Message

Disconnected pancreatic duct (DPD) is a frequent occurrence in cases with walled-off necrosis (WON). The impact of DPD on recurrence of collection after removal of metal stents is not clear. Also, association between DPD and new-onset diabetes mellitus (DM) is not well known. In a large cohort of patients with WON, we observed DPD in majority (3/4th) of the cases. The presence of DPD was a significant risk factor for the recurrence of fluid collections as well as new-onset DM. However, the incidence of recurrent fluid collections and the requirement of reintervention was low (<10%).

In more detail

Background

DPD is defined as complete disruption of PD with isolation of viable portion of upstream pancreas.1 DPD may be associated with recurrent pancreatic fluid collections (PFC) and predispose these patients to new-onset DM.2–7 In addition, the strategies to prevent recurrences of PFCs are unclear. The limitations of existing literature include small sample size, short follow-up periods and lack of objective evaluation. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the impact of DPD on the recurrence of PFC and the development of new-onset DM in subjects who underwent drainage of WON using large calibre metal stents (LCMS).

Methods

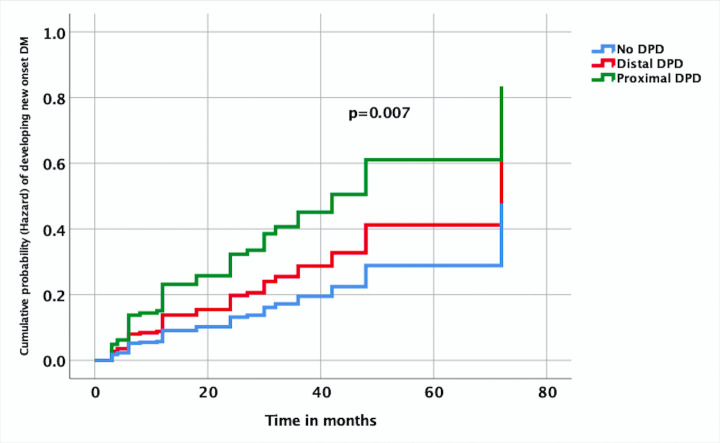

The data of subjects with WON who underwent endoscopic ultrasound (EUS)-guided drainage using LCMS between January 2013 and June 2017 were analysed from a prospectively maintained database. EUS-guided drainage was performed using LCMS (Nagi; Taewoong Medical, Gyeonggido, South Korea) as per the standard technique.8 Approximately 4–8 weeks after drainage, imaging (MRI with MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP)) was performed to establish the resolution of WON and delineate PD (figure 1). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was performed in all the cases to confirm the findings on MRCP and place a PD stent in cases with leak or stricture (figure 2). LCMSs were removed regardless of the presence or absence of DPD. After removal of LCMS, follow-up was performed every 3 months for 1.5 years thereafter. The patients were evaluated for recurrence of PFC and new-onset DM during the follow-up visits.

Figure 1.

Flow chart showing schematic presentation of study design. DPD, disconnected pancreatic duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; EUS, endoscopic ultrasound; MRCP, MR cholangiopancreatography; PD, pancreatic duct; WON, walled-off necrosis.

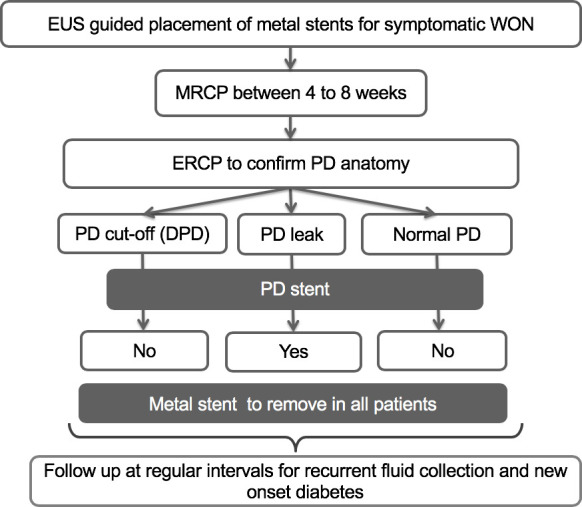

Figure 2.

Disconnected pancreatic duct images (A): MRCP showing non-projection of main pancreatic duct in body region with dilated upstream pancreatic duct suggestive of DPD, (B): ERCP showing normal diameter pancreatic duct in head, with cut-off at genu and non-visualisation of upstream duct suggestive of DPD, (C): ERCP showing normal diameter pancreatic duct in head and proximal body with cut-off at distal body and non visualisation of upstream duct suggestive of DPD. DPD, disconnected pancreatic duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP, MR cholangiopancreatography.

Results

A total of 274 subjects (males 236; median age 32 years) underwent drainage of WON during the study period. The demographic characteristics, aetiology, adverse events and rates of reintervention have been outlined in table 1. Two hundred and fifty-six (93.4%) patients underwent ERCP prior to removal of LCMS. PD abnormalities were detected in 219 subjects, including DPD (189, 73.8%), PD leak (19, 7.4%), stricture (9, 3.5%) and dilated PD with calculi (2, 0.8%). A transpapillary stent was placed in 30 (12.5%) cases with PD leak, stricture and intraductal calculi (figure 2). The median follow-up was 30 months (range: 12–72 months). Recurrent PFC developed in 34 out of 256 subjects (13.2%) at a median follow-up of 5 months (range: 1–19). Majority (97%) of the cases who developed recurrent PFC had DPD. The risk of recurrent PFC was significantly higher in cases with DPD (17.4% vs 1.5%, p<0.001 OR 13.6, 95% CI 1.8 to 102). Reinterventions were required in 17 (6.6%) cases with symptomatic recurrences.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics and study details

| Study characteristics | No of subjects |

| Total no of subjects | 274 |

| Age in years, median (range) | 32 years (9 – 65) |

| Sex (male:female) | 236:38 |

| Aetiology of pancreatitis | |

| Ethanol | 104 (38%) |

| Idiopathic | 98 (35.7%) |

| Gall stones | 61 (22.2%) |

| Others | 11 (4%) |

| Size of WON, mean±SD (cm) | 11.6±3.2 |

| Complications | 10 (3.6%) |

| Reintervention required | 75 (27.3%) |

| Imaging for PD anatomy | |

| MRCP | 255 |

| ERCP | 256 (successful in—239) |

| PD anatomy | |

| Normal PD | 37 (14.4%) |

| DPD | 189 (73.8) |

| PD leak | 19 (7.4) |

| PD stricture | 9 (3.5%) |

| Dilated PD with calculi | 2 (0.8%) |

| Location of DPD | |

| Head | 29 (15.3%) |

| Genu | 60 (31.7%) |

| Body | 86 (45.5%) |

| Tail | 14 (7.4%) |

| Follow in months, median (range) | 30 (12–72) |

DPD, disconnected pancreatic duct; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MRCP, MR cholangiopancreatography; PD, pancreatic duct.

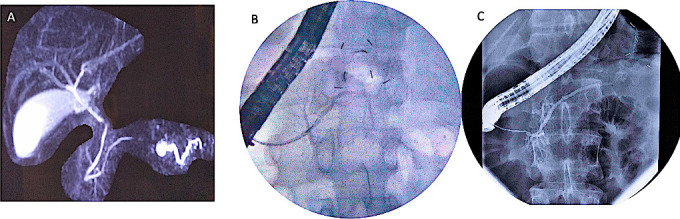

New-onset DM was detected in 59 out of 213 subjects (27.7%) at a median follow-up of 24 months (range: 2–72). The occurrence of DM was significantly higher in those with DPD (31.4% vs 16.6%, p=0.036, OR 2.29, 95% CI 1.04 to 5.05). Moreover, the risk is more with proximal (head, genu) DPD (39.2%) when compared with distal (body, tail) DPD (23.7%). On Cox proportional hazard model, the occurrence of DM with time was significantly high in proximal DPD (HR −2.767, 95% CI −1.317 to 5.817, p=0.007) compared with subjects without DPD (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Time to event analysis based on Cox proportional hazard model showing cumulative probability (hazard function) of developing new-onset diabetes mellitus (DM) over time in different pancreatic duct (PD) anatomies (disconnected PD (DPD), proximal DPD—at head or genu of pancreas, distal DPD—at body and tail of pancreas. Proximal DPD, HR −2.767, 95% CI −1.317 to 5.817, p=0.007), distal DPD, (HR −1.561, 95% CI −0.704 to 3.459, p=0.273) with no DPD as reference).

Comment

In this study, DPD was frequent among subjects who underwent drainage of WON using LCMS. The presence of DPD was associated with the recurrence of PFC and development of new-onset DM. However, the overall incidence of recurrent PFC and the requirement of re-intervention was low. WON is frequently accompanied by DPD, the clinical significance of which remains to be seen. A high incidence of DPD (74%) in our study stands in concordance with previous studies where DPD has been noticed in 53%–79%.2 3 5 9 While DPD was found in 3/4th of the study cohort, the recurrence of PFC was noticed in a minority (13%) of subjects. Nearly all the recurrences were noticed in cases with DPD. In cases with recurrent PFC, half were asymptomatic and did not require reintervention. In contrast, a relatively high (up to 50%) incidence of recurrence of PFC has been reported in in the published studies.3–5 10 The main drawbacks of the previously published studies include small sample size with short follow-up and heterogenous study population. Whereas, the present study comprised of a large cohort of homogenous subjects with WON.

The second objective was to evaluate the influence of DPD on new-onset DM. Acute pancreatitis is a known risk factor for new-onset DM and the risk correlates with extent of pancreatic necrosis.11–16 In subjects with necrotising pancreatitis, whether DPD contributes to the development of new-onset DM is not known. We observed new-onset DM in 31.4% of subjects with DPD. In contrast, new-onset DM was found in only 16.6% of subjects without DPD. We hypothesise that atrophy of upstream pancreas over time due to ductal hypertension in the disconnected segment of PD may account for the higher occurrence of new-onset DM in this group. Two observations support this hypothesis. First, the disconnected segment of PD is often dilated as visualised on MRCP suggesting ductal hypertension (figure 2A). Second, DM was significantly more in subjects with proximal disconnection than distal disconnection, which suggests that a larger volume of pancreas is at risk of atrophy with proximal disconnection. However, this hypothesis needs to be evaluated in future studies. This finding may pave way for future trials to see if new-onset DM can be prevented by draining the upstream disconnected PD.

There are several implications of the results in our study. First, the risk of recurrence is negligible in the absence of DPD. Therefore, this subset of patients do not require frequent monitoring for recurrence of PFC. Second, about half of the recurrences are asymptomatic and can be managed conservatively. Our results also challenge the practice of keeping the plastic stents in situ indefinitely or exchanging metal with plastic stents in order to prevent recurrence of PFC. The incidence of symptomatic recurrences of PFC after index drainage procedure is too low to justify this practice. Moreover, it may be especially difficult to place plastic stents in a collapsed cavity after the resolution of WON. A logical and simplistic approach would be to treat small number of symptomatic recurrences as and when required. However, prospective randomised trials are required to confirm our findings.

The strengths of our study include—large and homogeneous study population who underwent drainage exclusively with metal stents, evaluation of data from a prospectively maintained database, and systematic evaluation of pancreatic ductal anatomy at a predefined interval. However, few drawbacks are noteworthy. The foremost is the retrospective nature of the study from a single centre. We evaluated the integrity of PD using two modalities, that is, MRCP followed by ERCP due to non-availability of secretin in our country. ERCP may not be required in cases with unequivocal findings on MRCP. Although, the risk of symptomatic recurrence of PFC was low in cases with DPD prospective trials with long-term follow-up are required to confirm our results.

To conclude, DPD is frequently observed (3/4th) in subjects with WON after removal of LCMS. The presence of DPD was a risk factor for the recurrence of fluid collections. However, the overall occurrence of recurrent PFC is less and only few of them requires an intervention. DPD was also a significant risk factor for the development of new-onset DM, with higher risk in proximal disconnection. Future studies are warranted to devise strategies for the prevention of new-onset DM in these subjects.

Footnotes

Twitter: @drkalpala

Contributors: JB: EUS and endoscopic intervention, data collection and manuscript draft. SL: EUS and endoscopic intervention, data collection and manuscript draft. ZN: EUS and endoscopic intervention, manuscript review. PP: data collection statistical inputs. RC: manuscript review. RT: manuscript review, statistical inputs. MR: EUS and endoscopic intervention, manuscript review. RG: EUS and endoscopic intervention, manuscript review. RK: EUS and endoscopic intervention, manuscript review. GVR: surgical intervention, intellectual inputs. DNR: manuscript review and intellectual inputs.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Kozarek RA, Ball TJ, Patterson DJ, et al. Endoscopic transpapillary therapy for disrupted pancreatic duct and peripancreatic fluid collections. Gastroenterology 1991;100:1362–70. 10.1016/0016-5085(91)70025-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Varadarajulu S, Wilcox CM. Endoscopic placement of permanent indwelling transmural stents in disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome: does benefit outweigh the risks? Gastrointest Endosc 2011;74:1408–12. 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dhir V, Adler DG, Dalal A, et al. Early removal of biflanged metal stents in the management of pancreatic walled-off necrosis: a prospective study. Endoscopy 2018;50:597–605. 10.1055/s-0043-123575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bang JY, Wilcox CM, Trevino J, et al. Factors impacting treatment outcomes in the endoscopic management of walled-off pancreatic necrosis. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2013;28:1725–32. 10.1111/jgh.12328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bang JY, Wilcox CM, Navaneethan U, et al. Impact of disconnected pancreatic duct syndrome on the endoscopic management of pancreatic fluid collections. Ann Surg 2018;267:561–8. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arvanitakis M, Delhaye M, Bali MA, et al. Pancreatic-fluid collections: a randomized controlled trial regarding stent removal after endoscopic transmural drainage. Gastrointest Endosc 2007;65:609–19. 10.1016/j.gie.2006.06.083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bang JY, Hasan M, Navaneethan U, et al. Lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS) for pancreatic fluid collection (pFc) drainage: may not be business as usual. Gut 2017;66:2054–6. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lakhtakia S, Basha J, Talukdar R, et al. Endoscopic “step-up approach” using a dedicated biflanged metal stent reduces the need for direct necrosectomy in walled-off necrosis (with videos). Gastrointest Endosc 2017;85:1243–52. 10.1016/j.gie.2016.10.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Varadarajulu S, Rana SS, Bhasin DK. Endoscopic therapy for pancreatic duct leaks and disruptions. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am 2013;23:863–92. 10.1016/j.giec.2013.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Puli SR, Graumlich JF, Pamulaparthy SR, et al. Endoscopic transmural necrosectomy for walled-off pancreatic necrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2014;28:50–3. 10.1155/2014/539783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tu J, Yang Y, Zhang J, et al. Effect of the disease severity on the risk of developing new-onset diabetes after acute pancreatitis. Medicine 2018;97:e10713. 10.1097/MD.0000000000010713 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Das SLM, Kennedy JIC, Murphy R, et al. Relationship between the exocrine and endocrine pancreas after acute pancreatitis. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:17196–205. 10.3748/wjg.v20.i45.17196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ho T-W, Wu J-M, Kuo T-C, et al. Change of both endocrine and exocrine Insufficiencies after acute pancreatitis in non-diabetic patients: a nationwide population-based study. Medicine 2015;94:e1123. 10.1097/MD.0000000000001123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shen H-N, Yang C-C, Chang Y-H, et al. Risk of diabetes mellitus after First-Attack acute pancreatitis: a national population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 2015;110:1698–706. 10.1038/ajg.2015.356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tu J, Zhang J, Ke L, et al. Endocrine and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency after acute pancreatitis: long-term follow-up study. BMC Gastroenterol 2017;17:114. 10.1186/s12876-017-0663-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lee Y-K, Huang M-Y, Hsu C-Y, et al. Bidirectional relationship between diabetes and acute pancreatitis: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine 2016;95:e2448. 10.1097/MD.0000000000002448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]