Abstract

Background

Depression and anxiety are common in patients with breast cancer and associated with worse quality of life and treatment outcomes. Yet, these symptoms are often underrecognized and undermanaged in oncology practice. The objective of this study was to describe depression and anxiety severity and associated patient factors during adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy in women with early breast cancer using repeated single‐item reports.

Materials and Methods

Depression and anxiety were measured from consecutive patients and their clinicians during chemotherapy infusion visits. Associations between psychiatric symptoms and patient characteristics were assessed using Fisher's exact tests for categorical variables and t tests for continuous variables. The joint relationship of covariates significant in unadjusted analyses was evaluated using log‐binomial regression. Cohen's kappa was used to assess agreement between patient‐ and clinician‐reported symptoms.

Results

In a sample of 256 patients, 26% reported at least moderately severe depression, and 41% reported at least moderately severe anxiety during chemotherapy, representing a near doubling in the prevalence of these symptoms compared with before chemotherapy. Patient‐provider agreement was fair (depression: κ = 0.31; anxiety: κ = 0.28). More severe psychiatric symptoms were associated with being unmarried, having worse function, endorsing social activity limitations, using psychotropic medications, and having a mental health provider. In multivariable analysis, social activity limitations were associated with more severe depression (relative risk [RR], 2.17; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.36–3.45) and anxiety (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.05–2.09).

Conclusion

Oncologists frequently underestimate patients’ depression and anxiety and should consider incorporating patient‐reported outcomes to enhance monitoring of mental health symptoms.

Implications for Practice

In this sample of 256 patients with breast cancer, depression and anxiety, measured using single‐item toxicity reports completed by patients and providers, were very common during adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Patient‐reported depression and anxiety of at least moderate severity were associated with multiple objective indicators of psychiatric need. Unfortunately, providers underrecognized the severity of their patients’ mental health symptoms. The use of patient‐reported, single‐item toxicity reports can be incorporated into routine oncology practice and provide clinically meaningful information regarding patients’ psychological health.

Keywords: Cancer, Breast cancer, Depression, Anxiety, Patient‐reported outcome measures

Short abstract

Depression and anxiety are underrecognized and undermanaged in oncology practice. This article describes the severity of depression and anxiety and associated factors in women with early breast cancer undergoing chemotherapy.

Introduction

Depression is experienced by 25% to 30% of women with breast cancer during their cancer care [1, 2]. Anxiety is also common in breast cancer, observed in over 20% of patients [3] and often co‐occurring with depression [4, 5, 6]. Several studies have shown that depression and anxiety may be especially severe during chemotherapy treatment [4, 5, 6, 7], possibly related to the physical symptom burden and the impact of breast cancer treatment on sexuality and fertility [6, 8, 9].

Depression and anxiety experienced during treatment are inversely correlated with overall quality of life [7, 10]. These symptoms may also decrease acceptance of, compliance with, and tolerability of chemotherapy [11, 12, 13]. This is of major importance, as the goal of adjuvant therapy is to increase the chance for cure. Especially worrisome is that both clinician‐confirmed major depression and patient‐reported depressive symptoms are known to decrease survival among adults with cancer [14].

Oncologists often underestimate the prevalence of depression experienced by their patients [15], which increases the likelihood of undermanaging their patients’ psychiatric needs [16]. Research regarding the psychological experience of patients with cancer has largely been limited to cross‐sectional studies or two time point comparisons before and after chemotherapy. The dearth of research assessing patients at multiple points during cancer treatment reveals opportunities to better understand patients’ mood and for timely interventions that might improve the likelihood of patients completing treatment [17, 18].

One way to identify symptoms that is feasible in clinical practice is the use of single‐item measures. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) is a clinician‐rated treatment tolerability measure that assesses the severity of adverse events. To capture patient perspectives on symptom severity, the NCI's Patient‐Reported Outcomes–CTCAE (PRO‐CTCAE) has been incorporated into clinical trials and clinical practice studies [19, 20], including two studies focused exclusively on women receiving chemotherapy for early breast cancer [13, 21]. The primary objective of the current study is to describe severity of depression and anxiety from the start through end of chemotherapy in patients with early breast cancer using single‐item toxicity reports completed by both patients and clinicians. As secondary aims, we evaluate patient characteristics associated with depression and anxiety, describe how these symptoms were managed in oncology practice, and examine the congruence between patient‐reported and clinician‐rated mental health symptoms.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Participants

This study provides an ancillary analysis of depression and anxiety symptoms reported by women recruited into one of three intervention studies encouraging moderate walking during chemotherapy to improve a myriad of functional, quality of life, and chemotherapy‐related toxicity outcomes (NCT02167932, NCT02328313, and NCT03761706) between April 2014 and October 2018. Trial eligibility criteria were age 21 years or older, English‐speaking, histologically confirmed stage I–III breast cancer, and scheduled for adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy. These studies were approved by the University of North Carolina–Chapel Hill Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Protocol Review Committee and institutional review boards of participating sites. Written informed consent meeting university and federal guidelines was obtained from each participant.

Measures

Patient‐ and Clinician‐Reported Depression and Anxiety

A Patient‐Reported Symptom Monitoring (PRSM) instrument [22] that inquired about symptoms “in the past 7 days” was used to monitor 17 toxicities throughout chemotherapy, including depression and anxiety. The PRSM instrument is very similar to the PRO‐CTCAE [19, 20], which was not available to the general community when the first two intervention trials were started but became available and was used in the third trial. At scheduled infusion visits throughout chemotherapy, patients rated their symptom severity as follows: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe, or 4 = very severe. During the same visit, the patients’ oncology clinicians independently completed a CTCAE form to rate depression and anxiety as follows: 0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate, 3 = severe symptoms limiting self‐care, or 4 = life‐threatening. Patient reports were not shared with their clinicians.

For regimens entailing weekly infusions, symptom report forms were completed by study participants every other week; for patients receiving triweekly regimens, these forms were completed every 3 weeks. For patients on chemotherapy/anti‐HER2 regimens whose anti‐HER2 treatment continued beyond chemotherapy, symptom reports were collected only during the chemotherapy portion of their treatment. On average, there were five patient‐clinician paired symptom reports per patient (range, 1–19).

At baseline only, participants also completed the Mental Health Index (MHI‐13), which has established subscale cut points for clinically significant depression (≥12) and anxiety (≥6) [23, 24].

Patient‐Reported Physical Function and Social Well‐Being

Prior to chemotherapy initiation, study participants also completed the patient‐reported Karnofsky Performance Status (Patient‐KPS) [25] and Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Activity Limitations and Social Support Surveys [26]. The MOS Social Activities Limitations Survey is a four‐item measure inquiring about interference with social activities due to physical or emotional health. Scores range from 0 to 100 (higher is better) with scores <50 indicating significant limitations. The MOS Social Support Survey is a 12‐item measure inquiring about the availability of someone to provide support for certain circumstances (e.g., if you are confined to a bed) or for personal support (e.g., someone who will listen to you when you need to talk) and is presented in this study as none/a little of the time vs. some/most/all of the time for Emotional and Tangible subscales.

Electronic Medical Records

Research staff abstracted information regarding breast cancer stage (according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer, version 7), phenotype, and treatment from electronic medical records. Psychiatric diagnoses, engagement in mental health specialty care, and medications for depression and anxiety were also abstracted. Diagnoses were recorded from the active problem list and past medical history sections of any notes documented during chemotherapy, and categorized as depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, adjustment disorder, bipolar disorder, substance use disorders, or other. Participants were deemed to be engaged in mental health care if they had at least one documented visit with a mental health professional (psychiatrist, psychologist, or other mental health therapist) that occurred during this phase of their cancer treatment. Medications were classified as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), benzodiazepines, or other. To avoid including benzodiazepines used sparingly for alternative indications (e.g., nausea), benzodiazepines were only included if prescribed on a scheduled basis or with the as needed indication of “anxiety.”

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the participants. Fisher's exact test was used to evaluate associations of categorical characteristics with the presence of moderate/severe/very severe patient‐reported depression and anxiety. Student's t tests were used to evaluate associations for continuous variables. Log‐binomial regression modeling was used to evaluate the joint relationship of patient characteristics significant (p < .1) in the unadjusted setting with the dichotomous outcomes of anxiety and depression. Cohen's kappa was used to evaluate agreement of patient‐reported toxicity reports with MHI subscales and clinician CTCAE scores using the following a priori cut points: 0.0 agreement totally by chance, 0.01–0.20 slight agreement, 0.21–0.40 fair agreement, 0.41–0.60 moderate agreement, 0.61–0.80 substantial agreement, and 0.81–0.99 almost perfect agreement [27]. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC), and two‐sided p < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Participants

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Our sample included 256 women with stage I–III breast cancer. Participants were mostly White (73%), and mean age was 57 years. Most had greater than a high school education (88%) and did not live alone (79%).

Table 1.

Study participant (n = 256) characteristics prior to chemotherapy initiation (baseline)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), yr | 57.2 (13.2) |

| Race | |

| White | 188 (73.4) |

| Black or African American | 52 (20.3) |

| Other | 16 (6.3) |

| Education | |

| High school or less | 30 (11.8) |

| Beyond high school | 225 (88.2) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 139 (54.7) |

| Not married | 115 (45.3) |

| Living alone | |

| Yes | 54 (21.2) |

| No | 201 (78.8) |

| Employed (hours per week) | |

| Less than 32 | 171 (67.1) |

| 32 or more | 84 (32.9) |

| Stage | |

| I | 63 (24.7) |

| II | 124 (48.6) |

| III | 68 (26.7) |

| HER2 | |

| Positive | 66 (25.8) |

| Negative | 190 (74.2) |

| Hormone receptor | |

| Positive | 154 (60.2) |

| Negative | 102 (39.8) |

| Chemotherapy regimen | |

| Anthracycline‐based | 115 (44.9) |

| Taxane‐based | 110 (43.0) |

| Other | 31 (12.1) |

| Patient Karnofsky performance status (higher score signifies better function) | |

| Less than 80 | 18 (7.2) |

| 80 or higher | 231 (92.8) |

| Social Activity Limitations (range, 0–100; higher score signifies greater activity/fewer limitations) | |

| Less than 50 | 35 (16.3) |

| 50 or higher | 180 (83.7) |

| Social support—emotional (“do you have someone…”) | |

| None/a little of the time | 8 (3.8) |

| Some/most/all of the time | 203 (96.2) |

| Social support—tangible (“do you have someone…”) | |

| None/a little of the time | 13 (6.1) |

| Some/most/all of the time | 199 (93.9) |

| Medications | |

| Any | 104 (42.1) |

| SSRI | 41 (16.6) |

| SNRI | 7 (2.8) |

| Benzodiazepine | 63 (25.5) |

| Other antidepressant or anxiolytic | 24 (9.7) |

| Mental Health Index—Depression (range, 0–43; cut point for depression is score ≥12) | |

| Less than 12 | 179 (75.2) |

| 12 or higher | 59 (24.8) |

| Mental Health Index—Anxiety (range, 0–20; cut point for anxiety is score ≥6) | |

| Less than 6 | 142 (57.5) |

| 6 or higher | 105 (42.5) |

| Patient‐reported symptom—depression | |

| None | 136 (53.3) |

| Mild | 89 (34.9) |

| Moderate | 24 (9.4) |

| Severe | 5 (2.0) |

| Very severe | 1 (0.4) |

| Patient‐reported symptom—anxiety | |

| None | 92 (35.9) |

| Mild | 109 (42.6) |

| Moderate | 44 (17.2) |

| Severe | 9 (3.5) |

| Very severe | 2 (0.8) |

| Clinician‐assessed symptom—depression | |

| None (grade 0) | 137 (82.5) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 23 (13.9) |

| Moderate (grade 2) | 4 (2.4) |

| Severe (grade 3) | 2 (1.2) |

| Clinician‐assessed symptom—anxiety | |

| None (grade 0) | 87 (52.4) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 62 (37.3) |

| Moderate (grade 2) | 15 (9.0) |

| Severe (grade 3) | 2 (1.2) |

Abbreviations: SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Patient‐Reported and Clinician‐Rated Depression and Anxiety

Prior to chemotherapy, 12% of participants reported moderate, severe, or very severe depression and 21% reported at least moderately severe anxiety (Table 1). However, using established MHI cut points for clinical diagnosis, both depression and anxiety were almost twice as prevalent prior to chemotherapy. Agreement between the single‐item patient reports and MHI was fair (depression: κ = 0.38, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.24–0.51; anxiety: κ = 0.33, 95% CI, 0.22–0.43).

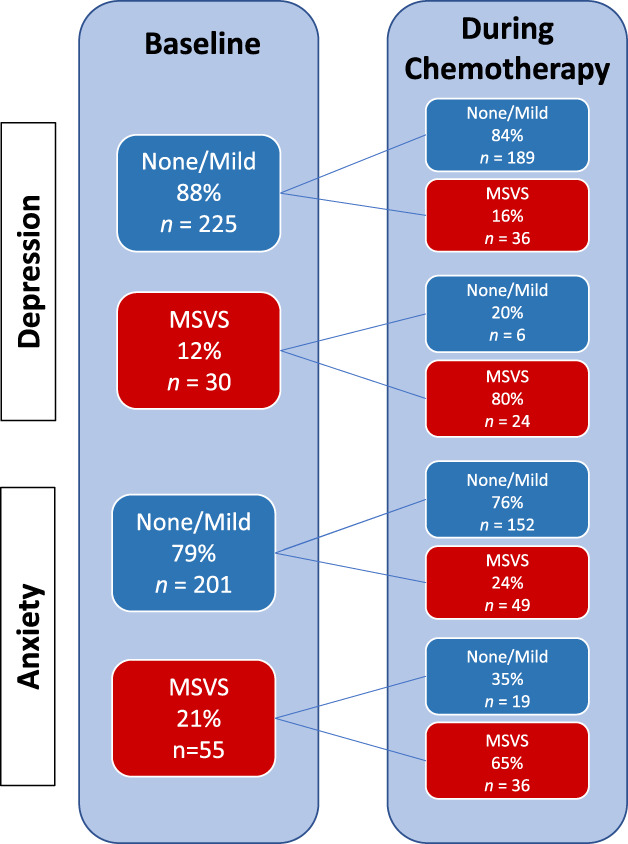

When patients were examined serially throughout treatment, the cumulative incidence of patient‐reported moderate, severe, or very severe depressive symptoms increased to 26% (Table 2). Eighty percent of participants who endorsed at least moderately severe depression at baseline continued to report high intensity symptoms during chemotherapy (Fig. 1). Of interest, 16% (n = 36) of patients who reported no or only mild symptoms of depression at baseline developed moderate, severe, or very severe depressive symptoms during treatment. By comparison, anxiety symptoms were more common, with 41% rating anxiety at least moderately severe at some point during chemotherapy and varied more over the treatment course. For example, 24% of patients who reported no or mild anxiety symptoms at baseline developed moderate, severe, or very severe anxiety during treatment. Alternatively, 35% of patients who described at least moderately severe anxiety symptoms at baseline reported either mild or no symptoms of anxiety at all subsequent time points during treatment.

Table 2.

Depression and anxiety characteristics and management during treatment (after baseline)

| Variable | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Psychiatric diagnosis a | |

| Any psychiatric diagnosis | 96 (37.5) |

| Depression | 53 (20.7) |

| Anxiety | 42 (16.4) |

| Adjustment disorder | 5 (2.0) |

| Bipolar disorder | 4 (1.6) |

| Substance use disorder | 5 (2.0) |

| Other | 10 (3.9) |

| Mental health specialty care a | 43 (18.1) |

| Medications added a | |

| Any medications | 40 (16.8) |

| SSRI | 9 (3.8) |

| SNRI | 10 (4.2) |

| Benzodiazepine | 25 (10.5) |

| Other antidepressant or anxiolytic | 6 (2.5) |

| Baseline medication dose increased during treatment a | 6 (6.5) |

| Patient‐reported symptom—depression b | |

| None | 72 (28.1) |

| Mild | 117 (45.7) |

| Moderate | 56 (21.9) |

| Severe | 7 (2.7) |

| Very severe | 4 (1.6) |

| Patient‐reported symptom—anxiety b | |

| None | 58 (22.7) |

| Mild | 94 (36.7) |

| Moderate | 81 (31.6) |

| Severe | 18 (7.0) |

| Very severe | 5 (2.0) |

| Clinician‐assessed symptom—depression b | |

| None (grade 0) | 133 (56.8) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 72 (30.8) |

| Moderate (grade 2) | 21 (9.0) |

| Severe (grade 3) | 8 (3.4) |

| Clinician‐assessed symptom—anxiety b | |

| None (grade 0) | 61 (26.1) |

| Mild (grade 1) | 125 (53.4) |

| Moderate (grade 2) | 41 (17.5) |

| Severe (grade 3) | 7 (3.0) |

Extracted from the electronic medical record.

Highest severity at any point during treatment.

Abbreviations: SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Figure 1.

Changes in patient‐reported depression and anxiety severity from prechemotherapy to during chemotherapy.Abbreviation: MSVS, moderate, severe, or very severe.

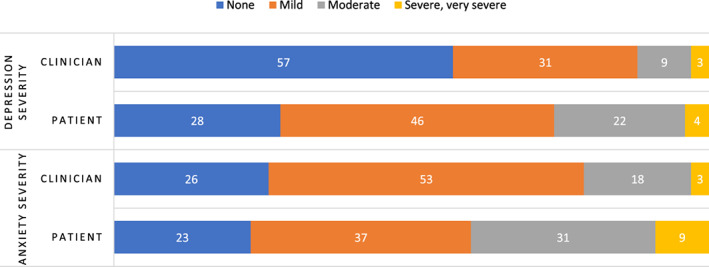

Clinician toxicity reports were available for 234 of the 256 participants. At baseline, clinicians rated 4% of their patients as having moderate or higher depression and 10% as having moderate or higher anxiety (Table 1). Longitudinally, clinician‐rated depression rose to 12%, and anxiety rose to 21% (Table 2). Agreement between clinician and patient reports were fair (depression: weighted κ = 0.31, 95% CI, 0.23–0.39; anxiety: weighted κ = 0.28, 95% CI, 0.20–0.36). Figure 2 compares highest symptom scores at any time during chemotherapy between patients and their clinicians.

Figure 2.

Comparison between highest patient‐reported and clinician‐assessed depression and anxiety during chemotherapy, shown as a percentage.

Association of Patient and Clinical Characteristics with Depression and Anxiety

Patient‐reported moderate, severe, or very severe anxiety during chemotherapy was significantly associated with being unmarried (p = .021), having lower Patient‐KPS (p = .023), and having more limitations in social activities (p = .003). Similarly, moderate or higher patient‐reported depression during chemotherapy was associated with being unmarried (p = .010), employed less than full time (p = .035), lower Patient‐KPS (p = .021), and more social activity limitations (p < .001). In multivariable analyses, only limitations in social activities remained significantly associated with more severe depression (relative risk [RR], 2.17; 95% CI, 1.36–3.45) and anxiety (RR, 1.48; 95% CI, 1.05–2.09).

Mental Health Care During Treatment

Twenty‐one percent of participants had depressive disorders and 16% had anxiety disorders documented in their electronic medical records at any time during chemotherapy (Table 2). Close to 20% were engaged with a mental health provider during chemotherapy. At the start of treatment, 42% were receiving psychiatric medications. Benzodiazepines were the most common, even after excluding those indicated for nausea, vomiting, and insomnia. Six percent of participants taking a psychiatric medication at baseline had the dose increased during chemotherapy, and 17% of all participants had new psychiatric medications added.

Psychiatric diagnoses were strongly associated with moderate or higher patient‐reported anxiety and depression during chemotherapy (Table 3). For anxiety, these associations were significant for individual medications noted in the electronic health record at baseline (SSRIs p = .04, SNRIs p = .02, benzodiazepines p = .001), psychiatric diagnoses noted in the electronic medical record (depression p < .001, anxiety p < .001), and interactions with a mental health specialist (p < .0001). For depression, associations were significant for SNRIs added during treatment (p = .025), psychiatric diagnoses (depression p < .0001, anxiety p = .001), and interactions with a mental health specialist (p < .0001).

Table 3.

Association of pretreatment patient and clinical characteristics with patient‐reported moderate, severe, or very severe depression and anxiety during treatment

| Anxiety | Depression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n (%) | p value | n (%) | p value |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 57.4 (13.7) | .811 | 58.6 (13.2) | .312 |

| Race | 0.668 | .748 | ||

| White | 41.5 | 25.5 | ||

| Non‐White | 38.2 | 27.9 | ||

| Education | .167 | .187 | ||

| High school or less | 53.3 | 36.7 | ||

| More than high school | 39.1 | 24.9 | ||

| Marital status | .021 | .010 | ||

| Married | 33.8 | 19.4 | ||

| Unmarried | 48.7 | 33.9 | ||

| Living alone | .876 | .862 | ||

| Yes | 38.9 | 27.8 | ||

| No | 41.3 | 25.9 | ||

| Employment (hours/week) | .058 | .035 | ||

| Less than 32 | 45.0 | 30.4 | ||

| 32 or more | 32.1 | 17.9 | ||

| Stage | .212 | .395 | ||

| I | 31.8 | 25.4 | ||

| II | 45.2 | 23.4 | ||

| III | 41.2 | 32.4 | ||

| Chemotherapy regimen | .798 | .317 | ||

| Anthracycline‐based | 41.7 | 29.6 | ||

| Not anthracycline‐based | 39.7 | 23.4 | ||

| Patient Karnofsky performance status | .023 | .021 | ||

| Less than 80 | 66.7 | 50.0 | ||

| 80 or higher | 37.7 | 23.4 | ||

| Social Activity Limitations score | .003 a | <.001 a | ||

| Less than 50 (greater limitations) | 68.6 | 57.1 | ||

| 50 or higher (fewer limitations) | 39.4 | 23.3 | ||

| Social support—emotional | .147 | .689 | ||

| None/little | 75.0 | 37.5 | ||

| Some/most/all | 43.8 | 27.6 | ||

| Social support—tangible | .253 | .197 | ||

| None/little | 61.5 | 46.2 | ||

| Some/most/all | 43.2 | 26.6 | ||

| Medications | .001 | .190 | ||

| Any | 53.9 | 30.8 | ||

| None | 31.5 | 23.1 | ||

| SSRI b | .037 | .244 | ||

| Yes | 56.1 | 34.2 | ||

| No | 37.9 | 24.7 | ||

| SNRI b | .020 | .080 | ||

| Yes | 85.7 | 57.1 | ||

| No | 39.6 | 25.4 | ||

| Benzodiazepine b | .001 | .413 | ||

| Yes | 34.8 | 30.2 | ||

| No | 58.7 | 25.0 | ||

| Other b | .829 | .223 | ||

| Yes | 37.5 | 37.5 | ||

| No | 41.3 | 25.1 | ||

| Baseline medication dose increased c | .232 | .397 | ||

| Yes | 83.3 | 50.0 | ||

| No | 55.2 | 32.2 | ||

| Medications added c | .292 | .435 | ||

| Any | 50.0 | 32.5 | ||

| None | 39.9 | 25.8 | ||

| SSRI | .496 | .705 | ||

| Yes | 55.6 | 33.3 | ||

| No | 41.1 | 26.6 | ||

| SNRI | .327 | .025 | ||

| Yes | 60.0 | 60.0 | ||

| No | 40.8 | 25.4 | ||

| Benzodiazepine | .289 | .634 | ||

| Yes | 52.0 | 32.0 | ||

| No | 40.4 | 26.3 | ||

| Other antidepressant or anxiolytic | .695 | 0.999 | ||

| Yes | 50.0 | 16.7 | ||

| No | 41.4 | 27.2 | ||

| Psychiatric diagnosis c | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Any | 55.2 | 41.7 | ||

| None | 31.9 | 16.9 | ||

| Depression | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Yes | 66.0 | 50.9 | ||

| No | 34.0 | 19.7 | ||

| Anxiety | <.001 | .001 | ||

| Yes | 66.7 | 47.6 | ||

| No | 35.5 | 22.0 | ||

| Adjustment disorder | .162 | .608 | ||

| Yes | 39.8 | 40.0 | ||

| No | 80.0 | 25.9 | ||

| Bipolar disorder | 0.999 | 0.999 | ||

| Yes | 50.0 | 25.0 | ||

| No | 40.5 | 26.2 | ||

| Substance use disorder | .399 | 0.999 | ||

| Yes | 60.0 | 20.0 | ||

| No | 40.2 | 26.3 | ||

| Other | .208 | .294 | ||

| Yes | 20.0 | 40.0 | ||

| No | 41.5 | 25.6 | ||

| Mental health specialty care c | <.001 | <.0001 | ||

| Yes | 74.4 | 58.1 | ||

| No | 34.5 | 20.1 | ||

p < .05 after adjustment for marital status, employment, performance status, and social activity limitations.

Compares those who did and did not receive medications in the entire study population (not exclusive to the subset receiving psychotropic medications).

Medications, psychiatric diagnoses, and mental health care were evaluated over the entire treatment period. All other associations were with variables measured at baseline.

Abbreviations: SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

Discussion

In our cohort of women receiving chemotherapy for early breast cancer, depression and anxiety were highly prevalent. The during‐treatment prevalence of patient‐reported anxiety or depression almost doubled from prechemotherapy levels, with over 25% reporting at least moderately severe depression and over 40% reporting at least moderately severe anxiety during chemotherapy. By comparison, clinician reporting of their patients’ depression and anxiety during treatment more than doubled from baseline with peak prevalences of 12% (depression) and 21% (anxiety). However, this still only captured half of the patients reporting at least moderately severe symptoms.

Disagreement between patient‐reported and clinician‐rated cancer treatment–related side effects is well documented [28, 29]. Providers tend to report lower severity of toxic effects, especially for symptoms that are not clearly evident by physical exam [30]. Our study similarly found only fair agreement between the patient‐reported and clinician‐rated symptoms. We also found only fair agreement between single‐item patient reports and the MHI‐13 [24]. Specifically, the proportion of women with MHI‐defined clinically significant anxiety or depression was twice what was identified using a threshold of moderate or greater severity on the single‐item reports. Although this may suggest greater sensitivity of the MHI‐13 compared with the PRSM instrument or PRO‐CTCAE, it may also suggest that the single‐item measures are more specific for these mental health symptoms. Future studies are needed to clarify the reasons underlying these differences.

The strongest and most consistent association with depression and anxiety during treatment was with limitations in social activities. Decreased social functioning has been identified as predictive of depression and anxiety symptoms in patients with cancer [31, 32]. Of interest, interventions aimed at improving social activity, such as behavioral activation therapy, which emphasizes systematically increasing the number of activities consistent with a person's values and goals, may be one effective way to target psychological distress [33]. In our sample, being married and having good functional status also may have mitigated during‐treatment depression and anxiety. These relationships are intuitive, as a spouse can offer a unique source of psychosocial support and greater physical function may enhance resiliency to the toxicity of chemotherapy [17, 34].

Importantly, patient‐reported symptom scores were associated with multiple other measures of psychiatric symptomatology, including established clinical diagnoses, psychotropic medication use, and engagement in mental health care. Nineteen percent of patients were under the care of a mental health professional during chemotherapy treatment. This degree of engagement far exceeds what has been reported previously. Specifically, in a cross‐sectional study of over 20,000 patients with cancer seen in ambulatory care settings, only 5% meeting criteria for major depression received care with a mental health professional [16]. The comanagement of psychiatric symptoms with mental health providers in our study is particularly remarkable when considering that the patient psychiatric symptom reports were not given to the providers in our study. We suspect that the presence of an embedded comprehensive cancer support program, which provides an infrastructure for patients to receive mental health care at our cancer center and often on an “on demand” basis, facilitated patient usage of mental health resources.

Many participants received psychiatric medications during chemotherapy. Benzodiazepines were the most commonly prescribed medications. Although we excluded psychotropic medications explicitly indicated for nonpsychiatric symptoms (e.g., lorazepam for chemotherapy‐induced nausea), we suspect that there were patients prescribed benzodiazepines without a clear indication, or where the documented indication was anxiety but who were instructed to use only if needed, which may have overrepresented the number of patients actually needing or using these medications. Given the risk for dependence, falls, negative cognitive outcomes, and respiratory depression associated with benzodiazepines, it would be concerning if approximately one third of all patients in our study were actually taking these medications. However, it may also be justifiable in the setting of active cancer treatment and the absence of effective, short‐acting alternatives. Specifically, SSRIs and evidence‐based psychotherapies require several weeks to generate a desired response, and other medications may have their own adverse side effects (e.g., metabolic syndrome with atypical antipsychotics). Despite psychiatric symptoms being common and worsening during chemotherapy, it was relatively uncommon for providers to add psychiatric medications during chemotherapy and even less common to adjust the dosage. This further emphasizes the importance of referral to mental health providers, particularly for patients with more severe or complex psychological needs.

Our study has some limitations. Although our study population was diverse in terms of race (26% non‐White) and breast cancer subtypes, the overall sample was highly educated and reported a high degree of social support. Also, although our primary outcomes were assessed prospectively and through direct patient and clinician report, the psychiatric variables ascertained by electronic medical chart review may underestimate the true levels of these variables. Specifically, patients may have underreported psychiatric diagnoses or care under a mental health provider. And, even if a treating oncology provider was aware, it may not have been documented in the clinician notes if it was not considered immediately relevant to the oncologic care of their patient. The higher proportion of patients in our study receiving psychotropic medications relative to those with psychiatric diagnoses supports this possibility. A related issue is that although we believe the medical record provided accurate information about what was prescribed, patient compliance could not be ascertained. Finally, although we compared the patient‐reported and CTCAE scores with the MHI depression and anxiety subscales prior to chemotherapy, our study would have been strengthened by comparison between the single‐item toxicity reports to the MHI or other validated instruments at additional time points during treatment.

Conclusion

Our study has several important clinical implications. We observed a substantial increase in patient‐reported depression and anxiety symptoms during cancer treatment and identified patient characteristics associated with these mental health symptoms, including social activity limitations, poor functional status, and being unmarried, emphasizing populations requiring closer mental health surveillance during cancer treatment. Although patient‐reported, single‐item measures have demonstrated good reliability and validity for evaluating psychological distress [35] and overall well‐being [36] in patients with cancer, less is known about the use of these measures for depression and anxiety specifically. Although the goal of this study was not to validate single‐item reports of depression and anxiety against a gold standard, we believe that their association with established diagnoses of depression or anxiety, psychiatric medication use, and engagement in mental health subspecialty care, combined with their brevity and established feasibility [19, 37], highlight the potential value of incorporating the PRSM instrument, PRO‐CTCAE, or similar single‐item measures into routine oncology practice to enhance standard of care monitoring of depression and anxiety by clinicians. Future research will investigate the utility of using brief patient‐reported outcomes for mental health at end of treatment to predict psychiatric needs into survivorship.

Author Contributions

Conception/design: Zev M. Nakamura, Allison M. Deal, Kirsten A. Nyrop, Hyman B. Muss

Provision of study material or patients: Hyman B. Muss

Collection and/or assembly of data: Zev M. Nakamura, Kirsten A. Nyrop, Laura J. Quillen, Tucker Brenizer, Hyman B. Muss

Data analysis and interpretation: Allison M. Deal, Yi Tang Chen

Manuscript writing: Zev M. Nakamura, Allison M. Deal, Kirsten A. Nyrop, Hyman B. Muss

Final approval of manuscript: Zev M. Nakamura, Allison M. Deal, Kirsten A. Nyrop, Yi Tang Chen, Laura J. Quillen, Tucker Brenizer, Hyman B. Muss

Disclosures

The authors indicated no financial relationships.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Breast Cancer Research Foundation (New York, NY; Principal Investigator: H.B.M.), the Kay Yow Foundation (Raleigh, NC; Principal Investigator: H.B.M.), and the National Institutes of Health (grant number K12HD001441; scholar: Z.M.N.).

Disclosures of potential conflicts of interest may be found at the end of this article.

No part of this article may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form or for any means without the prior permission in writing from the copyright holder. For information on purchasing reprints contact Commercialreprints@wiley.com. For permission information contact permissions@wiley.com.

Footnotes

For Further Reading: Nathalie LeVasseur, Huaqi Li, Winson Cheung et al. Effects of High Anxiety Scores on Surgical and Overall Treatment Plan in Patients with Breast Cancer Treated with Neoadjuvant Therapy. The Oncologist 2020;25:212–217.

Implications for Practice: The prevalence of anxiety among women with newly diagnosed breast cancer is being increasingly acknowledged. However, health care providers have not fully appreciated the impact of anxiety on the surgical management of patients with early‐stage breast cancer. This study highlights the importance of self‐reported anxiety on surgical management. The preoperative period provides a unique window of opportunity to address sources of anxiety and provide targeted educational materials over a period of 4–6 months, which may ultimately lead to less aggressive surgery when it is not needed.

References

- 1. Deshields T, Tibbs T, Fan MY et al. Differences in patterns of depression after treatment for breast cancer. Psychooncology 2006;15:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ganz PA, Kwan L, Stanton AL et al. Quality of life at the end of primary treatment of breast cancer: First results from the moving beyond cancer randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst 2004;96:376–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Linden W, Vodermaier A, MacKenzie R et al. Anxiety and depression after cancer diagnosis: Prevalence rates by cancer type, gender, and age. J Affect Disord 2012;141:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. So WKW, Marsh G, Ling WM et al. Anxiety, depression and quality of life among Chinese breast cancer patients during adjuvant therapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2010;14:17–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vahdaninia M, Omidvari S, Montazeri A. What do predict anxiety and depression in breast cancer patients? A follow‐up study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:355–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Reece JC, Chan YF, Herbert J et al. Course of depression, mental health service utilization and treatment preferences in women receiving chemotherapy for breast cancer. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2013;35:376–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zhang J, Zhou Y, Feng Z et al. Longitudinal trends in anxiety, depression, and quality of life during different intermittent periods of adjuvant breast cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Nurs 2018;41:62–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bergerot CD, Mitchell HR, Ashing KT et al. A prospective study of changes in anxiety, depression, and problems in living during chemotherapy treatments: Effects of age and gender. Support Care Cancer 2017;25:1897–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Couzi RJ, Helzlsouer KJ, Fetting JH. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms among women with a history of breast cancer and attitudes toward estrogen replacement therapy. J Clin Oncol 1995;13:2737–2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S et al. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: Five year observational cohort study. BMJ 2005;330:702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Colleoni M, Mandala M, Peruzzotti G et al. Depression and degree of acceptance of adjuvant cytotoxic drugs. Lancet 2000;356:1326–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Badger TA, Braden CJ, Mishel MH. Depression burden, self‐help interventions, and side effect experience in women receiving treatment for breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum 2001;28:567–574. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nyrop KA, Deal AM, Shachar SS et al. Patient‐reported toxicities during chemotherapy regimens in current clinical practice for early breast cancer. The Oncologist 2019;24:762–771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Satin JR, Linden W, Phillips MJ. Depression as a predictor of disease progression and mortality in cancer patients: A meta‐analysis. Cancer 2009;115:5349–5361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fann JR, Thomas‐Rich AM, Katon WJ et al. Major depression after breast cancer: A review of epidemiology and treatment. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2008;30:112–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Walker J, Hansen CH, Martin P et al. Prevalence, associations, and adequacy of treatment of major depression in patients with cancer: A cross‐sectional analysis of routinely collected clinical data. Lancet Psychiatry 2014;1:343–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Donovan KA, Gonzalez BD, Small BJ et al. Depressive symptom trajectories during and after adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Ann Behav Med 2014;47:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hewitt M, Herdman R, Holland J, eds. Meeting Psychological Needs of Women with Breast Cancer. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Basch E, Reeve BB, Mitchell SA et al. Development of the National Cancer Institute's patient‐reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO‐CTCAE). J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Dueck AC, Mendoza TR, Mitchell SA et al. Validity and reliability of the US National Cancer Institute's patient‐reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO‐CTCAE). JAMA Oncol 2015;1:1051–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Montemurro F, Mittica G, Cagnazzo C et al. Self‐evaluation of adjuvant chemotherapy‐related adverse effects by patients with breast cancer. JAMA Oncol 2016;2:445–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Reeve BB, Mitchell SA, Dueck AC et al. Recommended patient‐reported core set of symptoms to measure in adult cancer treatment trials. J Natl Cancer Inst 2014;106:dju129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Stewart A, Ware J, eds. Measuring Functioning and Well‐Being: The Medical Outcomes Study Approach. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pergolotti M, Langer MM, Deal AM et al. Mental status evaluation in older adults with cancer: Development of the Mental Health Index‐13. J Geriatr Oncol 2019;10:241–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Loprinzi CL, Laurie JA, Wieand HS et al. Prospective evaluation of prognostic variables from patient‐completed questionnaires. North Central Cancer Treatment Group. J Clin Oncol 1994;12:601–607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Soc Sci Med 1991;32:705–714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Altman D. Practical Statistics for Medical Research. London: Chapman and Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xiao C, Polomano R, Bruner DW. Comparison between patient‐reported and clinician‐observed symptoms in oncology. Cancer Nurs 2013;36:E1–E16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nyrop KA, Deal AM, Reeder‐Hayes KE et al. Patient‐reported and clinician‐reported chemotherapy‐induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with early breast cancer: Current clinical practice. Cancer 2019;125:2945–2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Falchook AD, Green R, Knowles ME et al. Comparison of patient‐ and practitioner‐reported toxic effects associated with chemoradiotherapy for head and neck cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2016;142:517–523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gonzalez‐Saenz de Tejada M, Bilbao A, Baré M et al. Association between social support, functional status, and change in health‐related quality of life and changes in anxiety and depression in colorectal cancer patients. Psychooncology 2017;26:1263–1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gray NM, Hall SJ, Browne S et al. Predictors of anxiety and depression in people with colorectal cancer. Support Care Cancer 2014;22:307–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hopko DR, Lejuez CW, Ryba MM et al. Support for the efficacy of behavioural activation in treating anxiety in breast cancer patients. Clin Psychol 2016;20:17–26. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cantarero‐Villanueva I, Fernández‐Lao C, Fernández‐De‐Las‐Peñas C et al. Associations among musculoskeletal impairments, depression, body image and fatigue in breast cancer survivors within the first year after treatment. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2011;20:632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jacobsen PB, Donovan KA, Trask PC et al. Screening for psychologic distress in ambulatory cancer patients: A multicenter evaluation of the distress thermometer. Cancer 2005;103:1494–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. De Boer AGEM, Van Lanschot JJB, Stalmeier PFM et al. Is a single‐item visual analogue scale as valid, reliable and responsive as multi‐item scales in measuring quality of life? Qual Life Res 2004;13:311–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stover A, Irwin DE, Chen RC et al. Integrating patient‐reported measures into routine cancer care: Cancer patients’ and clinicians’ perceptions of acceptability and value. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2015;3:1169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]