Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative brain disorder associated with relentlessly progressive loss of of memory and cognitive impairment. AD pathology proceed for decades before cognitive deficits become clinically apparent, opening a window for preventative therapy. Imbalance of clearance and buildup of amyloid β and phosphorylated-Tau proteins in the central nervous system are believed to contribute to AD pathogenesis. However, multiple clinical trials of treatments aimed at averting accumulation of these proteins have yielded little success and there is still no disease-modifying intervention. Here, we discuss current knowledge of AD pathology and treatment with an emphasis on emerging biomarkers and treatment strategies.

Keywords: Alzheimer Disease, Plaque, Amyloid, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Cognition, Biomedical Research

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive, irreversible disabling neurodegenerative disorder characterized by memory loss, cognitive dysfunction and behavioral changes (1-3). It is the leading cause of dementia, affecting approximately 46.8 million people globally (4-6.). At the molecular level, pathological changes in the brain that are hallmarks of AD include intracellular neurofibrillary tangles (NFTs) containing hyperphosphorylated tau protein and insoluble extracellular β-amyloid (Aβ) plaques (7, 8). Pathological changes in the brain precede clinical symptoms and, therefore, diagnosis, by decades (9-11). The debilitating effects of AD impose an enormous social, emotional and economic burden on patients and their families (6, 12). The etiology of AD remains unclear and despite research programs costing billions of dollars and numerous successful approaches in mouse models, at this time, there are no effective treatments for human AD (13-16). Mild symptomatic benefits are all that can be offered. This symposium will explore the underlying reasons for failure in developing effective drugs and suggest possible new directions to improve prognosis for this devastating disease.

APP Processing and Aβ Formation

The amyloid cascade hypothesis is a widely accepted model of AD pathogenesis that postulates an imbalance between production and clearance of the Aβ peptide leading to brain deposition of Aβ as the cause of AD (17, 18). Despite multiple failures, this hypothesis continues to drive the development of potential AD treatments (19, 20).

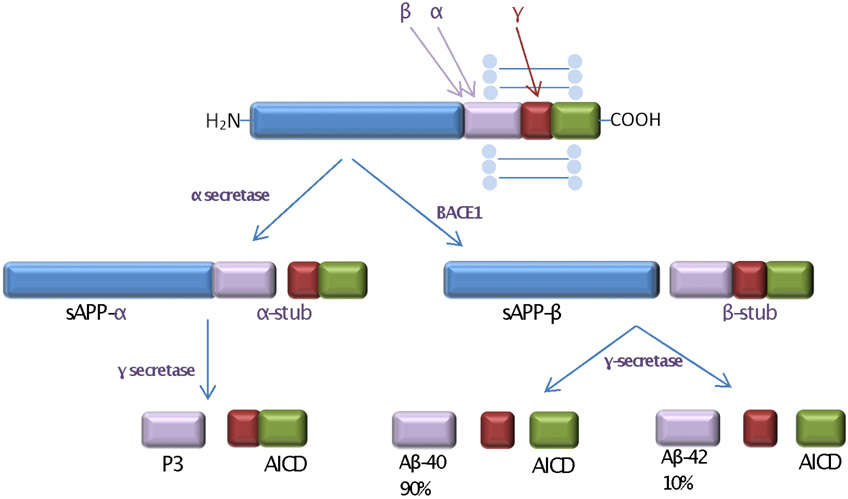

The proteolytic processing of APP determines whether Aβ will be generated (Figure 1). The three enzymes that control this process are α- secretase, β- secretase (β-site APP-cleaving enzyme, BACE1) and γ-secretase. APP can enter either an amyloidogenic or a non-amyloidogenic pathway, depending on which of these secretases act upon it. The amyloidogenic pathway begins with BACE1 releasing a soluble APP fragment (sAPP-β) and leaving in the membrane 99 amino acid C-terminal fragment (CTF-β) (21). This fragment is then cleaved by γ-secretase at slightly different positions, producing Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 as well as a cytoplasmic peptide, the APP intracellular domain (AICD). The non-amyloidogenic route starts with APP cleavage by α- secretase in the middle of the Aβ domain, freeing a soluble ectodomain (sAPP-α) and a membrane-bound C-terminal APP fragment of 83 amino acids (CTF-α). Further cleavage within the transmembrane domain by the γ-secretase complex yields the p3 peptide fragment and the AICD.

Figure 1. APP processing via non-amyloidogenic and amyloidogenic pathways.

The left side of the figure shows non-amyloid-forming reactions in which APP is cleaved by α-secretase to form sAPP-α, then by γ-secretase to yield P3 and AICD (amyloid intracellular domain). The right side of the figure shows amyloid-forming reactions in which APP is cleaved by BACE1 to form sAPP-β, then by γ-secretase to yield Aβ and AICD

Rodent Models

Transgenic mice overexpressing amyloid precursor protein (APP) have been used in myriad studies and have proven to be a valuable in vivo model, contributing tremendously to our understanding of AD pathophysiology (22-27). However, there is a disconnect between efficacy of treatment in rodent models and failure when attempts are made to translate to humans. In theory, Aβ removal or interference with Aβ aggregation will improve the signs and symptoms of AD. Unfortunately, this holds true in mice, but for reasons that we have to work out, it does not yield the same improvement in people (26, 28-30) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Problems with Current Strategies to Develop AD Treatment

| Mouse studies succeed, but human trials fail |

| Multiple attempts to use anti-amyloid antibodies by drug companies have been unsuccessful, and some have given up, rather than trying to go in another direction. |

| No good predictor of who will develop AD. Accurate prediction allows intervention before too much neuronal loss |

| No way to screen potential treatments for human efficacy other than 5 or 10 years of administering to humans or trying it on animals. |

| Lack of direct access to the neurons in the brain of the affected individual |

| No personalized approach or precision medicine as we see for many cancers |

Alzheimer Pathology and Imaging

The AD brain is notable for the presence of senile plaques and neurofibrillary tangles (31, 32). The plaques are composed primarily of fibrillar Aβ deposited extracellularly while the tangles are intracellular and consist of paired-helical filaments of hyperphosphorylated tau protein (33, 34). These pathological changes occur decades before initial clinical symptoms manifest (35, 36).

The American Colleges of Radiology and The American Colleges of Neurology each recommend structural imaging, such as noncontrast MRI in the evaluation of patients suspected of having AD (37, 38). Atrophy of the brain is a frequent finding on MRI in AD and correlates to the degree of cognitive impairment. Hippocampal atrophy is a validated AD biomarker (39). In general, the pattern of progression begins with early atrophy in the superior temporal region and the hippocampus, then subsequently in the amygdale and the remaining temporal regions and even later in the frontal association cortices (40, 41). Ventricular enlargement accompanies atrophy of the gyri and expanded sulci, indicating loss of both grey and white matter. As expected, a decrease in brain weight has been observed.

Aβ pathology can be imaged in human brain tissue in vivo by positron emission tomography (PET) using amyloid-β radiotracers (42, 43). The use of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) has allowed documentation of decreased glucose metabolism in the AD brain, generally occurring earliest in the posteromedial cortex and also in the temporal regions and correlating with neuronal or synaptic loss (44, 45).

Although imaging can show signs of incipient dementia before it becomes clinically overt, by the time imaging is abnormal, substantial neuronal loss has occurred (46). Further, progression from MCI to AD may be predicted with reasonable accuracy, but this does not lead to better outcome (47).

Current and Future Treatment: The Obstacles to Success

There is no disease modifying therapy for AD at this time (15, 48). Only modest symptomatic relief for between 6 and 18 months can be achieved, generally by using cholinesterase inhibitors to prevent degradation of acetylcholine and by using the glutamate receptor antagonist memantine to attenuate excitotoxicity (49). Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter and neuromodulator that plays a critical role in forming and retrieving memories and maintaining attention. Cholinesterase inhibitors are the first-line medications in the treatment of AD. They slow the degradation of acetylcholine in the synaptic cleft, thus treating AD by increasing cholinergic function in the brain (50). The currently available cholinesterase inhibitors most frequently prescribed are donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine (51, 52). Although cholinesterase inhibitors can slow symptoms of AD dementia, they do not alter the inevitable neurodegeneration and cognitive decline (53). The N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist memantine may delay cognitive decline, although not as effectively as cholinesterase inhibitors, and can be helpful in controlling agitation (54-56). Memantine, either as part of a multidrug regimen or by itself, is most clinically beneficial in people with moderate-to-severe AD (57). Memantine and anticholinesterase therapy are often combined, but it is not clear whether this is superior to the cholinesterase inhibitor alone (58).

In theory, Aβ removal or interference with Aβ aggregation will improve the signs and symptoms of AD (59, 60). Unfortunately, what is effective in mice, for reasons that are numerous and yet to be fully explained, does not translate to humans. Further, some anti-amyloid treatments have caused unacceptable side effects such as meningoencephalitis, brain edema, and brain microhemorrhage. The many failures in clinical trials of active and passive immunotherapies to remove Aβ have led Pfizer to close its neurology division and cease working on AD and Merck to suffer a major failure with verubecestat (61, 62).

Another impediment to designing treatments is the lack of early predictors of who will develop AD (Table 1). Identification of AD patients before they have undergone significant neurodegeneration becomes crucial if we are to preserve cognitive function (61). Current methods have limited accuracy in predicting progression to AD and the search for better biomarkers and imaging techniques is ongoing (63, 64). Currently, CSF biomarkers for AD that are measured in practice for some patients are Aβ42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau (65, 66).

Our lab and others are looking for early biomarkers. One possibility is micro(mi)RNAs, small endogenous non-protein-coding RNAs that influence the post-transcriptional regulation of gene expression and are involved in many neuronal processes (67, 68). A number of miRNAs show differential levels in the circulation and CSF in AD. These include miR-133b and miR-193a-3p which are downregulated in AD serum and miR-206 which is elevated in AD plasma (69-71). The predictive accuracy of any of these miRNAs has yet to be proven or brought into clinical use.

Not only can miRNAs serve as biomarkers, they may be targets for treatment because they can affect signaling pathways crucial to neuronal function (72). Circulating miRNAs are often carried in exosomes, small extracellular vesicles shed from all cells that contain cellular proteins, mRNA transcripts, miRNAs and lipids from their cell of origin (73). They are a fundamental mechanism of communication in the nervous system, allowing bidirectional cell signaling (74). The miRNAs within exosomes can transfer between neurons and microglia and can influence their phenotype. They can affect genes involved in Aβ generation (75). Extraction of exosomes that are shed from the neurons of the brain and CNS of humans with and without AD, may allow us to distinguish miRNAs from brain neurons that are altered by AD. This knowledge could then be used to identify signaling pathways relevant to nerve health and synaptic function that are modulated in AD and potentially to manipulate these in a beneficial direction to mitigate negative effects.

Our group is exploring a human cell culture model of AD that may circumvent or complement the need for rodents. It is not practical to do human brain biopsies and study brain cells in culture. If we could, that would be comparable to our approach to cancer (76). We can, however, approximate neurons from the brain using human induced pluripotent stem cells from patients clinically diagnosed with AD and differentiated to neural stem cells and then further differentiated to human cerebral cortical neurons (26, 77).

Neurons do not exist in isolation. To put a brain model together, microglia are essential because inflammation is undoubtedly part of the process of AD. With injury, the microglia proliferate and transform into active “brain macrophages,” also called reactive microglia. We know that amyloid and tau activate microglia (78, 79). In our model, we are looking at neurons and microglia together. There are differences in the mitochondrial bioenergetics in these AD-derived neurons and our unpublished results show that they respond differently than neurons from non-AD subjects to both direct exposure to high glucose and to conditioned medium from microglia exposed to high glucose. This study is in progress and as we and others continue to look beyond amyloid and tau, breakthroughs may be on the horizon.

Conclusions

AD is a common neurodegenerative disorder that leads inexorably to deterioration of cognitive functions, memory loss, motor impairment, and ultimately death. The need to develop new treatments is urgent and innovative thinking must prevail over repeated attempts to use the same approaches that have failed previously. In the interim there are fundamental steps to take now: encourage AD patients and healthy persons to eat a high quality diet, engage in regular physical activity, increase social connections and intellectual activities, avoid head trauma, and minimize heart disease risk factors: hypertension, obesity, high cholesterol, diabetes (keep A1C in normal range). These seem like very basic lifestyle behaviors that apply almost universally, but so many of us do not put in the effort to adhere to them.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by The Alzheimer's Foundation of America and The Herb and Evelyn Abrams Family Amyloid Research Fund. We thank Mr. Robert Buescher for his generous backing. We are grateful to Ms. Lynn Drucker for her tireless efforts and support.

References

- 1.Wisniewski T. Alzheimer's disease. 1st ed. Brisbane, Australia: Codon Publications; 2019. 10.15586/alzheimersdisease.2019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang Y, Mucke L. Alzheimer mechanisms and therapeutic strategies Cell 2012;148:1204–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabinovici GD. Late-onset Alzheimer Disease. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2019;25:14–33. doi: 10.1212/CON.0000000000000700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Du X, Wang X, Geng M. Alzheimer's disease hypothesis and related therapies Transl Neurodegener 2018;7:2. doi: 10.1186/s40035-018-0107-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez OL, Kuller LH. Epidemiology of aging and associated cognitive disorders: Prevalence and incidence of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. Handb Clin Neurol 2019;167:139–48. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-804766-8.00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Association As. 2019 Alzheimer's Disease Facts and Figures. Alzheimer's & Dementia. 2019;15(3):321–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hardy J. A hundred years of Alzheimer’s disease research. Neuron 2006;52:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingelsson M, Fukumoto H, Newell KL, et al. Early Abeta accumulation and progressive synaptic loss, gliosis, and tangle formation in AD brain. Neurology 2004;62:925–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, et al. Amyloid β deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:357–367. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70044-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubois B, Hampel H, Feldman HH, et al. Preclinical Alzheimer's disease: Definition, natural history, and diagnostic criteria. Alzheimers Dement 2016;12(3):292–323. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pletnikova O, Kageyama Y, Rudow G, et al. The spectrum of preclinical Alzheimer's disease pathology and its modulation by ApoE genotype. Neurobiol Aging 2018;71:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wimo A, Winblad B, Jonsson L. The worldwide societal costs of dementia: Estimates for 2009. Alzheimers Dement 2010;6:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheltens P, Blennow K, Breteler MM, et al. Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet 2016,388:505–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cummings J, Lee G, Aaron Ritter A, et al. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2019. Alzheimer Dement. 2019:5: 272–93. doi: 10.1016/j.trci.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wisniewski T, Drummond E. Future horizons in Alzheimer's disease research. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2019;168:223–41. doi: 10.1016/bs.pmbts.2019.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herline K, Drummond E, Wisniewski T. Recent advancements toward therapeutic vaccines against Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev Vaccines 2018;17(8):707–21. doi: 10.1080/14760584.2018.1500905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hardy J, Selkoe DJ. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002;297:353–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selkoe DJ, Hardy J. The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer's disease at 25 years. EMBO Mol Med 2016;8:595–608. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reiss AB, Arain HA, Stecker MM, et al. Amyloid Toxicity in Alzheimer’s Disease. Rev Neurosci 2018;29(6):613–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tolar M, Abushakra S, Sabbagh M. The path forward in Alzheimer's disease therapeutics: Reevaluating the amyloid cascade hypothesis. Alzheimers Dement. Published Online First: 6 November 2019. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.09.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussain I, Powell D, Howlett DR, et al. Identification of a novel aspartic protease (Asp 2) as beta-secretase. Mol Cell Neurosci 1999;14:419–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rivera-Escalera F, Pinney JJ, Owlett L, et al. IL-1β-driven amyloid plaque clearance is associated with an expansion of transcriptionally reprogrammed microglia. J Neuroinflammation 2019;16:261. doi: 10.1186/s12974-019-1645-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chakroborty S, Kim J, Schneider C, et al. Early presynaptic and postsynaptic calcium signaling abnormalities mask underlying synaptic depression in presymptomatic Alzheimer’s disease mice. J Neurosci 2012;32:8341–53. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0936-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dineley KT, Westerman M, Bui D, et al. Beta-amyloid activates the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade via hippocampal alpha7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors: In vitro and in vivo mechanisms related to Alzheimer's disease. J Neurosci 2001;21:4125–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-12-04125.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Radde R, Bolmont T, Kaeser SA, et al. Abeta42-driven cerebral amyloidosis in transgenic mice reveals early and robust pathology. EMBO Rep 2006;7:940–6. 10.1038/sj.embor.7400784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Drummond E, Wisniewski T. Alzheimer's disease: experimental models and reality. Acta Neuropathol 2017;133:155–75. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1662-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devinsky O, Boesch JM, Cerda-Gonzalez S, et al. A cross-species approach to disorders affecting brain and behaviour. Nat Rev Neurol 2018;14:677–86. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0074-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemere CA, Maron R, Spooner ET, et al. Nasal A beta treatment induces anti-A beta antibody production and decreases cerebral amyloid burden in PD-APP mice Ann NY Acad Sci 2000;920:328–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.King A The search for better animal models of Alzheimer's disease. Nature 2018;559:S13–15. doi: 10.1038/d41586-018-05722-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jankowsky JL, Zheng H. Practical considerations for choosing a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegeneration 2017;12:89. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0231-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glenner GG, Wong CW. Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1984;120:885–890. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(84)80190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kosik KS, Joachim CL, Selkoe DJ. Microtubule-associated protein tau (tau) is a major antigenic component of paired helical filaments in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1986:83:4044–4048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.11.4044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 2002;58:1791–1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, et al. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathologica 2006; 112:389–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mintun MA, Larossa GN, Sheline YI, et al. [11C]PIB in a nondemented population: potential antecedent marker of Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(3):446–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Buchhave P, Minthon L, Zetterberg H et al. Cerebrospinal fluid levels of β-amyloid 1-42, but not of tau, are fully changed already 5 to 10 years before the onset of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2012;69:98–106. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wippold FJ 2nd, Brown DC, Broderick DF, et al. ACR appropriateness criteria dementia and movement disorders. J Am Coll Radiol 2015;12:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL, et al. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 2001;56:1143–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pini L, Pievani M, Bocchetta M, et al. Brain atrophy in Alzheimer’s Disease and aging. Ageing Res Rev 2016;30:25–48. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2016.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Apostolova LG, Green AE, Babakchanian S, et al. Hippocampal atrophy and ventricular enlargement in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and Alzheimer Disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26:17–27. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3182163b62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rusinek H, De SS, Frid D, et al. Regional brain atrophy rate predicts future cognitive decline: 6-year longitudinal MR imaging study of normal aging. Radiology 2003;229:691–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sabri O, Sabbagh MN, Seibyl J, et al. Florbetaben PET imaging to detect amyloid beta plaques in Alzheimer’s disease: phase 3 study. Alzheimers Dement 2015;11:964–974. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2015.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Curtis C, Gamez JE, Singh U, et al. Phase 3 trial of flutemetamol labeled with radioactive fluorine 18 imaging and neuritic plaque density. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:287–294. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.4144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shepherd TM, Nayak GK. Clinical Use of Integrated Positron Emission Tomography-Magnetic Resonance Imaging for Dementia Patients. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2019;28:299–310. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0000000000000225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jagust W, Reed B, Mungas D, et al. What does fluorodeoxyglucose PET imaging add to a clinical diagnosis of dementia? Neurology 2007;69:871–77. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000269790.05105.16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Frisoni GB, Bocchetta M, Chételat G, et al. Imaging markers for Alzheimer disease: Which vs how. Neurology. 2013;81(5):487–500. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31829d86e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jang H, Park J, Woo S, et al. Prediction of fast decline in amyloid positive mild cognitive impairment patients using multimodal biomarkers. Neuroimage Clin 2019;24:101941. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imbimbo BP, Watling M. Investigational BACE inhibitors for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 2019;28:967–975. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2019.1683160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Joe E, Ringman JM. Cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease: clinical management and prevention. BMJ 2019;367:16217. doi: 10.1136/bmj.l6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kabir MT, Uddin MS, Begum MM, et al. Cholinesterase Inhibitors for Alzheimer's Disease: Multitargeting Strategy Based on Anti-Alzheimer's Drugs Repositioning. Curr Pharm Des 2019;25(33):3519–35. doi: 10.2174/1381612825666191008103141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Darreh-Shori T, Soininen H. Effects of cholinesterase inhibitors on the activities and protein levels of cholinesterases in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a review of recent clinical studies. Curr Alzheimer Res 2010;7:67–73. doi: 10.2174/156720510790274455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Szeto JY, Lewis SJ. Current Treatment Options for Alzheimer’s Disease and Parkinson’s Disease Dementia. Curr. Neuropharmacol 2016;14:326–338. doi: 10.2174/1570159X14666151208112754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Arvanitakis Z, Shah RC, Bennett DA. Diagnosis and Management of Dementia: Review. JAMA. 2019;322(16):1589–1599. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.4782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bond M, Rogers G, Peters J, et al. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of donepezil, galantamine, rivastigmine and memantine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease (review of Technology Appraisal No. 111): a systematic review and economic model. Health Technol Assess 2012;16:1–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knight R, Khondoker M, Magill N, et al. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Effectiveness of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors and Memantine in Treating the Cognitive Symptoms of Dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2018;45:131–51. doi: 10.1159/000486546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McShane R, Westby MJ, Roberts E, et al. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;3:CD003154. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003154.pub6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cui CC, Sun Y, Wang XY, et al. The effect of anti-dementia drugs on Alzheimer disease-induced cognitive impairment: A network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98:e16091. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Glinz D, Gloy VL, Monsch AU, et al. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors combined with memantine for moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. Swiss Med Wkly. 2019; doi: 10.4414/smw.2019.20093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Polanco JC, Li C, Bodea LG, et al. Amyloid-β and tau complexity - towards improved biomarkers and targeted therapies. Nat Rev Neurol 2018;14(1):22–39. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2017.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mullane K, Williams M. Preclinical Models of Alzheimer's Disease: Relevance and Translational Validity. Curr Protoc Pharmacol 2019;84(1):e57. doi: 10.1002/cpph.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang LK, Chao SP, Hu CJ. Clinical trials of new drugs for Alzheimer disease. J Biomed Sci. 2020;27:18. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0609-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Doggrell SA. Lessons that can be learnt from the failure of verubecestat in Alzheimer's disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20:2095–99. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2019.1654998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tripathi M, Tripathi M, Parida GK, et al. Biomarker-Based Prediction of Progression to Dementia: F-18 FDG-PET in Amnestic MCI. Neurol India 2019;67(5):1310–17. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.271245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gupta Y, Lama RK, Kwon GR; Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Prediction and Classification of Alzheimer's Disease Based on Combined Features From Apolipoprotein-E Genotype, Cerebrospinal Fluid, MR, and FDG-PET Imaging Biomarkers. Front Comput Neurosci 2019;13:72. doi: 10.3389/fncom.2019.00072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Frisoni GB, Boccardi M, Barkhof F, et al. Strategic roadmap for an early diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease based on biomarkers. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:661–676. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30159-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mattsson N, Lönneborg A, Boccardi M, et al. Clinical validity of cerebrospinal fluid Aβ42, tau, and phospho-tau as biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease in the context of a structured 5-phase development framework. Neurobiol Aging 2017;52:196–213. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2016.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Takousis P, Sadlon A, Schulz J, et al. Differential expression of microRNAs in Alzheimer's disease brain, blood, and cerebrospinal fluid. Alzheimers Dement. 2019;15:1468–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2019.06.4952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Herrera-Espejo S, Santos-Zorrozua B, Álvarez-González P, et al. A Systematic Review of MicroRNA Expression as Biomarker of Late-Onset Alzheimer's Disease. Mol Neurobiol 2019;56(12):8376–91. doi: 10.1007/s12035-019-01676-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang Q, Zhao Q, Yin Y. miR-133b is a potential diagnostic biomarker for Alzheimer's disease and has a neuroprotective role. Exp Ther Med. 2019;18:2711–18. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kenny A, McArdle H, Calero M, et al. Elevated Plasma microRNA-206 Levels Predict Cognitive Decline and Progression to Dementia from Mild Cognitive Impairment. Biomolecules. 2019;9:pii: E734. doi: 10.3390/biom9110734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cao F, Liu Z, Sun G. Diagnostic value of miR-193a-3p in Alzheimer's disease and miR-193a-3p attenuates amyloid-β induced neurotoxicity by targeting PTEN. Exp Gerontol. 2020;130:110814. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2019.110814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dehghani R, Rahmani F, Rezaei N. MicroRNA in Alzheimer's disease revisited: implications for major neuropathological mechanisms. Rev Neurosci 2018;29(2):161–82. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2017-0042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.D'Anca M, Fenoglio C, Serpente M, Arosio B, Cesari M, Scarpini EA, Galimberti D. Exosome Determinants of Physiological Aging and Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Aging Neurosci 2019;11:232. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Szepesi Z, Manouchehrian O, Bachiller S, Deierborg T. Bidirectional Microglia-Neuron Communication in Health and Disease. Front Cell Neurosci 2018;12:323. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2018.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mathews PM, Levy E. Exosome Production Is Key to Neuronal Endosomal Pathway Integrity in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front Neurosci 2019;13:1347. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.01347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Malone ER, Oliva M, Sabatini PJB, Stockley TL, Siu LL. Molecular profiling for precision cancer therapies. Genome Med 2020;12(1):8. doi: 10.1186/s13073-019-0703-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Penney J, Ralvenius WT, Tsai LH. Modeling Alzheimer’s disease with iPSC-derived brain cells. Mol Psychiatry 2020;25(1):148–167. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0468-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sarlus H, Heneka MT. Microglia in Alzheimer's disease. J Clin Invest 2017;127:3240–49. doi: 10.1172/JCI90606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pampuscenko K, Morkuniene R, Sneideris T, et al. Extracellular tau induces microglial phagocytosis of living neurons in cell cultures. J Neurochem 2019;e14940. doi: 10.1111/jnc.14940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]