Abstract

Fascin actin-bundling protein 1 (FSCN1) is a highly conserved actin-bundling protein that cross links F-actin microfilaments into tight, parallel bundles. Elevated FSCN1 levels have been reported in many types of human cancers and have been correlated with aggressive clinical progression, poor prognosis, and survival outcomes. The overexpression of FSCN1 in cancer cells has been associated with tumor growth, migration, invasion, and metastasis. Currently, FSCN1 is recognized as a candidate biomarker for multiple cancer types and as a potential therapeutic target. The aim of this study was to provide a brief overview of the FSCN1 gene and protein structure and elucidate on its actin-bundling activity and physiological functions. The main focus was on the role of FSCN1 and its upregulatory mechanisms and significance in cancer cells. Up-to-date studies on FSCN1 as a novel biomarker and therapeutic target for human cancers are reviewed. It is shown that FSCN1 is an unusual biomarker and a potential therapeutic target for cancer.

Keywords: FSCN1, cancer, biomarker, therapeutic target, metastasis

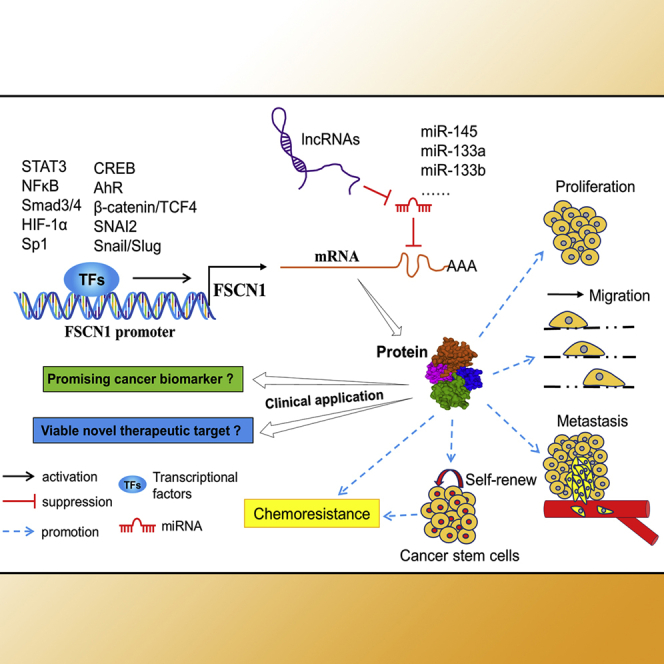

Graphical Abstract

As an actin-bundling protein, FSCN1 plays an important role in cancer progression and metastasis. Its expression has been correlated with an aggressive clinical course and poor prognosis. This review summarizes not only the role of FSCN1 in cancers but also its clinical application in cancer therapy by targeting FSCN1.

Main text

Fascin actin-bundling protein 1 (FSCN1), also known as fascin1 or fascin, is a globular filamentous actin-binding protein of the fascin family.1,2 By stabilizing actin bundles, FSCN1 supports a variety of cellular structures, including microspikes, filopodia, lamellipodia, and other actin-based protrusions underneath the plasma membrane.3 These structures are essential in cellular migration, cell-matrix adhesion, and cell-to-cell interactions. In healthy adult tissues, FSCN1 expression is restricted to the neuronal, endothelial, mesenchymal, and dendritic cells4 and is absent or at low levels in normal epithelial cells.3 FSCN1 has been shown to be unusually expressed in transformed epithelial cells and many human cancers. This implies that it may functionally contribute toward cancer progression.

Recently, FSCN1 has received a lot of attention, because multiple studies have implicated it as a candidate biomarker or therapeutic target for aggressive, metastatic carcinomas of many cancer types.1,3,5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Functional studies have revealed that FSCN1 promotes tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis.1,8,10 In addition, its overexpression is involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) that confers tumor cells with motility and invasive properties.11 Immunohistochemical (IHC) studies have demonstrated that FSCN1 protein expression is correlated with clinically aggressive phenotypes, poor prognosis, and survival outcomes.1,5,11,12 Systematic reviews and meta-analyses have revealed that FSCN1 is correlated with increased mortality risks and metastasis in various cancer types, is a novel biomarker for the identification of aggressive and metastatic tumors,12 and is a prognostic marker of overall survival.13 Targeted inhibition of FSCN1 functions with small molecule inhibitors blocking tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis.7,8,14,15 This shows the potential of FSCN1 as a therapeutic target.

In this study, we review the FSCN1 gene and protein structure, its regulation of actin-bundling activity, and its physiological functions. The main focus was on the role of FSCN1 and its upregulatory mechanisms and significance in cancer cells. Up-to-date studies on FSCN1 as a novel biomarker and therapeutic target for human cancers are reviewed. It is shown that FSCN1 is an unusual biomarker and a potential therapeutic target for cancer.

FSCN1 structure and activity regulation

FSCN1 gene and protein structure

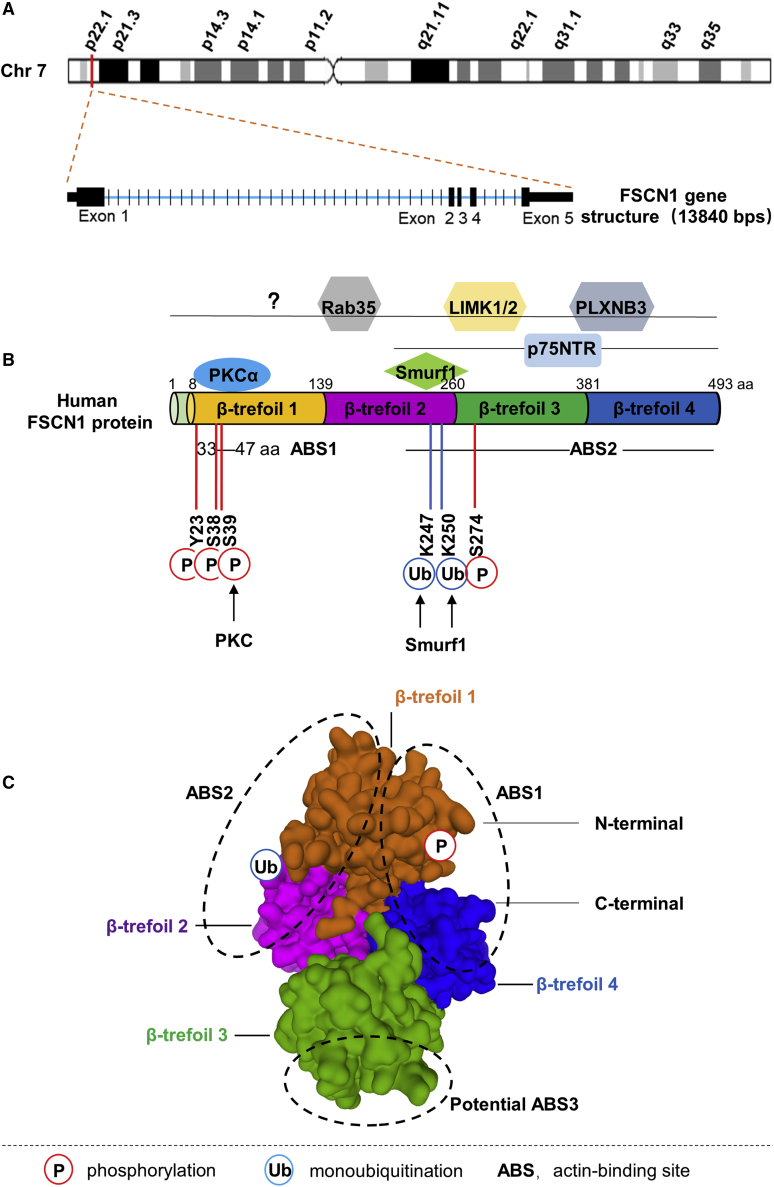

The human FSCN1 gene (GenBank: NM_003088.4) is located on chromosome 7p22.1, containing 5 exons, 13,840 bp in length (Figure 1A). The orthologs of the human FSCN1 gene are found in 224 organisms, and the FSCN1 gene is conserved in chimpanzee, dog, cow, mouse, rat, chicken, zebrafish, and frog. The nucleotide sequence of the human FSCN1 gene is highly homologous with mouse (96.55%) and zebrafish (75.76%), suggesting that FSCN1 is likely to have fundamentally critical biological functions.

Figure 1.

FSCN1 gene and protein structure, post-translational modifications, and interactions

(A) Schematic of the FSCN1 gene that is located at chromosome 7p22.1 and is about 13.84 kb long, containing 5 exons (represented in black blocks). (B) Schematic diagram for human FSCN1 protein structure, post-translational modifications, and interactions. FSCN1 consists of four highly conserved β-trefoil domains. Actin-binding site 1 (ABS1) is located at the amino terminus, in the β-trefoil 1 domain between amino acids (aa) 33 and 47, whereas the ABS2 is predicted to locate at the carboxyl terminus, in the region near serine 274 (S274). Post-translational modification sites of FSCN1 are indicated below the FSCN1 structure: P, phosphorylation (in red) and S39 (in C); Ub, monoubiquitination (in blue) and lysine (K)247 and K250 (in C). FSCN1-interacting proteins that regulate its activity or function are represented above FSCN1 at their described binding site. (C) Surface presentation of the human FSCN1 (PDB: 3P53). The four β-trefoil domains are highlighted with different colors. Three ABSs (ABS1−3), identified from systematic mutagenesis studies, are also shown.

The human FSCN1 protein (GenBank: NP_003079.1) is a 493-amino acid (aa)-long protein with a molecular mass of 54.5 kDa. It is comprised of four tandem β-trefoil domains (residues 8–139, 140–260, 261–381, and 382–493) (Figure 1B). The X-ray crystal structure of human FSCN1 revealed that the four β-trefoil domains are arranged as two skewed lobes, corresponding to β-trefoil 1 and 2 and β-trefoil 3 and 4, respectively.16, 17, 18 One actin-binding site (ABS) has been shown to be located at the β-trefoil 1 domain between aa 33 and 47 in human FSCN1,16,19 whereas the second ABS has not yet been fully mapped. However, its location has been postulated to be at the region near serine 274 (Ser274) in human FSCN1 (Figure 1B).16,20 Recent studies have uncovered that there are three ABSs (ABS1−3) on the three distinct surface areas of the FSCN1 molecule17,21 (Figure 1C). The ABS1 is formed by residues from the N and C termini of FSCN1 and includes the cleft formed by β-trefoil 1 and 4.17 This region includes a highly conserved site (Ser39) that can be phosphorylated by protein kinase C (PKC).19,22,23 The ABS2 contrasts to ABS1 and includes residues from β-trefoil 1 and 2. The ABS3 is a potential site that involves β-trefoil 3.17 Therefore, all four β-trefoil domains of FSCN1 are involved in actin bundling.

Regulation of FSCN1 activity

FSCN1 is an evolutionarily conserved actin-bundling protein, in which its primary function is to cross link actin microfilaments into tight, relatively rigid, parallel bundles.24 The actin-bundling activity of FSCN1 is fundamentally linked to its structure and is regulated by a variety of factors, such as post-translational modifications,20,22,25, 26, 27 interaction partners,19,22,27, 28, 29, 30, 31 and small molecule compounds.7,8,14,32, 33, 34

Post-translational modifications of FSCN1 regulate its actin-bundling activity and function.22,25, 26, 27 Yamakita et al.25 demonstrated that phosphorylation of human FSCN1 inhibits its actin-binding and -bundling activities. The best-characterized phosphorylation site of FSCN1 is a conserved serine, Ser39, at its ABS1 that can be phosphorylated by PKC (Figure 1B).19,22 Evidence shows that Ser39 is associated with phosphorylation-dependent regulation of FSCN1 actin binding.20,22,26,35 In addition to Ser39, multiple phosphorylation sites on FSCN1 are involved in its actin-bundling activity. Zanet et al.20 documented that Ser274 can be phosphorylated to modulate the actin-bundling capacity of FSCN1 in human cancer cells. These findings are consistent with the characterization of an actin-binding domain of FSCN1 located in the region surrounding Ser274.18 In addition, Zeng et al.35 reported that phosphorylation of FSCN1 at tyrosine 23 and Ser38 is important in cell migration and filopodia formation in esophageal squamous cancer cells. Therefore, the balance between FSCN1 phosphorylation/dephosphorylation is important in the regulation of its activity. The regulatory mechanisms for FSCN1 phosphorylation/dephosphorylation have not been established; however, Ser39 phosphorylation is regulated by PKC and neurotrophin nerve growth factor.

Monoubiquitination is a post-translational modification that regulates FSCN1 actin-bundling activity and dynamics. Lin et al.27 revealed that FSCN1 was monoubiquitinated at two lysine residues (Lys247 and Lys250) in its ABS2. The E3 ubiquitin ligase Smurf1, which has been reported to interact with FSCN1, is partially responsible for catalyzing FSCN1 monoubiquitination. Moreover, they also revealed that monoubiquitination at ABS2 inhibited FSCN1 bundling activity by introducing steric hindrance to interfere with the interactions between FSCN1 and actin filaments.27 In addition to phosphorylation and monoubiquitination, the functional roles of other FSCN1 modifications, such as acetylation and methylation, have not been established.

Multiple FSCN1 interaction partners, including PKCα, Smurf1, plexin-B3 (PLXNB3), p-Lin-11/Isl-1/Mec-3 (LIM) kinases 1 and 2 (LIMK1/2), p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75NTR), and Rab35, regulate its activity or function (Figure 1B).19,22,27, 28, 29, 30, 31 Anilkumar et al.19 revealed that FSCN1 is a substrate and a binding partner of PKCα. They also showed that FSCN1-PKCα interactions occur dynamically in migrating cells and are important in the regulation of actin-crosslinking activity of FSCN1.19 Smurf1 is a E3 ubiquitin ligase that is essential in regulating the monoubiquitination of FSCN1.27 FSCN1 interacts with PLXNB3, the known functional receptor of Sema5A to mediate Sema5A-induced FSCN1 phosphorylation and actin network remodeling.30 It has also been reported that FSCN1 and LIMK1/2 form a complex that regulates the interactions of FSCN1 with actin and the stability of filopodia.31 FSCN1 interaction with p75NTR is fascinating. This is because it is involved in the direct recruitment of FSCN1 to the plasma membrane, where it is dephosphorylated at Ser39 by neurotrophin nerve growth factor.28 In addition, Zhang et al.29 revealed that Rab35 directly associates with fascin and regulates the assembly of actin filaments during filopodia formation in cultured cells by recruiting fascin as an effector protein. In addition to the above interaction partners, various proteins have been found to physiologically interact with FSCN1.36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41 However, it has not been established if these interactions regulate the actin-bundling activity of FSCN1.

The role of FSCN1 in tumor cell migration and invasion has been correlated to its actin-bundling activity. Therefore, various small molecule compounds that target FSCN1 and inhibit its activity have been recently identified.7,8,14,32,33 Chen et al.7 demonstrated that the metastasis inhibitory small molecules (migrastatin analogs) inhibit FSCN1 activity by binding to one of its ABSs. With the use of high-throughput screening, Huang and coworkers8,14 screened chemical libraries and identified small molecule compounds that specifically inhibited FSCN1 from bundling actin. They revealed that the small molecule compound G2 inhibits the actin-bundling function of FSCN1 and blocks tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. In addition, a series of thiazole derivatives has also been reported to inhibit metastatic cancer cell migration and invasion by interfering with the actin-bundling function of FSCN1.32,33 However, the mechanisms by which thiazole derivatives regulate FSCN1 activity have not been elucidated.

The physiological function of FSCN1

FSCN1 is an actin-bundling protein that organizes actin filaments into parallel bundles. Therefore, it is involved in a broad range of cellular physiological processes, including regulation of cell adhesion, motility, migration, and cellular interactions.2,42,43 In addition, FSCN1 regulates focal adhesion dynamics,44 cell migration and invasion,36,38,45 histone methylation and gene transcription,46 extracellular vesicle release,47 and cancer cell stemness,38,48,49 independently of its actin-bundling activity. We review the actin-dependent and -independent functions of FSCN1 in this study.

Actin-dependent functions

As an actin-bundling protein, FSCN1 bundles or cross links actin filaments through three binding sites and is involved in the formation, as well as in the stability, of a wide range of cellular protrusions.17,50, 51, 52 Many of these FSCN1-containing protrusions, such as microspikes, filopodia, and lamellipodia, are transient, dynamic, and functionally required for cell adhesions, interactions, motility, and migration.2,42,43 Adams,53,54 in 1995 and 1997, respectively, revealed that the assembly of fascin microspikes is of functional significance for cell adhesion to specific extracellular matrix macromolecules. By interacting with active PKC that phosphorylates it on Ser39 and inhibits FSCN1/actin binding, FSCN1 is involved in cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix.19 Additionally, it has been shown that FSCN1 regulates focal adhesion dynamics in a variety of cell types. This regulation is partially dependent on its canonical actin-bundling function.44,55, 56, 57 FSCN1-containing protrusions are also important in cell interactions. For example, in breast epithelial tumor cells, fascin spikes play a role in sensing and responding to the extracellular insulin-like growth factor 1 stimulation.58 In dendritic cells, the large FSCN1-containing dendrites mediate effective interactions and antigen presentation to T cells.59

FSCN1 has been reported to play an important role in the regulation of cell motility and migration, which function in normal embryonic development and tumor progression.1, 2, 3,60 FSCN1 controls a variety of critical cell motility processes, such as directed cell migration, neurite or growth cone extension, and dendrite formation during normal development.60, 61, 62, 63, 64 When FSCN1 is expressed in the above processes, its effects on actin-filament structures are responsible for the enhancement of cell motility. Furthermore, FSCN1 is also highly expressed in many types of tumors (reviewed in Machesky and Li11) and promotes tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. This elevates mortality risks.1,12,55 Although novel actin-independent roles of FSCN1 have been discovered,36,38,45 they do promote tumor cell migration and invasion through the formation of filopodia and invadopodia.11,17,42,52

Actin-independent functions

In addition to bundling actin, FSCN1 has multiple actin-bundling-independent cellular functions. Villari et al.44 documented that FSCN1 controls focal adhesion dynamics and cell migration by directly binding to microtubule cytoskeleton. The disruption of the interactions between FSCN1 and microtubules enhances cellular adhesion stability and decreases cell migration44. Moreover, the stimulatory effect of FSCN1 hyperexpression on breast cancer cell metastasis is dependent on the enhancement of microtubule dynamics, not its actin-bundling activity.45 FSCN1 interacts with the nuclear envelope protein nesprin-2 through a direct, actin-independent mechanism. This interaction is important for nuclear deformation and movement during cell-invasive migration.36 Additionally, FSCN1 maintains or increases cancer cell stemness in melanoma and breast cancer stem cells (CSCs), independently of its actin-bundling activity.38,48,49

Recently, several novel actin-independent roles of FSCN1 have been reported. Saad et al.46 revealed that phosphorylated fascin 1 (pFascin) is primarily localized in the nucleus and regulates histone methylation and gene transcription. pFascin specifically interacts with the H3K4 methyltransferase core subunit RbBP5 form H3K4me3. Nuclear pFascin interactions with the RNA polymerase II complex elucidate on the role of fascin in transcription.46 Lin et al.65 showed that FSCN1 promotes lung cancer metastatic colonization by augmenting metabolic stress resistance and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation. An additional actin-independent role of FSCN1 is the control of extracellular vesicle release. Beghein et al.47 showed that FSCN1 regulates extracellular vesicle release presumably depending on its microtubule-regulating function, independently of its actin-bundling activity. Clancy et al.66 documented that coordinated regulation of intracellular FSCN1 distribution is important for tumor microvesicle release. In addition, Lam et al.63 have also documented an actin-independent role of fascin in border cell migration during Drosophila oogenesis. It regulates delamination during border cell migration by altering E-cadherin localization in the border cells.

In summary, FSCN1 is a multifunctional protein that plays an important role in regulating various cellular physiological processes in normal and tumor cells. Most of these processes, particularly tumor cell migration and metastasis, are attributed to its actin-dependent and actin-independent functions. However, it has not been established whether the two distinct functions of FSCN1 synergistically regulate migration and metastasis or not. Elucidation of FSCN1 regulatory mechanisms in certain cancer types is important for the development of targeted therapeutic agents.

Role of FSCN1 in cancer

FSCN1 is associated with cell motility. In 2000, the first report on the analysis of FSCN1 in human breast cancer was published.67 It was shown that FSCN1 upregulation enhances the aggressiveness of human breast cancer. After that, a series of studies has shown that FSCN1 is highly expressed in different cancer types and that its expression is associated with aggressive clinical course, poor prognosis, and shorter survival outcomes.1,3,9,11,12 Functional studies using human cancer cell lines have shown that FSCN1 is involved in the regulation of cancer-related cellular properties, such as growth, migration, invasion, metastasis, and therapeutic resistance. The essential findings are summarized in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

The biological effects on downregulation of FSCN1 in vitro experiments

| Cancer type | Cell lines | Proliferation | Growth | Migration and invasion | Metastasis | Drug resistance | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bladder cancer | T24 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 68 |

| T24, BIU87 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 69 | |

| 5637, BIU87 | no effect | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 70 | |

| Breast cancer | Bcap-37, HCC-1937, MDA-MB-468, MDA-MB-231 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 71,72 |

| MCF-7, MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-231 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 73,74 | |

| MDA-MB-231 | unknown | unknown | unknown | unknown | decrease resistance to doxorubicin | 75 | |

| MDA-MB-231 | no effect | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 76 | |

| Cervical cancer | HeLa | inhibited | unknown | unknown | unknown | unknown | 77 |

| CaSki | inhibited | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 78 | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | QBC939 | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | unknown | unknown | 79 |

| Chondrosarcoma | JJ012, SW1353 | no effect | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 80 |

| Colorectal cancer | SW480Pa, IKD-F11 | unknown | inhibited | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | 55 |

| SW480, HCT116, SW620, LoVo, HT-29 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 81, 82, 83, 84 | |

| SW480 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 85 | |

| Esophageal cancer | KYSE 170 | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | unknown | unknown | 86 |

| KYSE 150, T.Tn, TE2 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 87,88 | |

| KYSE-30 | inhibited | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 89 | |

| Gastric cancer | SGC-7901 | inhibited | unknown | unknown | unknown | unknown | 90 |

| MGC-803, SGC-7901 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 91 | |

| HGC-27, MGC-803, MKN-28, AGS | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 92, 93, 94 | |

| MKN45 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | inhibit liver metastasis | unknown | 95 | |

| MKN45 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | 96 | |

| SGC-7901, MKN45 | unknown | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 97 | |

| Glioma | U251, U87, SNB19 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 98 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | SNU449, SNU387, Huh7, Hep3B | inhibited | unknown | unknown | unknown | decrease resistance to doxorubicin | 99 |

| HLE | no effect | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 100 | |

| Laryngeal cancer | Hep-2, TU-177 | inhibited | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 101 |

| Lung cancer | SPC-A1, H1299 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | decrease resistance to docetaxel | 102 |

| H1650 | no effect | unknown | unknown | unknown | unknown | 65 | |

| H292 | unknown | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | 65 | |

| Melanoma | BLM, FM3P, WM793 | no effect | unknown | no-effect cell migration; enhance cell invasion |

unknown | unknown | 103 |

| Nasopharyngeal carcinoma | SUNE-1, CNE-2, 5-8F, CNE1 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 104,105 |

| SUNE-1, CNE-2 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 106 | |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | A549, H520, SPC-A-1 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 107,108 |

| H1229, H129 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 109,110 | |

| Oral cancer | HSC-3, SCC-15 | no effect | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 111 |

| OEC-M1, SCC-25 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 112 | |

| Ovarian cancer | SKOV3, 3AO | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 39,113 |

| SKOV3, OVCAR3 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 114 | |

| HeyA8, Ovcar5, Tyk-nu | unknown | unknown | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | 115 | |

| Pancreatic cancer | MIA PaCa-2 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 116 |

| Prostate cancer | PC3, DU145 | inhibited | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 117 |

| DU145 | unknown | inhibited | inhibited | inhibit lymph node metastasis | unknown | 10 | |

| Renal cancer | 769-P, OSRC, 786-0 | unknown | unknown | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 118,119 |

| A498, 786-O | unknown | unknown | inhibited | inhibit lung metastasis | unknown | 120 | |

| Tongue cancer | CAL-27, SCC-25 | inhibited | inhibited | inhibited | unknown | unknown | 121 |

Table 2.

The biological effects on upregulation of FSCN1 in vitro experiments

| Cancer type | Cell lines | Proliferation | Growth | Migration and invasion | Metastasis | Drug resistance | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast cancer | MDA-MB-468, MDA-MB-231 | unknown | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 71,122 |

| MDA-MB-231 | no effect | no effect | no effect | enhance lung metastasis | unknown | 45 | |

| MDA-MB-231 | no effect | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 76 | |

| T47-D, SK-BR-3 | unknown | unknown | unknown | unknown | increase resistance to doxorubicin | 75 | |

| MDA-MB-435, MDA-MB-231 | enhanced | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 73 | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | RBE | enhanced | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 123 |

| Colorectal cancer | AAC1, ANC1, RGC2, HT-29, SW620, LoVo | unknown | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 82,124 |

| HT-29 | unknown | unknown | enhanced | enhance lung metastasis | unknown | 81 | |

| Esophageal cancer | SHEE | enhanced | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 88 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | Huh7, SK-HEP1 | unknown | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 100,125 |

| Hypopharyngeal cancer | FaDu | unknown | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 126 |

| Lung cancer | SPC-A1, H1299 | enhanced | unknown | enhanced | unknown | increase resistance to docetaxel | 102 |

| Non-small cell lung cancer | A549, SPC-A-1 | enhanced | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 107 |

| A549 | no effect | no effect | enhanced | enhanced | unknown | 127 | |

| Oral cancer | AW13516 | enhanced | enhanced | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 128 |

| Osteosarcoma | SaOS-2, 143B | unknown | enhanced | enhanced | enhance lung metastasis | unknown | 129 |

| Ovarian cancer | SKOV3, 3AO | unknown | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 39 |

| Pancreatic cancer | MIA PaCa-2 | no effect | unknown | enhanced | enhance skin metastasis | unknown | 130 |

| MIA PaCa-2 | unknown | unknown | enhanced | unknown | unknown | 116 | |

| Prostate cancer | PC3, DU145 | unknown | unknown | unknown | unknown | increase resistance to paclitaxel | 131 |

Upregulation of FSCN1 expression in cancer

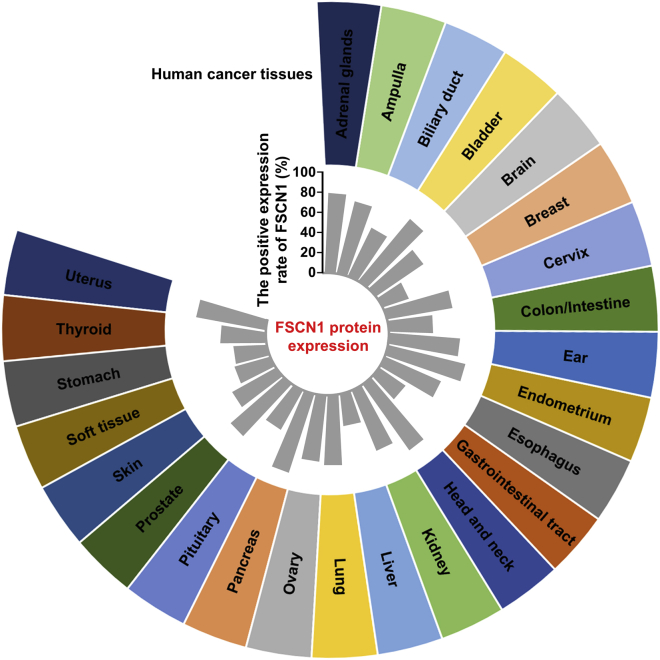

The absence or low expression of FSCN1 in normal epithelia is altered in different human carcinomas. To date, more than 100 studies were published on FSCN1 expression in tumors and malignancies from various tissues and organs examined by IHC, tissue microarray, qPCR, or western blot analysis (summarized in Table S1). In nearly all cancers, the positive expression rate of FSCN1 was increased in cancer tissues compared to that in normal epithelium or para-carcinoma tissues. Evidence shows that there are tissue-specific mechanisms that regulate FSCN1 expression. This explains why the various proportions of FSCN1 in FSCN1-positive tumors, detected in different human tissues, vary significantly (Figure 2). For example, more than 80% of bladder, as well as head and neck cancer tissues, express high levels of FSCN1. However, in breast or gastric cancer tissues, the average frequency of FSCN1 upregulation is 27% and 33%, respectively (Figure 2; Table S1). Pelosi et al.132 showed that FSCN1 immunoreactivity was detected in 5% of typical carcinoids, 35% of atypical carcinoids, 83% of large-cell neuroendocrine carcinomas, and 100% of small-cell lung carcinomas, even though they are all lung tumors. The frequency of FSCN1-positive expression has been established to be higher in most clinically aggressive tumors. In breast and kidney cancer, the frequency of FSCN1-positive tumors tended to increase with tumor invasion and metastasis.71,133 In addition, in the squamous cell carcinoma, especially head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, FSCN1 upregulation is frequently high (Table S1).

Figure 2.

Expression of FSCN1 protein in different human cancer tissues

The average positive rate of FSCN1 protein expression in different types of human cancer tissues is shown in the center of the figure.

FSCN1 upregulation mechanisms in cancer

Several studies have been aimed at understanding the molecular basis for elevated FSCN1 protein expression levels in human cancers. The regulation of FSCN1 expression in cancers is challenging and is affected by both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Studies have also shown that alterations in gene copy numbers are not associated with FSCN1 upregulation.

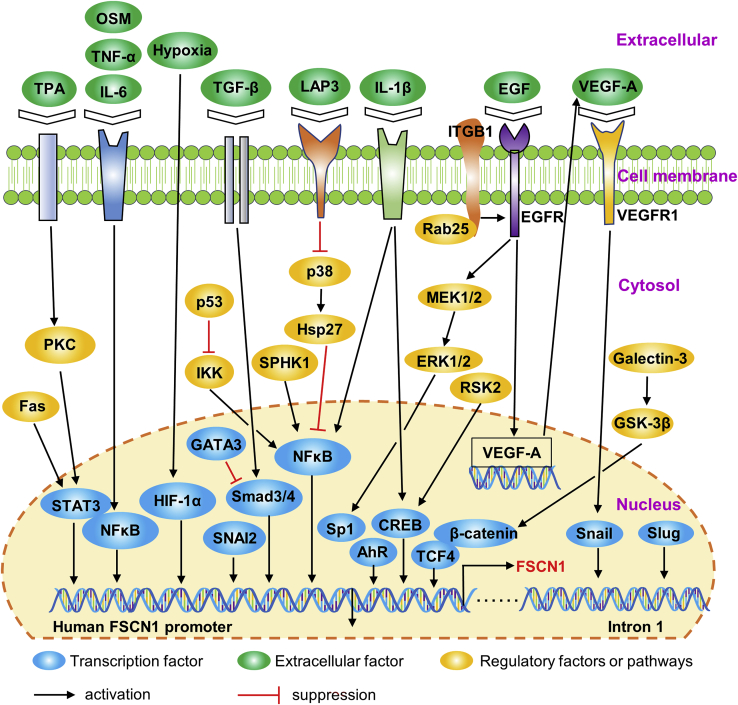

Transcriptional factors (TFs) and related signaling pathways. Mechanisms of transcriptional regulation for FSCN1 in human cancers have been studied. As shown in Figure 3, multiple TFs bind FSCN1 gene promoter regions and play an important role in regulating FSCN1 transcription. Different regulatory factors and signaling pathways regulate FSCN1 expression by activating TFs in different cancer cell types (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Transcriptional regulation of FSCN1 in human cancer

Multiple transcriptional factors bind to the promoter regions of the FSCN1 gene. Regulatory factors or signaling pathways that regulate FSCN1 expression by activating the transcriptional factors are also shown.

FSCN1 is regulated by the cyclic AMP (cAMP) response element-binding protein (CREB)-binding protein in NT2 neuronal precursor cells.134 Hashimoto et al.135 documented that the transcriptional activity of FSCN1 is regulated by a promoter region (−219/+114).

They also showed that CREB and aryl hydrocarbon receptors (AhRs) specifically associate with the −219/+114 region of the FSCN1 promoter in FSCN1-positive human breast and colon cancer cells. Li et al.136 found that the expression of FSCN1 can be suppressed by p90 ribosomal S6 kinase 2 (RSK2) knockdown in cell lines from diverse human cancers in a CREB-dependent manner. A recent study established that the CREB signaling pathway is involved in interleukin (IL)-1β-induced FSCN1 expression in human oral cancer cells.137

In addition, the β-catenin-T cell factor (TCF; TF) signaling pathway is involved in the regulation of FSCN1 transcription in human colorectal cancer cells,81 whereas galectin-3 enhances the expression of FSCN1 in human gastric cancer cells by regulating the glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK)-3β/β-catenin/TCF-4 signaling pathway.92 However, some studies do not support the hypothesis that the β-catenin-TCF pathway has a specific role in regulating FSCN1 transcriptional activity in human MDA-MB-435 cells or in fascin-positive human colon cancer cells.135,138 It has not been established whether the expression of FSCN1 in human cancers is regulated by β-catenin-TCF signaling.

FSCN1 is specifically regulated by TF specificity protein 1 (Sp1) in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC).139 Sp1 upregulates FSCN1 transcription by binding to the key element located at −70 to −60 nt of the FSCN1 promoter. It was also observed that stimulation with epidermal growth factor (EGF) enhanced FSCN1 expression. This inductive effect exerted by EGF was found to be dependent on the activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK)-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 (ERK1/2)-Sp1 signaling pathway.139

Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) are two well-known TFs required for the cytokine-induced expression of FSCN1 in human cancer cells.140, 141, 142, 143, 144 FSCN1 expression is induced by a variety of cytokines, such as IL-6, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, and oncostatin M (OSM). These cytokines activate STAT3 and NF-κB in human breast and gastric cancer cells to induce the expression.140, 141, 142 A 160-bp conserved region of the FSCN1 promoter has been shown to contain overlapping STAT3 and NF-κB sites.140 STAT3 and NF-κB are co-dependent in their binding to the FSCN1 promoter in response to cytokine treatment.140, 141, 142 In addition to cytokines, several signaling pathways regulate FSCN1 expression by activating STAT3 or NF-κB. Yang et al.145 revealed that Fas signaling promotes FSCN1 expression by activating STAT3 in AGS gastric cancer cells. 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol 13-acetate (TPA)-induced FSCN1 gene transcription is partially mediated by the PKCδ/STAT3α signaling pathway in MCF-7 breast cancer cells.144 In addition, p53 suppresses FSCN1 expression by inhibiting NF-κB signals in colorectal cancer cells.146 Fang et al.147 reported that leucine aminopeptidase 3 promotes FSCN1 expression through the p38-Hsp27-NF-κB signaling pathway. It has also been reported that FSCN1, in triple-negative breast cancer, is transcriptionally upregulated by sphingosine kinase 1, which activates NF-κB.148

The expression of FSCN1 can be enhanced by transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β) treatment in spindle-shaped tumor cells in a Smad-dependent manner.149 Depletion of TF Smad3 or Smad4 by short hairpin (sh)RNA was shown to inhibit TGF-β-induced FSCN1 expression in human MDA-MB-231 cells and A549 cells.149 The luciferase reporter assay demonstrated that the Smad4 transcription complex promoted FSCN1 expression by directly binding to the −370 CAGAC site of the FSCN1 promoter.150 In breast cancer cells, GATA3 inhibits Smad4-mediated FSCN1 overexpression by suppressing the binding of Smad4 to the FSCN1 promoter.150 In gastric cancer, the induction of FSCN1 expression by TGF-β is partially dependent on Smad3 linker phosphorylation.151

Hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) is a TF that has been implicated in FSCN1 expression. It is required for hypoxia-induced overexpression of FSCN1 in pancreatic and hypopharyngeal cancer cells.116,126 HIF-1α knockdown by specific small interfering RNA (siRNA) was shown to suppress the expression of FSCN1 under hypoxia.116,126 Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis revealed that FSCN1 is a direct target gene for HIF-1α. Hypoxic microenvironments upregulate FSCN1 expression by enhancing the binding of HIF-1α to a hypoxia response element on the FSCN1 promoter and transactivating FSCN1 transcription.116

Evidence suggests that snail family TFs are involved in the regulation of FSCN1 transcription. Li et al.152 reported that the expression of snail or slug (also called snail2) in human pancreatic cancer cells PANC-1 and human colon cancer cells HT29 induced FSCN1 expression. They found a conserved slug-binding E-box sequence located within the first intron of the mammalian fascins. slug co-precipitated with this putative fascin E-box element in mouse pancreatic cancer cells.152 Wang et al.153 documented that snail family transcriptional repressor 2 (SNAI2) elevates the expression of FSCN1 at both mRNA and protein levels in head and neck cancer cells by binding the FSCN1 promoter. In addition, Jeong et al.154 demonstrated that a integrin β1 (ITGB1)/EGF receptor (EGFR)/vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-A/VEGF receptor (VEGFR)-1/snail signaling axis is critical for Rab25-induced cancer cell aggressiveness through induction of FSCN1 expression.

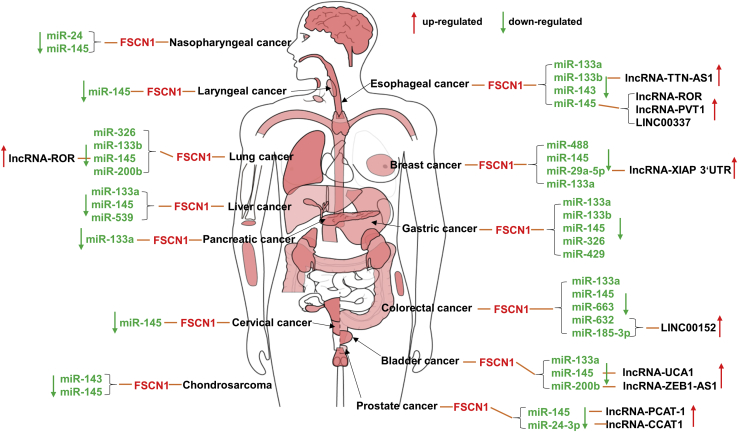

MicroRNAs (miRNAs and miRs) and long-noncoding RNAs (lncRNAs). Many miRNAs bind the 3′ UTR of the FSCN1 transcript and lead to negative regulation. As shown in Figure 4, miR-145 negatively regulates FSCN1 mRNA levels in many different human cancers, including nasopharyngeal, laryngeal, esophageal, breast, lung, stomach, liver, colon, bladder, cervix, prostate, and cartilage cancers.72,77,80,82,101,104,109,117,156, 157, 158, 159 miR-133a/b directly targets FSCN1 in a variety of human cancers and acts as a tumor suppressor.87,93,158,160, 161, 162, 163, 164 Furthermore, the FSCN1 gene has been identified as a direct target of several miRNAs, such as miR-143 in chondrosarcoma and esophageal carcinoma,80,165 miR-24 in nasopharyngeal and prostate cancer,106,131 miR-326 in lung and gastric cancer,166,167 and so on (summarized in Figure 4). All of the above-mentioned miRNAs were, however, significantly downregulated in corresponding human cancer specimens or cell lines and exerted their anti-tumor functions through a coordinated regulation of FSCN1.

Figure 4.

Regulation of FSCN1 expression by miRNAs and long-noncoding RNAs in different human cancers

The body map of FSCN1 expression in tumors reproduced from Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA).155

Cancer-associated lncRNAs compete endogenous RNA (ceRNA) in the regulation of FSCN1 expression through miRNAs. Xue and colleagues159 reported that lncRNA-UCA1 mediates bladder cancer progression through the miR-145-FSCN1 pathway. Different studies have confirmed this finding. As shown in Figure 4, the functions of lncRNA-regulatory of reprogramming (ROR) in lung and esophageal cancer depend on the sponging of miR-145, thereby upregulating the expression of FSCN1.102,156 Moreover, lncRNA-PVT1, lncRNA-PCAT-1 and long intergenic noncoding RNA (LINC)00337 also act as ceRNA of miR-145 in esophageal and prostate cancer.168, 169, 170 In addition, lncRNA-TTN-AS1 enhances FSCN1 expression by competitively binding to miR-133b in esophageal cancer.160 Wu et al.171 showed that lncRNA-XIAP-3′ UTR antagonizes miR-29a-5p, resulting in the increased translation of FSCN1 in breast cancer. Gao et al.172 found that lncRNA-ZEB1-AS1 functions as a ceRNA in bladder cancer and regulates the expression of FSCN1 through miR-200b. It has recently been established that LINC00152 regulates FSCN1 by sponging with miR-632 and miR-185-3p in colorectal cancer.173 lncRNA-CCAT1 interference contributes to the sensitivity of paclitaxel by regulating miR-24-3p and FSCN1.131 With the advances in high-throughput RNA deep sequencing, it is postulated that additional lncRNAs involved in regulating FSCN1 will be revealed.

Two miRNAs (miR-146a and miR-451) do not regulate FSCN1 expression by binding the 3′ UTR of the FSCN1 transcript. Kanda et al.174 revealed that stable FSCN1 expression in colon adenocarcinoma cells is induced by the inhibition of proteasome degradation by miR-146a. Chen et al.83 found that miR-451 was overexpressed in colorectal cancer cells, thereby inhibiting AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) from activating mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) complex 1 (mTORC1) that promotes FSCN1 expression.

The above-discussed molecular mechanisms are known for enhancing FSCN1 expression by cancer cells. There are multiple mechanisms for FSCN1 upregulation in human cancers. Although the upregulation of FSCN1 has been extensively studied in many different cancer cells—several regulatory factors or signaling pathways regulate FSCN1 expression—their underlying mechanisms have not been established. Therefore, integrated studies of these mechanisms in same cell types are needed to better understand the complex regulation of FSCN1 expression.

Functional consequences of FSCN1 upregulation in cancer cells

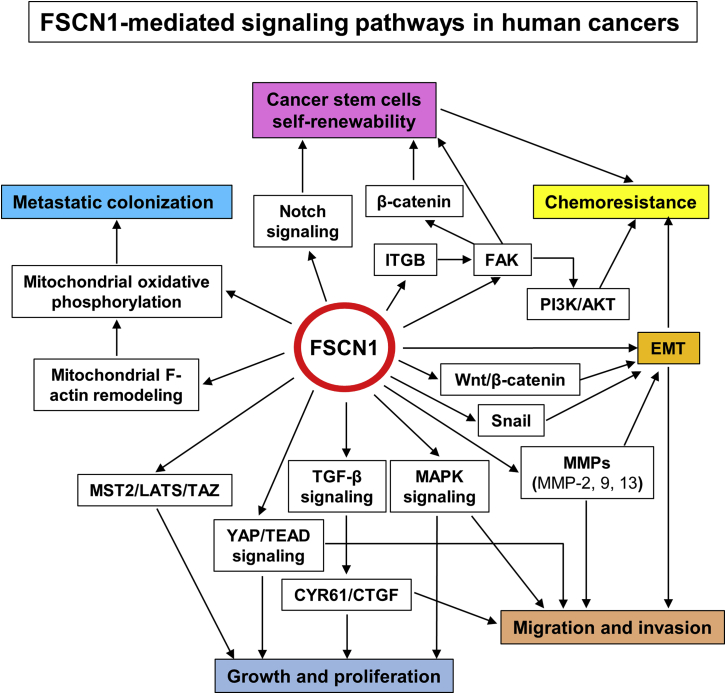

FSCN1 is highly upregulated, both at the mRNA and protein level, in various human cancer cell lines. How does this expression associate functionally with malignant properties of cancer cells? In vitro and in vivo studies have been performed in cancer cell lines using FSCN1 depletion or overexpression. Various cancer-related cellular properties, such as growth, migration, invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance, are affected by the forced changes in FSCN1 expression (summarized in Tables 1 and 2). It is not known if FSCN1 affects these features in a direct or indirect fashion. This is associated with the different types of FSCN1-mediated signaling pathways that are involved in the malignant properties of cancer cells (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the known signaling pathways mediated by FSCN1 in human cancers

Cell proliferation and tumor growth. With respect to imbalanced tumor growth, contrasting results have been reported upon in vitro manipulations of FSCN1 expression levels in cell lines. The decrease of the level of FSCN1 using synthetic siRNA or vector-based shRNA inhibits in vitro cell growth in many human cancer cell lines (Table 1). The overexpression of FSCN1 in breast (MDA-MB-435 and MDA-MB-231),73 cholangiocarcinoma (REB),123 esophageal (SHEE),88 lung (SPC-A-1, H1229),102,107 or oral (AW13516)128 cancer cell lines was found to enhance cell proliferation rates (Table 2). However, FSCN1 knockdown did not exhibit any effect on cell proliferation in multiple cancer cell lines, including bladder cancer (5637 and BIU87),70 chondrosarcoma (JJ012 and SW1353),80 hepatocellular carcinoma (HLE),100 lung cancer (H1650),65 melanoma (BLM, FM3P, and WM793),103 and oral cancer (SSC-15 and HSC-3)111 cell lines. Heterogeneous expression of FSCN1 also does not promote pancreatic cancer (MIA PaCa-2 cell line) cell proliferation.130

The contrasting roles of FSCN1 in cell proliferation have also been reported in lung cancer cell A549107,108,127 and breast cancer cell MDA-MB-23145,73,76 lines. Zhao et al.127 showed that upregulated FSCN1 exhibited a light influence on A549 non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) cell proliferation. However, Liang et al.107 found that FSCN1 enhances A549 cell proliferation by activating the YAP/TEAD signaling pathway. Moreover, Zhao et al.108 documented that FSCN1 knockdown suppresses NSCLC (A549 cells) proliferation and tumor growth through the MAPK signaling pathway. These findings were also observed in breast cancer cells. Xing et al.73 revealed that forced expression of FSCN1 promoted MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell proliferation, whereas FSCN1 knockdown inhibited MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation. Contrastingly, Al-Alwan et al.76 claimed that FSCN1 expression did not exhibit any effect on MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation. Furthermore, Heinz et al.45 also revealed that hyperexpression of FSCN1 in MDA-MB-231 cells did not exhibit any effect on cell proliferation. They hypothesized that this could be implicated in the concentration of FSCN1 protein, as there was a high basal FSCN1 level in MDA-MB-231 cells.45

In addition, injection of cancer cells, stably knocked down FSCN1 in nude mice, showed a suppressed tumor growth rate compared to control cells (Table 1). The tumor growth rate of nude mice administered with FSCN1-overexpressed cells was shown to be faster compared to the control cells of oral cancer (AW13516) and osteosarcoma (SaOS-2 and 143B).128,129 However, contrasting results have been reported. For example, Zhao et al.127 revealed that FSCN1 overexpression in A549 NSCLC cells exhibited a limited effect on tumor growth, whereas Heinz et al.45 showed that the hyperexpression of FSCN1 in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells did not exhibit any effect on tumor growth in xenograft mouse models.

Studies have reported that manipulation of FSCN1 expression in cancer cells affects tumor cell growth and proliferation. However, only a few of these studies analyzed the underlying mechanisms of action (Figure 5). For example, Xie et al.88 documented that FSCN1 regulates the proliferation of ESCC cells by modulating the expression of CTGF and CYR61 through the TGF-β signaling pathway. The MAPK and YAP/TEAD signaling pathways are involved in the FSCN1-mediated growth, migration, and invasion of NSCLC cells.107,108 Finally, Kang et al.38 demonstrated that the MST2-LATS-TAZ pathway plays an important role in FSCN1-induced melanoma tumorigenesis.

Migration, invasion, and metastasis. Downregulation of FSCN1, in a variety of cancer cell lines, not only inhibited their proliferative capacity but also their migratory and invasive abilities (Table 1). This reduction in migratory and invasive abilities was accompanied by an inhibited EMT process.79,97,101 On the contrary, the overexpression of FSCN1 was shown to promote the capacity for cell migration and invasion in many cancer cells, such as hypopharyngeal cancer cells (FaDu),126 osteosarcoma cells (SaOS-2 and 143B),129 and pancreatic cancer cells (MIA PaCa-2),116 among others (Table 2). However, in melanoma, FSCN1 knockdown did not exhibit inhibitory effects on cell migration but enhanced cell invasion.103 Studies have established an inverse relationship between FSCN1 expression and malignant or metastatic melanomas.175, 176, 177 Therefore, it is clear that FSCN1 plays a different role in melanoma compared to the other tumor types. In addition, the hyperexpression of FSCN1 was shown not to exhibit any significant effects on transmigration of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells.45 This finding is not in tandem with findings from other studies.71,73,76,122 More studies are therefore needed to understand the roles of FSCN1 in breast cancer progression.

Forced changes in FSCN1 expression were shown to alter cell metastasis in vivo. To evaluate the effects of FSCN1 on tumor spreading in a physiologically faithful microenvironment, several studies performed orthotopic transplantation of cancer cell lines into the corresponding organs of athymic nude mice.10,55,120,129 Downregulation of FSCN1 expression in prostate cancer cells DU14510 or renal cancer cells 786-O120 was shown to suppress tumor metastases in nude mice, whereas the overexpression of FSCN1 in osteosarcoma SaOS-2 cells enhanced lung metastasis in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice. The injection of cancer cells with FSCN1 knockdown into the abdominal cavities of nude mice suppressed metastatic tumor nodes when compared to those injected with control cells.95,96,115 Furthermore, FSCN1 overexpression enhances the metastasis of cancer cells.45,65,81,127,130 Upregulated FSCN1 in human tumors is functionally involved in tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis.

FSCN1 is an actin-bundling protein that cross links actin filaments to promote cell migration and invasion by forming stable filopodia and invadopodia.1,31,52 Several studies have also documented that targeted inhibition of FSCN1/actin bundling blocks tumor cell migration and metastasis.7,8,14 Moreover, Lin et al.65 reported that FSCN1 plays a role in regulating lung cancer metastatic colonization and mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation by remodeling mitochondrial actin filaments (Figure 5).

The significant functions of FSCN1 in tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis depend on its role in actin cytoskeletal reorganization and on the activities of FSCN1-mediated cell signaling pathways. EMT is a cellular process during which epithelial cells lose their epithelial characteristics and acquire a migratory and invasive mesenchymal phenotype. It is established that EMT is activated during cancer pathogenesis and is involved in enhancing migration, invasion, and metastasis.178 Evidence shows that FSCN1 is involved in the EMT process in a number of cancer types, including squamous cell carcinoma,101,111,112,153 cholangiocarcinoma,79 gastric cancer,97 and ovarian cancer.113 Varying the expression levels of FSCN1 reversed EMT in many different cancer cells, as exhibited by corresponding changes in the expression of epithelial and mesenchymal markers.79,97,101,111 Furthermore, Mao et al.79 documented that FSCN1 promotes cholangiocarcinoma cell EMT by regulating Wnt/β-catenin signaling. FSCN1 can also directly interact with and elevate snail1 levels to promote EMT in ovarian cancer cells.39 In addition, several studies have shown that FSCN1 promotes tumor cell migration and invasion by upregulating the expression of multiple matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs)101,116,126,179 (Figure 5).

Drug resistance. Chemotherapeutic drug resistance is a growing concern in cancer management. Evidence suggests that FSCN1 expression in cancer cells is involved in chemoresistance (Tables 1 and 2). Ghebeh et al.75 revealed that FSCN1 regulates chemoresistance in breast cancer. The loss of FSCN1 expression sensitized breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231) to doxorubicin therapy, whereas the expression of FSCN1 in the FSCN1-negative T47-D or SK-BR-3 breast cancer cell line conferred chemoresistance. Elevated chemoresistance levels in FSCN1-positive breast cancer cells are partially mediated through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway.75 Moreover, FSCN1 expression in breast cancer cells confers resistance to chemotherapy by regulating the self-renewal abilities of breast cancer stem cells. Chemoresistance is a key feature of cancer stem cells. Indeed, Barnawi et al.48 reported that FSCN1 is involved in the chemotherapeutic resistance of breast cancer stem cells through the activation of the Notch self-renewal signaling pathway. They also showed that FSCN1-mediated expression of ITGB1 is important in several breast cancer cell functions, such as self-renewal and chemoresistance.180 In addition, FSCN1 expression in hepatocellular carcinoma cells99 and docetaxel-resistant lung adenocarcinoma cells102 was also found to enhance to chemoresistance. In these cells, FSCN1 regulates chemoresistance through the epithelial mesenchymal transition pathway.99,102 A recent study has revealed that FSCN1 enhances paclitaxel resistance in prostate cancer. Its expression abates miR-24-3p-mediated paclitaxel sensitivity in paclitaxel-resistant prostate cancer cells.131

Cancer cell stemness. In addition to the above-mentioned cell behaviors, upregulated FSCN1 also affects cancer cell stemness. Downregulated FSCN1 in breast cancer cell lines was shown to significantly suppress the cancer stem cell-like phenotype (CD44hi/CD24lo and ALDH+).48 FSCN1 knockout in the melanoma WM793 cell line inhibited melanoma stemness. This was attributed to the fact that the expression levels of CD44 were significantly suppressed in FSCN1 knockout WM793 cells.38 Al-Alwan and coworkers48,49 documented that FSCN1 regulates breast cancer stem cell functions by activating the Notch and focal adhesion kinase (FAK)-β-catenin signaling pathway. Kang et al.38 revealed that FSCN1 increases cancer cell stemness in melanoma by inhibiting the Hippo pathway.

Is FSCN1 a cancer-driver gene?

Although FSCN1 promotes the progression of many human cancers, it is not currently listed as a cancer-driver gene. This is because the systematic sequencing of human cancer genomes has not revealed a significant rate of FSCN1 somatic gene alterations.181 To our knowledge, a single study has evaluated the effects of FSCN1 gene polymorphisms in the development and progression of breast cancer.182 The study documents that genetic variations in the FSCN1 gene may serve as a marker for early-stage breast cancer. Even though FSCN1 is not directly affected by genetic mutations, it has an important role in regulating key oncogenic pathways, such as PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, and MAPK. The available evidence is insufficient to assess the value of FSCN1 as a new driver gene in several cancer cell lines. We therefore hypothesize that FSCN1 is a downstream effector protein that is upregulated to promote migration and invasion by remodeling cytoskeletal organization in response to various oncogenic signals in tumor cells.

In conclusion, FSCN1 is highly upregulated in a variety of human cancers and functionally contributes toward cancer progression. However, contrasting results have been reported in melanoma. Due to heterogeneity in different cancer cells and the complexity of multiple molecular mechanisms underlying tumor progression, evidence regarding FSCN1 roles in cancer development and progression is fragmented and limited. Therefore, integrated studies of these molecular mechanisms in the same cancer cells are needed to elucidate on the complex physiological functions of this gene.

Is FSCN1 a promising cancer biomarker that can be used in clinical practice?

In spite of remarkable advancements in cancer research, it remains a major threat to human health. Effective cancer treatment depends on the implementation of novel therapeutic options, the development of methods for early-stage cancer diagnosis, and the assessment of an individual’s risk of cancer progression and recurrence. Cancer biomarkers in tumor tissues or serum can be used for risk evaluation, early diagnosis, tumor classification, prognosis, prediction of therapeutic responses or toxicity, and monitoring of cancer progression and recurrence.183 Therefore, effective cancer biomarkers are urgently needed to improve cancer screening, diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring. FSCN1 is a distinct 55-kDa actin-bundling protein that was identified as a sensitive marker for Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin’s disease in 1997.184 The overexpression of FSCN1 in many other human cancers and their correlation with malignant properties have elucidated the important role of FSCN1 in cancer progression and prognosis. However, studies on the clinical significance of FSCN1 in human cancers are in the initial stages.

In the last 20 years, various clinical studies have documented that FSCN1 is a novel biomarker candidate for aggressive carcinomas of many cancer types.1,3 As shown in Table 3, we summarized the potential clinical use of FSCN1 as a biomarker in different human cancers and listed the level of evidence (LOE)271,272 for its clinical use. Clinical IHC studies showed that in nearly all cancers, FSCN1 expression is associated with aggressive clinical course, metastatic progression, and poor prognosis (Table 3). Cox regression analysis revealed that FSCN1 is an independent poor prognostic marker for many different human cancers (Table S2). FSCN1 can also serve as a diagnostic marker for distinguishing triple-negative subtypes from other breast cancer types,71,203,209 thyroid carcinoma from benign lesions,267 and uterine leiomyosarcoma from leiomyoma variants.270 Even though FSCN1 is not a secreted or membrane-bound protein, serum levels of FSCN1 play a role in cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Chen et al.220 revealed that FSCN1 autoantibodies are a potential serum diagnostic biomarker for ESCC, especially early-stage ESCC. Lee et al.238 showed that serum FSCN1 could distinguish between head and neck cancer patients from healthy individuals. Two retrospective studies have documented that serum FSCN1 levels are biomarkers for aggressive progression and prognosis of NSCLC.245,246 The clinicopathological and prognostic significance of tissue and serum FSCN1 levels in different human cancers is summarized in Table S2.

Table 3.

The potential clinical applications of FSCN1 as a biomarker in human cancer

| Cancer type | Specimen | Proposed use or comments | Level of evidencea | Methods | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute myeloid leukemia | plasma | distinguishing acute myeloid leukemia from acute lymphoblastic leukemia | III | ELISA | 185 |

| Adrenocortical cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker; combined with stage or Ki67 LI, FSCN1 can refine their prognostication power | IV | IHC, WB, qRT-PCR | 186,187 |

| Ampulla of Vater adenocarcinomas | tissue | prediction of more malignant stage and poor survival | V | IHC | 188 |

| Biliary cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker | IV | IHC, qRT-PCR | 189, 190, 191, 192 |

| tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course and poor outcome | IV, V | IHC | 13,192, 193, 194 | |

| Bladder cancer | tissue | independent prediction of recurrence and survival | IV | IHC | 195,196 |

| tissue | prediction of invasion status in urothelial carcinomas | IV | IHC | 197, 198, 199 | |

| tissue | prediction of more malignant stage | IV, V | IHC | 70,200 | |

| tissue | an aid in the diagnosis of metastatic urothelial carcinoma | V | IHC | 201 | |

| tissue | does not correlate with the depth of tumor invasion or with the tumor recurrence or progression | III | IHC | 202 | |

| Breast cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker | IV | IHC | 71,203, 204, 205, 206 |

| tissue | in combination with other factors for assessing prognosis in breast cancer | IV | IHC | 204,207,208 | |

| tissue | predicting prognosis after chemotherapy | V | IHC | 75 | |

| tissue | differential diagnosis of TNBC from other cancer types | IV | IHC | 71,203,209 | |

| tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course and poor outcome | IV, V | IHC | 12,67,76,206,210 | |

| Childhood cancer | tissue | prediction of the risk of relapse | V | IHC | 211 |

| Colorectal cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker for advanced colorectal cancer | IV | IHC | 212, 213, 214, 215, 216, 217 |

| tissue | combination of FSCN1 and BMI1 as a prognostic marker | IV | IHC | 218 | |

| tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course and poor outcome | IV, V | IHC, qRT-PCR | 12,81,124,213,214,219 | |

| tissue | predicting distant metastasis | IV | IHC | 12,214,216 | |

| Esophageal cancer | serum | early detection of ESCC | V | ELISA | 220 |

| tissue | early detection of ESCC | IV | IHC | 221,222 | |

| tissue | independent poor prognostic marker | IV | IHC, qRT-PCR, WB | 87,160,223, 224, 225, 226 | |

| tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course and poor survival | IV | IHC, qRT-PCR | 12,222,224,227 | |

| Gastric cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker | IV | IHC | 228,229 |

| tissue | combined with Smad4 for predicting clinical outcomes | IV | IHC | 230 | |

| tissue | predicting lymph node or distant metastasis | IV | IHC | 12,229,231 | |

| tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course and poor outcome | IV | IHC | 12,229,231, 232, 233, 234 | |

| Gastrointestinal stromal tumor | tissue | prediction of aggressive behavior and poor outcome | IV | IHC | 163 |

| Glial tumor | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker | IV, V | IHC, qRT-PCR | 235, 236, 237 |

| Head and neck cancer | serum | differentiating cancer patients from healthy individuals | IV | ELISA | 238 |

| tissue | prediction of regional lymphatic metastasis | III, IV | IHC | 238,239 | |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course and poor outcome | IV, V | IHC | 240,241 |

| tissue | independent prognostic factor for disease-free survival | IV | IHC | 241 | |

| Laryngeal cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker | IV | IHC | 101,242,243 |

| tissue | combined with E-cadherin for predicting recurrence | V | IHC | 243 | |

| tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course | IV, V | IHC | 101,242,244 | |

| Lung cancer | serum | predicting recurrence in NSCLC | V | ELISA | 245 |

| serum | independent prognostic marker for M0-stage NSCLC; prediction of metastasis | IV | ELISA | 246 | |

| tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course | IV, V | IHC | 4,91,127,247, 248, 249, 250 | |

| tissue | independent poor prognostic marker for NSCLC patients | IV | IHC, qRT-PCR, WB | 4,91,249 | |

| Nasopharyngeal cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker; prediction of more malignant status | IV | IHC | 105 |

| Oral cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker | IV, V | IHC | 111,251,252 |

| tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course and poor outcome | IV, V | IHC | 121,128,251, 252, 253 | |

| Osteosarcoma | tissue | prediction of poor overall survival | V | IHC | 129 |

| Ovarian cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker for survival of advanced serous ovarian cancer | IV, V | IHC | 114,254 |

| tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course and poor survival | IV, V | IHC | 114,255, 256, 257, 258 | |

| Pancreatic cancer | tissue | prediction of more malignant stage and poor survival | V | IHC | 152,188,259,260 |

| Pituitary adenomas | tissue | prediction of invasion and risk of recurrence | V | IHC | 261 |

| Prostate cancer | tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course | V | IHC | 10 |

| tissue | not a suitable biomarker for prediction of aggressive prostate cancers | IV | IHC | 262 | |

| Renal cancer | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker | IV, V | IHC | 120,133 |

| tissue | prediction of more malignant stage and poor survival | IV, V | IHC | 263,264 | |

| Small intestinal carcinoma | tissue | independent poor prognostic marker; prediction of lymph node metastasis | IV | IHC | 265 |

| Soft tissue sarcomas | tissue | prediction of disease-specific survival | V | IHC | 266 |

| Thyroid cancer | tissue | distinguishing thyroid carcinoma from benign lesions | IV | IHC | 267 |

| Uterine cancer | tissue | prediction of more aggressive clinical course and poor outcome | V | IHC | 268,269 |

| tissue | differentiating uterine leiomyosarcoma from leiomyoma variants | V | IHC | 270 |

IHC, immunohistochemistry of conventional tissue sections; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; qRT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction; WB, western blot; TNBC, triple-negative breast cancer.

Level of evidence:271 level I, evidence from a single, high-powered, prospective, controlled study that is specifically designed to test the marker or evidence from a meta-analysis, pooled analysis, or overview of level II or III studies; level II, evidence from a study in which marker data are determined in relationship to a prospective therapeutic trial that is performed to test a therapeutic hypothesis but not specifically designed to test marker utility; level III, evidence from large prospective studies; level IV, evidence from small retrospective studies; level V, evidence from small pilot studies.

The LOE reflects the strength of current evidence for clinical utility of a biomarker. According to the criteria for LOE, as defined by Hayes et al.,271 LOE I represents the highest evidence, whereas LOE V represents the poorest evidence for the clinical utility of a particular biomarker. Although FSCN1 is a promising biomarker candidate for aggressive carcinomas, its current LOE is low (level IV or V; Table 3). To our knowledge, only three prospective studies have a higher LOE (level III).202,219,239 There are several explanations for this low LOE. Many studies were piloted to determine FSCN1 expression in sample populations or to correlate FSCN1 levels with clinicopathological parameters. These studies were not designed to determine the clinical utility of FSCN1; therefore, their LOE was level V. Moreover, most of these studies were designed retrospectively, thereby providing a low LOE (level IV) when compared to prospectively designed studies (level III). Several systematic reviews and meta-analyses have established that FSCN1 is a potential biomarker for the identification of aggressive metastatic tumors or prognosis.5,12,13,189,223,232 However, the evidence from these retrospectively reviews cannot be considered as higher LOE. To improve the LOE, studies should preferably select appropriate samples from previously established prospective cohorts.

Since the current LOE for clinical utility of FSCN1 is low, it raises an important question: how far are we from using FSCN1 as a cancer biomarker in clinical practice? Several studies have discussed the process of biomarker development (e.g., Pepe et al.,273 Rifai et al.,274 and Pavlou et al.275). A simplistic version of a biomarker development pipeline275 includes 4 sequential phases: phase 1, preclinical exploratory studies; phase 2, clinical assay development; phase 3, retrospective validation studies; and phase 4, prospective validation studies. Various challenges at different levels must be overcome before a biomarker moves from one phase to the other. Only biomarkers that successfully reach phase 4 are approved for clinical use.273, 274, 275

The expression of FSCN1 is associated with an aggressive clinical course and poor outcomes in different cancer types (Tables 3 and S2). Therefore, FSCN1 seems a promising cancer biomarker. However, in (nearly) all cancer types, FSCN1 does not progress beyond phase 2 of the biomarker development pipeline.275 This has been attributed to the lack of retrospective validation studies. In contrast to the retrospective studies in phase 1 or 2, retrospective validation studies (phase 3) require bigger sample sizes that reflect the biological variability of the targeted population to ensure a rigorous statistical analysis. The vast majority of published studies was retrospectively designed to investigate the associations between FSCN1 levels with clinicopathological parameters or outcomes of interest. The aim of these studies was to explore or evaluate the potential of FSCN1 as a biomarker (e.g., the studies in gastric228,229 and liver240,241 cancer). In addition, FSCN1, as an independent poor prognostic marker for aggressiveness, has been evaluated in multiple patient populations of some cancers (e.g., breast, colon, and esophageal cancer). However, the available evidence is insufficient for assessing the independent value of fascin-1 as a new biomarker. This is because individual studies are not always consistent.12 Furthermore, only a few relevant studies have been performed to investigate the potential of FSCN1 as a biomarker in certain types of human cancer (Table 3). Apart from breast cancer,12 inconsistent results were also found in several other cancer types, such as bladder195,196,202 and prostate10,262 cancer. Therefore, prospective studies with bigger sample sizes are also needed to fully determine the predictive or prognostic value of FSCN1.

Several reasons have been postulated as to why FSCN1 has not been approved as a biomarker in clinical practice.3,5,6,12 First, there is a lack of sufficient evidence to assess the independent value of FSCN1 as a new biomarker.5,12 Contrasting findings between individual studies are not conclusive as to whether FSCN1 is a reliable biomarker, therefore. Contrasting results inhibit large-scale and well-designed prospective studies. Second, because FSCN1 is not a secreted or membrane-bound protein, it cannot be used as a serum biomarker for different cancer types. Third, previous studies have shown that FSCN1 is highly expressed in many different cancer types (Table S1); therefore, it is not specific to any tumor tissue type to be a good biomarker. More studies should be done to determine the clinical relevance and applicability of FSCN1 in the most relevant cancers.

Therapeutic potential of FSCN1

Evidence shows that FSCN1 is a viable novel target molecule for anti-cancer or anti-metastatic therapy in multiple human cancers.1,5,7,10,12,121 As a therapeutic target, FSCN1 has several advantages: (1) it is important for tumor progression and promotes tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis (refer to Tables 1 and 2); (2) it is upregulated in many human cancers and has been correlated with clinically aggressive phenotypes and poor prognosis (refer to Table 3); and (3) FSCN1 knockout mice are viable,61,276 suggesting that targeting FSCN1 would have limited side effects in patients. Currently, siRNA, shRNA, miRNAs, small molecule inhibitors, and nanobodies have been experimentally used for targeting FSCN1.

siRNA can be used for specific degradation of targeted mRNA and therefore, reducing protein abundance. This enhances the utilization of siRNA as a powerful tool to study the functions of a specific gene. In most of the tumor cell lines (Table 1), FSCN1 knockdown by siRNA inhibited cell migration and invasion in vitro. Several studies of multiple cancer types have also shown that the downregulation of FSCN1 through siRNA or shRNA is effective at suppressing tumor cell metastasis in vivo.10,55,65,95,96,115,120 These studies suggest that using siRNA to downregulate FSCN1 expression in tumors may be a new class of therapeutics for metastatic cancers. However, the clinical feasibility of using siRNA as a therapeutic option is hampered by its off-target effects.

In addition, studies performed in multiple cancer cell lines indicate that overexpression of miRNAs, such as miR-145, inhibits cell growth, cell migration, and invasion by directly targeting FSCN1.82,101,117 However, the clinical applications of miRNAs or miRNA-based reagents as therapeutic options have significant limitations.277

Small molecule inhibitors of FSCN1 can block tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis.7,8,14,15,278 Moreover, this category of inhibitors could potentially be useful against FSCN1-positive tumors from different tissues. In the last 10 years, FSCN1 has been identified as a protein target for a number of small molecule compounds. In 2010, Huang and coworkers7 showed that migrastatin analogs can block tumor metastasis by targeting FSCN1 to inhibit its activity. Small molecule compound G2 and its improved analogs have also been shown to inhibit the actin-binding activity of FSCN1, tumor cell migration and invasion, and metastasis in mouse models.8,14,15 Alburquerque-González et al.278 demonstrated that the anti-depressant imipramine inhibits FSCN1 and plays a role in inhibiting the migration and invasion of colorectal cancer cells. A series of thiazole derivatives,32,33 isoquinolone and pyrazolo[4,3-c] pyridine,34 have also been shown to be inhibitors of FSCN1. However, these small molecule compounds provide promising start points for the development of FSCN1-targeted anti-metastatic therapies.

Another approach that targets the FSCN1 protein is the use of an inhibitory nanobody that disrupts FSCN1/actin bundling.279 When expressed inside prostate cancer cells (PC3) or breast cancer cells (MDA-MB-231), FSCN1-specific nanobodies inhibited invadopodium formation and cell invasion.279 However, it has not been established whether this FSCN1-specific nanobody can be developed for clinical applications.

The possible utilization of FSCN1 as a therapeutic target is inhibited by multiple limitations. Studies are aimed at developing novel agents that can interfere with key FSCN1 functions in cancers.8,33,278, 279, 280 It is foreseeable that creative agents (siRNAs, small molecule inhibitors, nanobody, etc.) will be developed to specifically inhibit FSCN1-mediated tumor metastasis. However, FSCN1 expression can promote cell migration and metastasis independent of its actin-bundling activity.36,44,45,63 This should be taken into consideration when developing therapeutic options that inhibit FSCN1/actin-bundling activity.

Conclusions

Studies have shown that FSCN1 is expressed in many human cancer types. Its expression has been correlated with aggressive clinical course and poor prognosis.1,9,11,12,281 In vitro manipulation of FSCN1 expression in tumor cell lines has shown that FSCN1 promotes tumor cell growth, migration, invasion, and metastasis (Tables 1 and 2). Furthermore, FSCN1 is involved in the regulation of key oncogenic pathways, such as EMT, PI3K/AKT, Wnt/β-catenin, MAPK, among others (Figure 5). Therefore, FSCN1 is a potential biomarker for aggressive, metastatic cancers6,9,12 and is a therapeutic target for blocking tumor cell migration, invasion, and metastasis.3,7,8,10,14,282 However, it has not been established whether FSCN1 can be developed as a novel biomarker or therapeutic target. More studies are needed to determine whether FSCN1 has value as a biomarker in the most relevant cancers, over biomarkers that are in current clinical use, and whether targeting FSCN1 with small molecules will be useful for cancer therapy.

In addition, due to heterogeneity in different cancer cells and the complexity of multiple molecular mechanisms underlying tumor progression, evidence regarding FSCN1 roles in cancer development and progression is fragmented and limited. Therefore, much remains to be learned about the role of FSCN1 in human cancers. For example, FSCN1 is important for cancer cell stemness,38,48,49 extracellular vesicle release,47 chemoresistance,75 and anoikis resistance,283 yet the mechanisms involved are largely unclear. Investigation of the relationship among mitochondrial metabolism, FSCN1, and metastatic colonization in cancers has begun;65 more widespread investigations can be expected in the next few years. Although FSCN1 overexpression has been extensively reported in different human cancers, molecular mechanisms underlying FSCN1 upregulation during malignant transformation and metastatic progression are under-studied areas. It is also unknown whether super enhancers, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification, or RNA binding proteins play a role in the regulation of FSCN1 expression. Understanding these roles and mechanistic regulation of FSCN1 in cancers will be crucial for the development of therapeutic interventions targeting FSCN1.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81802793 and 82073101); Natural Science Foundation of Shanxi Province (201801D221419); a research project of Shanxi Province Health and Family Planning Commission (2018036); Youth Foundation of First Hospital Affiliated with Shanxi Medical University (YQ161701); a science research start-up fund for Doctor of Shanxi Province (SD1803); a science research start-up fund for Doctor of Shanxi Medical University (XD1801); Scientific and Technological Innovation Programs of Higher Education Institutions in Shanxi (STIP; 201804024); an open fund from Key Laboratory of Cellular Physiology (Shanxi Medical University); a research project supported by Shanxi Scholarship Council of China (number 2020165); an open fund from Key Laboratory of Cellular Physiology affiliated with China’s Ministry of Education in Shanxi Medical University (KLMEC/SXMU-202008 and -202009); and a fund of Shanxi “1331 Project” Key Subjects Construction (1331KSC).

Author contributions

W.G. and Y.W. conceived this manuscript. H.L., Y.Z., and L.L. collected and prepared the related references, drafted the manuscript, and performed data analysis and tabulation. Y.G., H.L., and J.C. drew the figures. W.G., Y.W., and J.C. supervised and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omto.2020.12.014.

Contributor Information

Yongyan Wu, Email: wuyongyan@sxent.org.

Wei Gao, Email: gaoweisxent@sxent.org.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Hashimoto Y., Kim D.J., Adams J.C. The roles of fascins in health and disease. J. Pathol. 2011;224:289–300. doi: 10.1002/path.2894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams J.C. Roles of fascin in cell adhesion and motility. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2004;16:590–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashimoto Y., Skacel M., Adams J.C. Roles of fascin in human carcinoma motility and signaling: prospects for a novel biomarker? Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:1787–1804. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelosi G., Pastorino U., Pasini F., Maissoneuve P., Fraggetta F., Iannucci A., Sonzogni A., De Manzoni G., Terzi A., Durante E. Independent prognostic value of fascin immunoreactivity in stage I nonsmall cell lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2003;88:537–547. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams J.C. Fascin-1 as a biomarker and prospective therapeutic target in colorectal cancer. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2015;15:41–48. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.976557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kulasingam V., Diamandis E.P. Fascin-1 is a novel biomarker of aggressiveness in some carcinomas. BMC Med. 2013;11:53. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L., Yang S., Jakoncic J., Zhang J.J., Huang X.Y. Migrastatin analogues target fascin to block tumour metastasis. Nature. 2010;464:1062–1066. doi: 10.1038/nature08978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang F.K., Han S., Xing B., Huang J., Liu B., Bordeleau F., Reinhart-King C.A., Zhang J.J., Huang X.Y. Targeted inhibition of fascin function blocks tumour invasion and metastatic colonization. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7465. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma Y., Machesky L.M. Fascin1 in carcinomas: Its regulation and prognostic value. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;137:2534–2544. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Darnel A.D., Behmoaram E., Vollmer R.T., Corcos J., Bijian K., Sircar K., Su J., Jiao J., Alaoui-Jamali M.A., Bismar T.A. Fascin regulates prostate cancer cell invasion and is associated with metastasis and biochemical failure in prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2009;15:1376–1383. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machesky L.M., Li A. Fascin: Invasive filopodia promoting metastasis. Commun. Integr. Biol. 2010;3:263–270. doi: 10.4161/cib.3.3.11556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan V.Y., Lewis S.J., Adams J.C., Martin R.M. Association of fascin-1 with mortality, disease progression and metastasis in carcinomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2013;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruys A.T., Groot Koerkamp B., Wiggers J.K., Klümpen H.J., ten Kate F.J., van Gulik T.M. Prognostic biomarkers in patients with resected cholangiocarcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2014;21:487–500. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han S., Huang J., Liu B., Xing B., Bordeleau F., Reinhart-King C.A., Li W., Zhang J.J., Huang X.Y. Improving fascin inhibitors to block tumor cell migration and metastasis. Mol. Oncol. 2016;10:966–980. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montoro-García S., Alburquerque-González B., Bernabé-García Á., Bernabé-García M., Rodrigues P.C., den-Haan H., Luque I., Nicolás F.J., Pérez-Sánchez H., Cayuela M.L. Novel anti-invasive properties of a Fascin1 inhibitor on colorectal cancer cells. J. Mol. Med. (Berl.) 2020;98:383–394. doi: 10.1007/s00109-020-01877-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sedeh R.S., Fedorov A.A., Fedorov E.V., Ono S., Matsumura F., Almo S.C., Bathe M. Structure, evolutionary conservation, and conformational dynamics of Homo sapiens fascin-1, an F-actin crosslinking protein. J. Mol. Biol. 2010;400:589–604. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.04.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang S., Huang F.K., Huang J., Chen S., Jakoncic J., Leo-Macias A., Diaz-Avalos R., Chen L., Zhang J.J., Huang X.Y. Molecular mechanism of fascin function in filopodial formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:274–284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.427971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jansen S., Collins A., Yang C., Rebowski G., Svitkina T., Dominguez R. Mechanism of actin filament bundling by fascin. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:30087–30096. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.251439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anilkumar N., Parsons M., Monk R., Ng T., Adams J.C. Interaction of fascin and protein kinase Calpha: a novel intersection in cell adhesion and motility. EMBO J. 2003;22:5390–5402. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zanet J., Jayo A., Plaza S., Millard T., Parsons M., Stramer B. Fascin promotes filopodia formation independent of its role in actin bundling. J. Cell Biol. 2012;197:477–486. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201110135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aramaki S., Mayanagi K., Jin M., Aoyama K., Yasunaga T. Filopodia formation by crosslinking of F-actin with fascin in two different binding manners. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2016;73:365–374. doi: 10.1002/cm.21309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ono S., Yamakita Y., Yamashiro S., Matsudaira P.T., Gnarra J.R., Obinata T., Matsumura F. Identification of an actin binding region and a protein kinase C phosphorylation site on human fascin. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:2527–2533. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]