Abstract

Background

Gait asymmetries after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) may lead to radiographic knee osteoarthritis. Slower walking speeds have been associated with biomarkers suggesting cartilage breakdown. The relationship between walking speed and gait symmetry after ACLR is unknown.

Hypothesis/Purpose

To determine the relationship between self-selected walking speeds and gait symmetry in athletes after primary, unilateral ACLR.

Study Design

Secondary analysis of a clinical trial.

Methods

Athletes 24±8 weeks after primary ACLR walked at self-selected speeds as kinematics, kinetics, and electromyography data were collected. An EMG-driven musculoskeletal model was used to calculate peak medial compartment contact force (pMCCF). Variables of interest were peak knee flexion moment (pKFM) and angle (pKFA), knee flexion and extension (KEE) excursions, peak knee adduction moment (pKAM), and pMCCF. Univariate correlations were run for walking speed and each variable in the ACLR knee, contralateral knee, and interlimb difference (ILD).

Results

Weak to moderate positive correlations were observed for walking speed and all variables of interest in the contralateral knee (Pearson’s r=.301-.505, p≤0.01). In the ACLR knee, weak positive correlations were observed for only pKFM (r=.280, p=0.02) and pKFA (r=.263, p=0.03). Weak negative correlations were found for ILDs in pKFM (r=-0.248, p=0.04), KEE (r=-.260, p=0.03), pKAM (r=-.323, p<0.01), and pMCCF (r=-.286, p=0.02).

Conclusion

Those who walk faster after ACLR have more asymmetries, which are associated with the development of early OA. This data suggests that interventions that solely increase walking speed may accentuate gait symmetry in athletes early after ACLR. Gait-specific, unilateral, neuromuscular interventions for the ACLR knee may be needed to target gait asymmetries after ACLR.

Level of Evidence

III

Keywords: walking speed, osteoarthritis, gait mechanics, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction

Introduction

Over the past decade, the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament injury and reconstruction (ACLR) procedures in young adults has increased.1–3 Gait asymmetries persist for six months to one year after ACLR and have been associated with the development of early onset radiographic osteoarthritis (OA).4–7 Athletes who developed radiographic knee OA five years after ACLR walked with underloading of the medial compartment of the tibiofemoral joint of the ACLR knee compared to those who did not develop radiographic knee OA early after reconstruction.4 Slower walking speed may be a potential predictor for future OA development.8–12 An association between slower walking and greater serum collagen type II cleavage concentration, a biomarker associated with greater cartilage breakdown in the knee, have been found in individuals six months after ACLR.6,9

In healthy individuals, faster walking speeds are associated with larger joint moments and angles in the sagittal plane.11,13 Faster walking may promote joint loading, thus could be used as a potential intervention to prevent early onset OA. Faster walking speeds are also associated with lower incidences of knee OA in mid- to older-aged adults.10 The relationship between walking speed and knee joint moments and angles during gait after ACLR is unknown.

There are no interventions that fully restore gait symmetry early after ACLR. Perturbation training, weighted vest training, and sled towing have been trialed in the past but have been unsuccessful in restoring gait symmetry.14–19 Strength, agility, plyometric, and secondary prevention training and perturbation training interventions have been shown to help mitigate asymmetry in women two years after ACLR, but not at earlier timepoints.16 Real-time visual biofeedback with verbal cues suggest that individuals may be able to modulate medial compartment tibiofemoral contact forces, thereby improving symmetry.20,21 These bio-inspired technologies are, however, costly and time-consuming to implement in a clinical setting. Understanding the association between walking speed and knee biomechanics in athletes after ACLR may inform a clinically feasible intervention based on simply altering walking speed.

The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between self-selected walking speed and gait biomechanics in athletes after ACLR. This study investigated the relationship between walking speed and knee biomechanics in the ACLR knee, in the contralateral knee, and for the interlimb differences (ILD = ACLR – contralateral knee). The first hypothesis was that faster walking speed would be related to larger knee kinematics, kinetics, and joint contact forces in both the contralateral and ACLR knees. The secondary hypothesis was that less asymmetry would be observed in gait biomechanics for those who walked faster.

Methods

This study is a secondary analysis of prospectively collected data from a clinical trial (NCT01773317) approved by the University of Delaware institutional review board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and from parents/guardians for participants who were minors.

Seventy participants (21±8 years old) (Table 1) were included in this study.22 Participants were level I and II athletes (i.e. sports involving jumping, pivoting, and cutting),23,24 who participated in their sport at least 50 hours per year prior to injury, underwent primary, unilateral ACLR, and planned on returning to their pre-injury level of sport after surgery. Athletes were eligible for study enrollment 12 weeks after ACLR. Criteria were: minimal to no effusion,25 full and symmetrical knee range of motion, ≥80% quadriceps index ([ACLR knee maximal volitional contraction (MVIC) / contralateral knee MVIC] x 100), initiation of a running progression, and ability to hop pain-free on each leg. Participants were excluded if they had a previous history of ACLR or other significant lower extremity injury or surgery on either knee, concomitant grade III knee ligament injury, or osteochondral defect ≥ 1 cm2.22 All participants from the parent clinical trial whose biomechanical testing data were able to be modeled were included in the present study.

TABLE 1: Demographic Characteristics (SD) (n=70).

| Time Since Surgery (weeks) | 23.8 (7.7) | |

| QI (%) | 91.2 (8.8) | |

| Walking speed (m/s) | 1.55 (0.1) | |

| Height (m) | 1.72 (0.1) | |

| Weight (kg) | 77.5 (14.9) | |

| BMI (kg/m²) | 25.9 (3.3) | |

| Age at Surgery (years) | 21.5 (7.9) | |

| Graft Type | Allograft | 16 |

| BPTB/Patellar Tendon | 20 | |

| Hamstring | 34 | |

| Medial Meniscus Pathology† | None | 40 |

| Partial Meniscectomy | 12 | |

| Repair | 12 | |

| Lateral Meniscus Pathology† | None | 33 |

| Partial Meniscectomy | 23 | |

| Repair | 8 | |

| Pre-injury Activity Level | 64 level I, 6 level II | |

| Sex | 33 F, 37 M | |

Abbreviations: QI, quadriceps index; BMI, body mass index; BPTB, bone patellar tendon bone

*Values are Mean (Standard deviation)

†Meniscal pathology not reported for all subjects due to missing operative reports for 6 subjects

Motion Analysis and Variables of Interest

Motion capture and EMG (1080Hz) data were collected 24±8 weeks after ACLR. Commercial software (Visual3D; CMotion, Germantown, MD) was used to calculate kinematic and kinetic variables via inverse dynamics. Thirty-nine retroreflective markers were placed on both lower extremities, and kinematic data were captured at 120 Hz using an eight-camera motion analysis system (VICON, Oxford, UK). Kinetic data were recorded using an embedded force platform (Bertec Corporation, Columbus, OH) sampling at 1080 Hz. Five over-ground gait trials were collected at self-selected walking speeds maintained at ± 5%. Electromyography (EMG) was collected via electrodes placed bilaterally on the rectus femoris, medial and lateral vasti, medial and lateral hamstrings, and the medial and lateral gastrocnemii. We collected MVICs for each muscle group and data were normalized to each muscle’s MVIC. EMG data were high-pass filtered at 30 Hz using a 2nd order Butterworth filter and low-pass filtered at 6 Hz to create a linear envelope.

Variables of interest were external peak knee flexion (pKFM) and adduction moments (pKAM), peak knee flexion angle (pKFA), and knee flexion (KFE) and extension (KEE) excursion. KFE was defined as the change in knee flexion angle from initial contact to peak knee flexion. KEE was defined as the excursion between peak knee flexion angle and peak knee extension angle during the second half of stance. Joint moments were normalized by mass and height (kg×m). pKFA and pKFM were normalized so that positive values reflect greater knee flexion angles and external knee flexion moments, respectively.

Musculoskeletal Modeling

A validated, patient-specific EMG-driven model was used to calculate the primary variable of interest, medial tibiofemoral joint contact forces (pMCCF),26,27 which has been associated with early onset OA.4,5,28 The previously validated26,27 model uses a hill-type muscle fiber in series with an elastic tendon. EMG-derived forward dynamics estimations are used to create a knee flexion moment curve, which is then fit to the knee flexion moment curve generated through inverse dynamics calculated through motion capture and ground reaction forces. We then predicted each of the five trials per knee using muscle parameters and coefficients (pennation angle, fiber velocity, tendon strain, and muscle activation) from the other four trials. The three best-fitting predicted trials were selected by maximizing R² and minimizing root mean square error values. A frontal plane moment balance algorithm was used to calculate pMCCF, the modeling-derived variable of interest.22,26,27 pMCCF was normalized to body weight to allow comparison between individuals.

Statistics

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were computed for the variables of interest (contralateral knee, ACLR knee, and ILD) and walking speed. Linear regression was computed for all variables against walking speed to assess the linear relationship between each variable and walking speed. Alpha was set at 0.05 for all statistical analyses. Analyses were computed using SPSS version 25.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Results

Contralateral Knee Mechanics

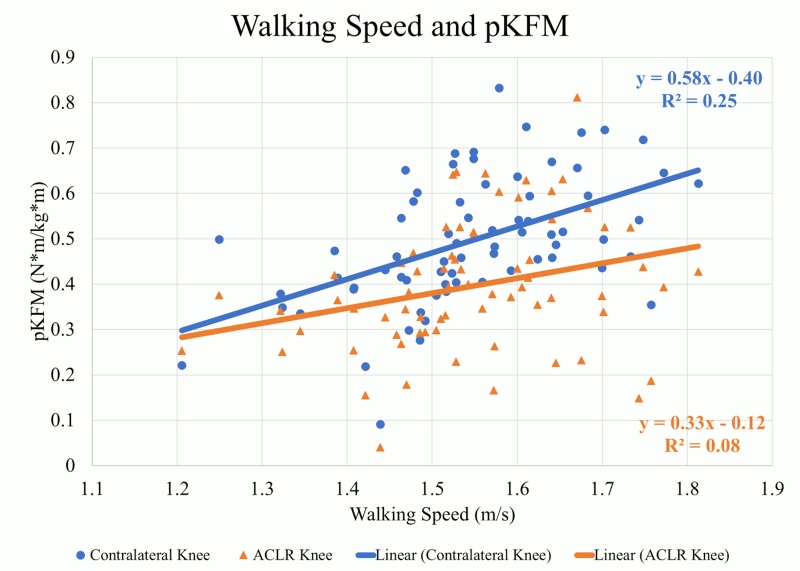

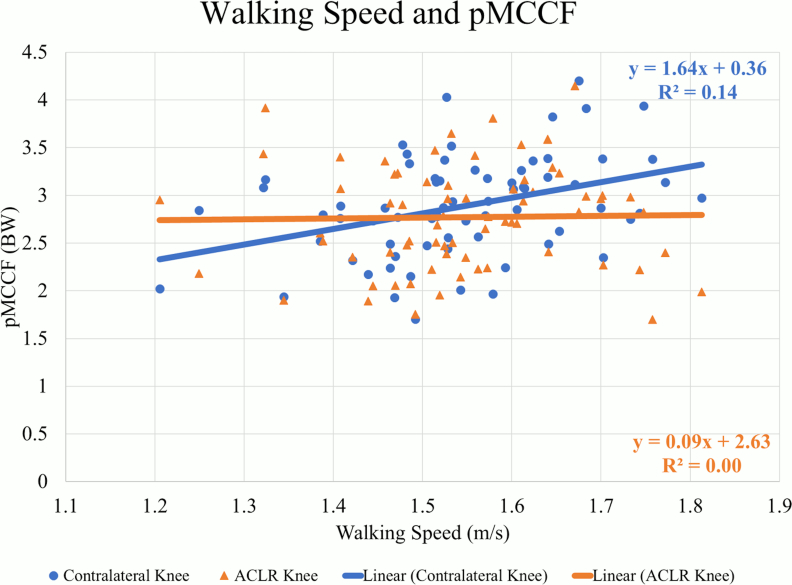

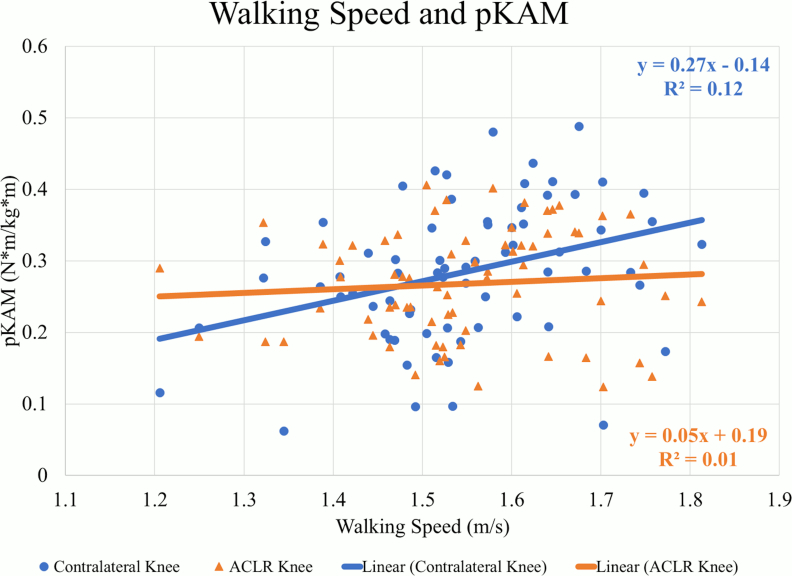

There were weak to moderate positive correlations between walking speed and mechanics indicating larger values occurred at faster speeds in the contralateral knee. At faster speeds, pKFM (Pearson’s r=.505, p<0.01) (Figure 1), pKFA (r=.449, p<0.01), KEE (r=.379, p<0.01), pMCCF (r=.377, p<0.01) (Figure 2, Table 2), pKAM (r=.346, p<0.01) (Figure 3), and KFE (r=.301, p=0.01) were greater in the contralateral knee.

FIGURE 1.

Abbreviations: PKFM, peak knee flexion moment

In the contralateral knee, there was a moderate correlation between walking speed and PKFM (p < 0.01). In the ACLR knee, there was a weak correlation between walking speed and PKFM (p = 0.02).

FIGURE 2.

Abbreviations: PMCCF, peak medial compartment contact force

In the contralateral knee, those who walked faster had higher PMCCF values than those who walked at slower speeds (p < 0.01). There was no relationship for PMCCF and walking speed in the ACLR knee (p = 0.87).

TABLE 2: Pearson’s r and R2 values for the relationship between walking speed and biomechanics in the contralateral knee.

| Biomechanical Variable | Pearson’s r | R² | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Knee Flexion Moment (pKFM) | 0.505 | 0.255 | <0.01 |

| Peak Knee Flexion Angle (pKFA) | 0.449 | 0.202 | <0.01 |

| Knee Extension Excursion (KEE) | 0.379 | 0.144 | <0.01 |

| Peak Medial Compartment Contact Force (pMCCF) | 0.377 | 0.142 | <0.01 |

| Peak Knee Adduction Moment (pKAM) | 0.346 | 0.120 | <0.01 |

| Knee Flexion Excursion (KFE) | 0.301 | 0.091 | 0.01 |

Bold p-values indicate statistically significant correlations.

FIGURE 3.

Abbreviations: PKAM, peak knee adduction moment

In the contralateral knee, those who walked faster had higher PKAM values than those who walked at slower speeds (p < 0.01). There was no relationship for PKAM and walking speed in the ACLR knee (p = 0.49).

ACLR Knee Mechanics

There were weak positive correlations observed between walking speed and pKFM (r=.280, p=0.02) (Figure 1, Table 3) and pKFA (r=.263, p=0.03) in the ACLR knee. However, there were no statistically significant correlations between walking speed and pMCCF (r=.020, p=0.87) (Figure 2), pKAM (r=.080, p=0.49) (Figure 3), KFE (r=.065, p=0.59) and KEE (r=.226, p=0.06) suggesting no strong relationship between walking speed and gait mechanics in the ACLR knee.

TABLE 3: Pearson’s r and R2 values for the relationship between walking speed and biomechanics in the ACLR knee.

| Biomechanical Variable | Pearson’s r | R² | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Knee Flexion Moment (pKFM) | 0.280 | 0.078 | 0.02 |

| Peak Knee Flexion Angle (pKFA) | 0.263 | 0.069 | 0.03 |

| Knee Extension Excursion (KEE) | 0.226 | 0.051 | 0.06 |

| Peak Medial Compartment Contact Force (pMCCF) | 0.020 | 0.000 | 0.87 |

| Peak Knee Adduction Moment (pKAM) | 0.083 | 0.007 | 0.49 |

| Knee Flexion Excursion (KFE) | 0.065 | 0.004 | 0.59 |

Bold p-values indicate statistically significant correlations.

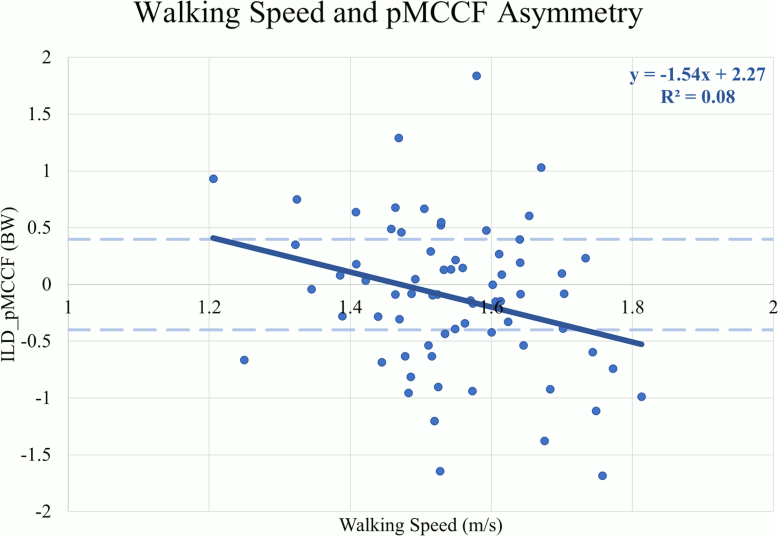

Interlimb Difference

There were weak negative correlations between walking speed and ILDs for KFE (r=-.260, p=0.03) (Table 4), pKAM (r=-.323, p<0.01), pMCCF (r=-.286, p=0.02) (Figure 4), and pKFM (r=-.248, p=0.04) indicating that more asymmetry occurred at faster speeds. There were no correlations between walking speed and ILDs for pKFA (r=-.248, p=0.07) or KEE (r=-.172, p=0.15).

TABLE 4: Pearson’s r and R2 values for the relationship between walking speed and interlimb difference (ILD) in our biomechanical variables of interest.

| Biomechanical Variable | Pearson’s r | R² | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Knee Flexion Moment (pKFM) | -0.248 | 0.062 | 0.04 |

| Peak Knee Flexion Angle (pKFA) | -0.217 | 0.047 | 0.07 |

| Knee Extension Excursion (KEE) | -0.172 | 0.030 | 0.15 |

| Peak Medial Compartment Contact Force (pMCCF) | -0.286 | 0.082 | 0.02 |

| Peak Knee Adduction Moment (pKAM) | -0.323 | 0.104 | 0.01 |

| Knee Flexion Excursion (KFE) | -0.260 | 0.068 | 0.03 |

Bold p-values indicate statistically significant correlations.

FIGURE 4.

Abbreviations: PMCCF, peak medial compartment contact force, negative ILD = underloading

Those who walked faster had relative medial tibiofemoral joint underloading of the ACLR knee and those who walked slower had relative overloading. Those who walked around 1.5 m/s walked with the most symmetry. The dashed lines at -0.4 and 0.4 BW represent the meaningful interlimb difference threshold.4

Discussion

This study explored the relationship between self-selected walking speeds and gait biomechanics in athletes after ACLR. The first hypothesis, that faster walkers would have greater knee moments, angles, and joint contact forces, was supported in the contralateral knee but only partially and weakly supported in the ACLR knee. Only pKFM and pKFA in the ACLR knee were weakly correlated to walking speed. The secondary hypothesis, that there would be less asymmetry at faster walking speeds, was not supported. Greater asymmetry was observed for pKFM and KFE at faster walking speeds, and beyond 1.5 m/s in pMCCF (trending toward underloading) and pKAM. The ACLR knee does not present with the same characteristics as the contralateral knee at faster walking speeds, suggesting that healthy responses to faster walking13 may not be observed in the ACLR knee.

Gait asymmetries persist six months after ACLR in this and other cohorts.5,16,29–31 Given that previous research suggests that faster walking leads to larger angles and moments, especially in the sagittal plane,13 the hypothesis was that there would be similar trends in both the ACLR and contralateral knees. The findings in this study, conversely indicate that those who walk faster six months after ACLR, compared to those who walk more slowly, actually have more gait asymmetry. These results indicate that walking speed is more strongly associated with contralateral knee biomechanics than ACLR knee biomechanics. The varying strength of the relationships between each limb and walking speed may explain the underlying resultant asymmetry (i.e., underloading of the involved knee) observed for those who walked faster.

For all sagittal plane variables (PKFA, PKFM, KFE, and KEE), asymmetries were present regardless of walking speed, and were exaggerated for those who walked at faster speeds. The line of best fit for the association between walking speed and the ILD in pMCCF, the primary variable of interest associated with OA development,4,5,28 and between walking speed and the ILD in pKAM both crossed zero at approximately 1.5 m/s. Individuals who walked faster tended to exhibit greater underloading in the ACLR knee relative to the contralateral knee (Figure 4), an association that was driven primarily by changes in the contralateral limb (Figure 2, Table 2). As illustrated in Figure 4, clinically meaningful pMCCF underloading, as determined by ILDs exceeding the meaningful interlimb difference threshold of 0.4 BW,4 was more prevalent at faster speeds than was pMCCF overloading. These relationships were similar for men and women, as shown in secondary exploratory analyses (Table 5). Therefore, an intervention that manipulates walking speed alone for asymmetric gait mechanics after ACLR may result in continued gait asymmetry, perhaps even increasing the asymmetry. Future research, however, must manipulate walking speed within individuals after ACLR to determine its effect on walking symmetry.

TABLE 5: Comparison of Pearson’s r for the relationship between walking speed and pMCCF in men, women, and pooled data.

| Men | Women | Pooled | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson’s r | p-value | Pearson’s r | p-value | Pearson’s r | p-value | |

| ACLR knee | 0.135 | 0.43 | -0.025 | 0.89 | 0.020 | 0.87 |

| Contralateral knee | 0.382 | 0.02 | 0.376 | 0.03 | 0.377 | <0.01 |

| Interlimb difference | -0.196 | 0.25 | -0.323 | 0.07 | -0.286 | 0.02 |

Bold p-values indicate statistically significant correlations.

The mechanism underlying the prolonged gait asymmetry following full functional recovery after ACLR is unknown. One possible explanation is neuroplastic changes after injury and reconstruction.32 Sigward et al. suggests that individuals three months after ACLR exhibit a mismatch between their loading patterns and abilities – termed “learned nonuse” – during bilateral tasks. Sit-to-stand and static standing are activities that are typically performed without attention to loading, similar to gait. Individuals in the Sigward et al. study exhibited asymmetry without cuing during the tasks, but were able to load symmetrically (measured by vertical ground reaction force impulse) once real-time visual and verbal feedbacks were provided.33 Pizzolato et al. found real-time visual biofeedback with verbal cues during gait may have short-term effects on restoring gait symmetry including variables such as medial compartment tibiofemoral contact forces.20,21 These were short-term studies and visual feedback has not been shown to improve long-term learning or transfer to other environments. With repetition and targeted intervention, however, these changes may carry over into long-term gait symmetry. Given these findings, individuals early after ACLR may benefit from external feedback focusing on neuromuscular control in the ACLR knee in order to learn to load symmetrically during gait.32

Interventions such as split-belt treadmill training may allow clinicians to unilaterally target the ACLR knee by decoupling the belts so that one limb moves faster than the other. Roper et al. found that split-belt training has the potential to increase hip adduction moment impulse of the fast limb.34 Therefore, targeting the ACLR knee using gait-specific, unilateral neuromuscular retraining early after ACLR may be promising for improving symmetry of knee moments, angles, and joint contact forces. Future research is warranted.

While the cause and effect of walking speed and underloading is unclear, both slower walking9,12 and tibiofemoral underloading5,11,16,18,28 of the ACLR knee at six months after ACLR have been associated with early OA development. In the present study, faster walkers tended to walk with tibiofemoral underloading of their ACLR knee at six months following ACLR. In contrast, slower walkers had more symmetrical medial compartment loading. These unexpected associations, however, were driven almost exclusively by the contralateral knee rather than the ACLR knee. Individuals who walked faster did not load their ACLR knee less than individuals who walked more slowly (Table 3); they only underloaded their ACLR knee relative to the contralateral limb, which experienced higher loading at faster speeds (Table 2). Optimal tibiofemoral joint loading and walking speeds early after ACLR remain unknown. Further follow-up including musculoskeletal imaging is necessary to elucidate the relationship between joint loading, walking speed, and long-term OA development.

This study was an explorative secondary analysis, so the interventions discussed are speculative in nature and should not be taken as clinical practice recommendations. The present study is limited by its cross-sectional, between-subjects design; walking speed was not manipulated. Additionally, correlations were weak to moderate. This sample may not be representative of the general ACLR population due to the stringent inclusion criteria (level I and II athletes, participated in their sport at least 50 hours/year prior to injury, primary, unilateral ACLR, and planned to return to pre-injury level of sport after ACLR). Lastly, this sample does not include long-term radiographic evidence of OA development.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that contralateral knee mechanics and loading were more strongly correlated to walking speeds (i.e., greater angles, moments, and loading with faster walking) than ACLR knee mechanics and loading. This difference may explain the larger gait asymmetries observed in faster walkers. Further research is warranted to study targeted interventions to improve gait symmetry for individuals after ACLR. These results suggest that those who walk faster demonstrate greater interlimb asymmetry, rather than less asymmetry. Therefore, manipulating walking speed alone as an intervention for targeting aberrant gait mechanics may accentuate, rather than mitigate, walking asymmetries among individuals after ACLR. Further research is necessary to understand the long-term effect of different walking speeds on gait biomechanics within the same individual. Gait-specific, unilateral, neuromuscular training for the ACLR knee may be necessary to improve symmetry in postoperative rehabilitation.

The Institutional Review Board of the University of Delaware approved this study, which was registered on IRBNet (ID 225014-15). This is a secondary analysis of a clinical trial which was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01773317). This study was supported by the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (R01-AR048212) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R37-HD037985, T32-HD007490, F30-HD096830). This study was funded in part by The Foundation for Physical Therapy Research Promotion of Doctoral Studies (PODS) Level I and II Scholarships (JJC), University of Delaware Doctoral Fellowship Award (JJC), Dissertation Fellowship Award (JJC), and Biomechanics and Movement Science (BIOMS) tuition scholarship (NI). JJC’s postdoctoral training is funded by an Advanced Geriatrics Fellowship from the Eastern Colorado Veterans Affairs Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center. The authors certify that they have no financial disclosures or direct financial interest in the subject matter. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Trends in incidence of ACL reconstruction and concomitant procedures among commercially insured individuals in the United States, 2002-2014. Herzog Mackenzie M, Marshall Stephen W, Lund Jennifer L, Pate Virginia, Mack Christina D, Spang Jeffrey T. 2018Sports Health. 10(6):523–531. doi: 10.1177/1941738118803616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Increasing rates of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in young Australians, 2000-2015. Zbrojkiewicz David, Vertullo Christopher, Grayson Jane E. May 7;2018 Medical Journal of Australia. 208(8):354–358. doi: 10.5694/mja17.00974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marked increase in the incidence of anterior cruciate ligament reconstructions in young females in New Zealand. Sutherland Kirsty, Clatworthy Mark, Fulcher Mark, Chang Kevin, Young Simon W. Sep;2019 ANZ journal of surgery. 89(9):1151–1155. doi: 10.1111/ans.15404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gait mechanics in those with/without medial compartment knee osteoarthritis 5 years after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Khandha Ashutosh, Manal Kurt, Wellsandt Elizabeth, Capin Jacob, Snyder-Mackler Lynn, Buchanan Thomas S. 2017Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 35(3):625–633. doi: 10.1002/jor.23261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decreased knee joint loading associated with early knee osteoarthritis after anterior cruciate ligament injury. Wellsandt Elizabeth, Gardinier Emily S, Manal Kurt, Axe Michael J, Buchanan Thomas S, Snyder-Mackler Lynn. Jan;2016 The American journal of sports medicine. 44(1):143–51. doi: 10.1177/0363546515608475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical markers of cartilage metabolism are associated with walking biomechanics 6-months following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Pietrosimone Brian, Loeser Richard F., Blackburn J. Troy, Padua Darin A., Harkey Matthew S., Stanley Laura E., Luc-Harkey Brittney A., Ulici Veronica, Marshall Stephen W., Jordan Joanne M., Spang Jeffery T. 2017Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 35(10):2288–2297. doi: 10.1002/jor.23534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greater magnitude tibiofemoral contact forces are associated with reduced prevalence of osteochondral pathologies 2–3 years following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Saxby David John, Bryant Adam L., Van Ginckel Ans, Wang Yuanyuan, Wang Xinyang, Modenese Luca, Gerus Pauline, Konrath Jason M., Fortin Karine, Wrigley Tim, Bennell Kim L., Cicuttini Flavia M., Vertullo Christopher, Feller Julian A., Whitehead Tim, Gallie Price, Lloyd David G. 2019Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 27(3):707–715. doi: 10.1007/s00167-018-5006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gait mechanics and T1ρ MRI of tibiofemoral cartilage 6 months after ACL reconstruction. Pfeiffer Steven J, Spang Jeffrey, Nissman Daniel, Lalush David, Wallace Kyle, Harkey Matthew S, Pietrosimone Laura S, Schmitz Randy, Schwartz Todd, Blackburn Troy, Pietrosimone Brian. 2019Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 51(4):630–639. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walking speed as a potential indicator of cartilage breakdown following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Pietrosimone Brian, Troy Blackburn J., Harkey Matthew S., Luc Brittney A., Hackney Anthony C., Padua Darin A., Driban Jeffrey B., Spang Jeffrey T., Jordan Joanne M. 2016Arthritis Care and Research. 68(6):793–800. doi: 10.1002/acr.22773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Association of slower walking speed with incident knee osteoarthritis- related outcomes. Purser Jama L., Golightly Yvonne M., Feng Qiushi, Helmick Charles G., Renner Jordan B., Jordan Joanne M. 2012Arthritis Care and Research. 64(7):1028–1035. doi: 10.1002/acr.21655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Differences in gait parameters between healthy subjects and persons with moderate and severe knee osteoarthritis: A result of altered walking speed? Zeni Joseph A., Higginson Jill S. 2009Clinical Biomechanics. 24(4):372–278. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slower walking speed is related to early femoral trochlear cartilage degradation after ACL reconstruction. Capin Jacob J., Williams Jack R., Neal Kelsey, Khandha Ashutosh, Durkee Laura, Ito Naoaki, Stefanik Joshua J., Snyder‐Mackler Lynn, Buchanan Thomas S. 2020Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 38(3):645–652. doi: 10.1002/jor.24503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predicting peak kinematic and kinetic parameters from gait speed. Lelas Jennifer L., Merriman Gregory J., Riley Patrick O., Kerrigan D. Casey. 2003Gait and Posture. 17(2):106–112. doi: 10.1016/S0966-6362(02)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lower limb moments differ when towing a weighted sled with different attachment points. Lawrence Michael, Hartigan Erin, Tu Chunhao. Jun;2013 Sports biomechanics. 12(2):186–94. doi: 10.1080/14763141.2012.726639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biomechanical profiles when towing a sled and wearing a weighted vest once cleared for sports post–ACL reconstruction. Hartigan Erin, Lawrence Michael, Murray Thomas, Shaw Bernadette, Collins Erin, Powers Kaitlin, Townsend James. 2016Sports Health. 8(5):456–464. doi: 10.1177/1941738116659855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gait mechanics in women of the ACL-SPORTS randomized control trial: Interlimb symmetry improves over time regardless of treatment group. Capin Jacob J., Zarzycki Ryan, Ito Naoaki, Khandha Ashutosh, Dix Celeste, Manal Kurt, Buchanan Thomas S., Snyder-Mackler Lynn. 2019Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 37(8):1743–1753. doi: 10.1002/jor.24314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Functional and patient-reported outcomes improve over the course of rehabilitation: A secondary analysis of the ACL-SPORTS trial. Arundale Amelia J.H., Capin Jacob J., Zarzycki Ryan, Smith Angela, Snyder-Mackler Lynn. Sep 1;2018 Sports Health. 10(5):441–452. doi: 10.1177/1941738118779023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Report of the primary outcomes for gait mechanics in men of the ACL-SPORTS trial: Secondary prevention with and without perturbation training does not restore gait symmetry in men 1 or 2 years after ACL reconstruction. Capin Jacob John, Zarzycki Ryan, Arundale Amelia, Cummer Kathleen, Snyder-Mackler Lynn. 2017Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 475(10):2513–2522. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5279-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Report of the clinical and functional primary outcomes in men of the ACL-SPORTS trial: Similar outcomes in men receiving secondary prevention with and without perturbation training 1 and 2 years after ACL reconstruction. Arundale Amelia J.H., Cummer Kathleen, Capin Jacob J., Zarzycki Ryan, Snyder-Mackler Lynn. 2017Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 475(10):2523–2534. doi: 10.1007/s11999-017-5280-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biofeedback for gait retraining based on real-time estimation of tibiofemoral joint contact forces. Pizzolato Claudio, Reggiani Monica, Saxby David J., Ceseracciu Elena, Modenese Luca, Lloyd David G. Sep 1;2017 IEEE Transactions on Neural Systems and Rehabilitation Engineering. 25(9):1612–1621. doi: 10.1109/TNSRE.2017.2683488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bioinspired technologies to connect musculoskeletal mechanobiology to the person for training and rehabilitation. Pizzolato Claudio, Lloyd David G., Barrett Rod S., Cook Jill L., Zheng Ming H., Besier Thor F., Saxby David J. Oct 18;2017 Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience. 11 doi: 10.3389/fncom.2017.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anterior cruciate ligament-specialized post-operative return-to-sports (ACL-SPORTS) training: A randomized control trial. White Kathleen, Di Stasi Stephanie L., Smith Angela H., Snyder-Mackler Lynn. 2013BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 23(14):108. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of knee ligament injuries with the IKDC form. Hefti F, Müller W, Jakob R P, Stäubli H U. 1993Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA. 1(3-4):226–34. doi: 10.1007/BF01560215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A rationale for assessing sports activity levels and limitations in knee disorders. Noyes F R, Barber S D, Mooar L A. Sep;1989 Clinical orthopaedics and related research. (246):238–49. [PubMed]

- Interrater reliability of a clinical scale to assess knee joint effusion. Sturgill Lynne Patterson, Snyder-Mackler Lynn, Manal Tara Jo, Axe Michael J. 2009Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 39(12):845–849. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2009.3143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An electromyogram-driven musculoskeletal model of the knee to predict in vivo joint contact forces during normal and novel gait patterns. Manal Kurt, Buchanan Thomas S. 2013Journal of Biomechanical Engineering. 135(2):0210141–0210147. doi: 10.1115/1.4023457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuromusculoskeletal modeling: Estimation of muscle forces and joint moments and movements from measurements of neural command. Buchanan Thomas S., Lloyd David G., Manal Kurt, Besier Thor F. 2004Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 20(4):367–395. doi: 10.1123/jab.20.4.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of knee joint loading after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Wellsandt Elizabeth, Khandha Ashutosh, Manal Kurt, Axe Michael J., Buchanan Thomas S., Snyder-Mackler Lynn. 2017Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 35(3):651–656. doi: 10.1002/jor.23408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gait mechanics and second ACL rupture: Implications for delaying return-to-sport. Capin Jacob J., Khandha Ashutosh, Zarzycki Ryan, Manal Kurt, Buchanan Thomas S., Snyder-Mackler Lynn. 2017Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 35(9):1894–1901. doi: 10.1002/jor.23476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walking gait asymmetries 6 months following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction predict 12-month patient-reported outcomes. Pietrosimone Brian, Blackburn J. Troy, Padua Darin A., Pfeiffer Steven J., Davis Hope C., Luc-Harkey Brittney A., Harkey Matthew S., Stanley Pietrosimone Laura, Frank Barnett S., Creighton Robert Alexander, Kamath Ganesh M., Spang Jeffery T. Nov 1;2018 Journal of Orthopaedic Research. 36(11):2932–2940. doi: 10.1002/jor.24056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilateral gait 6 and 12 months post-anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction compared with controls. Davis-Wilson Hope C., Pfeiffer Steven J., Johnston Christopher D., Seeley Matthew K., Harkey Matthew S., Blackburn J. Troy, Fockler Ryan P., Spang Jeffrey T., Pietrosimone Brian. Apr 1;2020 Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 52(4):785–794. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000002208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuroplasticity following anterior cruciate ligament injury: A framework for visual-motor training approaches in rehabilitation. Grooms Dustin, Appelbaum Gregory, Onate James. May 1;2015 Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. 45(5):381–393. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2015.5549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loading behaviors do not match loading abilities postanterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Chan Ming-Sheng, Sigward Susan M. Aug;2019 Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 51(8):1626–1634. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Split-belt treadmill walking alters lower extremity frontal plane mechanics. Roper Jaimie A., Roemmich Ryan T., Tillman Mark D., Terza Matthew J., Hass Chris J. Aug 1;2017 Journal of Applied Biomechanics. 33(4):256–260. doi: 10.1123/jab.2016-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]