Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted medical education worldwide, leading medical students to organize response initiatives. This paper summarizes the Washington University Medical Student COVID-19 Response (WUMS-CR) and shares lessons to guide future initiatives. We used a three-principle framework of community needs assessment, faculty mentorship, and partnership with pre-existing organizations to address needs in St. Louis, including contact tracing and childcare. In total, over 12,000 h were volunteered across 15+ projects. Overall, student response initiatives should use appropriate frameworks to guide projects and should capitalize on volunteer participation, speed and flexibility, and the diversity of student interests and skills for maximal impact.

Keywords: COVID-19, Medical Student Response, Volunteering, Community Service

Background

As of mid-January 2021, the COVID-19 pandemic has claimed nearly 375,000 lives in the USA and 2 million worldwide [1, 2]. Early on, containment measures, such as social distancing and stay-at-home orders, reduced viral transmission but disrupted everyday life [3]. Medical students had their training interrupted when preclinical lectures were transitioned online and clinical rotations were suspended [4]. These students, faced with more time and a desire to help, began organizing responses to help with the pandemic across the nation [5, 6].

The Washington University Medical Student COVID-19 Response (WUMS-CR) organized many of these efforts in the Washington University and St. Louis communities. Our response sought to meet the needs of our community with the unique and diverse skill sets of medical students. While others have described similar medical student initiatives during the COVID-19 pandemic [5, 7] or focused on single projects such as contact tracing [8], our goal is to use the WUMS-CR as a case study to share our guiding framework and the key factors underlying our response’s success. We hope to inform future medical student responses during crises and underscore the value of student responses in medical education [9].

Activity

Guiding Framework

Three principles guided our student response to improve the impact of our community engagement. These were developed with faculty, based on best practices [10–12]. First, every project was motivated by a request from our community [13, 14]. This helped us to avoid projects based solely on interest, which would detract from those our community needed most. Second, every project incorporated faculty guidance. Faculty facilitated effective project implementation and helped us to partner with institutional responses. Third, every project partnered with pre-existing community organizations when possible [13, 14]. This approach allowed students to make an impact more quickly, facilitated adherence to existing best practices, supported continuity beyond student involvement, and acknowledged the lived expertise of community members already embedded in the work. This framework helped us to prioritize and implement projects to create a sustainable impact in our community.

Establishment

On March 13, 2020, we surveyed medical students to gauge their interest in forming a student response to help with COVID-19. Within 24 h, over 100 students had expressed strong interest, so we formed the WUMS-CR.

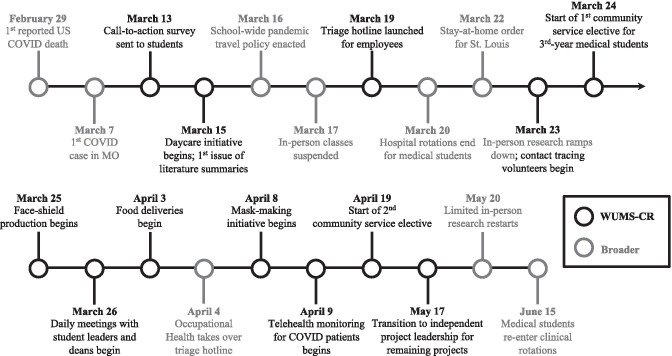

Initially, requests were funneled through the medical school deans. Based on these requests, the first volunteer projects launched were as follows: (1) childcare for essential healthcare workers, (2) literature summaries of emerging research sent to hospital staff daily, and (3) a student-run triage hotline for occupational health questions (Fig. 1). After these projects were launched, other needs arose, including face-shield and mask production. We made a university website to increase awareness and enable community members to contact us directly [15].

Fig. 1.

Timeline of events for the Washington University Medical Student COVID-19 Response (WUMS-CR) in the context of broader events

Our faculty oversight initially consisted of daily meetings with medical school deans. This guidance allowed us to safely and effectively recruit volunteers and launch projects. Through this relationship, we helped to develop and coordinate a community service elective for medical students whose clinical rotations were suspended. Students were offered credit if they volunteered with the WUMS-CR for 20 h per week. Through March and April, as we implemented other projects based on need, we recruited other faculty mentors with expertise in those areas.

Throughout the effort, we partnered with pre-existing community organizations whenever possible. As the first wave of COVID-19 cases surged, we supported the St. Louis City and County Departments of Public Health (DPH) with contact tracing and case investigations as they hired and trained more workers. To facilitate a food delivery project, we partnered with an existing non-profit that was already focused on grocery deliveries to high-risk community members. To maximize mask-making and PPE kit efforts, we supported PrepareSTL, a local campaign that was already working to prepare the St. Louis community for COVID-19 [16].

By mid-May, the need for certain projects declined as the community adjusted to a new normal. Many projects wound down as students began studying for board examinations and research ramped back up. Others, like the food delivery project, partnered with outside organizations and continued to expand beyond medical students. In response to these changes, the WUMS-CR transitioned from central leadership to project-by-project oversight.

Data Collection and Analysis

We collected volunteer hours and impact metrics between March 15 and June 23, 2020. Students self-reported their hours for each project using a weekly Qualtrics survey (Appendix 1). Other quantitative measures, such as the number of face-shields produced and families helped with childcare, were tracked by student coordinators and community partners. Metrics were compiled by activity using Microsoft Excel.

Results

The WUMS-CR helped the Washington University and St. Louis communities through several projects (Table 1). More than 12,000 volunteer hours were logged by students at Washington University School of Medicine during the first 3 months of operation. Together, WUMS-CR volunteer efforts amounted to the same time commitment as approximately 24 staff working full-time (40 h/week) for 3 months. The three most prolific initiatives were contact tracing and case investigation (3636 h), childcare for healthcare workers (2107 h), and face-shield production (1112 h). Seventy-six students enrolled in the community service elective and accounted for 8033 volunteer hours (68% of total).

Table 1.

Project summary for the Washington University Medical Student COVID-19 Response (WUMS-CR)

| Project | Hours | Length | Time to Implement | Deliverables |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact tracing and case investigation | 3,636 | Ongoing | 12 days | 2400 cases tracked* |

| Childcare for healthcare workers | 2,107 | 10 weeks | 4 days | 46 children cared for |

| Face-shield production** | 1,112 | 4 weeks | 3 days | 1665 face shields produced |

| Think tank | 675 | 8 weeks | 10 days | 14 proposals written |

| Face mask production | 618 | 3 weeks | 5 days | 1435 face masks produced |

| Coordination | 465 | 9 weeks | 1 day | 19 projects developed |

| Literature review | 459 | 10 weeks | 2 days | 452 articles summarized |

| Food delivery | 430 | Ongoing | 16 days | 10,440 meals delivered |

| Infection prevention team | 383 | 8 weeks | 3 days | Policy changes at VA hospital |

| Email triage for occupational health | 339 | 3 weeks | 5 days | 1800 emails to triage employees |

| PPE kit assembly | 333 | Ongoing | 15 days | 30,000 kits created* |

| Telehealth and testing callback | 244 | 4 weeks | 5 days | 227 patients called |

| Non-English resource production | 203 | 4 weeks | 4 days | 54 educational resources |

| Virtual help desk for families | 135 | 6 weeks | 6 days | Troubleshooting program at hospital |

| N95 reuse safety testing | 114 | 8 weeks | 2 days | Manuscript on quality assurance [17] |

| Other*** | 799 | Various | - | - |

| Total | 12,052 | |||

*Best estimate based on available data

**Includes manually assembled and 3D-printed face-shields, which were separate projects

***Includes smaller projects such as blood drives, creation of infographics and educational videos, and mental health outreach through the Department of Psychiatry

Discussion

Using the three principles of community needs assessment, faculty mentorship, and partnership with pre-existing organizations, the WUMS-CR was efficient, impactful, and educational [17]. The response helped the Washington University and St. Louis communities to help overcome the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic [18, 19]. Additionally, the response allowed students to develop skills through volunteering, while traditional educational opportunities were suspended. Through leading the WUMS-CR, we learned that its success depended on three key factors—volunteer participation, speed and flexibility, and the diversity of student interests and skills—which should generalize to future student-led emergent responses.

Volunteer Participation

The impact of the WUMS-CR relied upon strong volunteer participation. While the initial survey showed that medical students were highly motivated to help, at least two factors helped channel this motivation into strong participation. First, with in-person activities suspended, many students had extra time, which many chose to spend volunteering. Second, due to strong institutional support, we were able to develop a community service elective, which protected time to devote to the WUMS-CR and established a weekly hour target. Overall, this highlights how institutional support can amplify the impact of student-led responses.

Speed and Flexibility

A significant strength of the WUMS-CR was students’ speed and flexibility in quickly launching, adapting to needs, and completing projects, especially compared with the more fixed schedules of institutional employees. For example, a triage email project was implemented in 5 days and provided support for 3 weeks, while the larger-scale institutional response was put into place. In parallel, a different project prototyped and manually assembled over 1200 face-shields in just 3 days. Overall, students displayed remarkable flexibility in filling new roles and adapting projects as soon as new needs arose.

Diversity of Student Interests and Skills

The WUMS-CR consisted of student volunteers with a variety of interests, skills, and backgrounds. To create maximal impact, we leveraged these interests and skills within projects centered around community needs rather than starting projects based on the interests and skills. For example, when the DPH needed to transition from paper-based records for contact tracing to a more efficient electronic system, students with expertise in coding and data collection used their skills to help implement a REDCap® database.

Our work had limitations. First, student efforts often suffer from less continuity and sustainability compared with institutional initiatives [20]. This is because, while flexible and responsive, students have rapidly changing responsibilities and availability throughout medical school. To address this issue, we partnered with the institution or community whenever possible. In many cases, we “handed off” our response to an institutional group once it was implemented. For example, while the triage hotline effectively managed concerns in the short term, we handed this project off to the institution-established call center because it could function more reliably in the long term. Second, the full impact of the response on community partners was difficult to formally survey during a pandemic. Instead, we relied upon informal feedback to ensure we were addressing true needs at all times. Third, our self-reporting of hours was subject to bias, so we implemented weekly oversight from project leaders.

In conclusion, the WUMS-CR was formed to help the Washington University and St. Louis communities to respond to the challenges of COVID-19. We employed the three-principle framework of community needs assessment, faculty mentorship, and partnership with pre-existing organizations. Over 3 months, more than 12,000 volunteer hours were logged across more than a dozen projects, demonstrating the efficiency and impact of medical student projects. Through leading the WUMS-CR, we learned that its success depended on three factors: strong student participation, speed and flexibility, and the diverse array of student interests and skills. The WUMS-CR shows that medical student initiatives can be impactful and serve as a component of medical education. Therefore, such student-led initiatives should be encouraged whenever opportunities arise.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to all of the student leaders and volunteers who made this initiative possible. We thank Dr. LJ Punch for developing the guiding framework and Dr. Lisa Moscoso for helping to initiate the response. We appreciate Virgil Tipton for assistance with branding and communications.

Author Contribution

Authors’ roles: Conception of work: CCS, KD, CG, BP, EMA, and SJL. Contribution to work: CCS, KD, CG, BP, SA, JVG, NM, KP, HS, AC, EMA, and SJL. Data collection: CCS, KD, CG, and BP. Data analysis: CG. Data interpretation: CCS, KD, CG, BP, and SJL. Drafting manuscript: CCS, KD, CG, BP, EMA, and SJL. Revising manuscript content: CCS, KD, CG, BP, SA, JVG, NM, KP, HS, AC, EMA, and SJL. Approving final version of manuscript: CCS, KD, CG, BP, SA, JVG, NM, KP, HS, AC, EMA, and SJL. All authors take responsibility for the integrity of the work.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

The described work was in accordance with the ethical standards of the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments but was never submitted to a full ethics committee given the nature of the volunteering effort.

Informed Consent

No identifying information is present in this manuscript, but volunteers consented to self-report their hours.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Christopher J. Chermside-Scabbo, Katherine Douglas, Cyrus Ghaznavi, and Bruin Pollard contributed equally to this work

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40670-021-01225-x.

References

- 1.CDC COVID Data Tracker [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases

- 2.Coronavirus (COVID-19) Deaths—statistics and research [Internet]. Our World in Data. [cited 2021 Jan 10]. Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-deaths

- 3.Matrajt L, Leung T. Evaluating the effectiveness of social distancing interventions to delay or flatten the epidemic curve of coronavirus disease - Volume 26, Number 8—August 2020 - Emerging Infect Dis J - CDC. [cited 2020 Aug 7]; Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/eid/article/26/8/20-1093_article [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Kim CS, Lynch JB, Cohen S, Neme S, Staiger TO, Evans L, et al. One academic health system’s early (and ongoing) experience responding to COVID-19: recommendations from the initial epicenter of the pandemic in the United States. Acad Med. 2020;95:1146–1148. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Soled D, Goel S, Barry D, Erfani P, Joseph N, Kochis M, et al. Medical student mobilization during a crisis: lessons from a COVID-19 medical student response team. Acad Med. 2020;95:1384–1387. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Medical Student COVID-19 Action Network (MSCAN). The MSCAN Map [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 7]. Available from: https://mscan.publichealthcoalition.org/

- 7.Kratochvil TJ, Khazanchi R, Sass RM, Caverzagie KJ. Aligning student-led initiatives and Incident Command System resources in a pandemic. Med Educ. 2020;54:1183–1184. doi: 10.1111/medu.14265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koetter P, Pelton M, Gonzalo J, Du P, Exten C, Bogale K, et al. Implementation and process of a COVID-19 contact tracing initiative: leveraging health professional students to extend the workforce during a pandemic. Am J Infect Control Elsevier. 2020;48:1451–1456. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Funston G. The promotion of academic medicine through student-led initiatives. Int J Med Educ. 2015;6:155–157. doi: 10.5116/ijme.563a.5e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michener JL, Yaggy S, Lyn M, Warburton S, Champagne M, Black M, et al. Improving the health of the community: Duke’s experience with community engagement. Acad Med. 2008;83:408–413. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181668450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook DC, Nelson E-L, Ast C, Lillis T. A systematic strategic planning process focused on improved community engagement by an academic health center: the University of Kansas Medical Center’s Story. Acad Med. 2013;88:614–619. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828a3ba4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chamberlain LJ. Population health education integrating collaborative population health projects into a medical student curriculum at. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Core principles of community engagement [Internet]. Plone site. [cited 2021 Jan 10]. Available from: https://aese.psu.edu/research/centers/cecd/engagement-toolbox/engagement/core-principles-of-community-engagement

- 14.Chapter 2. Principles of community engagement | Principles of Community Engagement | ATSDR [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2021 Jan 10]. Available from: https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pce_principles_intro.html

- 15.Home | Student COVID-19 Response | Washington University in St. Louis [Internet]. [cited 2020 Aug 8]. Available from: https://studentcovid19response.wustl.edu/

- 16.PrepareSTL—preparing the St Louis Region for COVID19 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 14]. Available from: https://www.preparestl.com/

- 17.Maranhao B, Scott AW, Scott AR, Maeng J, Song Z, Baddigam R, et al. Probability of fit failure with reuse of N95 mask respirators. Br J Anaesth. 2020;125:e322–e324. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Medical Campus students mobilize to help health-care workers, community [Internet]. Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. 2020 [cited 2020 Dec 14]. Available from: https://medicine.wustl.edu/news/medical-campus-students-mobilize-to-help-health-care-workers-community/

- 19.St. Louis Med Students launch COVID-19 volunteer effort [Internet]. St. Louis Public Radio. 2020 [cited 2021 Jan 11]. Available from: https://news.stlpublicradio.org/health-science-environment/2020-03-30/st-louis-med-students-launch-covid-19-volunteer-effort

- 20.Williams E, Armstrong M. Increasing trust and communication in medical education through a student-led social justice initiative. Acad Med. 2019;94:752–753. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.