Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)-associated pruritus, generalized itching related to CKD, affects many aspects of hemodialysis patients’ lives. However, information regarding the relationship between pruritus and several key outcomes in hemodialysis patients remains limited.

Study Design

Prospective cohort.

Setting & Participants

23,264 hemodialysis patients from 21 countries in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) phases 4 to 6 (2009-2018).

Exposure

Pruritus severity, based on self-reported degree to which patients were bothered by itchy skin (5-category ordinal scale from “not at all” to “extremely”).

Outcomes

Clinical, dialysis-related, and patient-reported outcomes.

Analytical Approach

Cox regression for time-to-event outcomes and modified Poisson regression for binary outcomes, adjusted for potential confounders.

Results

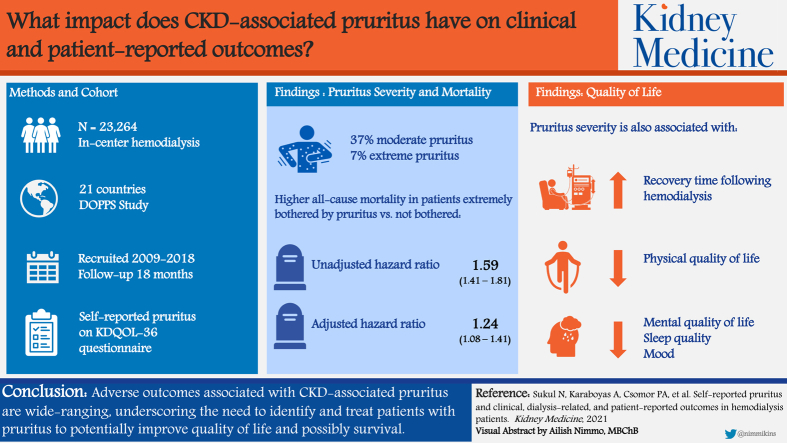

The proportion of patients at least moderately bothered by pruritus was 37%, and 7% were extremely bothered. Compared with the reference group (“not at all”), the adjusted mortality HR for patients extremely bothered by pruritus was 1.24 (95% CI, 1.08-1.41). Rates of cardiovascular and infection-related deaths and hospitalizations were also higher for patients extremely versus not at all bothered by pruritus (HR range, 1.17-1.44). Patients extremely bothered by pruritus were also more likely to withdraw from dialysis and miss hemodialysis sessions and were less likely to be employed. Strong monotonic associations were observed between pruritus severity and longer recovery time from a hemodialysis session, lower physical and mental quality of life, increased depressive symptoms, and poorer sleep quality.

Limitations

Residual confounding, recall bias, nonresponse bias.

Conclusions

Our findings demonstrate how diverse and far-reaching poor outcomes are for patients who experience CKD-associated pruritus, specifically those with more severe pruritus. There is need for change in practice patterns internationally to effectively identify and treat patients with pruritus to reduce symptom burden and improve quality of life and possibly even survival.

Index Words: pruritus, patient-reported outcomes, hemodialysis, quality of life

Graphical abstract

Plain-Language Summary.

Chronic kidney disease–associated pruritus (itch) significantly affects many hemodialysis patients but much is still unknown. We analyzed associations between itch severity and several key outcomes in a large international sample of hemodialysis patients between 2009 and 2018. Itching was associated with higher risk for mortality, while patients extremely bothered by itching were more likely to withdraw from dialysis and miss hemodialysis sessions and less likely to be employed compared with those not bothered. We showed strong associations between increasing itch severity and longer recovery time from a hemodialysis session, lower physical and mental quality of life, increased depressive symptoms, and poorer sleep quality. There is a clear need for change in practice patterns to reduce the symptom burden of itch and improve quality of life.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD)-associated pruritus, generalized itching related to CKD, affects many patients with advanced CKD1,2 and patients with end-stage kidney disease receiving dialysis.3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 In 2006, a large international study of hemodialysis (HD) patients participating in the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) showed that 45% and 42% of patients receiving HD from 1996 to 1999 and from 2000 to 2003, respectively, experienced moderate to extreme pruritus,3 though studies have shown that pruritus in general can affect up to 87% of patients receiving dialysis.10 Based on more recent DOPPS data, Rayner et al4 have shown that the prevalence of moderate to extreme pruritus remained high at 37% in 2012 to 2015, ranging from 26% in Germany to 48% in the United Kingdom.

Prior studies have demonstrated that CKD-associated pruritus causes distress in HD patients that ranges from sporadic discomfort to complete restlessness11; contributes to restless sleep, agitation, and depression4; and has been associated with increased mortality.3,12,13 These studies underscore the importance of better defining the presence of pruritus and its impact on the lives of HD patients. In addition to these outcomes, studies have also demonstrated an association between pruritus and worse kidney disease burden scores, as well as poorer health-related quality of life (HR-QoL).3,8,14, 15, 16 The pathophysiology of pruritus remains unclear.11,17, 18, 19

In addition to skin emollients, hydrating creams, and UV light therapy, proposed medications have included antihistamines, gabapentin, pregabalin, and nalfurafine,18,20, 21, 22, 23, 24 but there are limitations to these studies and pruritus often remains inadequately treated, although research on emerging therapies is ongoing.25

Data are lacking on how pruritus affects other clinical, dialysis-related, and patient-reported outcomes (PROs). In this study, we used a large contemporary international sample of patients receiving HD to describe the prevalence of pruritus by patient-reported severity and by country and to investigate associations of pruritus severity with mortality, hospitalizations, and clinical outcomes including withdrawal from dialysis, missed dialysis treatments, recovery time from a dialysis session, HR-QoL, and employment status.

Methods

Data Source

The DOPPS is an international prospective cohort study of patients 18 years or older treated with in-center HD in 21 countries. Maintenance HD patients were randomly selected from national samples of HD facilities in each country; detailed information is included in prior publications26,27 and at http://www.dopps.org. Study approval and patient consent were obtained as required by national and local ethics committee regulations. This analysis included data from DOPPS phase 4 (2009-2011), phase 5 (2012-2015), and phase 6 (2015-2018) in all DOPPS countries with available data.

Variables

Our exposure variable was patient response to a single question (of 12) included in the Symptoms and Problems subscale of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life 36-item short form survey (KDQOL-36)28 component of the self-administered patient questionnaire: During the past 4 weeks, to what extent were you bothered by itchy skin? Response options were not at all, somewhat, moderately, very much, and extremely.

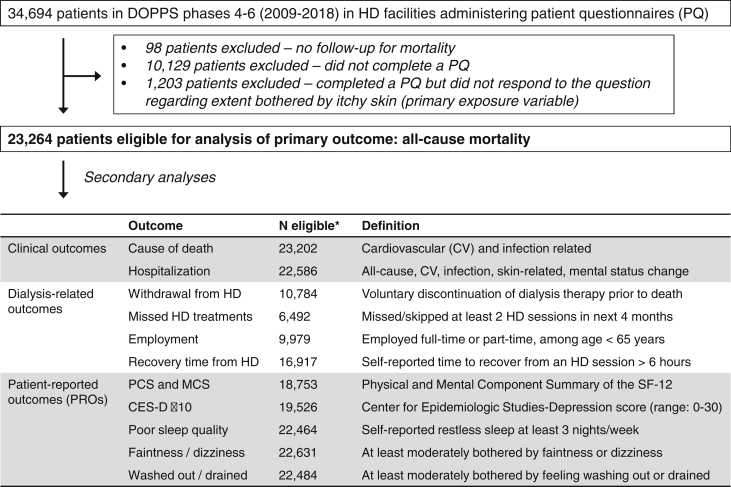

Several outcomes were investigated and are summarized in Figure 1. Outcomes were grouped into 3 categories: clinical outcomes, dialysis-related outcomes, and PROs.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of inclusion/exclusion criteria for primary analysis and list of secondary outcomes. ∗Number of eligible patients for each secondary analysis varies based on data availability of each outcome variable, as detailed in Methods. Abbreviations: CES-D, Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression; DOPPS, Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study; HD, hemodialysis; MCS, Mental Component Summary; PCS, Physical Component Summary; SF-12, 12-Item Short Form Health Survey.

The primary clinical outcome was time to all-cause mortality. Other clinical outcomes included cardiovascular (CV) and infection-related death, all-cause and cause-specific hospitalizations including CV, infection, skin-related (ie, cellulitis/skin infection, rash, or other unspecified skin-related diagnosis), and “mental status change/confusion” admissions. HD facilities not reporting hospitalizations or cause of death were excluded from these analyses. A listing of causes of death and hospitalization diagnosis/procedure codes is presented in Table S1.

Dialysis-related outcomes included withdrawal from dialysis, missed/skipped HD treatments, employment, and recovery time from an HD session. Patients were considered to have withdrawn from dialysis if their cause of death or reason cited for leaving DOPPS was listed as “withdrawal from dialysis.” All patients who withdrew from dialysis died following their withdrawal. Countries with withdrawal rates < 0.01 (China, the Gulf Cooperation Council countries [Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates], Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, and Turkey) were not included in this analysis. The number of missed treatments in each of the past 4 months was abstracted from medical records; patients were considered to have missed or skipped treatments if they missed at least 2 treatments during the past 4 months. Countries with missed treatment rates <0.01 (Italy, Japan, and Turkey) were not included in this analysis; further, missed treatments were only captured in DOPPS phases 5 and 6 (not phase 4). Employment status was abstracted from medical records and was defined as full- or part-time employment, restricted to patients younger than 65 years. Self-reported recovery time from an HD session was assessed on the patient questionnaire by the question, “How long does it take you to recover from a dialysis session?”29 Response options were less than 2, 2 to 6, 7 to 12, and more than 12 hours, and we dichotomized the outcome at 6 hours.

PROs included measures of HR-QoL, depression, sleep quality, faintness/dizziness, and feeling washed out/drained. Mental (MCS) and Physical Component Summary (PCS) scores (higher = better HR-QoL) were derived from the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey, a subset of the KDQOL-36.28 The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) score was derived from the 10-item CES-D Boston form while maintaining the 4 response categories used in the 20-item CES-D Yale form for greater precision; a score ≥ 10 on the 30-point scale is indicative of depressive symptoms.30 Sleep quality was assessed on the patient questionnaire by the CES-D question, “During the past week, how often did you feel your sleep was restless?” Response options were: 0, 1 to 2, 3 to 4, and 5 to 7 nights per week, and we considered 3+ nights as poor sleep quality. Faintness/dizziness and feeling washed out/drained were each assessed by a single question from the KDQOL-3628 asking about the extent of bother from each of these factors during the past 4 weeks; response options were the same as for the itchy skin question, and we defined the outcome as at least moderately bothered.

Information on patient demographics and comorbid condition history was abstracted from medical records at DOPPS enrollment in each study phase. Laboratory measures and catheter use were updated monthly and selected based on closest proximity to the completed patient questionnaire.

Statistical Analysis

We first described patient characteristics of the study population and compared included versus excluded patients to assess how patient questionnaire nonresponders may differ from responders. We also compared patient characteristics by degree of self-reported pruritus. The distribution of the exposure variable was summarized overall and by DOPPS country.

Associations between pruritus and time-to-event outcomes (clinical outcomes + withdrawal from dialysis) were assessed using Cox regression models, stratified by DOPPS phase and country, and using a robust sandwich covariance estimator to account for facility clustering. Time at risk began at the time of patient questionnaire completion and ended at the time of the event of interest, 7 days after leaving the facility due to transfer or change in modality, loss to follow-up, or administrative end of study phase (whichever occurred first). Proportional hazards assumptions were checked by examination of log-log survival plots. Because odds ratios will not approximate risk ratios when the outcome is not rare, we instead presented prevalence ratios to estimate the associations between pruritus and binary outcomes (≥2 missed treatments, employment, recovery time > 6 hours, CES-D score ≥ 10, poor sleep quality, faintness/dizziness, and washed out/drained). Because a log-binomial regression approach failed to converge, a problem frequently encountered,31 we used a modified Poisson regression approach, a valid alternative when log-binomial regression fails to converge.32 Associations between pruritus and normally distributed outcomes (PCS and MCS scores) were assessed using linear mixed models with a random facility intercept to account for clustering.

All models accounted for facility clustering using robust variance estimators and were adjusted for the following potential confounders: DOPPS phase and country, age, sex, vintage, body weight (postdialysis), catheter use, 15 summary comorbid conditions (listed in Table 1), serum albumin level, hemoglobin level, and serum phosphorus level.

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Degree of Self-reported Pruritus

| Patient Characteristic | N | Self-reported Extent Bothered by Itchy Skin |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at All | Somewhat | Moderately | Very Much | Extremely | ||

| No. of patients | 23,264 | 7,665 (33%) | 7,009 (30%) | 4,258 (18%) | 2,711 (12%) | 1,621 (7%) |

| Case-mix | ||||||

| Age, y | 23,207 | 63.6 ± 14.7 | 63.2 ± 14.4 | 64.5 ± 14.4 | 64.7 ± 14.4 | 64.7 ± 14.4 |

| Male sex | 23,248 | 4,647 (61%) | 4,322 (62%) | 2,679 (63%) | 1,681 (62%) | 992 (61%) |

| Vintage, y | 23,05 | 2.5 [0.7-6.1] | 2.8 [0.9-6.4] | 2.7 [0.8-6.2] | 2.6 [0.7-6.0] | 2.5 [0.8-6.0] |

| Postdialysis weight, kg | 22,794 | 71 ± 19 | 69 ± 19 | 70 ± 20 | 70 ± 19 | 69 ± 20 |

| Treatments | ||||||

| IDWL, % of body weight | 22,769 | 2.8 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | 3.0 ± 1.4 | 3.1 ± 1.4 | 3.2 ± 1.4 |

| Single pool Kt/V | 18,777 | 1.51 ± 0.32 | 1.47 ± 0.32 | 1.48 ± 0.33 | 1.47 ± 0.33 | 1.45 ± 0.32 |

| <3 HD sessions/wk | 23,067 | 301 (4%) | 320 (5%) | 204 (5%) | 102 (4%) | 60 (4%) |

| Catheter use | 21,150 | 1,488 (21%) | 1,099 (17%) | 840 (22%) | 500 (20%) | 352 (24%) |

| Hemodiafiltration | 23,048 | 1,356 (18%) | 1,062 (15%) | 677 (16%) | 411 (15%) | 247 (15%) |

| ESA use | 22,499 | 6,324 (85%) | 5,836 (86%) | 3,510 (85%) | 2,257 (86%) | 1,355 (87%) |

| ESA dose, 1,000 U/wk) | 18,029 | 7.0 [4.0-12.0] | 7.4 [4.0-11.5] | 7.5 [4.5-12.0] | 7.5 [4.5-12.0] | 8.0 [5.0-12.5] |

| Laboratory values | ||||||

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 22,768 | 11.2 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ± 1.4 | 11.1 ± 1.4 | 11.0 ± 1.5 | 10.9 ± 1.5 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL | 21,844 | 3.72 ± 0.48 | 3.73 ± 0.46 | 3.68 ± 0.48 | 3.66 ± 0.48 | 3.60 ± 0.50 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dL | 22,562 | 8.4 ± 2.9 | 9.1 ± 3.0 | 8.7 ± 3.0 | 8.6 ± 3.1 | 8.6 ± 2.9 |

| C-Reactive protein, mg/L | 12,335 | 4.0 [1.3-10.0] | 3.0 [1.0-8.0] | 4.0 [1.2-10.0] | 4.0 [1.0-10.5] | 4.8 [1.4-12.2] |

| Serum phosphorus, mg/dL | 22,606 | 5.1 ± 1.5 | 5.2 ± 1.6 | 5.2 ± 1.6 | 5.3 ± 1.7 | 5.4 ± 1.7 |

| Parathyroid hormone, pg/mL | 20,241 | 218 [114-387] | 209 [110-382] | 219 [111-399] | 222 [109-399] | 209 [103-401] |

| Serum calcium, mg/dL | 22,006 | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 8.9 ± 0.8 | 8.9 ± 0.8 |

| Comorbid conditions | ||||||

| Coronary artery disease | 23,119 | 2,496 (33%) | 2,140 (31%) | 1,444 (34%) | 989 (37%) | 584 (36%) |

| Heart failure | 23,080 | 1,410 (19%) | 1,308 (19%) | 856 (20%) | 655 (24%) | 392 (24%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 23,113 | 1,073 (14%) | 901 (13%) | 580 (14%) | 414 (15%) | 284 (18%) |

| Other cardiovascular disease | 23,128 | 1,976 (26%) | 1,765 (25%) | 1,115 (26%) | 789 (29%) | 460 (29%) |

| Cancer (non-skin) | 23,051 | 1,104 (15%) | 897 (13%) | 543 (13%) | 365 (14%) | 208 (13%) |

| Diabetes | 23,065 | 2,932 (39%) | 2,727 (39%) | 1,795 (43%) | 1,171 (44%) | 722 (45%) |

| Gastrointestinal bleeding | 22,992 | 276 (4%) | 243 (4%) | 175 (4%) | 153 (6%) | 65 (4%) |

| Hypertension | 23,040 | 6,543 (86%) | 5,954 (86%) | 3,608 (86%) | 2,324 (86%) | 1,379 (86%) |

| Lung disease | 23,103 | 810 (11%) | 638 (9%) | 525 (12%) | 346 (13%) | 209 (13%) |

| Neurologic disease | 23,134 | 644 (8%) | 526 (8%) | 348 (8%) | 236 (9%) | 154 (10%) |

| Dementia | 22,776 | 61 (1%) | 51 (1%) | 45 (1%) | 21 (1%) | 22 (1%) |

| Non-dementia | 23,134 | 583 (8%) | 475 (7%) | 303 (7%) | 215 (8%) | 132 (8%) |

| Psychiatric disorder | 23,116 | 961 (13%) | 812 (12%) | 589 (14%) | 409 (15%) | 264 (16%) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 23,120 | 1,746 (23%) | 1,420 (20%) | 977 (23%) | 689 (26%) | 412 (26%) |

| Recurrent cellulitis, gangrene | 23,092 | 544 (7%) | 447 (6%) | 300 (7%) | 233 (9%) | 142 (9%) |

| Hepatitis C | 22,960 | 315 (4%) | 373 (5%) | 229 (5%) | 149 (6%) | 108 (7%) |

| Cirrhosis | 23,039 | 96 (1%) | 88 (1%) | 69 (2%) | 65 (2%) | 39 (2%) |

Note: Values expressed as mean ± standard deviation, median [interquartile range], or number (percent). ESA dose shown among ESA users. IDWL expressed in terms of percent body weight. Neurologic disease includes dementia, seizure disorder, cognitive impairment, and Parkinson disease. Psychiatric disorder includes depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia/psychotic disorder, alcohol abuse within past 12 months, and other substance abuse within past 12 months.

Abbreviations: ESA, erythropoiesis-stimulating agent; HD, hemodialysis; IDWL, intradialytic weight loss.

We used multiple imputation, assuming data were missing at random, to impute missing covariate values using the sequential regression multiple imputation method by IVEware (Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan).33 Results from 20 such imputed data sets were combined for the final analysis using Rubin’s formula.34 The proportion of missing data was <5% for all covariates, with the exception of vascular access (9%) and serum albumin level (6%). All analyses were conducted using SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Results

Study Sample

This analysis included 23,264 HD patients who responded to a survey question asking about the extent the patient was bothered by itchy skin during the past 4 weeks. We excluded 11,430 patients for various reasons, mostly due to survey nonresponse (Fig 1). Included patients tended to be healthier, for example, fewer comorbid conditions and better nutritional/inflammatory markers (Table S2).

Descriptive Data

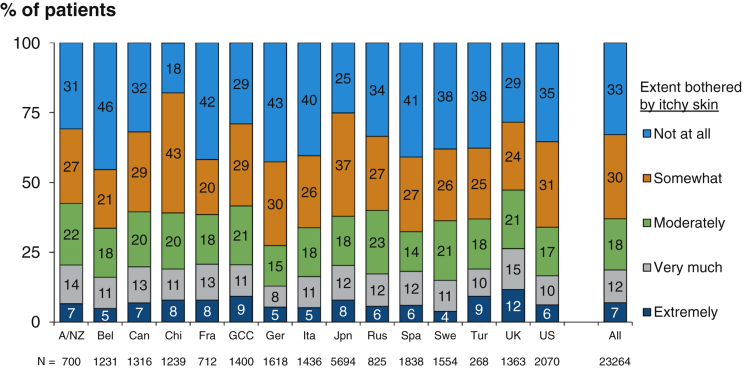

The proportions of patients not at all, somewhat, moderately, very much, and extremely bothered by pruritus were 33%, 30%, 18%, 12%, and 7%, respectively. The proportion of those who were at least moderately bothered by pruritus was highest in the United Kingdom (47%) and lowest in Germany (27%; Fig 2). The prevalence of moderate to extreme pruritus among all participants was 37%. Overall, prevalence was unchanged across DOPPS phases, though there was some variation by country (Fig S1). Patient characteristics by pruritus severity are summarized in Table 1; patients more bothered by itchy skin tended to be slightly older with greater comorbidity, be more likely to dialyze with a catheter, and had higher serum phosphorus levels and lower hemoglobin and serum albumin levels.

Figure 2.

Self-reported pruritus, by country. Abbreviations: A/NZ, Australia/New Zealand; Bel, Belgium; Can, Canada; Chi, China; Fra, France; GCC, Gulf Cooperation Council countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates); Ger, Germany; Ita, Italy; Jpn, Japan; Rus, Russia; Spa, Spain; Swe, Sweden; Tur, Turkey; UK, United Kingdom; US, United States.

Pruritus and Clinical Outcomes

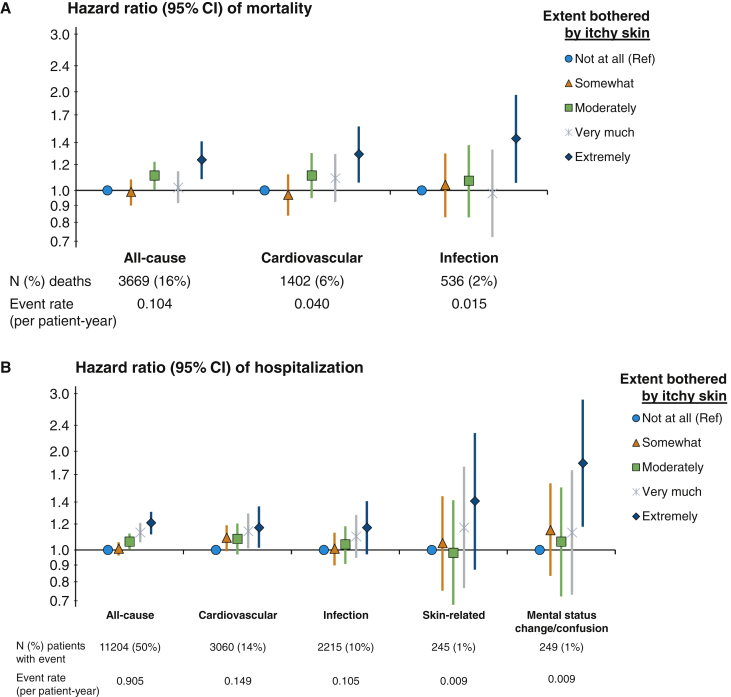

The adjusted associations between self-reported pruritus and clinical outcomes are illustrated in Figure 3. Median follow-up time was 18 (interquartile range, 9-28) months. Compared with patients who reported being not at all bothered by itchy skin, patients who were extremely bothered had a higher rate of all-cause mortality (hazard ratio [HR], 1.24, 95% CI, 1.08-1.41; Fig 3A); the HR in the unadjusted model was 1.59 (95% CI, 1.41-1.81) and was attenuated by adjustment for several potential confounders (Table S3). Patients extremely bothered by itching also had higher rates of CV-related (HR, 1.29; 95% CI, 1.06-1.57) and infection-related mortality (HR, 1.44; 95% CI, 1.05-1.96; Fig 3A). The adjusted rates of all-cause, CV-related, and infection-related hospitalizations were all ∼20% greater for patients extremely bothered versus not at all bothered by itchy skin; the HR for skin-related infections was 1.41 (95% CI, 0.87-2.27) for extremely versus not at all bothered, although the precision of this estimate was limited by the low number of events (Fig 3B). Patients who were extremely versus not at all bothered by itchy skin also had a greater rate of hospitalization for mental status change/confusion (HR, 1.84; 95% CI, 1.18-2.87).

Figure 3.

Association of pruritus with all-cause and cause-specific (A) mortality and (B) hospitalization. Cox regression models stratified by Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) phase and country; adjustments: age, sex, end-stage kidney disease vintage, 15 comorbid conditions, postdialysis weight, albumin level, hemoglobin level, phosphorus level, and catheter use.

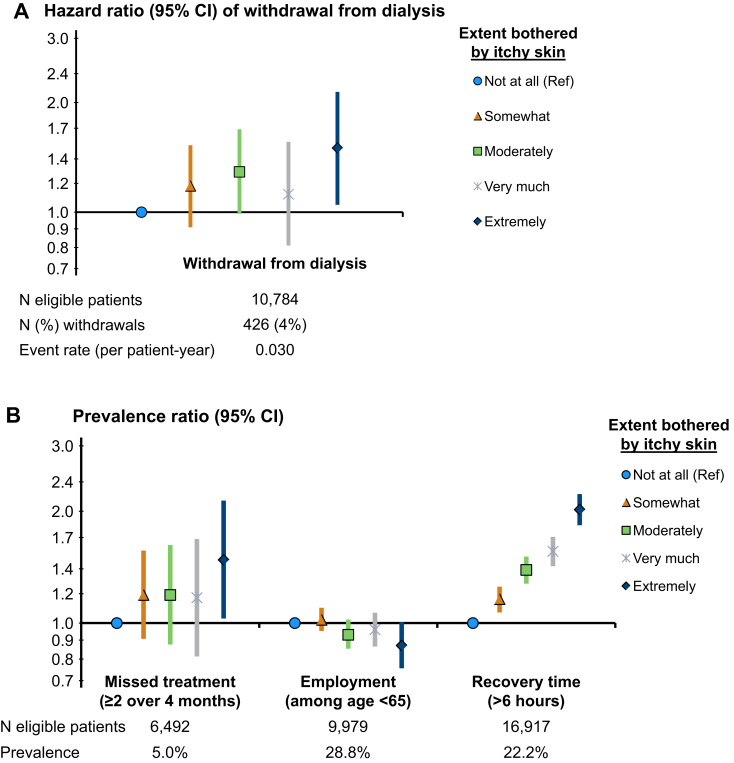

Pruritus and Dialysis-Related Outcomes

The HR for withdrawal from dialysis was 1.50 (95% CI, 1.05-2.14) for patients extremely versus not at all bothered by itchy skin (Fig 4A). Patients who were extremely bothered were also more likely to skip dialysis sessions and less likely to be employed (Fig 4B). A strong monotonic association between severity of itching and self-reported length of recovery time following dialysis sessions was observed (Fig 4B). This association was attenuated after adjustment for self-reported sleep quality, a potential mediator, but remained strong: comparing extremely versus not at all bothered by itchy skin, the prevalence ratio for recovery time longer than 6 hours was 2.02 (95% CI, 1.83-2.22) in the adjusted model and 1.63 (95% CI, 1.48-1.81) after additional adjustment for sleep quality.

Figure 4.

Pruritus and dialysis-related outcomes. Adjustments: age, sex, end-stage kidney disease vintage, 15 comorbid conditions, postdialysis weight, albumin level, hemoglobin level, phosphorus level, and catheter use. (A) Cox model stratified by Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) phase and country; (B) modified Poisson regression with log-link and robust variance estimator, additionally adjusted for DOPPS phase and country.

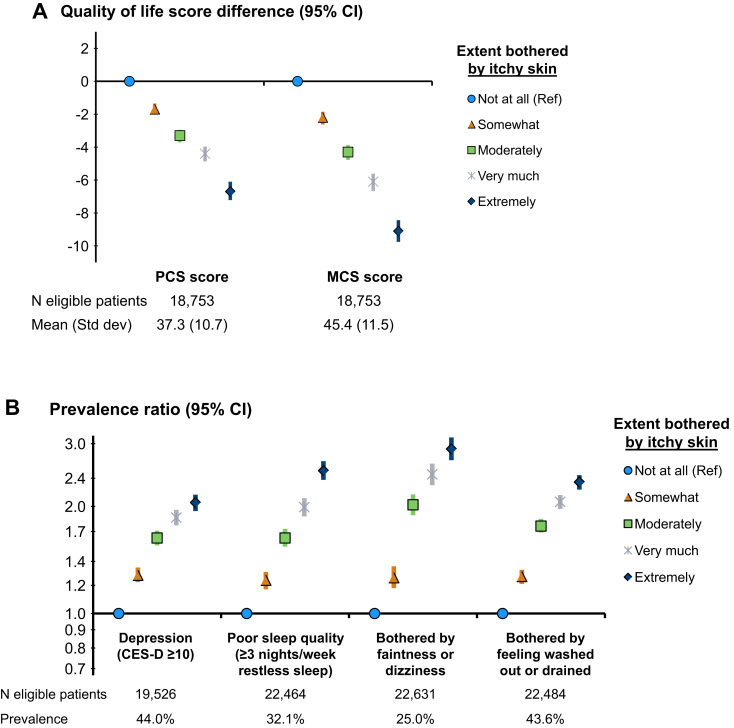

Pruritus and PROs

Self-reported pruritus was strongly associated with both physical and mental components of HR-QoL: PCS and MCS scores were each progressively lower as the severity of pruritus increased (Fig 5A). Mean PCS and MCS scores were 39.2 ± 11.0 (standard deviation) and 48.3 ± 11.4 in patients who were not at all bothered by itchy skin. Compared with this reference group, PCS scores were 6.7 (95% CI, 6.1-7.2) points lower and MCS scores were 9.1 (95% CI, 8.4-9.8) points lower for patients extremely bothered by itchy skin. Other PROs were also strongly and monotonically associated with pruritus; the prevalence of depressive symptoms (CES-D score ≥ 10), poor sleep quality, being bothered by faintness/dizziness, and being bothered by feeling washed out/drained was 2 to 3 times higher among patients extremely versus not at all bothered by itchy skin (Fig 5B).

Figure 5.

Pruritus and patient-reported outcomes. Adjustments: Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) phase, country, age, sex, end-stage kidney disease vintage, 15 comorbid conditions, postdialysis weight, albumin level, hemoglobin level, phosphorus level, and catheter use. (A) Linear mixed models with random facility intercept to account for clustering; (B) modified Poisson regression with log-link and robust variance estimator. Abbreviations: PCS/MCS, Physical/Mental Component Summary, derived from the 12-Item Short Form Health Survey.

Discussion

In this international evaluation of more than 20,000 HD patients, we found that pruritus was common, affecting 37% of patients; associated with higher risk for hospitalizations and death; and associated with higher rates of withdrawal from dialysis and missing scheduled dialysis treatments and lower rates of employment. Additionally, progressively more severe pruritus was strongly and monotonically associated with longer recovery time from dialysis sessions, self-reported depression, self-reported restless sleep, and progressively poorer self-reported mental and physical HR-QoL.

The prevalence of pruritus has declined over the years in the DOPPS, from a 46% prevalence of moderate to extreme pruritus in phase 1 (1996-2001)4 to 37% in phases 4 to 6 (2009-2018), which is shown in this study. The prevalence among phases 4 to 6 has been relatively stable, with some country variation (Fig S1).

Patients more bothered by itchy skin tended to be slightly older, with greater comorbidity, and were more likely to dialyze with a central venous catheter. They also had lower hemoglobin levels, were treated with higher doses of an erythropoiesis-stimulating agent,7 and as in prior studies, had higher C-reactive protein and lower serum albumin levels,3,13,35 consistent with the theory that inflammation may play a role in the pathophysiology of pruritus.19 Dialyzing with a central venous catheter has been associated with higher levels of inflammation.36

There was a trend toward higher serum phosphorus levels with progressive severity of pruritus, as others have shown.7 However, the data are conflicted regarding the relationship between pruritus in patients receiving dialysis and metabolic bone disease parameters, and most studies have found no relationship between pruritus and phosphate levels.4,8,10,18,37, 38, 39, 40 There were no notable differences in parathyroid hormone or calcium levels among the differing levels of pruritus in our study, nor were there large differences identified in dialysis vintage, though it has been shown that patients newer to end-stage kidney disease have lower odds of having moderate to extreme pruritus.3,12,13

We observed a clear association between extreme pruritus and all-cause and cause-specific mortality. The association with cardiovascular mortality may relate to higher levels of inflammation in these patients or possibly the higher prevalence of heart failure, and the infection-related mortality may relate to derangements in the immune system of these patients or the presence of a central venous catheter.36 Those with extreme pruritus had the highest prevalence of catheter use, which may serve to explain in part the higher infection-related mortality seen among those extremely bothered, given the high risk for fatal infections seen in patients with dialysis catheters.41 The association between mortality and pruritus in general has been previously identified.3,12,13 Kimata et al13 showed a 22% higher rate of mortality in the Japanese Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (JDOPPS) for patients moderately to extremely bothered by pruritus (vs not bothered), and adjustment for sleep quality did not serve to explain this association, as it has in other studies.3

We observed a monotonic association between pruritus severity and all-cause hospitalization, with the strongest association observed between extreme pruritus and hospitalization due to mental status change/confusion. However, this should be interpreted with caution because the percentage of patients with a hospitalization due to mental status change/confusion was only 1% (event rate, 0.009). Because this model was adjusted for 15 comorbid conditions (listed in Table 1), these associations are not likely to be explained by the overall illness of the patient but may be linked to central nervous system disturbances associated with pruritus or its treatment.42

It is possible that the association between extreme pruritus and withdrawal from dialysis may be related to the contribution of pruritus to overall symptom burden, which is significant among patients receiving HD43,44 and likely reflected in the large number of patients who withdrew from dialysis in our study. It may also provide a plausible explanation for the association observed between extreme pruritus and missed dialysis treatments, which has been observed previously.7 Conversely, missing dialysis treatments may itself lead to worsening of symptoms because prior studies have shown that higher levels of serum urea nitrogen, a marker of middle-molecule clearance, were associated with more severe pruritus,12 and increasing Kt/V led to an improvement in pruritus.45,46 We found that patients who were extremely (vs not at all) bothered by pruritus had a slightly lower mean Kt/V, though this finding was not consistent with prior DOPPS analyses3,4 and other studies have shown no association between Kt/V and pruritus.7,8,12 Missed dialysis treatments have been associated with increased risk for death,47 and longer interdialytic intervals have been associated with all-cause, cardiac-related, and infection-related mortality.48 The lower prevalence of employment among patients with extreme pruritus may also be linked to the cumulative symptom burden, making it more difficult to sustain or seek employment.

The progressive increase in the prevalence of longer postdialysis recovery time with increasing severity of pruritus, even after adjustment for sleep quality, was striking. Longer recovery time adds not only to the already high symptom burden but also to the psychological burden of living with kidney failure on dialysis14 and may contribute to missed treatments and withdrawal from dialysis. The strong monotonic relationship between pruritus and recovery time suggests that there may be a common neurologic mechanism mediating these symptoms that deserves to be further investigated.

Consistent with prior studies, we show that patients who are more bothered by pruritus have progressively worse self-reported mental and physical HR-QoL3,7,13 and depressive symptoms.3,14 In our study, PCS scores were 6.7 (95% CI, 6.1-7.2) points lower and MCS scores were 9.1 (95% CI, 8.5-9.8) points lower for patients extremely bothered by itchy skin. We regarded 3- to 5-point differences in MCS and PCS scores as clinically relevant.49,50 Although pruritus may lead to depressive symptoms, the reverse is also possible because a longitudinal study by Yamamoto et al51 found that patients with baseline depressive symptoms had higher odds of having severe pruritus when compared with no/mild pruritus (adjusted odds ratio, 1.78; 95% CI, 1.53-2.07).

We confirm previous findings that pruritus is associated with poor sleep quality,3,8,13, 14, 15 as well as feeling washed out or drained.3,13 Patients also had a higher likelihood of dizziness/faintness with progressively greater severity of pruritus, which may be yet another reason for missing treatments and/or withdrawing from dialysis.

There are limitations to this study. First, based on the characteristics of the survey question, this is an observational study assessing the severity of pruritus at one point in time and only during the preceding 4 weeks. Although the change in pruritus severity has been shown over time in the DOPPS,4 we cannot make inferences in how changes in pruritus severity may relate to the outcomes in this study. Though the use of this instrument to measure the severity of pruritus has previously been published with consistent results across many years of DOPPS,1,4,18 it has not yet been formally validated. However, there is much utility in the use of this 1-question scale compared with other longer scales to improve the ease and efficiency for both providers and patients in evaluating this important symptom.

Second, because the severity of pruritus was self-reported, patients may over- or underreport the true severity, leading to possible recall and misclassification bias. Third, the possible bidirectionality of the relationship between pruritus and cross-sectional PROs (eg, depression, missed dialysis sessions, and poor sleep quality) limits the inferences that can be made and does not allow conclusions about cause-effect relationships. Additionally, we did not include treatments of pruritus in our analyses due to potential treatment-by-indication bias and therefore knowledge of how these treatments may relate to the outcomes in this study remains limited. Finally, there were 11,332 (33%) patients who did not respond to the survey or complete the pruritus question, and the sample of patients who responded to the survey was slightly healthier than nonresponders (Table S2), leading to possible nonresponse bias, and because patients more bothered by pruritus are more likely to have comorbid conditions, it is possible that the prevalence of pruritus in our study is underreported.

Patients with CKD underreport their pruritus for reasons that include a lack of awareness of its link with CKD and an acceptance of it as a symptom they must live with.52 Subsequently, health care providers underestimate the prevalence and severity of pruritus,4 and assessment practices vary widely among health care providers.52 This study demonstrates the high prevalence of pruritus among patients receiving HD, as well as the strong associations of pruritus with numerous and diverse clinical outcomes, dialysis-related outcomes, and PROs. The economic burden to dialysis facilities and payers as a result of pruritus and consequent missed HD sessions, hospitalizations, and overall health care use are beyond the scope of this study but deserve further investigation. Our study confirms the importance of identifying patients who experience pruritus, particularly those with severe forms, and underscores the need to identify and treat patients with pruritus effectively to reduce symptom burden and improve quality of life and possibly even survival.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Nidhi Sukul, MD, Angelo Karaboyas, PhD, Philipp A. Csomor, PhD, Thilo Schaufler, MD, Warren Wen, PhD, Frédérique Menzaghi, PhD, Hugh C. Rayner, MD, Takeshi Hasegawa, MD, Issa Al Salmi, MD, Saeed M.G. Al-Ghamdi, MD, Fitsum Guebre-Egziabher, MD, Pablo-Antonio Ureña-Torres, MD, and Ronald L. Pisoni, PhD.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: RLP, TS, AK, HCR, PAC, FM, WW, NS; data acquisition: RLP, IAS; data analysis/interpretation: RLP, TS, AK, P-AU-T, HR, IAS, TH, PC, SMA, FM, WW, NS, FG-E; statistical analysis: RLP, AK; supervision or mentorship: RLP, TS, IAS, FG-E. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision, accepts personal accountability for the author’s own contributions, and agrees to ensure that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

Global support for the ongoing DOPPS Programs is provided without restriction on publications by a variety of funders. For details see https://www.dopps.org/AboutUs/Support.aspx. This manuscript was directly supported by Vifor Pharma, Ltd and Cara Therapeutics, Inc. Drs Karaboyas and Pisoni are employees of Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, which administers the DOPPS.

Financial Disclosure

Dr Karaboyas is an employee of Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, which administers the DOPPS. Drs Csomor and Schaufler are employees of Vifor Pharma Ltd. Drs Wen and Menzaghi are employees of Cara Therapeutics. Dr Hasegawa has consultancy agreements with Kyowa Kirin Corp and received payment or reimbursement of travel/accommodation expenses for expert testimony or lectures (including service on speakers’ bureaus); has a grant by JSPS KAKENHI number 19K03092; and has received honoraria from Kyowa Kirin Corp, Astellas, Baxter, Terumo, and Torii Pharmaceutical. Dr Al Salmi received travel/accommodation expenses to attend various meeting and lectures by Amgen, Roche, Baxter, Abbvie, Diaverum, Sanofi, Fresenius, and Genzyme. Dr Al-Ghamdi has received honorarium for lectures by Abbvie, Sanofi, and Amgen. Dr Ureña-Torres has acted as a consultant for Amgen, Vifor Pharma FMC, and Astellas; is a board member of Amgen, Astellas, and Leo Pharma; and has received payment or reimbursement of travel/accommodation expenses for expert testimony or lectures (including service on speakers’ bureaus) from Amgen and Hemotech. Dr Pisoni is an employee of Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, which administers the DOPPS. The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

Jennifer McCready-Maynes, an employee of Arbor Research Collaborative for Health, provided editorial assistance on this paper.

Peer Review

Received May 20, 2020. Evaluated by 3 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Statistical Editor and the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form August 21, 2020.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

Figure S1: Self-reported pruritus, by DOPPS phase and country

Table S1a: Listing of specific causes of death classified as cardiovascular or infection-related

Table S1b: Listing of specific hospitalization diagnosis and procedure codes classified as cardiovascular, infection, skin-related, or mental status change/confusion

Table S2: Patient characteristics for included vs excluded patients

Table S3: Pruritus and HR (95% CI) of all-cause mortality, by level of adjustment

Supplementary Material

Figure S1; Tables S1-S3.

References

- 1.Sukul N., Speyer E., Tu C. Pruritus and patient reported outcomes in non-dialysis CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019;14(5):673–681. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09600818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solak B., Acikgoz S.B., Sipahi S., Erdem T. Epidemiology and determinants of pruritus in pre-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Int Urol Nephrol. 2016;48:585–591. doi: 10.1007/s11255-015-1208-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pisoni R.L., Wikström B., Elder S.J. Pruritus in haemodialysis patients: international results from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:3495–3505. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfl461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rayner H.C., Larkina M., Wang M. International comparisons of prevalence, awareness, and treatment of pruritus in people on hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12:2000–2007. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03280317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wu H.Y., Huang J.W., Tsai W.C. Prognostic importance and determinants of uremic pruritus in patients receiving peritoneal dialysis: a prospective cohort study. PloS One. 2018;13(9):e0203474. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mistik S., Utas S., Ferahbas A. An epidemiology study of patients with uremic pruritus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20(6):672–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramakrishnan K., Bond T.C., Claxton A. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of end-stage renal disease patients with self-reported pruritus symptoms. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2014;7:1. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S52985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathur V.S., Lindberg J., Germain M., ITCH National Registry Investigators A longitudinal study of uremic pruritus in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:1410–1419. doi: 10.2215/CJN.00100110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satti M., Arshad D., Javed H. Uremic pruritus: prevalence and impact on quality of life and depressive symptoms in hemodialysis patients. Cureus. 2019;11(7):e5178. doi: 10.7759/cureus.5178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amatya B., Agrawal S., Dhali T., Sharma S., Pandey S.S. Pattern of skin and nail changes in chronic renal failure in Nepal: a hospital-based study. J Dermatol. 2008;35:140–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2008.00433.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mettang T., Kremer A.E. Uremic pruritus. Kidney Int. 2015;87:685–691. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Narita I., Aichi B., Omori K. The effect of polymethylmethacrylate dialysis membranes on uremic pruritus. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1626–1632. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kimata N., Fuller D.S., Saito A. Pruritus in hemodialysis patients: results from the Japanese Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (JDOPPS) Hemodial Int. 2014;18(3):657–667. doi: 10.1111/hdi.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lopes G.B., Nogueira F.C., de Souza M.R. Assessment of the psychological burden associated with pruritus in hemodialysis patients using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:603–612. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9964-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tessari G., Dalle Vedove C., Loschiavo C. The impact of pruritus on the quality of life of patients undergoing dialysis: a single centre cohort study. J Nephrol. 2009;22:241–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weiss M., Mettang T., Tschulena U., Weisshaar E. Health-related quality of life in haemodialysis patients suffering from chronic itch: results from GEHIS (German Epidemiology Haemodialysis Itch Study) Qual Life Res. 2016;25:3097–3106. doi: 10.1007/s11136-016-1340-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazeh D., Melamed Y., Cholostoy A., Aharonovitzch V., Weizman A., Yosipovitch G. Itching in the psychiatric ward. Acta Derm Venereol. 2008;88:128–131. doi: 10.2340/00015555-0406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rayner H., Baharani J., Smith S., Suresh V., Dasgupta I. Uraemic pruritus: relief of itching by gabapentin and pregabalin. Nephron Clin Pract. 2012;122:75–79. doi: 10.1159/000349943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimmel M., Alscher D.M., Dunst R. The role of micro-inflammation in the pathogenesis of uraemic pruritus in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2006;21:749–755. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfi204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Combs S.A., Teixeira J.P., Germain M.J. Pruritus in kidney disease. Semin Nephrol. 2015;35(4):383–391. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shirazian S., Aina O., Park Y. Chronic kidney disease-associated pruritus: impact on quality of life and current management challenges. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2017;10:11. doi: 10.2147/IJNRD.S108045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simonsen E., Komenda P., Lerner B. Treatment of uremic pruritus: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(5):638–655. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gunal A.I., Ozalp G., Yoldas T.K., Gunal S.Y., Kirciman E., Celiker H. Gabapentin therapy for pruritus in haemodialysis patients: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19(12):3137–3139. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yue J., Jiao S., Xiao Y., Ren W., Zhao T., Meng J. Comparison of pregabalin with ondansetron in treatment of uraemic pruritus in dialysis patients: a prospective, randomized, double-blind study. Int Urol Nephrol. 2015;47(1):161–167. doi: 10.1007/s11255-014-0795-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fishbane S., Jamal A., Munera C., Wen W., Menzaghi F. A phase 3 trial of difelikefalin in hemodialysis patients with pruritus. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(3):222–232. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young E.W., Goodkin D.A., Mapes D.L. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): an international hemodialysis study. Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;74 doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00387.x. S-74-S-81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pisoni R.L., Gillespie B.W., Dickinson D.M., Chen K., Kutner M.H., Wolfe R.A. The Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS): design, data elements, and methodology. Am J Kidney Dis. 2004;44(suppl 2):7–15. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hays R.D., Kallich J.D., Mapes D.L. Development of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life (KDQOL) instrument. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:329–338. doi: 10.1007/BF00451725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rayner H.C., Zepel L., Fuller D.S. Recovery time, quality of life, and mortality in hemodialysis patients: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;64(1):86–94. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kohout F.J., Berkman L.F., Evans D.A., Cornoni-Huntley J. Two shorter forms of the CES-D Depression Symptoms Index. J Aging Health. 1993;5(2):179–193. doi: 10.1177/089826439300500202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spiegelman D., Hertzmark E. Easy SAS calculations for risk or prevalence ratios and differences. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162(3):199–200. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zou G. A modified Poisson regression approach to prospective studies with binary data. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159(7):702–706. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raghunathan T.E., Solenberger P.W., Van Hoewyk J. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2002. IVEware: Imputation and Variance Estimation Software: User Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Little R.J.A., Rubin D.B. Wiley; 1987. Statistical Analysis With Missing Data. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Virga G., Vesentin I., La Milia V., Bonadonna A. Inflammation and pruritus in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2002;17:2164–2169. doi: 10.1093/ndt/17.12.2164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bossola M., Sanguinetti M., Scribano D. Circulating bacterial-derived DNA fragments and markers of inflammation in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(2):379–385. doi: 10.2215/CJN.03490708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khanna D., Singal A., Kalra O.P. Comparison of cutaneous manifestations in chronic kidney disease with or without dialysis. Postgrad Med J. 2010;86:641–647. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2009.095745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shirazian S., Kline M., Sakhiya V. Longitudinal predictors of uremic pruritus. J Ren Nutr. 2013;23:428–431. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tajbakhsh R., Joshaghani H.R., Bayzayi F., Haddad M., Qorbani M. Association between pruritus and serum concentrations of parathormone, calcium and phosphorus in hemodialysis patients. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2013;24:702–706. doi: 10.4103/1319-2442.113858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duque M.I., Thevarajah S., Chan Y.H., Tuttle A.B., Freedman B.I., Yosipovitch G. Uremic pruritus is associated with higher kt/V and serum calcium concentration. Clin Nephrol. 2006;66:184–191. doi: 10.5414/cnp66184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ravani P., Palmer S.C., Oliver M.J. Associations between hemodialysis access type and clinical outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2013;24(3):465–473. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012070643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Papoiu A.D., Emerson N.M., Patel T.S. Voxel-based morphometry and arterial spin labeling fMRI reveal neuropathic and neuroplastic features of brain processing of itch in end-stage renal disease. J Neurophysiol. 2014;112:1729–1738. doi: 10.1152/jn.00827.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang R., Tang C., Chen X. Poor sleep and reduced quality of life were associated with symptom distress in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14(1):125. doi: 10.1186/s12955-016-0531-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Davison S.N., Jhangri G.S. Impact of pain and symptom burden on the health-related quality of life of hemodialysis patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;39(3):477–485. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hiroshige K., Kabashima N., Takasugi M., Kuroiwa A. Optimal dialysis improves uremic pruritus. Am J Kidney Dis. 1995;25:413–419. doi: 10.1016/0272-6386(95)90102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Orasan O.H., Saplontai A.P., Cozma A. Insomnia, muscular cramps and pruritus have low intensity in hemodialysis patients with good dialysis efficiency, low inflammation and arteriovenous fistula. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49(9):1673–1679. doi: 10.1007/s11255-017-1624-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leggat J.E., Orzol S.M., Hulbert-Shearon T.E. Noncompliance in hemodialysis: predictors and survival analysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;32(1):139–145. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.1998.v32.pm9669435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foley R.N., Gilbertson D.T., Murray T., Collins A.J. Long interdialytic interval and mortality among patients receiving hemodialysis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1099–1107. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1103313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ware J.E., Jr., Kosinksi M., Keller S.D. 2nd ed. The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1994. SF-36 Physical and Mental Health Summary Scales: A User’s Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wyrwich K.W., Bullinger M., Aaronson N., Hays R.D., Patrick D.L., Symonds T. Clinical Significance Consensus Meeting Group. Estimating clinically significant differences in quality of life outcomes. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:285–295. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0705-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamamoto Y., Hayashino Y., Yamazaki S. Depressive symptoms predict the future risk of severe pruritus in haemodialysis patients: Japan Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(2):384–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Aresi G., Rayner H.C., Hassan L. Reasons for underreporting of uremic pruritus in people with chronic kidney disease: a qualitative study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;58(4):578–586. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1; Tables S1-S3.