Abstract

Cancers can develop the ability to evade immune recognition and destruction. Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are drugs targeting these immune evasion mechanisms. ICIs have significantly improved outcomes in several cancers including metastatic melanoma. However, data on toxicities associated with allograft transplant recipients receiving ICI is limited. We describe a case of a 71-year-old woman who was diagnosed with metastatic melanoma 13 years after renal transplantation. She was commenced on the ICI nivolumab. She developed acute renal transplant rejection 15 days after administration of the first dose. She continues on haemodialysis but has demonstrated complete oncological response. This case demonstrates the risk of acute renal transplant rejection versus improved oncological outcomes. Patients and clinicians must consider this balance when initiating ICI therapy in allograft transplant recipients. Patients should be fully consented of the potential consequences of acute renal transplant rejection including lifelong dialysis.

Keywords: unwanted effects / adverse reactions, skin cancer, cancer intervention, malignant disease and immunosuppression

Background

Allograft transplant recipients commonly receive immunosuppressive drugs to reduce the risk of transplant rejection. These drugs decrease immunosurveillance and result in activation of oncogenic viruses, contributing to an increased risk of developing cancer.1 Examples of such viruses include the human papillomavirus, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus.2 It is estimated that renal transplant recipients have a three to five times increased risk of developing lung cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancers, particularly squamous cell cancer.3 4

In addition to the original six Hallmarks of Cancer, Hanahan and Weinberg subsequently described the evasion of immune destruction as a further hallmark.5 In a healthy individual, cytotoxic natural killer cells and T cells are responsible for the recognition of, and subsequent immune response against tumour cells.6 However, some cancers develop mutations granting the ability to evade immune recognition and consequent immune-mediated apoptosis.7 Upregulated expression of programmed cell death ligands (PD-L1 and PD-L2) have been observed in several cancers including melanoma.3 These ligands bind to programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptors on T cells and cause T cell inhibition. Similarly, an increased expression of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) on cancer cells can result in the inhibition of T cell function.8 With this protection from the immune system, cancer cells can proliferate unchecked.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) are anti-cancer therapies that target these immune cell recognition pathways. Nivolumab and pembrolizumab are monoclonal antibodies that bind to the PD-1 receptor on T cells, preventing its interaction with PD-L1 and PD-L2 ligands on cancer cells. This inhibits the ability of a cancer cell to evade recognition by host T cells.9 10 Ipilimumab is another monoclonal antibody that blocks CTLA-4 signalling, allowing physiological T cell responses.11

ICIs have revolutionised the treatment of several cancers including metastatic melanoma. Both single agent and combination therapy are effective in this setting, with 5-year survival reported as 52% in the CheckMate 067 study of combination ipilimumab with nivolumab.12

However, the use of ICIs is associated with immune-mediated adverse reactions (IMARs). These adverse reactions can be organ-specific or organ non-specific. Organ-specific toxicity can resemble autoimmune disease and is due to an enhanced activity of the immune system. Examples of such reactions include endocrinopathies, colitis, nephritis and pneumonitis.13–15 The risk and consequences of IMARs are more significant in allograft transplant recipients. The stimulation of immune activity caused by ICIs increases the risk of the transplanted organ being recognised as foreign. This can ultimately lead to transplant rejection. Therefore, care must be taken when considering ICI therapy in allograft transplant recipients.

We present a case from our unit where a renal transplant recipient opted to receive an ICI following a diagnosis of metastatic melanoma.

Case presentation

A 71-year-old woman with renal failure secondary to primary chronic pyelonephritis received a living unrelated donor kidney transplant in 2003. Her immunosuppressant therapy for transplant rejection prevention was mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus and prednisolone at this time.

She then presented with an enlarging non-ulcerating left scalp lesion in 2016. This was subsequently diagnosed as a Breslow thickness 1.6 mm superficial spreading malignant melanoma. She underwent a wide local excision, burring of outer cortex of skull and split skin grafting in the same year. Due to the location of the lesion, the medical team decided not to perform a sentinel lymph node biopsy at this stage.

In October 2017, she was diagnosed with a second melanoma—on this occasion an ulcerating Breslow thickness 2.3 mm lentigo maligna melanoma on her left temple. This was also excised. A staging CT scan at this time showed a nodule of unknown significance in the left lung upper lobe. Another CT scan 4 months later demonstrated two new coalescent nodules in the right lung middle lobe while the left lung upper lobe nodule from the previous scan remained unchanged. Her case was reviewed at the local tumour board and the consensus was that this was likely in keeping with metastatic spread from a melanoma primary. Therefore, she did not have a biopsy of the lung lesions or a PET-CT (positron emission tomography-CT) at this stage and the decision was made to monitor closely with repeat imaging.

In July 2018, the patient developed left neck lymphadenopathy. A new 1.2 cm malignant level V neck node and a new 6 mm left lung lower lobe nodule suspicious for metastasis was noted on repeat CT scan. Her previously noted lung lesions were stable. She underwent a left neck levels II-V nodal dissection. Three of the 55 dissected lymph nodes tested positive for metastatic melanoma which was wild type for BRAF, Kit and NRAS. At this stage, her immunosuppressant therapy consisting of mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus and prednisolone was reduced to tacrolimus (1.5 mg, two times per day) and prednisolone (5 mg, one time per day) in an attempt to slow disease progression.

In November 2018, she then developed four nodules on her scalp. These nodules were completely excised, with two of the nodules showing recurrence of melanoma. BRAF testing was discussed at the local tumour board but it was felt that the recurrence was consistent with the surgical specimen 4 months prior; BRAF re-testing was therefore not re-performed. Systemic treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab for metastatic melanoma was considered at this point. As the patient was clinically well, with a slow rate of disease progression and ICI therapy would potentially have a high risk of renal transplant rejection, the decision was taken to manage conservatively and observe closely after discussion with the patient.

However, by May 2019, the patient had further disease progression with new scalp nodules, an enlarged parotid lymph node and an increased number and size of pulmonary nodules. As the disease was gathering pace, it was agreed to commence ICI therapy in the form of nivolumab, 480 mg every 4 weeks.

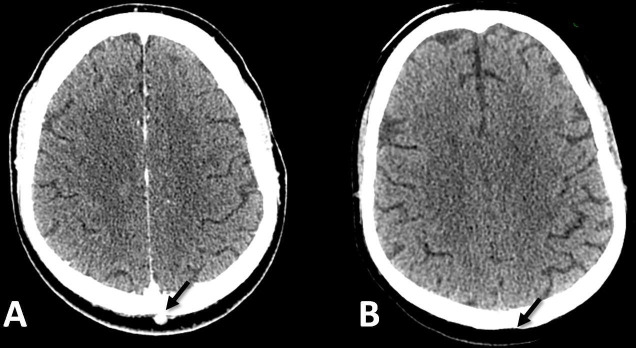

Prior to commencing immunotherapy, her baseline creatinine was 100 umol/L and urea was 7.5 mmol/L. Fifteen days after the first dose of treatment, she developed oliguria, shortness of breath, bilateral pedal oedema and a 3 kg weight gain. Blood tests showed that creatinine had risen to 392 umol/L and urea to 19.2 mmol/L (figure 1), corresponding to acute kidney injury stage 3. The patient was diagnosed with acute renal transplant rejection and commenced on haemodialysis. Her tacrolimus was stopped but she remained on prednisolone to reduce symptoms of transplant rejection.

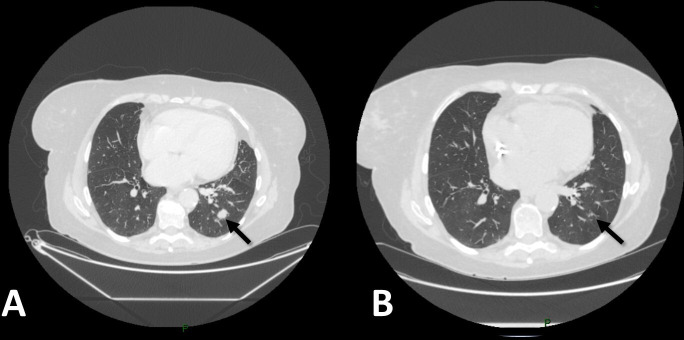

Figure 1.

Changes in creatinine from baseline to post-acute renal transplant rejection.

Outcome and follow-up

The patient continued with her nivolumab regime post-transplant rejection. Imaging after seven cycles of nivolumab therapy showed complete response to therapy with a resolution of the pulmonary nodules (figure 2) and resolution of the two scalp nodules (figures 3 and 4). This response is ongoing. She did not experience any adverse skin effects during her nivolumab treatment. Interruption of her therapy was discussed at length, but the patient expressed her wish to continue receiving her therapy. She will complete a 2-year course of nivolumab in March 2021. She remains on low-dose prednisolone and three-times-a-week haemodialysis.

Figure 2.

CT scan of the lungs before nivolumab (A) and after seven cycles of nivolumab (B). A 15 mm lung nodule in the left lung lower lobe (arrowed) has resolved within this period.

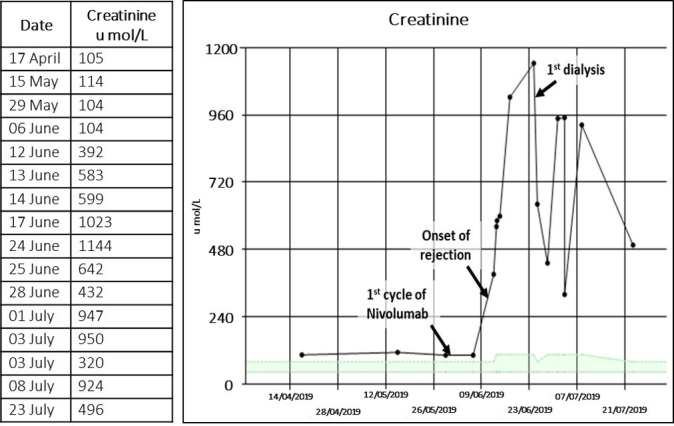

Figure 3.

CT scan of the head before nivolumab (A) and after seven cycles of nivolumab (B). A 22 mm lesion in the left occipital region (arrowed) has resolved with some scarring within this period.

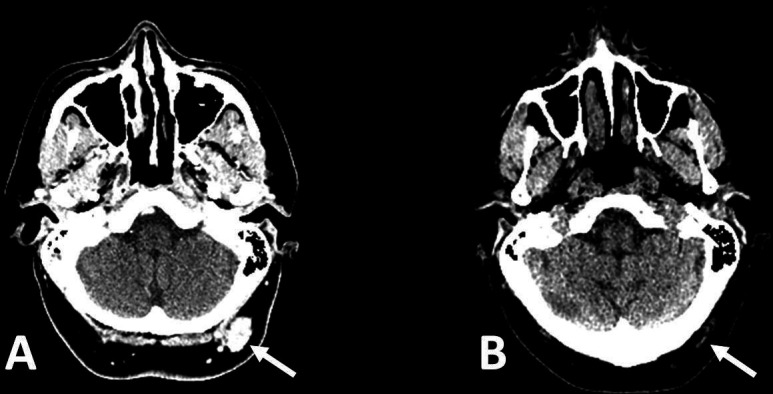

Figure 4.

CT scan of the head before nivolumab (A) and after seven cycles of nivolumab (B). A 6 mm lesion in the posterior midline of the scalp (arrowed) has completely resolved within this period.

Discussion

Before the introduction of ICIs, prognosis for advanced melanoma was poor. Patients treated with dacarbazine and interleukin-2 had a median overall survival (mOS) of 11.2 months and 19.6 months, respectively.16 17 However, trials have proven the higher efficacy of ICIs in the management of melanoma.

The CheckMate 067 trial demonstrated that for patients receiving nivolumab alone for stage III or IV melanoma (with or without BRAF mutations), the overall 5-year survival was 44% and mOS was 36.9 months.12 The same trial also demonstrated that for patients receiving the combination of nivolumab with ipilimumab, the mOS was 60.0 months and the overall 5-year survival was 60% in tumours with BRAF mutation and 48% in tumours without BRAF mutation. The combination arm was associated with significantly higher levels of IMARs. A total of 22% of these patients had complete oncological response, 36% had partial response and 12% had stable disease.12 The KEYNOTE-001 trial demonstrated that pembrolizumab alone in advanced melanoma achieved a mOS of 23.8 months and an overall 5-year survival of 34%. A total of 16% of patients in this trial had complete response, 25% had partial response and 24% had stable disease.18 Studies comparing nivolumab with pembrolizumab have shown a mOS of 23.9 months with nivolumab compared with 22.6 months with pembrolizumab19

The aforementioned trials excluded transplant recipients in their study, and therefore data on toxicities in this patient group is derived primarily from case reports and series.

We describe a case of acute renal transplant rejection requiring dialysis after commencement of nivolumab for metastatic melanoma. The onset of rejection was approximately 15 days post cycle 1, despite ongoing tacrolimus and prednisolone immunosuppression. The patient has subsequently had complete oncological response and continues on her nivolumab therapy. This case adds on to a growing number of cases involving renal transplant recipients receiving ICI therapy for metastatic melanoma. Table 1 compares our case with other previously reported cases.

Table 1.

Case reports of renal transplant recipients receiving ICI therapy for metastatic melanoma

| Case | Immune checkpoint inhibitor | Age | Sex | Kidney disease | Kidney transplantation | Melanoma diagnosis (year diagnosed) |

Site of metastases (year diagnosed) |

Immunosuppression before initiation of ICI | Allograft rejection | Time interval from ICI to rejection | Treatment duration | Treatment response |

| This case | Nivolumab alone | 71 | F | Chronic primary pyelonephritis | 2003 | 1.6 mm superficial spreading melanoma (2016) | Lung and scalp | Tacrolimus and prednisolone | Acute T cell mediated rejection | 15 days | Ongoing | Complete response |

| Ong et al26 | 63 | F | Hypertension and diabetes mellitus | 2004 | 2.59 mm melanoma | Lung and hilar lymph nodes | Prednisolone | Acute T cell mediated rejection | 8 days | Ongoing | Partial response | |

| Winkler et al27 | 60 | F | Polycystic kidney disease | 2003 | Metastatic melanoma (2014) | Lung, brain and intrathoracic lymph nodes (2016) | Prednisolone and mycophenolate mofetil | No rejection | NIL | Four doses | Disease progression | |

| Tio et al28 | 48 | M | NR | NR | Metastatic melanoma | NR | Tacrolimus and prednisolone | Acute T cell mediated rejection | NR | One dose | Partial response | |

| Deltombe et al29 | 73 | M | NR | NR | Superficial spreading melanoma | NR | Everolimus | Acute T cell mediated rejection | 85 days | Two doses | Disease progression | |

| Winkler et al27 | Pembrolizumab alone | 58 | M | Hydronephrosis | 1982 | Uveal melanoma (2013) | Lung, liver and bone (2015) | Cyclosporine | No rejection | NIL | Four doses | Disease progression |

| Kwatra et al30 | 58 | M | IgM nephropathy | 2001 | 21 mm ulcerated nodular melanoma | Liver, bone, hilar lymph nodes and porta hepatis lymph nodes | Azathioprine and everolimus | Rejection | 42 days | Two doses | Disease progression | |

| Tio et al28 | 70 | M | NR | NR | Metastatic melanoma | NR | Tacrolimus and prednisolone | No rejection | NIL | NR | Disease progression | |

| Tio et al28 | 75 | M | NR | NR | Metastatic melanoma | NR | Prednisolone | No rejection | NIL | NR | Partial response | |

| Tio et al28 | 65 | M | NR | NR | Metastatic melanoma | NR | Prednisolone, mycophenolate mofetil, tacrolimus | No rejection | NIL | NR | Disease progression | |

| Winkler et al27 | 58 | M | Hydronephrosis | 1982 | Uveal melanoma (2013) | Lung, liver and bone (2015) | Cyclosporine | No rejection | NIL | Four doses | Disease progression | |

| Lipson et al31 | Ipilimumab alone | 72 | M | Hypertension | 2000 | 8 mm ulcerated melanoma (2008) | Left axillary lymph nodes | Prednisolone | No rejection | NIL | NR | Complete response |

| Lipson et al31 | 58 | M | Polycystic kidney disease | 2004 | 4.2 mm nodular melanoma (2011) | Lung, right neck lymph nodes and mesenteric lymph nodes | Prednisolone | No rejection | NIL | Four doses | Disease progression | |

| Jose et al32 | 40 | M | NR | 1997 | Ocular melanoma (2013) | Liver (2013) | Prednisolone | Acute T cell mediated rejection | NR | Two doses | Disease progression | |

| Zehou et al33 | 67 | M | Nephroangiosclerosis and diabetes mellitus | 2012 | Metastatic melanoma (2014) | Lymph nodes | Everolimus | No rejection | NIL | Four doses | Disease progression | |

| Zehou et al33 | 57 | F | Polycystic kidney disease | 2007 | Lentigo malignant melanoma (2010) | Lymph nodes | Sirolimus and prednisolone | No rejection | NIL | NR | Disease progression | |

| Zehou et al33 | 68 | F | Polycystic kidney disease | 2001 | Metastatic melanoma | Lung, liver, bone and lymph nodes | Everolimus and prednisolone | No rejection | NIL | Two doses | Disease progression |

ICI, immune checkpoint inhibitor; NR, not reported.

A study by Manohar et al showed that 8/18 (44.4%) renal transplant recipients treated with nivolumab alone experienced rejection. This was compared with 3/18 (16.6%) patients who were treated with pembrolizumab alone and 2/18 (11.1%) with ipilimumab alone. Median time from ICI initiation to acute renal transplant rejection in this study was 24 days. Of these 18 patients whom developed acute renal transplant rejection after ICI therapy, 9 (50.0%) patients had favourable response (stable disease, partial response and complete response) while 7 (38.9%) patients had progressive disease. This is compared with patients whom did not develop acute renal transplant rejection after ICI therapy where 11/25 (44.0%) had favourable response and 14/25 (56.0%) had progressive disease.20 The connection between oncological response and incidence of IMARs as shown by this study has similarly been demonstrated by Indini A et al. This study correlated the incidence of IMARs with improved progression-free survival. Median overall survival for patients who experienced IMARs was 21.9 months, as compared with 9.7 months in patients who did not experience IMARs.21

Fisher et al reported that 7/11 (64%) patients experienced acute renal transplant rejection when treated with nivolumab alone; 2/8 (25%) acute renal transplant recipients treated with pembrolizumab and another 2/8 (25%) treated with ipilimumab alone also had acute renal transplant rejection.22

Another study by Smedman et al showed that 4/7 (57.1%) renal transplant recipients treated with PD-1 inhibitor alone had acute transplant rejection. This was the same for 1/3 (33.3%) renal transplant recipients treated with ipilimumab alone.23

Abdel-Wahab et al demonstrated that 2/5 (40.0%), 4/9 (44.4%) and 2/4 (50.0%) renal transplant recipients had acute transplant rejection when treated with nivolumab, pembrolizumab and ipilimumab alone, respectively.21 The median time from ICI initiation to acute renal transplant rejection were 18.5 days for nivolumab alone, 21 days for pembrolizumab alone and 21 days for ipilimumab alone.24

Our patient’s experience follows closely with the results of the above studies. The higher incidence of acute transplant rejection associated with nivolumab demonstrated by the studies corresponds with the acute transplant rejection in our patient after nivolumab initiation. Our patient also had complete oncological response, tallying with the higher percentage of patients having both IMARs and favourable oncological response. Our patient developed acute transplant rejection 15 days after ICI initiation, similar to the 18.5 days demonstrated by Abdel-Wahab et al.

Since the decision to continue treatment was made, new evidence has been published showing the efficacy of interrupting treatment early in patients achieving complete oncological response. The KeyNote-006 trial demonstrated that patients who achieved complete oncological response and received 2 years of pembrolizumab treatment had an estimated 24-month progression-free survival (PFS) of 85.4%. In those who achieved complete oncological response but received less than 2 years of pembrolizumab (6 months of pembrolizumab and two additional doses after first scan showing complete response) PFS was 86.4%.25 This highlights the durability of response in patients who have a complete oncological response and provides reassurance to clinicians and patients about treatment interruption if required.

In summary, patients with organ transplants appear to have a high chance of organ rejection with use of ICI, but this comes with a greater chance of oncological response. This case and the other published reports highlight the importance of an individualised discussion with each patient, enabling an informed treatment decision to be made.

Patient’s perspective.

Q: How was your journey from the very beginning, from the melanoma diagnosis?

A: I wasn’t frightened at the initial diagnosis of the melanoma; it was very quickly cut out from the top of my scalp. I was only really worried when it spread to my lymph nodes, worried that it might have spread elsewhere. It was also scary when my neck blew up after the operation and when I went to the intensive care unit. I was a bit more assured when the doctors told me that only 3 out of 55 of the lymph nodes were infected. I was initially told that I had 3 to 6 months to live if I didn’t go for the immunotherapy. I still wanted to be around with kids and it felt like there was no choice but to go for the immunotherapy.

There was some trauma with the rejection, but I was aware and open to dialysis. I felt that it was an acceptable risk compared with only having 3 to 6 months to live. There is some regret about the rejection with how I’m living my life now, mainly because of the breathlessness. I can’t walk short distances anymore without feeling breathless and needing to sit down. It’s definitely lowered my quality of life a bit, but I am very thankful for my husband for helping me around. Just last week I had around 1.5 L of fluid drained from my lungs. This was after the doctors were trying to drain fluid everywhere else that was not there. I felt much better after taking off the fluid, but I feel that it’s coming back again.

I am not someone who thinks too much of the future, I prefer to take it 1 hour at a time and live in the now, but there is definitely some anxiety of the unknown.

My brother died of neck cancer, back when there was no immunotherapy. I thought that it was really scary and I didn’t want to go through it without trying the immunotherapy. I see immunotherapy as hope.

Q: Would you ‘recommend’ immunotherapy to people like you?

A: Yes, I would ‘recommend’ it. The diarrhoea I had was problematic but bearable in the end. I think I was very lucky with the side effects in the way that it’s not as bad as some people.

Q: How would you describe your journey?

A: Definitely rocky with its up and downs.

Q: If you were to go back to 2016, back to the beginning, would you have done anything differently? Would you have asked for anything differently?

A: Not at all. I am very happy with the care I have been provided, the staff and my entire journey. I’ve got no complains whatsoever. And no, I don’t think I would have done anything differently. I feel very supported.

Q: Do you feel that the rejection was worth it?

A: Yes, it was worth the rejection. I am ok with the dialysis three times a week; I am managing well with this.

Q: What went through your mind during the period of rejection?

A: I thought it was over and I actually wished it was over; I wasn’t sure I was able to cope with it anymore, with one thing coming after another.

Q: What are your prospects for the future from today onwards?

A: I’m hoping to continue to get away on weekends, go for walks once in a while. I am very lucky to have my husband who pushes me, encourages me, and who is a good support. I want to continue getting hugs from my grandchildren. Life is too short to give up. I have a tremendous amount of support too from my faith. It may be silly to some people the amount of support I get from my faith, but it is very important to me.

Learning points.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) therapy has greatly improved metastatic melanoma outcomes.

Renal transplant recipients risk acute renal transplant rejection when receiving ICI therapy.

Clinicians must consider the risk of acute renal transplant rejection alongside the benefit of improved oncological outcomes with ICI.

Patients should be fully consented of the potential consequences of acute renal transplant rejection including lifelong dialysis before deciding to initiate ICI therapy.

Acknowledgments

Dr Mark Baxter is a Clinical Academic Fellow funded by the Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office.

Footnotes

Contributors: Dr Brandon Tan collected data on the patient, wrote this case report and obtained consent from the patient. Dr Mark Baxter supervised the writing of this case report and critically reviewed the accuracy of information presented in this case report. Dr Richard Casasola provided advice and support for the writing of this case report and was the Oncologist responsible for the patient’s care. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Acuna SA Etiology of increased cancer incidence after solid organ transplantation. Transplant Rev 2018;32:218–24. 10.1016/j.trre.2018.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo GG, Ou J-hsiungJ. Oncogenic viruses and cancer. Virol Sin 2015;30:83–4. 10.1007/s12250-015-3599-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lai H-C, Lin J-F, Hwang TIS, et al. Programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) inhibitors in renal transplant patients with advanced cancer: a double-edged sword? Int J Mol Sci 2019;20:2194. 10.3390/ijms20092194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sprangers B, Nair V, Launay-Vacher V, et al. Risk factors associated with post-kidney transplant malignancies: an article from the Cancer-Kidney international network. Clin Kidney J 2018;11:315–29. 10.1093/ckj/sfx122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 2011;144:646–74. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonzalez H, Hagerling C, Werb Z. Roles of the immune system in cancer: from tumor initiation to metastatic progression. Genes Dev 2018;32:1267–84. 10.1101/gad.314617.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez PC, Zea AH, Ochoa AC. Mechanisms of tumor evasion from the immune response. Cancer Chemother Biol Response Modif 2003;21:351–64. 10.1016/s0921-4410(03)21018-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seidel JA, Otsuka A, Kabashima K. Anti-Pd-1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapies in cancer: mechanisms of action, efficacy, and limitations. Front Oncol 2018;8:86. 10.3389/fonc.2018.00086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo L, Zhang H, Chen B. Nivolumab as programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor for targeted immunotherapy in tumor. J Cancer 2017;8:410–6. 10.7150/jca.17144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McDermott J, Jimeno A. Pembrolizumab: PD-1 inhibition as a therapeutic strategy in cancer. Drugs Today 2015;51:7–20. 10.1358/dot.2015.51.1.2250387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tarhini A, Lo E, Minor DR. Releasing the brake on the immune system: ipilimumab in melanoma and other tumors. Cancer Biother Radiopharm 2010;25:601–13. 10.1089/cbr.2010.0865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Five-Year survival with combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med 2019;381:1535–46. 10.1056/NEJMoa1910836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olsson-Brown AC, Baxter M, Dobeson C, et al. Real-World outcomes of immune-related adverse events in 2,125 patients managed with immunotherapy: a United Kingdom multicenter series. JCO 2020;38:7065 10.1200/JCO.2020.38.15_suppl.7065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daniels GA, Guerera AD, Katz D. Challenge of immune-mediated adverse reactions in the emergency department '. Emerg Med J 2018;1:369–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Nivolumab, 2020. Available: https://bnf.nice.org.uk/drug/nivolumab.html [Accessed 20 May 2020].

- 16.Ascierto PA, Long GV, Robert C, et al. Survival outcomes in patients with previously untreated BRAF wild-type advanced melanoma treated with nivolumab therapy: three-year follow-up of a randomized phase 3 trial. JAMA Oncol 2019;5:187–94. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.4514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alva A, Daniels GA, Wong MKK. Contemporary experience with high-dose interleukin-2 therapy and impact on survival in patients with metastatic melanoma and metastatic renal cell carcinoma', cancer immunology. Immunotherapy 2016;65:1533–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Five-Year survival outcomes for patients with advanced melanoma treated with pembrolizumab in KEYNOTE-001. Ann Oncol 2019;30:582–8. 10.1093/annonc/mdz011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moser JC, Wei G, Colonna SV, et al. Comparative-Effectiveness of pembrolizumab vs. nivolumab for patients with metastatic melanoma. Acta Oncol 2020;59:434–7. 10.1080/0284186X.2020.1712473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manohar S, Thongprayoon C, Cheungpasitporn W, et al. Systematic review of the safety of immune checkpoint inhibitors among kidney transplant patients. Kidney Int Rep 2020;5:149–58. 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Indini A, Di Guardo L, Cimminiello C, et al. Immune-Related adverse events correlate with improved survival in patients undergoing anti-PD1 immunotherapy for metastatic melanoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2019;145:511–21. 10.1007/s00432-018-2819-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher J, Zeitouni N, Fan W, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in solid organ transplant recipients: a patient-centered systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol 2020;82:1490–500. 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smedman TM, Line P-D, Guren TK, et al. Graft rejection after immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy in solid organ transplant recipients. Acta Oncol 2018;57:1414–8. 10.1080/0284186X.2018.1479069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abdel-Wahab N, Safa H, Abudayyeh A, et al. Checkpoint inhibitor therapy for cancer in solid organ transplantation recipients: an institutional experience and a systematic review of the literature. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:106. 10.1186/s40425-019-0585-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robert C, Ribas A, Schachter J, et al. Pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma (KEYNOTE-006): post-hoc 5-year results from an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol 2019;20:1239–51. 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30388-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ong M, Ibrahim AM, Bourassa-Blanchette S, et al. Antitumor activity of nivolumab on hemodialysis after renal allograft rejection. J Immunother Cancer 2016;4:64. 10.1186/s40425-016-0171-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Winkler JK, Gutzmer R, Bender C, et al. Safe administration of an anti-PD-1 antibody to kidney-transplant patients: 2 clinical cases and review of the literature. J Immunother 2017;40:341–4. 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tio M, Rai R, Ezeoke OM, et al. Anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immunotherapy in patients with solid organ transplant, HIV or hepatitis B/C infection. Eur J Cancer 2018;104:137–44. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.09.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deltombe C, Garandeau C, Renaudin K, et al. Severe allograft rejection and autoimmune hemolytic anemia after anti-PD1 therapy in a kidney transplanted patient. Transplantation 2017;101:297 10.1097/TP.0000000000001861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kwatra V, Karanth NV, Priyadarshana K, et al. Pembrolizumab for metastatic melanoma in a renal allograft recipient with subsequent graft rejection and treatment response failure: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2017;11:73. 10.1186/s13256-017-1229-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipson EJ, Bodell MA, Kraus ES, et al. Successful administration of ipilimumab to two kidney transplantation patients with metastatic melanoma. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:e69–71. 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.2314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jose A, Yiannoullou P, Bhutani S, et al. Renal allograft failure after ipilimumab therapy for metastatic melanoma: a case report and review of the literature. Transplant Proc 2016;48:3137–41. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zehou O, Leibler C, Arnault J-P, et al. Ipilimumab for the treatment of advanced melanoma in six kidney transplant patients. Am J Transplant 2018;18:3065–71. 10.1111/ajt.15071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]