Abstract

Objectives:

This study examines receipt of formal sex education as a potential mechanism that may explain the observed associations between disability status and contraceptive use among young women with disabilities.

Study Design:

Using the 2011–17 National Survey of Family Growth, we analyzed data from 2,861 women aged 18 to 24 years, who experienced voluntary first sexual intercourse with a male partner. Women whose first intercourse was involuntary (7% of all women reporting sexual intercourse) were excluded from the analytic sample. Mediation analysis was used to estimate the indirect effect of receipt of formal sex education before first sexual intercourse on the association between disability status and contraceptive use at first intercourse.

Results:

Compared to nondisabled women, women with cognitive disabilities were less likely to report receipt of instruction in each of six discrete formal sex education topics and received instruction on a fewer number of topics overall (B = −0.286, 95% CI = −0.426 to −0.147), prior to first voluntary intercourse. In turn, the greater number of topics received predicted an increased likelihood of contraceptive use at first voluntary intercourse among these women (B = 0.188, 95% CI = 0.055 to 0.321). No significant association between non-cognitive disabilities and receipt of formal sex education or contraceptive use at first intercourse was observed.

Conclusions:

Given the positive association between formal sex education and contraceptive use among young adult women with and without disabilities, ongoing efforts to increase access to formal sex education are needed. Special attention is needed for those women with cognitive disabilities.

Keywords: cognitive disability, non-cognitive disability, contraception, formal sex education

1. Introduction

Despite persistent misconceptions, women with disabilities are sexually active throughout life [1, 2]. During adolescence and young adulthood, women with moderate or mild disabilities are as likely to report having sexual intercourse as their nondisabled peers and report similar (or earlier) age at first intercourse [3–6]. At the same time, women with disabilities are more likely to engage in sexual risk behaviors, especially contraceptive nonuse, compared to nondisabled women. Adolescent and young adult women with disabilities report lower rates of contraceptive use and higher rates of unintended pregnancy than their peers without disabilities [3, 7–10]. Further, reproductive-aged women with physical or cognitive disabilities are less likely to use either highly effective long-acting reversible contraception (i.e., intrauterine device [IUD] or implant) or moderately effective hormonal methods (e.g., pill, patch) than nondisabled women [11, 12], and those with cognitive disabilities are also less likely to use any contraception [11, 13].

A key strategy for promoting sexual and reproductive health in young women, including contraceptive use, is formal sex education provided by schools or community organizations [14, 15]. Notwithstanding an increased risk of sexual risk behavior among young women with disabilities [7–9], many are likely to experience barriers in accessing formal sex education, especially those with intellectual disabilities or those in special education [4, 16]. To our knowledge, no previous research examined differences in receipt of formal sex education between young women with and without disabilities using population-based data. Less is known about the role of formal sex education on contraceptive use among young women with disabilities.

We used a nationally representative sample from the 2011–17 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) to examine the role of formal sex education in contraceptive use for young women with disabilities. We hypothesized that women with disabilities would be less likely to receive formal sex education before first intercourse than their nondisabled peers, which in turn, would be associated with a lower likelihood of contraceptive use at first intercourse. We focused on first intercourse because of its central role in shaping young women’s developmental trajectories and subsequent sexual experiences [17], and allowed control of relevant contextual factors, such as the nature of the relationship with the first sexual partner (e.g., married partner, stranger) [6, 18, 19]. Given research suggesting the varying significance of sex education topics (i.e., abstinence-only or more comprehensive education) on contraceptive use [14, 20], we assessed the individual association of contraceptive use with each of six discrete education topics surveyed by the NSFG separately, as well as the total number of topics received.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Data and sample

We used data from the 2011–17 NSFG, a cross-sectional household survey of women (and men) ages 15–44 years, including those living in non-institutional group settings (e.g., college dormitories, sororities) [21]. Individuals who reside in institutionalized settings are not included. The NSFG provides nationally representative estimates of sexual activity, pregnancy, and contraceptive use. Detailed methodology for the NSFG has been reported elsewhere [22]. We combined data from 2011–13, 2013–15, and 2015–17, resulting in a data file of 16,854 female respondents.

We analyzed data from women ages 18–24 years (n = 3,884) who experienced their first intercourse with a male (n = 3,136). Respondents in only this age range were asked both about their first sexual experience and receipt of formal sex education, and thus were eligible for inclusion in the sample. Of 748 female respondents ages 18–24 years who were excluded from the analytic sample because they did not report sexual intercourse with a male, 73 (9%, weighted) had sexual experiences with a female partner, and 180 (26%) had non-vaginal sexual intercourse with a male partner while the remaining respondents reported no sexual experience. Further excluded were women who reported their first intercourse was involuntary (n = 242) in consideration of the higher risk of sexual assault among women with cognitive disabilities than their nondisabled counterparts [23,24] and the potential compounding associations between the involuntary nature of first intercourse, formal sex education, and contraceptive use [25]. Thirty-three additional respondents were excluded due to missing disability or involuntary sex status, resulting in the final sample of 2,861 women.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Disability

Disability status was ascertained through a standard set of six questions developed by the U.S. Census Bureau [26]. The questions ask whether respondents had serious difficulty in: hearing; seeing, even if glasses are utilized; concentrating, remembering or making decisions; walking or using stairs; dressing or bathing; and doing errands without assistance. Given prior research showing differences in sexual health outcomes by type of disabilities [1, 3], we created three mutually-exclusive groups [14, 27]: (1) no disability (n = 2,248; 80%, weighted); (2) cognitive disability (n = 423; 14%), which included women who reported difficulty remembering or making decisions regardless of the presence of other types of disabilities; and (3) non-cognitive disability only (n = 190; 6%), which included women who reported difficulties other than remembering or making decisions. In our preliminary analysis, we used four disability groups (i.e., no disability, cognitive only, non-cognitive only, both types of disabilities) in accordance with other prior studies [13]. Women with cognitive disabilities only (n = 271) and those with both disabilities (n = 152) showed similar patterns of association between receipt of formal sex education and contraceptive use, although the indirect effects of receiving formal sex education were greater among women with both types of disabilities (full results are available from authors upon request).

2.2.2. Contraceptive use at first sex

Respondents were asked whether they used contraception at first intercourse, and, if so, the type of method used. Consistent with previous studies [11, 28], we created a categorical variable indicating the use of reversible contraceptive methods that are highly (i.e., IUD, implant) or moderately (e.g., injectable, pill) effective at preventing pregnancy; less effective (e.g., male condom, withdrawal, rhythm method); and no method. Due to the small number of the sampled women with non-cognitive disabilities who used a highly or moderately effective method (n = 18), we used a binary indicator of contraceptive use versus nonuse for multivariable analyses.

2.2.3. Formal sex education

To ascertain exposure to formal sex education before first intercourse, we used questions about whether respondents reported receipt of any sexuality instruction before age 18 years at school, church, a community center, or some other place, and, if so, what grade (age) they were in when they first received instruction. Instructional topics included: (1) how to say no to sex; (2) methods of birth control; (3) where to get birth control; (4) how to use a condom; (5) sexually transmitted infections (STIs); and (6) preventing HIV/AIDS. We created six dichotomous indicators for each instructional topic and a summary score for the total number of topics received, consistent with other analyses [20].

2.2.4. Covariates

We included individual and family characteristics that are associated with formal sex education and contraceptive use [5, 13, 18, 20]: age, poverty status, race/ethnicity, place of birth, place of residence, religious service attendance at age 14, family religion, living arrangement up to age 14, and the number of sex education topics received from parents or guardians. We further included two contextual variables related to first sex [18, 19]: respondents’ age at first intercourse and relationship status with their partner at the time of first intercourse.

2.3. Analysis

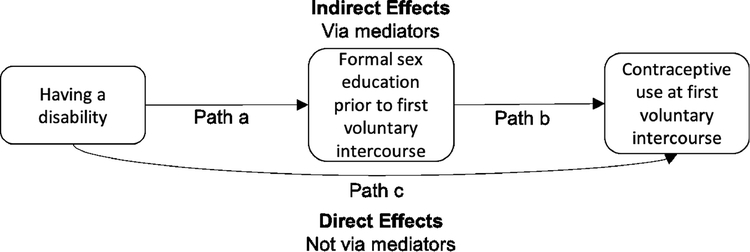

For bivariate analyses, we compared all measures by disability subgroup. Differences between the three disability groups for continuous and categorical variables were tested for significance by survey-weighted linear regression (F-test) and Chi-squared tests, respectively. Next, we estimated logistic regression models to identify the associations of disability and reported receipt of formal sex education with any contraceptive use controlling for covariates. We then conducted mediation analyses to examine whether the association between disability and contraceptive use at first voluntary intercourse was mediated by reported receipt of formal sex education before first voluntary intercourse (see Figure 1 for the hypothesized model). We conducted separate mediation analyses for the two groups of disabled women compared to nondisabled women. We included each of the six formal sex education topics and the summary score separately in the models. The potential for indirect effects was identified using the Stata command medeff, which allows binary mediating and dependent variables [29, 30]. It estimates two separate regression models, one for the mediator variable (i.e., sex education) and the other for the outcome (i.e., contraceptive use), runs simulations from their sampling distribution, and estimates the average direct and indirect effects of the main independent variable (i.e., disability). Finally, as a sensitivity analysis, the above-mentioned bivariate and multivariate models were estimated among all 18 to 24-year-old women regardless of the voluntary nature of their first sexual intercourse. All analyses were conducted in Stata15 and weighted to adjust for the complex survey design of the NSFG. This study used publicly available data and was deemed exempt from human subject review.

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive data

3.1.1. Individual and family characteristics

Respondents were 21.3 years old, on average. About half were non-Hispanic White, 23% were Hispanic, 15% were non-Hispanic Black, and 9% were from other racial/ethnic backgrounds. As shown in Table 1, women with cognitive disabilities were younger than nondisabled women. Women with non-cognitive disabilities were more likely to live in suburban areas than women with cognitive disabilities and nondisabled women. Compared to women without disabilities, those with both types of disabilities were less likely to grow up with both parents. Women with cognitive disabilities also experienced first intercourse at earlier ages and were less likely to have first intercourse with a steady, romantic partner.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics, Receipt of Formal Sex Education, and Contraceptive Use at First intercourse by Disability Status, National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) 2011–2017

| No disability |

Cognitive disability |

Non-cognitive disability |

Group comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %, mean [95% CI] | %, mean [95% CI] | %, mean [95% CI] | ||

| Individual Characteristics | ||||

| Age | 21.4 [21.3, 21.5] | 20.9 [20.6, 21.2] | 21.3 [21.0, 21.7] | p<.01 |

| Federal poverty level | p=.122 | |||

| <100% | 31.0 [28.1, 34.0] | 38.4 [31.4, 45.9] | 39.9 [28.9, 52.0] | |

| 100–199% | 22.9 [20.6, 25.4] | 22.6 [17.8, 28.2] | 21.2 [14.8, 29.3] | |

| 200% or greater | 46.1 [42.9, 49.4] | 39.0 [31.6, 46.9] | 39.0 [28.9, 50.1] | |

| Race/ethnicity | p=.228 | |||

| Non-Hispanic white | 52.9 [48.7, 57.0] | 57.6 [50.7, 64.2] | 49.0 [36.7, 61.5] | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 15.6 [13.3, 18.2] | 12.0 [8.8, 16.1] | 17.6 [10.6, 27.8] | |

| Hispanic | 23.0 [19.5, 27.0] | 19.4 [14.3, 25.8] | 28.2 [19.8, 38.5] | |

| Others | 8.5 [6.5, 11.0] | 10.9 [6.5, 17.9] | 5.1 [2.5, 10.0] | |

| Place of birth (1 = foreign-born) | 9.1 [7.4, 11.1] | 6.8 [4.0, 11.3] | 11.1 [5.7, 20.6] | p=.439 |

| Place of residence | p<.01 | |||

| Principal city of MSA | 40.0 [35.1, 45.2] | 32.5 [26.0, 39.8] | 39.3 [28.9, 50.7] | |

| Other MSA | 44.4 [39.2, 49.7] | 47.3 [39.8, 55.0] | 29.1 [21.0, 38.9] | |

| Not MSA | 15.6 [11.9, 20.1] | 20.1 [14.2, 27.7] | 31.6 [18.6, 48.3] | |

| Religious attendance | p=.251 | |||

| Weekly or more often | 48.5 [44.8, 52.2] | 51.0 [44.0, 58.0] | 52.3 [41.7, 62.7] | |

| Sometimes | 33.2 [29.6, 37.0] | 26.2 [20.9, 32.3] | 27.5 [19.9, 36.6] | |

| Never | 18.4 [15.8, 21.2] | 22.7 [17.0, 29.7] | 20.3 [13.8, 28.7] | |

| Context of family of origin | ||||

| Religion raised in | p=.751 | |||

| No religion | 11.9 [10.1, 14.0] | 14.1 [9.7, 19.9] | 14.5 [8.8, 23.0] | |

| Catholic | 33.0 [29.8, 36.3] | 28.2 [22.4, 34.7] | 31.5 [22.2, 42.5] | |

| Protestant | 47.0 [43.3, 50.8] | 47.5 [40.5, 54.6] | 46.4 [35.6, 57.6] | |

| Other | 8.1 [6.1, 10.8] | 10.3 [6.1, 16.8] | 7.6 [3.9, 14.1] | |

| Living arrangement (1 = always lived with both parents) | 54.3 [51.4, 57.2] | 39.8 [32.8, 47.2] | 39.4 [28.9, 51.0] | p<.001 |

| Parental sex education, number of topics received (range = 0–6) | 3.0 [2.8, 3.2] | 2.9 [2.6, 3.2] | 2.9 [2.3, 3.4] | p=.745 |

| First sex context | ||||

| Age at first intercourse | 16.7 [16.5, 16.8] | 16.1 [15.8, 16.4] | 16.2 [15.8, 16.6] | p<.001 |

| Relationship with partner | p<.01 | |||

| Married/engaged/living together | 6.4 [4.8, 8.6] | 4.2 [2.1, 8.0] | 5.9 [3.2, 10.5] | |

| Going steady | 73.5 [70.8, 76.0] | 64.0 [56.9, 70.5] | 75.2 [65.7, 82.8] | |

| Going unsteady/just friend | 16.7 [14.7, 19.0] | 25.5 [20.1, 31.7] | 16.6 [10.5, 25.1] | |

| Other relationship | 3.3 [2.5, 4.5] | 6.4 [4.2, 9.7] | 2.3 [1.0, 5.3] | |

| Receipt of formal sex education | ||||

| How to say no to sex (1= yes) | 79.2 [76.4, 81.8] | 65.8 [58.4, 72.5] | 68.7 [56.6, 78.6] | p<.001 |

| Birth control method (1= yes) | 69.8 [66.9, 72.7] | 58.3 [51.1, 65.2] | 63.5 [53.2, 72.7] | p<.01 |

| Where to get birth control (1= yes) | 56.3 [53.1, 59.5] | 43.8 [36.6, 51.3] | 54.5 [43.9, 64.7] | p<.01 |

| How to use condom (1= yes) | 61.2 [57.8, 64.4] | 45.9 [38.6, 53.4] | 61.3 [52.0, 69.9] | p<.001 |

| STI (1= yes) | 85.6 [83.5, 87.4] | 73.5 [66.5, 79.5] | 80.3 [69.2, 88.1] | p<.001 |

| HIV/AIDS (1= yes) | 81.1 [78.5, 83.4] | 67.8 [60.8, 74.1] | 73.2 [62.3, 81.8] | p<.001 |

| Number of education topics received (range = 0–6) | 4.3 [4.2, 4.5] | 3.5 [3.2, 3.9] | 4.0 [3.7, 4.3] | p<.001 |

| Contraceptive use at first sexual intercourse | ||||

| Highly/moderately effective | 9.9 [8.3, 11.8] | 11.1 [7.1, 16.8] | 9.5 [4.8, 18.1] | p=.176 |

| Less effective | 69.7 [66.4, 72.8] | 62.0 [54.9, 68.7] | 62.7 [51.6, 72.6] | |

| No method | 20.5 [18.0, 23.2] | 26.9 [21.3, 33.3] | 27.9 [19.0, 38.9] | |

| Unweighted n (weighted %) | 2,248 (79.7) | 423 (14.5) | 190 (5.8) | |

CI = confidence interval; MSA = Metropolitan Statistical Area; STI = sexually transmitted infections

Note. Weighted estimates of means or proportions (%) are presented.

3.1.2. Formal sex education

Compared to nondisabled women, those with cognitive disabilities were less likely to report receipt of each of six educational topics and reported receipt of instruction on a fewer number of topics. Women with non-cognitive disabilities reported lower rates of receiving instruction on birth control methods than nondisabled women.

3.1.3. Contraceptive use

Proportions of women who reported using highly/moderately effective methods or less effective methods during their first voluntary sexual intercourse were not significantly different across three groups of women by disability status.

3.2. Regression analysis

We examined associations between disability status, formal sex education, and contraceptive use using stepwise models: Model 1 estimated the association between disability and contraceptive use without any covariates, Model 2 adjusted for individual, family, and first sex contextual variables, and Model 3 also added formal sex education measures (see Table 2). In the unadjusted model (Model 1), women with cognitive disabilities showed lower odds of using contraception at first voluntary intercourse than women without disabilities (Odds Ratio [OR] = 0.70, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] = 0.50 to 0.98). This difference became statistically non-significant after adjusting for covariates in Model 2 (adjusted OR = 0.75, 95% CI = 0.52 to 1.08). Being white, living beyond the 200% federal poverty level, older age at first intercourse, and receiving a broader range of sex educational topics from a parent significantly predicted contraceptive use (not shown in Table 2). No statistically significant difference was found between women with non-cognitive disabilities and nondisabled women before and after adjusting for covariates (aOR = 0.85, 95% CI = 0.51 to 1.42). Among the six discrete sex education topics, reported receipt of instruction on birth control methods (aOR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.08 to 1.94) and STIs (aOR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.02 to 2.02) and a greater number of sex education topics (OR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.01 to 1.15) were associated with an increased likelihood of contraceptive use.

Table 2.

Associations between Disability Status and Receipt of Formal Sex Education on Contraceptive Use, National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) 2011–2017

| Model 1 (No adjustment) | Model 2 (Adjusted for covariates) | Model 3 (Adjusted for covariates and each of formal sex education variables) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| OR [95% CI] | aOR [95% CI] | aOR [95% CI] | |

| Disability status a | |||

| Cognitive disability | 0.70 [0.50, 0.98] | 0.75 [0.52, 1.08] | 0.78 [0.55, 1.11] |

| Non-cognitive disability | 0.67 [0.39, 1.15] | 0.85 [0.51, 1.42] | 0.85 [0.51, 1.43] |

| Receipt of sex education | |||

| Number of topics received | 1.08 [1.01, 1.15] | ||

| How to say no to sex b | 1.10 [0.82, 1.45] | ||

| Birth control method b | 1.45 [1.08, 1.94] | ||

| Where to get birth control b | 1.34 [1.00, 1.81] | ||

| How to use condom b | 1.15 [0.90, 1.48] | ||

| STI b | 1.43 [1.02, 2.02] | ||

| HIV/AIDS b | 1.31 [0.98, 1.75] | ||

(a)OR = (adjusted) odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; STI = sexually transmitted infections

Note. Models 2 and 3 are adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, poverty status, place of birth, residence area, living arrangement up to age 14, family religion, religious service attendance at age 14, sex education received from a parent, age at first intercourse and the nature of relationships with the first sexual partner. Reference categories are no disability a and not receiving each instruction b. Each of the formal sex education topics was added in a separate model. Disability status odds ratio and 95% CI in Model 3 come from the model with the number of sex education topics received.

3.3. Mediation analysis

3.3.1. Women with cognitive disabilities

As shown in Table 3, compared to nondisabled women, women with cognitive disabilities reported receipt of instruction on a fewer number of topics overall (B = −0.286, 95% CI = −0.426 to −0.147) and were less likely to report receipt of instruction on each of six topic areas adjusting for covariates (i.e., significant path a in Figure 1). In turn, the more topics received (B = 0.188, 95% CI = 0.055 to 0.321) and receipt of instruction about birth control methods, where to get birth control, STIs, and HIV/AIDS predicted a higher likelihood of contraceptive use adjusting for covariates (i.e., significant path b).

Table 3.

Mediation Models on the Receipt of Formal Sex Education Before First Intercourse in the Association between Cognitive Disability and Contraceptive Use at First Intercourse, National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) 2011–2017

| Analysis | Point Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | Effect Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediator 1: Number of sex education topics received | |||

| Cognitive disability → Number of topics | −0.286 | [−0.426, −0.147] | |

| Number of topics → Contraception | 0.188 | [0.055, 0.321] | |

| Cognitive disability → Contraception (indirect or mediation effect) | −0.009 | [−0.017, −0.002] | 0.200 |

| Mediator 2: How to say no to sex | |||

| Cognitive disability → Say no to sex | −0.553 | [−0.885, −0.220] | |

| Say no to sex → Contraception | 0.139 | [−0.153, 0.432] | |

| Cognitive disability → Contraception | −0.003 | [−0.009, 0.003] | |

| Mediator 3: Birth control method | |||

| Cognitive disability → Birth control | −0.387 | [−0.696, −0.078] | |

| Birth control → Contraception | 0.415 | [0.132, 0.698] | |

| Cognitive disability → Contraception | −0.007 | [−0.016, −0.001] | 0.164 |

| Mediator 4: Where to get birth control | |||

| Cognitive disability → Where to get | −0.446 | [−0.766, −0.126] | |

| Where to get → Contraception | 0.327 | [0.051, 0.602] | |

| Cognitive disability → Contraception | −0.008 | [−0.014, −0.001] | 0.181 |

| Mediator 5: How to use condom | |||

| Cognitive disability → Condom use | −0.570 | [−0.873, −0.266] | |

| Condom use → Contraception | 0.212 | [−0.061, 0.486] | |

| Cognitive disability → Contraception | −0.006 | [−0.014, 0.002] | |

| Mediator 6: Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs) | |||

| Cognitive disability → STI | −0.586 | [−0.943, −0.229] | |

| STI → Contraception | 0.390 | [0.068, 0.723] | |

| Cognitive disability → Contraception | −0.006 | [−0.013, −0.001] | 0.135 |

| Mediator 7: How to prevent HIV/AIDS | |||

| Cognitive disability → HIV/AIDS | −0.562 | [−0.889, −0.235] | |

| HIV/AIDS → Contraception | 0.297 | [0.006, 0.589] | |

| Cognitive disability → Contraception | −0.005 | [−0.012, −0.000] | 0.119 |

Note. We used z-scores for the number of sex education topics received. Effect ratios, or proportions of total effect mediated, were presented only when mediation effects were significant at p < .05. Models were adjusted for age, age at first intercourse, place of birth, race, poverty status, residence area, living arrangement up to age 14, family religion, religious service attendance at age 14, and sex education received from a parent. Paths from formal sex education to contraception were additionally adjusted for the nature of relationships with first sexual partner.

Given the significant paths a and b, we found significant indirect effects of cognitive disabilities on contraceptive use via reported receipt of a greater number of instructional topics (B = −0.009, 95% CI = −0.017 to −0.002) and instruction about birth control methods (B = −0.007, 95% CI = −0.016 to −0.011), where to obtain birth control (B = −0.008, 95% CI = −0.014 to −0.001), STIs (B = −0.006, 95% CI = −0.013 to −0.001), and HIV/AIDS (B = −0.005, 95% CI = −0.012 to −0.000). In total, 11.9% (HIV/AIDS) to 20.0% (total number of topics) of the total effect of cognitive disabilities on contraceptive use was mediated through reported receipt of formal sex education.

3.3.2. Women with non-cognitive disabilities

Women with non-cognitive disabilities and those without disabilities reported receiving a similar number of instructional topics (B = −0.020, 95% CI = −0.167 to 0.127). Indirect effect of sex education in the association between non-cognitive disability and contraceptive use was not evident (B = −0.001, 95% CI = −0.001 to 0.004 in case of the number of instructional topics).

3.4. Sensitivity analysis

Among women who reported voluntary and involuntary first sexual intercourse (n = 3,134), women with cognitive disabilities were approximately twice as likely to report involuntary first intercourse than their nondisabled counterparts (11.3% vs. 5.5%, p < .01). Women with cognitive disabilities also reported higher rates of contraceptive nonuse at first intercourse than nondisabled women (30.0% vs. 21.1%); this difference remained significant after controlling for covariates (aOR = 0.72, 95% CI = 0.51 to 0.99). Similar to the main analysis, 10.1% to 17.5% of the total effect of cognitive disabilities on contraceptive use was mediated through reported receipt of formal sex education. No statistically significant associations between non-cognitive disability and contraceptive use, and the mediating role of formal sex education in the associations, were detected, consistent with the main findings.

4. Discussion

Using a large nationally representative sample, we examined the association between young women’s disability status and their contraceptive use at first voluntary intercourse and explored whether formal sex education before first intercourse contributes to this association. In contrast to prior studies [7, 12], the greater risk of contraceptive nonuse among women with cognitive or non-cognitive disabilities compared to nondisabled women was not evident in our analysis. This inconsistency may partly reflect that, unlike earlier studies, we were able to account for the voluntary nature of sexual intercourse among women with and without disabilities. In our sensitivity analysis with all women regardless of the voluntary nature of the intercourse, women with cognitive disabilities were less likely to report contraceptive use at first intercourse than their nondisabled peers. Thus, our finding suggests the importance of understanding the voluntary nature of sexual intercourse when examining contraceptive use and unintended pregnancy in women with and without disabilities.

We also found that women with cognitive disabilities received instruction on a fewer number of topics overall and were less likely to report receiving instruction in each of the six topics than nondisabled women, suggesting barriers exist to sex education access among women with cognitive disabilities. On the other hand, women with non-cognitive disabilities showed similar levels of access to formal sex education and contraceptives compared to nondisabled women [4, 7]; thus, having a disability does not necessarily preclude access to formal sex education and contraception, and it may depend on the type or nature of disabilities. Future research is needed to better understand how and in what ways young women with various types of disabilities and degrees of impairment show differences in access to formal sex education and contraceptive use, and thus to provide more accessible, comprehensive sex education for all young women [1]. Given that more than one in ten women with cognitive disabilities reported their first sexual intercourse was involuntary, future research is also needed among a larger sample of women with cognitive (and non-cognitive) disabilities to better understand the associations between the forced sex, formal sex education, and contraceptive use and to identify differential predictors of contraceptive use among those who are exposed to sexual coercion and those who are not.

Findings from the mediation analysis suggest that the differences in contraceptive use between young women with cognitive disabilities and those without disabilities may be attributable, in part, to differences in the reported receipt of formal sex education. While the need for formal sex education in special education settings is widely acknowledged, many special education teachers report feeling unprepared to provide instruction, and thus only a modest amount of education is provided to the students [1, 31]. Enhancing the capacity of special education teachers to provide sex education and supporting collaboration between sexual health educators and special education teachers is warranted. It is equally important to prepare healthcare professionals to discuss sexual health with patients with disabilities, particularly given the frequency of interactions between healthcare providers and young women with disabilities [32]. As important as ensuring access to comprehensive sex education, research to develop and test the efficacy and suitability of sex education curricula is needed to meet the unique needs and skillsets of youth with disabilities. Strategies to improve their retention of the content are integral to these efforts [33].

The partial mediation effect (i.e., up to 20.0% of total effects mediated) suggests that barriers other than poor access to formal sex education, such as access to contraceptives, may be critical mechanisms linking disability to contraceptive nonuse. Women with cognitive disabilities may be unable to afford contraceptives, need assistance from others to obtain contraceptives, and not be expected to engage in sexual activity by healthcare professionals [1, 6, 32]. Collectively, these factors may prevent women with cognitive disabilities from accessing and using contraception. Further research is needed to explore other mechanisms that may contribute to increasing contraceptive use among young women with cognitive disabilities.

This research has several limitations. First, we were unable to ascertain the quantity and quality of the sex education instruction received. Second, some women with disabilities may be precluded from survey participation due to their functional barriers [34], and if so, our results may underestimate the differences by disability status. Third, the NSFG’s disability measure does not provide specific information on the onset, length, or severity of disabilities. In particular, disabilities could have occurred after the receipt of sex education and/or first sexual intercourse. Fourth, survey responses may be subject to recall bias, especially for those with cognitive disabilities. Finally, the NSFG’s cross-sectional design hampered our ability to determine the temporal sequence of disability, formal sex education, and contraceptive use.

There are several policy implications of this study. The sex education curriculum at school should be evaluated to assess whether it is comprehensive and inclusive of special education students or those with disabilities. It may be particularly important to provide formal sex education at an earlier age as adolescents with disabilities are likely to experience first intercourse earlier than their nondisabled peers, and they are exposed to a higher risk of sexual violence or forced intercourse [23, 24]. It is also important to strengthen other opportunities and means of delivering formal sex education, including education in health care settings [1].

Implications.

Young women with cognitive disabilities are less likely to report receipt of formal sex education before first voluntary intercourse than their nondisabled peers, which in part, contributes to their lower likelihood of contraceptive use at first intercourse. Increased and earlier access to sex education may help promote contraceptive use among women with disabilities.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This work was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration [R40MC307540100]; the National Institutes of Health Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development [R01HD082105]; and the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research, US Department of Health & Human Services [90AR5024-01-00, 90DPGE000101].

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Health Resources and Services Administration, National Institutes of Health, or National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research.

Declaration of Competing Interest

None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Holland-Hall C, Quint EH. Sexuality and disability in adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am 2017;64:435–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wienholz S, Seidel A, Michel M, Haeussler-Sczepan M, Riedei-Heller S. Sexual experiences of adolescents with and without disabilities: Results from a cross-sectional study. Sex Disabil 2016;34:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kahn NF, Halpern CT. Experiences of vaginal, oral, and anal sex from adolescence to early adulthood in populations with physical disabilities. J Adolesc Health 2018;62:294–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Cheng MM, Udry JR. Sexual behaviors of physically disabled adolescents in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2002;31:48–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Suris J, Resnick M, Cassuto N, Blum R. Sexual behavior of adolescents with chronic disease and disability. J Adolesc Health 1996;19:124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Shandra C, Chowdhury A. The first sexual experience among adolescent girls with and without disabilities. J Youth Adolesc 2012;41:515–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cheng MM, Udry JR. Sexual experiences of adolescents with low cognitive abilities in the U.S. J Dev Phys Disabil 2005;17:155–172. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mandell DS, Eleey CC, Cederbaum JA, Noll E, Hutchinson MK, Jemmott LS, et al. Sexually transmitted infection among adolescents receiving special education services. J Sch Health 2008;78:382–388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Bernert DJ, Ding K, Hoban MT. Sexual and substance use behaviors of college students with disabilities. Am J Health Behav 2012;36:459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mitra M, Clements KM, Zhang J, Lezzoni LI, Smeltzer SC, Long-Bellil LM. Maternal characteristics, pregnancy complications and adverse birth outcomes among women with disabilities. Med Care 2015;53:1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Wu JP, McKee KS, McKee MM, Meade MA, Plegue MA, Sen A. Use of reversible contraceptive methods among US women with physical or sensory disabilities. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2017;49:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wu J, Zhang J, Mitra M, Parish SL, Minama Reddy GK. Provision of moderately and highly effective reversible contraception to women with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Evidence from the Massachusetts all-payer claims database. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Mosher W, Hughes R, Bloom T, Horton L, Mojtabai R, Alhusen JL. Contraceptive use by disability status: new national estimates from the National Survey of Family Growth. Contracept 2018;97:552–558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lindberg LD, Maddow-Zimet I. Consequences of sex education on teen and young adult sexual behaviors and outcomes. J Adolesc Health 2012;51:332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mueller TE, Gavin LE, Kulkarni A. The association between sex education and youth’s engagement in sexual intercourse, age at first intercourse, and birth control use at first sex. J Adolesc Health 2008;42:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Barnard-Brak L, Schmidt M, Chesnut S, Wei T, Richman D. Predictors of access to sex education for children with intellectual disabilities in public schools. Intellect Dev Disabil 2014;52:85–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Manlove J, Ryan S, Franzetta K. Patterns of contraceptive use within teenagers’ first sexual relationships. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2003;35:246–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Manning WD, Longmore MA, Giordano PC. The relationship context of contraceptive use at first intercourse. Fam Plann Perspect 2000:104–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Kirby D Antecedents of adolescent initiation of sex, contraceptive use, and pregnancy. Am J Health Behav 2002;26:473–485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jaramillo N, Buhi E, Elder J, Corliss HL. Associations between sex education and contraceptive use among heterosexually active, adolescent males in the United States. J Adolesc Health 2017;60:534–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Lepkowski JM, Mosher WD, Davis KE, Groves RM, Van Hoewyk J. National Survey of Family Growth: Sample design and analysis of a continuous survey. Vital Health Stat 2. 2010;150:1–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].National Center for Health Statistics. 2011–2013 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG): Summary of design and data collection methods. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Casteel C, Martin SL, Smith JB, Gurka KK, Kupper LL. National study of physical and sexual assault among women with disabilities. Inj Prev 2008;14:87–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Martin SL, Ray N, Sotres-Alvarez D, Kupper LL, Moracco KE, Dickens PA, et al. Physical and sexual assault of women with disabilities. Violence against Women 2006;12:823–837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Glei DA. Measuring contraceptive use patterns among teenage and adult women. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999. March-April;31(2):73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Bureau UC. How disability data are collected from the American Community Survey, https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-collection-acs.html [accessed 29 August 2018].

- [27].Li H, Mitra M, Wu JP, Parish SL, Valentine A, Dembo RS. Female sterilization and cognitive disability in the United States, 2011–2015. Obstet Gynecol 2018;132:559–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Trussell J Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception 2011;83:397–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hicks R, Tingley D. Causal mediation analysis. Stata Journal 2011;11:605. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Imai K, Keele L, Tingley D, Yamamoto T. Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. Am Polit Sci Rev 2011;105:765–789. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Howard- Barr EM, Rienzo BA, Pigg RM Jr, James D. Teacher beliefs, professional preparation, and practices regarding exceptional students and sexuality education. J Sch Health 2005;75:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Breuner CC, Mattson G, Committee on Adolescence, Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. Sexuality education for children and adolescents. Pediatr 2016;138:e20161348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Schaafsma D, Kok G, Stoffelen JM, Curfs LM. Identifying effective methods for teaching sex education to individuals with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review. J Sex Res 2015;52(4):412–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Parsons JA, Baum S, Johnson TP. Inclusion of Disabled Populations in Social Surveys: Review and Recommendations. Survey Research Laboratory, University of Illinois for the National Center for Health Statistics, 2000. [Google Scholar]