Abstract

Background

Somalia, a country with a long history of instability, has a fragile healthcare system that is consistently understaffed. A large number of healthcare workers (HCWs) have become infected during the coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Objective

This report presents the preliminary findings of COVID-19 infection in Somali HCWs, the first of such information from Somalia.

Methods

This preliminary retrospective study analysed available data on infection rates among Somali HCWs.

Results

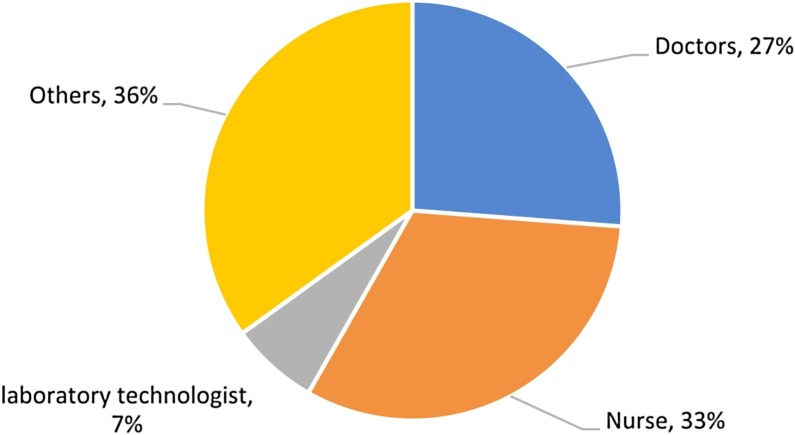

As of 30 September 2020, 3700 cases of COVID-19, including 98 deaths, had been reported in Somalia; 191 (5%) of these cases were HCWs. During the first 180 days of the outbreak, 311 HCWs were tested for COVID-19 and 191 tested positive (positivity rate: 61%). During the epidemic’s peak, HCWs represented at least 5% of cases. Of the 191 infected cases, 52 (27%) were doctors, 63 (33%) were nurses, seven (4%) were laboratory technicians, and 36% were other staff.

Conclusion

More information must be sought to put measures in place to protect the health and safety of HCWs in Somalia’s already understaffed and fragile healthcare system.

Keywords: Somalia, Healthcare workers, COVID-19, Public health, Pandemic

Introduction

Somalia has a long history of war, conflicts, violence and political instability; this has resulted in a fragile, fragmented and weak healthcare system. Aid workers have often been targeted for carrying out life-saving humanitarian work. The country’s capacity to prevent, detect and respond to emerging and expanding health threats such as coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) has been substantially lowered. The Global Health Security Index in 2019 was 16.6 out of 100, indicating that the country was unprepared to manage such epidemics (Homepage - GHS Index, n.d.). At the onset of the pandemic, Somalia had not one laboratory with the capacity to diagnose coronavirus (Ahmed Mohammed et al., 2020a, Ahmed Mohammed et al., 2020b) and the country’s health workforce was severely limited.

In the absence of a strong system for surveillance and response, the government focused its efforts on testing only suspected cases (Ahmed Mohammed et al., 2020a, Ahmed Mohammed et al., 2020b). As such, the actual number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in Somalia has likely been underestimated. Limited information is available on the burden of COVID-19 infection among healthcare workers (HCWs) in fragile and weak healthcare systems (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2020).

This study presents the preliminary findings of COVID-19 infection in Somali HCWs, the first of such information from Somalia. As of 30 September 2020, 3700 cases of COVID-19, including 98 associated deaths, have been reported in Somalia. Of these cases, 191 (5%) were HCWs, two of whom died. Owing to probable underreporting, weak surveillance reporting systems in hospital settings, stigma associated with testing/self-reporting as infected and because most cases present with mild or asymptomatic infection, the reported number of HCWs who contracted COVID-19 may be an underestimation.

Geographic distribution: all states reported infection in HCWs

During the first 180 days of the outbreak, 311 HCWs were tested for COVID-19; 191 tested positive, with a positivity rate of 61%. While all six states in the country reported infection in HCWs, there were states where very high positivity rates were reported (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

COVID-19 infection in HCWs in Somalia, 16 March–30 September 2020.

| State/region | HCWs tested for COVID-19, no. | Tested positive, no. (%) | Deaths, no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Banaadir region | 72 | 48 (67) | 1 |

| Jubaland state | 27 | 27 (100) | 0 |

| South West state | 95 | 45 (47) | 1 |

| Galmudug state | 61 | 26 (43) | 0 |

| Somaliland | 31 | 22 (71) | 0 |

| Hirshabelle state | 10 | 10 (100) | 0 |

| Puntland state | 15 | 13 (87) | 0 |

| Total | 311 | 191 (61) | 2 |

Weekly progression: infection in HCWs mirrored the country-wide exponential increase

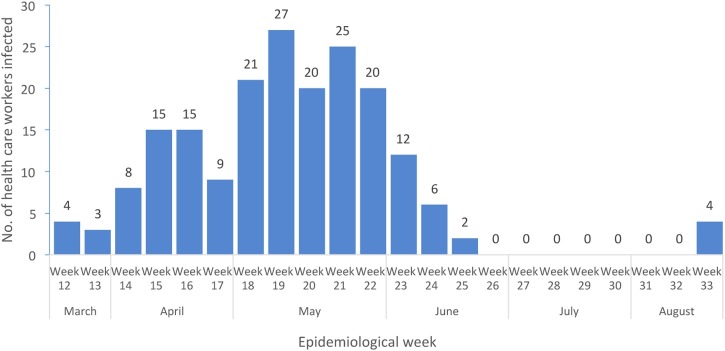

Data on COVID-19 in HCWs showed that between epidemiological weeks 18 and 22 in May 2020, when the number of cases across the country was also increasing and the outbreak spread rapidly, more HCWs (113/191; 59%) were infected during this peak period. However, the trend varied throughout this outbreak (Figure 1 ). Despite limited available data, it seems that during the peak of the outbreak, frontline HCWs represented >5% of all cases of COVID-19. In some other countries, such as in Italy, at least 20% of all COVID-19 cases during the epidemic’s peak were in frontline HCWs (The Lancet, 2020).

Figure 1.

COVID-19 infections in HCWs in Somalia, by epidemiological week, 16 March–30 September 2020.

Infection distribution among HCWs

The current data also suggest that of the 191 HCWs who contracted COVID-19 between 16 March and 30 September 2020, 52 (27%) were doctors treating COVID-19 cases in hospitals and 63 (33%) were nurses directly and indirectly involved in managing infected patients. Seven (4%) of the laboratory technicians engaged in sample collection/handling were infected. Other staff working in the healthcare setting (e.g. cleaners, security guards, ambulance drivers, etc.) comprised 36% (68/191) (Figure 2 ). This occupational pattern indicates a higher infection rate in HCWs either working in emergency rooms or providing critical care support for patients in high containment (intensive care) and indoor settings (e.g. laboratories, sample collection centres and isolation centres). The current data indicate that the hospital ancillary staff (cleaners, security guards, housekeepers, ambulance drivers, etc.) had the highest rate of infection (36%) amongst all HCWs; nurses had the second highest (33%), while doctors had the lowest rate of infection (27%). The data also show that men were at higher risk of infection than women: 150/191 (79%) men contracted COVID-19 compared with 41/191 (21%) women. Such findings were similar to those seen elsewhere and this needs to be further explored (Sim, 2020, Bandyopadhyay et al., 2020).

Figure 2.

Occupation of healthcare workers with COVID-19.

Protecting HCWs: a priority in view of shortages

Protecting frontline HCWs during any public health emergency should remain a high priority, especially in fragile settings where the health workforce is significantly smaller than it should be to meet the Sustainable Development Goals. The sub-Saharan region has 0.2 doctors for every 1000 people, and this is well below the global average of 1.6 (Wadvalla, 2020)1 .

Based on experience with other respiratory viruses, consistent use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is important in reducing transmission. However, anecdotal data suggest that shortages of masks, respirators, face shields and gowns, caused by the surge in demand and supply chain disruptions at the beginning of the outbreak, might have led to efforts to conserve PPE through extended use or reuse by HCWs.

The current data showing the relatively high risk of infection amongst the hospital ancillary staff compared with other groups of HCWs, such as doctors and nurses, merits further investigation. A possible explanation of this difference could be that the knowledge, risk perception and adherence of frontline hospital ancillary staff, compared with doctors and nurses, to strict infection control measures while handling patients with suspected COVID-19 has been fairly poor in the country. A lack of proper training and knowledge of mitigation of risk of human-to-human transmission caused by a novel pathogen such as the SARS-COV-2 virus may explain why this category of staff has been more susceptible to infection. Most ancillary staff working in hospital settings in Somalia belong to an informal employment sector and do not receive sufficient attention compared with employees in the formal sector (e.g. doctors, nurses and laboratory technologists). The lack of investment, training or capacity building for this group might also have predisposed these HCWs to higher rates of infection compared with infection rates observed amongst the doctors and nurses in Somalia during the ongoing pandemic.

It is understandable that, like many other countries, Somalia suffered shortages of PPEs at the beginning of the epidemic. Owing to short supply, it was likely that health services administrators prioritised the use of the PPEs for doctors and nurses, presuming that they were at the highest risk of infection owing to their close contact and proximity to suspected patients. This might have led to a situation where hospital ancillary staff did not use PPEs or used them improperly due to lack of knowledge or training on proper infection control measures while handling patients, including use of PPEs and other protection measures, resulting in unprotected exposure amongst this group of HCWs. The other plausible explanation for the higher rate of COVID-19 infection in hospital ancillary staff is that most patients remained undiagnosed during admission to hospital settings and it could be that, owing to the shortage of doctors and nurses in countries like Somalia, this category of HCWs more frequently and casually handled the patients during admission, thereby leading to unprotected exposure.

A number of studies in Africa have also suggested that knowledge among frontline HCWs on transmission risks remains low, necessitating educational training programmes to ensure adherence to standard precautionary measures (Nkansah et al., 2020, Elhadi et al., 2020). However, many of these studies did not show a difference between different categories of HCWs, if any, in risk perception, knowledge or adherence to strict infection control/precautionary measures.

Although addressing the needs of frontline HCWs during the COVID-19 pandemic is high priority, data to better understand the exposure risk of HCWs and mode of transmission, especially on the availability and proper use of PPE and adherence of HCWs to other infection control measures, are scarce. In fragile countries where the health workforce is already understaffed, high numbers of infections in HCWs mean that hospitals have less capacity to care for patients, not only from COVID-19 but from other conditions. This situation will also disrupt essential healthcare services as there will not be enough HCWs to provide other routine services.

One of the limitations for generalising the study findings and their interpretation is the small number of HCWs included in the study. Despite this limitation, this study, the first of its kind in Somalia, stimulates policy discourse on improving and sustaining all categories of HCWs’ knowledge, perception and attitude towards standard infection prevention and control (IPC) measures across all healthcare facilities, irrespective of presentation or diagnosis of the patient, even in fragile settings like Somalia. The policy should also include administrative controls, such as establishing IPC committees in all large hospitals, frequently assessing adherence of HCWs to IPC measures, which should be inclusive of ancillary hospital staff. This will also require policy adjustment, proper training and competency in educating all categories of HCWs in Somalia to reduce exposure to transmissible diseases caused by high-threat pathogens and other novel respiratory viruses such as COVID-19. The policy should include the ancillary hospital staff because, as in countries with limited resource settings, these categories of HCWs frequently come into close contact with patients, more often so than doctors and nurses, owing to the shortage of doctors and nurses in such settings. While the country considers the roll out of COVAX for HCWs, these categories of hospital ancillary staff should also be given priority consideration for vaccination during the first phase, as they are the frontline HCWs in fragile countries like Somalia working as the major defence against COVID-19. The health and safety of all categories of HCWs must be protected in such settings to sustain public health and recoveries.

Conflict of interest

None declare.

Funding source

None.

Ethical approval

Not applicable. The use of this surveillance dataset for outbreak analysis did not need ethical approval.

Footnotes

The health workforce density in Somalia is 0.11 health workers (doctors, nurses and midwives) per 1000 population against a UHC requirement of 4.45 per 1000 by 2030.

References

- Ahmed Mohammed A.M., Colebunders R., Nelson J., Fodjo S. Evidence for significant COVID-19 community transmission in Somalia using a clinical case definition. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;98:206–207. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed Mohammed A.M., Siewe Fodjo J.N., Gele A.A., Farah A.A., Osman S., Guled I.A. COVID-19 in Somalia: adherence to preventive measures and evolution of the disease burden. Pathogens. 2020;9:735. doi: 10.3390/pathogens9090735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay S., Baticulon R., Kadhum M., Alser M., Ojuka D., Badereddin Y. Infection and mortality of healthcare workers worldwide from COVID-19: a scoping review. MedRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.06.04.20119594. 2020.06.04.20119594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhadi M., Msherghi A., Alkeelani M., Zorgani A., Zaid A., Alsuyihili A. Assessment of healthcare workers’ levels of preparedness and awareness regarding Covid-19 infection in low-resource settings. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;103:828–833. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homepage - GHS Index. https://www.ghsindex.org/ n.d. (Accessed 1 November 2020).

- Nkansah C., Serwaa D., Adarkwah L.A., Osei-Boakye F., Mensah K., Tetteh P. Novel coronavirus disease 2019: knowledge, practice and preparedness: a survey of healthcare workers in the Offinso-North District, Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35 doi: 10.11604/pamj.supp.2020.35.2.23644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sim M.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: major risks to healthcare and other workers on the front line. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77:281–282. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2020-106567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Lancet COVID-19: protecting health-care workers. Lancet. 2020;395:922. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30644-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wadvalla B.A. How Africa has tackled covid-19. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]