Abstract

Objective

The intestinal epithelium is a rapidly renewing tissue which plays central roles in nutrient uptake, barrier function and the prevention of intestinal inflammation. Control of epithelial differentiation is essential to these processes and is dependent on cell type-specific activity of transcription factors which bind to accessible chromatin. Here, we studied the role of SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1, also known as ESET (SETDB1), a histone H3K9 methyltransferase, in intestinal epithelial homeostasis and IBD.

Design

We investigated mice with constitutive and inducible intestinal epithelial deletion of Setdb1, studied the expression of SETDB1 in patients with IBD and mouse models of IBD, and investigated the abundance of SETDB1 variants in healthy individuals and patients with IBD.

Results

Deletion of intestinal epithelial Setdb1 in mice was associated with defects in intestinal epithelial differentiation, barrier disruption, inflammation and mortality. Mechanistic studies showed that loss of SETDB1 leads to de-silencing of endogenous retroviruses, DNA damage and intestinal epithelial cell death. Predicted loss-of-function variants in human SETDB1 were considerably less frequently observed than expected, consistent with a critical role of SETDB1 in human biology. While the vast majority of patients with IBD showed unimpaired mucosal SETDB1 expression, comparison of IBD and non-IBD exomes revealed over-representation of individual rare missense variants in SETDB1 in IBD, some of which are predicted to be associated with loss of function and may contribute to the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation.

Conclusion

SETDB1 plays an essential role in intestinal epithelial homeostasis. Future work is required to investigate whether rare variants in SETDB1 contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD.

Keywords: IBD, epithelial differentiation, gut inflammation, IBD - genetics, intestinal epithelium

Summary box.

What is already known on this subject?

Cell fate decisions in intestinal crypts rely on cell type-specific transcription factor activity in the presence of a permissive chromatin structure.

Little is known about the role of repressive histone marks in the intestinal epithelium.

SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1, also known as ESET (SETDB1) is a H3K9 methyltransferase important for heterochromatin formation, genome stability and lineage commitment.

What are the new findings?

SETDB1 plays a fundamental role in intestinal epithelial differentiation and survival.

Missense and predicted loss-of-function variants are under-represented in human SETDB1, consistent with a critical role of SETDB1 in human biology.

Mucosal SETDB1 expression is maintained in the vast majority of patients with IBD, but rare missense variants over-represented in IBD can be identified and may contribute to IBD pathogenesis.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

Rare variants in SETDB1 may contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD, which needs to be addressed in future work.

The identification of environmental regulators of SETDB1 expression may reveal targets for therapeutic modulation of SETDB1 expression.

Introduction

The intestinal epithelium consists of a single dynamic layer of phenotypically and functionally distinct cells, which play essential roles in the absorption of nutrients and water, hormonal regulation and control of the microbiota.1 2 These functions are maintained in the presence of a rapidly renewing tissue, in which most epithelial cell types are exchanged within days.1 2 The importance of a well-controlled dynamic equilibrium of intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) is illustrated by the observation that conditions associated with disruption of epithelial proliferation, abrogation of IEC differentiation and loss of cellular adhesion are associated with severe defects in intestinal homeostasis and often mortality.3–8

The cellular identity of IEC subtypes is promoted and maintained by cell type-specific transcriptional programmes.9 10 While epigenetic processes such as histone modifications shape the chromatin landscape and can influence the accessibility of DNA to tissue-specific transcription factors, studies in the intestinal epithelium have revealed a largely permissive chromatin structure at least among early secretory and absorptive progenitors.11 Early intestinal epithelial lineage decisions are thus not governed by distinct distribution of histone marks that signify accessible chromatin, such as H3K4me2 and H3K27ac, but instead largely rely on cell type-specific transcription factor activity in the presence of a permissive chromatin structure, which is in line with remarkable plasticity of the intestinal epithelium.1 2 11

While the distribution of histone modifications associated with active chromatin is well-studied in the intestinal epithelium, less is known about the role of repressive histone marks such as methylations of H3K9 and H3K27. SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1, also known as ESET (SETDB1) is a methyltransferase with high specificity for the lysine 9 residue of histone H3.12–14 SETDB1 contributes to the generation of trimethyl H3K9 (H3K9me3), which marks heterochromatin and supports transcriptional repression.14–17 While constitutive deletion of Setdb1 in mice is associated with embryonic lethality,18 recent work in mice with inducible cell-specific deletion of Setdb1 has demonstrated a critical role of SETDB1 in hepatocyte differentiation17 and lineage commitment of T helper 1 (Th1) cells.19 Intriguingly, lineage integrity of Th1 cells is not governed by direct control of Th1 promoter activity but rather by tissue-specific H3K9me3-dependent repression of endogenous retroviruses (ERVs), which control Th1-specific enhancers.19 This is in line with observations by others that SETDB1 plays a central role in the repression of ERVs in various cell types, which influences cell fate decisions and is important for maintenance of genome stability. As such, deletion of SETDB1 and resulting de-repression of retrotransposable elements is associated with increased abundance of double-stranded RNA (dsRNA), induction of a type I interferon response and cell death of somatic cells.20 21 Conversely, high SETDB1 expression and silencing of transposable elements protects cancer cells from lethal drug exposure and contributes to the survival of drug-tolerant persister clones.22

While SETDB1 shows high expression in the intestine and particularly the intestinal epithelium, little is known about its role in epithelial homeostasis. Here, we show that SETDB1 has critical functions in the support of intestinal epithelial differentiation and survival. Loss of SETDB1 is associated with reactivation of ERVs, DNA damage and inflammation, which leads to rapid epithelial cell death and mortality in mice.

Methods

Mice

Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free (SPF) barrier facilities and were on C57BL/6J background. Mice carrying loxP-flanked alleles of Setdb1 (Setdb1 fl/fl)23 were crossed with Villin-Cre24 and Villin-CreERT2 25 mice to generate Villin-Cre Setdb1 fl/fl (Setdb1 ΔIEC) and Villin-CreERT2 Setdb1 fl/fl (Setdb1 indΔIEC), respectively. Embryos were obtained by timed mating of Setdb1 fl/fl and Villin-Cre Setdb1 fl/wt males and females. The morning after timed mating was considered as embryonal day (E) 0.5. Pregnant females were sacrificed on day 14 or 16 postcoitum, embryos (E14.5 and E16.5, respectively) were extracted and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. TNFΔARE mice have been described before.26 For dextran sulfate sodium (DSS) colitis, mice received 2.5% DSS in drinking water for five consecutive days, followed by 3 days of normal drinking water. Analysis of mice was performed at day 8 after starting DSS treatment. Animal studies were conducted in a mixed gender and age-matched manner using littermates for each experiment.

Tamoxifen treatment

To induce Setdb1 deletion, Setdb1 indΔIEC mice received five consecutive intraperitoneal injections of 1 mg tamoxifen (TAM) in sunflower oil, followed by a sixth injection on day 7. TAM-treated Setdb1 fl/fl littermates were used as controls. Mice were euthanized at the indicated time points after the first TAM injection.

Oral glucose tolerance test, analysis of barrier dysfunction and analysis of serum and stool

Mice were treated with TAM as described. On day 10, mice were fasted for 6 hours, weighed and blood glucose at time point zero was measured using the Accu-Chek Aviva blood glucose metre. Mice were orally administered with 2 mg/g body weight of glucose in water and blood glucose was measured at 15, 30, 60 and 120 min marks post-gavage.

For analysis of barrier dysfunction, mice were orally administered 0.6 mg/g body weight of fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran (4 kDa, Sigma-Aldrich) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and blood was collected after 4 hours. Relative fluorescence units were measured in serum using a FlexStation 3 microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

For serum and stool analysis, serum from Setdb1 indΔIEC mice and wild-type littermates, as well as small intestinal fluid (stool) from Setdb1 indΔIEC mice were collected on day 10 after the first TAM injection. Glucose and electrolyte (K+) concentrations, as well as osmolality were determined in both serum and stool; specifically, glucose and electrolyte analysis was performed with a Cobas8000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics), while osmolality was determined with an osmometer (Osmometer auto, Gonotec GmbH).

Histopathological analysis

Histopathological analysis was performed on H&E-stained sections of intestinal samples of Setdb1 ΔIEC mice aged 5 weeks and 1 year, as well as TAM-treated Setdb1 indΔIEC mice at day 10. Length and width of villi as well as neutrophil crypt infiltration were determined on H&E-stained ileal sections. Inflammation scoring was performed according to Wirtz et al 27 with the following scores: 0—no evidence of inflammation, 1—scattered infiltrating mononuclear cells, 2—moderate inflammation with multiple foci of infiltrating mononuclear cells, 3—additional increase in vascular density and marked bowel wall thickening, 4—additional transmural leucocyte infiltration.

For the evaluation of cellular necrosis, periodic acid-Schiff-stained ileum sections were assessed in a semi-quantitative manner and scored on a scale of 0 (no swelling) to 5 (maximal swelling). Five high power fields (HPFs) were evaluated in a strictly double-blinded manner in at least nine samples of each group. In parallel, the same sections were scored for the overall amount of necrotic debris/lost membrane integrity in the typical location of the crypt bottom, referred to as ‘crypt necrosis’ on a semi-quantitative scale of 0 (no crypt necrosis) to 5 (complete necrosis). Finally, the numbers of necrotic cells were counted in five HPF for at least nine samples of each evaluated group. Necrosis was further examined on subcellular level by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), examining for mitochondrial swelling and fragmentation, loss of microvilli as well as nuclear and cellular swelling.28

Immunohistochemistry, immunofluorescence, enzyme histochemistry

Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescence staining was performed using paraffin-embedded tissues as mentioned before,29 with the exception of SGLT1 staining where Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, pH 9.0) was used for antigen retrieval. For immunohistochemistry, antibodies against SETDB1 (D4M8R, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology), phospho-histone H2A.X (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology), OLFM4 (D6Y5A, 1:400, Cell Signaling Technology), SGLT1 (1:100, Abcam), Ly6G (E6Z1T, 1:200, Cell Signaling Technology) and F4/80 (D2S9R, 1:300, Cell Signaling Technology) were used for staining overnight at 4°C. For detection, Envision antirabbit IgG (Dako) was used according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

For 5’-bromo-2’-deoxyuridine (BrdU) labelling, mice were injected with 1 mg of BrdU (BD Bioscience) intraperitoneally 2 hours prior to sacrifice. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the BrdU In-situ Detection Kit (BD Pharmingen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

For immunofluorescence, antibodies against Ki67 (D3B5, 1:400, Cell Signaling Technology), cleaved caspase 3 (5A1E, 1:400, Cell Signaling Technology), mucin 2 (H-300, 1:100, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), lysozyme C (C-19, 1:400, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and chromogranin A (1:400, Abcam) were used for staining overnight at 4°C.

For cell death analysis, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) was performed using the In-Situ Cell Death Detection Fluorescein Kit (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Enzyme histochemistry using paraffin-embedded tissues was performed to detect alkaline phosphatase. Sections were incubated with 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (Roche) and nitro blue tetrazolium (Roche) substrate in AP buffer (0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 9.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 M MgCl2; 37°C) for 15 min, rinsed twice with PBS, once in dH2O, counterstained with Nuclear Fast Red solution (Sigma) for 25 s and embedded in Entellan.

Isolation of intestinal epithelium and crypts

Small intestinal epithelium and crypts were isolated as previously described.29 30 Cell pellets were either resuspended in RLT Buffer (Qiagen, supplemented with β-mercaptoethanol 10 µl/mL) to be used for RNA isolation, real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) or RNA sequencing; or in 1X RIPA buffer supplemented with cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) and Halt Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific) and further processed for protein isolation.

RNA isolation and real-time qPCR

Tissue RNA was isolated using the peqGOLD Total RNA Kit (Peqlab, VWR); 2 µg RNA were transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse-Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and qPCR was performed as described previously.31 Primers are listed in online supplementary table 1. RNA from isolated epithelial cells was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen).

gutjnl-2020-321339supp001.xlsx (12.1KB, xlsx)

RNA sequencing and data analysis

mRNA was isolated from 500 ng total RNA by poly-dT enrichment using the NEBNext Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Isolation Module (NEB) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were then directly subjected to the workflow for strand-specific RNA-Seq library preparation (Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep, NEB). For ligation, custom adaptors were used (Adaptor-Oligo 1: 5'-ACA CTC TTT CCC TAC ACG ACG CTC TTC CGA TCT-3', Adaptor-Oligo 2: 5'-P-GAT CGG AAG AGC ACA CGT CTG AAC TCC AGT CAC-3'). After ligation, adapters were depleted by an XP bead purification (Beckman Coulter) adding the beads solution in a ratio of 1:0.9. Dual indexing was done during the following PCR enrichment (12 cycles, 65°C) using custom amplification primers (primer 1: AAT GAT ACG GCG ACC ACC GAG ATC TAC AC NNNNNNNN ACA TCT TTC CCT ACA CGA CGC TCT TCC GAT CT; primer 2: CAA GCA GAA GAC GGC ATA CGA GAT NNNNNNNN GTG ACT GGA GTT CAG ACG TGT GCT CTT CCG ATC T). After two more XP bead purifications (1:0.9), libraries were quantified using the Fragment Analyzer (Agilent). For sequencing, samples were equimolarly pooled and sequenced 75 bp single end on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina), resulting in on average 30 million reads per sample. After sequencing, RNA-SeQC (1.1.8)32 was used to perform a basic quality control which includes exonic, intronic and intergenic distribution of the reads and rRNA rate within each samples. Alignment of the reads to the mouse reference (mm10) was done with GSNAP (v2018-07-04),33 and Ensembl gene annotation V.92 was used to detect splice sites. The uniquely aligned reads were counted with featureCounts (V.1.6.3)34 and the same Ensembl annotation. Normalisation of the raw read counts based on the library size and testing for differential expression between the two conditions was performed with the DESeq2 R package (V.1.24)35 and IHW (V.1.12.0).36 RNA sequencing data is available at NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) under accession number GSE150836.

For ERV analysis, aligned reads were analysed using RepEnrich237 with Repeat Library 20 140 131 Annotation.38 EdgeR (V.3.26.839) was used to detect differentially expressed repetitive elements.

Human mucosal transcriptomes and genetic variants

Quantile normalised counts were obtained from a recently described transcriptome analysis.40 All study participants had given written informed consent prior to sampling and data collection. In addition, we re-analysed mucosal transcriptome data obtained by Planell et al 41 and Olsen et al,42 for which data were obtained through the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, accession numbers GDS4365 and GDS3119). For further information on patient characteristics and ethics approval, please refer to the respective publications.

Data on genetic variants was obtained from the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD,43 https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org) and the IBD Exomes Browser (http://ibd.broadinstitute.org).

Protein isolation and western blot analysis

For protein isolation, crypts were incubated in 1X RIPA buffer supplemented with cOmplete Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche) and Halt Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktail (Thermo Scientific) for 1 hour at 4°C, centrifuged (14 000 rpm, 4°C, 10 min) and supernatant was collected. For western blot analysis, 60 µg protein was separated by 7.5% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Blots were blocked with 5% milk in Tris Buffered Saline-Tween 20 and the following primary antibodies were applied: anti-p53 (D2H90, 1:1000, Cell Signaling Technology) and GAPHD (ABS16, 1:1000, Merck Milipore). Proteins of interest were detected using Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad) and imaged on ImageQuant LAS 4000.

Transmission electron microscopy

For TEM, intestine was dissected and fixed in 4% formaldehyde (prepared from paraformaldehyde) in 100 mM PBS. After several washes in PBS and water, the samples were dissected further into 1 mm tissue blocks and postfixed in modified Karnovsky’s fixative (2% glutaraldehyde, 2% paraformaldehyde in 50 mM HEPES) for at least overnight at 4°C.44 45 Samples were washed in 100 mM HEPES and water, postfixed/stained in 2% aqueous OsO4 solution containing 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide and 2 mM CaCl2. After washing, samples were incubated in 1% thiocarbohydrazide, washed again and contrasted in 2% osmium in water for a second time.46 After several washes in water, samples were en bloc contrasted with 1% uranyl acetate/water, washed again in water, dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol, infiltrated in the epon substitute EMbed 812 (1+2, 1+1, 2+1 epon/ethanol mixtures, 2×pure epon) and finally embedded in flat embedding moulds. Ultrathin sections were cut with a Leica UC6 ultramicrotome and collected on formvar-coated slot grids. Sections were contrasted with uranyl acetate and with lead citrate and imaged with a Jeol JEM1400 Plus (Ruby, JEOL) running at 80 kV acceleration voltage.

Statistics

For datasets of unknown or skewed distribution, non-parametric statistical analysis was performed. Measures of centre and variability as well as the statistical tests applied are described for each dataset in the figure legend. Prism V.8 from GraphPad Software was used to calculate P values.

Results

Mice with constitutive intestinal epithelial deletion of SETDB1 are not born at Mendelian ratios and show mosaic SETDB1 expression

To delete Setdb1 selectively in IECs, we crossed Setdb1 fl/fl mice with Villin-Cre mice, which express Cre recombinase under control of the IEC-specific Villin promoter.24 Crossings of Villin-Cre Setdb1 fl/wt mice with Setdb1 fl/fl showed significant under-representation of mice with homozygous IEC-specific Setdb1 deletion (Villin-Cre Setdb1 fl/fl, hereafter Setdb1 ΔIEC mice) (online supplementary figure 1A), suggesting embryonic lethality. In line with this concept, Setdb1 ΔIEC embryos were observed at expected ratios at 14.5 days postconception (dpc), but under-represented at 16.5 dpc (online supplementary figure 1B, C). Those Setdb1 ΔIEC mice born developed largely normal with only a non-significant trend towards reduced weight gain and growth (online supplementary figure 1D, E). Histological evaluation of the small intestine of adult Setdb1 ΔIEC mice showed occasional areas of bifurcated or trifurcated villi, crypt fission and a cuboid shape of IECs (online supplementary figure 1F). Since Setdb1 ΔIEC mice were not born at Mendelian ratios and only showed patchy alterations in intestinal epithelial architecture, we investigated intestinal epithelial Setdb1 expression in these mice. Setdb1 ΔIEC mice showed only a modest reduction in Setdb1 expression, which reached statistical significance in the colon but not in the small intestine (online supplementary figure 1G). Immunohistochemical staining confirmed that SETDB1 expression in the intestine is largely confined to the intestinal epithelium and revealed that areas with epithelial alterations in Setdb1 ΔIEC mice were characterised by mosaic expression of SETDB1 with crypts lacking SETDB1 expression adjacent to crypts with normal SETDB1 expression that had escaped deletion (online supplementary figure 1H). Similar observations were made in mouse embryos which survived until 16.5 dpc (online supplementary figure 1I). Selective analysis of crypts with loss of SETDB1 protein expression in adult Setdb1 ΔIEC mice showed a modest increase in epithelial proliferation compared with Villin-Cre-negative Setdb1 fl/fl littermates and to Setdb1 ΔIEC crypts that had escaped deletion (online supplementary figure 2A). In addition, villus bifurcations were selectively observed in regions with loss of SETDB1 expression and crypt fission was also predominantly found in areas with loss of SETDB1 expression (online supplementary figure 2B). However, the vast majority of the small intestinal epithelium showed normal expression of SETDB1 without epithelial alterations (data not shown). Accordingly, Setdb1 ΔIEC mice demonstrated largely unaltered RNA expression of markers of intestinal epithelial differentiation (online supplementary figure 2C). However, aged Setdb1 ΔIEC mice showed an increase in crypt infiltration by neutrophils (online supplementary figure 2D), modest villus blunting (online supplementary figure 2E), and occasional areas of transmural immune cell infiltration (online supplementary figure 2F), consistent with mild intestinal inflammation of incomplete penetrance. These results demonstrate that constitutive intestinal epithelial deletion of Setdb1 is associated with embryonic lethality, while surviving mice largely escape deletion of Setdb1. This suggests a critical role of SETDB1 in the intestinal epithelium.

gutjnl-2020-321339supp005.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp006.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

Loss of epithelial Setdb1 is associated with intestinal inflammation and early mortality

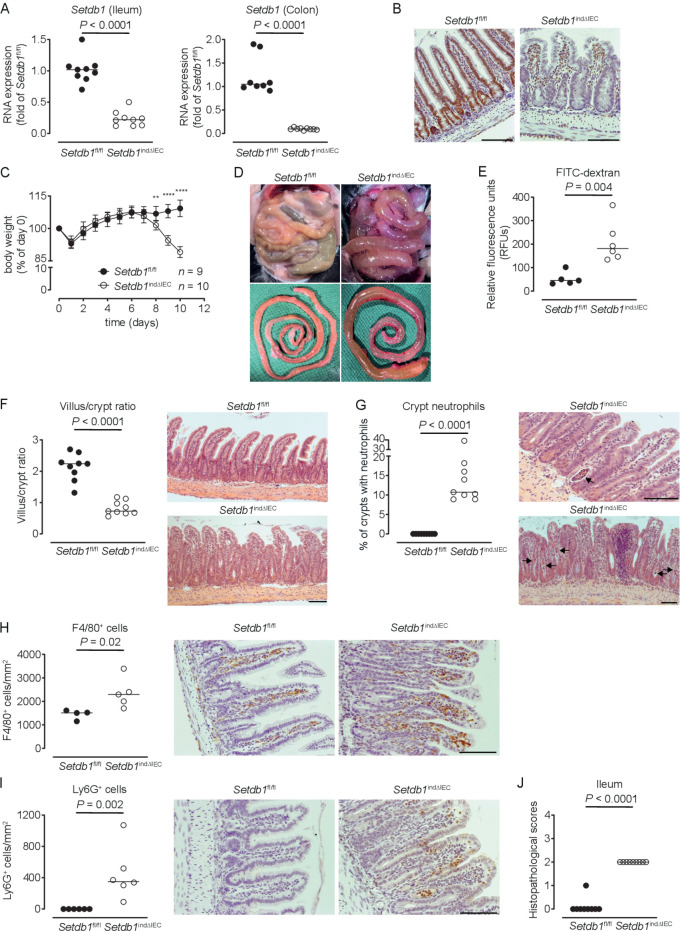

To limit escape from Setdb1 deletion, we generated Villin-CreERT2 Setdb1 fl/fl mice (hereafter, Setdb1 indΔIEC mice), which allow for TAM-inducible IEC-specific deletion of Setdb1.25 Setdb1 indΔIEC mice were born at Mendelian ratios and developed normally, as expected. In contrast to Setdb1 ΔIEC mice, TAM injection of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice was associated with robust IEC-specific deletion of Setdb1 as confirmed by quantitative PCR (figure 1A) and immunohistochemical staining (figure 1B). Starting at day 7 after the first TAM administration, Setdb1 indΔIEC mice showed diarrhoea and progressive loss of weight, which was not observed in TAM-injected Villin-CreERT2-negative Setdb1 fl/fl littermates (figure 1C). At day 10 after the first TAM injection, all Setdb1 indΔIEC mice had to be sacrificed due to lethargy, severe weight loss and dehydration. Necropsy showed dilated, fluid-filled small intestines in these mice (figure 1D). Gavage with FITC-dextran confirmed intestinal barrier dysfunction in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice (figure 1E), consistent with intestinal fluid loss. Histological evaluation of the small intestine revealed massive villus blunting and modest crypt elongation leading to a substantial increase in the villus/crypt ratio (figure 1F, online supplementary figure 3A, B). In addition, Setdb1 indΔIEC mice showed increased immune cell density in the lamina propria (figure 1F), crypt infiltration by neutrophils (figure 1G) and increased numbers of macrophages and neutrophils in the lamina propria (figure 1H–I), consistent with intestinal inflammation (figure 1J). The ileal mucosa of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice further showed increased expression of chemokines, cytokines and other acute phase proteins and inflammatory mediators (online supplementary figure 3C). Similar findings were made in colon with inflammation (online supplementary figure 3D), focal loss of the surface epithelium (online supplementary figure 3E), large amounts of cellular debris as well as mucus in the intestinal lumen (online supplementary figure 3E) and a reduction in colon length (online supplementary figure 3F).

Figure 1.

Induced intestinal epithelial Setdb1 deletion is associated with inflammation and mortality. (A) RNA expression of Setdb1 in ileum and colon of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection as determined by quantitative PCR. (B) Representative immunohistochemistry staining of SETDB1 in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains on 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. Note loss of the epithelial signal and conserved staining of SETDB1 in the lamina propria of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice. (C) Body weight of the indicated mouse strains following tamoxifen injection start at day 0. Mean±SD is shown. **P≤0.01; ****P≤0.0001. (D) Representative images at necropsy of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (E) Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-dextran measurement in serum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (F) Villus-crypt ratio as well as representative H&E staining of ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (G) Percentage of crypts containing neutrophil granulocytes (left) and representative H&E stainings (right) of ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. The arrows highlight crypt abscesses. (H–I) F4/80 (H) and Ly6G (I) immunohistochemistry with quantification (left) and representative images (right) in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (J) Inflammation scores in the small intestine of the indicated mice as obtained by analysis of H&E stainings. Representative results of two-three independent experiments are shown (A–J). In (A, E–J), dots represent individual mice and the bar indicates the median. Size bars indicate 100 µm. The Mann-Whitney U test (A, E–J) or Student’s t-test (C) were applied. SETDB1, SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1, also known as ESET.

gutjnl-2020-321339supp007.pdf (348.4KB, pdf)

SETDB1 is required for intestinal epithelial differentiation and stem cell survival

The intestinal epithelium of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice showed a cuboid shape of IECs with large euchromatin-enriched nuclei, consistent with loss of heterochromatin (figure 2A). Electron microscopy confirmed the presence of a disorganised epithelium (figure 2B) with irregularly shaped enterocytes and enterocyte nuclei (figure 2B–C, online supplementary figure 4A) and an altered microvillus structure (figure 2B–C, online supplementary figure 4B). In accordance with defects in intestinal epithelial differentiation, mucin-2 (Muc2)-positive goblet cells and serotonin and chromogranin A-positive enteroendocrine cells were substantially reduced in the small intestine of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice (figure 2D–G). Lysozyme-positive Paneth cells were largely preserved in the small intestinal crypt bottom of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice (figure 2H, online supplementary figure 4C). Setdb1 indΔIEC mice also showed mispositioned Paneth cells along the villus axis and aberrant secretory cells positive for both Muc2 and lysozyme at villus tips (figure 2I). Of note, the life span of Paneth cells47 significantly exceeds that of survival of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice, which may contribute to limited Paneth cell alterations in these mice.

Figure 2.

Altered intestinal epithelial differentiation in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice. (A) Representative H&E stainings of ileal villus tips of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. Arrows indicate bright, round nuclei in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice. (B–C) Representative electron microscopy (EM) images of ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. Arrows indicate disorganised epithelium (B). In (C), a cuboid Setdb1 indΔIEC enterocyte is shown and the arrowhead highlights an irregularly shaped nucleus (N). The red line shows the basal membrane. (D, F) RNA expression of the indicated genes as determined by quantitative PCR in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (E) Representative immunofluorescence staining of mucin-2 (Muc2) (red) in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. Arrows indicate goblet cells in wild-type (WT) mice. (G–H) Representative immunofluorescence stainings of Chga (G), green, Lyz1 (H), green and double stainings for Lyz1 (green) and Muc2 (red) (I) in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. Quantification of Lyz1-positive cells is shown on the left in (H). Arrowheads in (I) indicate Lyz1 and Muc2 double-positive cells. Representative results of three independent experiments are shown (A, D–I). EM images (B–C) are representative of three mice per group. In (D, F, H), dots represent individual mice and the bar indicates the median. Size bars indicate 50 µm (A, E, G–I), 10 µm (B, C). The Mann-Whitney U test (D, F, H) was applied. SETDB1, SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1, also known as ESET.

gutjnl-2020-321339supp008.pdf (9.2MB, pdf)

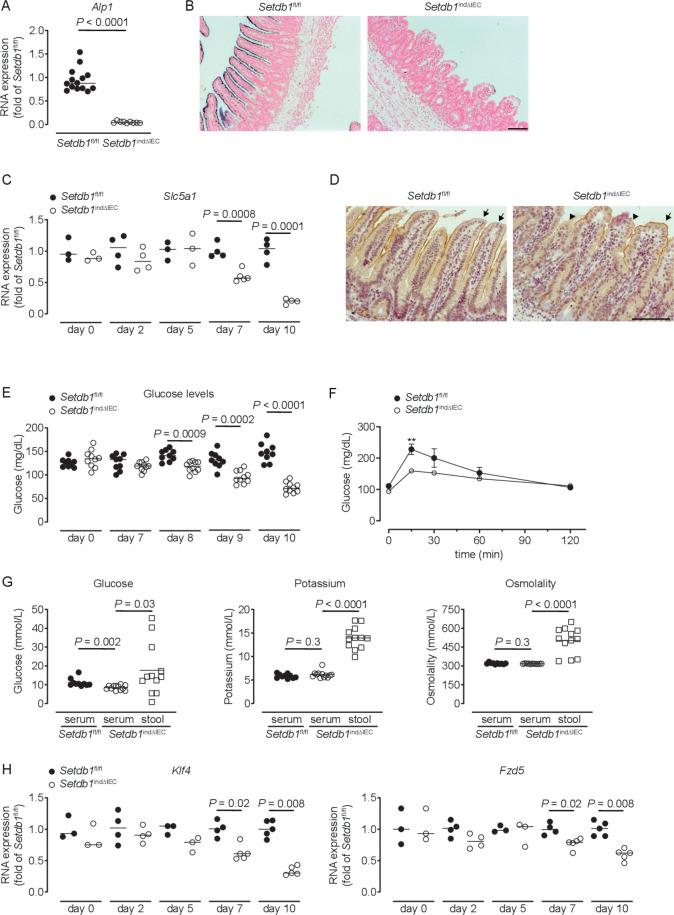

Setdb1 indΔIEC mice showed a dramatic reduction in the expression and activity of alkaline phosphatase, a marker of differentiated enterocytes (figure 3A–B). Differentiated small intestinal IECs play critical roles in the absorption of glucose from the intestinal lumen, which involves the apical glucose transporter SGLT1 (Slc5a1) and the basolateral glucose transporter GLUT2 (Slc2a2).48 In Setdb1 indΔIEC mice, SGLT1 expression showed a progressive reduction in expression (figure 3C), with a near-complete loss of SGLT1 expression in the apical cell membrane of IECs shortly before death (figure 3D), while GLUT2 expression remained unaltered (online supplementary figure 5A). Blood glucose levels showed a similar decrease over time with pronounced hypoglycaemia at day 10 after the first TAM injection (figure 3E). Oral glucose gavage confirmed defects in intestinal glucose absorption in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice (figure 3F). In line with these defects, the glucose concentration was higher in the intestinal lumen compared with serum of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice, with similar effects on potassium (figure 3G). Accordingly, the osmolality was higher in the intestinal lumen compared with serum of these mice (figure 3G), which is anticipated to result in osmotic diarrhoea and explains the fluid-filled small intestines of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice.

Figure 3.

Loss of enterocyte differentiation in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice is associated with hypoglycaemic. (A, C, H) RNA expression of the indicated genes as determined by quantitative PCR in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains (A), 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (B) Representative alkaline phosphatase enzyme histochemistry in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (D) Representative immunohistochemistry staining for SGLT1 in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. Arrows show intact SGLT1 staining and arrowheads loss of SGLT1 staining. (E–F) Blood glucose levels (E) and glucose tolerance test (F) of the indicated mouse strains at the indicated time points (E) or 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection (F). **P<0.01. (G) Glucose and potassium concentrations as well as osmolality in the serum and small intestinal luminal content (stool) of the indicated mice 10 days after tamoxifen administration. Representative results of two-three independent experiments are shown. In (A, C, E, H), dots represent individual mice and the bar indicates the median. In (F), mean±SEM is shown. In (G), the bar indicates the mean. Size bars indicate 100 µm. The Mann-Whitney U test (A, C, E, H), the Student’s t-test (F) or one-way analysis of variance (G) were applied. SETDB1, SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1, also known as ESET.

gutjnl-2020-321339supp009.pdf (91.3KB, pdf)

To provide insight into the mechanisms of intestinal epithelial alterations in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice, we analysed the expression of genes centrally involved in epithelial differentiation. While the majority of the investigated genes showed minor or no changes in expression in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice (online supplementary figure 5B), the transcription factor Krüppel-like factor 4 (Klf4) and the Wnt receptor Frizzled-5 (Fzd5) exhibited progressive loss of expression in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice (figure 3H). Deletion of Klf4 in the intestinal epithelium is associated with defects in terminal maturation of absorptive enterocytes, loss of alkaline phosphatase expression and mispositioning of Paneth cells along villi.49 Deletion of Fzd5 is also associated with mispositioning of Paneth cells.50 As such, altered Klf4 and Fzd5 expression in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice likely contribute to impaired terminal differentiation of absorptive enterocytes and mispositioning of Paneth cells. The transcription factor Foxa1, which promotes goblet and enteroendocrine differentiation51 was increased in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice, potentially as a compensatory mechanism in the presence of goblet and enteroendocrine cell loss. Together, these findings suggest that deletion of Setdb1 and resulting defects in heterochromatin formation are associated with loss of the cellular identity of most IEC types. This is anticipated to result both from direct alterations in the expression of genes associated with terminally differentiated IECs as well as from indirect effects on the expression of transcription factors (Klf4) and signalling mediators (Fzd5) involved in the regulation of epithelial differentiation.

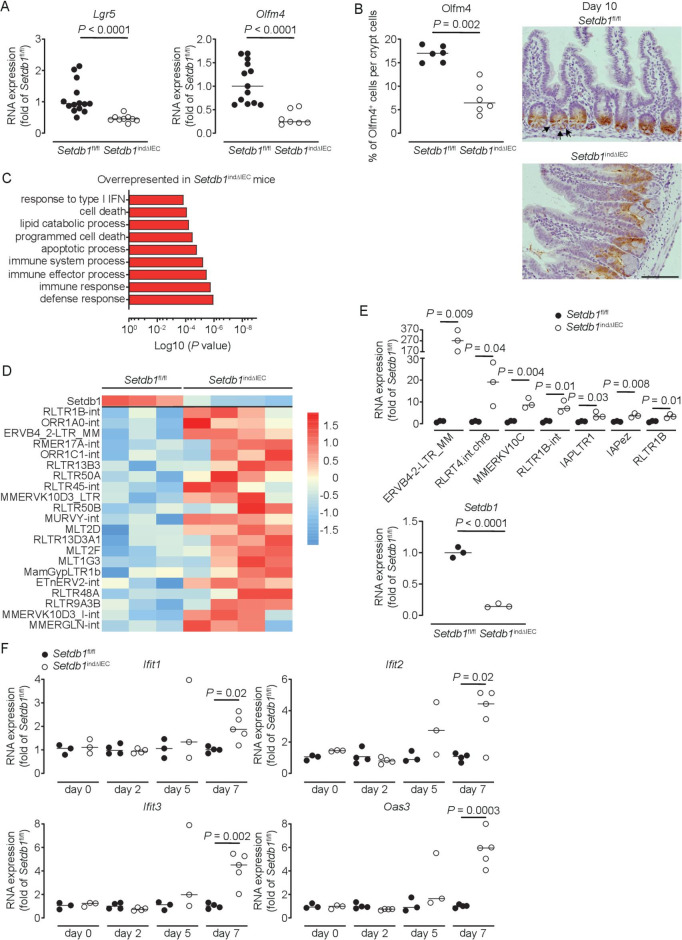

Shortly before death, small intestinal crypt bottoms of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice seemed entirely composed of Paneth cells, although Paneth cell numbers were not increased in these mice (figure 2H). This raised the question of whether intestinal stem cells (ISCs), which are located between Paneth cells at the crypt bottom, are lost in response to intestinal epithelial deletion of Setdb1. Indeed, small intestinal IECs obtained from Setdb1 indΔIEC mice showed a substantial reduction in the expression of the stem cell genes Lgr5 and Olfm4 on day 9 after Setdb1 deletion (figure 4A). While residual OLFM4+ ISCs were still present in the small intestinal crypt bottom of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice at this time (online supplementary figure 6A), crypt bottoms were completely devoid of ISCs on day 10 (figure 4B). However, proliferation, at least among transit-amplifying cells was preserved until day 10 after Setdb1 deletion (online supplementary figure 6B). Together, these data reveal a critical role of Setdb1 in intestinal epithelial differentiation and stem cell survival.

Figure 4.

Setdb1 deletion leads to de-repression of endogenous retroviruses and induction of a type I interferon response. (A) RNA expression of Lgr5 and Olfm4 as determined by quantitative PCR (qPCR) in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains 9 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (B) Quantification and representative immunohistochemistry staining of OLFM4 in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains 10 days after the first tamoxifen injection. Arrows show intestinal stem cells (ISCs) in Villin-CreERT2-negative Setdb1 fl/fl mice. (C) Gene ontology (GO) terms of the top 100 upregulated genes in RNA sequencing of small intestinal crypts of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice 2 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (D) Heatmap of the expression of Setdb1 (top) and endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) (below) as obtained from RNA sequencing of small intestinal crypts of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice 2 days after the first tamoxifen injection. (E) Expression of the indicated ERVs (top) and Setdb1 (below) in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains 5 days after the first tamoxifen injection as determined by qPCR. (F) RNA expression of the indicated genes as determined by qPCR in the small intestine of mice at the indicated time points after the first tamoxifen injection. Representative results of two-three independent experiments are shown (A–B, E–F). RNA sequencing was performed once (C–D). In (A–B, E–F), dots represent individual mice and the bar indicates the median. Size bars indicate 100 µm. The Mann-Whitney U test (A–B, E–F) was applied. SETDB1, SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1, also known as ESET.

gutjnl-2020-321339supp010.pdf (1.9MB, pdf)

SETDB1 contributes to the silencing of endogenous retroviruses and prevents DNA damage

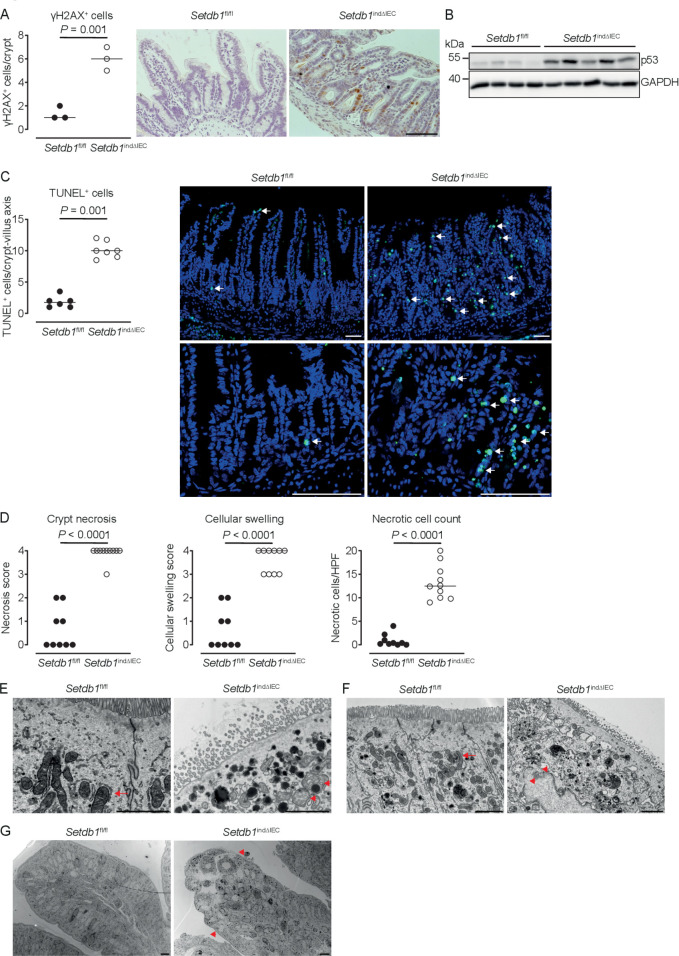

We next addressed the mechanisms through which SETDB1 regulates intestinal homeostasis. To distinguish primary effects of Setdb1 deletion in IECs from secondary consequences of altered epithelial differentiation and progressive inflammation, we performed an RNA sequencing of intestinal crypts 2 days after the first TAM injection. While Setdb1 expression was only reduced to 50% of the level observed in TAM-injected Villin-CreERT2-negative Setdb1 fl/fl littermates at this early time point (online supplementary figure 6), gene ontology (GO) term analysis revealed a signature of cell death, inflammation and type I interferon signalling (figure 4C, online supplementary table 2). Setdb1 is critical for heterochromatin formation and the silencing of ERVs.20 21 Accordingly, Setdb1 deletion has been demonstrated to be associated with de-silencing of retrotransposable elements, genomic instability and activation of type I interferon signalling by double-stranded RNA, ultimately leading to cell death or malignant transformation.20 21 In line with these findings, RNA sequencing of crypts 2 days after the first TAM injection already showed a consistent increase in the expression of several ERVs in Setdb1 indΔIEC mice (figure 4D), which correlated with the degree of downregulation of Setdb1 expression (figure 4D, top line). At later time points, when Setdb1 expression was further decreased (figure 4E, lower panel), ERVs exhibit a dramatic increase in expression (figure 4E). This was associated with progressive induction of a type I interferon signature in the small intestine of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice (figure 4F). In addition, IECs of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice showed a substantial induction of histone H2AX phosphorylation (γH2AX), a marker of DNA damage, which was most pronounced in the crypt epithelium (figure 5A) and was associated with the accumulation of p53 (figure 5B). Accordingly, the small intestinal epithelium of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice showed a dramatic increase in cell death as determined by TUNEL staining (figure 5C). While RNA sequencing at early time points suggested an induction of apoptosis (figure 4C), in line with p53 accumulation (figure 5B), analysis of cleaved caspase 3 at later stages failed to demonstrate any notable evidence of apoptosis in IECs of Setdb1 indΔIEC mice or Villin-CreERT2-negative littermates (online supplementary figure 6D). Instead, Setdb1 indΔIEC mice demonstrated evidence of epithelial necrosis with cellular swelling and necrotic cells in crypts (figure 5D). This was confirmed by electron microscopy which showed swelling and loss of the structural integrity of mitochondria (figure 5E–F), loss of integrity of other organelles and the nuclear membrane (figure 5F) and swelling of the cytoplasm as well as rupture of the plasma membrane (figure 5G). Together, these data demonstrate a critical role of SETDB1 in genome stabilisation within IECs. Loss of SETDB1 in the intestinal epithelium is associated with de-repression of ERVs, which leads to DNA damage, p53 accumulation and pronounced epithelial cell death and is associated with intestinal inflammation, defects in nutrient absorption and mortality.

Figure 5.

Loss of epithelial SETDB1 is associated with DNA damage and cell death. (A) Percentage of histone H2AX phosphorylation (γH2AX)-positive cells per crypt as determined by immunohistochemical staining (left) and representative stainings (right) in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains. (B) Western blot analysis for p53 and GAPDH in small intestinal intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) of the indicated mouse strains. (C) Percentage of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL)-positive cells per crypt (left) and representative immunofluorescence stainings (right, TUNEL in green) in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains. Arrows show TUNEL-positive IECs. (D) Quantification of crypt necrosis and cellular swelling as well as of the number of necrotic cells per high power field in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains. (E–G) Representative electron microscopy images in the ileum of the indicated mouse strains. Arrows indicate normal mitochondria (E–F). Arrowheads indicated swelling and loss of the structural integrity of mitochondria (E) and loss of integrity of the nuclear membrane (F) as well as swelling of the cytoplasm and rupture of the plasma membrane (G). All data were obtained at day 10 after the first tamoxifen injection. Representative results of two independent experiments are shown (A–G). In (A, C–D), dots represent individual mice and the bar indicates the median. Size bars indicate 100 µm in (A, C), 2 µm (E, F), 10 µm (G). The Student’s t-test (A) or the Mann-Whitney U test (C–D) were applied. SETDB1, SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1, also known as ESET.

gutjnl-2020-321339supp002.xlsx (20.4KB, xlsx)

Human SETDB1 expression and genetic variants in IBD

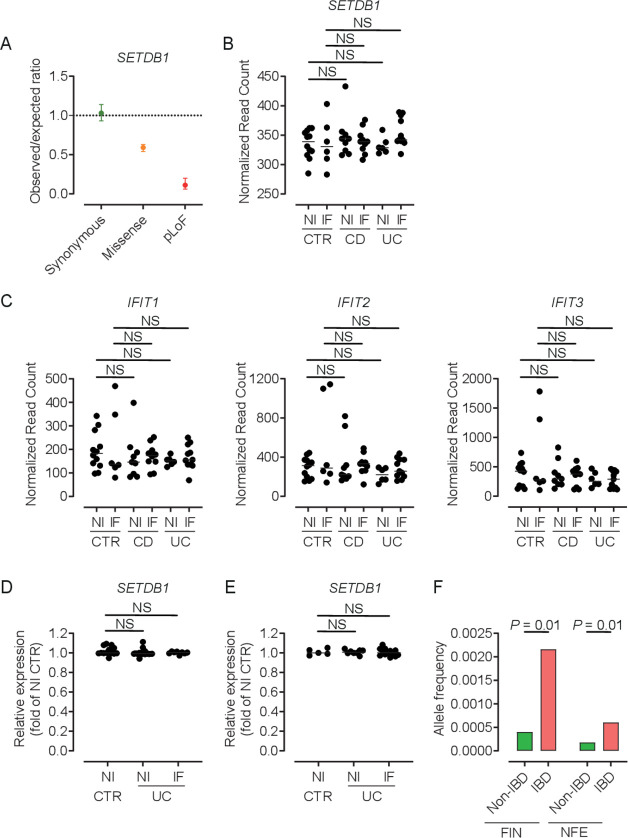

Our data demonstrate an essential role of SETDB1 in intestinal homeostasis in mice and show that loss of SETDB1 is not compatible with life. Of note, even a modest reduction in Setdb1 expression in mice is associated with de-repression of ERVs, type I interferon signalling and cell death (figure 4D–E), which is in line with the recent demonstration of haploinsufficiency of intestinal epithelial SETDB1 in mice.52 SETDB1 is highly conserved across mammals with 92% amino acid similarity between humans and mice,53 thus raising the question of whether SETDB1 plays a similarly fundamental role in human biology. In line with this concept, human SETDB1 exhibits low and very low observed-to-expected ratios of missense and predicted loss of function (pLoF) variants, respectively (figure 6A, Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD43)). Furthermore, SETDB1 shows a probability of being loss-of-function intolerant (pLI) score of 1 (gnomAD), which is consistent with haploinsufficiency and suggests that even modest dysregulation of SETDB1 expression may contribute to human pathology.

Figure 6.

Human SETDB1 expression and variants in IBD. (A) Observed-to-expected ratio of variants in SETDB1 based on the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD,43 https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org). pLoF, predicted loss-of-function variants. (B–C) Quantile normalised read count of the indicated genes as obtained by RNA sequencing of biopsies of inflamed (IF) or non-inflamed (NI) intestinal mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC), healthy controls (CTR NI) or disease controls (CTR IF). For a detailed description of the cohort, see Häsler et al.40 (D–E) Relative expression of SETDB1 in mucosal transcriptomes of the indicated patients. Patient cohorts were previously described by Planell et al 41 (D) and Olsen et al 42 (E). (F) Allele frequency of the 1:150935127 C/T variant (rs145309946, pArg1075Cys) in the Finnish (FIN) and non-Finnish European (NFE) IBD and non-IBD population as obtained through the IBD exomes browser (http://ibd.broadinstitute.org). The Kruskal-Wallis test (B–E) or the Fisher’s exact test (F) (for further information, see Rivas et al 54) was applied. NS, not significant; SETDB1, SET Domain Bifurcated Histone Lysine Methyltransferase 1, also known as ESET.

Intriguingly, Wang et al recently described that intestinal SETDB1 RNA and protein expression in patients with IBD is consistently reduced to about 50% of the level observed in controls, which suggests potential contributions to intestinal inflammation in the majority of patients with IBD.52 Given these data, we first examined Setdb1 expression in mouse models of intestinal inflammation and specifically in the DSS model of chemically induced colitis27 and in the TNFΔARE model of ileitis.26 In the ileum of TNFΔARE mice, compared with wild-type littermates, SETDB1 expression was unaffected and no evidence of a type I interferon signature detected (online supplementary figure 7A). In the DSS model, mice showed a substantial decrease in colonic Setdb1 expression (online supplementary figure 7B). However, DSS acts through toxic effects on IECs27 and SETDB1 expression is largely confined to the intestinal epithelium, suggesting that DSS-induced loss of IECs may contribute to reduced Setdb1 expression. In line with this concept, DSS-treated mice showed substantially reduced expression of the epithelial marker E-cadherin (Cdh1) (online supplementary figure 7B) and immunohistochemical staining confirmed that loss of the SETDB1 signal was restricted to epithelial erosions and ulcerations, while remaining epithelial cells demonstrated unimpaired SETDB1 expression (online supplementary figure 7C). Accordingly, a type I interferon signature was not detected in the colon of DSS-treated mice (online supplementary figure 7B).

gutjnl-2020-321339supp011.pdf (432.6KB, pdf)

Next, we examined the expression of SETDB1 in mucosal transcriptomes in a well-defined cohort of patients with inflamed or quiescent Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), disease controls and healthy controls.40 In contrast to observations by Wang et al,52 we found tight regulation of SETDB1 expression in all studied patient groups without evidence for decreased expression in IBD (figure 6B). In addition, we did not find evidence for a type I interferon signature in patients with IBD (figure 6C). This was confirmed in two independent cohorts described by Planell et al 41 and Olsen et al,42 who compared mucosal transcriptomes of active and inactive UC with non-IBD controls. Consistent with observations in our patient cohort, we did not find evidence of dysregulation of SETDB1 expression in these two independent IBD cohorts (figure 6D–E). Together, these results suggest that alterations in SETDB1 expression are not a common feature in IBD. However, rare missense and predicted loss-of-function variants have been described in SETDB1 (online supplementary table 3 and https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org), some of which are over-represented in IBD compared with non-IBD exomes (online supplementary table 4 and http://ibd.broadinstitute.org). This applies, for example, to p.Arg1075Cys (rs145309946), a rare missense variant in a conserved residue of SETDB1 (PhyloP 2.37, PhastCons 1), which is predicted to be damaging (MutationTaster) and over-represented in IBD compared with non-IBD exomes across different cohorts (figure 6F, online supplementary table 4). As such, it remains to be investigated whether rare variants in SETDB1 contribute to IBD pathogenesis.

gutjnl-2020-321339supp003.xlsx (71.8KB, xlsx)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp004.xlsx (47.6KB, xlsx)

Discussion

In this work, we have addressed the role of SETDB1, a H3K9 methyltransferase critical for heterochromatin formation, in the intestinal epithelium. We show that SETDB1 plays an indispensable role in intestinal epithelial homeostasis. Deletion of epithelial Setdb1 is associated with defects in intestinal epithelial differentiation, de-silencing of ERVs and mounting of an innate immune response characterised by a type I interferon signature, which likely occurs downstream of the sensing of dsRNA.20 21 52 DNA damage and p53 accumulation as well as progressive inflammation promote massive cell death within the intestinal epithelium, which is associated with breakdown of the intestinal barrier and loss of the intestinal stem cell compartment. In addition, altered epithelial differentiation with loss of transporters critical for nutrient absorption, such as SGLT1, further promotes mortality through metabolic dysfunction including severe hypoglycaemia and dehydration as a consequence of barrier breakdown and osmotic fluid shifts. Accordingly, attempts to constitutively delete Setdb1 in the intestinal epithelium were futile due to embryonic lethality. Those Setdb1 ΔIEC mice born showed partial escape from Setdb1 deletion with only focal areas of Setdb1 loss and neighbouring crypts that escaped deletion and maintained intestinal homeostasis. While we have not studied the mechanisms of escape from Setdb1 deletion in Setdb1 ΔIEC mice, similar observations of embryonic lethality and incomplete Setdb1 deletion have been made by others in the same mouse model.52 As such, these data highlight a critical role of SETDB1 and SETDB1-dependent heterochromatin formation in intestinal epithelial homeostasis, differentiation and survival.

Importantly, our findings are consistent with results recently obtained by others. As such, using similar mouse models, Wang et al demonstrated that intestinal epithelial deletion of Setdb1 is associated with de-repression of ERVs and an increase in double-stranded RNA, which is sensed by Z-DNA-binding protein 1 (ZBP1) and promotes necroptosis of enterocytes through interactions between ZBP1 and receptor-interacting protein kinase 3.52 Similar to our findings, inducible intestinal epithelial deletion of Setdb1 was associated with rapid development of intestinal inflammation, barrier breakdown and death.52 These results confirm a critical role of SETDB1 in intestinal homeostasis and demonstrate that loss of SETDB1 promotes necroptosis of IECs.

Intriguingly, even modest regulation of SETDB1 expression is associated with alterations in epithelial homeostasis. As such, even at early time points after TAM injection, when SETDB1 expression in IECs was only reduced to 50% of the level observed in wild-type littermates, RNA sequencing demonstrated a signature of de-repression of ERVs, type I interferon signalling and cell death (figure 4C–D). Setdb1 ΔIEC mice, which largely escaped Setdb1 deletion, also exhibited alterations in the intestinal architecture and mild intestinal inflammation (online supplementary figure 2D, E, F). Furthermore, Wang et al demonstrated intestinal inflammation on heterozygous intestinal epithelial Setdb1 deletion.52 These results suggest haploinsufficiency of intestinal epithelial SETDB1 in mice. In accordance with a similarly relevant role of SETDB1 in human biology, predicted loss-of-function variants in human SETDB1 are considerably less frequently observed than expected (figure 6A) with a pLI score of 1 (gnomAD), consistent with haploinsufficiency in humans. These data raise the possibility that even modest or transient regulation of SETDB1 expression, for example, in response to environmental factors, may negatively impact on epithelial function and promote intestinal inflammation. Intriguingly, and in line with this concept, Wang et al described a consistent reduction of SETDB1 expression in human patients with IBD, suggesting potential involvement of SETDB1 in the pathogenesis of IBD.52 However, these data were surprising in that features associated with loss of SETDB1, such as genome instability, are not commonly observed in IBD. We therefore analysed SETDB1 expression in unbiased mucosal transcriptome datasets of patients with IBD and controls obtained by us and others. These datasets revealed tight regulation of SETDB1 expression across and within patient populations, without evidence for decreased SETDB1 expression or a type I interferon signature in IBD. SETDB1 expression in the intestine is largely restricted to IECs and mouse models with loss of IECs such as the DSS model consequently show reduced intestinal SETDB1 expression (online supplementary figure 7C). Although speculative, it is therefore possible that sampling of areas of intestinal erosions and ulcerations may have contributed to the observation of decreased intestinal SETDB1 expression by Wang et al, which is distinct from our findings. In conclusion, in line with a fundamentally important role of SETDB1 in intestinal epithelial biology, alterations in SETDB1 expression are not a common feature in IBD and are thus unlikely to be a general mechanism promoting intestinal inflammation in IBD. However, rare variants in SETDB1 have been described, some of which are over-represented in patients with IBD (figure 6F). As such, it is possible that rare variants in SETDB1 contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD, potentially in a monogenic manner.

In conclusion, our work demonstrates a critical role of SETDB1 in intestinal epithelial homeostasis and the prevention of intestinal inflammation. Future work is required to investigate whether rare variants in SETDB1 can contribute to the pathogenesis of IBD.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank A. Caldarelli and B. Bazylak-Kaps for excellent technical assistance as well as the Helmsley IBD Exomes Program and the groups that provided exome variant data for comparison. A full list of contributing groups can be found at http://ibd.broadinstitute.org/about.

Footnotes

Twitter: @KonradAden

LJ and KP contributed equally.

Contributors: LJ, KP, AS, MK, YZ, LM performed mouse experiments. LJ, MB, AH, RH, B-SL, KA, ML, AD performed gene expression analysis. TK performed EM analysis. AvM and AL performed cell death analysis. AN and GS generated and provided Setdb1fl/fl mice and contributed to the experimental design of experiments. TC and VN performed electrolyte, glucose and osmolality measurements. AL, SS, PCR, AF and JH contributed to supervision. SZ coordinated and supervised the study and wrote the manuscript with input from all coauthors.

Funding: This work was supported by the Histology Facility, the DRESDEN-concept Genome Center and the Electron and Light Microscopy Facilities of the CMCB Technology Platform at TU Dresden, the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) and the DFG Excellence Cluster ‘Center for Regenerative Therapies’ (to SZ), the DFG Cluster of Excellence 'Precision Medicine in Chronic Inflammation' (PMI, EXC2167) and DFG Project-ID 213249687—SFB 1064/TP11 and Project-ID 329628492—SFB1321/TP13 (to GS).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: All mice were handled and experiments conducted with the approval and in compliance with theinstitutional guidelines and respective authorities at the Technische Universität (TU) Dresden (DD24-5131/394/21). The human study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of Kiel University(reference B231/98-1/13).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Gehart H, Clevers H. Tales from the crypt: new insights into intestinal stem cells. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2019;16:19–34. 10.1038/s41575-018-0081-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Sousa e Melo F, de Sauvage FJ. Cellular plasticity in intestinal homeostasis and disease. Cell Stem Cell 2019;24:54–64. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.11.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Korinek V, Barker N, Moerer P, et al. Depletion of epithelial stem-cell compartments in the small intestine of mice lacking Tcf-4. Nat Genet 1998;19:379–83. 10.1038/1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Es JH, Haegebarth A, Kujala P, et al. A critical role for the Wnt effector Tcf4 in adult intestinal homeostatic self-renewal. Mol Cell Biol 2012;32:1918–27. 10.1128/MCB.06288-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kuhnert F, Davis CR, Wang H-T, et al. Essential requirement for Wnt signaling in proliferation of adult small intestine and colon revealed by adenoviral expression of Dickkopf-1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2004;101:266–71. 10.1073/pnas.2536800100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hermiston ML, Gordon JI. Inflammatory bowel disease and adenomas in mice expressing a dominant negative N-cadherin. Science 1995;270:1203–7. 10.1126/science.270.5239.1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ding L, Lu Z, Foreman O, et al. Inflammation and disruption of the mucosal architecture in claudin-7-deficient mice. Gastroenterology 2012;142:305–15. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. López-Posadas R, Becker C, Günther C, et al. Rho-A prenylation and signaling link epithelial homeostasis to intestinal inflammation. J Clin Invest 2016;126:611–26. 10.1172/JCI80997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Haber AL, Biton M, Rogel N, et al. A single-cell survey of the small intestinal epithelium. Nature 2017;551:333–9. 10.1038/nature24489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moor AE, Harnik Y, Ben-Moshe S, et al. Spatial reconstruction of single enterocytes uncovers broad zonation along the intestinal villus axis. Cell 2018;175:1156–67. 10.1016/j.cell.2018.08.063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kim T-H, Li F, Ferreiro-Neira I, et al. Broadly permissive intestinal chromatin underlies lateral inhibition and cell plasticity. Nature 2014;506:511–5. 10.1038/nature12903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dodge JE, Kang Y-K, Beppu H, et al. Histone H3-K9 methyltransferase ESET is essential for early development. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24:2478–86. 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2478-2486.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schultz DC, Ayyanathan K, Negorev D, et al. Setdb1: a novel KAP-1-associated histone H3, lysine 9-specific methyltransferase that contributes to HP1-mediated silencing of euchromatic genes by KRAB zinc-finger proteins. Genes Dev 2002;16:919–32. 10.1101/gad.973302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wang H, An W, Cao R, et al. mAM facilitates conversion by ESET of dimethyl to trimethyl lysine 9 of histone H3 to cause transcriptional repression. Mol Cell 2003;12:475–87. 10.1016/j.molcel.2003.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Loyola A, Tagami H, Bonaldi T, et al. The HP1alpha-CAF1-SetDB1-containing complex provides H3K9me1 for Suv39-mediated K9me3 in pericentric heterochromatin. EMBO Rep 2009;10:769–75. 10.1038/embor.2009.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hyun K, Jeon J, Park K, et al. Writing, erasing and reading histone lysine methylations. Exp Mol Med 2017;49:e324. e. 10.1038/emm.2017.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nicetto D, Donahue G, Jain T, et al. H3K9me3-heterochromatin loss at protein-coding genes enables developmental lineage specification. Science 2019;363:294–7. 10.1126/science.aau0583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dodge JE, Kang Y-K, Beppu H, et al. Histone H3-K9 methyltransferase ESET is essential for early development. Mol Cell Biol 2004;24:2478–86. 10.1128/MCB.24.6.2478-2486.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adoue V, Binet B, Malbec A, et al. The Histone Methyltransferase SETDB1 Controls T Helper Cell Lineage Integrity by Repressing Endogenous Retroviruses. Immunity 2019;50:629–44. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cuellar TL, Herzner A-M, Zhang X, et al. Silencing of retrotransposons by SETDB1 inhibits the interferon response in acute myeloid leukemia. J Cell Biol 2017;216:3535–49. 10.1083/jcb.201612160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kato M, Takemoto K, Shinkai Y. A somatic role for the histone methyltransferase SETDB1 in endogenous retrovirus silencing. Nat Commun 2018;9:1683. 10.1038/s41467-018-04132-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guler GD, Tindell CA, Pitti R, et al. Repression of stress-induced LINE-1 expression protects cancer cell subpopulations from lethal drug exposure. Cancer Cell 2017;32:221–37. 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pasquarella A, Ebert A, Pereira de Almeida G, et al. Retrotransposon derepression leads to activation of the unfolded protein response and apoptosis in pro-B cells. Development 2016;143:1788–99. 10.1242/dev.130203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Madison BB, Dunbar L, Qiao XT, et al. Cis elements of the villin gene control expression in restricted domains of the vertical (crypt) and horizontal (duodenum, cecum) axes of the intestine. J Biol Chem 2002;277:33275–83. 10.1074/jbc.M204935200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. el Marjou F, Janssen K-P, Chang BH-J, et al. Tissue-Specific and inducible Cre-mediated recombination in the gut epithelium. Genesis 2004;39:186–93. 10.1002/gene.20042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kontoyiannis D, Pasparakis M, Pizarro TT, et al. Impaired on/off regulation of TNF biosynthesis in mice lacking TNF AU-rich elements: implications for joint and gut-associated immunopathologies. Immunity 1999;10:387–98. 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80038-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wirtz S, Neufert C, Weigmann B, et al. Chemically induced mouse models of intestinal inflammation. Nat Protoc 2007;2:541–6. 10.1038/nprot.2007.41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tonnus W, Meyer C, Paliege A, et al. The pathological features of regulated necrosis. J Pathol 2019;247:697–707. 10.1002/path.5248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Peuker K, Muff S, Wang J, et al. Epithelial calcineurin controls microbiota-dependent intestinal tumor development. Nat Med 2016;22:506–15. 10.1038/nm.4072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sato T, van Es JH, Snippert HJ, et al. Paneth cells constitute the niche for LGR5 stem cells in intestinal crypts. Nature 2011;469:415–8. 10.1038/nature09637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zeissig S, Murata K, Sweet L, et al. Hepatitis B virus-induced lipid alterations contribute to natural killer T cell-dependent protective immunity. Nat Med 2012;18:1060–8. 10.1038/nm.2811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. DeLuca DS, Levin JZ, Sivachenko A, et al. RNA-SeQC: RNA-seq metrics for quality control and process optimization. Bioinformatics 2012;28:1530–2. 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu TD, Nacu S. Fast and SNP-tolerant detection of complex variants and splicing in short reads. Bioinformatics 2010;26:873–81. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Liao Y, Smyth GK, Shi W. featureCounts: an efficient General purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014;30:923–30. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-Seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 2014;15:550. 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ignatiadis N, Klaus B, Zaugg JB, et al. Data-Driven hypothesis weighting increases detection power in genome-scale multiple testing. Nat Methods 2016;13:577–80. 10.1038/nmeth.3885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Criscione SW, Zhang Y, Thompson W, et al. Transcriptional landscape of repetitive elements in normal and cancer human cells. BMC Genomics 2014;15:583. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Smit AFA, Hubley R, Green P. RepeatMasker Open-4.0. Available: http://www.repeatmasker.org

- 39. Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics 2010;26:139–40. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Häsler R, Sheibani-Tezerji R, Sinha A, et al. Uncoupling of mucosal gene regulation, mRNA splicing and adherent microbiota signatures in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut 2017;66:2087–97. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Planell N, Lozano JJ, Mora-Buch R, et al. Transcriptional analysis of the intestinal mucosa of patients with ulcerative colitis in remission reveals lasting epithelial cell alterations. Gut 2013;62:967–76. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Olsen J, Gerds TA, Seidelin JB, et al. Diagnosis of ulcerative colitis before onset of inflammation by multivariate modeling of genome-wide gene expression data. Inflamm Bowel Dis 2009;15:1032–8. 10.1002/ibd.20879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. Variation across 141,456 human exomes and genomes reveals the spectrum of loss-of-function intolerance across human protein-coding genes. bioRxiv 2019:531210. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kurth T, Weiche S, Vorkel D, et al. Histology of plastic embedded amphibian embryos and larvae. Genesis 2012;50:235–50. 10.1002/dvg.20821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kurth T, Berger J, Wilsch-Bräuninger M, et al. Electron microscopy of the amphibian model systems Xenopus laevis and Ambystoma mexicanum. Methods Cell Biol 2010;96:395–423. 10.1016/S0091-679X(10)96017-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hanker JS, Deb C, Wasserkrug HL, et al. Staining tissue for light and electron microscopy by bridging metals with multidentate ligands. Science 1966;152:1631–4. 10.1126/science.152.3729.1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ireland H, Houghton C, Howard L, et al. Cellular inheritance of a Cre-activated reporter gene to determine Paneth cell longevity in the murine small intestine. Dev Dyn 2005;233:1332–6. 10.1002/dvdy.20446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Röder PV, Geillinger KE, Zietek TS, et al. The role of SGLT1 and GLUT2 in intestinal glucose transport and sensing. PLoS One 2014;9:e89977. 10.1371/journal.pone.0089977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Ghaleb AM, McConnell BB, Kaestner KH, et al. Altered intestinal epithelial homeostasis in mice with intestine-specific deletion of the Krüppel-like factor 4 gene. Dev Biol 2011;349:310–20. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. van Es JH, Jay P, Gregorieff A, et al. Wnt signalling induces maturation of Paneth cells in intestinal crypts. Nat Cell Biol 2005;7:381–6. 10.1038/ncb1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ye DZ, Kaestner KH. Foxa1 and Foxa2 control the differentiation of goblet and enteroendocrine L- and D-cells in mice. Gastroenterology 2009;137:2052–62. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.08.059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wang R, Li H, Wu J, et al. Gut stem cell necroptosis by genome instability triggers bowel inflammation. Nature 2020;580:386–90. 10.1038/s41586-020-2127-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Karanth AV, Maniswami RR, Prashanth S, et al. Emerging role of SETDB1 as a therapeutic target. Expert Opin Ther Targets 2017;21:319–31. 10.1080/14728222.2017.1279604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rivas MA, Avila BE, Koskela J, et al. Insights into the genetic epidemiology of Crohn's and rare diseases in the Ashkenazi Jewish population. PLoS Genet 2018;14:e1007329. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1007329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2020-321339supp001.xlsx (12.1KB, xlsx)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp005.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp006.pdf (1.5MB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp007.pdf (348.4KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp008.pdf (9.2MB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp009.pdf (91.3KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp010.pdf (1.9MB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp002.xlsx (20.4KB, xlsx)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp011.pdf (432.6KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp003.xlsx (71.8KB, xlsx)

gutjnl-2020-321339supp004.xlsx (47.6KB, xlsx)