Abstract

Background

The early integration of supportive care in oncology improves patient‐centered outcomes. However, data are lacking regarding how to achieve this in resource‐limited settings. We studied whether patient navigation increased access to multidisciplinary supportive care among Mexican patients with advanced cancer.

Materials and Methods

This randomized controlled trial was conducted between August 2017 and April 2018 at a public hospital in Mexico City. Patients aged ≥18 years with metastatic tumors ≤6 weeks from diagnosis were randomized (1:1) to a patient navigation intervention or usual care. Patients randomized to patient navigation received personalized supportive care from a navigator and a multidisciplinary team. Patients randomized to usual care obtained supportive care referrals from treating oncologists. The primary outcome was the implementation of supportive care interventions at 12 weeks. Secondary outcomes included advance directive completion, supportive care needs, and quality of life.

Results

One hundred thirty‐four patients were randomized: 67 to patient navigation and 67 to usual care. Supportive care interventions were provided to 74% of patients in the patient navigation arm versus 24% in usual care (difference 0.50, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.34–0.62; p < .0001). In the patient navigation arm, 48% of eligible patients completed advance directives, compared with 0% in usual care (p < .0001). At 12 weeks, patients randomized to patient navigation had less moderate/severe pain (10% vs. 33%; difference 0.23, 95% CI 0.07–0.38; p = .006), without differences in quality of life between arms.

Conclusion

Patient navigation improves access to early supportive care, advance care planning, and pain for patients with advanced cancer in resource‐limited settings.

Implications for Practice

The early implementation of supportive care in oncology is recommended by international guidelines, but this might be difficult to achieve in resource‐limited settings. This randomized clinical trial including 134 Mexican patients with advanced cancer demonstrates that a multidisciplinary patient navigation intervention can improve the early access to supportive and palliative care interventions, increase advance care planning, and reduce symptoms compared with usual oncologist‐guided care alone. These results demonstrate that patient navigation represents a potentially useful solution to achieve the adequate implementation of supportive and palliative care in resource‐limited settings globally.

Keywords: Palliative care, Patient navigation, Advance directives, Symptom assessment, Health resources, Developing countries

Short abstract

Patient navigation assists patients in overcoming barriers to care, but its use is under‐used in resource‐limited settings. This article examines whether a patient navigator‐led intervention could improve early access to multidisciplinary supportive and palliative care among Mexican patients with metastatic solid tumors.

Introduction

Palliative care can improve the quality of life (QoL) of patients through the prevention and relief of suffering by managing pain and other physical, psychosocial, and spiritual problems [1]. Approximately 17 million people with cancer are in need of supportive and palliative care, of whom almost 80% live in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMIC) [2]. The early provision of palliative care can improve QoL, symptoms, advance care planning, and survival among patients with advanced cancer, and the American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO), among others, has recommended implementing multidisciplinary specialized supportive and palliative care early in the course of the disease [1, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Unfortunately, this early integration of supportive and palliative care seldom happens in LMIC owing to a lack of training and infrastructure, and most palliative care interventions are provided near the end of life [7, 8]. In Mexico, as in other LMIC, less than 50% of patients with advanced cancer receive supportive care consultations and have discussions regarding end‐of‐life care and advance care planning in the first year after diagnosis [9]. This leads to late referrals to palliative care services, with an average time from first palliative care visit to death of approximately 14 days [9].

Novel strategies are needed in order to achieve the early integration of supportive and palliative care into everyday oncology practice [10]. One potential solution is patient navigation, which can improve access to cancer care across various settings, including screening, diagnosis, and treatment [5, 11]. A patient navigator (PN) can be a lay health worker or a professional health worker, like a nurse, psychologist, or social worker, who assists patients in overcoming barriers to care. Although patient navigation has been tested as a tool to improve specific aspects of supportive care (such as advance directives [AD] completion) in LMIC and among disadvantaged populations in high‐income countries (HIC), it has not been used to improve the coordinated and early delivery of multidisciplinary supportive and palliative care interventions in resource‐limited settings [12].

In this randomized controlled trial (RCT), we examined whether a PN‐led multidisciplinary intervention could improve early access to multidisciplinary generalist supportive and palliative care among Mexican patients with metastatic solid tumors compared with usual oncological care alone. In addition, we explored if the intervention led to improvements in symptoms, QoL, and engagement in advance care planning.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This RCT included patients with metastatic solid tumors from the oncology clinics at Instituto Nacional de Ciencias Médicas y Nutrición Salvador Zubirán (INCMNSZ), a public hospital in Mexico City. The study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines. The study protocol was approved by INCMNSZ's Institutional Review Board, and the trial was registered in Clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03293849).

Participants

Eligible patients were aged ≥18 years, had diagnosis of metastatic solid tumors, spoke Spanish, and were ≤ 6 weeks from diagnosis. Consecutive patients fulfilling inclusion criteria were approached by research assistants, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants. We excluded patients with hematological malignancies, as well as those planning to undergo treatment at another institution.

Randomization

After completing informed consent, patients were randomized in a 1:1 fashion to the PN‐led supportive care multidisciplinary intervention or usual oncological care alone. Randomization was conducted using a random‐number table without stratification or blocking. The allocation sequence was available only to one of the researchers and was unknown to those undertaking the recruitment process. Owing to the type of interventions, blinding of participants and/or researchers was not possible.

Procedures

After randomization, patients completed a series of validated questionnaires using an electronic tablet with help from a research assistant. The questionnaires were administered in a private room at the oncology clinic once the patients were aware of their diagnosis. Sociodemographic data and barriers for accessing health care (such as financial, transportation, or caregiving issues) were obtained. All patients completed the Spanish versions of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – General (FACT‐G) QoL questionnaire and the Patient Health Questionnaire‐2 (PHQ‐2) depression screener, and the Palliative Performance Scale (PPS, which provides an estimation of life expectancy) was calculated [13, 14, 15]. FACT‐G includes 27 five‐point Likert‐type questions in four subscales: Physical, Social/Family, Emotional, and Functional Well‐Being [13]. Depending on answers to specific FACT‐G questions, patients completed additional questionnaires assessing various symptoms such as pain, caregiver burden, depression, and anxiety (Fig. 1A) [14, 16, 17, 18]. “Triggers” for additional questionnaires were predefined by supportive and palliative care experts before study initiation, taking into account actionable symptoms and international guidelines. Patients aged ≥65 years completed the G8 screening tool, designed to determine which older adults with cancer require additional geriatric assessments [19].

Figure 1.

Assessments and interventions utilized for the study. (A): Initial assessments and subsequent questionnaires, including triggers for their use. (B): The set of suggested interventions and referrals included in the personalized plan created after the multidisciplinary team meeting.Abbreviations: FACT‐G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General; GAD‐7, General Anxiety Disorder‐7; PHQ‐2, Patient Health Questionnaire‐2; PHQ‐9, Patient Health Questionnaire‐9; PPS, Palliative Performance Scale.

Assessments from patients in both groups were provided to the PN (a psychologist with training in patient navigation and palliative care), who reviewed, summarized, and presented them at weekly 1‐hour meetings with a multidisciplinary team composed of an oncologist, a pain and palliative care physician, a psychologist, and a physical therapist. After reviewing the assessments, a written personalized intervention plan was designed taking into account each patient's specific needs (Fig. 1B). Patients with a life expectancy of ≤6 months according to the PPS were deemed candidates for completing AD in accordance with Mexican law, which allows patients with limited life expectancy to sign AD without a notary public [20].

Patients allocated to the PN‐led intervention met with the PN during a clinical visit following the multidisciplinary team meeting. The personalized intervention plan was presented and explained to the patient and his/her relatives, and the PN arranged for interventions, which were accepted by the patient to take place on the same day as oncology visits and/or treatment appointments. During the first visit, the PN addressed barriers for accessing health care (including transportation, financial constraints, fear, communication issues, etc.) and provided information and resources to overcome them. In addition, the PN explored prognostic understanding, helped clarify treatment goals, and provided assistance with medical decision‐making. At the first subsequent visit, the PN discussed advance care planning and attempted to obtain a written AD from eligible patients. The PN followed up with the patients telephonically once per week in order to detect new barriers or issues. Specific interventions aimed at addressing the patients’ symptoms and supportive care needs were up to each of the multidisciplinary team members, and no fixed number of appointments was mandated.

Patients allocated to usual oncological care alone did not meet with the PN and received care from their treating oncologist, who was responsible for assessing symptoms and supportive care needs and for undertaking necessary referrals. As per the usual care at INCMNSZ, patients are not routinely evaluated by supportive care professionals, the existing palliative care service is only available on demand and not exclusive for patients with cancer, and patients with a limited life expectancy do not routinely complete AD [9]. The treating oncologist was not provided information regarding the multidisciplinary team meeting, the questionnaires, or the personalized intervention plan. Patients with severe pain and/or suicidal ideation were reported to the treating oncologist and offered interventions.

At 12 weeks’ follow‐up, patients completed the same set of questionnaires during a clinic visit with the help of a research assistant. The PN once again presented this information at the multidisciplinary team meeting, and additional interventions were proposed as needed. At this time, patients randomized to usual oncological care alone were able to receive multidisciplinary supportive and palliative care interventions from the PN and the multidisciplinary team in the same way as patients randomized to the PN‐led intervention.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was the implementation of supportive and palliative care interventions, defined as the proportion of patients who agreed to participate, completed initial assessments, met with the PN to discuss advance care planning, and obtained the recommended interventions within 12 weeks from enrollment. This measure of intervention delivery and process outcome was chosen in order to assess the feasibility of providing early supportive care through patient navigation, in accordance with ASCO guidelines [6, 7, 10].

Protocol‐specified secondary outcomes reported here include rate of implementation of each supportive and palliative care intervention; rate of AD completion; differences in QoL between groups at 12 weeks; and differences in supportive care needs between groups at 12 weeks. Additional endpoints not reported here include health care use, chemotherapy use at the end of life, and survival.

Statistical Analysis

With 61 patients per arm, the study had an 80% power to detect a 25% difference in implementation of supportive care interventions between arms (considering a predicted proportion of 55% in the usual oncological care alone arm) with a two‐sided α of 0.05.

Descriptive statistics were used to estimate frequencies, means, and SDs. Differences between groups in access to supportive care interventions, AD completion, and supportive care needs were assessed using two‐sided Fisher's exact tests, chi‐squared test, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for categorical variables. Independent‐samples Student's t test was used to assess continuous variables, including the comparison of QoL measurements between the two groups at 12 weeks.

For QoL measurements, we used the total FACT‐G score (0–100), as well as each subscale's score (0–25). We used changes in FACT‐G scores from baseline to 12 weeks to categorize patients into those with worsening QoL (≥10‐point decrease), improvement in QoL (≥6‐point increase), and minimal/no change (between <10‐point decrease and < 5‐point increase) [21].

All analyses were performed using STATA software, version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Patient Characteristics

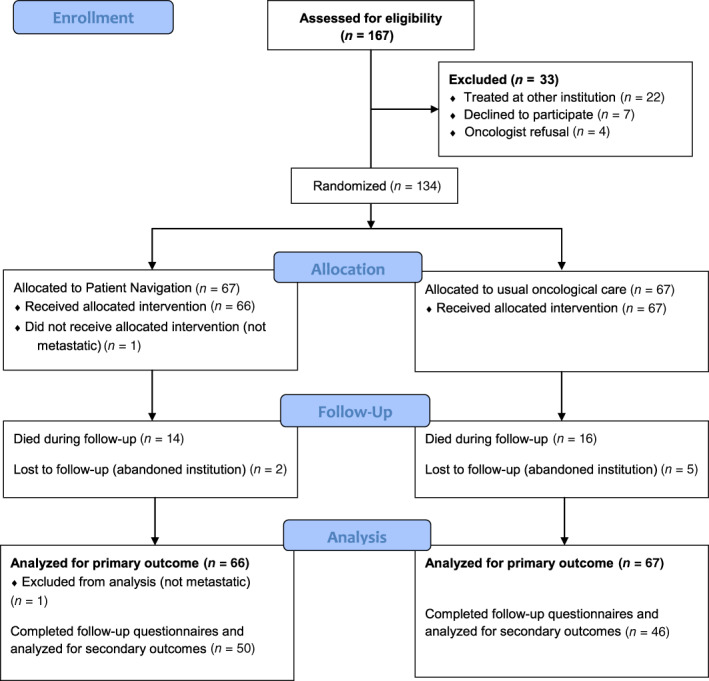

Between August 4, 2017, and April 20, 2018, 134 patients were enrolled in the study, and 133 were analyzed for the primary outcome (Fig. 2). Baseline patient characteristics and supportive and palliative care needs are shown in Table 1. Among included patients, 78% (n = 105) reported at least one barrier for accessing supportive care, with a median number of patient‐reported barriers of one (range 0–8). The most common barriers were financial constraints (63%, n = 83), beliefs associated with cancer and its treatment (38%, n = 50), transportation‐related issues (29%, n = 38), fear (24%, n = 31), and distance to the treatment center (22%, n = 29). Thirty patients died within the first 12 weeks (14 in the PN‐led intervention arm vs. 16 in the usual oncological care alone arm, p = .185) and 7 were lost to follow‐up (2 in the PN‐led intervention arm vs. 5 in the usual oncological care alone arm, p = .45). Median follow‐up was 89.5 days (range 7–112 days). Ninety‐six patients completed the 12‐week follow‐up questionnaires and were evaluable for secondary outcomes (differences in QoL, supportive and palliative care needs, and symptoms).

Figure 2.

CONSORT diagram.

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics, supportive and palliative care needs, and quality of life

| Characteristic | Patient navigation (n = 66) | Usual care (n = 67) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (SD) | 61.8 (14.2) | 59.2 (13.1) |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 35 (53) | 34 (51) |

| Lives in rural area, n (%) | 6 (9) | 8 (12) |

| Unemployed/self‐employed, n (%) | 50 (76) | 45 (67) |

| Uninsured, n (%) | 58 (88) | 60 (90) |

| Monthly income <$600 USD, n (%) | 28 (43) | 41 (61) |

| Educational level, n (%) | ||

| Middle school or less | 30 (45) | 27 (40) |

| High school or higher | 36 (55) | 40 (60) |

| Tumor types, n (%) | ||

| Hepatopancreatobiliary | 21 (32) | 23 (34) |

| Other gastrointestinal | 17 (26) | 13 (20) |

| Genitourinary | 10 (15) | 10 (15) |

| Breast | 5 (7) | 7 (11) |

| Gynecological | 2 (3) | 3 (4) |

| Lung | 2 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Others | 9 (14) | 9 (13) |

| Supportive and palliative care needs and symptoms, n (%) | ||

| Moderate/severe pain | 28 (42) | 32 (47) |

| Screening positive for depression or anxiety | 51 (77) | 51 (75) |

| Suicidal ideation | 3 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Moderate/severe fatigue | 44 (66) | 43 (64) |

| Caregiver burden | 19 (29) | 12 (18) |

| Sleep disturbance | 39 (59) | 40 (60) |

| Life expectancy ≤6 months | 29 (44) | 31 (46) |

| Geriatric screening positive | 21 (32) | 16 (24) |

| Quality of life (FACT‐G scores), mean (95% CI) | ||

| Overall | 68.9 (64.6–73.2) | 67.4 (63.2–71.7) |

| Physical well‐being | 19.0 (17.3–20.6) | 18.5 (16.9–20.0) |

| Social/family well‐being | 19.5 (18.3–20.7) | 19.6 (18.2–21.0) |

| Emotional well‐being | 15.8 (14.6–16.9) | 15.9 (14.7–17.0) |

| Functional well‐being | 14.7 (13.1–16.2) | 13.5 (11.9–15.2) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; FACT‐G, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy‐General.

Implementation of Supportive and Palliative Care Interventions

Ninety‐four percent of patients assigned to the PN‐led intervention (n = 62, 95% CI 85%–98%) met with the PN to discuss advance care planning and supportive and palliative care interventions. Median time from recruitment to first PN appointment was 12.5 days (range 4–75). Supportive and palliative care interventions were recommended for 56 patients in the PN‐led intervention arm (84.8%), of whom 49 received at least one, with an implementation rate of 87% (95% CI 76%–93%). Supportive and palliative care interventions were recommended for 59 patients in the usual oncological care alone arm (88%), of whom 16 received at least one, with an implementation rate of 27% (95% CI 17%–39%). The median number of recommended interventions was three (range 0–6) for both arms. In the intention‐to‐treat analysis, the implementation of all recommended interventions was significantly higher in the PN‐led intervention arm than in the oncological care alone arm (Table 2).

Table 2.

Implementation of supportive and palliative care interventions in the intention‐to‐treat population (chi‐squared test)

| Interventions | Patient navigation (n = 66) | Usual oncological care (n = 67) | Difference (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Implemented, n (%) | Implemented, n (%) | |||

| Any supportive and palliative care intervention | 49 (74.2) | 16 (23.9) | 0.50 (0.34–0.62) | <.0001 |

| Psychology | 37 (56.1) | 1 (1.5) | 0.54 (0.41–0.66) | <.0001 |

| Physical and occupational therapy | 32 (48.5) | 0 (0) | 0.48 (0.36–0.60) | <.0001 |

| Pain and palliative care clinic | 23 (34.9) | 10 (14.9) | 0.20 (0.05–0.34) | .0078 |

| Geriatrics | 17 (25.7) | 4 (5.9) | 0.20 (0.08–0.32) | .0018 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

AD Completion

Among all enrolled patients, 59 (44%) had a calculated life expectancy of ≤6 months and were eligible for AD completion. In the PN‐led intervention arm, AD completion was recommended for 29 patients (43.9%), of whom 14 completed them, for an implementation rate of 48% (95% CI 31%–65%). In the usual oncological care alone arm, AD completion was recommended for 30 patients (44.8%), of whom none completed them (p < .001).

Changes in QoL and Supportive and Palliative Care Needs

Baseline QoL was similar between arms (Table 1), and both arms showed improvement in QoL scores at 12 weeks. At 12 weeks, we found no differences in FACT‐G scores between patients assigned to the PN‐led intervention or to usual oncological care alone, and this was also true for each of the FACT‐G subscales (Table 3). Among patients in the PN‐led intervention arm, 38% (n = 19) had significant improvement in QoL at 12 weeks, 16% (n = 8) had significant worsening, and 46% (n = 23) had no change, whereas among those allocated to usual oncological care alone, 44% (n = 20) had significant improvement in QoL at 12 weeks, 11% (n = 5) had significant worsening, and 45% (n = 23) had no change (p = .72).

Table 3.

Differences in quality of life between groups at 12 weeks’ follow‐up

| Quality of life domain | 12 weeks’ follow‐up, mean (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient navigation (n = 50) | Usual care (n = 46) | Difference | p value | |

| FACT‐G total score | 76.0 (71.7 to 80.2) | 76.3 (71.7 to 80.9) | 0.3 (−5.8 to 6.5) | .45 |

| Physical well‐being | 20.3 (18.8 to 21.8) | 20.8 (19.1 to 22.5) | 0.5 (−1.8 to 2.7) | .34 |

| Social/family well‐being | 20.8 (19.5 to 22.0) | 20.2 (18.9 to 21.5) | −0.6 (−2.4 to 1.2) | .74 |

| Emotional well‐being | 18.4 (17.1 to 19.7) | 17.8 (16.6 to 19.1) | −0.6 (−2.4 to 1.2) | .74 |

| Functional well‐being | 16.4 (14.7 to 18.1) | 17.5 (15.9 to 19.0) | 1.0 (−1.3 to 3.3) | .18 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Supportive and palliative care needs for patients in both study arms at 12 weeks are shown in Table 4. Patients allocated to the PN‐led intervention were significantly less likely to report moderate/severe pain at 12 weeks (10% vs. 33%, p = .006). There were no significant differences in other supportive and palliative care needs and symptoms.

Table 4.

Differences in supportive and palliative care needs and symptoms between groups at 12 weeks’ follow‐up

| Need/symptom | Patient navigation (n = 50), n (%) | Usual care (n = 46), n (%) | Difference (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moderate/severe pain | 5 (10) | 15 (33) | 0.23 (0.07 to 0.38) | .006 |

| Screening positive for depression or anxiety | 24 (48) | 20 (43) | 0.05 (−0.14 to 0.24) | .62 |

| Suicidal ideation | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.01 (−0.06 to 0.09) | .48 |

| Moderate/severe fatigue | 24 (48) | 24 (52) | 0.04 (−0.15 to 0.23) | .69 |

| Caregiver burden | 8 (16) | 10 (22) | 0.06 (−0.10 to 0.22) | .45 |

| Sleep disturbance | 20 (40) | 24 (52) | 0.12 (−0.08 to 0.30) | .24 |

| Life expectancy ≤6 months | 19 (38) | 16 (35) | 0.03 (−0.15 to 0.21) | .76 |

| Geriatric screening positive | 8 (16) | 9 (20) | 0.04 (−0.11 to 0.20) | .61 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Discussion

A PN‐led multidisciplinary intervention significantly improved access to supportive and palliative care among Mexican patients with metastatic solid tumors compared with usual oncological care alone. In addition, the PN‐led intervention significantly increased AD completion and decreased the proportion of patients reporting moderate/severe pain. The intervention did not significantly improve QoL compared with usual oncological care alone at 12 weeks’ follow‐up.

The early integration of supportive and palliative care into oncology has been advocated by international guidelines, because it leads to improvements in QoL, advance care planning, patient‐reported symptoms, and survival [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 22]. However, most RCTs of early palliative care were conducted in cancer centers located in HIC, where patients obtained palliative care from specialized physicians and nurses [23, 24]. Unfortunately, this may not always be feasible in resource‐limited settings, where palliative care services are not cancer specific, severely underused, or nonexistent [2, 7, 9, 10, 25]. Currently, there is little understanding of how to deliver supportive and palliative care interventions effectively in diverse settings and within the wide range of existing health systems, and in order to bridge this gap, the World Health Organization has recommended conducting practical real‐world implementation research [26].

In this trial, patient navigation improved the delivery of personalized supportive and palliative care in a setting with limited resources. In contrast with other studies, interventions were triggered by the patients’ needs identified through validated screening tools, which were reviewed by a multidisciplinary team [23]. This strategy was adopted in order to reduce patient and provider burden by focusing on specific patient‐reported symptoms and needs, making the results easier to implement in real‐world settings. As an example, although a pain and palliative care specialist was available, only one third of patients in the intervention arm required this type of intervention, whereas the rest were adequately managed by the other team members. One relevant finding was the high AD completion rate (44%), which is comparable to that found among Hispanics in the U.S. and significantly higher than that in the control arm [5, 27]. Although AD have been part of the Mexican legislation since 2012, their implementation has been slow, and only about 10,000 AD have been completed in Mexico City, where more than 12,000 people die of cancer every year [28, 29]. Our study is the first to show that patient navigation can improve the completion of AD in Latin America and provides data supporting the creation of legislation aimed at making AD available for patients across the region.

In contrast with other studies, QoL at 12 weeks was similar between patients randomized to the PN‐led intervention and those receiving usual oncological care alone [4, 22]. Although our trial was not powered to detect differences in QoL, it is important to mention that at least three meta‐analyses have shown a relatively small improvement in QoL with early supportive and palliative care, which is driven by trials including specialized, rather than generalist, palliative care interventions [23, 24, 30]. In our study, both arms had a relevant improvement in QoL at 12 weeks, which is similar to that reported previously in an RCT of early supportive care among patients with gastrointestinal malignancies [31]. Because our study was conducted at a single institution, it is possible that oncologists provided some interventions themselves to patients enrolled in the usual oncological care alone arm as a consequence of being observed.

This study has limitations. Patients with all tumor types were included, and a significant proportion had hepatopancreatobiliary tumors, for which the benefit of early supportive and palliative care on QoL is unclear [31]. Although these could be considered limitations, our results show that access to early supportive and palliative care and advance care planning can be improved through patient navigation regardless of the type of disease, even among patients facing several barriers for accessing health care in a resource‐limited setting. In addition, we did show improvement in relevant patient‐centered outcomes, such as pain, which is not necessarily reflected in QoL measured through standardized questionnaires [32]. Likewise, the timing and type of interventions provided by the multidisciplinary team were not prespecified, and each provider was able to decide what to offer each patient. Although this may limit the replication of the results, we believe it is one of the study's strengths because provided interventions were pragmatic and institutions with limited resources could adopt this model without undertaking major organizational changes. Our study had a relatively short follow‐up time of 12 weeks, and differences in QoL and other outcomes among groups could have been found with longer follow‐up [22]. In our study, patient navigation was provided by a single navigator (with training in psychology) at a single institution, which may limit the generalizability of the results and introduce bias. Although the use of patient navigation for supportive care in resource‐limited settings should be studied in future multi‐institutional trials, we believe that the profile and training of the study's PN (psychologist, social worker) is widely available and replicable across various settings, and results should be similar across diverse health care systems and similar institutions. In addition, it is possible that more brief and simpler tools could be used to assess supportive care needs and make the intervention easier to complete. Finally, although these findings may be applicable across many middle‐income nations, the infrastructure necessary may not be available in low‐income countries, and thus, different models of care (such as community health care workers) may be more appropriate in those settings.

Conclusion

Currently, the question facing supportive and palliative care research is not whether its integration into usual oncology care is useful but rather how this can be accomplished to optimize existing resources and to provide the highest‐quality patient‐centered care [10, 26]. Our study shows that patient navigation can significantly improve access to early supportive and palliative care, advance care planning, and pain control for patients with cancer treated in resource‐limited settings using existing services and resources. Future studies using patient navigation to improve the provision of early supportive and palliative care should aim at improving the selection of patients and the delivery of specific interventions in order to focus resources toward those most likely to benefit. The implementation of patient navigation should be strongly considered by institutions with limited resources—in both LMIC and HIC—aiming to achieve the early integration of supportive and palliative care into everyday oncology practice.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Enrique Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis, Yanin Chavarri‐Guerra, Alfredo Covarrubias‐Gomez, África Navarro‐Lara, Paulina Quiroz‐Friedman, Sofía Sánchez‐Román, Natasha Alcocer‐Castillejos, Juan Alberto Chávarri‐Maldonado, Paul E. Goss

Provision of study material or patients: Enrique Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis, Yanin Chavarri‐Guerra, Alfredo Covarrubias‐Gomez, África Navarro‐Lara, Paulina Quiroz‐Friedman, Sofía Sánchez‐Román, Natasha Alcocer‐Castillejos, María T. Bourlon, Roberto de la Peña‐Lopez, Héctor de la Mora‐Molina, Eucario León‐Rodriguez

Collection and/or assembly of data: Wendy Alicia Ramos‐Lopez, Jacqueline Alcalde‐Castro, José Carlos Aguilar‐Velazco, Alexandra Bukowski, Sergio Contreras‐Garduño, Lindsay Krush, Itoro Inoyo, Andrea Medina‐Campos, María Luisa Moreno‐García, Viridiana Perez‐Montessoro

Data analysis and interpretation: Enrique Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis, Yanin Chavarri‐Guerra, Alejandro Mohar, Paul E. Goss

Manuscript writing: Enrique Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis, Yanin Chavarri‐Guerra

Final approval of manuscript: Enrique Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis, Yanin Chavarri‐Guerra, Wendy Alicia Ramos‐Lopez, Jacqueline Alcalde‐Castro, Alfredo Covarrubias‐Gomez, África Navarro‐Lara, Paulina Quiroz‐Friedman, Sofía Sánchez‐Román, Natasha Alcocer‐Castillejos, José Carlos Aguilar‐Velazco, Alexandra Bukowski, Juan Alberto Chávarri‐Maldonado, Sergio Contreras‐Garduño, Lindsay Krush, Itoro Inoyo, Andrea Medina‐Campos, María Luisa Moreno‐García, Viridiana Perez‐Montessoro, María T. Bourlon, Roberto de la Peña‐Lopez, Héctor de la Mora‐Molina, Eucario León‐Rodriguez, Alejandro Mohar, Paul E. Goss

Disclosures

Enrique Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis: National System of Investigators of Mexico (RF); Yanin Chavarri‐Guerra: Roche (RF); María T. Bourlon: Tecnofarma, Asofarma, Bayer, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, Eisai, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Ipsen (H), Asofarma (ET). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the Global Cancer Institute to E.S.‐P.‐d.‐C. and Y.C.‐G. Dr. Soto‐Pérez‐de‐Celis is currently enrolled in the Doctorado en Ciencias Médicas, Odontológicas y de la Salud at Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Strengthening of palliative care as a component of integrated treatment throughout the life course. Provisional Agenda Item 9.4. EB134/28. 20 December 2013. Available at https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA67/A67_31-en.pdf. Accessed on June 5, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2. World Health Organization . National Cancer Control Programmes: Policies and managerial guidelines. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2002. Available at https://www.who.int/cancer/media/en/408.pdf. Accessed on June 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: Patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:1438–1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non–small‐cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med 2010;363:733–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fischer SM, Kline DM, Min SJ et al. Effect of Apoyo con Cariño (Support With Caring) trial of a patient navigator intervention to improve palliative care outcomes for Latino adults with advanced cancer: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol 2018;4:1736–1741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:96–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Osman H, Shrestha S, Temin S et al. Palliative care in the global setting: ASCO resource‐stratified practice guideline. J Glob Oncol 2018;4:1–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care–Creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alcalde‐Castro MJ, Soto‐Perez‐de‐Celis E, Covarrubias‐Gómez A et al. Symptom assessment and early access to supportive and palliative care for patients with advanced solid tumors in Mexico. J Palliat Care 2020;35:40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: A Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:e588–e653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bernardo BM, Zhang X, Beverly Hery CM et al. The efficacy and cost‐effectiveness of patient navigation programs across the cancer continuum: A systematic review. Cancer 2019;125:2747–2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bukowski A, Chávarri‐Guerra Y, Goss PE. The potential role of patient navigation in low‐ and middle‐income countries for patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:994–995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cella D, Hernandez L, Bonomi AE et al. Spanish language translation and initial validation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Quality‐of‐Life Instrument. Med Care 1998;36:1407–1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Arrieta J, Aguerrebere M, Raviola G et al. Validity and utility of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ)‐2 and PHQ‐9 for screening and diagnosis of depression in rural Chiapas, Mexico: A cross‐sectional study. J Clin Psychol 2017;73:1076–1090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jang RW, Caraiscos VB, Swami N et al. Simple prognostic model for patients with advanced cancer based on performance status. J Oncol Pract 2014;10:e335–e341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Badia X, Muriel C, Gracia A et al. Validation of the Spanish version of the Brief Pain Inventory in patients with oncological pain [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc) 2003;120:52–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. García‐Campayo J, Zamorano E, Ruiz MA et al. Cultural adaptation into Spanish of the generalized anxiety disorder‐7 (GAD‐7) scale as a screening tool. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2010;8:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Gort AM, Mazarico S, Ballesté J et al. Use of Zarit scale for assessment of caregiver burden in palliative care [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc) 2003;121:132–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Soubeyran P, Bellera C, Goyard J et al. Screening for vulnerability in older cancer patients: The ONCODAGE Prospective Multicenter Cohort Study. PLoS One 2014;9:e115060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ley de Voluntad Anticipada para el Distrito Federal. Mexico City Legislative Assembly (August 27, 2012) [in Spanish]. Available at http://aldf.gob.mx/archivo‐077346ece61525438e126242a37d313e.pdf. Accessed on November 26, 2020.

- 21. Cella D, Hahn EA, Dineen K. Meaningful change in cancer‐specific quality of life scores: Differences between improvement and worsening. Qual Life Res 2002;11:207–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vanbutsele G, Pardon K, Van Belle S et al. Effect of early and systematic integration of palliative care in patients with advanced cancer: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:394–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gaertner J, Siemens W, Meerpohl JJ et al. Effect of specialist palliative care services on quality of life in adults with advanced incurable illness in hospital, hospice, or community settings: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. BMJ 2017;357:j2925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Haun MW, Estel S, Rücker G et al. Early palliative care for adults with advanced cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;6:CD011129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jamie HVR, Raymond V, Alain S. Barriers and approaches to the successful integration of palliative care and oncology practice. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013;11(suppl 1):S11–S16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Peters DH, Tran NT, Adam T. Implementation Research in Health: A Practical Guide. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Rao JK, Anderson LA, Lin F‐C et al. Completion of advance directives among U.S. consumers. Am J Prev Med 2014;46:65–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Miranda F. Every year, a thousand people request advance directives. Milenio 2018. March 24. Available at https://www.milenio.com/ciencia‐y‐salud/ano‐mil‐personas‐piden‐voluntad‐anticipada. Accessed on June 5, 2020.

- 29. Instituto Nacional de Estadistica y Geografía. General Mortality. Available at https://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/olap/Proyectos/bd/continuas/mortalidad/MortalidadGeneral.asp. Accessed on June 5, 2020.

- 30. Fulton JJ, LeBlanc TW, Cutson TM et al. Integrated outpatient palliative care for patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Palliat Med 2019;33:123–134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Temel JS, Greer JA, El‐Jawahri A et al. Effects of early integrated palliative care in patients with lung and GI cancer: A randomized clinical trial. J Clin Oncol 2016;35:834–841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Azizabadi Farahani M, Assari S. Relationship between pain and quality of life In: Preedy VR, Watson RR, eds. Handbook of Disease Burdens and Quality of Life Measures. New York: Springer, 2010;3933–3953. [Google Scholar]