item on a scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The SEE has previously been used with Latino and Black college students (e.g., Cooper, Mills, Bardwell, Ziegler, & Dimsdale, 2009; Malcarne et al., 2006; Malcarne, Fernandez, & Flores, 2005). In the current study, Cronbach’s alphas were .75 for Blacks and .82 for Latinos.

Ethnic identity.

Ethnic identity was measured using the 17-item Ethnic Identity Scale (Umaña-Taylor et al., 2004), which assesses three dimensions of ethnic identity: exploration, resolution, and affirmation. Sample items include “I have attended events that have helped me learn more about my ethnicity” (exploration), “I am clear about what my ethnicity means to me” (resolution), and “I wish I were a different ethnicity” (affirmation, reverse scored). Participants rated each item on a scale ranging from 1 = does not describe me at all to 4 = describes me very well. Cronbach’s alphas across the three scales ranged from .83 to .89 for Blacks, and from .85 to .90 for Latinos.

Depressive symptoms.

Depressive symptoms were measured using a modified version of the 20-item Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). On the original CES-D, participants indicate the degree to which they had experienced symptoms associated with major depression (e.g., “I felt lonely”) during the previous week on a 4-point scale, anchored by 0 (rarely or none of the time; less than one day) to 3 (most or all of the time; 5–7 days). To remain consistent with the response options used throughout the larger survey, participants rated each item on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In the current study, alpha coefficients were .86 for Blacks and .87 for Latinos.

Analytic Plan

Analyses were conducted using path analysis in Mplus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010) and missing data were handled using full information maximum likelihood (Enders, 2010). Gender and nativity were included as controls. Consistent with Bollen’s (1989) Multiple Indicators Multiple Causes method, we included paths from these control variables to all exogenous (i.e., perceived ethnic group discrimination) and endogenous (i.e., exploration, resolution, affirmation, and depressive symptoms) variables.

To test our hypothesized model, direct paths were included from perceived ethnic group discrimination to depressive symptoms, from perceived ethnic group discrimination to the three dimensions of ethnic identity, and from the three dimensions of ethnic identity to depressive symptoms. Model fit was evaluated based on multiple fit indices. Good (acceptable) model fit is reflected by Comparative Fit Index (CFI) values of .95 (.90) or higher (Hoyle, 1995; Kline, 2005; Ullman, 1996), root mean square error approximation (RMSEA) values less than .05 (.08), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) values less than .05 (.08; Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005).

Once a final model was identified, we used multiple-group invariance analyses to test whether the model parameters differed significantly across Black and Latino students. Tests for moderation involved a number of steps: (a) an initial configural invariance model was tested, allowing all estimated paths to vary across the two ethnic groups (i.e., fully free model); (b) a metric invariance model was estimated to test for invariance in the estimated paths by constraining the paths to be equal across groups; (c) competing models were compared using the chi-square difference test; and (d) the configural model was compared with the metric model using the χ2 difference test to determine whether there were significant differences between the two groups, and follow-up tests (if needed) were conducted to identify paths that needed to be freely estimated across groups. We examined the modification indices to identify paths that needed to be freed. As there are no widely accepted alternatives to the chi-square change Δχ2) test for comparing the fit of alternative models (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), especially when focusing on structural relationships (Little, Card, Slegers, & Ledford, 2007), we used only the Δχ2 test to compare the fit of nested models. In cases in which the Δχ2 test was significant, RMSEA and SRMR values were examined as additional indicators of model fit. Lower RMSEA and SRMR values indicate better fit, with scores closer to zero indicating perfect fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

After identifying the final model, mediation was tested following the recommendations of MacKinnon, Lockwood, and Williams (2004). Specifically, the bias-corrected empirical bootstrap method with confidence intervals was utilized and is described in further detail in the Results section.

Results

Preliminary analyses indicated that Black students reported higher levels of perceived ethnic group discrimination and ethnic identity exploration compared with Latino students (see Table 1 for descriptive statistics). On average, Latino students reported higher levels of ethnic identity affirmation compared with Black students. Female students, relative to males, reported higher levels of perceived ethnic group discrimination, ethnic identity exploration, ethnic identity resolution, and ethnic identity affirmation. U.S.-born students reported higher perceptions of ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms compared with foreign-born students; in contrast, foreign-born students reported higher levels of ethnic identity exploration and ethnic identity resolution compared with U.S.-born students. Zero-order correlations among study variables appear in Table 2.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Key Study Variables by Demographic Characteristics

| Black | Latino | Male | Female | U.S. born | Foreign born | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| PEGD | 3.35 | 0.75 | 3.02 | 0.82 | 3.02 | 0.73 | 3.17 | 0.83 | 3.17 | 0.80 | 2.99 | 0.84 |

| Exploration | 2.86 | 0.74 | 2.69 | 0.75 | 2.65 | 0.74 | 2.78 | 0.75 | 2.73 | 0.75 | 2.83 | 0.75 |

| Resolution | 2.96 | 0.84 | 2.96 | 0.81 | 2.88 | 0.81 | 2.98 | 0.82 | 2.92 | 0.82 | 3.06 | 0.83 |

| Affirmation | 3.64 | 0.54 | 3.72 | 0.50 | 3.55 | 0.61 | 3.74 | 0.47 | 3.69 | 0.52 | 3.71 | 0.50 |

| Depressive symptoms | 2.59 | 0.73 | 2.53 | 0.77 | 2.55 | 0.76 | 2.56 | 0.75 | 2.57 | 0.75 | 2.48 | 0.75 |

Note. Bolded means within the same row differ significantly at p < .05. PEGD = perceived ethnic group discrimination.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations for Key Study Variables by Ethnicity

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PEGD | — | .06* | −.04 | −.07* | .14** | .13** |

| 2. Exploration | .13** | — | .64** | .20** | −.12** | −.08* |

| 3. Resolution | .10** | .72** | — | .26** | −.22** | −.18** |

| 4. Affirmation | .10** | .22** | .24** | — | −.29** | −.30** |

| 5. Depressive symptoms | .04 | −.14** | −.23** | −.34** | — | .84** |

Note. Correlations for Latino individuals are presented in upper diagonal of the table. Correlations for Black individuals are presented in lower diagonal of the table. PEGD = perceived ethnic group discrimination.

p < .05.

p < .01.

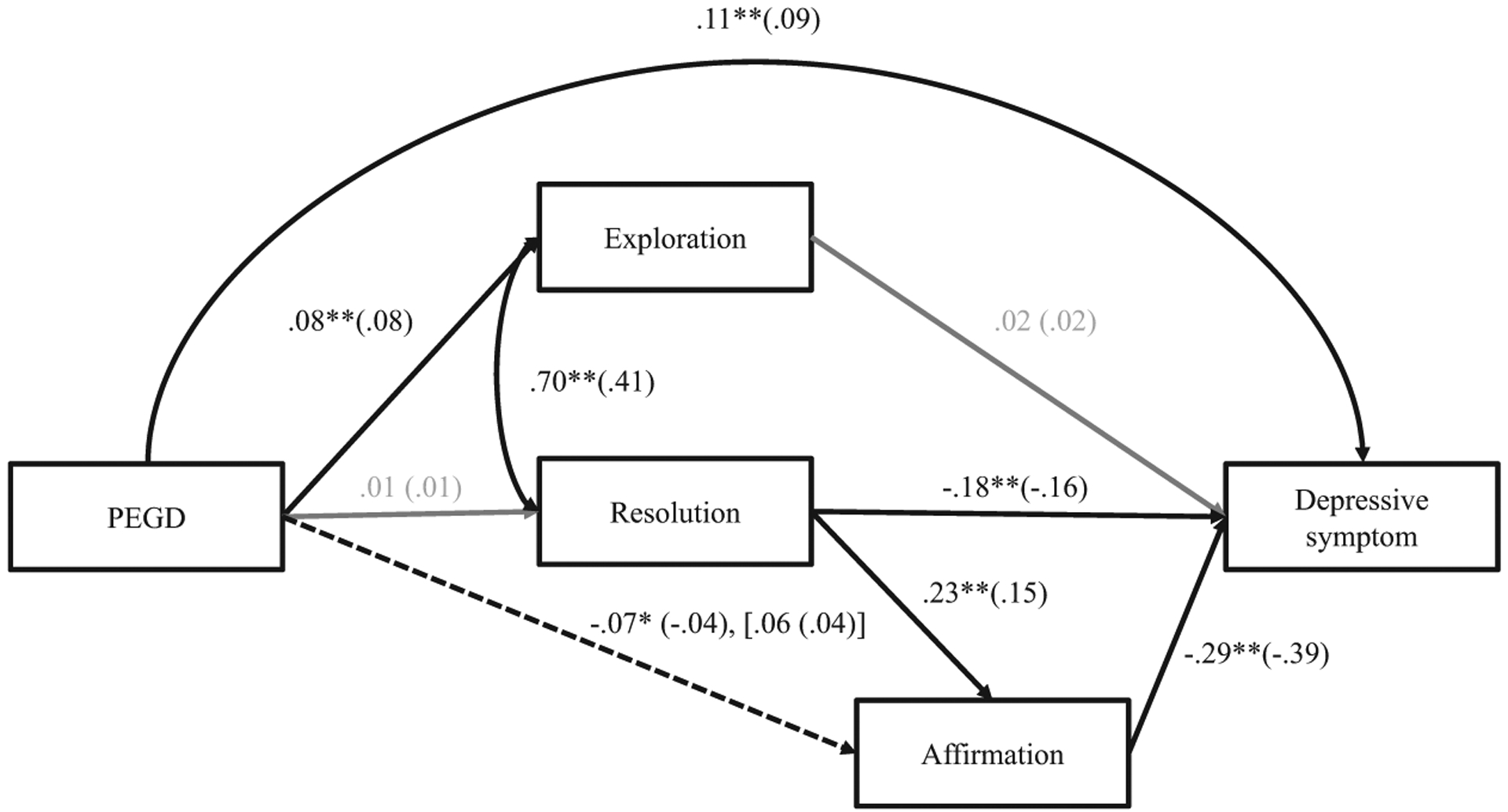

Tests of the hypothesized model indicated poor fit to the data, χ2(3) = 1208.79, p < .001; CFI = .15; RMSEA = .46; SRMR = .17. Modification indices suggested that a correlational path between ethnic identity resolution and ethnic identity affirmation would substantially improve the fit of the model. Therefore, we tested a revised model including this covariance. Tests of the revised model indicated improved fit over the hypothesized model, but still poor fit to the data, χ2(2) = 109.46, p < .001; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .17; SRMR = .05. Modification indices suggested that a direct path from ethnic identity resolution to ethnic identity affirmation would substantially improve the fit of the model. Therefore, we tested a second revised model adding this path. Results indicated that the revised model fit the data well, χ2(1) = 1.60, p = .21; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .02; SRMR <0.01. Results for the second revised model indicated that perceived ethnic group discrimination was positively related to exploration (β = .09, p < .001) and depressive symptoms (β = .10, p < .001), but was not significantly associated with resolution (β = .02, p = .52) or affirmation (β = −.02, p = .11). Ethnic identity exploration was correlated positively with ethnic identity resolution (β = .41, p < .001). However, the path from ethnic identity exploration to depressive symptoms was not significant (β = .02, p = .48). Ethnic identity resolution was positively associated with affirmation (β = .15, p < .001) and negatively related to depressive symptoms (β = −.16, p < .001). Affirmation was negatively related to depressive symptoms (β = −.39, p < .001).

Variability by Ethnic Group

The configural (unconstrained) model provided a good fit to the data, χ2(2) = 3.37, p = .19, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .01. The fit indices for the constrained model were χ2(11) = 21.46, p < .05, CFI = 0.99, RMSEA = .03, SRMR = .03. The chi-square difference test across ethnic groups was significant, Δχ2(9) = 18.09, p < .05, suggesting that some paths differed between Black and Latino students. The modification indices for the fully constrained model suggested that freeing the path from perceived ethnic group discrimination to affirmation would result in a substantial improvement in model fit. Therefore, a partially constrained model was tested that constrained all of the path coefficients across ethnic groups, except the path from perceived ethnic group discrimination to affirmation. The resulting model fit the data well, χ2(10) = 15.13, p = .13, CFI = 1.00, RMSEA = .02, SRMR = .03, and did not result in a significant drop in model fit relative to the fully unconstrained model (the better fitting model), Δχ2(8) = 11.76, p = .16. The partially constrained model (see Figure 1) indicated that only the path from perceived ethnic group discrimination to affirmation was significantly different between Black and Latino students; perceived ethnic group discrimination was negatively related to affirmation for Latino students (β = −.04, p < .05), but not related for Black students (β= .04, p = .14).

Figure 1.

The final model testing associations between perceived ethnic group discrimination, ethnic identity exploration, ethnic identity resolution, ethnic identity affirmation, and depressive symptoms; model controlled for gender and nativity. All path coefficients are standardized (unstandardized path coefficients are reported in parentheses). Significant paths are presented with a solid black line and the path that varies for Black and Latino students is presented with a dashed black line. The varying path estimates for Black students is presented in brackets. * p < .05. ** p < .01.

Tests for Mediation

Tests for mediation were conducted using bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals (CIs; MacKinnon et al., 2004). Specifically, a 95% CI was computed around the product of the two unstandardized path coefficients that comprised the mediating pathway. A confidence interval that does not include zero indicates significant mediation. Bootstrapping is used to provide internal replicability by randomly drawing 10,000 subsamples (with replacement) from the study sample and averaging the results across these subsamples.

Two of the indirect associations were statistically significant. First, perceived ethnic group discrimination was indirectly associated with depressive symptoms through ethnic identity affirmation among Latino students (unstandardized indirect path estimate = .02, 95% CI [.01, .03]). Second, resolution was indirectly associated with depressive symptoms through affirmation for both Black and Latino students (indirect path estimate = −.06, 95% CI [−.07, −.04]).

Discussion

Rates of depression among college-attending youth have doubled since the beginning of the 21st century (Kisch, Leino, & Silverman, 2005), and depression represents one of the more commonly reported mental health problems among college students (Eisenberg, Gollust, Golberstein, & Hefner, 2007; Hunt & Eisenberg, 2010). Given the paucity of studies examining associations between different types of perceived discrimination and mental health, and how different dimensions of ethnic identity relate to perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms, we advanced the literature by (a) examining the association between perceived ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms among Black and Latino college students, and (b) investigating whether multiple dimensions of ethnic identity (i.e., exploration, resolution, and affirmation) mediated this association. One prominent challenge in assessing perceptions of ethnic group discrimination is that it may be more difficult to detect than overt or interpersonal instances of discrimination (e.g., Spears Brown & Bigler, 2005). With regard to the current study, enhanced cognitive abilities (e.g., Steinberg, 2005) and advanced perspective-taking skills (Selman, 1976) among college-aged youth may make them more equipped, compared with children and adolescents, to identify forms of institutional discrimination related to ethnicity.

Perceived Ethnic Group Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms

In support of our study hypotheses, perceived ethnic group discrimination was positively related to depressive symptoms, providing evidence that perceptions of social attitudes and ethnic group barriers, and not just personal experiences with discrimination on the college campus, are notable risk factors for mental health problems among Black and Latino college students. Whereas the majority of prior literature examining the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health has focused primarily on the experiences of African Americans (see Williams et al., 2003, for a review), a growing body of literature indicates that perceived discrimination also represents a notable risk factor for Latinos’ mental health (e.g., Berkel et al., 2010; L. Torres & Ong, 2010; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007). Given that Latinos represent one of the fastest growing ethnic subgroups in the United States (Humes, Jones, & Ramirez, 2011) and in college enrollment rates (Aud, Fox, & Kewal-Ramani, 2010), it is important to understand how ethnic experiences, such as perceived ethnic group discrimination, can pose challenges to their mental health as well.

The Mediating Role of Dimensions of Ethnic Identity

Further contributing to extant literature on risk and resilience processes among ethnic minority young adults, tests of mediating relationships suggested ways that ethnic group discrimination might influence dimensions of ethnic identity directly, as well as how discrimination may indirectly impact depressive symptoms through these cultural factors. Thus, findings from the present study have the potential to inform intervention and prevention programs tailored toward ethnic minority groups on college campuses. A notable finding from the current study was that ethnic identity resolution was indirectly related to depressive symptoms through its direct relationship with ethnic identity affirmation among both ethnic groups. It is possible that resolution (and not exploration) was related to depressive symptoms in the current study because young adults are expected to exhibit psychosocial maturity, and to assume more adult roles and responsibilities, compared with adolescents who are expected to engage in more identity exploration (Côté, 2009; Erikson, 1968). Given this finding, counselors and other support providers should consider how to facilitate Black and Latino college students’ ethnic identity resolution. However, it should be noted that this study focused on a college sample, and that identity exploration may also be a normative and expected experience for college students (Arnett, 2000), who are likely able to further explore their ethnicity in a more (or less) diverse college environment or through university-based cultural organizations (e.g., Syed & Azmitia, 2009). Further research is needed to examine relationships among the different dimensions of ethnic identity to determine whether these processes replicate and whether they serve the same role for non-college-attending young adults (e.g., those who transition directly into work roles).

In addition, the present findings support prior research on ethnic identity formation (e.g., Phinney & Ong, 2007; Scottham, Cooke, Sellers, & Ford, 2010). Exploration and resolution have been described as processes through which individuals form an ethnic identity (Phinney & Ong, 2007). Affirmation has been described as one product (or dimension of content) of ethnic identity exploration (e.g., learning about one’s ethnic group) and resolution (e.g., establishing a sense of clarity about one’s ethnic group membership; Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, et al., 2014). Developmental theory indicates that engaging in ethnic identity exploration and resolving one’s ethnic identity can lead to ethnic identity achievement, and, in turn, positive feelings (affirmation) about one’s ethnic group are likely to follow (Phinney & Ong, 2007). Thus, among the ethnic minority college students in the current study, findings suggest that ethnic identity resolution is indirectly associated with depressive symptoms through its direct relationship with ethnic identity affirmation.

Findings also indicated that perceived ethnic group discrimination was positively associated with ethnic identity exploration, meaning that students who perceived that society held negative views about their ethnic group and thought that their ethnic group receives unfair treatment in society also reported engaging in higher levels of ethnic exploration. This finding is consistent with prior work suggesting that perceived discrimination might spark or initiate ethnic identity exploration (e.g., Branscombe et al., 1999; Phinney, 1992; Syed & Azmitia, 2008). Further, perceived ethnic group discrimination was not directly related to ethnic identity resolution or ethnic identity affirmation for either ethnic group, which was contrary to our hypotheses.1 However, ethnic identity exploration was highly correlated with ethnic identity resolution, which was predictive of ethnic identity affirmation. Therefore, it is possible that, as others (e.g., Brittian et al., 2013b; Phinney & Ong, 2007) have suggested, ethnic identity affirmation may be the most salient component of ethnic minority college students’ ethnic identity.

Variability Across Ethnic Groups

One notable ethnic group difference was observed. Specifically, perceived ethnic group discrimination was associated with lower ethnic identity affirmation for Latino young adults, but this direct association, although similar in magnitude, was positive and not significant for Black college students. This finding is consistent with prior work in which perceived discrimination was negatively related to ethnic identity affirmation among Mexican American adolescents (i.e., Romero & Roberts, 2003). Furthermore, the association between perceived ethnic group discrimination and mental health was mediated by ethnic identity affirmation among Latino young adults, but this association was not found among Black young adults. It is possible that Black college students in the current study may have attributed ethnic group discrimination to institutional or societal forces, whereas Latino college students may have attributed ethnic group discrimination to language and immigration and internalized these experiences. For example, Black students might have considered historical mistreatment (e.g., slavery, denial of voting rights, and “separate-but-equal” policies) when responding to questions about ethnic group discrimination, whereas Latino students may have contemplated current social barriers (e.g., laws around immigration and bilingual education). It is also possible that ethnic identity affirmation among Latino college students was more vulnerable to perceived ethnic group discrimination based on their expectations of equitable treatment. In comparison, Black students may have been prepared to encounter ethnic group discrimination due to parents’ socialization practices around preparation for bias (e.g., Harris-Britt et al., 2007; Hughes, 2003)—in contrast, preparation for bias is less prevalent among Latino families (Hughes et al., 2008). However, given that this is the first study of its kind to examine the associations between perceived ethnic group discrimination and dimensions of ethnic identity in two ethnic groups, further research is needed to determine the extent to which these differences are replicated in other samples. Furthermore, future research should explore how Black and Latino families prepare their youth for experiences with perceived ethnic discrimination, and how Black and Latino families foster various dimensions of youths’ ethnic identity.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Although our study advances the literature by investigating how dimensions of ethnic identity may relate to depressive symptoms, more research is still needed to provide a better understanding of how, and under what conditions, ethnic identity is associated with mental health. One limitation of the current study is the overrepresentation of women in the sample, which is not uncommon for a college population. Prior literature indicates that men and women differ in terms of experiences with perceived discrimination (Brodish et al., 2011; Hammond, 2012; Pérez, Fortuna, & Alegría, 2008) and ethnic identity formation (e.g., Umaña-Taylor et al., 2009). However, the small sample of men in the current study did not enable an examination of further moderation by gender in the patterns of associations found (e.g., tests of three-way interactions).

Second, the cross-sectional design limited our ability to draw directional inferences. For example, there is evidence to suggest that ethnic identification may increase perceptions of discrimination (e.g., Castillo et al., 2006; Major, Quinton, & Schmader, 2003; Sellers & Shelton, 2003). Although the direction of our hypothesized model (based on the rejection-identification model) was empirically supported, it was not possible to determine causality or directionality in the current study. In addition, the process of forming an ethnic identity may be cyclical, meaning that new experiences may prompt individuals to further explore their ethnicity and make new commitments to their ethnic group. In this case, prospective longitudinal research will be important for future studies.

An additional limitation to note is that the wording of the ethnic discrimination items specifically solicited perceptions of ethnic group discrimination (e.g., discrimination against my ethnic group in America is not a problem [reverse coded], opinions of people from my ethnic group are treated as less important than those of other ethnic groups), which may be less relevant for Black students. It is possible that the Black participants in the current study identified more strongly with being Black (a racial category) as opposed to African American (an ethnic category). Therefore, the measure may be more meaningful for this group if the term “race” was used instead of “ethnic” when attempting to capture perceived of overall group discrimination. However, given that this measure has been previously administered to Black populations, this limitation is speculative and future studies should further investigate this possibility. For example, as previously stated, the terms race and ethnicity may be indistinguishable for African Americans based on their history in the United States (e.g., Schwartz et al., 2014). Furthermore, future studies involving Black and Latino participants should consider that individuals from some ethnic/racial groups may consider themselves both Black and Latino, such as Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, and Cubans (Bailey, 2001; Hitlin, Brown, & Elder, 2007)—and, thus, such individuals might be studied as a separate group (e.g., Sanchez, 2013).

Whereas the current study focused on one form of perceived discrimination (i.e., perceived ethnic group discrimination), previous literature has identified several types of discriminatory experiences. For example, Smart Richman and Leary (2009) reviewed the literature on discrimination, perceived stigmatization, and ostracism, and identified potential mediators and moderators through which these different forms of rejection manifest in poor health outcomes. Thus, future studies should investigate how various forms of ethnic discrimination (e.g., interpersonal and institutional) impact mental health problems, and identify further factors (e.g., dimensions of ethnic identity) that promote mental health in light of these experiences.

Finally, we would be remiss not to acknowledge the literature on stereotype threat (internalizing negative stereotypes about one’s group that leads to poor performance; e.g., Steele & Aronson, 1995), although prior research on this specific social risk factor has focused primarily on performance outcomes, such as academic achievement (e.g., Schmader, Johns, & Forbes, 2008), and physical symptoms, such as elevated blood pressure (e.g., Osborne, 2007). Previous studies have not specifically investigated implications of stereotype threat for depressive symptoms; however, the literature does imply that long-term negative consequences of stereotype threat may include increased depressive symptoms. Emerging experimental research on stereotype threat indicates an additional avenue for future research. Sherman and colleagues (2013) observed that affirmation exercises (not specifically ethnic identity affirmation) mitigated the negative effect of overt or subtle racial and ethnic stereotypes and prejudices on Latino students’ academic performance (i.e., grades). Therefore, future research might examine whether ethnic identity affirmation represents a mitigating factor between social risk factors, such as stereotype threat, and mental health problems, such as depressive symptoms.

Conclusions

In sum, we attempted to elucidate the relationship between perceived ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms among college students from two ethnic groups (Black and Latino). By exploring dimensions of ethnic identity as mediators between perceived ethnic group discrimination and depressive symptoms, the present study highlighted one cultural factor (ethnic identity affirmation) that may serve as a risk reducing function for Latino young adults’ mental health in the context of ethnic group discrimination. Further, by examining different dimensions of ethnic identity, we have explicated how these dimensions may function together to reduce depressive symptoms. Perceived ethnic discrimination is a social stressor that ethnic minority individuals may encounter in many social contexts, including schools and in the workplace (e.g., Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006; Hughes & Dodge, 1997; Wong, Eccles, & Sameroff, 2003). Given that numerous studies have shown that perceived discrimination attributed to ethnic and racial group status impacts mental and physical health negatively (see, for example, Pascoe & Smart Richman, 2009; Williams et al., 2003), practitioners and university support services may want to consider how ethnic identity may function to reduce mental health problems among ethnic minority students.

Correction to Brittian et al. (2015).

In the article “Do Dimensions of Ethnic Identity Mediate the Association Between Perceived Ethnic Group Discrimination and Depressive Symptoms?” by Aerika S. Brittian, Su Yeong Kim, Brian E. Armenta, Richard M. Lee, Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Seth J. Schwartz, Ian K. Villalta, Byron L. Zamboanga, Robert S. Weisskirch, Linda P. Juang, Linda G. Castillo, and Monika L. Hudson (Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 2015, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 41–53. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0037531), the seventh column labeled “6” in Table 2 should have been omitted.

Acknowledgments

We thank our collaborators from the Multisite University Study of Identity and Culture (MUSIC) for their assistance in research design and data collection. We also thank the anonymous reviewers and the associate editor for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the quality of the article.

Footnotes

Given that ethnic identity exploration and resolution were correlated, we examined models that excluded either exploration or resolution, and tested the associations between perceived ethnic group discrimination and these variables independently. Consistent with the findings reported in the current study, perceived ethnic group discrimination was positively associated with exploration (when resolution was excluded) and was not significantly associated with resolution (when exploration was excluded).

THIS ARTICLE HAS BEEN CORRECTED. SEE LAST PAGE

Contributor Information

Aerika S. Brittian, University of Illinois at Chicago

Su Yeong Kim, The University of Texas at Austin.

Brian E. Armenta, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Richard M. Lee, University of Minnesota

Adriana J. Umaña-Taylor, Arizona State University

Seth J. Schwartz, University of Miami

Ian K. Villalta, Arizona State University

Byron L. Zamboanga, Smith College

Robert S. Weisskirch, California State University, Monterey Bay

Linda P. Juang, University of California, Santa Barbara

Linda G. Castillo, Texas A&M University

Monika L. Hudson, University of San Francisco

References

- Armenta BE, & Hunt JS (2009). Responding to societal devaluation: Effects of perceived personal and group discrimination on the ethnic group identification and personal self-esteem of Latino adolescents. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 12, 23–39. doi: 10.1177/1368430208098775 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ, & Tanner JL (Eds.) (2006). Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Ashmore RD, Deaux K, & McLaughlin-Volpe T (2004). An organizing framework for collective identity: Articulation and significance of multidimensionality. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 80–114. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aud S, Fox M, & Kewal-Ramani A (2010). Status and trends in the education of racial and ethnic groups (NCES 2010–015) U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey B (2001). Dominican-American racial/ethnic identities and the United States social categories. International Migration Review, 35, 677–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-7379.2001.tb00036.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berkel C, Knight GP, Zeiders KH, Tein J, Roosa MW, Gonzales NA, & Saenz D (2010). Discrimination and adjustment for Mexican American adolescents: A prospective examination of the benefits of culturally-related values. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 893–915. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00668.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Bourguignon D, Seron E, Yzerbyt V, & Herman G (2006). Perceived group and personal discrimination: Differential effects on personal self-esteem. European Journal of Social Psychology, 36, 773–789. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.326 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, & Harvey RD (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African-Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brittian AS, Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Derlan CL (2013a). An examination of biracial college youths’ family ethnic socialization, ethnic identity, and adjustment: Do self-identification labels and university context matter? Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19, 177–189. doi: 10.1037/a0029438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brittian AS, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Lee RM, Zamboanga BL, Kim SY, Weisskirch RS, … Caraway J (2013b). The moderating role of centrality on associations between ethnic identity affirmation and ethnic minority college students’ mental health. Journal of American College Health, 61, 133–140. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2013.773904 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodish AB, Cogburn CD, Fuller-Rowell TE, Peck S, Malanchuk O, & Eccles JS (2011). Perceived racial discrimination as a predictor of health behaviors: The moderating role of gender. Race and Social Problems, 3, 160–169. doi: 10.1007/s12552-011-9050-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Conoley CW, Choi-Person C, Archuleta DJ, Phoummarath MJ, & Van Landingham A (2006). University environment as a mediator of Latino ethnic identity and persistence attitudes. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 267–271. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.2.267 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, & Schwartz SJ (2013). Introduction to the special issue on college student mental health. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 291–297. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, & Rensvold RB (2002). Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling, 9, 233–255. doi: 10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cokley K (2007). Critical issues in the measurement of ethnic and racial identity: A referendum on the state of the field. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 224–234. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.224 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper DC, Mills PJ, Bardwell WA, Ziegler MG, & Dimsdale JE (2009). The effects of ethnic discrimination and socioeconomic status on Endothelin-1 among Black and Whites. American Journal of Hypertension, 22, 698–704. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté JE (2009). Identity formation and self-development in adolescence In Lerner RM & Steinberg L (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology: Vol. 1: Individual bases of adolescent development (3rd ed., pp. 266–304). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw K, Gotanda N, Peller G, & Thomas K (Eds.). (1995). Critical race theory. New York, NY: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cross WE Jr. (1995). The psychology of Nigrescence: Revising the Cross model In Ponterotto JG, Casas JM, Suzuki LA, & Alexander CM (Eds.), Handbook of multicultural counseling (pp. 93–122). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Donovan RA, Huynh QL, Park IJ, Kim SY, Lee RM, & Robertson E (2013). Relationships among identity, perceived discrimination, and depressive symptoms in eight ethnic-generational groups. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 397–414. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LM, & Romero AJ (2008). Coping with discrimination among Mexican descent adolescents. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 30, 24–39. doi: 10.1177/0739986307311431 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg D, Gollust S, Golberstein E, & Hefner J (2007). Prevalence and correlates of depression, anxiety, and suicidality among university students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 77, 534–542. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.77.4.534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK (2010). Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. New York, NY: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- French SE, Seidman E, Allen L, & Aber LJ (2006). The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 42, 1–10. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaylord-Harden NK, Ragsdale BL, Mandara J, Richards M, & Petersen AC (2007). Perceived support and internalizing symptoms in Black adolescents: Self-esteem and ethnic identity as mediators. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 77–88. doi: 10.1007/s10964-006-9115-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, & Pahl K (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and correlates. Developmental Psychology, 42, 218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DM, Cassidy EF, & Stevenson HC (2008). Acting “tough” in a “tough” world: An examination of fear among urban Black adolescents. Journal of Black Psychology, 34, 381–398. doi: 10.1177/0095798408314140 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond WP (2012).“Taking it like a man!” Masculine role norms as moderators of the racial discrimination-depressive symptoms association among African American men. American Journal of Public Health, 102(Suppl. 2), S232–S241. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Britt A, Valrie CR, Kurtz-Costes B, & Rowley SJ (2007). Perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem in Black youth: Racial socialization as a protective factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 17, 669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin S, Brown JS, & Elder GH Jr. (2007). Measuring Latinos: Racial classification and self-understandings. Social Forces, 86, 587–611. doi: 10.1093/sf/86.2.587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle R. (Ed.) (1995). Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria in fix indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D (2003). Correlations of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 15–33. doi: 10.1023/A:1023066418688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, & Dodge MA (1997). African American women in the workplace: Relationships between job conditions, racial bias at work, and perceived job quality. American Journal of Community Psychology, 25, 581–599. doi: 10.1023/A:1024630816168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes DL, Rivas D, Foust M, Hagelskamp CI, Gersick S, & Way N (2008). How to catch a moonbeam: A mixed-methods approach to understanding ethnic socialization processes in ethnically diverse families In Quintana S& McKown C(Eds.), Handbook of race, racism, and the developing child (pp. 226–277). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Humes KR, Jones NA, & Ramirez RR (2011). Overview of race and Hispanic origin 2010. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J, & Eisenberg D (2010). Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. Journal of Adolescent Health, 46, 3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsen S, & Nazroo JY (2002). Agency and structure: The impact of ethnic identity and racism on the health of ethnic minority people. Sociology of Health & Illness, 24, 1–20. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.00001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kisch J, Leino EV, & Silverman MM (2005). Aspects of suicidal behavior, depression, and treatment in college students: Results from the spring 2000 National College Health Assessment Survey. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 35, 3–13. doi: 10.1521/suli.35.1.3.59263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Cota MK, & Bernal ME (1993). The socialization of cooperative, competitive, and individualistic preferences among Mexican American children: The mediating role of ethnic identity. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 15, 291–309. [Google Scholar]

- Little TD, Card NA, Slegers D, & Ledford E (2007). Representing contextual factors in multiple-group MACS models In Little TD, Bovaird JA, & Card NA (Eds.), Modeling contextual effects in longitudinal studies (pp. 121–147). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Locks AM, Hurtado S, Bowman NA, & Oseguera L (2008). Extending notions of campus climate and diversity to students’ transition to college. The Review of Higher Education: Journal of the Association for the Study of Higher Education, 31, 257–285. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2008.0011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, & Williams J (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39, 99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, & O’Brien LT (2005). The social psychology of stigma. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 393–421. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Quinton WJ, & Schmader T (2003). Attributions to discrimination and self-esteem: Impact of group identification and situational ambiguity. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 39, 220–231. doi: 10.1016/S0022-1031(02)00547-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malcarne VL, Chavira DA, Fernandez S, & Liu PJ (2006). The scale of ethnic experience: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86, 150–161. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8602_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malcarne VL, Fernandez S, & Flores L (2005). Factorial validity of the Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scales for three American ethnic groups. Journal of Health Psychology, 10, 657–667. doi: 10.1177/1359105305055311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza-Denton R, Purdie V, Downey G, & Davis A (2002). Sensitivity to status-based rejection: Implications for African-American students’ transition to college. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83, 896–918. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.83.4.896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moradi B, & Risco C (2006). Perceived discrimination experiences and mental health of Latina/o American persons. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 411–421. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.53.4.411 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, & Muthén BO (1998–2010). Mplus user’s guide (6th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Noh S, & Kaspar V (2003). Perceived discrimination and depression: Moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. American Journal of Public Health, 93, 232–238. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.2.232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborne JW (2007). Linking stereotype threat and anxiety. Educational Psychology, 27, 135–154. doi: 10.1080/01443410601069929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pahl K, & Way N (2006). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity among urban Black and Latino adolescents. Child Development, 77, 1403–1415. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00943.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pascoe EA, & Smart Richman LS (2009). Perceived discrimination and health: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 531–554. doi: 10.1037/a0016059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez DJ, Fortuna L, & Alegría M (2008). Prevalence and correlates of everyday discrimination among U.S. Latinos. Journal of Community Psychology, 36, 421–433. doi: 10.1002/jcop.20221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1992). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176. doi: 10.1177/074355489272003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1993). A three-stage model of ethnic identity development In Bernal M & Knight G (Eds.), Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities (pp. 61–79). Albany, NY: SUNY Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS (1996). When we talk about American ethnic groups, what do we mean? American Psychologist, 51, 918–927. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.51.9.918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Alipuria LL (1990). Ethnic identity in college student from four ethnic groups. Journal of Adolescence, 13, 171–183. doi: 10.1016/0140-1971(90)90006-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney J, & Kohatsu E (1997). Ethnic and racial identity development and mental health In Schulenberg J, Maggs J, & Hurrelman K (Eds.), Health risks and developmental transitions in adolescence (pp. 420–443). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271–281. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse AL, Todd NR, Neville HA, & Carter RT (2012). Perceived racism and mental health among Black American adults: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59, 1–9. doi: 10.1037/a0026208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pincus F (2000). Discrimination comes in many forms: Individual, institutional and structural In Adams M(Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp. 31–34). New York, NY: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Quintana SM (2007). Racial and ethnic identity: Developmental perspectives and research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 259–270. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff L (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. doi: 10.1177/014662167700100306 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Hughes D, & Way N (2009). A preliminary analysis of associations among ethnic-racial socialization, ethnic discrimination, and ethnic identity among urban sixth graders. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19, 558–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00607.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Seaton EK, Markstrom C, Quintana S, Syed M, Lee RM, … Yip T. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in childhood and adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85, 40–57. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Syed M, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Markstrom C, French S, & Schwartz SJ, (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in the 21st century study group. Feeling good, happy, and proud: A meta-analysis of positive ethnic-racial affect and adjustment among diverse children and adolescents. Child Development, 85, 77–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, & Roberts RE (1998). Perception of discrimination and ethnocultural variables in a diverse group of adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 21, 641–656. doi: 10.1006/jado.1998.0185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, & Roberts RE (2003). The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity on discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 33, 2288–2305. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2003.tb01885.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Wolchik SA, & Sandler IN (1997). Preventing the negative effects of common stressors: Current status and future directions In Wolchik SA & Sandler IN (Eds.), Handbook of children’s coping: Linking theory and intervention (pp. 515–533). New York, NY: Plenum Press. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-2677-0_18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowley SJ, Sellers RM, Chavous TM, & Smith M (1998). The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 715–724. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.74.3.715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D (2013). Racial identity attitudes and ego identity formation in Dominican and Puerto Rican College Students. Journal of College Student Development, 54, 497–510. doi: 10.1353/csd.2013.0077 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmader T, Johns M, & Forbes C (2008). An integrated process model of stereotype threat effects on performance. Psychological Review, 115, 336–356. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Syed M, Yip T, Knight GP, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Rivas-Drake D, … Ethnic and Racial Identity in the 21st Century Study Group. (2014). Methodological issues in ethnic and racial identity research with ethnic minority populations: Theoretical precision, measurement issues, and research designs. Child Development, 85, 58–76. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, Weisskirch RS, & Rodriguez L (2009). The relationships of personal and ethnic identity exploration to indices of adaptive and maladaptive psychosocial functioning. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33, 131–144. doi: 10.1177/0165025408098018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scottham K, Cooke D, Sellers R, & Ford K (2010). Integrating process with content in understanding African American racial identity development. Self and Identity, 9, 19–40. doi: 10.1080/15298860802505384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Caldwell C, Schmeelk-Cone KH, & Zimmerman M (2003). Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 44, 302–317. doi: 10.2307/1519781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Copeland-Linder N, Martin PP, & Lewis RL (2006). Racial identity matters: The relationship between racial discrimination and psychological functioning in Black adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 16, 187–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2006.00128.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, & Shelton J (2003). The role of racial identity in perceived racial discrimination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 1079–1092. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.5.1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Smith M, Shelton J, Rowley S, & Chavous T (1998). Multidimensional model of racial identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 18–39. doi: 10.1207/s15327957pspr0201_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selman RL (1976). Social-cognitive understanding: A guide to educational and clinical practice In Lickona T (Ed.), Moral development and behavior: Theory, research, and social issues (pp. 299–316). New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DK, Hartson KA, Binning KR, Purdie-Vaughns V, Garcia J, Taborsky-Barba S, … Cohen GL (2013). Deflecting the trajectory and changing the narrative: How self-affirmation affects academic performance and motivation under identity threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104, 591–618. doi: 10.1037/a0031495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart Richman L, & Leary MR (2009). Reactions to discrimination, stigmatization, ostracism, and other forms of interpersonal rejection: A multimotive model. Psychological Review, 116, 365–383. doi: 10.1037/a0015250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spears Brown C, & Bigler RS (2005). Children’s perceptions of discrimination: A developmental model. Child Development, 76, 533–553. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2005.00862.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steele CM, & Aronson J (1995). Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 797–811. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9, 69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt J, Plunkett S, & Sands T (2006). Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development, 77, 1427–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, & Azmitia M (2008). A narrative approach to ethnic identity in emerging adulthood: Bringing life to the identity status model. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1012–1027. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, & Azmitia M (2009). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity during the college years. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19, 601–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00609.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor D, Wright S, Moghaddam F, & Lalonde R (1990). The personal/group discrimination discrepancy: Perceiving my group, but not myself, to be a target for discrimination. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 16, 254–262. doi: 10.1177/0146167290162006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Hugo Lopez M, Hamar Martinez J, & Velasco G (2012). When labels don’t fit: Hispanics and their views on identity. Washington, DC: Pew Hispanic Center; Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2012/04/04/when-labels-dont-fit-hispanics-and-their-views-of-identity/ [Google Scholar]

- Toomey RB, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Updegraff KA, & Jahromi LB (2013). Ethnic identity development and ethnic discrimination: Examining longitudinal associations with adjustment for Mexican-origin adolescent mothers. Journal of Adolescence, 36, 825–833. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres L, & Ong A (2010). A daily diary investigation of Latino ethnic identity, discrimination, and depression. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 16, 561–568. doi: 10.1037/a0020652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]