Abstract

This study examines the prevalence and outcomes of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection among migrant workers in Singapore.

High-density communal residences are at elevated risk of large outbreaks of respiratory disease.1,2 After an initial nationwide outbreak of 231 cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infections in Singapore, which was contained as of March 24, 2020, a surge of 244 cases among migrant workers residing in dormitories, largely from Bangladesh and India, occurred from March 25 to April 7. A national task force was formed to coordinate Singapore’s outbreak response. A national lockdown from April 7 to June 1 enforced movement restriction and confined workers to their dormitories. Medical posts were deployed on-site in all dormitories, and testing capacity for testing and screening residents increased. All workers with a positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test result were admitted to health care facilities for isolation and treatment. We examined the prevalence and outcomes of SARS-CoV-2 infection among migrant workers in Singapore.

Methods

Migrant workers residing in all purpose-built dormitories in Singapore between March 25 and July 25, 2020, were included. Residents who presented with symptoms for medical consultation had nasopharyngeal swabs tested by PCR. Serology on blood samples was also performed for clinical evaluation in selected cases with commercially available kits from Siemens, Abbott, or Roche.3 Screening with PCR was performed in exposed residents, those with medical conditions, and those living in close contact with clustered outbreaks. Toward the end of the outbreak, beginning May 23, testing was performed to determine the status of all residents not previously known to be infected, using a combination of serology and/or PCR, with serology performed in heavily infected dormitories and PCR in less-infected dormitories. Clinical cases were defined as those who presented with symptoms for medical consultation, while subclinical cases were infections found during mass screening among residents without presentation for medical consultation (including workers who never presented for medical consultation or previously symptomatic workers with prior negative test results).

This study was sanctioned by the Singapore Ministry of Health Infectious Disease Act and exempted from institutional review board review because it was conducted as a part of the national public health response to the emerging coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The data were obtained through centralized government databases, including clinical case counts, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, COVID-19–related mortality data, and laboratory results. Statistical analysis (calculation of rates and 95% CIs) was performed using R version 4.0.0.4

Results

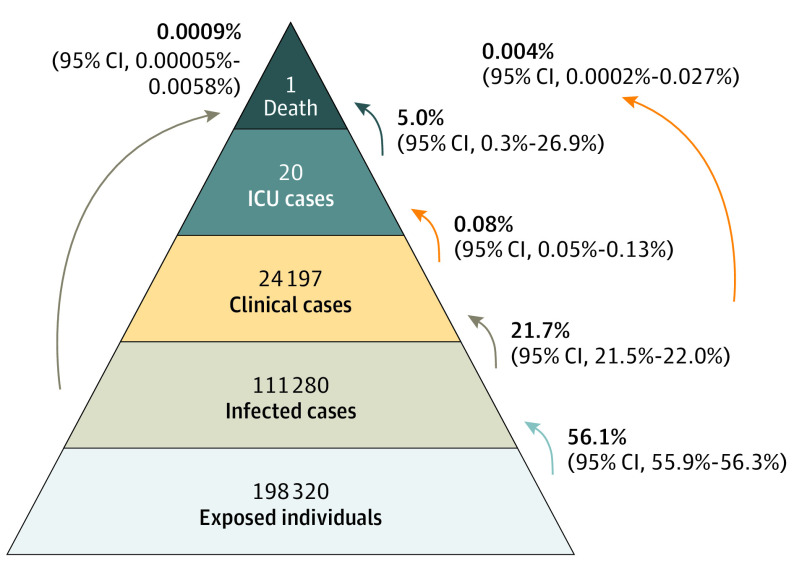

There were 43 dormitories housing 198 320 migrant workers with a median occupancy of 3578 (interquartile range, 1458-6120); 99.8% of residents were male, with a median age of 33 years (interquartile range, 28-39 years). As of July 25, 95.1% of all residents had at least 1 SARS-CoV-2 test, including 63.6% with PCR and 68.4% with serology. There were 111 280 residents with a positive PCR or serology result, for an overall infection prevalence of 56.1% (95% CI, 55.9%-56.3%) (range per dormitory, 0%-74.7%; median, 52.9%) (Figure). There were 24 197 clinical cases (12.2% of all residents; 21.7% of infected) from 42 dormitories and 87 083 subclinical cases (43.9% of all residents; 78.3% of all infected) (Table). Of all clinical cases, 20 cases required ICU admission (0.08% [95% CI, 0.05%-0.13%]), with 1 COVID-19–attributable death (case-fatality rate, 0.004% [95% CI, 0.0002%-0.027%]).

Figure. Overall Disease Severity Spectrum of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 in Migrant Workers in Dormitories in Singapore.

ICU indicates intensive care unit. The death was determined to be coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) related. Data outside of pyramid are rates calculated using standard binomial formulas. Of the 111 280 patients with COVID-19, 1 died (0.0009%) (vs 0.004% of all clinical cases).

Table. Laboratory Tests and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Infection Status of Migrant Workers Residing in Singapore’s Purpose-Built Dormitories (March 25 to July 25, 2020).

| Serology, No. | Total No. (%) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n = 81 548) | Negative (n = 54 212) | Untested (n = 62 560) | ||||||||

| PCR positive | PCR negative | PCR untested | PCR positive | PCR negative | PCR untested | PCR positive | PCR negative | PCR untested | ||

| Clinical infection | 1649 | 2733 | 19 815 | 24 197 (12.2) | ||||||

| Subclinical infection | 262 | 18 183 | 61 454 | 2191 | 4993 | 87 083 (43.9) | ||||

| Uninfected | 48 300 | 988 | 27 943 | 77 231 (38.9) | ||||||

| Untesteda | 9809 | 9809 (4.9) | ||||||||

| Total | 1911 | 18 183 | 61 454 | 4924 | 48 300 | 988 | 24 808 | 27 943 | 9809 | 198 320 |

Abbreviation: PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

As of July 25, 2020.

Discussion

The COVID-19 outbreak among Singapore’s migrant workers was characterized by a high prevalence of infection, low morbidity with few ICU admissions, and low mortality. The low case-fatality rate compares favorably with rates reported in other national registries.5,6 Although migrant workers are younger and generally healthy, the nationally coordinated public health response and clinical care for all cases likely contributed to favorable health outcomes. The infection prevalence would have been severely underestimated if only persons presenting for medical consultation were tested because most infections were subclinical and were identified through mass screening.

Limitations of the study include that some subclinical cases with mild symptoms may have been miscategorized, and incomplete sensitivity of laboratory tests may also have led to an underestimate of prevalence.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

References

- 1.Sloane PD Cruise ships, nursing homes, and prisons as COVID-19 epicenters: a “wicked problem” with breakthrough solutions? J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21(7):958-961. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.04.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yi H, Ng ST, Farwin A, Low PTA, Chang CM, Lim J. Health equity considerations in COVID-19: geospatial network analysis of the COVID-19 outbreak in the migrant population in Singapore. J Travel Med. Published online September 7, 2020. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lisboa Bastos M, Tavaziva G, Abidi SK, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for COVID-19: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;370:m2516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing Accessed June 1, 2020. https://www.R-project.org/

- 5.World Health Organization WHO coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Accessed July 19, 2020. https://covid19.who.int/

- 6.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control COVID-19 surveillance report. Accessed July 19, 2020. https://covid19-surveillance-report.ecdc.europa.eu/