Abstract

Objectives

To provide systematically evaluated evidence of prospective associations between exposure to physical, psychological and gender-based violence and health among healthcare, social care and education workers.

Methods

The guidelines on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses were followed. Medline, Cinahl, Web of Science and PsycInfo were searched for population: human service workers; exposure: workplace violence; and study type: prospective or longitudinal in articles published 1990–August 2019. Quality assessment was performed based on a modified version of the Cochrane’s ‘Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Cohort Studies’.

Results

After deduplication, 3566 studies remained, of which 132 articles were selected for full-text screening and 28 were included in the systematic review. A majority of the studies focused on healthcare personnel, were from the Nordic countries and were assessed to have medium quality. Nine of 11 associations between physical violence and poor mental health were statistically significant, and 3 of 4 associations between physical violence and sickness absence. Ten of 13 associations between psychological violence and poor mental health were statistically significant and 6 of 6 associations between psychological violence and sickness absence. The only study on gender-based violence and health reported a statistically non-significant association.

Conclusion

There is consistent evidence mainly in medium quality studies of prospective associations between psychological violence and poor mental health and sickness absence, and between physical violence and poor mental health in human service workers. More research using objective outcomes, improved exposure assessment and that focus on gender-based violence is needed.

Keywords: mental health, longitudinal studies, sickness absence, violence, healthcare workers

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Workplace violence is prevalent in human service industries, and associations between workplace violence and health outcomes have been reported. However, a synthesis of results based on prospective or longitudinal data of associations between different forms of workplace violence and health outcomes in human service industries is lacking.

What are the new findings?

The results of the systematic review indicate consistent evidence mainly in medium quality studies of prospective associations between psychological violence and poor mental health and sickness absence, and between physical violence and poor mental health in human service workers. More research with objective outcomes, improved exposure assessment and that focus on gender-based violence is needed.

How might this impact on policy or clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

The evidence of the present review supports the need to develop guidelines for readily detecting and dealing with workplace violence in the human service industries.

Introduction

Workplace violence has been acknowledged as a major workplace hazard and has been studied for at least 30 years,1–3 but the research on its antecedents and consequences has expanded and advanced methodologically primarily during the past 15 years. There is no consensus in the literature on a definition of workplace violence, and a large variation of definitions is found across studies. The most recent definition was presented in the Violence and Harassment Convention 20194 by the International Labour Organization (ILO):

Violence and harassment in the world of work refers to a range of unacceptable behaviours and practices, or threats thereof, whether a single occurrence or repeated, that aim at, result in, or are likely to result in physical, psychological, sexual or economic harm, and includes gender-based violence and harassment.

The reported prevalences of workplace violence vary greatly. For example, in a research review the percentage of hospital employees exposed to verbal violence from patients varied between 22% and 90% across studies, exposure to threats of violence and actual violence between 12% and 64%, and exposure to physical assault between 2% and 32%.5 When comparing different labour market sectors, it is however evident that employees in some sectors are more exposed to violence than others. The prevalence of physical violence has, in international reviews, been reported to be particularly high in healthcare, education, public safety, retail and justice industries.1 6 7 According to a recent systematic review and meta-analysis, 61.9% of healthcare personnel reported exposure to physical or non-physical workplace violence by patients and visitors in the past year.8

Human service industries include healthcare, social care and education, providing care and education to patients, children, elderly or clients, and employ a large part of the workforce, particularly the female one, in most countries. The risk of mental ill-health and sickness absence among employees in these industries, as compared with other industries, is higher and has increased in later years.9–13 Poorer working conditions, not least exposure to workplace violence by patients and clients, have been suggested as major explanations.10 14 Employees in these industries are not, in contrast to, for example, protection workers that are also exposed to workplace violence, as well educated or prepared to handle violence. Professions with frequent contact with people in general, for example, within the retail industry, were not included because they have not been found to have elevated risks of mental ill-health13 or sickness absence,9 and workplace violence is less prevalent.13

To date, there is no synthesis of the evidence of associations between exposure to workplace violence and health outcomes among employees working in the human service industries. A large amount of review articles of workplace violence has focused on the healthcare industry.5 6 15–18 For example, Lanctôt and Guay published a review of cross-sectional and longitudinal studies of consequences of workplace violence by patients and visitors against healthcare workers, without distinctions between the different forms of violence (physical, psychological or gender-based).16 Because also the social care and education industries are highly exposed to workplace violence,1 6 7 a more comprehensive focus on these industries is well motivated. Only one review article of workplace violence among staff within the education system was identified by the authors.19 However, only employees within higher education were included in the review. The lack of prospective or longitudinal studies examining health consequences of workplace violence has been identified as a major research gap.16 Furthermore, workplace violence is a very broad concept, including exposures ranging from harassment to physical assault, with potentially different health outcomes, and distinctions between different forms of violence thus appear necessary. A systematic review of published prospective or longitudinal studies seems warranted to clarify the state of the evidence regarding health effects of various forms of workplace violence in the human service sectors.

Aim

Our aim was to provide systematically evaluated evidence of the prospective or longitudinal associations between exposure to physical, psychological and gender-based violence respectively by any perpetrator against human service workers, and health-related outcomes. The aim was furthermore to identify gaps in the research literature and provide guidelines for future research within the field.

Methods

The guidelines on Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA, see www.prisma-statement.org) were followed and a review protocol was registered (PROSPERO registration number: CRD42019128442). The literature searches were conducted by professionals at the University Library at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden, in February and August 2019. The review team consisted of a principal investigator (AN) and three additional researchers (GK, LMH and KR).

Search strategy and study selection

The strategy was developed by the review team in collaboration with the librarians. The databases Medline (OVID), Cinahl (EBSCO), Web of Science (Clarivate) and PsycInfo (OVID) were searched for articles published from 1990 until August 2019. The search was based on a combination of terms identifying exposure (workplace violence), population (employees in human service occupations and industries) and study type (prospective or longitudinal study). The full search strategy is given in online supplementary appendix A.

oemed-2020-106450supp001.pdf (21.7KB, pdf)

The inclusion criteria for the present study were (1) language: English; (2) population: employees in the human service industries healthcare, social care, and education; (3) exposure: workplace violence; (4) outcome: mental health, physical health, sickness absence and other health-related outcome; and (5) study type: study based on quantitative data and prospective or longitudinal study design with at least 30 participants exposed to workplace violence (if measured as a binary variable) or the level of exposure assessed in at least 30 participants (if measured on a continuous scale). We selected only original articles published in peer-reviewed journals; no book chapters, doctoral theses or other scientific reports were included.

First, the titles and abstracts identified by the search were screened against our inclusion criteria by the principal investigator and one more researcher in the review team. Discrepancies or uncertainties were discussed and resolved in the team. In case the titles and abstracts did not provide enough information, the articles were moved forward to the next step. Next, the research team worked in pairs and read full texts. Discrepancies about eligibility of studies were resolved within the pairs or if necessary discussed and decided on in the review team. Reasons for exclusion were noted. When the article selection process had been completed, the reference lists of the selected articles were searched for further studies meeting our inclusion criteria. The software tool Covidence (www. covidence.org) was used to facilitate the selection of abstracts and full-text articles.

Quality assessment

A quality assessment of the selected studies was also conducted in pairs. It was based on the Cochrane’s ‘Tool to Assess Risk of Bias in Cohort Studies’ (see methods.cochrane.org) which we modified to better correspond to the topic of this review. Eight dimensions were used: (1) How representative was the sample of the population under study?; (2) Can we be confident in the assessment of exposure?; (3) Can we be certain that the outcome was not present at start of study?; (4) Were all relevant confounders adjusted for in the analyses?; (5) Can we be confident in the assessment of confounders?; (6) Can we be confident in the assessment of outcome?; (7) Was the follow-up of cohorts adequate?; and (8) Were the statistical methods used adequate? Quality assessment scores ranged between 1 and 2 for the first dimension and between 1 and 4 for the following ones. Lower scores indicated higher quality. Ratings were first done individually by both researchers in the couple. The ratings were then discussed and agreed on within the couple. Disagreements were resolved in the full team. A total quality assessment score ranging between 8 and 30 was given each study. If several exposures or outcomes were measured in one study, each association was evaluated separately. We considered quality assessment scores 8–12 as indicating high quality, scores 13–16 indicating medium quality and scores 17–30 indicating low quality.

Synthesis of study results

Because there was a large heterogeneity in exposures, outcomes and types of effect estimates in the studies that met the inclusion criteria, it was not possible to conduct a meta-analysis. The analyses were divided according to exposure type into physical (physical violence and threats thereof), psychological (eg, bullying, harassment) or gender-based (violence towards people based on their gender, including sexual harassment) violence. We synthesised the evidence based on the quality and risk estimates of the included studies and considered the evidence as consistent if (1) several associations between a specific exposure and outcome (mental health, sickness absence or physical health) were similar with respect to direction, strength and statistical significance; and (2) most of these studies were assessed to be of at least medium quality.

Results

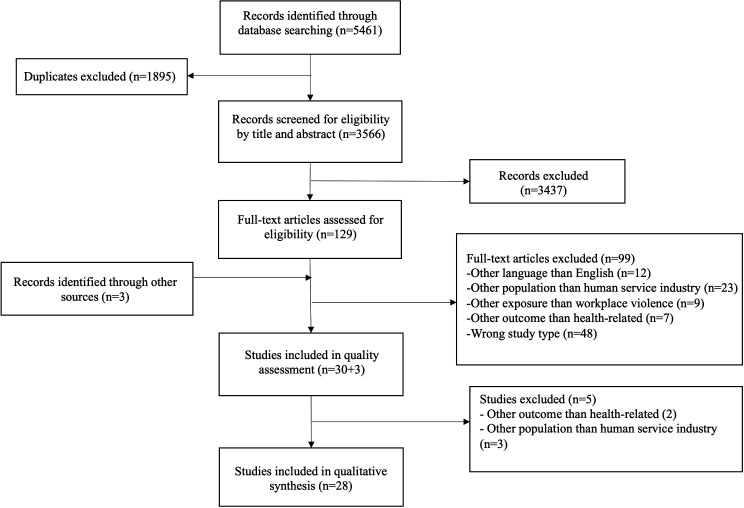

In the literature search, 5461 hits were recorded, of which 3566 remained after deduplication. Titles and abstracts of these articles were screened for eligibility, and 129 articles were selected for full-text screening. During full-text screening, additional 99 articles were excluded (primarily because of wrong study type or population) and 30 were passed on to the stage of quality assessment and synthesis. In the reference lists of our selected studies, additional three eligible articles were detected. During quality assessment, additional five studies were excluded because of wrong population (three) or outcome (two). Finally, 28 articles were included (see figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study selection.

Physical violence

Physical violence and mental health outcomes

As shown in table 1, we identified nine studies20–28 investigating associations between physical violence and mental health outcomes, of which two studies23 25 included two outcomes, respectively. Six studies20–22 24 27 28 were from the Nordic countries, two23 26 from other European countries and one25 from the USA. Five of them20 21 23–25 focused on healthcare personnel, three26–28 on employees within social care and one22 on teachers. One28 was given a high quality assessment, six20–23 25 27 were given medium quality assessments and two24 26 low quality assessments. Of the 11 effect estimates presented in the nine studies, 9 indicated statistically significant associations.

Table 1.

Included studies examining physical violence as a predictor of mental health outcomes, sickness absence and physical health outcomes in employees in health care, social care or education

| Author | Year | Country | Industry/ occupation | N (% women) | Exposure | Outcome | Covariates | Follow-up time | Statistical method | Risk estimate | Quality (score) | |

| Mental health outcomes | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Dement | 2014 | USA | Hospital employees | 9884 (not given) | Physical violence by patients, reported event | Psychotropic drug claims Days of drug supply |

Gender, age, race | 6 years | Multivariate Poisson regression analysis | Claim RR 1.45 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.33) Days of supply RR 1.33 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.87) |

M (15) |

| Mental health claims | Gender, age, race | 6 years | Multivariate Poisson regression analysis | n.s. | M (15) | |||||||

| 2 | Eriksen | 2006 | Norway | Nurses’ aids | 4076 (96.0) | Threats and violence, General Nordic Questionnaire for Psychological and Social Factors at Work (GPS-Nordic). Scale range from 1 ‘never or very seldom’ to 5 ‘very often or always’ |

Psychological distress (anxiety and depression) during the previous 14 days, Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-5). Scale range from 1 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘extremely’ | Work factors, change in work situation, age, gender, marital status, number of preschool children, pregnancy, care for relative, use of hypnotics, cigarette consumption, physical activity, chronic health problem, baseline psychological distress | 15 months | Multivariate linear regression analysis | b, unstandardised regression coefficient, 0.020, SE 0.007, p<0.01 | M (14) |

| 3 | Eriksen | 2008 | Norway | Nurses’ aids | 4771 (96.1) | Threats and violence, GPS-Nordic. Scale range from 1 ‘never or very seldom’ to 5 ‘very often or always’ |

Poor sleep during the previous 3 months, Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire. Scale range from 1 ‘well’ to 5 ‘badly’. Dichotomised, the worst three response alt indicating poor sleep | Age, gender, marital status, number of preschool children, care for relative, cigarette consumption, physical activity, long-term health problem, work schedule, physical work factors, several psychosocial work factors, use of hypnotics and sleep quality 3 months before baseline. | 3 months | Multivariate logistic regression analysis | Rather often: OR 1.77 (95% CI 1.27 to 2.46) Very often or always: OR 1.60 (95% CI 0.86 to 2.98) compared with never or very seldom |

M (14) |

| 4 | Gluschkoff | 2017 | Finland | Teachers | 4988 (77) | Threats and violence during the preceding year, ‘no’ or ‘yes’ | Disturbed sleep during the previous 4 weeks, Jenkins Sleep Problem Scale. Scale range from 1 ‘never’ to 6 ‘nearly every night’. Dichotomised with symptoms at least two to four times a week indicating disturbed sleep. | Age, gender | Three measures with 2-year intervals | Log-binomial regression analysis using generalised estimating equations | RR 1.26 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.48) | M (16) |

| 5 | Kind | 2018 | Switzerland | Caregivers (social education workers) in residential youth welfare institutions | 121 (62) | Verbal threats during the past 3 months, categorised into ‘verbal aggression’ vs ‘no aggression’ | Symptoms of burnout during the previous 3 weeks, Burnout Screening Scales, BOSS. Dichotomised, T-score ≥60. | Age, sex, work experience (years), employment in current institution (years), private stressors | 10.5 months (mean) | Cox proportional hazards analysis | HR 1.67 (95% CI 1.09 to 2.58) | L (17) |

| 6 | Magnavita | 2013 | Italy | Physicians, nurses and other hospital employees | 627 (57.3) | Physical aggression, Violent Incident Form, dichotomised (not described how) | Anxiety, Goldberg scales ranging 0 to 9, dichotomised with cut-point at 5 | Age, gender, job, department | 2 years | Logistic regression analysis | OR 5.00 (95% CI 2.27 to 11.0) | M (13) |

| Depression, Goldberg scales ranging 0 to 9, dichotomised with cut-point at 2 | Age, gender, job, department | Logistic regression analysis | OR 4.04 (95% CI 1.89 to 8.62) | M (13) | ||||||||

| 7 | Pihl-Thingvad | 2019 | Denmark | Social educators working with disabled adults | 1823 | Patient-initiated threats of physical violence, physical violence, severe assaults within the previous month, categorised into no, low and high exposure | Burnout symptoms, Copenhagen Burnout Inventory (CBI), 0=never to 4=always | Age, gender, somatic health, mental health, lifestyle factors, work-related factors, support, coping strategies | 1 year | Difference in burnout at baseline and follow-up measured with ANOVA, within and between subject design, general linear models for repeated measures | Low exposed 0.9 (0.3–2.6) High exposed 3.0 (0.5–3.5) Both exposed groups differ significantly from the non-exposed group |

H (12) |

| 8 | Pihl-Thingvad | 2019 | Denmark | Social educators working with disabled adults | 1763 | Patient-initiated threats of physical violence, physical violence, severe assaults within the previous month, frequency and severity | Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), The International Trauma Questionnaire, 0=non-clinical 1=subclinical and clinical PTSD |

Gender, age, BMI, alcohol, years of experience, critical incidents outside work, PTSD at baseline, trauma coping self-efficacy, workplace social capital, training, mutual adjustment frequency/severity | 1 year | Binary logistic regression |

Frequency

Low OR 4 (CI 1.0 to 16.3) Medium OR 5.9 (CI 1.4 to 24.2) High OR 6.5 (CI 1.6 to 25.6) Severity Mild violence OR 3.8 (CI 0.3 to 46.2) Threats OR 5.4 (CI 1.2 to 24.2) Moderate OR 2.6 (CI 0.6 to 10.8) Severe OR 6.5 (CI 1.6 to 26.0) |

M (13) |

| 9 | Sundin | 2011 | Sweden | Nurses | 775 (94.3) | Threats and violence, 3 items, ie, aggressive and threatening patients, being exposed to violence | Burnout, Maslach Burnout Inventory, emotional exhaustion and depersonalisation, both dimensions scored on a scale from 0 (never/low burnout) to 6 (every day/ high burnout score) and dichotomised according to normative values in a medical sample | Age, gender, marital status, number of years in profession, number of years in current work place | 1 year | Logistic regression analysis | n.s. | L (17) |

| Sickness absence | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Aagestad | 2014 | Norway | Health and social workers | 925 (100) | Threats and violence during the past 12 months, Statistics Norway, dichotomised ‘no’ or ‘yes’ | Doctor-certified sick leave 21 days or more | Age, educational level, occupation, chronic health complaint, disability, smoking, perceived mechanical workload, several work factors, sick leave at baseline | 1 year | Logistic regression analysis | n.s. | M (13) |

| 2 | Clausen | 2012 | Denmark | Employees in elder-care | 9520 (100) | Threats during the past 12 months. 1 ‘never exposed’, 2 ‘occasionally exposed’, 3 ‘frequently exposed’ |

Registerbased long-term sickness absence, 8 or more consecutive weeks | Age, job function, tenure, BMI, smoking status, psychosocial working conditions | 1 year | Cox proportional hazards analysis | HR 1.52* (95% CI 1.11 to 2.07) | M (14) |

| Violence during the past 12 months. 1 ‘never exposed’, 2 ‘occasionally exposed’, 3 ‘frequently exposed’ |

Register-based long-term sickness absence, 8 or more consecutive weeks | Age, job function, tenure, BMI, smoking status, psychosocial working conditions | 1 year | Cox proportional hazards analysis | HR 1.54 (95% CI 1.06 to 2.25) | M (14) | ||||||

| 3 | Rugulies | 2007 | Denmark | Human service workers (healthcare and social workers) | 890 (84) | Violence and threats of violence from clients during the past 12 months. Dichotomised into ‘no incidence’ and ‘at least one incidence’ | Self-reported days of sickness absence during the past 12 months | Age, gender, organisation, family status, children below the age of 7 at home, smoking, alcohol consumption, leisure time physical activity, BMI, socioeconomic status, baseline sickness absence | 3 years | Poisson regression analysis | RR 1.56 (95% CI 1.29 to 1.90) | M (15) |

| Physical health outcomes | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Camerino | 2008 | Eight European countries | Nurses | 34 107 (89.3) | Violence by patients/relatives, generally. Dichotomised into ‘no frequent violence’ and ‘frequent violence’ | Perceived health, SF-36. Scale range 1 ‘definitely false’ to 5 ‘definitely true’ | Country, gender, age, location of birth, occupational position, clinical setting, work shifts, work hours | 1 year | Hierarchical linear regression analysis | n.s. | M (16) |

| 2 | Miranda | 2014 | USA | Clinical staff in nursing homes | 344 (94) | Physical assault (in the past 3 months, having been hit, kicked, grabbed, shoved, pushed or scratched by a patient, patient’s visitor or family member while at work); analysed as (a) 0=no, 1=1–2 times, 2=3 or more times; (b) cumulative exposure over 2-year follow-up 1=none, 2=occasional, 3=frequent, 4=persistent | Musculoskeletal pain, self-reported wrt the preceding 3 months (a) in any of four specified body areas, (b) widespread pain, (c) pain intensity, (d) pain interfering with work, (e) pain interfering with sleep, (f) pain co-occurring with depressive symptoms | Age, gender, ethnic background, education, organisational unit, job demands, control, supervisor support, physically demanding, work–family interference | 2 years (three measurement points at 0, 12 and 24 months) | Log-binomial regression modelling | Physical assault at baseline increased the risk of all pain outcomes at 1-year follow-up, highest PR for widespread pain (PR 2.5 (95% CI 1.3 to 4.7) for 1–2 times and PR 2.4 (95% CI 1.3 to 4.4) for 3+ times compared with 0 times). Cumulative exposure to physical assault predicted most pain outcomes, highest PRs for widespread pain (PR 2.8 (95% CI 1.2 to 6.7) for occasional, PR 3.2 (95% CI 1.4 to 7.3) for frequent and PR 2.0 (95% CI 0.8 to 5.0) for persistent exposure to violence compared with none) |

M (14) |

*HRs of frequently exposed compared with never exposed.

ANOVA, analysis of variance; BMI, body mass index; L, low; M, medium; n.s., statistically non-significant; PR, prevalence ratio; Quality H, high; RR, rate ratio.

Physical violence and sickness absence

We identified three studies of medium quality from Denmark and Norway investigating associations between threats and physical violence and sickness absence in health and social workers.29–31 In one study,30 exposure to threats and violence were estimated separately, resulting in a total of four risk estimates. Two studies29 30 used register-based data on sickness absence and one31 self-reports; one29 did not find a statistically significant association between physical violence and sickness absence, whereas three studied associations were statistically significant.

Physical violence and physical health outcomes

Two studies were identified, one from the USA and one based on a sample from eight European countries, investigating other health and health-related outcomes among health and social workers.32 33 Both were assessed to be of medium quality. Results indicate a statistically significant association between physical violence and musculoskeletal pain,33 but not between physical violence and perceived health.32

Psychological violence

Psychological violence and mental health outcomes

As shown in table 2, we identified 10 studies of associations between psychological violence, primarily workplace bullying and poor mental health,20 21 23 34–40 of which 3 studies23 34 38 included two outcomes, respectively. All studies focused on employees within healthcare (nurses, physicians and care workers), and most of them were from Northern Europe. Two of the studies38 40 were given high quality assessments, seven20 21 23 34–37 medium quality and one39 a low quality assessment. Of the 13 risk estimates presented in the 10 studies, 11 showed statistically significant associations with poor mental health. There were two studies of the association with insomnia/poor sleep, of which the one of high quality40 showed that bullying predicted insomnia and the one of medium quality20 reported that exposure to bullying was associated with lower odds of sleep problems.

Table 2.

Included studies examining psychological violence as a predictor of mental health outcomes, sickness absence or physical health outcomes in employees in health care, social care or education

| Author | Year | Country | Industry/occupation | N (% Women) | Exposure | Outcome | Covariates | Follow-up time | Statistical methods | Risk estimate | Quality (score) | |

| Mental health outcomes | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Adriaenssens | 2015 | Belgium | Emergency nurses | 170 (54.7) | Social harassment, Leiden Quality of Work Questionnaire (LQWQ-N), Scale range 1 ‘totally disagree’ to 4 ‘totally agree’, a change score is used in which a higher score indicates a more favourable situation | Emotional exhaustion, Maslach Burnout Inventory, Scale range 0 ‘never’ to 6 ‘always’ | Age, gender, marital status, education, degree, years of service, working hours, shift work schedule | 18 months (mean) | Multiple linear regression analysis | β −0.14, p<0.05 | M (15) |

| Psychosomatic distress, sum score of symptoms of depression, anxiety and somatisation, Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI), Scale range 0 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘very much’ | Age, gender, marital status, education, years of service, working hours, shift work schedule. | 18 months (mean) | Multiple linear regression analysis | β −0.17, p<0.01 | M (15) | |||||||

| 2 | Eriksen | 2006 | Norway | Nurses’ aids | 4076 (96.0) | Bullying, GPS-Nordic, 0 ‘no’, 1 ‘yes’ | Psychological distress (anxiety and depression) during the previous 14 days, SCL-5. Scale range from 1 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘extremely’ | Work factors, change in work situation, age, gender, marital status, number of preschool children, pregnancy, care for relative, use of prescribed hypnotics, cigarette consumption, physical activity, chronic health problem, baseline psychological distress | 15 months | Multivariate linear regression analysis | n.s. | M (14) |

| 3 | Eriksen | 2008 | Norway | Nurses’ aids | 4771 (96.1) | Bullying, GPS-Nordic, 0 ‘no’, 1 ‘yes’ | Poor sleep, subjective sleep quality during the past 3 months, Basic Nordic Sleep Questionnaire, Scale range 1–5 with having slept ‘neither well not badly’ to ‘badly’ indicating poor sleep. | Age, gender, marital status, number of preschool children, care for relative, use of prescribed hypnotics, cigarette consumption, physical activity, chronic health problem | 3 months | Multivariate logistic regression analysis | OR 0.65 (95% CI 0.43 to 0.98) | M (14) |

| 4 | Kivimäki | 2003 | Finland | Hospital employees | 5432 (88.9) | Bullying, victims both surveys=‘bullied’, no bullying=‘not bullied’ | Depression, identified if respondent reported that a medical doctor had diagnosed him/her as having depression | Sex, age, occupation, income, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, job contract | 2 years | Logistic regression analysis | OR 4.2 (95% CI 2.0 to 8.6) | M (15) |

| 5 | Loerbroks | 2015 | Germany | Junior physicians | 507 (51.3) | Bullying, ‘no’ or ‘yes’ | Depressive symptoms, German Spielberger’s State-Trait Depression Scales, Scale range 1 ‘not at all’ to 4 ‘very much so’ | Age, sex, working hours, having a partner, alcohol consumption, physical activity, overweight/obesity, prevalent disease, and depression at baseline | 1 year, 3 years |

Linear regression analysis | 1-year follow-up: β 0.10, p=0.01 3-year follow-up: β 0.11, p=0.01 |

M (15) |

| 6 | Magnavita | 2013 | Italy | Physicians, nurses and other hospital employees | 627 (57.3) | Verbal (non-physical) aggression | Anxiety, Goldberg scales ranging from 0 to 9, dichotomised with cut-point at 5 | Age, gender, job, department | 2 years | Logistic regression analysis | OR 2.61 (95% CI 1.60 to 4.30) | M (13) |

| Depression, Goldberg scales ranging from 0 to 9, dichotomised with cut-point at 2 | Age, gender, job, department | 2 years | Logistic regression analysis | OR 2.66 (95% CI 1.61 to 4.39) | M (13) | |||||||

| 7 | Reknes | 2014 | Norway | Nurses | 1582 (90.2) | Bullying behaviours, measured by Negative Acts Questionnaire and analysed as a sum score ranging from 5 to 45 | Anxiety, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, range 0–21 | Age, gender, night work, job demands, symptoms at baseline | 1 year | Hierarchical regression analysis | β 0.06 (p<0.01) | H (12) |

| Depression, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale, range 0–21 | Age, gender, night work, job demands, symptoms at baseline | 1 year | Hierarchical regression analysis | n.s. | H (12) | |||||||

| 8 | Rugulies | 2012 | Denmark | Female elder-care workers | 5640 (100) | Bullying, participants were presented a definition of bullying and indicated how often they had been exposed during 12 last months, with five response options from ‘no’ to ‘yes, daily or almost daily’; recoded into (i) ‘no’, (ii) ‘occasional bullying’ (‘now and then’ and ‘monthly’), (iii) frequent bullying (‘weekly’ and ‘daily/almost daily’) | Major depression, Major Depression Inventory, sum score 0–50, dichotomised into major depression or not according to an algorithm in accordance with the criteria of DSM-IV | Age, cohabiting, type of job, and seniority, length of follow-up | 14–26 months, mean 20 months | Logistic regression | OR for onset of major depression: 2.12 (95% CI 1.29 to 3.48) for occasional bullying and 6.39 (95% CI 3.10 to 13.17) for frequent bullying compared with no bullying | M (14) |

| 9 | Trépanier | 2014 | Canada | Nurses | 508 (90.5) | Bullying, measured by Negative Acts Questionnaire, mean scores of three subscales (person-related, work-related and physical intimidation) used as indicators of latent variable | Burnout, mean scores of the emotional exhaustion and cynicism subscales of the Maslach Burnout Inventory were used as latent indicators of burnout | Gender, age, job position, working shift were considered; only job position was included (due to significant associations) | 1 year | Structural equation modelling | Work place bullying predicted burnout (β=0.25, p≤0.05) | L (17) |

| 10 | Vedaa | 2016 | Norway | Nurses | 799 (90) | Bullying, Negative Acts Questionnaire | Insomnia, Bergen Insomnia Scale, analysed as continuous variable | Manifest: night shifts, caffeine, cigarettes; Latent: morningness-eveningness, flexibility, languidity, sleepiness, alcohol, anxiety, depression, work–family spillover | 2 years | Structural equation modelling | (β=0.08, p<0.05) | H (11) |

| Sickness absence | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Aagestad | 2014 | Norway | Health and social workers | 925 (100) | Bullying, Statistics Norway, ‘no’ or ‘yes’ | Doctor-certified sick leave 21 days or more | Age, educational level, occupation, chronic health complaint, disability, smoking, perceived mechanical workload, several work factors | 1 year | Logistic regression analysis | OR 1.67 (95% CI 1.14 to 2.45) | M (13) |

| 2 | Clausen | 2012 | Denmark | Employees in elder-care | 9520 (100) | Bullying during the past 12 months, 1 ‘never’, 2 ‘occasionally’, 3 ‘frequently’ |

Register based long-term sickness absence, 8 or more consecutive weeks | Age, job function, tenure, BMI, smoking status, psychosocial working conditions | 1 year | Cox regression analysis | HR* 2.33 (95% CI 1.55 to 3.51) | M (14) |

| 3 | Kivimäki | 2000 | Finland | Hospital employees | 5655 (88.1) | Bullying, Statistics Finland, ‘yes’ or ‘no’ | Medically certified sickness absence, 4 days or more | Demographic data, occupational background, behaviour involving risks to health, baseline health status and sickness absence. | 1 year? | Poisson regression analysis | RR 1.26 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.44) | H (12) |

| Self-certified sickness absence, 3 days or fewer | Demographic data, occupational background, behaviour involving risks to health, baseline health status and sickness absence. | 1 year? | Poisson regression analysis | RR 1.16 (95% CI 1.05 to 1.29) | M (13) | |||||||

| 4 | Ortega | 2011 | Denmark | Elderly-care workers | 9749 (96.3) | Bullying, participants were presented a definition of bullying and indicated how often they had been exposed during 12 last months, categories (1) daily, (2) weekly, (3) monthly, (4) now and then, (5) never; recoded into (1) frequently (daily, weekly), (2) occasionally (monthly or less), (3) not bullied | Register-based long-term (>6 weeks) sickness absence, linkage to national register | Age, gender, occupational group, BMI, smoking habits, number of children at home, cohabiting status, psychosocial work factors | 1 year | Poisson regression analysis | RR 1.92 (95% CI 1.29 to 2.84) for frequently bullied, 1.11 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.41) for occasionally bullied compared with not bullied | M (13) |

| 5 | Roelen | 2018 | Norway | Nurses | 1533 (90) | Bullying behaviours, measured by Negative Acts Questionnaire and analysed as a sum score ranging from 5 to 45 (called it social harassment but other studies using the same instrument called it bullying behaviour) |

Register-based long-term sickness absence 17 days or more; all-cause and mental-health related | Age, sex, marital status, children at home, workplace setting, years registered as nurse, work hours/week | 2 years | Cox regression | HR 1.06 (95% CI 1.01 to 1.19) for mental health related long-term sickness absence and HR 1.06 (95% CI 1.02 to 1.11) for all-cause long-term sickness absence | H (12) |

| Physical health outcomes | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Camerino | 2008 | Eight European countries† | Nurses | 34 107 (89.3) | Harassment from superiors, the NEXT study group, Scale range 1 ‘never’ to 5 ‘daily’ | Perceived health, SF-36, Scale range 1 ‘definitely false’ to 5 ‘definitely true’, higher score indicates better health | Country, gender, age, location of birth, occupational position, clinical setting, work shifts, work hours | 1 year | Multiple linear regression analysis | n.s. | M (16) |

| Harassment from colleagues, the NEXT study group, Scale range 1 ‘never’ to 5 ‘daily’ | Perceived health, SF-36, Scale range 1 ‘definitely false’ to 5 ‘definitely true’, higher score indicates better health | Country, gender, age, location of birth, occupational position, clinical setting, work shifts, work hours | 1 year | Multiple linear regression analysis | β −0.02, p<0.05 | M (16) | ||||||

| 2 | Kivimäki | 2003 | Finland | Hospital employees | 5432 (88.9) | Bullying, victims both surveys=‘bullied’, no bullying=‘not bullied’ | Self-reported CVD, identified if respondent reported that a medical doctor had diagnosed him/her with myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, cerebrovascular disease or hypertension | Sex, age, occupation, income, BMI, smoking, alcohol consumption, job contract | 2 years | Logistic regression analysis | n.s. | M (15) |

| 3 | Kivimäki | 2004 | Finland | Hospital employees | 4791 (88.7) | Bullying, ‘currently bullied‘ or ‘not bullied’ | Self-reported fibromyalgia, identified if respondent reported that a medical doctor had diagnosed him/her with with fibromyalgia | Age, sex, income, obesity, smoking | 2 years | Logistic regression analysis | OR 4.1 (95% CI 2.0 to 9.6) | M (15) |

| 4 | Trépanier | 2016 | Canada | Nurses | 508 (90.5) | Bullying, measured by Negative Acts Questionnaire, mean scores of three subscales (person-related, work-related and physical intimidation) used as indicators of latent variable | Psychosomatic complaints, measured by eight items (eg, headaches, chest pains), analysed as a latent construct | Gender, age, job position, working shift tested; no sign diff and none included | 1 year | Structural equation modelling | n.s. | L (16) |

*HR frequently exposed, reference never exposed.

†Belgium, Germany, Finland, France, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia.

β, standardised regression coefficient; BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; Quality H, high; L, low; M, medium; n.s., statistically non-significant; RR, rate ratio.

Psychological violence and sickness absence

We identified five studies that investigated associations between workplace bullying and sickness absence,29 30 41–43 of which one41 studied associations with both medically and self-certified sickness absence. Sickness absence was in five of the six risk estimates based on register-data. The studies were all from the Nordic countries and focused on employees in health and social care. In total, four medium quality assessments, and two high quality assessments were given. All the six studied associations were statistically significant in the expected direction.

Psychological violence and physical health outcomes

Four studies were identified, one39 of low and three32 35 44 of medium quality, investigating effects of workplace bullying on self-reported cardiovascular disease,35 fibromyalgia,44 psychosomatic complaint39 and perceived health32 among healthcare workers. Workplace bullying predicted fibromyalgia but not cardiovascular disease in Finnish hospital employees, and social harassment did not predict psychosomatic complaints in Canadian nurses. In a study32 focusing nurses in eight European countries, harassment from colleagues but not from superiors was found to predict poorer perceived health.

Gender-based violence

As shown in table 3, we identified one Danish study, estimated to be of medium quality, that investigated effects of unwanted sexual attention on long-term sickness absence among care workers.30 No significant association was found.

Table 3.

Included studies examining gender-based and non-specific violence as predictors of mental health outcomes, sickness absence and physical health outcomes in employees in health care, social care or education

| Author | Year | Country | Industry/occupation | N (% Women) | Exposure | Outcome | Covariates | Follow-up time | Statistical method | Risk estimate | Quality (score) |

|

| Gender-based violence | ||||||||||||

| Sickness absence | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Clausen | 2012 | Denmark | Employees in elder-care | 9520 (100) | Unwanted sexual attention | Registerbased long-term sickness absence (8 or more consecutive weeks) | Age, job function, tenure, BMI, smoking status, psychosocial working conditions | HR 1.46 (95% CI 0.75 to 2.82) | M (14) | ||

| Non-specific violence | ||||||||||||

| Mental health outcomes | ||||||||||||

| 1 | De Loof | 2019 | The Netherlands | Mental health nurses | 110 (59) | Patient aggression, (verbal, physical, sexual), severity score calculated as the product of frequency and intensity | Burnout, Maslach Burnout Inventory, Sum score range from 3 ‘very low’ to 15 ‘very high’ | Job stress, emotional intelligence, neuroticism, altruism | 2 years (4 waves of data collection) |

Longitudinal multilevel model in which repeated measures were nested within individuals | Multilevel regression parameter 0.01, SE 0.00, p<0.05 | M (14) |

| Physical health outcomes | ||||||||||||

| 1 | Milner | 2017 | Australia | Medical doctors | 389 (39) | Workplace aggression from coworkers, patients, relatives, dichotomised (not described how) | Self-rated health, 5 categories (excellent, very good, good, fair, poor), dichotomised as good (excellent, very good) vs poor (the remaining categories) | Job demands, social support, job insecurity, job control, rewards at work, work–life imbalance, family restrictions, working hours, age, on call working hours, medical specialisation, partner/spouse, presence of children | 7 years (seven waves) | Fixed effects regression | n.s. | M (15) |

Effect estimate from the most well-adjusted model; Quality M=medium

BMI, body mass index; n.s., statistically non-significant.

Non-specific violence

As also shown in table 3, we found two articles that measured violence either without specification with regard to physical, psychological or gender-based violence,45 or studied violence as a composite measure of verbal, physical and sexual aggression.46 One Dutch study46 of mental health nurses found a statistically significant association between patient aggression and burnout symptoms, and one Australian study47 of medical doctors found no statistically significant association between workplace aggression from coworkers, patients or relatives and self-rated health. Both studies were found to be of medium quality.

Synthesis of study results

As shown in table 4, summarising data from all 28 studies and 44 risk estimates, prospective associations between physical and psychological violence, on the one hand, and mental health outcomes, on the other hand, have been rather extensively studied in human service professionals, particularly in employees in health and social care in the Nordic countries. A prospective association between physical violence and poor mental health was indicated by 9 of 11 risk estimates and an association between psychological violence (primarily bullying) and poor mental health by 10 of 13 risk estimates. Based on these findings of primarily medium quality studies, we consider that the evidence for an association between physical and psychological violence respectively and poor mental health is consistent. The association between physical and psychological violence, on the one hand, and sickness absence, on the other hand, has been less extensively studied. However, with statistically significant associations between psychological violence (bullying) and sickness absence found in six of six risk estimates in studies of medium to high quality, we consider the evidence to be consistent. Studies of medium quality furthermore indicate an association between physical violence and sickness absence among healthcare personnel in the Nordic countries, but to date we consider the evidence to be too limited to draw conclusions from. Finally, we consider the evidence to be insufficient regarding gender-based violence.

Table 4.

Summary of the included studies (n=28)

| Violence | Health outcome | No. of studies (No. of risk estimates) | Labour market sector | Country of origin | No. of risk estimates and statistical significance | Quality of study/risk estimate |

| Physical violence | Mental health outcomes | 9 (11) | 5 healthcare 3 social care 1 education |

6 Nordic countries two other European countries 1 USA |

9* 2 n.s. |

1 high 8 medium 2 low |

| Sickness absence | 3 (4) | Health and social care | Nordic countries | 3* 1 n.s. |

4 medium | |

| Physical health outcomes | 2 (2) | Healthcare | 1 Eight European countries 1 USA |

1* 1 n.s. |

2 medium | |

| Psychological violence | Mental health outcomes | 10 (13) | Healthcare | 6 Nordic countries 3 other European countries 1 Canada |

10* 1† 2 n.s. |

3 high 9 medium 1 low |

| Sickness absence | 5 (6) | Health and social care | Nordic countries | 6 * | 2 High 4 Medium |

|

| Physical health outcomes | 4 (5) | Healthcare | 2 Finland 1 eight European countries 1 Canada |

3* 2 n.s. |

1 Low 4 Medium |

|

| Gender-based violence | Mental health outcomes | – | – | – | – | – |

| Sickness absence | 1 (1) | Healthcare | Denmark | 1 n.s. | Medium | |

| Physical health outcomes | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Non-specific violence | Mental health outcomes | 1 (1) | Healthcare | The Netherlands | 1* | Medium |

| Sickness absence | – | – | – | – | – | |

| Physical health outcome | 1 (1) | Healthcare | Australia | 1 n.s. | Medium |

*Statistically significant in expected direction.

†Statistically significant in unexpected direction.

n.s., statistically non-significant.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of health consequences of workplace violence used by any perpetrator against employees in the female-dominated human service industries. We include a wide spectrum of health outcomes due to physical, psychological and gender-based violence, respectively, in studies with prospective or longitudinal study designs. We conclude that the evidence is consistent for an association between, on the one hand, physical and psychological violence and, on the other hand, negative mental health outcomes. The evidence is also consistent for an association between psychological violence and non-specific long-term sickness absence, and accumulating regarding an association between physical violence and non-specific long-term sickness absence. Various self-reported physical health outcomes have been studied in relation to physical and psychological violence, but more research is needed. Finally, there is insufficient evidence of prospective associations between gender-based violence and health outcomes.

Overall strengths of the evidence

Many studies of medium quality, using prospective study designs and large sample sizes, have investigated mental health effects of physical and psychological violence in the human service industries. In most of the studies, the design is well described and relevant confounders have been taken into account in many of them. Most studies have also ascertained that the outcome of interest was not present at baseline. In some studies, samples that were nationally representative of specific profession(s) were used. Frequency or severity of the exposure has been taken into account in some studies and some have used validated self-report instruments for measurement of exposure and outcome. The studies investigating associations with sickness absence have in most cases used register-based data and in one the sickness absence was specific by diagnosis.

Overall research gaps

There is a lack of prospective or longitudinal studies on health consequences of gender-based violence and a lack of research focusing the educational industry. Gender-based violence, such as sexual harassment, is known to be widespread in the human service industries, not least from patients in the health and social services.48 49 The only study on health effects of gender-based violence that we identified30 investigated the association between unwanted sexual attention and sickness absence. The exposure, which was not clearly defined, may be understood as relatively mild, while the length of the sickness absence, 8 or more consecutive weeks, indicates a rather severe illness. With regard to the educational industry, there is a large body of research on school social climate and bullying among pupils, in which teachers are regarded as resources to hinder negative acts. However, violence against the teachers themselves is also highly prevalent, at least in the Swedish educational system,50 51 and health consequences for the teachers need further attention.

Limitations in the current evidence

A clear limitation in the literature on health effects of workplace violence is the assessment of the exposure. The challenges of capturing the exposure to workplace violence and of refining these measures differ depending on type of violence. For example, physical violence has often been measured as a composite measure of threats of violence and actual physical violence. Furthermore, it is often not clear from the measure who exerts the violence, for example, patients, next-of-kin, collaborators or others. The severity, duration or frequency of the violence is also often unclear from the published studies. For psychological violence, such as bullying, there are other aspects to consider when it comes to measurement. The most common measure in the reviewed studies is the ‘self-labelling method’,52 meaning that the respondent is asked if he or she is currently or have over a defined period of time been exposed to bullying. This question is sometimes accompanied by a definition of bullying. Another, supposedly better method, is that the respondent is presented with a list of behaviours that indicate bullying and asked if he or she currently is or has been exposed to these behaviours, for example, the Negative Acts Questionnaire.53 A third method, not often used in the literature but suggested by Nielsen et al,52 used to measure to what extent an individual is exposed to behaviours that would indicate bullying, concerns the perspective of several individuals in the workgroup. Although the subjective perception of being bullied is crucial, we argue that it would strengthen the research field to complement this with other measures than the self-labelling one to get a broader picture of the exposure and its relation to outcomes. When it comes to gender-based violence, only one study met our inclusion criteria. General discussions in the research field of sexual and gender-based harassment is that questions of sexual harassment are often narrowly formulated, being close to the legal definition of the concept, and that because many people do not categorise exposures that they have experienced as the narrowly defined concept of sexual harassment, there is an under-reporting in the literature.2 The research on health effects of sexual and gender-based violence is still very limited. It is, however, reasonable to believe that some of the threats, physical and psychological violence reported in the current review are in fact gender based, although this has not been given enough attention in the studies. Future research should disentangle to what extent the victim perceives his or her gender or other personal characteristics to be a target for the violence.

Another clear limitation is the use of self-reported data on mental health outcomes. The measures are often not validated against diagnostic criteria. This limitation also concerns the physical health outcomes, which in the reviewed studies were all self-reported. In order to further strengthen the evidence regarding health effects of workplace violence, more outcome measures based on register data on diagnoses are needed. Most data on sickness absence were based on registries, in most cases however with the limitation of being non-specific.

Another limitation is that the time between exposure assessment and the outcome measurement is not motivated and shows considerable variation between the studies. One example is the timeframe for retrospective self-labelling–how long back is such a measurement reliable or relevant? It is furthermore not theoretically outlined in the included studies how long it may take for various negative health outcomes to develop in response to exposure to the various forms of workplace violence.

Our overall conclusion is that the evidence is consistent regarding an association between psychological violence and poor mental health in human service workers. However, it should be noted that some of the risk estimates were high and the CIs were rather wide, indicating poor precision. There are also studies that do not find an association between psychological violence and mental ill-health. One study of medium quality20 furthermore reported the unexpected finding that exposure to bullying was associated with lower odds of sleep problems. The authors of the study suggest selection mechanisms to explain the finding, that is, that employees remaining in a work situation in which they are being bullied may be more resilient, and also have fewer symptoms of poor sleep, than others. The variations across studies may partly be due to uncertainty in the exposure assessment, different time perspectives and self-reported outcome measures that have not been validated against diagnostic criteria, as discussed previously. Poor statistical power for some groups is another possible explanation. In the studies assessed to be of high quality, statistically significant associations between psychological violence and poor mental health were found in two of three studies (66.7 %), and in the studies of medium quality, the corresponding number was seven of nine (77.8 %), suggesting that more studies of high quality are needed before firm conclusions about prospective associations can be drawn.

Other limitations to consider is that most of the studies included in the present review are prospective, with data on the exposure available only at baseline, and caution needs to be taken regarding conclusions about causality. More longitudinal studies, measuring both exposure and outcome at two or several time points, in which reverse causality can be taken into account, are needed to strengthen the evidence. Intervention studies targeting exposure to workplace violence with evaluation of possible changes in health have, to the best of our knowledge, not been conducted and would add to the current state of evidence. For example, clear and well-communicated workplace policies regarding how incidents of violence should be handled, and better training among staff in handling incidents could lead to a greater sense of preparedness and control, which in turn could moderate the negative impact of violence among staff. Furthermore, even if many of the reviewed studies included several relevant confounders in the analyses, few studies applied statistical methods that take into account unmeasured confounding, such as personality. Another limitation is that convenience samples were used in most studies, with consequences for generalisability to the study population.

Strengths and limitations of the current review

Strengths of the present review include the focus on the human service industries that are highly exposed to workplace violence, a distinction between different forms of workplace violence, the inclusion of a broad spectrum of health outcomes and the inclusion of only prospective or longitudinal studies. Through the assessment of the quality of evidence, we identified methodological strengths and limitations in the current best quality studies and pointed out factors that could improve the evidence even further.

There are, however, also several limitations. After the literature searches had been finalised, we detected an additional three eligible articles when checking reference lists in our selected studies. They were most likely not detected in the primary search because several work exposures were measured, and violence may not have appeared clearly in the text that was searched. We cannot rule out that other studies were missed for the same reason. Furthermore, if the occupational groups were not clearly stated, but only included in sensitivity analyses or the like, such associations may have been missed in the current review. We cannot rule out the risk of publication bias. Also, due to the low number of studies, we categorised the health outcomes into broad groups. For example, physical health outcomes include a wide range of outcomes with possibly very different underlying mechanisms. Perceived general health furthermore does not only cover perceived physical but also psychological health. This all means that while broad, the health outcomes are also unspecific. Also, much of the evidence derived from the developed world (primarily the Nordic European countries) and generalisability could be limited. The overall aim of the present review was to highlight potential health effects of various forms of workplace violence in the human service industries. We therefore included a large variety of workplace violence types and health outcomes, but on the other hand a restricted population. Although it is often recommended to conduct meta-analyses to summarise results, as stated in the protocol registered in PROSPERO, it was never intended here. We believe a meta-analysis would have been of limited added value due to large heterogeneity of the exposure and health outcomes.54–56 Instead, we presented the results carefully and transparently in several exhaustive tables.54

Implications for future research

There is a general need to clarify concepts of workplace violence, to better distinguish between different types of violence and to improve exposure assessment. Theories regarding how different forms of workplace violence may impact employee health over time should be developed and empirically tested, with adequate timeframes taken into account. Other aspects that would move the research field forward is the use of register-based diagnoses of disease as outcome, representative samples and the application of statistical methods that take unmeasured confounding such as personality into account.

Conclusion

There is consistent evidence mainly in medium quality studies of prospective associations between psychological violence and poor mental health and sickness absence, and between physical violence and poor mental health in human service workers. More research using objective outcomes, improved exposure assessment and that focus on gender-based violence is needed.

Practical implications

It is stated in the ILO convention4 and recommendation57 that everyone has the right to a working life free from workplace violence and that member states should adopt appropriate measures of prevention in sectors that are more exposed. The evidence of the present review supports the need to develop guidelines for readily detecting and dealing with workplace violence in the human service industries.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Sabina Gillsund and Susanne Gustafsson at the Karolinska University Library in Stockholm for their professional support in developing the search strategy, conducting the database searches and delivering the selected studies to the review team. We would also like to thank Tom Sterud at the National Institute of Occupational Health (STAMI) in Oslo, Norway, for valuable comments that improved this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AN was the principal investigator of the study, responsible for and main contributor to all phases of the study: development of search strategy, study selection, quality assessment, data synthesis and the writing of the article. GK took part in all phases of the study and contributed specifically with expertise on systematic review methodology and more generally with overall knowledge and experience. LMH took part of all phases of the study and contributed specifically with methodological expertise and expertise on workplace violence. KR took part in all phases of the study, was very active in the selection and quality assessment phases, contributed with methodological expertise, and read and commented on early drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Swedish Research Council for health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE), #2018-00016.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Guay S, Goncalves J, Jarvis J. A systematic review of exposure to physical violence across occupational domains according to victims' sex. Aggress Violent Behav 2015;25:133–41. 10.1016/j.avb.2015.07.013 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McDonald P Workplace sexual harassment 30 years on: a review of the literature. Int J Manag Rev 2012;14:1–17. 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00300.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nielsen MB, Matthiesen SB, Einarsen S. The impact of methodological moderators on prevalence rates of workplace bullying. A meta-analysis. J Occup Organ Psychol 2010;83:955–79. 10.1348/096317909X481256 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. International Labour Conference Convention 190. convention concerning the elimination of violence and harassment in the world of work. Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pompeii L, Dement J, Schoenfisch A, et al. Perpetrator, worker and workplace characteristics associated with patient and visitor perpetrated violence (type II) on hospital workers: a review of the literature and existing occupational injury data. J Safety Res 2013;44:57–64. 10.1016/j.jsr.2012.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hahn S, Zeller A, Needham I, et al. Patient and visitor violence in general hospitals: a systematic review of the literature. Aggress Violent Behav 2008;13:431–41. 10.1016/j.avb.2008.07.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piquero NL, Piquero AR, Craig JM, et al. Assessing research on workplace violence, 2000–2012. Aggress Violent Behav 2013;18:383–94. 10.1016/j.avb.2013.03.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu J, Gan Y, Jiang H, et al. Prevalence of workplace violence against healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med 2019;76:927–37. 10.1136/oemed-2019-105849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Swedish social insurance Agency. sick leave at the Swedish labour market. Sick leave longer than 14 days and termination of sick leave within 180 days by indutry and occupation, Stockholm 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Aagestad C, Tyssen R, Sterud T. Do work-related factors contribute to differences in doctor-certified sick leave? A prospective study comparing women in health and social occupations with women in the general working population. BMC Public Health 2016;16:235. 10.1186/s12889-016-2908-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buscariolli A, Kouvonen A, Kokkinen L, et al. Human service work, gender and antidepressant use: a nationwide register-based 19-year follow-up of 752 683 women and men. Occup Environ Med 2018;75:401–6. 10.1136/oemed-2017-104803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wieclaw J, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB, et al. Risk of affective and stress related disorders among employees in human service professions. Occup Environ Med 2006;63:314–9. 10.1136/oem.2004.019398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Madsen IEH, Diderichsen F, Burr H, et al. Person-related work and incident use of antidepressants: relations and mediating factors from the Danish work environment cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010;36:435–44. 10.5271/sjweh.3049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Aronsson V, Toivanen S, Leineweber C, et al. Can a poor psychosocial work environment and insufficient organizational resources explain the higher risk of ill-health and sickness absence in human service occupations? Evidence from a Swedish national cohort. Scand J Public Health 2019;47:310–7. 10.1177/1403494818812638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Konttila J, Pesonen H-M, Kyngäs H. Violence committed against nursing staff by patients in psychiatric outpatient settings. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2018;27:1592–605. 10.1111/inm.12478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lanctôt N, Guay S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: a systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggress Violent Behav 2014;19:492–501. 10.1016/j.avb.2014.07.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nikathil S, Olaussen A, Gocentas RA, et al. Review article: workplace violence in the emergency department: a systematic review and meta analysis. Emerg Med Australas 2017;29:265–75. 10.1111/1742-6723.12761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Scott A, Ryan A, James I, et al. Perceptions and implications of violence from care home residents with dementia: a review and commentary. Int J Older People Nurs 2011;6:110–22. 10.1111/j.1748-3743.2010.00226.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Henning MA, Zhou C, Adams P, et al. Workplace harassment among staff in higher education: a systematic review. Asia Pacific Educ. Rev. 2017;18:521–39. 10.1007/s12564-017-9499-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Eriksen W, Bjorvatn B, Bruusgaard D, et al. Work factors as predictors of poor sleep in nurses' aides. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2008;81:301–10. 10.1007/s00420-007-0214-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Eriksen W, Tambs K, Knardahl S. Work factors and psychological distress in nurses' aides: a prospective cohort study. BMC Public Health 2006;6:290. 10.1186/1471-2458-6-290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gluschkoff K, Elovainio M, Hintsa T, et al. Organisational justice protects against the negative effect of workplace violence on teachers' sleep: a longitudinal cohort study. Occup Environ Med 2017;74:511–6. 10.1136/oemed-2016-104027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Magnavita N The exploding spark: workplace violence in an infectious disease Hospital—A longitudinal study. Biomed Res Int 2013;2013:1–9. 10.1155/2013/316358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sundin L, Hochwälder J, Lisspers J. A longitudinal examination of generic and occupational specific job demands, and work-related social support associated with burnout among nurses in Sweden. Work 2011;38:389–400. 10.3233/WOR-2011-1142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dement JM, Lipscomb HJ, Schoenfisch AL, et al. Impact of hospital type II violent events: use of psychotropic drugs and mental health services. Am J Ind Med 2014;57:627–39. 10.1002/ajim.22306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kind N, Eckert A, Steinlin C, et al. Verbal and physical client aggression - A longitudinal analysis of professional caregivers' psychophysiological stress response and burnout. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2018;94:11–16. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pihl-Thingvad J, Andersen LL, Brandt LPA, et al. Are frequency and severity of workplace violence etiologic factors of posttraumatic stress disorder? A 1-year prospective study of 1,763 social educators. J Occup Health Psychol 2019;24:543–55. 10.1037/ocp0000148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pihl-Thingvad J, Elklit A, Brandt LPA, et al. Workplace violence and development of burnout symptoms: a prospective cohort study on 1823 social educators. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2019;92:843–53. 10.1007/s00420-019-01424-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Aagestad C, Tyssen R, Johannessen HA, et al. Psychosocial and organizational risk factors for doctor-certified sick leave: a prospective study of female health and social workers in Norway. BMC Public Health 2014;14:1016. 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Clausen T, Hogh A, Borg V. Acts of offensive behaviour and risk of long-term sickness absence in the Danish elder-care services: a prospective analysis of register-based outcomes. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2012;85:381–7. 10.1007/s00420-011-0680-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rugulies R, Christensen KB, Borritz M, et al. The contribution of the psychosocial work environment to sickness absence in human service workers: results of a 3-year follow-up study. Work Stress 2007;21:293–311. 10.1080/02678370701747549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Camerino D, Estryn-Behar M, Conway PM, et al. Work-Related factors and violence among nursing staff in the European next study: a longitudinal cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:35–50. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Miranda H, Punnett L, Gore RJ, et al. Musculoskeletal pain and reported workplace assault: a prospective study of clinical staff in nursing homes. Hum Factors 2014;56:215–27. 10.1177/0018720813508778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Adriaenssens J, De Gucht V, Maes S. Causes and consequences of occupational stress in emergency nurses, a longitudinal study. J Nurs Manag 2015;23:346–58. 10.1111/jonm.12138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kivimäki M, Virtanen M, Vartia M, et al. Workplace bullying and the risk of cardiovascular disease and depression. Occup Environ Med 2003;60:779–83. 10.1136/oem.60.10.779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Loerbroks A, Weigl M, Li J, et al. Workplace bullying and depressive symptoms: a prospective study among junior physicians in Germany. J Psychosom Res 2015;78:168–72. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rugulies R, Madsen IEH, Hjarsbech PU, et al. Bullying at work and onset of a major depressive episode among Danish female eldercare workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 2012;38:218–27. 10.5271/sjweh.3278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Reknes I, Pallesen S, Magerøy N, et al. Exposure to bullying behaviors as a predictor of mental health problems among Norwegian nurses: results from the prospective SUSSH-survey. Int J Nurs Stud 2014;51:479–87. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.06.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Trépanier S-G, Fernet C, Austin S. Longitudinal relationships between workplace bullying, basic psychological needs, and employee functioning: a simultaneous investigation of psychological need satisfaction and frustration. Eur J Work Organizatio Psychol 2016;25:690–706. 10.1080/1359432X.2015.1132200 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vedaa Øystein, Krossbakken E, Grimsrud ID, et al. Prospective study of predictors and consequences of insomnia: personality, lifestyle, mental health, and work-related stressors. Sleep Med 2016;20:51–8. 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kivimäki M, Elovainio M, Vahtera J. Workplace bullying and sickness absence in hospital staff. Occup Environ Med 2000;57:656–60. 10.1136/oem.57.10.656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ortega A, Christensen KB, Hogh A, et al. One-Year prospective study on the effect of workplace bullying on long-term sickness absence. J Nurs Manag 2011;19:752–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01179.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Roelen CAM, van Hoffen MFA, Waage S, et al. Psychosocial work environment and mental health-related long-term sickness absence among nurses. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2018;91:195–203. 10.1007/s00420-017-1268-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kivimäki M, Leino-Arjas P, Virtanen M, et al. Work stress and incidence of newly diagnosed fibromyalgia: prospective cohort study. J Psychosom Res 2004;57:417–22. 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2003.10.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Milczarek M, Schneider E, Rial González E. OSH in figures: Stress at work - facts and figures. Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 46. de Looff P, Didden R, Embregts P, et al. Burnout symptoms in forensic mental health nurses: results from a longitudinal study. Int J Ment Health Nurs 2019;28:306–17. 10.1111/inm.12536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Milner A, Witt K, Spittal MJ, et al. The relationship between working conditions and self-rated health among medical doctors: evidence from seven waves of the medicine in Australia balancing employment and life (MABEL) survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17:609. 10.1186/s12913-017-2554-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Friborg MK, Hansen JV, Aldrich PT, et al. Workplace sexual harassment and depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional multilevel analysis comparing harassment from clients or customers to harassment from other employees amongst 7603 Danish employees from 1041 organizations. BMC Public Health 2017;17:675. 10.1186/s12889-017-4669-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Nielsen MBD, Kjær S, Aldrich PT, et al. Sexual harassment in care work - Dilemmas and consequences: A qualitative investigation. Int J Nurs Stud 2017;70:122–30. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Göransson S, Knight R, Guthenberg J, et al. Hot och våld i skolan - en enkätstudie bland lärare och elever. Rapport 2011:15. Stockholm 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rask L, Jondell Assbring M, Mörtlund T. Attityder till skolan 2018. Rapport 479 2019. Stockholm 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Nielsen MB, Einarsen SV. What we know, what we do not know, and what we should and could have known about workplace bullying: an overview of the literature and agenda for future research. Aggress Violent Behav 2018;42:71–83. 10.1016/j.avb.2018.06.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Einarsen S, Hoel H, Notelaers G. Measuring exposure to bullying and harassment at work: validity, factor structure and psychometric properties of the negative acts Questionnaire-Revised. Work & Stress 2009;23:24–44. 10.1080/02678370902815673 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Valentine JC, Pigott TD, Rothstein HR. How many studies do you need? A primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. J Educ Behav Stat 2010;35:215–47. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Greco T, Zangrillo A, Biondi-Zoccai G, et al. Meta-Analysis: pitfalls and hints. Heart Lung Vessel 2013;5:219–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van Wely M The good, the bad and the ugly: meta-analyses. Hum Reprod 2014;29:1622–6. 10.1093/humrep/deu127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. International Labour Conference Recommendation 206. recommendation concerning the elimination of violence and harassment in the world of work. Geneva, 2019. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

oemed-2020-106450supp001.pdf (21.7KB, pdf)