Abstract

A growing body of evidence suggests that autophagy inhibition enhances the effectiveness of chemotherapy, especially in difficult-to-treat cancers. Existing autophagy inhibitors are primarily lysosomotropic agents. More specific autophagy inhibitors have not yet been developed. The microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B light chain 3B protein, LC3B, is an adapter protein that mediates key protein-protein interactions at several points in autophagy pathways. In this work, we use a known peptide ligand as a starting point to develop improved LC3B inhibitors. We obtained structure-activity relationships that quantify the binding contributions of peptide termini, individual charged residues, and hydrophobic interactions. Based on these data, we used artificial amino acids and diversity-oriented stapling to improve affinity and resistance to biological degradation while maintaining or improving LC3B affinity and selectivity. These peptides represent the highest-affinity LC3B-selective ligands reported to date, and they will be useful tools for further elucidation of LC3B’s role in autophagy and in cancer.

Introduction

Autophagy is a highly conserved eukaryotic pathway for recycling proteins, organelles, and other cellular components.[1–3] Dysregulated autophagy is associated with many diseases including lysosomal storage diseases, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancers.[1–6] Inhibiting autophagy has been suggested as a potential cancer therapy, though the relationship between autophagy and cancer is complex. Some evidence suggests autophagy is protective against tumorigenesis, so autophagy inhibition may not be useful for preventing or treating early-stage cancers.[7–9] However, advanced malignancies depend on autophagy as a quality control mechanism, much like they depend on the ubiquitin-proteasome system.[4,6] In fact, autophagy inhibition has been shown to be effective both in solid tumors and in hematological malignancies.[10–16] A number of clinical trials have demonstrated improved overall survival when combining autophagy inhibition with standard-of-care chemotherapy and radiation in aggressive cancers, including glioblastoma multiforme and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.[17–19] Currently, the only autophagy inhibitors used in clinical studies have been the FDA-approved antimalarials chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine. However, their mechanism of action is thought to target lysosomal function, which is a relatively nonselective route to autophagy inhibition.[4,20] Additional autophagy inhibitors frequently used in preclinical studies include the pan-PI3K inhibitor 3-methyladenine, as well as the V-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A1. However, these inhibitors also suffer from poor selectivity for autophagy, poor potency, or both.[21] This has prompted the development of more potent and selective inhibitors of autophagy.[22–36] Some of these efforts have focused on more potent chloroquine derivatives,[22–25] while others have targeted kinases specific to autophagy such as Ulk1 and Vps34 (a class III PI3K).[26–36] These selective autophagy inhibitors hold promise as anti-cancer therapeutics, as they have shown anti-proliferative activity when co-administered with standard chemotherapies, and also induction of anti-tumor immune response when co-administered with PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors.[26,30,36–45] These efforts support a continued need for selective autophagy inhibitors as potential anti-cancer agents.

As an alternative to kinase inhibition, one strategy for developing selective autophagy inhibitors is to antagonize key protein-protein interactions. The Atg8 protein family mediates critical protein-protein interactions at several points in autophagic pathways, and thus represents an ideal target for selective inhibition (Fig. 1a). In humans, Atg8 proteins are comprised of two protein subclasses, LC3 (LC3A, LC3B, and LC3C) and GABARAP (GABARAP, GABARAPL1, and GABARAPL2). In this work, we focus on LC3B since it is the most-studied human Atg8 protein, and one with clear connections to cancer. For instance, Mikhaylova and colleagues demonstrated in clear cell renal carcinoma that LC3B expression correlated with higher tumor grade, and LC3B was a direct target for miR-204, a microRNA frequently upregulated in VHL-mutated clear cell renal carcinomas.[46] At the same time, several studies have demonstrated that other Atg8 proteins like GABARAP can function as tumor suppressors.[47,48] Therefore, being able to inhibit LC3B selectively over GABARAP would allow a direct pharmacological method for investigating these proteins’ roles in autophagy and in cancer.

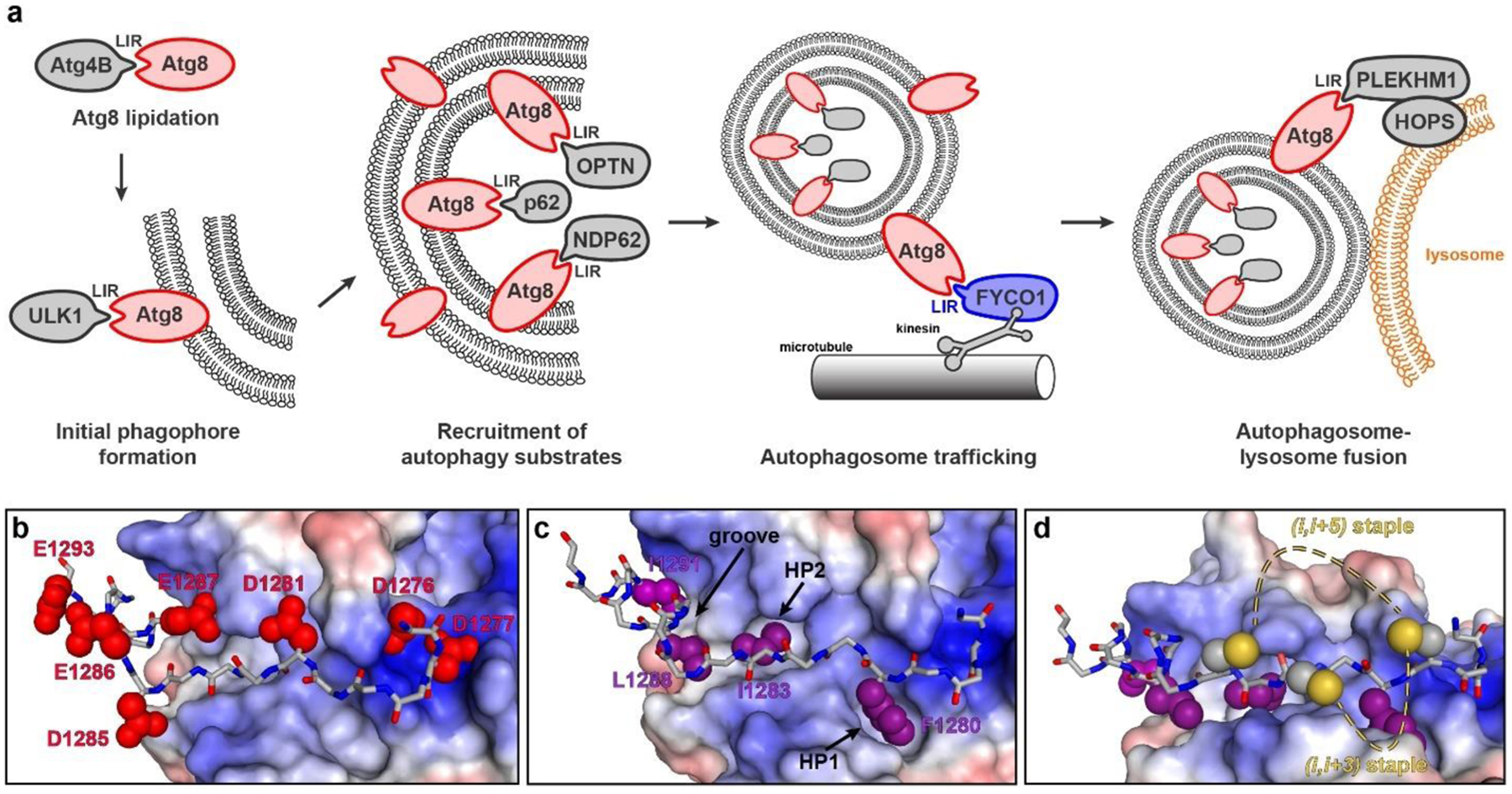

Figure 1.

Protein-protein interactions of Atg8 proteins involving the LC3-interacting region (LIR) motif. a) LIR-dependent protein-protein interactions are involved in several stages of autophagy, including phosphatidylethanolamine conjugation to Atg8 proteins[51], ULK1 initiation complex tethering and early phagophore formation[49,50], selective cargo recruitment including mitophagy adapters[54] and ubiquitinylated aggregate adapter p62[52], autophagosome transport[53], and autophagosome-lysosome fusion.[55,56] b-d) Crystal structure of a LIR motif-containing peptide from FYCO1 bound to LC3B (PDB: 5CX3).[59] These images highlight key positions investigated in this study, including hydrophobic pockets (b), charged residues (c), and positions in close proximity suitable for stapling (d).

LC3B directly interacts with numerous autophagy cargo receptors, initiation complexes, processing enzymes, adapters, and trafficking proteins. Its many binding partners all use a conserved “LC3-interacting region” (LIR) motif to bind LC3 (Fig. 1a).[49–56] We hypothesized that LIR motif peptides could be used as starting points to develop selective inhibitors of LC3B. Specifically, we started with a LIR motif peptide derived from the microtubule-associated vesicle transport protein FYCO1.[53,57] The LIR motif within FYCO1 is among the higher-affinity LIR motifs reported to date, and it is the most selective for LC3 proteins over GABARAPs. [49,57–59] Here we report detailed structure-activity relationships of the FYCO1 LIR motif with LC3B. We also applied artificial side chains to improve binding to key hydrophobic pockets. Finally, we designed stapled peptides which maintain selectivity for LC3B but improve affinity and biological stability. Notably, most peptide stapling strategies are limited to helical motifs. Because LIR motifs bind LC3B in an extended conformation, we applied an innovative diversity-oriented stapling strategy that does not assume any specific secondary structure.[60–68]

Results

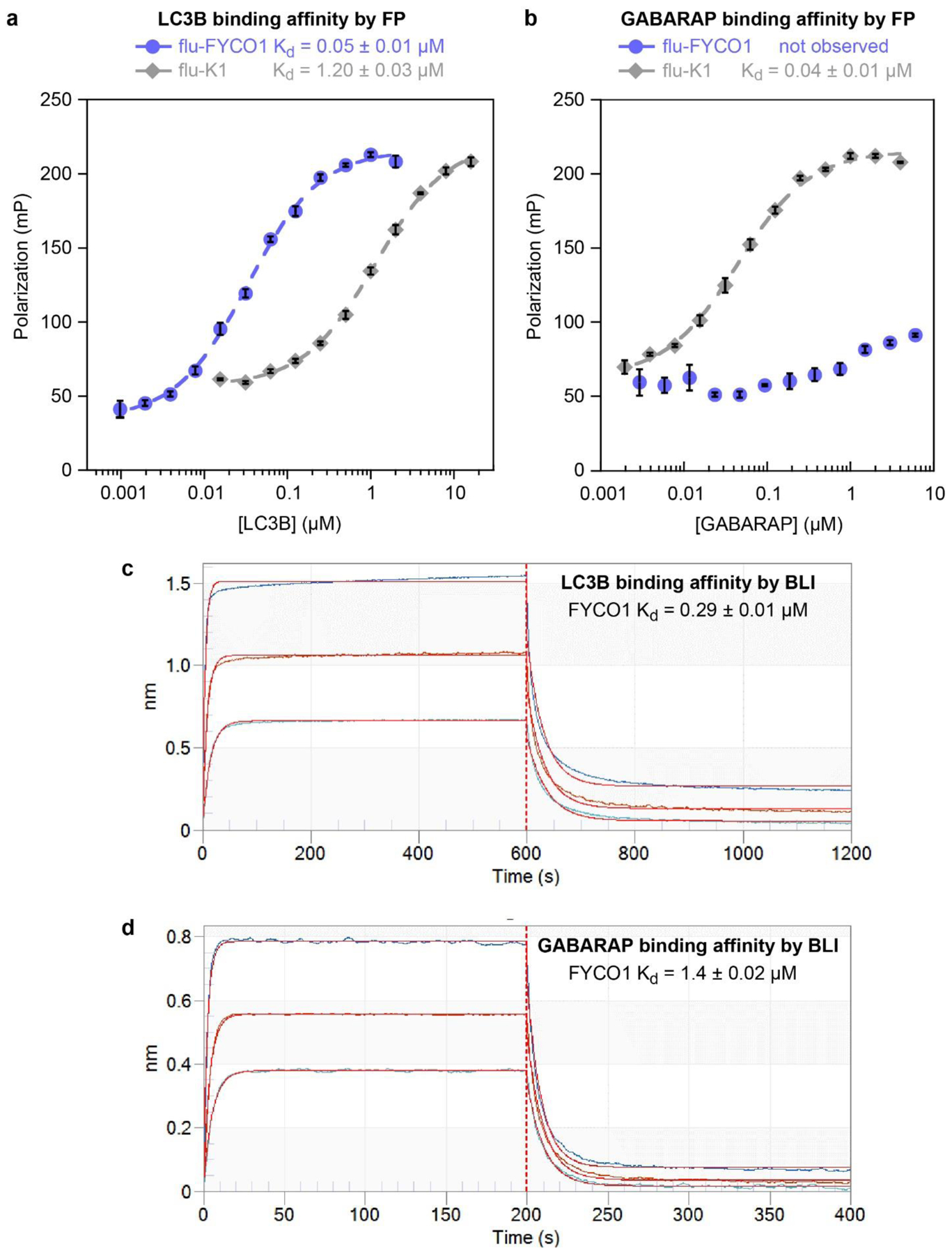

Many interactions between LC3B and various LIR motif-containing proteins have been validated, but only a handful of studies have quantitatively measured binding affinities of LIR peptides for LC3B.[49,57–59,69] To compare directly to prior work, we explored two different binding assays for measuring binding of synthetic peptides to recombinant LC3B and recombinant GABARAP. One assay used fluorescence polarization and the other used biolayer interferometry (BLI). As controls for these assays, we prepared analogs of two previously reported LIR peptides, FYCO1 (residues D1276 through E1293), which is selective for LC3B over GABARAP, and K1, which is selective for GABARAP over LC3B.[57,70] In fluorescence polarization assays, we measured a Kd value of 50 nM for fluorescein-labeled FYCO1 peptide (flu-FYCO1) binding to LC3B, and no appreciable binding of flu-FYCO1 to GABARAP at concentrations as high as 4 μM (Fig. 2a–b, Fig. S1,2). As a positive control for GABARAP binding, we prepared fluorescein-labeled K1 peptide (flu-K1) and measured Kd values of 40 nM for flu-K1 binding GABARAP, and 1.2 μM for flu-K1 binding to LC3B. (Fig. 2a–b, Fig. S1,2). These data are roughly consistent with prior work with the FYCO1 and K1 peptides.[57,59,70]

Figure 2.

Binding affinities of FYCO1 and K1 peptides with the human Atg8 proteins LC3B and GABARAP. a,b) Fluorescence polarization binding assays for fluorescein-labeled FYCO1 peptide (flu-FYCO1) with recombinant human GABARAP and LC3B proteins. Peptide K1, a previously described GABARAP-selective peptide, is used as a positive control. Curve fitting was performed using KaleidaGraph graphing software as described.[60] Average Kd values and standard error were calculated from the individual curve fits of three independent replicates, each with three technical replicates (individual replicates with raw polarization values shown in Fig. S1,2). c,d) Biolayer interferometry data (BLI) for biotinylated FYCO1 peptide (FYCO1) with recombinant human GABARAP and LC3B. BLI was performed with 0.5 μg/mL of biotinylated peptides loaded onto streptavidin-coated biosensors with serial dilutions of protein at 30 °C. Association and dissociation steps were measured for 200 seconds each. Curve fitting was performed using the Octet DataAnalysis software (FortéBio) and Kd values were calculated as described in Methods. Shown are primary data (dark blue, orange and light blue traces) and curve fits (red curves) for incubation with 1.5, 0.75, and 0.375 μM for LC3, and 4, 2, and 1 μM for GABARAP. Average Kd values and standard errors of the mean (Tables 1 and 2) were calculated from the individual curve fits of three independent replicates (Tables S2–7).

While these assays were comparable to prior fluorescence polarization assays performed with similar dye-labeled peptides, we sought a more efficient and convenient method for measuring the binding of LC3B and GABARAP with synthetic peptides. We found that biolayer interferometry (BLI) allowed for rapid, reproducible results for protein-peptide binding using biotinylated peptides immobilized on BLI biosensors. In BLI assays with biotinylated FYCO1 peptide (FYCO1), we measured Kd values of 290 nM for LC3B, and 1.4 μM for GABARAP (Fig. 2b). In BLI assays with biotinylated K1 peptide (K1), we measured Kd values of 19 μM for LC3B and 390 nM for GABARAP (Fig. S3). Overall, these data more closely match prior work with the FYCO1 and K1 peptides than the data from the fluorescence polarization assay. Thus, we proceeded to use BLI with biotinylated peptides to measure the LC3B and GABARAP binding affinities of FYCO1 peptides and their analogs.

The FYCO1 peptide consists of residues 1276 through 1293 of the human FYCO1 protein, with a C-terminal tryptophan included to allow more accurate spectrophotometric concentration determination; the core LIR motif within FYCO1 is residues F1280 through I1283.[57] First, we assessed the importance of residues outside the core LIR motif. Truncating the four N-terminal residues (peptide 1276–1279) completely abrogated binding, implying an important role for these residues (Table 1). By contrast, truncating the five C-terminal residues (peptide 1289–1293) led to a 10-fold loss in binding affinity (Kd of 3.1 μM compared to 0.29 μM for the full-length FYCO1 peptide). Truncating only two C-terminal residues (peptide 1292–1293) led to a 1.6-fold loss in binding affinity (Kd of 0.46 μM), implying an important role for residues 1289–1291. These results are consistent with the binding mode observed in the crystal structure of the FYCO1 peptide bound to LC3B, in which I1291 makes hydrophobic contacts in a shallow groove of LC3B, while Q1292 and E1293 face solvent (Fig. 1c).

Table 1.

Binding affinities for FYCO1-derived peptides with LC3B protein. BLI and curve fitting were performed as described in Figure 2 and in Methods. Average Kd values and standard errors of the mean (Tables 1 and 2) were calculated from the individual curve fits of three independent replicates (Tables S2–4). 2 denotes 2-naphthylalanine, 1 denotes 1-naphthylalanine, denotes 5,5-dimethylnorleucine, denotes tert-butylalanine, and r denotes D-arginine. All peptides have a C-terminal amide group and an N-terminal biotin separated from the peptide by two beta-alanine residues. ND denotes no binding affinity detected up to 20 μM LC3B protein.

| Name | Sequence | Kd (μM) | Std Err (μM) | Fold change from FYCO1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FYCO1 | DDAVFDIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.29 | 0.01 | 1.0 |

| Termini Truncations | ||||

| 1276–1279 | FDIITDEELCQIQEW | ND | ND | ND |

| 1289–1293 | DDAVFDIITDEELW | 3.1 | 0.6 | 11 |

| 1292–1293 | DDAVFDIITDEELCQIW | 0.46 | 0.03 | 1.6 |

| Gln/Asn Scan of Negative Residues | ||||

| D1276N | NDAVFDIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.35 | 0.02 | 1.2 |

| D1277N | DNAVFDIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.48 | 0.04 | 1.7 |

| D1281N | DDAVFNIITDEELCQIQEW | 1.1 | 0.2 | 3.8 |

| D1285N | DDAVFDIITNEELCQIQEW | 0.41 | 0.02 | 1.4 |

| E1286Q | DDAVFDIITDQELCQIQEW | 0.76 | 0.07 | 2.6 |

| E1287Q | DDAVFDIITDEQLCQIQEW | 2.7 | 0.4 | 9.3 |

| E1293Q | DDAVFDIITDEELCQIQQW | 0.30 | 0.005 | 1.0 |

| D1276N/D1277N | NNAVFDIITDEELCQIQEW | 1.2 | 0.03 | 4.1 |

| Hydrophobic Mutations | ||||

| F1280Nap2 | DDAV2DIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.48 |

| F1280Nap1 | DDAV1DIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.59 |

| I1283F | DDAVFDIFTDEELCQIQEW | 5.9 | 0.2 | 20 |

| I1283Nap2 | DDAVFDI2TDEELCQIQEW | 2.6 | 0.1 | 9.0 |

| L1288NL5 | DDAVFDIITDEECQIQEW | 0.58 | 0.04 | 2.0 |

| L1288tbA | DDAVFDIITDEECQIQEW | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.86 |

| I1291tbA | DDAVFDIITDEELCQQEW | 0.44 | 0.03 | 1.5 |

| I1291F | DDAVFDIITDEELCQFQEW | 0.73 | 0.03 | 2.5 |

| Introduction of Positive Charge | ||||

| A1278r | DDrVFDIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.90 | 0.06 | 3.1 |

| R-FYCO1 | RDDAVFDIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.20 | 0.01 | 0.69 |

| RR-FYCO1 | RRDDAVFDIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.33 | 0.01 | 1.1 |

| Optimized Combination | ||||

| Comb1 | RDDAV2DIITDEEαCQIQEW | 0.12 | 0.004 | 0.41 |

In general, LIR motifs that bind LC3B often have multiple negatively charged residues within and surrounding the core LIR motif.[71] It is unclear from the literature whether these negative charges contribute substantially to the binding affinity. Thus, we next measured the individual contributions of each of the seven negatively charged residues in the FYCO1 peptide (Fig. 1b). We prepared a panel of analogs that represented individual substitutions of asparagine in place of aspartate, or glutamine in place of glutamate (Table 1). While we found that an N-terminal truncation completely abrogated binding (peptide 1276–1279), peptides D1276N and D1277N each had well under 2-fold reduced affinity, with Kd values of 0.35 and 0.48 μM, respectively (Table 1). Following up on these results, we prepared and tested a double mutant, D1276N/D1277N. D1276N/D1277N had a Kd of 1.2 μM, which is poorer than a simple combination of the effects of the individual substitutions. These data suggest that hydrogen bonding or other non-electrostatic interactions at the N-terminus contribute to LC3B binding, and also that the charged N-terminus contributes to the binding interaction in a cooperative manner.

Most of the other negatively charged residues appear to contribute very little to the binding affinity of the FYCO1 peptide, including D1276, D1277, D1285, and E1293 (Table 1). The most important negatively charged residue was E1287, as peptide E1287Q had a 9.3- fold loss in binding affinity relative to FYCO1. D1281N and E1286Q peptides had a moderate loss in affinity, 3.8-fold and 2.6- fold less than FYCO1, respectively.

After demonstrating the relative contributions of the terminal residues and negative charges, we next investigated the hydrophobic residues. The FYCO1 peptide binds LC3B in an extended conformation, with F1280 and I1283 binding separate, conserved hydrophobic pockets on LC3B (HP1 and HP2, Fig. 1c).[59] Based on the crystal structure, we observed that HP1 (the binding pocket for F1280) may be able to accommodate a larger hydrophobic side chain, so we prepared analogs with either 1-naphthylalanine or 2-naphthylalanine in this position (F1280Nap1 and F1280Nap2). Both substitutions improved binding, each by roughly 2-fold (Table 1). The crystal structure also suggested that HP2 (the binding pocket for I1283) might accommodate larger side chains, but substituting I1283 with either a phenylalanine or a 2-naphthylalanine resulted in ligands with poorer LC3B affinity (20- and 9-fold losses in affinity, respectively). These data support that HP1 of LC3B, but not HP2, is amenable to binding larger side chains.

In the crystal structure, L1288 and I1291 of FYCO1 bind a shallow hydrophobic groove adjacent to HP2 (Fig. 1c). In each of these positions, we explored several side chains that might enhance hydrophobic interactions. Substituting I1291 with a tert-butylalanine or phenylalanine resulted in 1.5-fold or 2.5-fold poorer affinity, respectively. Substituting L1288 with the larger aliphatic residue 5,5-dimethyl-norleucine led to a 2-fold loss in affinity, but substituting L1288 with a tert-butylalanine (peptide L1288tbA) resulted in a very slight improvement in affinity (Kd value of 0.25 μM). These data suggest that the shallow groove may only accommodate moderately-sized aliphatic residues, but that exploration of artificial aliphatic side chains could lead to further improvements in affinity.

Another feature of the crystal structure is the close proximity to the binding site of several negatively charged LC3B residues. Specifically, the N-terminus of the bound FYCO1 peptide is positioned near LC3B residues D48, E18 and D19. Thus, we sought to introduce new electrostatic interactions through the incorporation of one or two arginine residues near the N-terminus of FYCO1. Substitution of solvent-oriented A1278 with D-arginine, which was selected to position the side chain near LC3B residues E18 and D19, produced a peptide with 3-fold poorer binding affinity (Table 1). Interestingly, addition of one arginine to the N-terminus of the FYCO1 peptide improved binding affinity (peptide R-FYCO1, with a Kd value of 0.2 μM), but incorporation of two arginines demonstrated no benefit (peptide RR-FYCO1, with a Kd value of 0.33 μM).

To this point, three individual substitutions had resulted in a gain in affinity (F1280Nap2, L1288tbA, and R-FYCO1; see Table 1). Combining these substitutions, we prepared and tested peptide Comb1 and measured a Kd for LC3B of 0.12 μM, representing a 2.4-fold improvement over the parent peptide.

Having elucidated broad structure-activity relationships for the FYCO1 peptide, we next sought to introduce structure-stabilizing covalent cross-links. Side-chain-to-side-chain covalent cross-links, or “staples”, have most often been applied to alpha-helical peptides. In many cases, stapled alpha-helices have a greater extent of secondary structure, improved affinity and selectivity, improved cell penetration, and increased resistance to biological degradation.[72,73] Applying stapling strategies to non-helical peptides is significantly more challenging, but we and others have applied “diversity-oriented stapling” methods to improve pharmacological properties of non-helical peptides.[60–68] These approaches do not assume a specific secondary structure, and thus are applicable to peptides that bind their targets in extended conformations such as FYCO1.

As described in previous work, we used solution dithiol bis-alkylation reactions for diversity-oriented stapling.[66,67,74] Before we could apply this strategy to the FYCO1 peptide, we had to substitute the native cysteine C1289. The C1289S analog had very similar binding affinity to the parent FYCO1 peptide (Kd value of 0.33 versus 0.29 μM, Table 2). Inspecting the crystal structure of the LC3B-bound FYCO1 peptide, we observed that an (i,i+3) staple between positions 1279 and 1282 or an (i,i+5) staple between positions 1279 and 1284 could potentially accommodate a thioether staple (Fig. 1d). We prepared analogs of FYCO1 with double substitutions of cysteine at V1279 and I1282, cysteine at V1279 and T1284, or homocysteine at V1279 and T1284 (to help bridge the longer distance), and cross-linked them with ortho-, meta-, or para-dibromoxylene as described.[66,67,74] In this manner, we produced a panel of eight uniquely constrained cyclic peptides (Table 2). All the (i,i+3) stapled peptides (C1282-o, C1282-m, and C1282-p) were poor LC3B ligands, with over a 30-fold loss in binding affinity compared to FYCO1. Both of the (i,i+5) stapled peptides that incorporated cysteines (peptides C1284-m and C1284-p) were similarly poor LC3B ligands. However, peptides that used homocysteines for the (i,i+5) staple had somewhat better affinity. The highest-affinity stapled peptide of this series, hC1284-m, had a 9-fold loss in affinity for LC3B compared to FYCO1 (Kd value of 2.5 μM).

Table 2.

Binding affinities for conformationally constrained FYCO1-derived peptides with LC3B protein. BLI and curve fitting were performed as described in Figure 2 and in Methods. Average Kd values and standard errors of the mean (Tables 1 and 2) were calculated from the individual curve fits of three independent replicates (Tables S2–4). 2 denotes 2-naphthylalanine, denotes tert-butylalanine, and C denotes homocysteine. Stapled peptides have their two cysteines or homocysteines bis-alkylated by an ortho-, meta- or para-dibromomethylbenzene, as indicated. All peptides have a C-terminal amide group and an N-terminal biotin separated from the peptide by two beta-alanine residues. ND denotes no binding affinity detected up to 20 μM LC3B protein.

| Name | Sequence | Kd (μM) | Std Err (μM) | Fold change from FYCO1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FYCO1 | DDAVFDIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.29 | 0.01 | 1.0 |

| C1289S | DDAVFDIITDEELSQIQEW | 0.33 | 0.03 | 1.1 |

| (i,i+3) Conformational Constraint | ||||

| C1282-o | DDACFDCITDEELSQIQEW (ortho) | ND | ND | ND |

| C1282-m | DDACFDCITDEELSQIQEW (meta) | 8.3 | 0.7 | 29 |

| C1282-p | DDACFDCITDEELSQIQEW (para) | 10.5 | 1.7 | 36 |

| (i,i+5) Conformational Constraint | ||||

| C1284-m | DDACFDIICDEELSQIQEW (meta) | 6.3 | 0.3 | 22 |

| C1284-p | DDACFDIICDEELSQIQEW (para) | 8.7 | 1.8 | 30 |

| hC1284-o | DDACFDIICDEELSQIQEW (ortho) | 4.5 | 0.8 | 16 |

| hC1284-m | DDACFDIICDEELSQIQEW (meta) | 2.5 | 0.1 | 8.6 |

| hC1284-p | DDACFDIICDEELSQIQEW (para) | 3.1 | 0.4 | 11 |

| Optimized Combination | ||||

| Comb2 | RDDAC2DIICDEEαSQIQEW (meta) | 0.26 | 0.01 | 0.90 |

Finally, we combined the three most beneficial individual substitutions (F1280Nap2, L1288tbA, and R-FYCO1) with the best-performing staple from peptide hC1284-m. Unexpectedly, this stapled peptide (Comb2) had a Kd of 0.26 μM, similar to the parent peptide FYCO1 and only 2.2-fold poorer than the optimized linear peptide Comb1 (Table 2).

Comb1 and Comb2 have many alterations to the electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions involved in LC3B binding. We next examined whether these changes altered the selectivity of these peptides for LC3B over GABARAP. Using a BLI assay for GABARAP binding, we determined that Comb1 and Comb2 bound to GABARAP with Kd values of 0.67 and 1.4 μM, respectively (Table 3). Overall, the parent FYCO1 peptide binds LC3B with 5.1-fold selectivity over GABARAP, and Comb1 and Comb2 bind LC3B over GABARAP with 5.6-fold and 5.4-fold selectivity, respectively. These data demonstrate that LC3B selectivity was retained with the incorporation of multiple substitutions and stapling.

Table 3.

Binding affinities for FYCO1-derived peptides with GABARAP protein, and selectivities for LC3B over GABARAP. BLI and curve fitting were performed as described in Figure 2 and in Methods. Average Kd values and standard errors of the mean (Tables 1–3) were calculated from the individual curve fits of three independent replicates (Tables S2–S7). 2 denotes 2-naphthylalanine, denotes tert-butylalanine, and C denotes homocysteine. Comb2 has its homocysteines bis-alkylated by a meta-dibromomethylbenzene. All peptides have a C-terminal amide group and an N-terminal biotin separated from the peptide by two beta-alanine residues.

| Name | Sequence | Kd for LC3B (μM) | Std Err (μM) | Kd for GABARAP (μM) | Std Err (μM) | LC3B selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K1 | DATYTWEHLAWP | 18.7 | 1.9 | 0.39 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| FYCO1 | DDAVFDIITDEELCQIQEW | 0.29 | 0.01 | 1.4 | 0.02 | 5.1 |

| Comb1 | RDDAV2DIITDEEαCQIQEW | 0.12 | 0.004 | 0.67 | 0.08 | 5.6 |

| Comb2 | RDDAC2DIICDEEαSQIQEW (meta) | 0.26 | 0.01 | 1.4 | 0.03 | 5.4 |

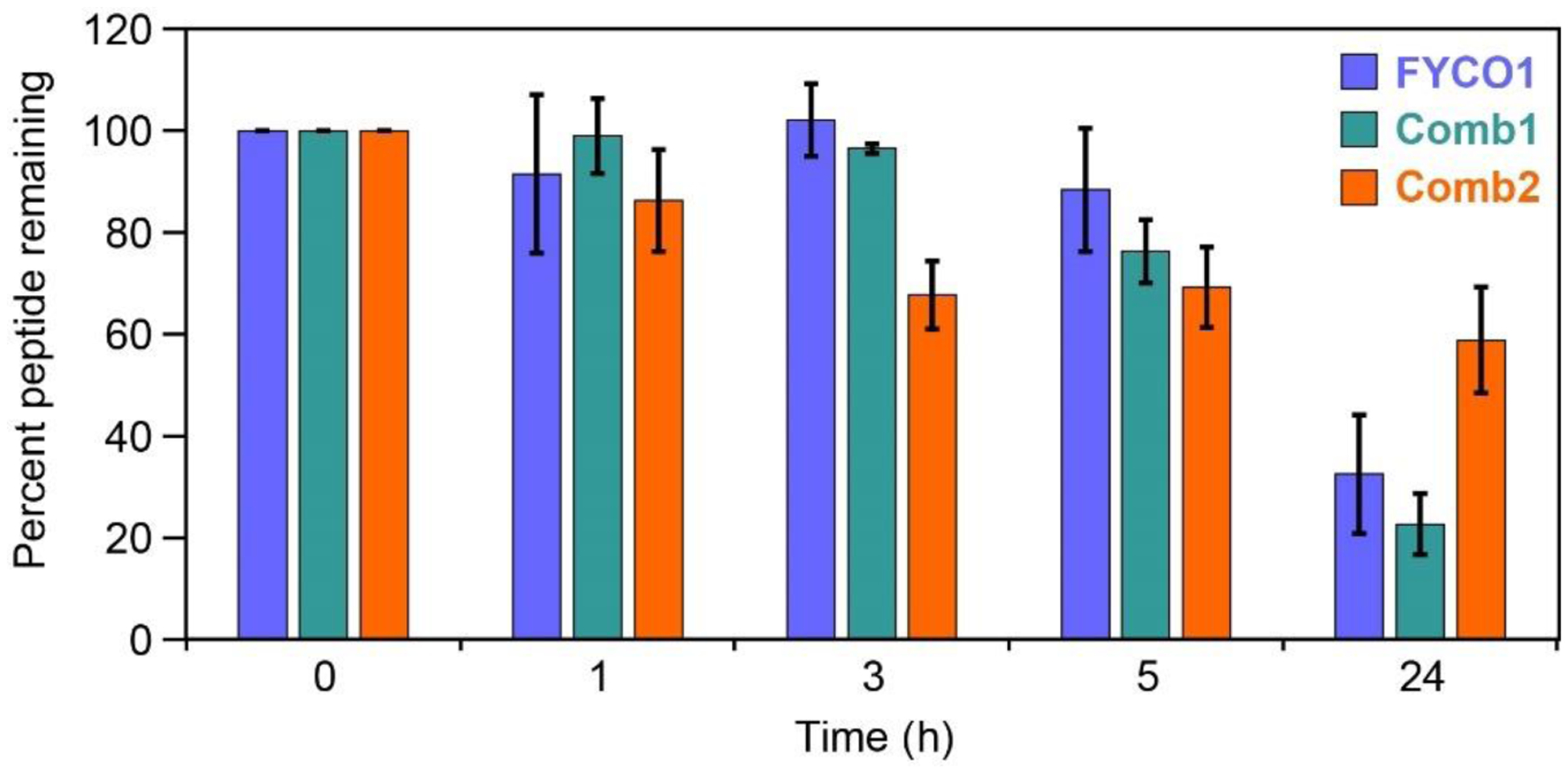

Often, introducing artificial amino acids and conformational constraints within a peptide increases its proteolytic stability. To assess the proteolytic stability of LC3B-binding peptides, we employed a rigorous cell lysate stability assay recently described for stapled alpha-helical peptides.[75] We incubated peptides for various times between 1 and 24 hours in a HeLa cell lysate, then precipitated proteins in ice cold methanol and analyzed the supernatants by analytical HPLC (Fig. 3, Fig. S4). Surprisingly, the parent FYCO1 peptide showed little degradation for up to three hours, but by 24 hours only a third of the peptide was remaining. The optimized linear peptide, Comb1, had similar results. The optimized stapled peptide, Comb2, showed an unusual proteolytic stability profile. At 3 hours, there was less Comb2 remaining compared to FYCO1, but after 24 hours there was roughly double the amount of Comb2 remaining compared to FYCO1 (59% of intact Comb2 remaining after 24 hours). Despite the unusual result at 3 hours, we concluded that Comb2 was more resistant to degradation than FYCO1 and Comb1 over the long-term.

Figure 3.

Proteolytic stability of peptides in HeLa cell lysates. Peptides FYCO1, Comb1 and Comb2 were incubated for selected time points in HeLa cell lysate at 37 °C.[75] Samples were quenched in methanol and supernatant analyzed by analytical HPLC. Areas under each peptide chromatogram peak were normalized to the area under the zero timepoint chromatogram peak. HPLC chromatograms are shown in Fig S4. Average values and standard errors of the mean were calculated from four independent replicates (representative primary data shown in Fig. S4).

Discussion

Many proteins have been shown to bind LC3B through their LIR motifs using co-immunoprecipitation or similar techniques. However, only a few prior studies have characterized LIR motif-LC3B binding quantitatively, and structure-activity relationships for this interaction are limited. Several prior papers showed that the LIR motif from FYCO1 binds LC3A/B selectively over LC3C and GABARAPs,[49,58,59] with varying degrees of selectivity.[69,76] Our work supports that the FYCO1 LIR motif is indeed moderately selective (roughly 5-fold) for LC3B over GABARAP. Additionally, our results extend prior understanding that negatively charged residues are important for LC3B binding,[58,59] showing that the most important contributor to LC3B binding, outside of the core LIR motif, is the negative charge at E1287. The negative charge at D1281 and polar interactions of the N-terminus of FYCO1 also play moderately important roles in LC3B binding.

Comparisons among hydrophobic residues in native LIR motifs have been performed,[49,57,58,71] but this work extends this understanding using artificial aliphatic and aromatic amino acids. Overall, in the context of the FYCO1-LC3B interaction, we found that targeting HP1 with larger hydrophobic amino acids improved binding while HP2 did not tolerate larger substitutions. Given the limited number of artificial amino acids we have tested so far, it is highly likely that further substitution of F1280 will produce analogs with even better affinity. Because the F1280Nap2 substitution and other modifications were synergistic with the (i,i+5) staple, these and other continued efforts should be done in the context of both linear and stapled peptides.

Optimized FYCO1 LIR peptides maintain moderate selectivity for LC3B over GABARAP. Recent work demonstrated that the residues C-terminal to the core LIR motif (here, residues 1285–1293) can greatly impact GABARAP/LC3B selectivity.[69] It is therefore likely that this region of the peptide serves to preserve selectivity even in the presence of the N-terminal staple. While LIR-based peptide inhibitors of LC3B proteins with higher affinity were recently reported,[77] these were not selective for LC3B over GABARAP. Thus, to the best of our knowledge, Comb1 and Comb2 represent the highest-affinity Atg8 ligands that maintain LC3B selectivity over GABARAP.

This work also introduces an (i,i+5) stapled peptide, Comb2, with binding affinity and selectivity similar to the native FYCO1. Because peptide stapling has focused primarily on helical peptides which require stapling at (i,i+3), (i,i+4) or (i,i+7) relative positions, this application of an (i,i+5) staple is highly unusual. One of the primary benefits of peptide stapling is improved stability in biological environments.[72,73] We tested this potential benefit in the context of the (i,i+5) stapled peptide Comb2 using a rigorous test of proteolytic stability.[75] We observed a roughly 2-fold reduction in peptide degradation over 24 hours compared to the Comb1 peptide, which allows us to attribute this modest benefit to the staple itself. Notably, this is less of an effect than is typically observed for stapled alpha-helices.[72] This may indicate that the extended structure imposed by the (i,i+5) staple offers less proteolytic resistance than a cooperatively folded alpha-helix. This explanation may also account for the unusual time dependence of proteolytic degradation observed for Comb2. Further exploration of non-helical stapled peptides will be required to more fully understand how staples affect structure and proteolytic degradation for non-helical peptides.

Conclusions

Comb1 and Comb2 are potent LC3-inhibiting peptides for assays using recombinant proteins, and for assays using cell lysates. Additional work will be required to translate LC3B-selective peptides into useful cellular probes. The most significant hurdle is cytosolic penetration.[78] While this work highlighted numerous negative charges that contribute only moderately to affinity, it remains clear that negative charge is required for high-affinity binding to LC3B. Anionic peptides can be difficult to deliver to the interior of cells, even as fusions to cell-penetrating peptides. Advanced cell-penetrating peptides have demonstrated the ability to deliver anionic cargo, and these may provide a better means of efficiently delivering LIR motif peptides to the cytosol.[79–81] Future application of a wider diversity of stapling strategies and stapling positions may uncover new synergies that further optimize LC3B affinity, selectivity, proteolytic stability, and cytosolic penetration. The present work will directly inform those efforts, providing valuable tools for research into the basic mechanisms of autophagy and the links between autophagy and cancer.

Methods

Peptide Synthesis

All peptides were synthesized via standard Fmoc solid-phase peptide synthesis on an automated Tribute Peptide Synthesizer (Gyros Protein Technologies). Peptides were synthesized on Rink amide resin (substitution 0.55 mmol/g) with deprotection in 20% piperidine in DMF, and coupling with 5 equiv. each of amino acid, HBTU, and HOBt, and 10 equiv. of DIPEA. DMF washes were performed between each step. To prepare biotinylated peptides, the N-terminus was deprotected in 20% piperidine in DMF followed by overnight incubation in 5 equiv. of biotin-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (Millipore Sigma) and 10 equiv. DIPEA in DMF. To prepare fluorescein-labeled peptides, 5 equiv. of 5,6-carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were coupled overnight with 10 equiv. DIPEA in DMF. All peptides included a C-terminal tryptophan for spectrophotometric concentration determination, and two beta-alanine residues between the N-terminus of the FYCO1-derived sequence and the fluorescein or biotin. All peptides were globally deprotected and cleaved using a TFA cleavage cocktail (95:2:2:1, TFA:H2O:EDT:TIPS) for 3 hours. Following cleavage, peptides were precipitated in cold diethyl ether , pelleted, and washed with additional diethyl ether. Peptides were then dried and resuspended in 50:50 water:acetonitrile for reverse-phase HPLC purification on a preparative-scale C8 column using a gradient of 5 – 100% acetonitrile in 30 min. Peptides were purified to at least 95% purity as determined by analytical HPLC. Masses were determined using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry with a matrix of 10 mg/mL α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamate in 50:50 water:acetonitrile with 0.1% TFA. Observed masses of final products are given in supplemental figure S1. Following purification, peptides were lyophilized and resuspended in DMSO for working solutions, which were quantified based on absorbance at 280 nm (Thermo Scientific Nanodrop 1000).

Protein Expression

LC3B protein was expressed and purified as described.[82] BL21 E. coli were transformed with a pET-15b expression plasmid for full-length LC3B (codons 1–125). Transfected cells were grown on ampicillin agar plates and colonies were selected and grown in LB culture medium. At an optical density of 0.6 to 0.8, 1 mM IPTG was added and cells were incubated for 3 hours at 37 °C. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in a lysis buffer of 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 0.2% lysozyme, 1 protease inhibitor cocktail pellet (Roche), and 2.5 U/mL universal nuclease (Pierce). Resuspended cells were sonicated and lysed, and the lysate was centrifuged to pellet debris. The protein was purified from clarified lysate using Ni-NTA resin by incubating protein with resin for 45 min at 4 °C, rinsing with wash buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole), and then eluting in 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole at 4°C. The eluate was further purified by size exclusion chromatography using an automated FPLC system (AKTA, GE) on a Superdex S75 analytical column in 25 mM Tris pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 0.05% 2-mercaptoethanol. Protein fractions were analyzed via SDS-PAGE, and pure fractions were pooled together. Concentration of protein was quantified via absorbance at 280 nm and confirmed via BCA assay. Protein was stored in frozen aliquots at −80°C.

For GABARAP protein expression, BL21 E. coli were transformed with a pGex-4T-2 expression plasmid for full-length GABARAP (codons 1–117).[83] Expression and lysis was performed in the same manner as with LC3B protein. For purification, glutathione resin was incubated with clarified lysate for 45 min at 4 °C before rinsing with PBS. The GST tag was then removed overnight with thrombin protease treatment at 4 °C and the cleaved protein was eluted from the column. Protein fractions were analyzed via SDS-PAGE and pure fractions were pooled. Concentrations were quantified via absorbance at 280 nm (Thermo Scientific Nanodrop 1000) and confirmed via BCA assay. Protein was stored in frozen aliquots at −80 °C.

Biolayer Interferometry

BLI assays were performed on an Octet K2 System (Forté Bio). Biotinylated peptides and proteins were diluted to 0.5 μg/mL in assay buffer (PBS pH 7.4, 0.02% Tween-20, 0.5 mg/mL BSA) at a final volume of 200 μL in a flat, black 96-well polypropylene plate (Greiner Bio-One). Biotinylated peptides were loaded onto streptavidin-coated tips, tips were washed, and then 200 seconds of association of LC3B or GABARAP protein was measured. Following association of the protein with the immobilized peptide, dissociation of the protein was measured for an additional 200 seconds. Assays were run at 30 °C with shaking at 1000 rpm. Protein concentrations were varied in order to achieve a response of 0.3 nm association or higher, with protein concentration not exceeding 20 μM for LC3B or 4 μM for GABARAP. Curve fitting was generated using a 1:1 fitting model by Octet DataAnalysis software (FortéBio). Kobs values were extracted from these curve fits, and Kobs was plotted versus protein concentration. The slope of this line provided the association rate (Kon). The dissociation rate was extracted from the 1:1 curve fit to the dissociation data. Finally, Kd values were calculated by dividing the Koff by the Kon. All peptides were tested in three separate replicates and average Kd, Kon¸ and Koff values and standard error were calculated (see Tables S2–7 in Supplementary Information).

Fluorescence Polarization Assays

Fluorescence polarization assays were performed as described.28 Dye-labeled peptide was mixed at a final concentration of 10 nM with a serial dilution of LC3B or GABARAP protein in a final reaction volume of 20 μL in a black, flat-bottomed 384-well polypropylene plate (Greiner Bio-One). The buffer composition was PBS pH 7.3 with 0.1% Tween-20. The plate was incubated in the dark for 1 hr at room temperature, then read at 494 nm excitation and 519 nm emission. Kd values were obtained from curve fits using KaleidaGraph software as described.44

Lysate Stability Assays

For lysate stability assays, HeLa cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS, pelleted, and treated with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris, 250 mM NaCl, 0.5% IGEPAL CA-630 detergent, pH 8.0) on ice for 15 min. Then, lysates were centrifuged for 10 min at 4 °C at 14,800 rpm and the clarified lysate was collected. Peptides were added to the lysate to a concentration of 150 μM and were incubated at 37 °C. Aliquots of 40 μL were taken at each time point and quenched in 160 μL of ice-cold methanol. Samples were spun down for 10 min at 14,800 rpm prior to analysis via reverse-phase analytical HPLC on a C18 column. Chromatogram peaks were integrated to measure amount of peptide remaining at each time point. Peak volumes for each timepoint were normalized to the zero-hour timepoint to determine percentage of peptide remaining. Data presented is the average of four biological replicates performed with different lysates on different days.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein Individual Predoctoral NRSA Fellowship F30CA220678 (NCI, NIH) and by NIH GM125856.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Works Cited

- [1].Levine B, Kroemer G, Cell 2008, 132, 27–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ, Nature 2008, 451, 1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Levine B, Kroemer G, Cell 2019, 176, 11–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Levy JMM, Towers CG, Thorburn A, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2017, 17, 528–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rubinsztein DC, Codogno P, Levine B, Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 2012, 11, 709–U84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mathew R, Karantza-Wadsworth V, White E, Nat. Rev. Cancer 2007, 7, 961–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vega-Rubín-de-Celis S, Zou Z, Fernández ÁF, Ci B, Kim M, Xiao G, Xie Y, Levine B, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci 2018, 115, 4176–4181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Fernández ÁF, Sebti S, Wei Y, Zou Z, Shi M, McMillan KL, He C, Ting T, Liu Y, Chiang W-C, et al. , Nature 2018, 558, 136–140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Qu X, Yu J, Bhagat G, Furuya N, Hibshoosh H, Troxel A, Rosen J, Eskelinen E-L, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, et al. , J. Clin. Invest 2003, 112, 1809–1820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Guo JY, Karsli-Uzunbas G, Mathew R, Aisner SC, Kamphorst JJ, Strohecker AM, Chen G, Price S, Lu W, Teng X, et al. , Genes Dev. 2013, 27, 1447–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xie X, Koh JY, Price S, White E, Mehnert JM, Cancer Discov. 2015, 5, 410–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gammoh N, Fraser J, Puente C, Syred HM, Kang H, Ozawa T, Lam D, Acosta JC, Finch AJ, Holland E, et al. , Autophagy 2016, 12, 1431–1439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Peng Y-F, Shi Y-H, Ding Z-B, Ke A-W, Gu C-Y, Hui B, Zhou J, Qiu S-J, Dai Z, Fan J, Autophagy 2013, 9, 2056–2068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mowers EE, Sharifi MN, Macleod KF, Oncogene 2017, 36, 1619–1630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Katheder NS, Khezri R, O’Farrell F, Schultz SW, Jain A, Rahman MM, Schink KO, Theodossiou TA, Johansen T, Juhász G, et al. , Nature 2017, 541, 417–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Piya S, Kornblau SM, Ruvolo VR, Mu H, Ruvolo PP, McQueen T, Davis RE, Hail N, Kantarjian H, Andreeff M, et al. , Blood 2016, 128, 1260–1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Briceño E, Reyes S, Sotelo J, Neurosurg. Focus 2003, 14, e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Sotelo J, Briceño E, López-González MA, Ann. Intern. Med 2006, 144, 337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Boone BA, Bahary N, Zureikat AH, Moser AJ, Normolle DP, Wu W-C, Singhi AD, Bao P, Bartlett DL, Liotta LA, et al. , Ann. Surg. Oncol 2015, 22, 4402–4410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mauthe M, Orhon I, Rocchi C, Zhou X, Luhr M, Hijlkema K-J, Coppes RP, Engedal N, Mari M, Reggiori F, Autophagy 2018, 14, 1435–1455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Pasquier B, Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2016, 73, 985–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].McAfee Q, Zhang Z, Samanta A, Levi SM, Ma X-H, Piao S, Lynch JP, Uehara T, Sepulveda AR, Davis LE, et al. , Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2012, 109, 8253–8258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rebecca VW, Nicastri MC, McLaughlin N, Fennelly C, McAfee Q, Ronghe A, Nofal M, Lim C-Y, Witze E, Chude CI, et al. , Cancer Discov. 2017, 7, 1266–1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rebecca VW, Nicastri MC, Fennelly C, Chude CI, Barber-Rotenberg JS, Ronghe A, McAfee Q, McLaughlin NP, Zhang G, Goldman AR, et al. , Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 220–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Goodall ML, Wang T, Martin KR, Kortus MG, Kauffman AL, Trent JM, Gately S, MacKeigan JP, Autophagy 2014, 10, 1120–1136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Noman MZ, Parpal S, Moer KV, Xiao M, Yu Y, Viklund J, Milito AD, Hasmim M, Andersson M, Amaravadi RK, et al. , Sci. Adv 2020, 6, eaax7881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Egan DF, Chun MGH, Vamos M, Zou H, Rong J, Miller CJ, Lou HJ, Raveendra-Panickar D, Yang C-C, Sheffler DJ, et al. , Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 285–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Petherick KJ, Conway OJL, Mpamhanga C, Osborne SA, Kamal A, Saxty B, Ganley IG, J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 11376–11383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ronan B, Flamand O, Vescovi L, Dureuil C, Durand L, Fassy F, Bachelot M-F, Lamberton A, Mathieu M, Bertrand T, et al. , Nat. Chem. Biol 2014, 10, 1013–1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Martin KR, Celano SL, Solitro AR, Gunaydin H, Scott M, O’Hagan RC, Shumway SD, Fuller P, MacKeigan JP, iScience 2018, 8, 74–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Dyczynski M, Yu Y, Otrocka M, Parpal S, Braga T, Henley AB, Zazzi H, Lerner M, Wennerberg K, Viklund J, et al. , Cancer Lett. 2018, 435, 32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Bago R, Malik N, Munson MJ, Prescott AR, Davies P, Sommer E, Shpiro N, Ward R, Cross D, Ganley IG, et al. , Biochem. J 2014, 463, 413–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Dowdle WE, Nyfeler B, Nagel J, Elling RA, Liu S, Triantafellow E, Menon S, Wang Z, Honda A, Pardee G, et al. , Nat. Cell Biol 2014, 16, 1069–1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lazarus MB, Novotny CJ, Shokat KM, ACS Chem. Biol 2015, 10, 257–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Wood SD, Grant W, Adrados I, Choi JY, Alburger JM, Duckett DR, Roush WR, ACS Med. Chem. Lett 2017, 8, 1258–1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Xue S-T, Li K, Gao Y, Zhao L-Y, Gao Y, Yi H, Jiang J-D, Li Z-R, Autophagy n.d., DOI 10.1080/15548627.2019.1709762. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Tang F, Hu P, Yang Z, Xue C, Gong J, Sun S, Shi L, Zhang S, Li Z, Yang C, et al. , Oncol. Rep 2017, 37, 3449–3458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zahedi S, Fitzwalter BE, Morin A, Grob S, Desmarais M, Nellan A, Green AL, Vibhakar R, Hankinson TC, Foreman NK, et al. , Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Janser FA, Adams O, Bütler V, Schläfli AM, Dislich B, Seiler CA, Kröll D, Langer R, Tschan MP, Int. J. Mol. Sci 2018, 19, 3069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Schluetermann D, Skowron MA, Berleth N, Boehler P, Deitersen J, Stuhldreier F, Wallot-Hieke N, Wu W, Peter C, Hoffmann MJ, et al. , Urol. Oncol.-Semin. Orig. Investig 2018, 36, 160.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Bryant KL, Stalnecker CA, Zeitouni D, Klomp JE, Peng S, Tikunov AP, Gunda V, Pierobon M, Waters AM, George SD, et al. , Nat. Med 2019, 25, 628-+. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Follo C, Cheng Y, Richards WG, Bueno R, Broaddus VC, Mol. Carcinog 2018, 57, 319–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Qiu L, Zhou G, Cao S, Life Sci. 2020, 243, 117234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Dower CM, Bhat N, Gebru MT, Chen L, Wills CA, Miller BA, Wang H-G, Mol. Cancer Ther 2018, 17, 2365–2376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Lu J, Zhu L, Zheng L, Cui Q, Zhu H, Zhao H, Shen Z, Dong H, Chen S, Wu W, et al. , Ebiomedicine 2018, 34, 85–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Mikhaylova O, Stratton Y, Hall D, Kellner E, Ehmer B, Drew AF, Gallo CA, Plas DR, Biesiada J, Meller J, et al. , Cancer Cell 2012, 21, 532–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Klebig C, Seitz S, Arnold W, Deutschmann N, Pacyna-Gengelbach M, Scherneck S, Petersen I, Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 394–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Genau HM, Huber J, Baschieri F, Akutsu M, Dötsch V, Farhan H, Rogov V, Behrends C, Mol. Cell 2015, 57, 995–1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Alemu EA, Lamark T, Torgersen KM, Birgisdottir AB, Larsen KB, Jain A, Olsvik H, Øvervatn A, Kirkin V, Johansen T, J. Biol. Chem 2012, 287, 39275–39290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Grunwald DS, Otto NM, Park J-M, Song D, Kim D-H, Autophagy 2019, 0, 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Satoo K, Noda NN, Kumeta H, Fujioka Y, Mizushima N, Ohsumi Y, Inagaki F, EMBO J. 2009, 28, 1341–1350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun J-A, Outzen H, Øvervatn A, Bjørkøy G, Johansen T, J. Biol. Chem 2007, 282, 24131–24145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Pankiv S, Alemu EA, Brech A, Bruun J-A, Lamark T, Overvatn A, Bjørkøy G, Johansen T, J. Cell Biol 2010, 188, 253–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Padman BS, Nguyen TN, Uoselis L, Skulsuppaisarn M, Nguyen LK, Lazarou M, Nat. Commun 2019, 10, DOI 10.1038/s41467-019-08335-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].McEwan DG, Popovic D, Gubas A, Terawaki S, Suzuki H, Stadel D, Coxon FP, Miranda de Stegmann D, Bhogaraju S, Maddi K, et al. , Mol. Cell 2015, 57, 39–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Nguyen TN, Padman BS, Usher J, Oorschot V, Ramm G, Lazarou M, J. Cell Biol 2016, 215, 857–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Olsvik HL, Lamark T, Takagi K, Larsen KB, Evjen G, Øvervatn A, Mizushima T, Johansen T, J. Biol. Chem 2015, 290, 29361–29374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Atkinson JM, Ye Y, Gebru MT, Liu Q, Zhou S, Young MM, Takahashi Y, Lin Q, Tian F, Wang H-G, J. Biol. Chem 2019, 294, 14033–14042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Cheng X, Wang Y, Gong Y, Li F, Guo Y, Hu S, Liu J, Pan L, Autophagy 2016, 12, 1330–1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Siegert TR, Bird MJ, Makwana KM, Kritzer JA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2016, 138, 12876–12884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Peraro L, Zou Z, Makwana KM, Cummings AE, Ball HL, Yu H, Lin Y-S, Levine B, Kritzer JA, J. Am. Chem. Soc 2017, 139, 7792–7802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Kamens AJ, Mientkiewicz KM, Eisert RJ, Walz JA, Mace CR, Kritzer JA, Bioorg. Med. Chem 2018, 26, 1206–1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Tran PT, Larsen CØ, Røndbjerg T, De Foresta M, Kunze MBA, Marek A, Løper JH, Boyhus L-E, Knuhtsen A, Lindorff‐Larsen K, et al. , Chem. – Eur. J 2017, 23, 3490–3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Wu Y, Kaur A, Fowler E, Wiedmann MM, Young R, Galloway WRJD, Olsen L, Sore HF, Chattopadhyay A, Kwan TT-L, et al. , ACS Chem. Biol 2019, 14, 526–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Mortensen KT, Osberger TJ, King TA, Sore HF, Spring DR, Chem. Rev 2019, 119, 10288–10317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Peraro L, Siegert TR, Kritzer JA, in Methods Enzymol., Elsevier, 2016, pp. 303–332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Timmerman P, Beld J, Puijk WC, Meloen RH, Chembiochem Eur. J. Chem. Biol 2005, 6, 821–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Zou Y, Spokoyny AM, Zhang C, Simon MD, Yu H, Lin Y-S, Pentelute BL, Org. Biomol. Chem 2013, 12, 566–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Wirth M, Zhang W, Razi M, Nyoni L, Joshi D, O’Reilly N, Johansen T, Tooze SA, Mouilleron S, Nat. Commun 2019, 10, DOI 10.1038/s41467-019-10059-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Weiergräber OH, Stangler T, Thielmann Y, Mohrlüder J, Wiesehan K, Willbold D, J. Mol. Biol 2008, 381, 1320–1331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Birgisdottir ÅB, Lamark T, Johansen T, J. Cell Sci 2013, 126, 3237–3247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Walensky LD, Bird GH, J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 6275–6288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Verdine GL, Walensky LD, Clin. Cancer Res 2007, 13, 7264–7270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Heinis C, Rutherford T, Freund S, Winter G, Nat. Chem. Biol 2009, 5, 502–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Partridge AW, Kaan HYK, Juang Y-C, Sadruddin A, Lim S, Brown CJ, Ng S, Thean D, Ferrer F, Johannes C, et al. , Molecules 2019, 24, 2292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Rogov VV, Stolz A, Ravichandran AC, Rios‐Szwed DO, Suzuki H, Kniss A, Löhr F, Wakatsuki S, Dötsch V, Dikic I, et al. , EMBO Rep. 2017, 18, 1382–1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Li J, Zhu R, Chen K, Zheng H, Zhao H, Yuan C, Zhang H, Wang C, Zhang M, Nat. Chem. Biol 2018, 14, 778–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Peraro L, Kritzer JA, Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed 2018, 57, 11868–11881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Qian Z, Martyna A, Hard RL, Wang J, Appiah-Kubi G, Coss C, Phelps MA, Rossman JS, Pei D, Biochemistry 2016, 55, 2601–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Song J, Qian Z, Sahni A, Chen K, Pei D, ChemBioChem 2019, 20, 2085–2088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Wissner RF, Steinauer A, Knox SL, Thompson AD, Schepartz A, ACS Cent. Sci 2018, 4, 1379–1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Ma P, Schwarten M, Schneider L, Boeske A, Henke N, Lisak D, Weber S, Mohrlüder J, Stoldt M, Strodel B, et al. , J. Biol. Chem 2013, 288, 37204–37215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Stangler T, Mayr LM, Dingley AJ, Luge C, Willbold D, Biomol J. NMR 2001, 21, 183–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.