Graphical abstract

Keywords: Dual-frequency, Acoustic cavitation bubble, Pressure forces work, Heat diffusion, Reactions heat, Condensation

Highlights

-

•

Energetic behavior of stable cavitation bubble is analyzed under dual-frequency ultrasound.

-

•

High-energy stable cavitation is compared with bubbles non-active in sonochemistry.

-

•

Pressure forces work is the major energetic input during the bubble oscillation lifetime.

-

•

The main energetic loss is due to heat transfer by diffusion.

-

•

Energy loss accompanying water condensation results in non-activity in sonochemistry.

Abstract

The acoustic cavitation bubble as an open energetic system is the seat of conversion of various forms of energy accompanying the bubble oscillation. The energy conversion would explain specific dynamical, thermal and kinetical behaviors. In the present paper, the energy balance related to a stable bubble irradiated by dual-frequency field is simulated numerically and interpreted in accordance with the phenomena occurring inside it. The study particularly focuses on the comparison of the energetic behavior of high-energy stable cavitation with bubbles that are non-active in sonochemistry, submitted to couples of 35, 140, 300 and 515 kHz. The simulation results revealed that pressure forces work is the major energetic input during the bubble oscillation lifetime, while the main energetic loss comes from heat transfer by diffusion and enthalpy loss accompanying water condensation. Besides, high rates of condensation of water molecules and low amounts of accumulated energy inside the bubble volume were identified as the key factors preventing the achievement of the sonochemical activity threshold.

Nomenclature

- μ

Dynamic viscosity (Pa s)

- ρ

Density (kg/m3)

- σ

Surface tension (N/m)

Stoichiometric coefficient related to the kth species in the ith reaction

- α

Accommodation coefficient

- ϕ

Phase difference (rad)

- ΔHi

Reaction heat of the ith reaction (J/mol)

Pre-exponential factor of the ith reaction (m3/mol s) for two body reaction, (m6/mol2 s) for three body reaction

- c

Sound celerity (m/s)

Concentration of the kth species (mol/m3)

Concentration of the kth species due to chemical kinetics (mol/m3)

Concentration of the kth species due to physical kinetics (mol/m3)

Isochoric heat capacity of bubble content (J/mol.K)

Energy flow of heat diffusion (W)

Energy flow of heat transferred with condensed and evaporated water (W)

Energy flow of pressure forces work (W)

Energy flow of reaction heat (W)

Activation energy of the ith reaction

- f

Frequency (Hz)

Kinetic constant of the ith reaction (m3/mol s) for two body reaction, (m6/mol2 s) for a three body reaction

- M

Molar mass (g/mol)

- n

Molar amount (mol)

Evaporation-condensation rate of water (kg/m2 s)

Acoustic amplitude (Pa)

Partial pressure of water (Pa)

Saturating vapor pressure (Pa)

Acoustic pressure (Pa)

- R

Bubble radius (m)

Bubble wall velocity (m/s)

Bubble wall acceleration (m/s2)

Reaction rate of the ith reaction (mol/s m3)

Ideal gas constant (J/mol K)

Area of the bubble wall (m2)

- T

Temperature within the bubble (K)

- t

Time (s)

Volume of the bubble (m3)

1. Introduction

Ultrasound is acoustic energy in the form of waves having a frequency above the human hearing range, i.e., almost above 20 kHz [1]. One of the most interesting applications of ultrasonic waves is their indirect chemical effect, known as “sonochemistry” [2]. Sonochemistry is a mean of introducing energy in a medium to bring about a chemical change [3], not through a direct interaction between the reacting species and the irradiating wave, but via the formation of a cavitation bubble that accumulates enough energy during its oscillation to stimulate chemical species interaction and produce oxidants. During bubble expansion and compression, pressure forces are exerted on the bubble wall [4], inducing a work that participates in the energy balance of the bubble. The acoustic bubble, considered as an open system of varying volume in function of time, knows as well an exchange of heat with the external medium resulting of two sources. Firstly, the heat transfer by diffusion due to temperature gradient between both sides of bubble wall [5], and secondly, the amount of energy transported with the flow of water molecules migrating from and to the bulk of the bubble as a consequence of the non-equilibrium of evaporation and condensation phenomenon at the gas-liquid interface [6]. In addition, a set of elementary reactions is activated inside the bubble, thanks to the accumulation of energy [7], [8], and consequently, a considerable amount of heat is absorbed and released according to the thermal character of the evolving reactions [9]. The conversion of the various forms of energy, i.e., works of pressure forces, diffused heat, transported enthalpy with evaporated and condensed water and reactions heat, would create at each instant a certain variation of the amount of accumulated energy, which affects at its turn the temperature inside the bubble.

Usually, energetic studies of sonochemistry focuses on ratios of the macroscopic energy consumption to the produced yields [10], [11], [12]. Though the macroscopic acoustic energy is indeed responsible of the microscopic phenomena of acoustic cavitation and hence the sonochemical activity, the macroscopic energy studies allow techno-economic assessment of the performance of a given sonochemical process or reactor configuration [13], [14], but do not bring any information regarding the forms of energy that evolve at the microscopic scale. On the other hand, few attempts were carried toward investigating the microscopic energy forms and their evolution at single bubble scale [4], [15]. For instance, Merouani et al. [15] analyzed numerically the variation of the internal energy power estimated over one acoustic cycle, in function of the physical and acoustic conditions applied on the liquid medium. Vichare et al. [4] followed a quasi-similar methodology, however, they considered the total bubble lifetime rather than one acoustic cycle, to evaluate the average internal energy power. However, the models of Vichare et al. [4] and Merouani et al. [15] were based on simplistic hypothesis assuming that the internal energy is exclusively affected by the variation of pressure forces work.

Besides, dual-frequency excitation has been explored in numerous researches in the last years, without leading to a generalized consensus on its effect. To illustrate, Tatake and Pandit [16] have experimentally examined the effect of introducing a second wave in a sonochemical reactor and proved that this configuration would provide a better distribution of cavities in the reactor volume and then lead to its optimal use. Nevertheless, Son et al. [17] demonstrated experimentally a negative impact due to the dual-frequency; as compared to the mono-frequency; when combining a 20 kHz wave to a second wave of 200–500 kHz. Some other works investigated numerically the sonochemical effects of the dual-frequency excitation. For instance, Tatake and Pandit [16] supported their experimental findings by a numerical model of a single cavitation bubble, however, the dynamical behavior was described by the basic equation of Rayleigh-Plesset and covered only the couple of 20 and 35 kHz. Kanthale et al. [18], [19] adopted the same approach as Tatake and Pandit [16], with employing Tomita and Shima equation [20] to treat a larger scope of frequency couples.

In a detailed numerical study carried by our research group on the bubble dynamics under a dual-frequency excitation [21], bubbles of 2 µm of ambient radius demonstrated stable oscillation under mono-frequency excitation of 35, 140, 300 and 515 kHz and dual-frequency excitations with the six couples resulting from their combinations as shown in Table 1. However, the study of their sonochemical activity proved that only bubbles submitted to mono-frequency excitations of 140 and 300 kHz and dual-frequency excitation associating 35 and 140 kHz attained sonochemical activity threshold [22] fixed conventionally at 108 molecules/second⋅bubble [23]. Based on both previous results, the bubbles undergoing an acoustic irradiation of 140 and 300 kHz, or the couple (35, 140 kHz) are qualified as high-energy stable cavitation, and in contrast, the other bubbles are described as stable but non-active in sonochemistry, as reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the dynamic and kinetic characteristics of a bubble of 2 µm of ambient radius, submitted to dual-frequency acoustic field of acoustic amplitude of 1.5 atm, based on Kerboua et al. [21], [22].

| Frequency (kHz) | 35 | 140 | 300 | 515 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry | High-energy stable cavitation | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry |

| 140 | High-energy stable cavitation | High-energy stable cavitation | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry |

| 300 | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry | High-energy stable cavitation | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry |

| 515 | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry | Stable, non-active in sonochemistry |

In the present study, it is believed that a deeper and more realistic understanding of the forms of energy that evolve at the microscopic scale may explain the observations related to shape stability [24], sonochemical yields [25] and positive or negative effects of dual-frequency excitation [26], [27]. The category of high-energy stable cavitation indicated in Table 1, based on the previous study of our research group, is the subject of the energetic analysis intended by the present study. The energy balance related to single acoustic bubble is particularly interesting in the case of high-energy stable cavitation [28], since these bubbles have just enough energy to be the seat of sonochemical activity, but not enough energy to break apart at extreme contraction. They are consequently sonochemically active and live longer than transient cavitation owing to their stable oscillation [29]. In the present paper, we suggest to closely analyze the energy balance of stable cavitation bubble submitted to dual-frequency sonication under oxygen atmosphere, in order to figure out the predominant energetic mechanisms governing the shape stability and the achievement of the sonochemical activity threshold, leading to high-energy stable cavitation. Thus, the various forms of energy involved in the energy balance are quantified versus time, and their mutual compensation is examined to explain, on one hand, the evolution of temperature inside the bubble during collapse in the case of stable oscillation, and on the other hand, the observed sonochemical activity in the case of high-energy stable cavitation. Practically, the present study investigates the relationship between the bubble dynamics and the thermal behavior, the thermal behavior and the sonochemical activity, as well as the energy and mass balances, in the case of dual-frequency sonication. This investigation would explain several contradictory experimental findings retrieved in the literature.

2. Computational methodology

The radial dynamics of the cavitation bubble is described by the modified Keller-Miksis equation expressed as shown in Eq. (1).

| (1) |

The acoustic pressure applied by the wave at each instant is schematized in Eq. (2) as a sum of two synchronized sinusoidal signals having and as respective frequencies. We opted in this formulation for a null delay in the irradiation by both signals, i.e., the phase difference appearing in Eq. (2) was set to zero. This choice is justified by the results of Tatake and Pandit [16] who demonstrated a maximum sonochemical efficiency in the absence of a phase difference.

| (2) |

Moreover, both waves composing the dual-frequency irradiation are supposed to exert similar values of maximum acoustic power on the crossed liquid medium, they are characterized by common acoustic amplitude that equals [21], [30], [31]. Consequently, the maximum acoustic amplitude due to dual-frequency excitation cannot exceed , which eliminates the eventuality of acoustic pressure amplification when explaining the effect of frequencies association, as compared to mono-frequency excitation.

The acoustic cavitation bubble is characterized by its ambient radius, its value determines either the bubble would undergo a stable oscillation or lose its spherical shape and disintegrate into daughter bubbles after few cycles [24], [32]. In this study, we imposed two specific criteria in order to lead up to comparable results. Firstly, we opted for the selection of a common value of to simulate the bubble dynamics under various studied frequencies. Thus, a bubble exposed to a dual-frequency wave associating and is supposed to have the same ambient radius as under their isolated effects. Secondly, the value of this ambient radius was selected within the shape stability zones according to the diagrams elaborated by Yasui et al. [23], [33] and Toegel [34], with respect to Hilgenfeldt et al. [35] results. The findings of aforementioned studies have been synthetized in Fig. 1 that indicates the shape stability limits under an acoustic amplitude varying from 1.25 to 1.50 atm and frequencies of 35, 140, 300 and 515 kHz. In the present paper, and in accordance with the previous specific criteria, the four frequencies mentioned above are considered at an acoustic amplitude of 1.5 atm, assuming an initial bubble radius of 2 µm. These bubbles demonstrated effectively stable oscillation under mono and dual-frequency excitations resulting from the aforementioned acoustic conditions, as shown in a detailed dynamics study of our research group [21]. Moreover, the study of the sonochemical activity [36] of these bubbles proved that bubbles submitted to the couple (35, 140 kHz) are sonochemically active [23], this category is qualified as high-energy stable cavitation [28].

Fig. 1.

Diagram of shape stability of an acoustic cavitation bubble undergoing an acoustic wave of an amplitude varying from 1.25 to 1.5 atm and a frequency of 35, 140, 300 and 515 kHz.

Water and oxygen molecules initially present in the bulk of the bubble interact according to a set of chemical reactions giving rise to a number of oxidants such as , and . The detailed elementary reactions expected to occur inside the bubble are reported in Table 2 and have been already presented in previous papers [37], [38]. The mass balance related to each one of the reactants and products is schematized in Eq. (3). The variation in the molar yield of each species is explained by the chemical and physical kinetics.

| (3) |

Table 2.

Adopted scheme of the possible reactions occurred inside an O2/H2O collapsing bubble. M is the third body. Subscript “f” denotes the forward reaction and “r” denotes the reverse reaction. A is in (m3/mol s) for two body reaction and (m6/mol2 s) for three body reaction [40].

| No. | Reactions | Afi | bfi | Eafi/Rg (K) | Ari | bri | Eari/Rg (K) | ΔHi (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | H + O2 ⇌ O + •OH | 1.92 × 108 | 0 | 8270 | 7.18 × 105 | 0.36 | −342 | 69,17 |

| 2 | O + H2 ⇌ H• + •OH | 5.08 × 10−2 | 2.67 | 3166 | 2.64 × 10−2 | 2.65 | 2245 | 8,23 |

| 3 | •OH + H2 ⇌ H• + H2O | 2.18 × 102 | 1.51 | 1726 | 1.02 × 103 | 1.51 | 9370 | −64,35 |

| 4 | •OH + •OH ⇌ H2O + O | 2.1 × 102 | 1.4 | 200 | 2.21 × 103 | 1.4 | 8368 | −72,59 |

| 5 | H2 + M ⇌ H• + H• + M Coef. H2: 2.5, H2O: 16.0 |

4.58 × 1013 | −1.4 | 52,500 | 2.45 × 108 | −1.78 | 480 | 444,47 |

| 6 | O + O + M ⇌ O2 + M Coef. H2: 2.5, H2O: 16.0 |

6.17 × 103 | −0.5 | 0 | 1.58 × 1011 | −0.5 | 59,472 | −505,4 |

| 7 | O + H• + M ⇌ •OH + M Coef·H2O: 5.0 |

4.72 × 105 | −1.0 | 0 | 4.66 × 1011 | −0.65 | 51,200 | −436,23 |

| 8 | H• + •OH + M ⇌ H2O + M Coef. H2: 2.5, H2O: 16.0 |

2.25 × 1010 | −2.0 | 0 | 1.96 × 1016 | −1.62 | 59,700 | −508,82 |

| 9 | H• + O2 + M ⇌ HO2• + M Coef. H2: 2.5, H2O: 16.0 |

2.00 × 103 | 0 | −500 | 2.46 × 109 | 0 | 24,300 | −204,8 |

| 10 | H• + HO2• ⇌ O2 + H2 | 6.63 × 107 | 0 | 1070 | 2.19 × 107 | 0.28 | 28,390 | −239,67 |

| 11 | H• + HO2• ⇌ •OH + •OH | 1.69 × 108 | 0 | 440 | 1.08 × 105 | 0.61 | 18,230 | −162,26 |

| 12 | O + HO2• ⇌ O2 + •OH | 1.81 × 107 | 0 | −200 | 3.1 × 106 | 0.26 | 26,083 | −231,85 |

| 13 | •OH + HO2• ⇌ O2 + H2O | 1.45 × 1010 | −1.0 | 0 | 2.18 × 1010 | −0.72 | 34,813 | −304,44 |

| 14 | HO2• + HO2• ⇌ O2 + H2O2 | 3.0 × 106 | 0 | 700 | 4.53 × 108 | −0.39 | 19,700 | −175,35 |

| 15 | H2O2 + M ⇌ •OH + •OH + M Coef. H2: 2.5, H2O: 16.0 |

1.2 × 1011 | 0 | 22,900 | 9.0 × 10−1 | 0.90 | −3050 | 217,89 |

| 16 | H2O2 + H• ⇌ H2O + •OH | 3.2 × 108 | 0 | 4510 | 1.14 × 103 | 1.36 | 38,180 | −290,93 |

| 17 | H2O2 + H• ⇌ H2 + HO2• | 4.82 × 107 | 0 | 4000 | 1.41 × 105 | 0.66 | 12,320 | −64,32 |

| 18 | H2O2 + O ⇌ •OH + HO2• | 9.55 | 2 | 2000 | 4.62 × 10−3 | 2.75 | 9277 | −56,08 |

| 19 | H2O2 + •OH ⇌ H2O + HO2• | 1.00 × 107 | 0 | 900 | 2.8 × 107 | 0 | 16,500 | −128,67 |

| 20 | O3 + M ⇌ O2 + O + M Coef. O2: 1.64 Coef. O2: 1.63, H2O: 15 |

2.48 × 108 | 0 | 11,430 | 4.1 | 0 | −1057 | 109,27 |

| 21 | O3 + O ⇌ O2 + O2 | 5.2 × 106 | 0 | 2090 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −396,14 |

| 22 | O3 + •OH ⇌ O2 + HO2• | 7.8 × 105 | 0 | 960 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −164,92 |

| 23 | O3 + HO2• ⇌ O2 + O2 + •OH | 1 × 105 | 0 | 1410 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −121,92 |

| 24 | O3 + H• ⇌ HO2• + O | 9 × 106 | 0.5 | 2010 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −135,65 |

| 25 | O3 + H• ⇌ O2 + •OH | 1.6 × 107 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | −96,2 |

Applying Eq. (3) to the chemical species involved in the chemical schema results in Eqs. (4), (5).

| (4) |

| (5) |

and represent the kinetic constants for the forward and backward reactions, respectively, expressed in function of temperature according to Arrhenius formula presented in Eq. (6).

| (6) |

The thermodynamic parameters describing the bubble state at each instant are governed by an energetic balance summarized in Eq. (7).

| (7) |

In the present study, we give a special interest to the evaluation of the energetic terms involved in this balance, in order to figure out the conversion of energy inside high-energy stable cavitation undergoing dual-frequency excitation. We then estimate the energy flow due to the pressure forces work exerted on the bubble wall , expressed in Eq. (8).

| (8) |

We also assess the flow of absorbed or released reaction heat , formulated in Eq. (9).

| (9) |

We finally evaluate the flow transferred by heat diffusion using Eq. (10), and the flow of transfer of enthalpy transported with evaporated and condensed water molecules at the bubble interface , as indicated in Eq. (11).

| (10) |

| (11) |

The thermal behavior of the acoustic bubble is explained by the variation of its internal energy expressed in Eq. (12). The internal energy of the bubble evolves according to the variation and conversion of different forms of energy expressed in Eqs. (8), (9), (10), (11) as mentioned previously in Eq. (7).

| (12) |

represents the partial internal energy of the ith species present in the bubble volume in a molar quantity equal to .

The mass and energy balances, i.e., Eqs. (4), (5) and (7), and the dynamics equation, i.e., Eq (1), constitute a system of dependent nonlinear differential equations that can be reduced to first order, and then resolved using the Runge-Kutta 4th order numerical algorithm. The resolution of this system offers a quantity of data regarding the bubble radius evolution, the bubble wall velocity, the temperature and pressure inside the bubble, the mass variation and consequently the quantification of the different forms of energy all along the bubble oscillation. The simulations are conducted over a duration of 100 µs, this simulation time proved sufficient to obtain a representative dynamical response of the bubble to the excitation field, and offers a convenient readability especially at short acoustic periods, i.e., under 300 and 515 kHz.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Evolution of energy flows, their resulting balances and the accumulated energy

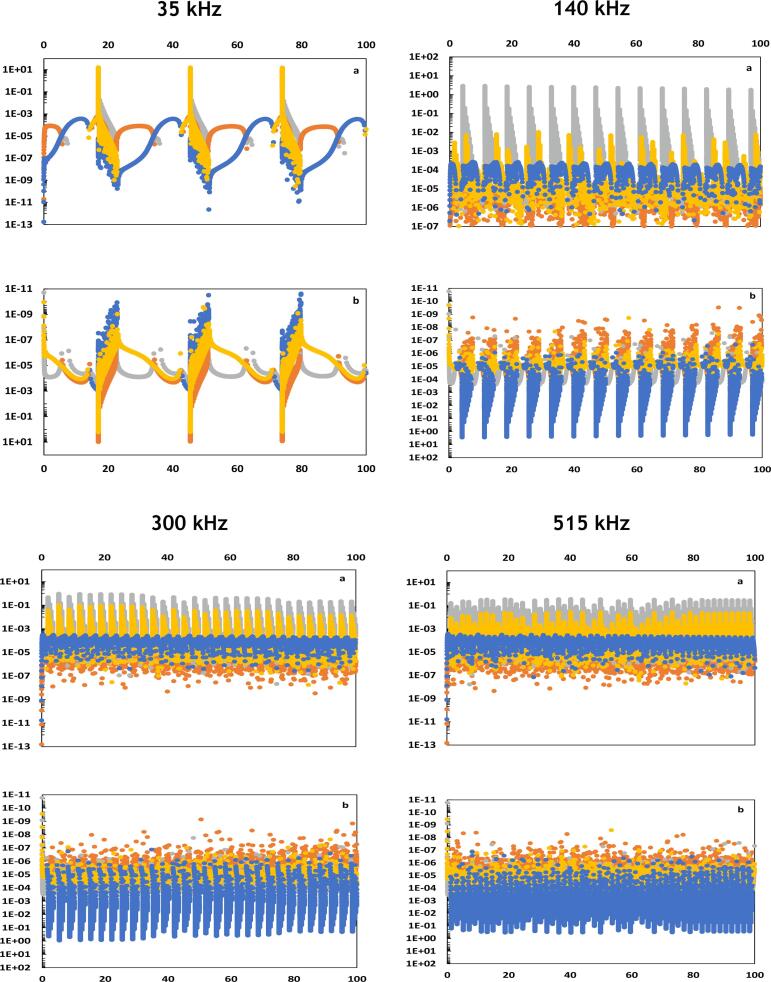

In the present study, the flows related to the various forms of energy involved in the energy balance are quantified in an attempt to figure out the specific energetic behavior of stable bubbles that are active in sonochemistry, i.e., the high-energy stable cavitation reported in Table 1 [21], [36]. We proceed to the analysis of the simultaneous evolutions of the flows of energy and , according to the couples of frequencies formed by combining 35, 140, 300 and 515 kHz, as reported in Fig. 2. All the graphical representations denoted “a” in Fig. 2 represent the evolution of energy flows impacting positively the term . In contrast, the graphical representations denoted “b” refer to the evolution of flows impacting negatively the term .

Fig. 2.

Simultaneous evolutions of energetic powers , , and (vertical axis in W) in function of time (horizontal axis in µs) for various cases of mono and dual-frequency excitations. refers to pressure forces work (yellow line), refers to reactions heat (orange line), refers to heat diffusion (blue line) and refers to heat transfer with evaporated and condensed water molecules (grey line). Figures (a) represent the energetic powers of positive intakes while figures (b) are those of negative intakes in the variation of bubble temperature. Figures with higher size and resolution are available in the Supplementary material. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

The analysis of Fig. 2 is performed following two stages. In the first stage of the analysis, the energy flows related to the different forms of energy are particularly compared at their maximums.

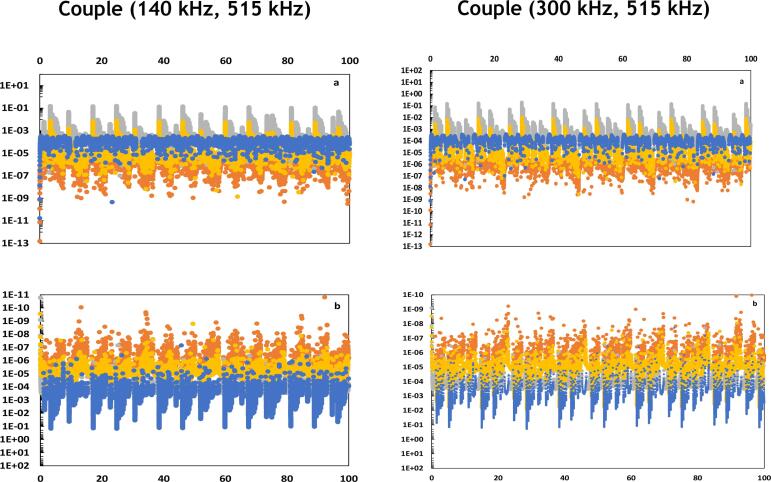

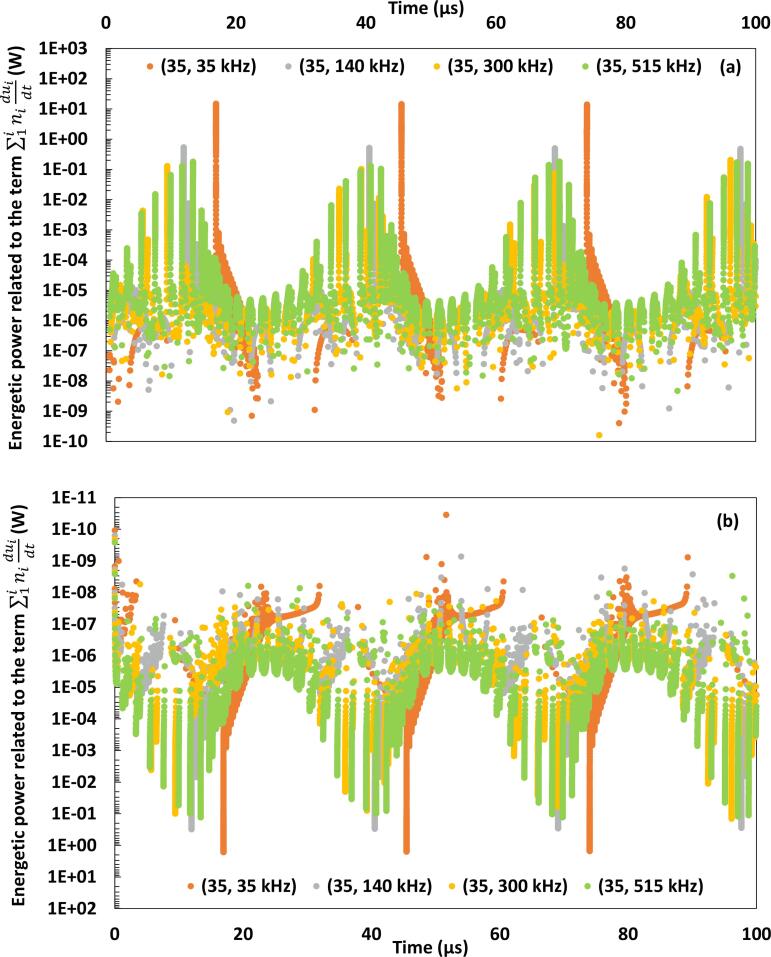

In the second stage of the analysis of Fig. 2, the results of the conversion of the different forms of energy involved in the energy balance are linked to the evolution of accumulated energy expressed through the term . Fig. 3 represents the positive (a) and negative (b) variations of the term estimated under dual-frequency excitations associating 35 kHz to 35, 140, 300 and 515 kHz. The other frequency combinations are covered in the Supplementary material. The areas delimited by the graphical scatters reported in Fig. 3 constitute the variation of the internal energy, which is responsible of the temperature evolution in function of time. Fig. 2, Fig. 3 are discussed simultaneously. It is important to notice that the case of a mono-frequency excitation with a frequency and an acoustic amplitude is equivalent to a dual-frequency excitation associating to , with a common amplitude .

Fig. 3.

Positive (a) and negative (b) variations of the term at the basic frequency of 35 kHz in function of time. The variations related to the other basic frequencies of 140, 300 and 515 kHz in function of time are available in the Supplementary material.

The maximum values of energetic flows reported in Fig. 2 allow the identification of the predominant energy forms impacting positively or negatively the internal energy of the bubble. It is observed that the compressive work of pressure forces and the heats of exothermic reactions play the major role in the augmentation of the internal energy of the bubble and hence the increase of temperature. In contrast, the heat diffusion during collapse is the principal source of diminution of the internal energy and consequently temperature decrease. Fig. 2 demonstrates as well that some energy flows, though attaining high values, vary in form of punctual spikes, leading to a timely short and restrained impact. Thus, the time integration of these flows results in low amounts of energy. This is the case of heats of exothermic reaction, which are characterized by energy flows of high values but very limited duration (Fig. 2a). In contrast, the heats of endothermic reactions show moderated values of energy flows but of longer action time (Fig. 2b). To illustrate, under a mono-frequency of 300 kHz, both previous effects last 9% and 91% of time, respectively. Thereby, we consider in the following discussion carried out based on the values of the basic frequency , both the value and the duration of the energy flow in order to assess the resulting energy impact. The main energetic observations revealed by Fig. 2, Fig. 3 are reported in Table 3 in order to summarize the predominant effects behind the High Energy Stable Cavitation, as shown in Table 1.

Table 3.

Summary of the main energetic characteristics of a bubble of 2 µm of ambient radius, submitted to dual-frequency acoustic field of maximum amplitude of 1.5 atm, based on the present study.

| Frequency (kHz) | 35 | 140 | 300 | 515 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 35 | High energy loss due to condensation rate | High energy gain due to compressive work & exothermic reactions | High mass loss due to high condensation rate | High energy gain due to compressive work High energy loss due to heat diffusion |

| 140 | High energy gain due to compressive work & exothermic reactions | High energy gain due to compressive work & exothermic reactions | High energy loss due to heat diffusion & condensation rate | Low energy gain due to compressive work |

| 300 | Low energy gain due to compressive work & exothermic reactions | Low energy gain due to compressive work & exothermic reactions | Low mass loss due to condensation rate | Low energy gain due to compressive work |

| 515 | Very low energy gain due to compressive work & exothermic reactions | Very low energy gain due to compressive work & exothermic reactions | Very low energy gain due to compressive work & exothermic reactions | High energy gain due to compressive work High energy loss due to heat diffusion |

Cases shown in bold refer to high energy stable cavitation.

3.2. Basic frequency of 35 kHz

When fixing the basic frequency to 35 kHz, Fig. 2 shows that coupling 35 kHz to higher frequencies of 140, 300 and 515 kHz, respectively, results in three particular trends of variation of energy flows. Firstly, the positive energetic intakes gradually decrease. To illustrate, the flow of the pressure forces work passes from 8.2 W under a 35 kHz excitation to 0.3, 0.085 and 0.093 W when coupling it to 140, 300 and 515 kHz, respectively. Secondly, the negative energetic intakes, except those related to heats of endothermic reactions, seem to follow a decreasing trend as well, the bubble loses less and less energy with the increase of the second frequency associated to 35 kHz. Thirdly and exclusively under a mono frequency irradiation of 35 kHz, it is observed that the most important energetic loss is due to the heat transferred with the condensed water. Its thermal flow reaches 6.2 W, while it drops to 1 × 10−3, 3.6 × 10−4 and 3.3 × 10−4 W when coupling 35 kHz to 140, 300 and 515 kHz, respectively.

The previous observations are in accordance with the variations of accumulated energy flow reported in Fig. 3. Indeed, the comparison of the areas delimited by the scatters of the term related to 35 kHz and the couple (35, 140 kHz) demonstrates a higher value for the couple (35, 140 kHz) around the instant of strong collapse, which is equivalent to higher maximum temperatures. This is explained by the amount of the energy loss accompanying water condensation under 35 kHz, lowering severely the accumulated energy under this frequency as compared to the couple (35, 140 kHz), in spite of the considerable energetic gain due to the compressive work. On the other hand, Fig. 3(a) indicates that the areas related to the couples (35, 300 kHz) and (35, 515 kHz) are smaller than under the couple (35, 140 kHz). This trend is explained by the predominance of the compressive work as compared to the other energy forms, which makes the accumulation of energy under (35, 140 kHz) more important than under (35, 300 kHz) and (35, 515 kHz). This finding is reported in Table 3 and would explain why the bubble reaches the sonochemical activity barrier specifically under this irradiation compared to the mono-frequency excitation of 35 kHz and the couples (35, 300 kHz) and (35, 515 kHz), as indicated in Table 1.

3.3. Basic frequency of 140 kHz

With a basic frequency of 140 kHz, it is observed from Fig. 2 that when coupling 140 kHz to a lower frequency, i.e., 35 kHz, the positive energetic intakes due to the compressive work and the heats of the exothermic reactions increase. Indeed, the maximum energy flow of compressive work passes from 0.009 to 0.3 W, while the maximum energy flow due to exothermic reactions increases from 1.74 to 1.95 W. In parallel, the heat losses due to condensation and pressure forces work exerted during expansion are increased, while heats of endothermic reactions and diffusion are both reduced. The most important decrease is related to heat diffusion, its maximum energy flow passes from 2.66 to 2.20 W. On the other hand, Fig. 3 (Supplementary material) demonstrates that the area delimited by the scatter representing the flow of under (140, 35 kHz) until the instant of strong collapse is greater than that retrieved with 140 kHz. The explanation would come from the global augmentation in the positive intakes and the diminution of the heat loss by diffusion when passing from 140 kHz to (140, 35 kHz), as observed previously.

Besides, coupling 140 kHz to higher frequencies results in the diminution of both positive and negative intakes of energy. Energy flows of compressive work, exothermic reactions and heat losses, except those due to endothermic reactions, demonstrate indeed decreasing trends. However, the reduction in energy gain seems to take the upper hand, conducting to smaller and smaller accumulation of energy, shown by the areas of Fig. 3 (Supplementary material), when passing from a mono frequency excitation of 140 kHz, to the couples (140, 300 kHz) and (140, 515 kHz), respectively.

It is worthy to note that with a basic frequency of 140 kHz, the amount of accumulated energy is in good agreement with the sonochemical activity reported in Table 1. According to Table 2, the single acoustic cavitation bubble is active in sonochemistry either under dual-frequency excitation of (140, 35 kHz) or the mono-frequency excitation of 140 kHz, both cases conduct to the highest values of accumulated energy as reported above.

3.4. Basic frequency of 300 kHz

Similar analysis is carried out with a basic frequency of 300 kHz. Coupling 300 kHz to lower frequencies induces an increase in the energy flows related to compressive work and exothermic reactions, but also an augmentation of energy flows related to heat loss due to pressure forces work during expansion, diffusion and water molecules condensation. This effect is much more noticeable as the second frequency is low. On the other hand, passing from 300 kHz to the couple (300, 515 kHz) seems to induce the opposite variation trends, the energy flows related to compressive work, exothermic reactions but also diffusive loss, expansion work and endothermic reactions demonstrate a clear decrease. The energy balance in then governed by the predominant form of energy. Besides, Fig. 3 (Supplementary material) shows an increase of the area delimited by the scatter when passing from (300, 515 Hz) to 300 kHz, then (300, 140 kHz) and finally (300, 35 kHz), indicating that the compressive work plays a preponderant role in the energy balance. The case of basic frequency of 300 kHz is particularly interesting since sonochemical activity does not seem to follow the same trend as accumulated energy. Curiously, 300 kHz is the only case achieving the sonochemical activity barrier and leading to the High Energy Stable Cavitation, as shown in Table 1, but it does not lead to the highest accumulation of energy. In an attempt to explain what particularly stimulates the sonochemical activity under 300 kHz, we suggest to simultaneously inspect energy and mass balances. It appears that mass loss of water molecules by condensation is higher when passing from 300 to (300, 140 kHz) and (300, 35 kHz). This observation is coherent with the augmentation of energy loss due to condensed water noticed previously. Thus, though the highest accumulation of energy is recorded under (300, 35 kHz), it is accompanied by the highest condensation rate of water molecules, which reduces the amount of reactant available at the beginning of the collapse phase. 300 kHz leads then to the optimal balance of accumulated energy and available amount of water molecules inside the bubble volume, which would explain the sonochemical activity reached exclusively under this irradiation.

3.5. Basic frequency of 515 kHz

Coming to 515 kHz, several particular trends are observed. Firstly, the mono-frequency irradiation results in the highest energy flow of compressive work, its maximum value is estimated to 0.0207 W. This value is decreased when coupling 515 kHz to 300 or 140 kHz, but increase again when coupling 515 kHz to 35 kHz, it reaches then 0.093 W. secondly, the mono-frequency excitation of 515 kHz induces high energy flow due to heat loss by diffusion during the collapse, its maximum equals 0.3 W. This value decreases to 0.14 W when coupling 515 to 300 kHz, then to 0.085 W when coupling 515 kHz to 140 kHz. Contrariwise, the couple (515, 35 kHz) generates the highest loss by diffusion attaining 1.32 W. Fig. 3 (Supplementary material) demonstrates that as a result to the aforementioned balances, the couple (515, 35 kHz) induces the highest accumulation of energy within the bubble volume, followed by the mono-frequency irradiation of 515 kHz. However, both acoustic excitations do not conduct to sufficient energy so as the bubble becomes active in sonochemistry, as already reported in Table 2.

3.6. Effect of the energy balance on the thermal behavior

In order to confirm the previous results regarding the accumulated energy within the bubble volume, we propose to follow the evolution of the bubble temperature as a function of simulation time for different cases of mono and dual-frequency excitations. The obtained graphical plots have been sorted according to the basic frequency value, as shown in Fig. 4. This figure demonstrates that for a basic frequency of 35 kHz, the most important value of maximum temperature is recorded with the couple (35, 140 kHz), it decreases gradually when elevating the second frequency to 300 then 515 kHz, respectively. For a basic frequency of 140 kHz, the highest value of temperature is encountered under a mono-frequency irradiation. Coupling 140 kHz to any of the treated frequencies induces a drop of the maximum temperature, is even more reduced as the second frequency increases. On the other hand, coupling 300 kHz to a wave of lower frequency generates an increase in maximum temperature while the opposite is observed when coupling it to higher frequencies. Finally, with a basic wave of 515 kHz, the couple (515, 35 kHz) is the only case conducting to a value of more important than that obtained with the mono-frequency irradiation of 515 kHz. The results reported in Fig. 4 are in exact agreement with the evolution of the term presented in Fig. 3 (Supplementary material). It is noteworthy to mention that in the specific case of dual-frequency excitation, there is no correlation between the compression ratio and the temperature, at the opposite of what is usually applicable under mono-frequency excitation. Indeed, though several previous studies proved that bubble submitted to mono-frequency ultrasonic field shows a proportionality between and compression ratio [39], this is no longer applicable when passing to dual-frequency excitation. For instance, in spite of the extreme compression ratio attained under 35 kHz and exceeding 500, the energetic balance is widely affected by the condensation phenomena, which explains the drop of temperature noticed in this case, as compared to the couple (35, 140 kHz), where the compression ratio does not exceed 50 [21].

Fig. 4.

Variation of bubble temperature in function of time at various cases of mono and dual-frequency excitation related to the basic frequencies of 35 (a), 140 (b), 300 (c) and 515 kHz (d).

4. Conclusion

The present study consists in an energy analysis aiming to identify the major forms of energy acting in the energetic balance related to a stable acoustic cavitation bubble saturated with oxygen and exchanging heat and mass with the surroundings. The effects of the different forms of energy on the thermal and sonochemical activity of the bubble are investigated as well. It was demonstrated that generally, the compressive work is the predominant source of energetic gain, while the diffusive heat represents the predominant energetic loss. However, some cases showed an exception to this finding, which explained their particular thermal and sonochemical behavior. For instance, at 35 kHz, the condensation of water molecules demonstrated to be by far the major source of heat dissipation. Consequently, in spite of the harsh dynamics conditions attained under 35 kHz and revealed by the compression ratio, the energetic balance is widely affected by the condensation phenomena, which explains the drop of temperature noticed in this case, as compared to when coupling it to 140 kHz.

In the other hand, associating a basic frequency to a higher frequency generally generates a diminution of the energy flows inducing the increase of the internal energy of the bubble, predominated by compressive work. However, this modification is usually accompanied of a decrease in energetic losses due to heat diffusion and pressure forces work during expansion, as well as an increase in heat loss due to endothermic reactions. The competition of these energy forms governs the variation of the term , and consequently the values of maximum temperatures attained during bubble collapse.

In an attempt to explain the relationship between the evolution of different forms of energy flows and sonochemical activity, the study focused on the identified cases of high-energy stable cavitation, which corresponded to stable bubbles submitted to mono-frequencies of 140 and 300 kHz and dual-frequency field of (35, 140 kHz). The energy analysis highlighted that stable bubble that are active in sonochemistry are characterized by a good compromise of the value of accumulated energy and the rate of condensed water molecules. Hence, high rates of condensation of water molecules and low amounts of accumulated energy inside the bubble volume are usually the factors preventing the achievement of the sonochemical activity threshold. Thus, one should keep in mind that, when dealing with dual-frequency excitation, harsher dynamics of bubble oscillation is not equivalent to higher collapse temperature, as well as higher temperatures during collapse are not equivalent to enhanced sonochemical activity.

As future directions for this study, examining the effect of dual-frequency sonication on the bubble-bubble interactions, the bubble size distribution, the bubble number density, the spatial distribution of bubbles within the reactor volume and the bubble lifetime would be necessary in order to model the multiple frequency sonochemical reactors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Kaouther Kerboua: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Formal analysis, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Oualid Hamdaoui: Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing - review & editing. Abdulaziz Alghyamah: Visualization, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deputyship for Research & Innovation, “Ministry of Education” in Saudi Arabia for funding this research work through the project number IFKSUHI-1441-501.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ultsonch.2021.105471.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sillanpää M. Briefs Green Chem. Sustain. 2011. Ultrasound technology in green chemistry; pp. 1–21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mason T.J. Sonochemistry: current uses and future prospects in the chemical. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A. 1999;357:355–369. doi: 10.1098/rsta.1999.0331. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Son Y. Handb. Ultrason. Sonochemistry. 2016. Advanced oxidation processes using ultrasounds technology for water and wastewater treatment; pp. 1–22. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vichare N.P., Senthilkumar P., Moholkar V.S., Gogate P.R., Pandit A.B. Energy analysis in acoustic cavitation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2000 doi: 10.1021/ie9906159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Storey B.D., Szeri A.J. A reduced model of cavitation physics for use in sonochemistry. Proc. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2001;457:1685–1700. doi: 10.1098/rspa.2001.0784. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yasui K. Effect of non-equilibrium evaporation and condensation on bubble dynamics near the sonoluminescence threshold. Ultrasonics. 1998;36:575–580. doi: 10.1016/S0041-624X(97)00107-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fitzgerald M.E., Griffing V., Sullivan J. Chemical effects of ultrasonics-“Hot spot” chemistry. J. Chem. Phys. 1956;25:926–933. doi: 10.1063/1.1743145. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Suslick K.S. The sonochemical hot spot. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 1991;89:1885–1886. doi: 10.1121/1.2029381. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerboua K., Hamdaoui O. Influence of reactions heats on variation of radius, temperature, pressure and chemical species amounts within a single acoustic cavitation bubble. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;41:449–457. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Juboori R.A., Yusaf T., Bowtell L. Energy conversion efficiency of pulsed ultrasound. Energy Proc. 2015;75:1560–1568. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2015.07.340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Toma M., Fukutomi S., Asakura Y., Koda S. A calorimetric study of energy conversion efficiency of a sonochemical reactor at 500 kHz for organic solvents. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011;18:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussain M.N., Al Kaabi S., Janajreh I. Optimizing acoustic energy for better transesterification: a novel sono-chemical reactor design. Energy Proc. 2017;105:544–550. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2017.03.354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhirud U.S., Gogate P.R., Wilhelm A.M., Pandit A.B. Ultrasonic bath with longitudinal vibrations: a novel configuration for efficient wastewater treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2004;11:143–147. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sivakumar M., Tatake P.A., Pandit A.B. Kinetics of p-nitrophenol degradation: effect of reaction conditions and cavitational parameters for a multiple frequency system. Chem. Eng. J. 2002;85:327–338. doi: 10.1016/S1385-8947(01)00179-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merouani S., Hamdaoui O., Rezgui Y., Guemini M. Energy analysis during acoustic bubble oscillations: relationship between bubble energy and sonochemical parameters. Ultrasonics. 2014;54:227–232. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatake P.A., Pandit A.B. Modelling and experimental investigation into cavity dynamics and cavitational yield: influence of dual frequency ultrasound sources. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2002;57:4987–4995. doi: 10.1016/S0009-2509(02)00271-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Son Y., Lim M., Cui M., Khim J. Estimation of sonochemical reactions under single and dual frequencies based on energy analysis. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 2010;49:2–6. doi: 10.1143/JJAP.49.07HE02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanthale P.M., Gogate P.R., Pandit A.B. Modeling aspects of dual frequency sonochemical reactors. Chem. Eng. J. 2007;127:71–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2006.09.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanthale P.M., Brotchie A., Ashokkumar M., Grieser F. Experimental and theoretical investigations on sonoluminescence under dual frequency conditions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2008;15:629–635. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tomita Y., Shima A. Mechanisms of impulsive pressure generation and damage pit formation by bubble collapse. J. Fluid Mech. 1986;169:535. doi: 10.1017/S0022112086000745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kerboua K., Hamdaoui O. Numerical investigation of the effect of dual frequency sonication on stable bubble dynamics. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;49:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kerboua K., Hamdaoui O. Oxidants emergence under dual-frequency sonication within single acoustic bubble: effects of frequency combinations. Iran. J. Chem. Chem. Eng. 2019 doi: 10.30492/ijcce.2019.36705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yasui K., Tuziuti T., Lee J., Kozuka T., Towata A., Iida Y. The range of ambient radius for an active bubble in sonoluminescence and sonochemical reactions. J. Chem. Phys. 2008;128 doi: 10.1063/1.2919119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Calvisi M.L., Lindau O., Blake J.R., Szeri A.J., Blake J.R. Shape stability and violent collapse of microbubbles in acoustic traveling waves Shape stability and violent collapse of microbubbles in acoustic traveling waves. Phys. Fluids. 2011;047101 doi: 10.1063/1.2716633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colussi A.J., Weavers L.K., Hoffmann M.R. Chemical bubble dynamics and quantitative sonochemistry. J. Phys. Chem. A. 1998;102:6927–6934. doi: 10.1021/jp980930t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yasuda K., Torii T., Yasui K., Iida Y., Tuziuti T., Nakamura M., Asakura Y. Enhancement of sonochemical reaction of terephthalate ion by superposition of ultrasonic fields of various frequencies. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2007;14:699–704. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2006.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gogate P.R., Mujumdar S., Pandit A.B. Sonochemical reactors for waste water treatment: comparison using formic acid degradation as a model reaction. Adv. Environ. Res. 2003;7:283–299. doi: 10.1016/S1093-0191(01)00133-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yasui K. Theor. Exp. Sonochemistry Involv. Inorg. Syst. National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology; Anagahora-Japan: 2011. Fundamentals of acoustic cavitation and sonochemistry; pp. 1–29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yasui K., Tuziuti T., Lee J., Kozuka T., Towata A., Iida Y. Numerical simulations of acoustic cavitation noise with the temporal fluctuation in the number of bubbles. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2010;17:460–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2009.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee M., Oh J. Synergistic effect of hydrogen peroxide production and sonochemiluminescence under dual frequency ultrasound irradiation. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2011;18:781–788. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2010.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guédra M., Inserra C., Gilles B., Béra J.C. Numerical investigations of single bubble oscillations generated by a dual frequency excitation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2015;656 doi: 10.1088/1742-6596/656/1/012019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suzuki H., Lee I.Y.S., Okuno Y. Stability and dancing dynamics of acoustic single bubbles in aqueous surfactant solution. Int. J. Phys. Sci. 2010;5:176–181. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasui K. Influence of ultrasonic frequency on multibubble sonoluminescence. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2002;112:1405–1413. doi: 10.1121/1.1502898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toegel R., Lohse D. Phase diagrams for sonoluminescing bubbles: a comparison between experiment and theory. J. Chem. Phys. 2003;118:1863–1875. doi: 10.1063/1.1531610. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hilgenfeldt S., Lohse D., Brenner M.P. Phase diagrams for sonoluminescing bubbles. Phys. Fluids. 1996;8:2808–2826. doi: 10.1063/1.869131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.K. Kerboua, O.H.-I.J. of C. and Chemical, undefined 2019, Oxidants emergence under dual-frequency sonication within single acoustic bubble: effects of frequency combinations, Ijcce.Ac.Ir. (n.d.).

- 37.Kerboua K., Hamdaoui O. Computational study of state equation effect on single acoustic cavitation bubble’s phenomenon. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017;38:174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kerboua K., Hamdaoui O. Ultrasonic waveform upshot on mass variation within single cavitation bubble: investigation of physical and chemical transformations. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;42:508–516. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2017.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kerboua K., Hamdaoui O. Insights into numerical simulation of controlled ultrasonic waveforms driving single cavitation bubble activity. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018;43:237–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2018.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yasui K. Alternative model of single bubble sonoluminescence. Phys. Rev. E. 1997;56:6750–6760. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevA.65.054304. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.