Abstract

Background and Aims

Cunoniaceae are woody plants with a distribution that suggests a complex history of Gondwanan vicariance, long-distance dispersal, diversification and extinction. Only four out of ~27 genera in Cunoniaceae are native to South America today, but the discovery of extinct species from Argentine Patagonia is providing new information about the history of this family in South America.

Methods

We describe fossil flowers collected from early Danian (early Palaeocene, ~64 Mya) deposits of the Salamanca Formation. We compare them with similar flowers from extant and extinct species using published literature and herbarium specimens. We used simultaneous analysis of morphology and available chloroplast DNA sequences (trnL–F, rbcL, matK, trnH–psbA) to determine the probable relationship of these fossils to living Cunoniaceae and the co-occurring fossil species Lacinipetalum spectabilum.

Key Results

Cunoniantha bicarpellata gen. et sp. nov. is the second species of Cunoniaceae to be recognized among the flowers preserved in the Salamanca Formation. Cunoniantha flowers are pentamerous and complete, the anthers contain in situ pollen, and the gynoecium is bicarpellate and syncarpous with two free styles. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that Cunoniantha belongs to crown-group Cunoniaceae among the core Cunoniaceae clade, although it does not have obvious affinity with any tribe. Lacinipetalum spectabilum, also from the Salamanca Formation, belongs to the Cunoniaceae crown group as well, but close to tribe Schizomerieae.

Conclusions

Our findings highlight the importance of West Gondwana in the evolution of Cunoniaceae during the early Palaeogene. The co-occurrence of C. bicarpellata and L. spectabilum, belonging to different clades within Cunoniaceae, indicates that the diversification of crown-group Cunoniaceae was under way by 64 Mya.

Keywords: Gondwana, fossil flowers, Argentina, palaeobotany, Danian, parsimony

INTRODUCTION

The distribution of Cunoniaceae throughout tropical and southern temperate forests suggests a deep Gondwanan legacy (Raven and Axelrod, 1974; Carpenter and Buchanan, 1993; Bradford et al., 2004). The family includes 28 extant genera and six tribes, but six of the genera are not assigned to a tribe (Fig. 1). Several species groups have intercontinental distributions, such as Cunonia L., Eucryphia Cav., Geissoieae, Schizomerieae and Weinmannia L. (Bradford and Barnes, 2001; Sweeney et al., 2004; Hopkins et al., 2013), but disentangling the relative importance of vicariance, long-distance dispersal, extinction and diversification in explaining these disjunctions depends on direct evidence of ancient distributions from the fossil record (Pole, 1994, 2001; Barnes et al., 2001; Sanmartín and Ronquist, 2004; Wilf and Escapa, 2015).

Fig. 1.

Summary of phylogenetic relationships among Cunoniaceae based on previous work (Bradford and Barnes, 2001; Sweeney et al., 2004; Hopkins et al., 2013).

The rich fossil record of Cunoniaceae in Australia provides evidence of at least 11 genera during the Cenozoic, but limited Cretaceous outcrops obscure the earlier history of the family on the continent (Barnes et al., 2001). Elsewhere, fossil occurrences of the family are comparatively rare; therefore, new discoveries have the potential to provide valuable information about the evolution and biogeographic history of Cunoniaceae (e.g. Gandolfo and Hermsen, 2017). In South America and the Antarctic Peninsula (Fig. 2), fossil woods (Petriella, 1972; Archangelsky, 1973; Baldoni and Askin, 1993; Raigemborn et al., 2009) and pollen (Archangelsky, 1973; Romero and Archangelsky, 1986; Troncoso, 1991; Zamaloa, 2000) ascribed to Cunoniaceae have been known for decades, but their possible relationships to extant tribes have not been evaluated through phylogenetic analyses.

Fig. 2.

Map of southern South America and the Antarctic Peninsula showing the occurrences of macrofossils identified to Cunoniaceae. (1) Williams Point Beds (Upper Cretaceous), Williams Point, Antarctica (Poole et al., 2000). (2) Salamanca Formation (Palaeocene), Chubut Province, Argentina (Jud et al., 2018a; this study). (3) Peñas Coloradas Formation (Palaeocene), Chubut Province, Argentina (Raigemborn et al., 2009). (4) Cerro Bororó Formation (Palaeocene), Chubut Province, Argentina (Petriella, 1972). (5) Fossil Hill Formation (Eocene), King George (25 de Mayo) Island, Antarctica (Zhang and Wang, 1994). (6) Sobral Formation (Palaeocene), Seymour (Marambio) Island, Antarctica (Poole et al., 2003). (7) Lopez de Bertodano Formation (Palaeocene), Seymour Island, Antarctica (Poole et al., 2003). (8) La Meseta Formation (Eocene), Seymour Island, Antarctica (Poole et al., 2003). (9) Fildes Formation (Eocene) King George Island, Antarctica (Poole et al., 2001, Francis and Poole, 2002). (10) Huitrera Formation (Eocene), Chubut Province, Argentina (Hermsen et al., 2010; Gandolfo and Hermsen, 2017). (11) Ligorio Márquez Formation (Eocene), Chile (Terada et al., 2006). (12) Ligorio Márquez Formation (Eocene), Chile (Carpenter et al., 2018) (13) ‘Forest Bed’ (Miocene), West Point Island, Falkland (Malvinas) Islands (Poole and Cantrill, 2007). (14) Seymour Island (Cretaceous), Antarctica (Pujana et al., 2018).

Here, we build on an earlier study (Jud et al., 2018a) by describing a second extinct species of Cunoniaceae from fossil flowers collected from the Salamanca Formation (earliest Palaeocene, ~64 Mya) in Patagonia, Argentina. The fossils have a combination of character states that indicates a close relationship with the syncarpous members of Cunoniaceae. We use phylogenetic analyses to explore the relationships of this new species and of Lacinipetalum spectabilum (Jud et al., 2018a) to other living and extinct members of the family. Finally, we discuss the implications of the co-occurrence of these two species at an early Palaeocene site in Patagonia for understanding the diversification of Cunoniaceae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Geological setting

The Salamanca Formation crops out in the San Jorge Basin in Patagonia, Argentina. It consists primarily of estuarine and shallow marine deposits and yields abundant plant micro- and megafossils (Berry, 1937; Romero, 1968; Petriella, 1972; Iglesias et al., 2007; Brea et al., 2008; Zucol et al., 2008; Futey et al., 2012; Jud et al., 2017, 2018a, b; Ruiz et al., 2017; Andruchow-Colombo et al., 2019; Hermsen et al., 2019). The Salamanca Formation overlies the Cretaceous Chubut Group and underlies the Palaeocene–Eocene Río Chico Group (Clyde et al., 2014; Comer et al., 2015). The fossils described here were collected from the Palacio de los Loros-2 (PL-2) locality in the lower part of the formation in south-eastern Chubut Province (Iglesias et al., 2007). The age of the PL-2 locality is constrained to geomagnetic polarity chron C28n. Comer et al. (2015) dated this chron to 64.67–63.49 Ma (early Danian) on the 2012 Geomagnetic Polarity Timescale, but the age of the lower boundary was revised to 64.535 ± 0.040 Ma by Clyde et al. (2016). This site yields an allochthonous assemblage of leaves, fruits and flowers, but so far Cunoniaceae have not been identified among the dicot leaves (Iglesias et al., 2007). The fossils are preserved in a grey clay shale that is interpreted as a swale between point-bar ridges of a tidally influenced fluvial channel that meandered across the coastal flats (Comer et al., 2015).

All necessary permits were obtained for this study, which complied with all relevant regulations. Coordinates for the locality are on file at the Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio (MEF), Trelew, Chubut, Argentina.

Fossil preparation

The fossils were collected over the course of four field seasons (2005, 2009, 2011 and 2012) and are curated at the Palaeobotanical Collection of the Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio (MPEF-Pb), Trelew, Chubut, Argentina. We captured images of macroscopic features with a Canon EOS 7D DSLR camera and microscopic details were photographed with a Nikon DS Fi1 camera mounted on a Nikon SMZ1000 stereoscope at the MEF. We used epifluorescence microscopy to examine the anthers for preserved pollen grains. We captured images of fossil and modern pollen grains with a Jeol NeoScope JCM-5000 scanning electron microscope at the Paleontological Research Institute (PRI), Ithaca, NY, USA. We processed the images using whole-image manipulations only with Adobe Photoshop CC 2017 (San Jose, CA, USA).

Molecular data

We began by obtaining the trnL–F and rbcL sequence data used by Bradford and Barnes (2001) from GenBank. We modified the dataset to include additional trnL–F and rbcL sequence data from GenBank. We also modified the dataset to reflect changes to the taxonomy since the work of Bradford and Barnes (2001), including the synonymy of Acsmithia Hoogland with Spiraeanthemum A.Gray (Pillon et al., 2009), the segregation of Karrabina Rozefelds & H.C.Hopkins from Geissois Labill. (Hopkins et al., 2013) and the rediscovery of Hooglandia ignambiensis (McPherson and Lowry, 2004). We used one exemplar species for each section of Weinmannia (Bradford, 2002). Next, we searched for additional informative sequences available on GenBank using the BLAST search tool and obtained matK and the trnH–psbA intergenic spacer region sequences for nine and seven species, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

GenBank accession numbers for each sequence used in the phylogenetic analyses

| Term | tRNA-Leu (trnL) trnL c–d | trnL–F intergenic spacer trnL e–F | rbcL | matK | trnH–psbA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ackama rosifolia | AF299162 | AF299215 | KT626660 | NA | NA |

| Acrophyllum australe | AF299168 | AF299221 | AF291926 | NA | NA |

| Anodopetalum biglandulosum | AF299175 | AF299228 | AF291932 | NA | NA |

| Bauera rubioides | AF299183 | AF299236 | L11174.2 | NA | NA |

| Bauera sessiliflora | AF299184 | AF299237 | NA | NA | NA |

| Brunellia colombiana | AF299181 | AF299234 | AF291937 | NA | NA |

| Brunellia oliveri | AF299182 | AF299235 | AF291938 | NA | NA |

| Caldcluvia paniculata | AF299163 | AF299216 | AF291922 | NA | NA |

| Callicoma serratifolia | AF299170 | AF299223 | AF291928 | KM894952 | NA |

| Ceratopetalum apetalum | NA | NA | KM895900 | KM894747 | KM895248 |

| Ceratopetalum gummiferum | AF299176 | AF299229 | L01895 | NA | NA |

| Codia discolor | AF299171 | AF299224 | AF291929 | NA | NA |

| Cunonia atrorubens | AF299154 | AF299207 | AF291918 | NA | NA |

| Cunonia capensis | AF299156 | AF299209 | NA | JX517913 | NA |

| Davidsonia jerseyana | AF299185 | AF299238 | AF206759 | AY935930 | NA |

| Davidsonia johnsonii | AF299186 | AF299239 | KM895905 | NA | KM895252 |

| Eucryphia cordifolia | AF299173 | AF299226 | AF291931 | KF224980 | NA |

| Eucryphia moorei | AF299174 | AF299227 | NA | NA | NA |

| Geissois superba | AF299166 | AF299219 | NA | NA | NA |

| Gillbeea adenopetala | AF299169 | AF299222 | AF291927 | NA | NA |

| Hooglandia ignambiensis | AY549639 | AY549640 | AY549641 | NA | NA |

| Karrabina benthamiana | AF299165 | AF299218 | AF291924 | NA | KM895230 |

| Lamanonia ternata | JX236029 | JX236029 | JX236032 | MG833493 | KF421056 |

| Opocunonia nymanii | NA | NA | MH826693 | NA | MH826497 |

| Pancheria engleriana | AF299158 | AF299211 | AF291919 | NA | NA |

| Platylophus trifoliatus | AF299177 | AF299230 | AF291933 | JX517817 | NA |

| Pseudoweinmannia lachnocarpa | AF299167 | AF299220 | AF291925 | NA | NA |

| Pullea glabra | AF299172 | AF299225 | AF291930 | NA | NA |

| Schizomeria ovata | AF299178 | AF299231 | KM895629 | KM894933 | KM895087 |

| Schizomeria serrata | JX236028 | JX236028 | JX236031 | NA | NA |

| Spiraeanthemum samoense | AF299180 | AF299233 | AF291936 | NA | NA |

| Spiraeanthemum ellipticum | EU867222 | EU867222 | AF291935 | NA | NA |

| Spiraeopsis celebica | AF299164 | AF299217 | AF291923 | NA | NA |

| Vesselowskya rubifolia | AF299160 | AF299213 | AF291920 | NA | NA |

| Weinmannia bangii | AF299145 | AF299198 | AF291915 | NA | NA |

| Weinmannia fraxinea | AF299149 | AF299202 | NA | AM889750 | GQ248402 |

| Weinmannia madagascarensis | AF299152 | AF299205 | AF291916 | NA | NA |

| Weinmannia minutiflora | AF299150 | AF299203 | NA | NA | NA |

| Weinmannia raiateensis | AF291917 | NA | GQ248402 | ||

| Lacinipetalum spectabilum | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Cunoniantha bicarpellata | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

We used Brunelliaceae (represented by Brunellia colombiana Cuatrec. and B. oliveri Britton) as the outgroup. Cunoniaceae form a clade with Brunelliaceae, Cephalotaceae and Elaeocarpaceae (Moody and Hufford, 2000; Bradford and Barnes, 2001; Sun et al., 2016; Valencia et al., 2020), but the sister taxon of Cunoniaceae is unclear. We did not use Cephalotaceae because they are morphologically specialized herbaceous pitcher plants and we did not use Elaeocarpaceae because the alignment of the trnL–F sequences with Cunoniaceae was ambiguous.

We aligned each locus independently using MUSCLE v. 3.8.31 in Aliview v. 1.18 (Larsson, 2014). The final concatenated matrix of sequence data (Supplementary Data NEXUS file) consists of the trnL intron (36 species, positions 1–618), the trnL–F intergenic spacer (36 species, positions 619–1167), rbcL (31 species, positions 1168–2638), matK (9 species, positions 2639–4151) and trnH–psbA (7 species, positions 4152–4752).

Morphological data

We examined the matrix of morphological characters used by Bradford and Barnes (2001) and modified several characters. Leaf arrangement is treated as unordered to remove any assumption about how this character evolves. Marginal tooth vascularization was replaced with secondary vein framework following Ellis et al. (2009). The stipule characters are modified from present/absent and lateral/interpetiolar/axillary to a single character where the various stipule types are considered alternative states along with the absence of stipules (Rutishauser and Dickison, 1989; Dickison and Rutishauser, 1990). We replaced the character of petal morphology (entire/incised) with a more complex set of four states to reflect the diversity of venation, shape, and type of incision across the family: ovate to obovate and single veined/large multiveined–obovate/flabellate incised/retuse. We used these new character states because we doubt the homology between the pattern of petal incision in Schizomerieae (Barnes and Rozefelds, 2000; Rozefelds and Barnes, 2002; Hopkins, 2018) and the retuse glandular petals of Gillbeea F.Muell. (Endress and Matthews, 2006). We also added new characters. These include winged rachis (absent/present), diffuse axial parenchyma in the wood (absent/present), irregular discontinuous bands of axial parenchyma in the wood (absent/present), regular bands of axial parenchyma in the wood (absent/present), number of parts per perianth whorl, number of stamens, anther attachment, number of carpels, texture of the ovary, type of stigma and accrescent calyx. We circumscribed character states with the aims of limiting polymorphic terminals and identifying clear discontinuities in interspecific variation. We coded the character states using descriptions and illustrations available in the literature and with herbarium specimens at the L. H. Bailey Hortorium Herbarium (BH), Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA (Supplementary Data Table S1). Missing data associated with the fossil taxa are unknown because the flowers have not yet been matched to co-occurring fossilized leaves, wood or fruits. All characters are treated as unordered. The final dataset comprises 41 taxa and 58 morphological characters. The character descriptions and morphological matrix are available online at the Morphobank website (www.morphobank.com; project P2600, matrix 26123).

Search strategy: parsimony analysis

We concatenated the molecular and morphological matrices using the ‘new matrix merge’ function in Winclada v. 1.99 spawned through ASADO version 1.99 (Nixon, 2008). The resulting matrix includes 41 taxa and 4810 total characters. Of these, 340 characters are parsimony-informative. We omitted all non-informative characters to optimize calculation of branch support values. To minimize a priori assumptions about character evolution and character importance, all characters were equally weighted and unpolarized. We conducted a tree search using NONA version 2.0 (Goloboff, 1999) spawned through ASADO version 1.99 (Nixon, 2008) using the following parameters: ‘hold 1000; mult*100; hold/100’, using the unconstrained ‘mult*max*’ search strategy. Bootstrap support values and jackknife values for branches were estimated by employing 1000 replicates, ten search pseudoreplicates and ten starting trees per pseudoreplicate. We then mapped the support values onto those branches also present in the strict consensus of the the most parsimonious trees.

RESULTS

Systematics

Order

Oxalidales Heintze.

Family

Cunoniaceae R.Br.

Genus

Cunoniantha Jud & Gandolfo gen. nov.

Type species

Cunoniantha bicarpellata Jud & Gandolfo sp. nov. (Figs 3 and 4A, B).

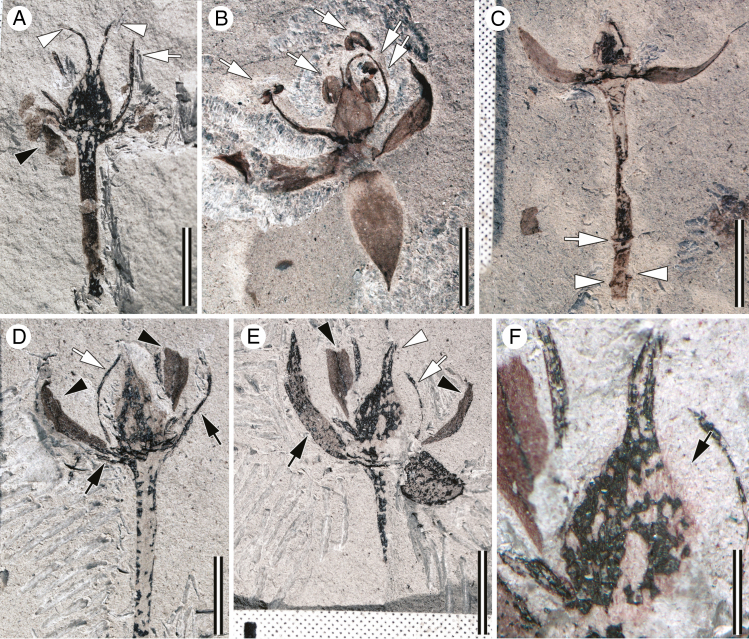

Fig. 3.

Longitudinal views of 35TCunoniantha bicarpellata Jud & Gandolfo gen. et sp. nov.35T specimens from PL-2 locality, Salamanca Formation. (A) Flower with pedicel, remains of petals (black arrowhead), filaments (white arrow), and a superior syncarpous ovary with two diverging styles (white arrowheads). MPEF-Pb 8523a. (B) Flower showing five anthers (arrows). MPEF-Pb 8545. (C) Flower attached to a partial possible thyrsoid/cymiform inflorescence. Note the abscission zone where the terminal flower is attached (at arrow) and the scars where other flowers or bracts were attached (at arrowheads). MPEF-Pb 8533. (D) Flower showing the pedicel, calyx (black arrows), petals (black arrowheads), filaments (white arrow) and a superior ovary. MPEF-Pb 8530b. (E) Counterpart of (D) showing pedicel, calyx (black arrow), petals (black arrowheads), filaments (white arrow) and a superior ovary with two parallel styles (white arrowhead). MPEF-Pb 8530a. (F) Close-up of (E) showing the pubescent ovary (black arrow). Scale bars: A–E = 3.0 mm; F = 1.0 mm.

Fig. 4.

Anther of 35TCunoniantha bicarpellata Jud & Gandolfo, gen et sp. nov. 35Tand scanning electron microscope micrographs of fossil and pollen of modern Cunoniaceae. (A) Close-up of an anther showing the longitudinal dehiscence slits and the absence of a connective extension. MPEF-Pb 8541a. (B) Two pollen grains 35Twith finely reticulate tectum35T (at arrows) preserved within the anthers of 35TCunoniantha bicarpellata. MPEF-Pb 35T97335T. (C) Prolate, tricolpate pollen grain Weinmannia glabra L.f. Note the perforate tectum. BH 000 054 033. (D) Prolate, tricolpate pollen grain Weinmannia glabra. Note the finely reticulate tectum. BH 000 054 033. (E) Oblate, tricolpate pollen grains of Opocunonia nymanii Schultr. See the finely reticulate tectum. BH 000 046 024. Scale bars: A = 0.5 mm, B = 10 µm, C35T–E = 5 µm.

Generic diagnosis

Flowers pedicellate, perfect, hypogynous, actinomorphic, with two perianth whorls of five organs; sepals ovate, inserted at the margin of the floral disc; petals obovate, entire, and equal to or greater than the length of the sepals; androecium of five stamens in one cycle, alternipetalous, anthers dorsifixed, without a connective extension, thecae with longitudinal dehiscence, pollen tricolpate, prolate and reticulate; gynoecium superior, bicarpellate, syncarpous with two free styles; stigmas non-capitate, ovary pubescent.

Specific diagnosis

As for the genus Cunoniantha.

Etymology

The name Cunoniantha refers to the morphology of the flowers typical of the syncarpous Cunoniaceae, and the epithet refers to the bicarpellate gynoecium.

Holotype

35MPEF-Pb 8523a, b.

Repository

Museo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio Paleobotany Collection (MPEF-Pb), Trelew, Chubut, Argentina.

Type locality

Palacio de Los Loros-2 (PL-2), Chubut, Argentina.

Stratigraphic position and age

Lower Salamanca Formation; Palaeocene, early Danian (Clyde et al., 2014; Comer et al., 2015).

Description

The flowers are perfect, actinomorphic, and borne on a pedicel ~5.8 mm long (5.0–7.9 mm) (Fig. 3). Most flowers were recovered isolated, but one is attached to an axis with sub-opposite lateral scars (Fig. 3C) indicating that the flowers were borne on an inflorescence. Inflorescence type is variable in Cunoniaceae, but this fragment is more consistent with a thyrsoid or cymiform inflorescence structure than a capitate, racemose or paniculiform structure. The perianth is composed of calyx and corolla, each with five parts and whorled phyllotaxis. The sepals are free and ovate, their bases are broadly attached at the rim of the floral cup and their apices are acute and straight. Sepals are 4.5 mm long by 2.0 mm wide (n = 9) (Fig. 3A). The petals are alternisepalous, narrow, 0.8–1.5 mm wide and 3.4–3.8 mm long, slightly obovate, and entire with a single midvein (Fig. 3D, E). Individual specimens have up to five stamens preserved (Fig. 3B); the stamen filaments taper from the base towards the anther and are 2.8–3.9 mm long (Fig. 3B); the anthers are dorsifixed, introrse, and versatile with longitudinal dehiscence along a ventral slit, ~1.1 mm long by 0.9 mm wide (n = 5) (Figs 3A and 4A). They contain prolate, tricolpate pollen grains (18 µm × 12 µm; n = 3) with a reticulate tectum (Fig. 4A, B). The gynoecium is superior, bicarpellate, and syncarpous with two free diverging styles (Fig. 3A, B). The ovary is pubescent (Fig. 3F), 2.4 mm long by 1.7 mm wide (n = 7). The styles are ~2.1 mm long (n = 5) and have indistinct stigmas (Fig. 3A, B, D). At the base of the gynoecium in many specimens there are abundant coalified remains, suggestive of an annular or segmented floral disc (Fig. 3A, B, D). Floral formula: *Ca5 Co5 A5G(2).

Material examined

MPEF-Pb 8522, 8523, 8527, 8529, 8530, 8533, 8534, 8536, 8540, 8541, 8542, 8545, 9731, 9732, 9733.

Phylogenetic analyses

Parsimony analysis yielded 92 equally short trees of 748 steps (Fig. 5). The consistency index is 0.56 and the retention index is 0.69. In all trees, Cunoniantha is nested in the ‘core Cunoniaceae’ clade of Bradford and Barnes (2001), but outside the tribes. Lacinipetalum is sister to extant members of Schizomerieae in all trees. Bootstrap support values are generally low around the position of the fossil species, but this is typical when including taxa with a high proportion of missing data (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Strict consensus of 92 most parsimonious trees based on simultaneous analysis of rbcL, trnL–F, matK and trnH–psbA sequence data and morphology. Note the positions of the fossil taxa within crown-group Cunoniaceae indicated by the daggers (†). Numbers above the branches are bootstrap support values followed by jackknife support values. Clades indicated by grey shading are tribes.

DISCUSSION

The position of Cunoniantha

Character states that support the placement of Cunoniantha within Cunoniaceae include a pentamerous, actinomorphic perianth with free sepals and petals, dorsifixed versatile anthers with longitudinal dehiscence, reticulate tricolpate pollen <20 μm long in maximum diameter (e.g. Fig. 4C–E), and a superior syncarpous bicarpellate gynoecium with two free styles and non-capitate stigmas (Bradford et al., 2004). Cunoniaceae are morphologically diverse; identification of morphological synapomorphies that apply to flowers across the entire family is challenging. Nonetheless, the combination of character states preserved in Cunoniantha falls within the range of variation for Cunoniaceae. Similar flowers occur in Saxifragaceae (Hideux and Ferguson, 1976; De Craene, 2010); however, Saxifragaceae are characterized by some combination of clawed petals, basifixed anthers and capitate stigmas (Soltis, 2007). These features are not present in Cunoniantha. Saxifragaceae are also less likely to be fossilized because they are herbaceous, and they are relatively recent arrivals to Patagonia (Deng et al., 2015). Matthews et al. (2001) found numerous similarities between Cunoniaceae and Anisophylleaceae, but flowers with bicarpellate gynoecia are exceptional in Anisophylleaceae, whereas this is the typical condition in most Cunoniaceae and in Cunoniantha.

The combination of undissected petals, only five stamens per flower, anthers without a thecal connective protuberance, and a thyrsoid/cymiform inflorescence structure observed in Cunoniantha does not match any extant genus. Nor does it match any of the previously described fossil genera that have been compared with Cunoniaceae (Matthews et al., 2001; Schönenberger et al., 2001; Poinar et al., 2008; Chambers et al., 2010; Poinar and Chambers, 2017, 2019; Jud et al., 2018a). Nonetheless, the results of our phylogenetic analysis indicate that Cunoniantha is nested within the syncarpous Cunoniaceae (Supplementary Data Fig. S1) and among the predominantly bicarpellate lineages (Supplementary Data Fig. S2). Bradford and Barnes (2001) recognized a ‘core Cunoniaceae’ clade that excludes Schizomerieae, Davidsonia and Bauera, but includes Eucryphia and is united by a shared deletion in the trnL–F spacer region (Fig. 1). More recent analyses also resolve this clade using maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference (Sweeney et al., 2004; Hopkins et al., 2013). Our analysis places Cunoniantha among this ‘core Cunoniaceae’ clade (Fig. 5).

The position of Lacinipetalum

Jud et al. (2018a) included the fossil Lacinipetalum spectabilum in a phylogenetic analysis of Schizomerieae with Davidsonia as the outgroup. In that analysis, Lacinipetalum was recovered as sister to Schizomerieae. We included Lacinipetalum in this broader analysis for three reasons. First, we updated some of the characters in this new analysis based on available data from the literature and a broader examination of morphological variation in the family (see Materials and methods section). Second, the absence of petals in Davidsonia means that it does not provide polarization for the characters related to the corolla that are preserved in the Lacinipetalum (Supplementary Data Fig. S3). Third, by using an ingroup consisting only of the fossil and extant Schizomerieae, Jud et al. (2018a) evaluated the most parsimonious position of Lacinipetalum within Schizomerieae, not the hypothesis that Lacinipetalum is more closely related to Schizomerieae than to other tribes. Indeed, this new analysis confirms a close relationship between Lacinipetalum and Schizomerieae (Fig. 5).

Biogeography and diversification of Cunoniaceae

Several extant genera in Cunoniaceae likely had broader distributions during the Palaeogene when the climate was warmer and wetter in Patagonia and when Australia was further south. These include Ceratopetalum Sm. (Holmes and Holmes, 1992; Barnes and Hill, 1999a; Gandolfo and Hermsen, 2017), Callicoma Andrews (Barnes and Hill, 1999b), Codia J.R.Forst & G.Forst (Barnes and Hill, 1999b), Eucryphia (Hill, 1991; Barnes and Jordan, 2000), Spiraeanthemum (Carpenter and Pole, 1995; Barnes et al., 2001) and Weinmannia (Carpenter and Buchanan, 1993; Barnes et al., 2001). The presence of Ceratopetalum, Eucryphia and Spiraeanthemum by the middle Eocene implies either a Cretaceous origin of crown-group Cunoniaceae or rapid diversification during the Palaeogene. Heibl and Renner (2012) presented the results of an analysis calibrated with early Eocene Eucryphia fossils (Barnes and Jordan, 2000) showing a late Eocene or younger divergence for most of the tribes in Cunoniaceae (except Spiraeanthemieae); however, given the Eocene–early Oligocene fossil occurrences discussed above, their ages are likely underestimates.

With the exception of the early Eocene Ceratopetalum (Gandolfo and Hermsen, 2017), most Upper Cretaceous and Palaeogene fossils from Patagonia and Antarctica assigned to Cunoniaceae are not included in any extant genus (Table 2). Nonetheless, fossil pollen from Upper Cretaceous and early Palaeogene sites across South America (Archangelsky, 1973; Romero and Archangelsky, 1986; Troncoso, 1991; Baldoni and Askin, 1993; Zamaloa, 2000; Barreda et al., 2020), Antarctica (Cranwell, 1959; Cantrill and Poole, 2012) and Australia (Kershaw and Sluiter, 1982; Hill and MacPhail, 1983; Christophel et al., 1987; Sluiter, 1991; Macphail, 1997; Alley, 1998; Barnes and Jordan, 2000) indicate that the family was widespread when floristic interchange was still possible without invoking trans-oceanic long distance dispersal. Similarly, fossil woods of Weinmannioxylon Petriella and Eucryphioxylon Poole Mennega & Cantrill are widespread in Upper Cretaceous and Palaeocene deposits in Patagonia (Petriella, 1972; Terada et al., 2006; Raigemborn et al., 2009) and Antarctica (Chapman and Smellie, 1992; Zhang and Wang, 1994; Poole et al., 2000, 2001, 2003; Cantrill and Poole, 2012; Pujana et al., 2018). However, these genera may or may not belong to the crown group. They have suites of plesiomorphic character states for the family including diffuse porosity, scalariform perforation plates, vessel-ray parenchyma pits that are scalariform to opposite, and diffuse axial parenchyma (Ingle and Dadswell, 1956; Dickison, 1980). Fossil leaves similar to Cunoniaceae have also been reported from the Eocene Ligorio Márquez Formation in South America, but these were not identified to genus (Carpenter et al., 2018).

Table 2.

Macrofossils attributed to Cunoniaceae from Antarctica, South America (Australian record summarized by Barnes et al., 2001)

| Taxon | Organs | Age | Locality | Continent | Reference | Latitude | Longitude |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eucryphiaceoxylon eucryphioides | Wood | Eocene | King George Island (8) | Antarctica | Poole et al., 2001 | −62.17 | −59.07 |

| Eucryphiaceoxylon eucryphioides | Wood | Cretaceous-Eocene? | Seymour Island (7) | Antarctica | Poole et al., 2003 | −64.2784 | −56.7324 |

| Eucryphiaceoxylon eucryphioides | Wood | Upper Cretaceous | James Ross Island (14) | Antarctica | Pujana et al., 2018 | −63.898 | −57.948 |

| Weinmannioxylon ackamoides | Wood | Palaeocene | King George Island (5) | Antarctica | Zhang and Wang, 1994 | −62.33 | −58.45 |

| Weinmannioxylon nordenskjoeldii | Wood | Upper Cretaceous | Williams Point (1) | Antarctica | Poole et al., 2000 | −62.475 | −60.137 |

| Weinmannioxylon trichospermoides | Wood | Upper Cretaceous | James Ross Island (14) | Antarctica | Pujana et al., 2018 | −63.876 | −57.906 |

| Weinmannioxylon sp. | Wood | Neogene | Falkland Island (13) | South America | Poole and Cantrill, 2007 | −51.35 | −60.66 |

| cf. Weinmannioxylon | Wood | Middle Eocene | Arroyo Cardenio River (11) | South America | Terada et al., 2006 | −46.763 | −71.775 |

| Weinmannioxylon multiperforatum | Wood | Palaeocene | Peñas Coloradas (3) | South America | Raigemborn et al., 2009 | −46.82 | −69 |

| Weinmannioxylon multiperforatum | Wood | Palaeogene | Chubut (4) | South America | Petriella, 1972 | −43.65 | −67.71 |

| Weinmannioxylon pluriradiatum | Wood | Palaeogene | Chubut (4) | South America | Petriella, 1972 | −43.65 | −67.71 |

| Ceratopetalum edgaroromeroi | Fruit | Eocene | Laguna del Hunco (10) | South America | Gandolfo and Hermsen, 2017 | −42.461 | −70.037 |

| undetermined Cunoniaceae | Leaf | Middle Eocene | Río Zeballos (12) | South America | Carpenter et al., 2018 | −46.834 | −71.856 |

| Cunoniantha bicarpellata | Flower | Palaeocene | PL-2, Chubut (2) | South America | This study | −45.912 | −69.214 |

| Lacinipetalum spectabilum | Flower | Palaeocene | LF, Chubut (2) | South America | Jud et al., 2018a | −45.69 | −68.611 |

| Lacinipetalum spectabilum | Flower | Palaeocene | PL-2, Chubut (2) | South America | Jud et al., 2018a | −45.912 | −69.214 |

| Lacinipetalum spectabilum | Flower | Palaeocene | PL-5, Chubut (2) | South America | Jud et al., 2018a | −45.909 | −69.226 |

Numbers following each locality correspond to points on the map in Fig. 2.

The discovery of Cunoniantha and Lacinipetalum from the early Palaeocene of Argentine Patagonia provides strong evidence that the diversification of crown-group Cunoniaceae was under way by 64 Mya. Although both genera are extinct, our phylogenetic analysis indicates that they belong to two different clades within the syncarpous Cunoniaceae. Together with other occurrences of fossil wood, pollen and Eucryphia leaves discussed above (Table 2), these fossils also indicate that the family was widespread across Gondwana by the Palaeocene, when warm climates permitted floristic exchange between South America and Australia via Antarctica (Hallam, 1995; Sanmartín and Ronquist, 2004; Cantrill and Poole, 2012; Wilf et al., 2013).

Evidence from fossil mammals suggests the land connection between South America and Antarctica was severed during the late Palaeocene or early Eocene (Reguero et al., 2014). Climate deterioration associated with global cooling and eventually deep-water currents through the Drake Passage (Lawver and Gahagan, 2003; Livermore et al., 2007; Eagles and Jokat, 2014) rendered the Antarctic peninsula inhospitable to Cunoniaceae by the mid-Eocene (Anderson et al., 2011). It appears that Cunoniaceae grew on the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands until at least the Miocene, but the age of these fossils is poorly constrained (Poole and Cantrill, 2007). During the late Palaeogene and Neogene, much of Patagonia also became increasingly moisture-limited (Palazzesi et al., 2014; Dunn et al., 2015). Suitable habitat for Cunoniaceae in South America retreated northward with the montane forests of the rising Andes. This dramatic reduction in available habitat area could explain the loss of some Cunoniaceae from South America, whereas Lamanonia, Weinmannia, Eucryphia and Caldcluvia survive.

Conclusions

Cunoniantha bicarpellata exhibits a mosaic of features consistent with Cunoniaceae. Phylogenetic analysis of morphological and molecular characters supports its position within crown-group Cunoniaceae among the syncarpous lineages. This is the second genus of Cunoniaceae from the Salamanca Formation described from fossilized flowers. Based on our phylogenetic analysis, Cunoniantha and Lacinipetalum together provide the oldest evidence of crown-group Cunoniaceae worldwide and show that the diversification was under way by 64 Mya.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at https://academic.oup.com/aob and consist of the following. Table S1: herbarium specimens at the L. H. Bailey Hortorium Herbarium, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA, examined for this study. NEXUS file: character matrix (trnL intron, trnL–F intergenic spacer, rbcL, matK, trnH–psbA). Figure S1: one of the most parsimonious trees showing the distribution of carpel number in Cunoniaceae. Figure S2: one of the most parsimonious trees showing the distribution of apocarpy and syncarpy in Cunoniaceae. Figure S3: one of the most parsimonious trees showing the distribution of petal type in Cunoniaceae.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank A. Iglesias, P. Wilf, P. Puerta, K. Johnson, M. Caffa, L. Canessa and many others for collecting the fossils. Thanks to the Secretaría de Cultura and Secretaría de Turismo y Areas Protegidas from Chubut Province, A. Balercia, Bochatey family, H. Visser and E. de Galáz for facilitating land access; and the Autoridad de Aplicación de la Ley de Patrimonio Paleontológico Argentino Ley 25,743 (Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales Bernardino Rivadavia, MACN) for permits in early stages of this work. The authors also thank E. Ruigomez and L. Reiner for assistance working with collections at 35TMuseo Paleontológico Egidio Feruglio (MEF) and fossil preparation. Thanks to the Paleontological Research Institute, Ithaca, NY, and B. Anderson for access to their scanning electron microscope, and personnel of the L. H. Bailey Hortorium Herbarium (BH), Cornell University. Thanks to K. C. Nixon (Cornell University) and to M. P. Simmons (Colorado State University) for constructive comments on an earlier version of the manuscript and to the reviewers and editor for suggestions that improved the manuscript. The authors declare no competing interests. Locality data and specimens are available in the Palaeobotanical Collection at the MEF, Trelew, Argentina. The matrix of morphological data is available on Morphobank (www.morphobank.org project P2600, matrix 24915).

FUNDING

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant numbers DEB-1556136, DEB-0918932, DEB-1556666, DEB-0919071, DEB-0345750, EAR-1925552, and EAR-1925755) and the Fulbright Foundation (M.A.G.).

LITERATURE CITED

- Alley NF 1998. Cainozoic stratigraphy, palaeoenvironments and geological evolution of the Lake Eyre Basin. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 144: 239–263. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JB, Warny S, Askin RA, et al. 2011. Progressive Cenozoic cooling and the demise of Antarctica’s last refugium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 108: 11356–11360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andruchow-Colombo A, Escapa, IH, Carpenter RJ, et al. 2019. Oldest record of the scale-leaved clade of Podocarpaceae, early Paleocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Alcheringa 43: 127–145. [Google Scholar]

- Archangelsky S 1973. Palinología del Paleoceno de Chubut. I. Descripciones sistemáticas. Ameghiniana 10: 339–399. [Google Scholar]

- Baldoni AM, Askin RA. 1993. Palynology of the lower Lefipán Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of Barranca de los Perros, Chubut province, Argentina. Part II. Angiosperm pollen and discussion. Palynology 17: 241–264. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RW, Hill RS. 1999a Ceratopetalum fruits from Australian Cainozoic sediments and their significance for petal evolution in the genus. Australian Systematic Botany 12: 635–645. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RW, Hill RS. 1999b Macrofossils of Callicoma and Codia (Cunoniaceae) from Australian Cainozoic sediments. Australian Systematic Botany 12: 647–670. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RW, Jordan GJ. 2000. Eucryphia (Cunoniaceae) reproductive and leaf macrofossils from Australian Cainozoic sediments. Australian Systematic Botany 13: 373–394. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RW, Rozefelds AC. 2000. Comparative morphology of Anodopetalum (Cunoniaceae). Australian Systematic Botany 13: 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes RW, Hill RS, Bradford JC. 2001. The history of Cunoniaceae in Australia from macrofossil evidence. Australian Journal of Botany 49: 301–320. [Google Scholar]

- Barreda VD, Zamaloa MC, Gandolfo MA, Jaramillo C, Wilf P. 2020. Early Eocene spore and pollen assemblages from the Laguna del Hunco fossil lake beds, Patagonia, Argentina. International Journal of Plant Sciences 181: 594–615. [Google Scholar]

- Berry EW 1937. A Paleocene flora from Patagonia. Johns Hopkins University Studies in Geology 12: 33–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford JC 2002. Molecular phylogenetics and morphological evolution in Cunonieae (Cunoniaceae). Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 89: 491–503. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford JC, Barnes RW. 2001. Phylogenetics and classification of Cunoniaceae (Oxalidales) using chloroplast DNA sequences and morphology. Systematic Botany 26: 354–385. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford JC, Hopkins HF, Barnes RW. 2004. Cunoniaceae . In: Kubitzki K, ed. The families and genera of vascular plants, Vol. VI. Dicotyledons. Berlin: Springer, 91–111. [Google Scholar]

- Brea M, Zamuner AB, Matheos SD, Iglesias A, Zucol AF. 2008. Fossil wood of the Mimosoideae from the early Paleocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Alcheringa 32: 427–441. [Google Scholar]

- Cantrill DJ, Poole I. 2012. The vegetation of Antarctica through geological time. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter RJ, Buchanan AM. 1993. Oligocene leaves, fruit and flowers of the Cunoniaceae from Cethana, Tasmania. Australian Systematic Botany 6: 91–109. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter RJ, Pole MS. 1995. Eocene plant fossils from the Lefroy and Cowan paleodrainages, Western Australia. Australian Systematic Botany 8: 1107–1154. [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter RJ, Iglesias A, Wilf P. 2018. Early Cenozoic vegetation in Patagonia: new insights from organically preserved plant fossils (Ligorio Márquez Formation, Argentina). International Journal of Plant Sciences 179: 115–135. [Google Scholar]

- Chambers KL, Poinar G Jr, Buckley R. 2010. Tropidogyne, a new genus of Early Cretaceous eudicots (Angiospermae) from Burmese amber. Novon 20: 23–29. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman JL, Smellie JL. 1992. Cretaceous fossil wood and palynomorphs from Williams Point, Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 74: 163–192. [Google Scholar]

- Christophel DC, Harris WK, Syber AK. 1987. The Eocene flora of the Anglesea locality, Victoria. Alcheringa 11: 303–323. [Google Scholar]

- Clyde WC, Wilf P, Iglesias A, et al. 2014. New age constraints for the Salamanca Formation and lower Río Chico Group in the western San Jorge Basin, Patagonia, Argentina: implications for Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction recovery and land mammal age correlations. Geological Society of America Bulletin 126: 289–306. [Google Scholar]

- Clyde WC, Ramezani J, Johnson KR, Bowring SA, Jones MM. 2016. Direct high-precision U–Pb geochronology of the end-Cretaceous extinction and calibration of Paleocene astronomical timescales. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 452: 272–280. [Google Scholar]

- Comer EE, Slingerland RL, Krause JM, et al. 2015. Sedimentary facies and depositional environments of diverse early Paleocene floras, north-central San Jorge Basin, Patagonia, Argentina. Palaios 30: 553–573. [Google Scholar]

- De Craene LPR 2010. Floral diagrams: an aid to understanding flower morphology and evolution. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cranwell LM 1959. Fossil pollen from Seymour Island, Antarctica. Nature 184: 1782–1785. [Google Scholar]

- Deng JB, Drew BT, Mavrodiev EV, Gitzendanner MA, Soltis PS, Soltis DE. 2015. Phylogeny, divergence times, and historical biogeography of the angiosperm family Saxifragaceae. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 83: 86–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickison WC 1980. Comparative wood anatomy and evolution of the Cunoniaceae. Allertonia 2: 281–321. [Google Scholar]

- Dickison WC, Rutishauser R. 1990. Developmental morphology of stipules and systematics of the Cunoniaceae and presumed allies. II. Taxa without interpetiolar stipules and conclusions. Botanica Helvetica 100: 75–95. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn RE, Strömberg CAE, Madden RH, Kohn MJ, Carlini AA. 2015. Linked canopy, climate, and faunal change in the Cenozoic of Patagonia. Science 347: 258–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eagles G, Jokat W. 2014. Tectonic reconstructions for paleobathymetry in Drake Passage. Tectonophysics 611: 28–50. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis B, Daly DC, Hickey LJ, et al. 2009. Manual of leaf architecture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Endress PK, Matthews ML. 2006. Elaborate petals and staminodes in eudicots: diversity, function, and evolution. Organisms Diversity & Evolution 6: 257–293. [Google Scholar]

- Francis JE, Poole I. 2002. Cretaceous and early Tertiary climates of Antarctica: evidence from fossil wood. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 182: 47–64. [Google Scholar]

- Futey MK, Gandolfo MA, Zamaloa MC, Cúneo NR, Cladera G. 2012. Arecaceae fossil fruits from the Paleocene of Patagonia, Argentina. Botanical Review 78: 205–234. [Google Scholar]

- Gandolfo MA, Hermsen EJ. 2017. Ceratopetalum (Cunoniaceae) fruits of Australasian affinity from the early Eocene Laguna del Hunco flora, Patagonia, Argentina. Annals of Botany 119: 507–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goloboff PA 1999. NONA version 2.0. Tucumán, Argentina: Published by the author. [Google Scholar]

- Hallam A. An outline of phanerozoic biogeography: Oxford: Oxford University Press, 256.; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Heibl C, Renner SS. 2012. Distribution models and a dated phylogeny for Chilean Oxalis species reveal occupation of new habitats by different lineages, not rapid adaptive radiation. Systematic Biology 61: 823–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermsen E, Jud NA, De Benedetti F, Gandolfo, MA. 2019. Azolla sporophytes and spores from the Late Cretaceous and Paleogene rocks of Patagonia, Argentina. International Journal of Plant Sciences 180: 737–754. [Google Scholar]

- Hermsen EJ, Gandolfo MA, Wilf P, Cuneo NRJohnsonKR. . 2010. Systematics of Eocene angiosperm reproductive structures from the Laguna del Hunco flora, NW Chubut province, Patagonia, Argentina. In: Geological Society of America Annual Meeting, Denver, Abstracts with Programs 4, 373. [Google Scholar]

- Hideux MJ, Ferguson IK. 1976. The stereostructure of the exine and its evolutionary significance in Saxifragaceae sensu lato . In: Ferguson IK, Muller J, eds. The evolutionary significance of the exine. London: Academic Press, 327–377. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RS 1991. Leaves of Eucryphia (Eucryphiaceae) from Tertiary sediments in south-eastern Australia. Australian Systematic Botany 4: 481–497. [Google Scholar]

- Hill RS, Macphail MK. 1983. Reconstruction of the Oligocene vegetation at Pioneer, northeast Tasmania. Alcheringa 7: 281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Holmes WBK, Holmes FM. 1992. Fossil flowers of Ceratopetalum Sm. (Cunoniaceae) from the Tertiary of East Australia. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales 113: 265–270. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins HCF 2018. The taxonomy and morphology of Schizomeria (Cunoniaceae) in New Guinea, the Moluccas and the Solomon Islands, with notes on seed dispersal and uses throughout the genus. Kew Bulletin 73: 11. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins HCF, Rozefelds AC, Pillon Y. 2013. Karrabina gen. nov. (Cunoniaceae), for the Australian species previously placed in Geissois, and a synopsis of genera in the tribe Geissoieae. Australian Systematic Botany 26: 167–185. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias A, Wilf P, Johnson KR, et al. 2007. A Paleocene lowland macroflora from Patagonia reveals significantly greater richness than North American analogs. Geology 35: 947–950. [Google Scholar]

- Ingle HD, Dadswell HE. 1956. The anatomy of the timbers of the south-west Pacific area IV. Cunoniaceae, Davidsoniaceae and Eucryphiaceae. Australian Journal of Botany 4: 125–152. [Google Scholar]

- Jud NA, Gandolfo MA, Iglesias A, Wilf P. 2017. Flowering after disaster: early Danian buckthorn (Rhamnaceae) flowers and leaves from Patagonia. PLoS ONE 12: e0176164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jud NA, Gandolfo MA, Iglesias A, Wilf P. 2018a Fossil flowers from the early Palaeocene of Patagonia, Argentina, with affinity to Schizomerieae (Cunoniaceae). Annals of Botany 121: 431–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jud NA, Iglesias A, Wilf P, Gandolfo MA. 2018b Fossil moonseeds from the Paleogene of West Gondwana (Patagonia, Argentina). American Journal of Botany 105: 927–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kershaw AP, Sluiter IR. 1982. Late Cenozoic pollen spectra from the Atherton Tableland, north-eastern Australia. Australian Journal of Botany 30: 279–295. [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A 2014. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics 30: 3276–3278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawver LA, Gahagan LM. 2003. Evolution of Cenozoic seaways in the circum-Antarctic region. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 198: 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Livermore R, Hillenbrand C-D, Meredith M, Eagles G. 2007. Drake Passage and Cenozoic climate: an open and shut case? Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 8: Q01005. [Google Scholar]

- Macphail MK 1997. Palynostratigraphy of the late cretaceous to tertiary basins in the Alice Springs District, Northern Territory. Canberra, Australia: Australian Geological Survey Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews ML, Endress PK, Schönenberger J, Friis EM. 2001. A comparison of floral structures of Anisophylleaceae and Cunoniaceae and the problem of their systematic position. Annals of Botany 88: 439–455. [Google Scholar]

- McPherson G, Lowry PP. 2004. Hooglandia, a newly discovered genus of Cunoniaceae from New Caledonia. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 91: 260–265. [Google Scholar]

- Moody M, Hufford L. 2000. Floral development and structure of Davidsonia (Cunoniaceae). Canadian Journal of Botany 78: 1034–1043. [Google Scholar]

- Nixon KC 2008. ASADO. Ithaca, NY: Published by the author. [Google Scholar]

- Palazzesi L, Barreda VD, Cuitiño JI, Guler MV, Tellería MC, Santos RV. 2014. Fossil pollen records indicate that Patagonian desertification was not solely a consequence of Andean uplift. Nature Communications 5: 3558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petriella BTP 1972. Estudio de maderas petrificadas del Terciario inferior del área central de Chubut (Cerro Bororó). Revista Museo de La Plata (NS), Paleontología 6: 159–254. [Google Scholar]

- Pillon Y, Hopkins HC, Munzinger J, Chase MW. 2009. A molecular and morphological survey of generic limits of Acsmithia and Spiraeanthemum (Cunoniaceae). Systematic Botany 34: 141–148. [Google Scholar]

- Poinar O Jr, Chambers KL. 2017. Tropidogyne pentaptera, sp. nov, a new mid-Cretaceous fossil angiosperm flower in Burmese amber. Palaeodiversity 10: 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Poinar O Jr, Chambers KL. 2019. Tropidogyne lobodisca sp. nov, a third species of the genus from mid-Cretaceous Myanmar amber. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas 13: 461–466. [Google Scholar]

- Poinar GO Jr, Chambers KL, Buckley R. 2008. An Early Cretaceous angiosperm fossil of possible significance in rosid floral diversification. Journal of the Botanical Research Institute of Texas 2: 1183–1192. [Google Scholar]

- Pole MS 1994. The New Zealand flora – entirely long-distance dispersal? Journal of Biogeography 21: 625–635. [Google Scholar]

- Pole MS 2001. Can long-distance dispersal be inferred from the New Zealand plant fossil record? Australian Journal of Botany 49: 357–366. [Google Scholar]

- Poole I, Cantrill D. 2007. The arboreal component of the Neogene Forest Bed, West Point Island, Falkland Islands. IAWA Journal 28: 423–444. [Google Scholar]

- Poole I, Cantrill DJ, Hayes P, Francis J. 2000. The fossil record of Cunoniaceae: new evidence from Late Cretaceous wood of Antarctica? Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 111: 127–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole I, Hunt RJ, Cantrill DJ. 2001. A fossil wood flora from King George Island: ecological implications for an Antarctic Eocene vegetation. Annals of Botany 88: 33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Poole I, Mennega AMW, Cantrill DJ. 2003. Valdivian ecosystems in the Late Cretaceous and Early Tertiary of Antarctica: further evidence from myrtaceous and eucryphiaceous fossil wood. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology 124: 9–27. [Google Scholar]

- Pujana RR, Iglesias A, Raffi ME, Olivero EB. 2018. Angiosperm fossil woods from the upper cretaceous of western Antarctica (Santa Marta Formation). Cretaceous Research 90: 349–362. [Google Scholar]

- Raigemborn MS, Brea M, Zucol AF, Matheos SD. 2009. Early Paleogene climate at mid latitude in South America: mineralogical and paleobotanical proxies from continental sequences in Golfo San Jorge basin (Patagonia, Argentina). Geologica Acta 7: 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Raven PH, Axelrod DI. 1974. Angiosperm biogeography and past continental movements. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 61: 539–673. [Google Scholar]

- Reguero MA, Gelfo JN, López GM, et al. 2014. Final Gondwana breakup: the Paleogene South American native ungulates and the demise of the South America–Antarctica land connection. Global and Planetary Change 123: 400–413. [Google Scholar]

- Romero EJ 1968. Palmoxylon patagonicum n. sp. del Terciario Inferior de la Provincia de Chubut, Argentina. Ameghiniana 5: 417–432. [Google Scholar]

- Romero EJ, Archangelsky S. 1986. Early Cretaceous angiosperm leaves from southern South America. Science 234: 1580–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozefelds AC, Barnes RW. 2002. The systematic and biogeographical relationships of Ceratopetalum (Cunoniaceae) in Australia and New Guinea. International Journal of Plant Sciences 163: 651–673. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz DP, Brea M, Raigemborn MS, Matheos SD. 2017. Conifer woods from the Salamanca Formation (early Paleocene), Central Patagonia, Argentina: paleoenvironmental implications. Journal of South American Earth Sciences 76: 427–445. [Google Scholar]

- Rutishauser R, Dickison WC. 1989. Developmental morphology of stipules and systematics of the Cunoniaceae and presumed allies. I. Taxa with interpetiolar stipules. Botanica Helvetica 99: 147–69. [Google Scholar]

- Sanmartín I, Ronquist F. 2004. Southern hemisphere biogeography inferred by event-based models: plant versus animal patterns. Systematic Biology 53: 216–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönenberger J, Friis EM, Matthews ML, Endress PK. 2001. Cunoniaceae in the Cretaceous of Europe: evidence from fossil flowers. Annals of Botany 88: 423–437. [Google Scholar]

- Sluiter IRK 1991. Early Tertiary vegetation and climates, Lake Eyre region, northeastern South Australia. In: Williams MAJ, de Deckker P, Kershaw AP, eds. The Cainozoic in Australia: a re-appraisal of the evidence. Special Publication 18. Sydney: Geological Society of Australia, 99–118. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE 2007. Saxifragaceae. In: Kubitzki K, ed. The families and genera of vascular plants. Flowering plants. Eudicots. Berlin: Springer, 418–435. [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Naeem R, Su J-X, et al. 2016. Phylogeny of Rosidae: a dense taxon sampling analysis. Journal of Systematics and Evolution 54: 363–391. [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney PW, Bradford JC, Lowry PP. 2004. Phylogenetic position of the New Caledonian endemic genus Hooglandia (Cunoniaceae) as determined by maximum parsimony analysis of chloroplast DNA. Annals of the Missouri Botanical Garden 91: 266–274. [Google Scholar]

- Terada K, Asakawa TO, Nishida H. 2006. Fossil woods from Arroyo Cardenio, Chile Chico Province, Aisen (XI) Region, Chile. In: Nishida H, ed. Post-Cretaceous floristic changes in Southern Patagonia, Chile. Tokyo: Chuo University, 57–65. [Google Scholar]

- Troncoso A 1991. Paleomegaflora de la Formación Navidad, Miembro Navidad (Mioceno), en el área de Matanzas, Chile central occidental. Boletín Museo Nacional de Historia Natural, Chile 42: 131–168. [Google Scholar]

- Valencia DJ, Murillo AJ, Parra OC, Neubig KM. 2020. Complete plastid genome sequences of two species of the Neotropical genus Brunellia (Brunelliaceae). PeerJ 8: e8392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilf P, Cúneo NR, Escapa IH, Pol D, Woodburne MO. 2013. Splendid and seldom isolated: the paleobiogeography of Patagonia. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 41: 561–603. [Google Scholar]

- Wilf P, Escapa IH. 2015. Green Web or megabiased clock? Plant fossils from Gondwanan Patagonia speak on evolutionary radiations. New Phytologist 207: 283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zamaloa MC 2000. Palinoflora y ambiente en el Terciario del nordeste de Tierra del Fuego, Argentina. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales nueva serie 2: 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S, Wang Q. 1994. Palaeocene petrified wood on the west side of Collins Glacier in the King George Island, Antarctica. Stratigraphy and palaeontology of Fildes Peninsula King George Island, Antarctica. State Antarctica Committee Monograph 3: 231–238. [Google Scholar]

- Zucol AF, Brea M, Matheos SD. 2008. Estudio preliminar de microrestos silíceos de la Formación Salamanca (Paleoceno inferior), Chubut, Argentina. In: Zucol AF, Osterrieth M, Brea M, eds. Fitolitos: estado actual de su conocimiento en América Del Sur. Mar Del Plata: Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata. EUDEM, 149–156. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.