Abstract

Background/Aims

The efficacy and safety of vedolizumab in moderate-to-severely active Crohn’s disease (CD) were demonstrated in the GEMINI 2 study (NCT00783692). This post-hoc exploratory analysis aimed to assess the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab in the subgroup of patients from Asian countries.

Methods

During the induction phase (doses at day 1, 15), clinical remission, enhanced clinical response, and change in C-reactive protein at 6 weeks; during the maintenance phase, clinical remission, enhanced clinical response, glucocorticoid-free remission and durable clinical remission at 52 weeks, were the efficacy outcomes of interest. Efficacy and safety of vedolizumab compared to placebo were assessed in Asian countries (Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan) using descriptive analyses.

Results

During the induction phase, in Asian countries (n = 51), 14.7% of the vedolizumab-treated patients achieved clinical remission at week 6 compared to none with placebo (difference, 14.7%; 95% confidence interval, 15.8%–43.5%). In non-Asian countries (n = 317), the remission rate at week 6 with vedolizumab was 14.5%. During maintenance, in Asian countries, clinical remission rates at 52 weeks with vedolizumab administered every 4 weeks, vedolizumab administered every 8 weeks and placebo were 41.7%, 36.4%, and 0%, respectively; while enhanced clinical response rates were 41.7%, 63.6%, and 42.9%, respectively. During induction, 39.7% of patients with vedolizumab experienced an adverse event compared to 58.8% of patients with placebo, and vedolizumab was generally well-tolerated.

Conclusions

This post-hoc analysis demonstrates the treatment effect and safety of vedolizumab in moderate-to-severely active CD in patients from Asian countries.

Keywords: Vedolizumab, Crohn disease, Asia, Remission, Maintenance

INTRODUCTION

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which include Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are chronic relapsing inflammatory disorders. The phenotype of IBD in Asia appears distinct from that in the West with notable differences in epidemiology, genetics and clinical characteristics [1-6]. Moreover, the high prevalence of infectious diseases, including tuberculosis (TB), is a concern both for diagnosis and management of IBD in Asia [7]. In Asia, the reported prevalence of CD is lower than in Western countries but has increased considerably over the recent few decades [1]. In a population-based study in South Korea, the incidence of CD increased from 0.05 per 100,000 person-years in 1986–1990 to 1.34 per 100,000 person-years in 2001–2005 [8]. A recent study reported the annual incidence of CD in 2012–2013 to be 0.34, 0.36 and 3.91 per 100,000 in Southeast Asia, East Asia and India, respectively [9]. The exact cause for the dramatic rise in incidence and prevalence of CD in Asia is unknown, though environmental factors such as changes in diet, urbanization, and improved hygiene are postulated to play a significant role [10]. Other differences include a higher prevalence in males, diagnosis at a slightly older age, less frequent positive family history and less frequent extraintestinal manifestations in Asian CD patients compared to those in the West [4-6].

Biologics, including anti-tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents, anti-integrins and anti-IL12/23 agents, constitute an important treatment option for moderate-to-severely active CD. With the rising incidence of CD, the use of biologics has also increased [11]. Important issues with the use of anti-TNF agents are the high rates of primary and secondary nonresponse [12] and the risk of opportunistic infections, including TB [11].

Vedolizumab, which is a gut-selective alpha4beta7 integrin antagonist, is promising in this regard. It has been approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severely active CD after failure with conventional therapy or anti-TNF agents. In the GEMINI 2 study [13,14], vedolizumab was significantly superior to placebo in inducing remission at 6 weeks and maintaining it at 52 weeks in patients with moderate-to-severely active CD. Vedolizumab has shown effectiveness in IBD in real-world clinical practice [15]. Clinical trial and real-world data suggest that the mechanism of action of vedolizumab may translate into a lower risk of opportunistic infections compared to anti-TNF agents [16-19].

Data on CD from Asian countries are relatively limited as most clinical trials and registry studies in CD report data from Western countries. There is a need for Asia-specific data given the role that genetic and environmental factors play in CD [20-22].

In this post-hoc exploratory analysis, the data from the Asian subgroup of the GEMINI 2 study were examined to determine the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab in patients from Asian countries with CD.

METHODS

GEMINI 2 was a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in patients with moderate-to-severely active CD. Patients from 6 Asian countries (Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, Singapore, South Korea, and Taiwan) participated in this global study, which also involved patients from 33 non-Asian countries (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Latvia, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom, and United States). The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each participating center. All patients gave written informed consent. The study methodology has been previously reported [14], and only the key elements will be summarized here.

1. Eligibility Criteria

The GEMINI 2 study involved patients with moderate-to-severely active CD with a score of 220 to 450 on the Crohn’s Disease Activity Index (CDAI). Adult patients who showed no response or experienced tolerability issues with prior treatments such as glucocorticoids, immunomodulators or TNF antagonists were eligible. Those with prior treatment with vedolizumab, natalizumab, efalizumab, or rituximab were excluded.

2. Induction Phase (till Week 6)

The induction phase involved 2 cohorts, one double-blind cohort (cohort 1) and an open-label cohort (cohort 2). In cohort 1, patients were randomized in a 3:2 ratio to double-blind treatment with intravenous vedolizumab 300 mg or placebo at weeks 0 and 2. These patients constituted the induction intent-to-treat (ITT) population. Additional patients were recruited in cohort 2, in which all patients received vedolizumab 300 mg at weeks 0 and 2 in an open-label therapy. Cohort 1 and cohort 2 patients together constituted the safety population for the induction phase. Clinical response with vedolizumab ( ≥ 70-point decrease in the CDAI score) was evaluated at the end of 6 weeks of induction treatment.

3. Maintenance Phase (Week 6 till Week 52)

Patients with clinical response to vedolizumab at week 6 were randomized in a 1:1:1 ratio to double-blind maintenance treatment with vedolizumab every 8 weeks (q8w), vedolizumab every 4 weeks (q4w), or placebo for up to 52 weeks. These patients constituted the maintenance ITT population.

Patients without clinical response to vedolizumab at 6 weeks received open-label treatment with vedolizumab 300 mg q4w, while those who received placebo during induction continued to receive placebo till week 52. Both these groups of patients (open-label vedolizumab during maintenance and placebo in induction+maintenance), along with the maintenance ITT population, constituted the safety population for the maintenance phase.

4. Outcomes

During the induction phase, the primary outcomes were clinical remission (CDAI score of ≤ 150 points) and enhanced clinical response ( ≥ 100-point decrease in the CDAI score) at week 6. The secondary induction phase outcome was the mean change in C-reactive protein (CRP) from baseline to week 6. During the maintenance phase, the primary outcome was clinical remission at week 52. Secondary maintenance phase outcomes were enhanced clinical response, glucocorticoidfree remission in patients receiving glucocorticoids at baseline (patients using oral glucocorticoids at baseline who have discontinued glucocorticoids and are in clinical remission at week 52), and durable clinical remission (clinical remission at ≥ 80% of study visits, including the final visit) at week 52.

5. Statistical Analysis

Efficacy endpoints of the induction phase (clinical remission, enhanced clinical response and change in CRP at week 6) were summarized for the Induction ITT population (patients randomized to either vedolizumab [ = cohort 1] or placebo for induction); efficacy endpoints of the maintenance phase (clinical remission at week 52, enhanced clinical remission and durable clinical remission at week 52, and glucocorticoid-free remission at week 52) were summarized for the maintenance ITT population (patients treated with vedolizumab in induction and with response at week 6, randomized to vedolizumab q4w, vedolizumab q8w or placebo for maintenance). Safety data (incidence of adverse events) was summarized for the induction and maintenance safety populations (including also patients treated with open-label vedolizumab in the respective phase).

Demographic and baseline characteristics were summarized using descriptive statistics. Efficacy endpoints were summarized descriptively (number and percentage of patients achieving outcome) by randomized treatment for the induction and maintenance phase; additionally, differences in rates between vedolizumab and placebo and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) (using normal approximation; exact method used if counts were less than or equal to 5) for these differences were provided. In view of the small numbers of subjects and post-hoc nature of the analysis, no formal statistical comparison was conducted.

All summaries were provided for patients in the Asian countries and for patients in the non-Asian countries.

RESULTS

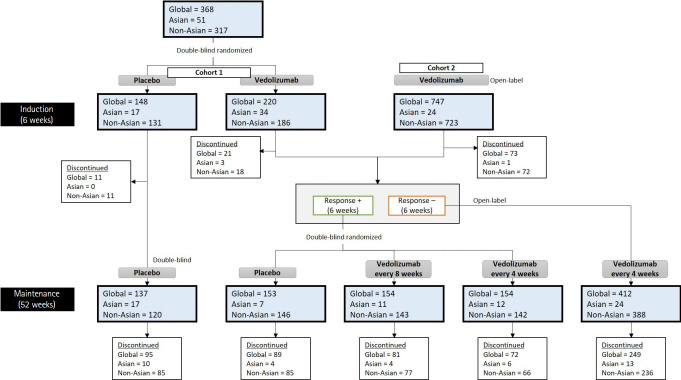

The flow of patients in the induction and maintenance phase, with the number of patients in the GEMINI 2 study, in the Asian countries, and in the non-Asian countries are shown in Fig. 1. In the GEMINI 2 study, 368 patients in the ITT induction population were enrolled with 220 patients randomized to vedolizumab and 148 to placebo (cohort 1), and 747 patients received open-label vedolizumab (cohort 2). Four hundred and sixtyone patients showed clinical response in induction on vedolizumab at week 6 and were included in the ITT maintenance population, along with 137 patients on placebo.

Fig. 1.

GEMINI 2 study schematic with number of patients in each treatment arm. During the induction phase, the Asian subgroup included 34 patients randomized to vedolizumab (cohort 1) and 17 to placebo; 24 patients received open-label vedolizumab. During the maintenance phase, in the Asian subgroup, 7 patients were randomized to placebo and 23 patients to the vedolizumab groups.

1. Asian Countries Subgroup

1) Disposition

The disposition of the Asian subgroup of the GEMINI 2 study is shown in Fig. 1. Cohort 1 consisted of 51 patients, of whom 34 were randomized to vedolizumab and 17 to placebo during induction (induction ITT population). Cohort 2 consisted of 24 patients who received treatment with open-label vedolizumab; these patients were included only in the safety population for induction. These 75 patients (cohort 1 and cohort 2 combined) included 34 patients from India, 26 from South Korea, 9 from Malaysia, 3 from Taiwan, 2 from Hong Kong, and 1 patient from Singapore (Supplementary Tables 1, 2). A total of 30 patients (51.7%) showed response to vedolizumab at 6 weeks and were randomized in the maintenance phase–12 were randomized to vedolizumab q4w, 11 to vedolizumab 8qw and 7 to placebo (maintenance ITT population). Twenty-four patients (41.4%) failed to show response to vedolizumab at 6 weeks and received open-label vedolizumab during maintenance; 4 patients (6.9%) who were treated with vedolizumab discontinued the study during the induction phase. A total of 17 patients who received placebo during induction continued to receive it during maintenance.

2) Demography and Baseline Characteristics

Tables 1 and 2 show the baseline and demographic data for the Asian subgroup. In the induction phase, the median duration of CD was 2.9 years (range, 0.5–14.2 years) in the vedolizumab cohort 1 and 2.7 years (range, 0.7–9.9 years) in the placebo group. Approximately, 2 in 3 patients (48/75, 64.0%) had received prior treatment with glucocorticoids and/or immunomodulators. In the induction phase, 14.7% of the patients in vedolizumab cohort 1 and 23.5% of those in the placebo group had received prior anti-TNF treatment.

Table 1.

Characteristics in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Induction Phase

| Parameter | Placebo | Vedolizumab (cohort 1) | Vedolizumab (cohort 2) | Vedolizumab (combined) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 17 | 34 | 24 | 58 |

| Male sex | 7 (41) | 20 (59) | 16 (67) | 36 (62) |

| Age (yr) | 32.4 ± 8.7 | 32.4 ± 10.6 | 30.5 ± 8.5 | 31.6 ± 9.8 |

| Body weight (kg) | 53.4 ± 15.9 | 49.0 ± 10.0 | 51.5 ± 10.3 | 50.0 ± 10.1 |

| Duration of CD (yr) | 2.7 (0.7–9.9) | 2.9 (0.5–14.2) | 3.6 (1.1–14.0) | 3.4 (0.5–14.2) |

| Concomitant medications for CD | ||||

| Only glucocorticoids | 2 (12) | 6 (18) | 5 (21) | 11 (19) |

| Only immunomodulators | 2 (12) | 8 (24) | 6 (25) | 14 (24) |

| Glucocorticoids and immunomodulators | 6 (35) | 7 (21) | 6 (25) | 13 (22) |

| No glucocorticoids or immunomodulators | 7 (41) | 13 (38) | 7 (29) | 20 (34) |

| Patients with prior anti-TNF use | 4 (24) | 5 (15) | 6 (25) | 11 (19) |

| Patients with prior anti-TNF failure | 4 (24) | 4 (12) | 5 (21) | 9 (16) |

| CDAI score | 349 ± 82 | 343 ± 89 | 320 ± 69 | 333 ± 82 |

Values are presented as number (%), mean±standard deviation, or median (range).

Placebo and vedolizumab (cohort 1)=the groups that were part of the double-blind induction phase (induction intent-to-treat [ITT] population); Vedolizumab (cohort 2)=additional patients were enrolled to meet the maintenance phase sample size requirements and received open-label vedolizumab (induction safety population only); Vedolizumab (combined)=all patients that received vedolizumab during the induction phase.

CD, Crohn’s disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; CDAI, Crohn’s Disease Activity Index.

Table 2.

Characteristics in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Maintenance Phase

| Parameter | ITT |

Non-ITT |

Placebo combined | Vedolizumab combined | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Vedolizumab q8w | Vedolizumab q4w | Placeboa | Vedolizumab q4wa | ||||

| No. | 7 | 11 | 12 | 17 | 28 | 24 | 51 | |

| Male sex | 3 (43) | 6 (55) | 8 (67) | 7 (41) | 19 (68) | 10 (42) | 33 (65) | |

| Age (yr) | 34.5 ± 4.7 | 38.8 ± 13.2 | 27.2 ± 6.5 | 32.4 ± 8.7 | 30.0 ± 8.9 | 33.0 ± 7.7 | 31.3 ± 10.2 | |

| Body weight (kg) | 46.0 ± 11.7 | 51.2 ± 9.3 | 53.7 ± 7.6 | 53.4 ± 15.9 | 49.0 ± 10.8 | 51.2 ± 15.0 | 50.6 ± 9.8 | |

| Duration of CD (yr) | 3.1 (1.1–11.1) | 4.1 (1.1–14.0) | 4.1 (0.6–14.2) | 2.7 (0.7–9.9) | 3.4 (0.5–13.8) | 2.9 (0.7–11.1) | 3.7 (0.5–14.2) | |

| Concomitant medications for CD | ||||||||

| Only glucocorticoids | 1 (14) | 2 (18) | 2 (17) | 2 (12) | 6 (21) | 3 (13) | 10 (20) | |

| Only immunomodulators | 1 (14) | 3 (27) | 5 (42) | 2 (12) | 5 (18) | 3 (13) | 13 (25) | |

| Glucocorticoids and immunomodulators | 2 (29) | 3 (27) | 3 (25) | 6 (35) | 5 (18) | 8 (33) | 11 (22) | |

| No glucocorticoids or immunomodulators | 3 (43) | 3 (27) | 2 (17) | 7 (41) | 12 (43) | 10 (42) | 17 (33) | |

| Patients with prior anti-TNF use | 0 | 2 (18) | 2 (17) | 4 (24) | 7 (25) | 4 (17) | 11 (22) | |

| Patients with prior anti-TNF failure | 0 | 1 (9) | 1 (8) | 4 (24) | 7 (25) | 4 (17) | 9 (18) | |

| CDAI score | 329 ± 82 | 326 ± 80 | 310 ± 97 | 349 ± 82 | 347 ± 77 | 343 ± 81 | 334 ± 83 | |

83Values are presented as number (%), mean±standard deviation, or median (range).

Intent-to-treat (ITT)=patients who showed response to vedolizumab at 6 weeks and were randomized as part of the double-blind maintenance phase (maintenance ITT population); Non-ITT placebo=patients that were randomized to placebo during the induction phase and continued to received double-blind placebo during maintenance phase (maintenance safety population only); Non-ITT vedolizumab q4w=patients that did not show response to vedolizumab at 6 weeks and received open-label vedolizumab during the maintenance phase (maintenance safety population only); Placebo combined=all patients that received placebo during the maintenance phase; Vedolizumab combined=all patients that received vedolizumab during the maintenance phase.

Patient numbers do not exactly match those shown in disposition (Fig. 1) because those patients who were discontinued from the study during the induction phase continued to be included in the safety population and have been counted within these groups.

q4w, every 4 weeks; q8w, every 8 weeks; CD, Crohn’s disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; CDAI, Crohn’s Disease Activity Index.

3) Efficacy

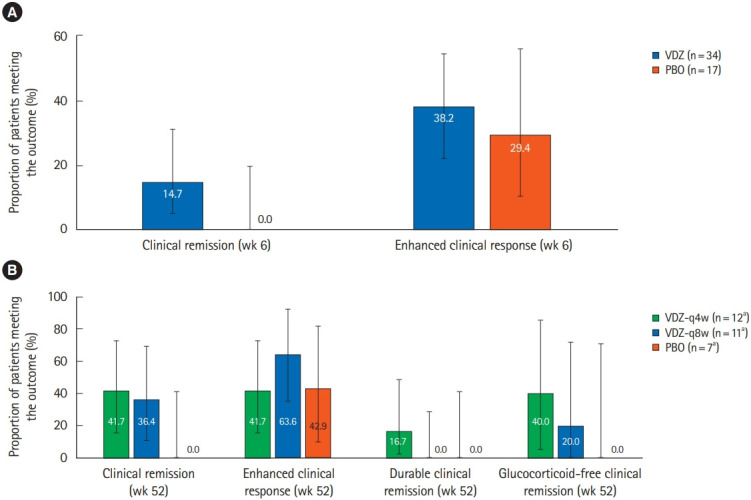

Fig. 2 shows the efficacy results for the Asian subgroup. During the induction phase (Fig. 2A), 14.7% (95% CI, 5.0%–31.1%) of the patients with vedolizumab achieved clinical remission at week 6 compared to none in the placebo group (difference from placebo = 14.7%; 95% confidence intervals, 15.8%–43.5%). The proportion of Asian subgroup patients achieving enhanced clinical response in the induction phase was also numerically higher with vedolizumab than placebo (38.2% vs. 29.4%, respectively). The median change from baseline in CRP levels was broadly comparable across the vedolizumab and placebo groups (0.2 mg/L vs. –3.6 mg/L, respectively) (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Comparison of efficacy results for vedolizumab (VDZ) versus placebo (PBO) in the Asian countries subgroup in GEMINI 2 patients (A) in the induction phase, in the induction intent-to-treat (ITT) population, the rates of clinical remission and enhanced clinical response were numerically higher with VDZ compared to PBO, (B) in the maintenance phase, in the maintenance ITT population, the rates of remission and response were numerically higher with the VDZ groups compared to PBO. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. aFor glucocorticoid-free remission, the analysis was restricted to patients who were on glucocorticoids at baseline; therefore the “n” numbers for VDZ q4w, VDZ q8w, and PBO were 5, 5, and 3, respectively. q4w, every 4 weeks; q8w, every 8 weeks.

Table 3.

Comparison of Change in CRP Scores for Vedolizumab versus Placebo in the Asian Countries Subgroup in GEMINI 2 Patients in the Induction Phase

| CRP level | Placebo | Vedolizumab |

|---|---|---|

| All patients | ||

| No. | 17 | 34 |

| Baseline | 28.9 ± 35.9 | 36.6 ± 38.0 |

| Week 6 | 16.2 ± 13.5 | 38.0 ± 38.5 |

| Change from baseline | –12.7 ± 34.5 | 1.4 ± 18.6 |

| Median change from baseline | –3.6 | 0.2 |

| 10th and 90th percentile | (–27.6, 4.1) | (–15.0, 10.1) |

| Patients with baseline CRP > 2.87 mg/L | ||

| No. | 16 | 31 |

| Baseline | 30.7 ± 36.3 | 40.0 ± 38.0 |

| Week 6 | 17.2 ± 13.3 | 41.6 ± 38.5 |

| Change from baseline | –13.5 ± 35.4 | 1.5 ± 19.5 |

| Median change from baseline | –4.0 | 0.0 |

| 10th and 90th percentile | (–27.6, 4.1) | (–15.0, 10.1) |

Values are presented as mean±standard deviation or unless otherwise stated.

CRP, C-reactive protein.

During the maintenance phase (Fig. 2B), clinical remission at week 52 was achieved in 36.4% (95% CI, 10.9%–69.2%) of patients with vedolizumab q8w and 41.7% (95% CI, 15.2%–72.3%) of patients with vedolizumab q4w, compared to 0% with placebo. Enhanced clinical response at week 52 was achieved in 63.6% (95% CI, 35.2%–92.1%) of patients with vedolizumab q8w and 41.7% (95% CI, 15.2%–72.3%) of patients with vedolizumab q4w, compared to 42.9% (95% CI, 9.9%–81.6%) with placebo. Twenty percent of those treated with vedolizumab q8w and 40% of those treated with vedolizumab q4w achieved glucocorticoid-free remission, while none of the placebo patients achieved the outcome. For the outcome of glucocorticoid-free remission, the analysis included very few patients–5 patients each in the 2 vedolizumab arms and 3 patients in the placebo arm. Although the rates of clinical remission and response were numerically higher within the vedolizumab groups compared to placebo, the number of patients in these analyses was small, with a total of 30 patients across the 3 groups. The rate of clinical remission, enhanced clinical response, and durable clinical remission was 36.4%, 63.6%, and 0.0%, respectively, in the vedolizumab q8w group, and 41.7%, 41.7%, and 16.7%, respectively, in the vedolizumab q4w group.

4) Safety

The frequency of adverse events (AEs) in the safety population of the Asian subgroup is shown in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4. During induction, 39.7% of patients with vedolizumab experienced an AE compared to 58.8% of patients with placebo. The frequency of drug-related AEs was 8.6% and 23.5% in the vedolizumab and placebo groups, respectively. Across both groups, the frequency of serious AEs (SAEs) and serious infections was low during induction–5.2% and 1.7%, respectively, in the vedolizumab group, and 5.9% and 0%, respectively, in the placebo group. During the maintenance phase, 13.7% of patients with vedolizumab experienced AEs resulting in study discontinuation compared to none with placebo. The frequency of SAEs was 27.5% with vedolizumab compared to 8.3% with placebo, and the frequency of serious infections was 13.7% with vedolizumab compared to none with placebo. Two deaths were reported in the vedolizumab group during the maintenance phase–one death each from sepsis and septic shock. The sepsis event involved a patient with medically managed pneumoperitoneum after colonoscopy, and the septic shock event involved a patient with extensive preexisting pulmonary emboli and a thrombus in the inferior vena cava. Both these events had been reviewed by an independent data safety monitoring board, which recommended that no changes be made to the study conduct on the basis of its review of these cases.

During the induction phase, AEs affecting at least 5% of patients receiving vedolizumab in the safety population were (vedolizumab vs. placebo)–lymphopenia (6.9% vs. 11.8%), and headache (5.2% vs. 0%). During the maintenance phase, AEs affecting at least 10% of patients receiving vedolizumab in the safety population were (vedolizumab vs. placebo)–exacerbation of CD (11.8% vs. 8.3%), diarrhea (9.8% vs. 8.3%), nasopharyngitis (11.8% vs. 4.2%), pyrexia (25.5% vs. 29.2%), lymphopenia (11.8% vs. 12.5%), and anemia (9.8% vs. 4.2%). None of the patients in the Asian subgroup developed TB, hepatitis B virus (HBV) or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection during the study.

2. Non-Asian Countries Subgroup

1) Disposition

The disposition of the non-Asian subgroup of the GEMINI 2 study is shown in Fig. 1. Cohort 1 consisted of 317 patients, of whom 186 patients were randomized to vedolizumab and 131 to placebo during induction (induction ITT population). Cohort 2 consisted of 723 patients who received treatment with open-label vedolizumab; these patients were included only in the safety population for induction. A total of 431 patients (47.4%) showed response to vedolizumab at 6 weeks and were randomized in the maintenance phase–142 to vedolizumab q4w, 143 to vedolizumab 8qw and 146 to placebo. Three hundred and eighty-eight patients (42.7%) failed to show response to vedolizumab at 6 weeks and received open-label vedolizumab during maintenance; 90 patients (9.9%) who were treated with vedolizumab discontinued the study during the induction phase. A total of 120 patients who received placebo during induction continued to receive it during maintenance.

2) Demography and Baseline Characteristics

The baseline and demographic characteristics are presented in Tables 4 and 5. In the non-Asian subgroup, the median duration of CD was 8.0 years (range, 0.5–43.6 years) in the vedolizumab cohort 1 and 6.6 years (range, 0.3–42.0 years) in the placebo group. Prior treatment with glucocorticoids and/or immunomodulators had been received by 65.1% and 65.6% of the patients in the vedolizumab cohort 1 and placebo groups, respectively, while prior treatment with anti-TNF agents had been received by 57.0% and 51.9% patients, respectively.

Table 4.

Characteristics in the Non-Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Induction Phase

| Parameter | Placebo | Vedolizumab (cohort 1) | Vedolizumab (cohort 2) | Vedolizumab (combined) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 131 | 186 | 723 | 909 | |

| Male sex | 62 (47) | 85 (46) | 330 (46) | 415 (46) | |

| Age (yr) | 39.4 ± 13.5 | 37.0 ± 11.6 | 35.7 ± 12.1 | 36.0 ± 12.0 | |

| Body weight (kg) | 70.7 ± 18.4 | 70.4 ± 18.5 | 71.4 ± 19.5 | 71.2 ± 19.3 | |

| Duration of CD (yr) | 6.6 (0.3–42.0) | 8.0 (0.5–43.6) | 7.5 (0.2–42.5) | 7.6 (0.2–43.6) | |

| Concomitant medications for CD | |||||

| Only glucocorticoids | 43 (33) | 61 (33) | 264 (37) | 325 (36) | |

| Only immunomodulators | 23 (18) | 29 (16) | 113 (16) | 142 (16) | |

| Glucocorticoids and immunomodulators | 20 (15) | 31 (17) | 119 (16) | 150 (17) | |

| No glucocorticoids or immunomodulators | 45 (34) | 65 (35) | 227 (31) | 292 (32) | |

| Patients with prior anti-TNF use | 68 (52) | 106 (57) | 500 (69) | 606 (67) | |

| Patients with prior anti-TNF failure | 66 (50) | 101 (54) | 465 (64) | 566 (62) | |

| CDAI score | 322 ± 77 | 325 ± 67 | 322 ± 67 | 323 ± 67 | |

Values are presented as number (%), mean±standard deviation, or median (range).

Placebo and vedolizumab (cohort 1)=the groups that were part of the double-blind induction phase (induction intent-to-treat [ITT] population); Vedolizumab (cohort 2)=additional patients were enrolled to meet the maintenance phase sample size requirements and received open-label vedolizumab (induction safety population only); Vedolizumab (combined)=all patients that received vedolizumab during the induction phase.

CD, Crohn’s disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; CDAI, Crohn’s Disease Activity Index.

Table 5.

Characteristics in the Non-Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Maintenance Phase

| Parameter | ITT |

Non-ITT |

Placebo combined | Vedolizumab combined | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | Vedolizumab q8w | Vedolizumab q4w | Placeboa | Vedolizumab q4wa | ||||

| No. | 146 | 143 | 142 | 131 | 478 | 277 | 763 | |

| Male sex | 69 (47) | 62 (43) | 74 (52) | 62 (47) | 210 (44) | 131 (47) | 346 (45) | |

| Age (yr) | 37.4 ± 12.2 | 34.8 ± 12.2 | 35.6 ± 12.4 | 39.4 ± 13.5 | 36.1 ± 11.8 | 38.3 ± 12.8 | 35.7 ± 12.0 | |

| Body weight (kg) | 70.1 ± 17.7 | 69.9 ± 18.4 | 73.0 ± 18.2 | 70.7 ± 18.4 | 71.4 ± 20.3 | 70.4 ± 18.0 | 71.4 ± 19.6 | |

| Duration of CD (yr) | 7.4 (0.3–43.6) | 6.5 (0.3–34.7) | 6.8 (0.2–42.5) | 6.6 (0.3–42.0) | 8.5 (0.3–42.8) | 6.9 (0.3–43.6) | 7.6 (0.2–42.8) | |

| Concomitant medications for CD | ||||||||

| Only glucocorticoids | 55 (38) | 57 (40) | 56 (39) | 43 (33) | 157 (33) | 98 (35) | 270 (35) | |

| Only immunomodulators | 22 (15) | 24 (17) | 26 (18) | 23 (18) | 70 (15) | 45 (16) | 120 (16) | |

| Glucocorticoids and immunomodulators | 24 (16) | 20 (14) | 19 (13) | 20 (15) | 87 (18) | 44 (16) | 126 (17) | |

| No glucocorticoids or immunomodulators | 45 (31) | 42 (29) | 41 (29) | 45 (34) | 164 (34) | 90 (32) | 247 (32) | |

| Patients with prior anti-TNF use | 82 (56) | 86 (60) | 81 (57) | 68 (52) | 357 (75) | 150 (54) | 524 (69) | |

| Patients with prior anti-TNF failure | 78 (53) | 81 (57) | 76 (54) | 66 (50) | 331 (69) | 144 (52) | 488 (64) | |

| CDAI score | 325 ± 65 | 326 ± 68 | 318 ± 63 | 322 ± 77 | 323 ± 69 | 323 ± 71 | 322 ± 67 | |

Values are presented as number (%), mean±standard deviation, or median (range).

Intent-to-treat (ITT)=patients who showed response to vedolizumab at 6 weeks and were randomized as part of the double-blind maintenance phase (maintenance ITT population); Non-ITT placebo=patients that were randomized to placebo during the induction phase and continued to received double-blind placebo during maintenance phase (maintenance safety population only); Non-ITT vedolizumab q4w=patients that did not show response to vedolizumab at 6 weeks and received open-label vedolizumab during the maintenance phase (maintenance safety population only); Placebo combined=all patients that received placebo during the maintenance phase; Vedolizumab combined=all patients that received vedolizumab during the maintenance phase.

Patient numbers do not exactly match those shown in disposition (Fig. 1) because those patients who were discontinued from the study during the induction phase continued to be included in the safety population and have been counted within these groups.

q4w, every 4 weeks; q8w, every 8 weeks; CD, Crohn’s disease; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; CDAI, Crohn’s Disease Activity Index.

3) Efficacy

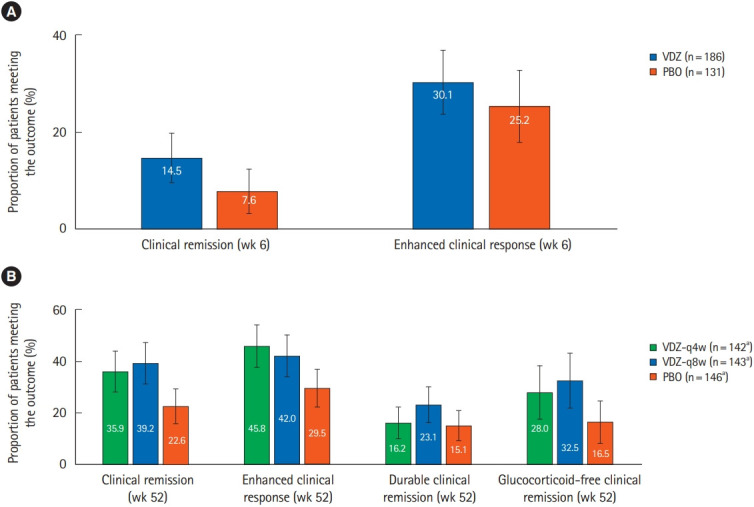

The efficacy results in the non-Asian subgroup are shown in Fig. 3. During induction (Fig. 3A), the efficacy rates were numerically higher with vedolizumab than placebo–clinical remission (14.5% vs. 7.6%) and enhanced clinical response (30.1% vs. 25.2%). Similarly, during the maintenance phase (Fig. 3B), the efficacy rates were consistently numerically higher in both vedolizumab groups compared to placebo–clinical remission rates for vedolizumab q4w, vedolizumab q8w and placebo groups were 35.9%, 39.2%, and 22.6%, respectively; and enhanced clinical response rates were 45.8%, 42.0%, and 29.5%, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of efficacy results for vedolizumab (VDZ) versus placebo (PBO) in the non-Asian countries subgroup in GEMINI 2 patients (A) in the induction phase, in the induction intent-to-treat (ITT) population, the rates of clinical remission and enhanced clinical response were numerically higher with VDZ compared to PBO, (B) in the maintenance phase, in the maintenance ITT population, the efficacy rates were higher in both VDZ groups compared to PBO for all outcomes. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. aFor glucocorticoid-free remission, the analysis was restricted to patients who were on glucocorticoids at baseline; therefore the “n” numbers for VDZ q4w, VDZ q8w, and PBO were 75, 77, and 79, respectively. q4w, every 4 weeks; q8w, every 8 weeks.

4) Safety

Supplementary Tables 5 and 6 provide detailed information regarding AE frequencies for the safety population within the non-Asian subgroup. During induction, the frequency of AEs was 58.0% for those receiving vedolizumab and 59.5% for those receiving placebo; during maintenance, the frequencies were 87.0% and 81.6%, respectively. Serious infections were infrequent–1.1% and 1.5%, respectively, for vedolizumab and placebo during induction; and 5.0% and 3.2%, respectively, during maintenance. In the induction phase, AEs affecting at least 5% of patients receiving vedolizumab in the safety population were nausea (6.2% in vedolizumab, 6.9% in placebo), exacerbation of CD (6.1%, 7.6%), pyrexia (5.3%, 0.8%), and headache (7.7%, 9.2%). In the maintenance phase, AEs affecting at least 10% of patients receiving vedolizumab in the safety population were exacerbation of CD (20.7% in vedolizumab, 22.7% in placebo), nausea (11.4%, 10.5%), nasopharyngitis (12.3%, 8.3%), arthralgia (14.0%, 12.3%), pyrexia (11.8%, 11.9%), and headache (12.6%, 15.5%).

DISCUSSION

In this post-hoc analysis of the GEMINI 2 study, data on patients from 6 Asian countries has been analyzed.

In the Asian subgroup, during induction treatment, the remission and response rates were numerically higher with vedolizumab than placebo. Approximately, 15% of the patients in the vedolizumab group achieved clinical remission compared to none in the placebo group and enhanced clinical response rates were also numerically higher with vedolizumab than placebo. Similarly, during maintenance treatment, the remission and response rates were numerically higher with vedolizumab than placebo. In the non-Asian subgroup, which included a much larger sample, the results showed a similar trend, and efficacy rates were numerically higher with vedolizumab compared to placebo.

In the Asian subgroup, during the maintenance phase, certain AEs were numerically more frequent with vedolizumab than with placebo, especially AEs resulting in study discontinuation, SAEs during maintenance and serious infection AEs during maintenance. Of note, based on an analysis of the integrated safety data from multiple vedolizumab clinical trials, which included both Asian and non-Asian patients, the overall safety profile of vedolizumab versus placebo was similar in CD [19]. Most of the common AEs reported in the Asian subgroup (headache, nasopharyngitis, pyrexia) were along expected lines, and were consistent with the common AEs reported in the overall cohort in GEMINI 2 [14].

Our study adds to the limited data currently available on the use of vedolizumab in IBD in patients from Asian countries. Recent studies from Japan [23,24] (involving 292 patients with UC and 157 with CD, as part of a bridging study), Singapore [25] (involving 28 patients with CD), Taiwan [26] (involving 24 patients with IBD), and South Korea [27] (involving 36 patients with treatment-refractory CD) also support the benefits of vedolizumab in this population. There does, however, remain a need for additional real-world evidence to better characterize the effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in CD, in real clinical practice.

The primary limitation of our analysis is the small sample size of the Asian subgroup, which resulted in wide confidence intervals for this subgroup, and especially impacts the robustness of the safety data analysis. Given the small sample size, formal statistical comparisons of the vedolizumab-placebo differences in the Asian subgroup could not be conducted.

The risk of opportunistic infections with anti-TNF agents is 2.05 times that with placebo, while the risk of TB infection is 2.52 times that with placebo in controlled trials [28]. In the realworld, approximately 1% to 2% of IBD patients receiving treatment with anti-TNF agents develop active TB [28-32]. Whilst screening for TB helps mitigate this risk to some extent, TB reactivation with anti-TNF agents is also known to occur despite adequate screening [31-35]. This increased risk of opportunistic infections is particularly relevant in Asia, where TB is highly prevalent; in 2016, an estimated 10.4 million people suffered with TB of which 45% were from the WHO South-East Asia Region [36]. There is therefore a need for newer biological agents in CD with a lower risk of opportunistic infections. Vedolizumab, being gut-selective, is likely to cause fewer opportunistic infections, including TB. In the GEMINI 1 and 2 studies, in which patients were screened for latent TB at study entry, a single case of TB was reported with vedolizumab treatment–latent TB in a 38-year-old male patient from the Czech Republic. Overall, the reported rate of TB with vedolizumab treatment is 0.1 per 100 patient-years in clinical trials, and less than 7 per 100,000 patient-years in post-marketing settings [17-19]. A similar trend towards low risk of opportunistic infections in patients from Asian countries would likely impact clinical practice particularly in the choice among biologics. Another important consideration is the high rate of HBV infection in Asian countries [37]. Patients with chronic HBV and HCV infection were excluded from the GEMINI trials; in the post-marketing setting, over 114,071 patient-years of vedolizumab treatment, there were 29 patients with a history of or concurrent HBV/HCV infection, none of whom reported viral reactivation after vedolizumab treatment [17].

In summary, this post-hoc analysis demonstrates the treatment effect and safety of vedolizumab in moderate-to-severely active CD in patients from Asian countries. With increasing utilization of vedolizumab, confirmation of these results is expected from future real-world studies in Asia.

Footnotes

Funding Source

The study was funded by Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Ltd.

Conflict of Interest

Clinical trials were sponsored and conducted by Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Ltd. Medical writing support was sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Ltd. Demuth D, Lindner D, and Adsul S are employees of Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Ltd. The other authors report no conflict of interest.

Author Contribution

Conceptualization: Banerjee R, Hilmi IN, Wu DC, Demuth D, Lindner D, Adsul S. Methodology: Banerjee R, Hilmi IN, Wu DC, Demuth D, Lindner D, Adsul S. Formal analysis: Demuth D, Lindner D, Adsul S. Project administration: Banerjee R, Hilmi IN, Demuth D, Lindner D, Adsul S. Visualization: Banerjee R, Hilmi IN, Wu DC, Demuth D, Lindner D, Adsul S. Writing - original draft: Demuth D, Lindner D, Adsul S. Writing - review and editing: Banerjee R, Hilmi IN, Wu DC, Demuth D, Lindner D, Adsul S. Approval of final manuscript: all authors.

Others

The authors thank the patients and their caregivers in addition to the investigators and their teams who contributed to this study. Medical writing support was provided by Assansa, India (a Healthcare Consultancy-Assansa consultants Dr. Aamir Shaikh MD, Dr. Saifuddin Kharawala MBBS, DPM) and sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceuticals Company Ltd.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary materials are available at the Intestinal Research website (https://www.irjournal.org).

Supplementary Table 1. Country-Wise Distribution of Patients in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Induction Phase

Supplementary Table 2. Country-Wise Distribution of Patients in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Maintenance Phase

Supplementary Table 3. Key Safety Results in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Induction Phase

Supplementary Table 4. Key Safety Results in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Maintenance Phase

Supplementary Table 5. Key Safety Results in the Non-Asian Countries Subgroup in GEMINI 2 Patients: Induction Phase

Supplementary Table 6. Key Safety Results in the Non-Asian Countries Subgroup in GEMINI 2 Patients: Maintenance Phase

REFERENCES

- 1.Molodecky NA, Soon IS, Rabi DM, et al. Increasing incidence and prevalence of the inflammatory bowel diseases with time, based on systematic review. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:46–54. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ng SC, Tsoi KK, Kamm MA, et al. Genetics of inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:1164–1176. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim ES, Kim WH. Inflammatory bowel disease in Korea: epidemiological, genomic, clinical, and therapeutic characteristics. Gut Liver. 2010;4:1–14. doi: 10.5009/gnl.2010.4.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prideaux L, Kamm MA, De Cruz PP, Chan FK, Ng SC. Inflammatory bowel disease in Asia: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;27:1266–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2012.07150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ng SC. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease: focus on Asia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang YF, Zhang H, Ouyang Q. Clinical manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: East and West differences. J Dig Dis. 2007;8:121–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-9573.2007.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amarapurkar DN, Patel ND, Rane PS. Diagnosis of Crohn’s disease in India where tuberculosis is widely prevalent. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:741–746. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang SK, Yun S, Kim JH, et al. Epidemiology of inflammatory bowel disease in the Songpa-Kangdong district, Seoul, Korea, 1986-2005: a KASID study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14:542–549. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ng SC, Kaplan GG, Tang W, et al. Population density and risk of inflammatory bowel disease: a prospective population-based study in 13 countries or regions in Asia-Pacific. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114:107–115. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0233-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ooi CJ, Makharia GK, Hilmi I, et al. Asia Pacific Consensus Statements on Crohn’s disease. Part 1: definition, diagnosis, and epidemiology (Asia Pacific Crohn’s Disease Consensus: part 1) J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:45–55. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ooi CJ, Makharia GK, Hilmi I, et al. Asia-Pacific Consensus Statements on Crohn’s disease. Part 2: management. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;31:56–68. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong U, Cross RK. Primary and secondary nonresponse to infliximab: mechanisms and countermeasures. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2017;13:1039–1046. doi: 10.1080/17425255.2017.1377180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. National Library of Medicine: ClinicalTrials.gov Study of vedolizumab (MLN0002) in patients with moderate to severe Crohn’s disease (GEMINI II) [Internet] c2014 [cited 2018 Mar 30]. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00783692.

- 14.Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, Rutgeerts P, et al. Vedolizumab as induction and maintenance therapy for Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:711–721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1215739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schreiber S, Dignass A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: real-world effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2018;53:1048–1064. doi: 10.1007/s00535-018-1480-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luthra P, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Ford AC. Systematic review and meta-analysis: opportunistic infections and malignancies during treatment with anti-integrin antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1227–1236. doi: 10.1111/apt.13215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng SC, Hilmi IN, Blake A, et al. Low frequency of opportunistic infections in patients receiving vedolizumab in clinical trials and post-marketing setting. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2018;24:2431–2441. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Amiot A, Grimaud JC, Peyrin-Biroulet L, et al. Effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab induction therapy for patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;14:1593–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Colombel JF, Sands BE, Rutgeerts P, et al. The safety of vedolizumab for ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. Gut. 2017;66:839–851. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cheon JH. Understanding the complications of anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in East Asian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:769–777. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung WK, Ng SC, Chow DK, et al. Use of biologics for inflammatory bowel disease in Hong Kong: consensus statement. Hong Kong Med J. 2013;19:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leung WK. Optimization of inflammatory bowel disease cohort studies in Asia. Intest Res. 2015;13:208–212. doi: 10.5217/ir.2015.13.3.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Motoya S, Watanabe K, Ogata H, et al. Vedolizumab in Japanese patients with ulcerative colitis: a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0212989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0212989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe K, Motoya S, Ogata H, et al. Effects of vedolizumab in Japanese patients with Crohn’s disease: a prospective, multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial with exploratory analyses. J Gastroenterol. 2020;55:291–306. doi: 10.1007/s00535-019-01647-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gan AT, Chan WP, Ling KL, et al. P634 Real-world data on the efficacy and safety of vedolizumab therapy in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a retrospective nation-wide cohort study in Singapore. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13 Suppl 1:S434–S435. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chiu YC, Chen CC, Ko WC, Liao SC, Yeh HZ, Chang CH. Real‐ world efficacy and safety of vedolizumab among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a single tertiary medical center experience in Central Taiwan. Adv Dig Med. doi: 10.1002/aid2.13188. [published online ahead of print February 19, 2020]. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim J, Ham NS, Oh EH, et al. Real life effectiveness and safety of vedolizumab induction and maintenance therapy for Korean IBD patients in whom anti-TNF treatment failed: a prospective cohort study. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13 Suppl 1:S237. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ford AC, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Opportunistic infections with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy in inflammatory bowel disease: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1268–1276. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hong SN, Kim HJ, Kim KH, Han SJ, Ahn IM, Ahn HS. Risk of incident Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a nationwide population-based study in South Korea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:253–263. doi: 10.1111/apt.13851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mañosa M, Domènech E, Cabré E. Current incidence of active tuberculosis in IBD patients treated with anti-TNF agents: still room for improvement. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:e499–e500. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Byun JM, Lee CK, Rhee SY, et al. The risk of tuberculosis in Korean patients with inflammatory bowel disease receiving tumor necrosis factor-α blockers. J Korean Med Sci. 2015;30:173–179. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.2.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jauregui-Amezaga A, Turon F, Ordás I, et al. Risk of developing tuberculosis under anti-TNF treatment despite latent infection screening. J Crohns Colitis. 2013;7:208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2012.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Puri AS, Desai D, Sood A, Sachdeva S. Infliximab-induced tuberculosis in patients with UC: experience from India-a country with high prevalence of tuberculosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;32:1191–1194. doi: 10.1111/jgh.13669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Navarra SV, Raso A, Lichauco JJ, Tan PP. Clinical experience with infliximab among Filipino patients with rheumatic diseases. APLAR J Rheumatol. 2006;9:150–156. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carpio D, Jauregui-Amezaga A, de Francisco R, et al. Tuberculosis in anti-tumour necrosis factor-treated inflammatory bowel disease patients after the implementation of preventive measures: compliance with recommendations and safety of retreatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1186–1193. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.World Health Organization Global tuberculosis report 2017 [Internet] c2017 [cited 2018 Mar 30]. http://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/

- 37.Shan S, Cui F, Jia J. How to control highly endemic hepatitis B in Asia. Liver Int. 2018;38 Suppl 1:122–125. doi: 10.1111/liv.13625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1. Country-Wise Distribution of Patients in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Induction Phase

Supplementary Table 2. Country-Wise Distribution of Patients in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Maintenance Phase

Supplementary Table 3. Key Safety Results in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Induction Phase

Supplementary Table 4. Key Safety Results in the Asian Countries Subgroup of GEMINI 2 Patients: Maintenance Phase

Supplementary Table 5. Key Safety Results in the Non-Asian Countries Subgroup in GEMINI 2 Patients: Induction Phase

Supplementary Table 6. Key Safety Results in the Non-Asian Countries Subgroup in GEMINI 2 Patients: Maintenance Phase