Key Points

Question

Is a restrictive strategy of blood transfusion noninferior to a liberal strategy among patients with acute myocardial infarction and anemia?

Findings

In this randomized clinical trial that included 668 patients with acute myocardial infarction and hemoglobin level between 7 and 10 g/dL who were treated with a restrictive transfusion strategy (triggered by hemoglobin ≤8 g/dL) vs a liberal strategy (triggered by hemoglobin ≤10 g/dL), the composite outcome (all-cause death, stroke, recurrent myocardial infarction, or emergency revascularization) at 30 days occurred in 11% vs 14% of patients, a difference that met the noninferiority criterion of relative risk less than 1.25.

Meaning

A restrictive transfusion strategy compared with a liberal strategy resulted in a noninferior rate of major cardiovascular events among patients with acute myocardial infarction and anemia, but the CI included what may be a clinically important harm.

Abstract

Importance

The optimal transfusion strategy in patients with acute myocardial infarction and anemia is unclear.

Objective

To determine whether a restrictive transfusion strategy would be clinically noninferior to a liberal strategy.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Open-label, noninferiority, randomized trial conducted in 35 hospitals in France and Spain including 668 patients with myocardial infarction and hemoglobin level between 7 and 10 g/dL. Enrollment could be considered at any time during the index admission for myocardial infarction. The first participant was enrolled in March 2016 and the last was enrolled in September 2019. The final 30-day follow-up was accrued in November 2019.

Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned to undergo a restrictive (transfusion triggered by hemoglobin ≤8; n = 342) or a liberal (transfusion triggered by hemoglobin ≤10 g/dL; n = 324) transfusion strategy.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary clinical outcome was major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE; composite of all-cause death, stroke, recurrent myocardial infarction, or emergency revascularization prompted by ischemia) at 30 days. Noninferiority required that the upper bound of the 1-sided 97.5% CI for the relative risk of the primary outcome be less than 1.25. The secondary outcomes included the individual components of the primary outcome.

Results

Among 668 patients who were randomized, 666 patients (median [interquartile range] age, 77 [69-84] years; 281 [42.2%] women) completed the 30-day follow-up, including 342 in the restrictive transfusion group (122 [35.7%] received transfusion; 342 total units of packed red blood cells transfused) and 324 in the liberal transfusion group (323 [99.7%] received transfusion; 758 total units transfused). At 30 days, MACE occurred in 36 patients (11.0% [95% CI, 7.5%-14.6%]) in the restrictive group and in 45 patients (14.0% [95% CI, 10.0%-17.9%]) in the liberal group (difference, −3.0% [95% CI, −8.4% to 2.4%]). The relative risk of the primary outcome was 0.79 (1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.00-1.19), meeting the prespecified noninferiority criterion. In the restrictive vs liberal group, all-cause death occurred in 5.6% vs 7.7% of patients, recurrent myocardial infarction occurred in 2.1% vs 3.1%, emergency revascularization prompted by ischemia occurred in 1.5% vs 1.9%, and nonfatal ischemic stroke occurred in 0.6% of patients in both groups.

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with acute myocardial infarction and anemia, a restrictive compared with a liberal transfusion strategy resulted in a noninferior rate of MACE after 30 days. However, the CI included what may be a clinically important harm.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02648113

This noninferiority trial compares the effects of a restrictive (hemoglobin ≤8 g/dL) vs liberal (hemoglobin ≤10 g/dL) transfusion strategy on 30-day cardiovascular events among adults with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and anemia (hemoglobin 7-10 g/dL).

Introduction

Anemia, with or without overt bleeding, is common in patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and affects prognosis. Even moderate levels of anemia (hemoglobin level of 10-12 g/dL) are associated with increased cardiovascular mortality compared with normal hemoglobin values in the context of acute coronary syndromes.1 Transfusion is often considered to be indicated when the hemoglobin level falls below 10 g/dL, with large variations in clinical practice due to lack of robust data. Observational studies have yielded conflicting results2,3,4 and only 2 small randomized trials (including 45 and 110 patients) have compared restrictive with liberal transfusion strategies in this setting.5,6 Large randomized trials have compared transfusion strategies in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding7 and those undergoing surgical procedures8,9,10 and generally found benefit from a restrictive strategy, but these trials excluded patients with AMI.11

In addition to uncertain benefit in patients with AMI, transfusion has potential adverse effects, logistical implications (particularly for blood supply), and cost. The objective of this study, the Restrictive and Liberal Transfusion Strategies in Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction (REALITY) randomized trial, was to determine whether a restrictive transfusion strategy was clinically noninferior to a liberal transfusion strategy.

Methods

The protocol and statistical analysis plan are presented in Supplement 1. The trial was approved by the Comité de Protection des Personnes, Ile de France-I, France, and the ethics committee at the Hospital Clinic, Barcelona, Spain. Patients provided written informed consent.

Trial Population

To be eligible for inclusion, patients had to be aged at least 18 years and have AMI (with or without ST-segment elevation with a combination of ischemic symptoms occurring in the 48 hours before admission and elevation of biomarkers of myocardial injury) and a hemoglobin level between 7 and 10 g/dL. Enrollment could be considered at any time during the index admission for myocardial infarction. Exclusion criteria were shock at the time of randomization (systolic blood pressure <90 mm Hg with clinical signs of low output or requiring inotropic drugs), myocardial infarction occurring after percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft, life-threatening or massive ongoing bleeding (judged by the investigator), blood transfusion in the past 30 days, and malignant hematologic disease. Given the higher prevalence of chronic anemia in certain ethnic groups, race/ethnicity was recorded (self-reported using fixed categories).

Randomization and Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned in a 1:1 ratio to undergo a restrictive or a liberal transfusion strategy. A web-based randomization system was used, with a centralized block randomization list with blocks of varying size (range, 2-6), stratified by center. In the restrictive strategy group, no transfusion was to be performed unless hemoglobin level decreased to less than or equal to 8 g/dL, with a target range for posttransfusion hemoglobin of 8 to 10 g/dL (the initial protocol used a threshold of 7 g/dL but this was changed to 8 g/dL to maximize investigator adherence to the protocol before inclusion of the first patient). In the liberal strategy group, transfusion was to be performed after randomization on all patients with a hemoglobin level less than or equal to 10 g/dL, with a target posttransfusion hemoglobin level of at least 11 g/dL. Homologous leukoreduced packed red blood cells were used for transfusion.

Both strategies were to be maintained until patient discharge or 30 days after randomization, whichever occurred first. The protocol allowed transfusion to be administered at any time in the following documented instances: massive overt active bleeding, presumed important decrease in hemoglobin level and no time to wait for hemoglobin measurement (indicating suspected massive bleeding), and shock presumably due to blood loss occurring after randomization.

After discharge, patient follow-up was scheduled at day 30 (±5 days) and follow-up data were collected by the investigator, either by direct contact (if the patient was still hospitalized) or by a visit, phone call, or mail. Group assignment was not blinded for data collection.

Outcome Measures and Definitions

The primary clinical efficacy outcome was a composite of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) at 30 days, defined as all-cause death, nonfatal stroke, nonfatal recurrent myocardial infarction, or emergency revascularization prompted by ischemia. Secondary outcomes included the individual components of the composite MACE outcome at 30 days and 1 year. Descriptive end points included the baseline characteristics of patients, use of transfusion, hemoglobin values, and bleeding episodes in each group. The current analysis reports 30-day clinical outcomes. The 1-year outcomes and the cost-effectiveness analyses will be reported separately. Adverse events were monitored during hospital stay and included the following potential adverse effects of transfusion: hemolysis, documented bacteremia acquired after transfusion, multiorgan system dysfunction, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute heart failure, acute kidney failure, and severe allergic reactions. All components of the primary efficacy clinical outcome as well as acute heart failure were adjudicated by a critical event committee blinded to treatment assignment and hemoglobin levels. The third universal definition of myocardial infarction was used.12 All other safety outcomes were investigator-reported. Outcome definitions are detailed in eAppendix 1 in Supplement 2.

Statistical Analysis

Based on unpublished observations from the French nationwide FAST-MI registry of AMI,13,14 we assumed the percentages of patients with MACE at 30 days of approximately 11% in the restrictive transfusion group and 15% in the liberal transfusion group. Noninferiority was assessed using a CI method with a 1-sided 97.5% CI and without any other statistical tests, as recommended by the International Conference on Harmonization.15 The noninferiority margin was set using a relative, rather than absolute, risk margin to minimize the risk of overestimating event rates when planning the trial, because this can make it easy to achieve noninferiority if the overall event rate is lower than expected.16,17 With these assumptions, a sample size of 300 patients per group would provide 80% power to demonstrate noninferiority of the restrictive group, with a margin corresponding to a relative risk equal to 1.25. With a conservative hypothesis of 5% of patients with major protocol violations, 630 patients (315 per group) were required for the trial to be adequately powered for the noninferiority analysis. Because there was no established clinical superiority of either transfusion strategy and no randomized trial of transfusion vs no transfusion, the choice of a noninferiority margin was based on clinical judgment based on what clinicians would be prepared to accept as potential loss of efficacy of a restrictive transfusion strategy compared with a liberal strategy given the expected theoretical benefits of the former of sparing scarce blood resources,18 reducing transfusion adverse effects, and reducing logistical burden and costs. A relative margin of 1.25 appeared an acceptable compromise, given that observational studies relating hemoglobin levels and outcomes after myocardial infarction have shown that the likelihood of MACE increased, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.45 for each 1-g/dL decrement in hemoglobin below 11 g/dL,1 and the expected difference in hemoglobin values between treatment groups would be expected to exceed 1 g/dL.

The analysis of the primary efficacy outcome used relative risk, defined as p1/p2, with p1 = n11/ n1 and p1 = n21/ n2, where n11 is the event number and n1 is the total number of patients in the restrictive group and n21 is the event number and n2 is the total number of patients in the liberal group. Ninety-five percent CIs were estimated using the Wald method. The analysis was performed among both the as-treated population, which included all patients without a major protocol violation (including eligibility criteria not fulfilled), and the as-randomized population, which included all randomized patients with the exception of 2 patients (1 without a consent form and 1 who withdrew consent immediately after randomization). Concordance in the noninferiority analysis between the as-randomized and the as-treated populations was required to establish noninferiority. The use of multiple imputation methods was planned in the statistical analysis plan in the case of missing data for the primary clinical outcome. Given the absence of missing data at day 30, imputation was not needed. Because the trial was conducted at multiple sites, site effect was accounted for in a post hoc sensitivity analysis using a generalized linear regression mixed model with binary distribution and a log link function with strategy as a fixed effect and center as a random effect. If clinical noninferiority of the restrictive strategy was established, a test of superiority of the restrictive strategy was planned.

All secondary analyses were performed on the as-randomized population with available data. In a secondary analysis of the main outcome, survival was estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and groups were compared using a log-rank test. A stratified Cox proportional hazards model was used to estimate the hazard ratios and 95% CIs for the effect of transfusion strategy on MACE-free survival and each component of the MACE outcome. Data for patients with no evidence of MACE were censored at 30 days. The risk proportionality hypothesis was verified by testing the interaction between interest variable and time.

Differences and 95% CIs between strategies were estimated using the Wald method, with continuity correction for binary variables. No adjustment was planned for multiplicity and there was no prespecified hierarchy for secondary efficacy outcomes. Because of the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. The effect of transfusion strategy on the primary composite outcome was explored in subgroups of clinical interest (age, sex, body weight, presence or absence of diabetes, smoking status, presence or absence of hypertension, presence or absence of dyslipidemia, Killip class, kidney function [creatinine clearance], presence or absence of active bleeding, hemoglobin levels at the time of randomization, ST- vs non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, and revascularization by percutaneous coronary intervention for the index event before or after randomization); the interaction between subgroup and transfusion strategy was tested using logistic regression. For safety adverse events, only point estimates of treatment effects with 2-sided 95% CIs are provided. All superiority tests and 95% CI were 2-sided, and P values <.05 were considered significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc) and R version 3.6.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Descriptive Findings

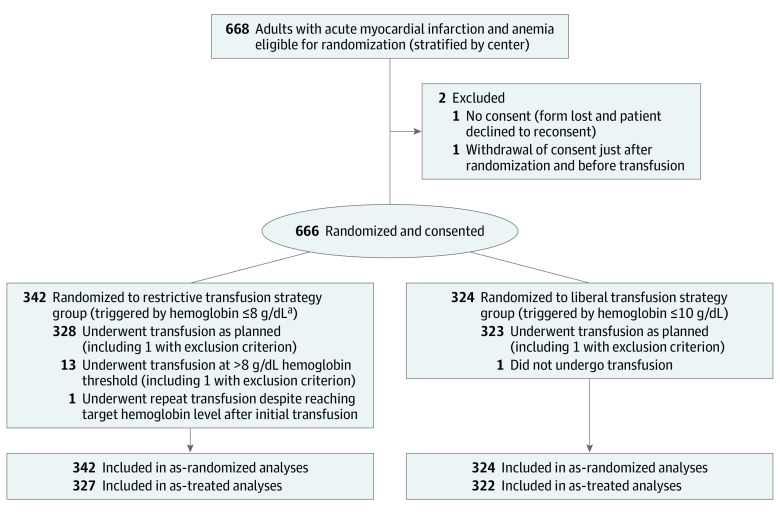

From March 2016 to September 2019, a total of 668 patients with AMI and anemia were consecutively enrolled in the trial (in 26 centers in France and 9 centers in Spain; Figure 1). Baseline characteristics of the as-randomized population were similar between the groups (Table 1). The median age of patients was 77 years, 385 (57.8%) were men, and 334 (50.2%) had diabetes. In most patients, the cause of anemia was unknown; 43 patients (6.5%) had a history of bleeding requiring hospitalization and transfusion. The qualifying myocardial infarction was non–ST-elevation myocardial infarction in approximately two-thirds of the patients. A minority of patients had an identified active bleeding site (Table 1; eTable 1 in Supplement 2).

Figure 1. Flow of Patients in a Study of the Effect of a Restrictive vs Liberal Blood Transfusion Strategy on Major Cardiovascular Events Among Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Anemia.

aThe initial protocol specified a threshold of 7 g/dL. This was changed to 8 g/dL to maximize investigator adherence to the protocol before inclusion of the first patient. Enrollment took place at any time during hospitalization. No screening log was maintained.

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of the As-Randomized Population in a Study of the Effect of a Restrictive vs Liberal Blood Transfusion Strategy on Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Anemia.

| Characteristic | No. (%)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Restrictive (n = 342) | Liberal (n = 324) | |

| Age, median (IQR), y | 78 (69-85) | 76 (69-84) |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 201 (58.8) | 184 (56.8) |

| Women | 141 (41.2) | 140 (43.2) |

| Race (self-reported) | n = 336 | n = 322 |

| White | 298 (88.7) | 266 (82.6) |

| North African | 29 (8.6) | 36 (11.2) |

| African/Caribbean | 7 (2.1) | 9 (2.8) |

| Indian | 2 (0.6) | 5 (1.6) |

| Other Asian | 0 | 6 (1.9) |

| BMI, mean (SD) | 26.9 (5.3) [n = 334] | 26.4 (5.0) [n = 317] |

| Risk factorb | ||

| Hypertension | 272 (79.5) | 256 (79.0) |

| Dyslipidemia | 189 (55.3) | 201 (62.0) |

| Diabetes | 176 (51.5) | 158 (48.8) |

| Tobacco smoking status | n = 316 | n = 293 |

| Never | 149 (47.2) | 141 (48.1) |

| Former | 116 (36.7) | 111 (37.9) |

| Current | 51 (16.1) | 41 (14.0) |

| Family history of premature coronary artery disease | 46 (13.6) [n = 337] | 43 (13.4) [n = 321] |

| Cardiac history before index eventb | ||

| Acute coronary syndrome | 121 (35.4) | 119 (36.7) |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention | 114 (33.3) | 111 (34.3) |

| Angina | 55 (16.1) | 44 (13.6) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 54 (15.8) | 65 (20.1) |

| CABG | 44 (12.9) | 42 (13.0) |

| Congestive heart failure | 44 (12.9) | 38 (11.7) |

| Internal cardiac defibrillator | 14 (4.1) | 8 (2.5) |

| Noncardiac medical historyb | ||

| Chronic anemiac | 61 (17.8) | 62 (19.1) |

| Cancer | ||

| Previously treated | 42 (12.3) | 44 (13.6) |

| Receiving treatment | 25 (7.3) | 18 (5.6) |

| COPD | 34 (9.9) | 40 (12.3) |

| Dialysis | 25 (7.3) | 30 (9.3) |

| History of bleeding requiring hospitalization and transfusion | 23 (6.7) | 20 (6.2) |

| Index hospitalization | ||

| Myocardial infarction type | ||

| Non–ST-segment elevation | 234 (68.4) | 231 (71.3) |

| ST-segment elevation | 108 (31.6) | 93 (28.7) |

| Killip class at admissiond | n = 336 | n = 321 |

| I | 189 (56.3) | 183 (57.0) |

| II | 87 (25.9) | 88 (27.4) |

| III | 54 (16.1) | 39 (12.1) |

| IV | 6 (1.8) | 11 (3.4) |

| Delay between admission and randomization, median (IQR), d | 1.6 (0.8-3.6) | 1.9 (0.8-3.6) |

| Active bleedinge | 36 (10.5) | 49 (15.1) |

| 1 active bleed | 29 (80.6) | 42 (85.7) |

| 2 active bleeds | 6 (16.7) | 6 (12.2) |

| 3 active bleeds | 1 (2.8) | 1 (2.0) |

| Creatinine clearance at randomization,f median (IQR), mL/min/1.73 m2 | 45.1 (27.2-73.2) [n = 338] | 46.6 (24.9-73.2) [n = 321] |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared); CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

Collected through chart review.

Preexisting anemia not caused by acute bleeding.

Killip class was determined by the investigator according to clinical examination. Class I indicates no sign of congestion; class II, basal rales on auscultation; class III, acute pulmonary edema; and class IV, cardiogenic shock.

Active bleeding identified and documented during the index admission prior to randomization.

According to the Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration formula.

In-hospital management is detailed in eTable 2 in Supplement 2. Most patients underwent coronary angiography (81.9% in the restrictive group and 79.3% in the liberal group) and approximately two-thirds underwent myocardial revascularization. Treatments before hospitalization and during the first 24 hours of admission are shown in eTable 3 in Supplement 2. Most patients received dual antiplatelet therapy for the qualifying myocardial infarction. Baseline characteristics and treatment of the as-treated population are shown in eTable 4 in Supplement 2 and were consistent with the as-randomized population.

Hemoglobin levels were similar in both groups at admission and at randomization (Table 2). A total of 122 patients (35.7%) in the restrictive group and 323 (99.7%) in the liberal group received at least 1 transfusion. The distribution of the number of red blood cell units transfused per patient is shown in Table 2. In the liberal group, the majority of patients received 2 or more units. The restrictive group used 342 red blood cell units and the liberal group used 758. Few patients received concomitant fresh frozen plasma or platelet transfusion. The in-hospital hemoglobin nadir was lower in the restrictive group than the liberal group.

Table 2. Hemoglobin Levels and Transfusions Among the As-Randomized Population in a Study of the Effect of a Restrictive vs Liberal Blood Transfusion Strategy on Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Anemia.

| Variable | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Restrictive (n = 342) | Liberal (n = 324) | |

| Hemoglobin level, mean (SD), g/dL | ||

| At admission | 10.0 (1.7) | 10.1 (1.6) [n = 322] |

| Most recent prior to randomization | 9.0 (0.8) | 9.1 (0.8) [n = 323] |

| Lowest value during hospital stay | 8.3 (0.9) | 8.8 (0.9) [n = 323] |

| At discharge | 9.7 (1.0) [n = 337] | 11.1 (1.4) [n = 320] |

| Red blood cell transfusion | ||

| Patients who received ≥1 unit of packed red blood cells | 122 (35.7) | 323 (99.7)a |

| Units transfused, No. | 342 | 758 |

| Per patient transfused, mean (SD) | 2.9 (3.7) | 2.8 (2.7) |

| Per patient transfused, median (IQR) | 2.0 (2.0-3.0) | 2.0 (2.0-3.0) |

| Units transfused | ||

| 0 | 220 (64.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| 1 | 25 (7.3) | 43 (13.3) |

| 2 | 62 (18.1) | 128 (39.5) |

| 3 | 12 (3.5) | 47 (14.5) |

| ≥4 | 19 (5.6) | 54 (16.7) |

| ≥1 (exact No. not available) | 4 (1.2) | 51 (15.7) |

| Duration of red blood cell storage, median (IQR), d | 20.0 (17.0-25.0) | 21.0 (15.0-30.0) |

| No. of units for which data were available | 90 | 299 |

| Transfusion | ||

| Fresh frozen plasma | 3 (0.9) | 7 (2.2) |

| Platelet | 4 (1.2) | 6 (1.9) |

Abbreviation: IQR, interquartile range.

One patient had been transferred to a non–study site where local physicians declined to implement transfusion.

The median (interquartile range) length of hospitalization was 7.0 (3.0-13.0) days in both groups; 56 patients in both the restrictive strategy (16.4%) and liberal strategy (17.3%) groups were hospitalized in an intensive care unit. At discharge, mean (SD) hemoglobin was 9.7 (1.0) g/dL in the restrictive group compared with 11.1 (1.4) g/dL in the liberal group (difference, −1.4 [95% CI, −1.6 to −1.2]; Table 2). Data for the as-treated population are provided in eTable 5 in Supplement 2.

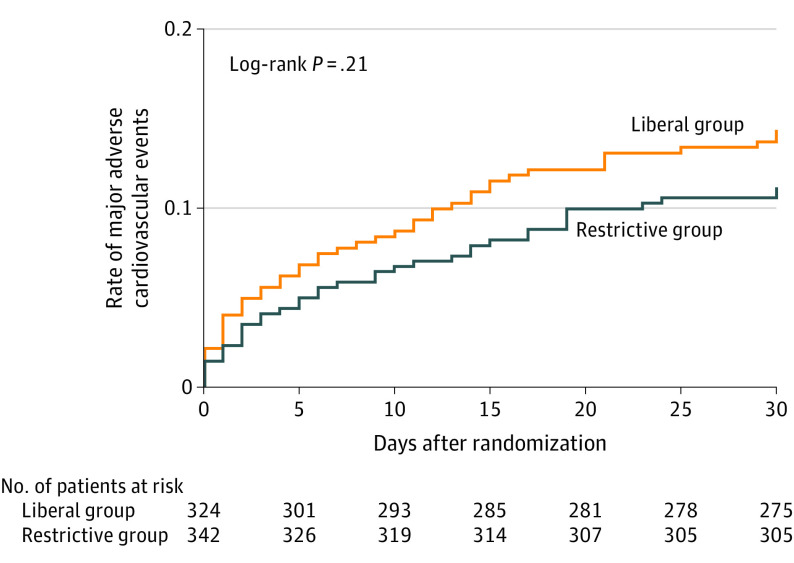

Primary Efficacy Outcome

Follow-up data for 30-day MACE were complete for all 666 patients who consented and were randomized. In the as-treated population, 30-day MACE occurred in 36 patients (11.0% [95% CI, 7.5%-14.6%]) in the restrictive group and in 45 patients (14.0% [95% CI, 10.0%-17.9%]) in the liberal group (relative risk, 0.79 [1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.00-1.19]), fulfilling the criterion for noninferiority (Table 3). Noninferiority of the restrictive strategy was also achieved in the as-randomized population (relative risk, 0.78 [1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.00-1.17]). Similar results were found in post hoc sensitivity analyses accounting for site effects (as-treated population: relative risk, 0.79 [1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.00-1.18]; as-randomized population: relative risk, 0.78 [1-sided 97.5% CI, 0.00-1.17]). In the planned sequential superiority analysis performed among the as-randomized population (Figure 2), the restrictive strategy did not meet criteria for superiority compared with the liberal strategy (upper bound of 1-sided 97.5% CI >1.00).19 Subgroup analyses based on age; sex; body weight; smoking status; Killip class; kidney function (creatinine clearance); type of myocardial infarction (ST- vs non–ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction); presence or absence of diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, and active bleeding; and hemoglobin levels at the time of randomization yielded results consistent with the main analysis, and results of the tests for interaction were not statistically significant (eFigure in Supplement 2).

Table 3. Primary and Secondary Outcomes at 30 Days Among the As-Randomized Population in a Study of the Effect of a Restrictive vs Liberal Blood Transfusion Strategy on Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Anemia.

| Outcome | No. (%) | Difference (95% CI), % | Relative risk (1-sided 97.5% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Restrictive | Liberal | |||

| Primary (major adverse cardiovascular events), No./total No. (%) [95% CI]a | ||||

| As-treated population | 36/327 (11.0) [7.5 to 14.6] | 45/322 (14.0) [10.0 to 17.9] | −3.0 (−8.4 to 2.4) | 0.79 (0.00 to 1.19) |

| As-randomized population | 38/342 (11.1) [7.6 to 14.6] | 46/324 (14.2) [10.2 to 18.2] | −3.1 (−8.4 to 2.3) | 0.78 (0.00 to 1.17) |

| Secondary (individual outcomes in the as-randomized population)b | n = 342 | n = 324 | ||

| All-cause death | 19 (5.6) | 25 (7.7) | ||

| Cardiovascular | 13 (68.4) | 21 (84.0) | ||

| Noncardiovascular | 3 (15.8) | 2 (8.0) | ||

| Unknown | 3 (15.8) | 2 (8.0) | ||

| Nonfatal recurrent myocardial infarctionc | 7 (2.1) | 10 (3.1) | ||

| ST-segment elevation recurrent myocardial infarction | 0 | 3 (30.0) | ||

| Non–ST-segment elevation recurrent myocardial infarction | 7 (100.0) | 7 (70.0) | ||

| Type 1: spontaneous recurrent myocardial infarction | 4 (57.1) | 4 (40.0) | ||

| Type 2: recurrent myocardial infarction secondary to an ischemic imbalance | 2 (28.6) | 5 (50.0) | ||

| Type 4b: recurrent myocardial infarction related to stent thrombosis | 1 (14.3) | 1 (10.0) | ||

| Emergency revascularization | 5 (1.5) | 6 (1.9) | ||

| Nonfatal ischemic stroke | 2 (0.6) | 2 (0.6) | ||

Composite of all-cause death, stroke, recurrent myocardial infarction, or emergency revascularization prompted by ischemia at 30 days.

Given the potential for type I error due to multiple comparisons, no formal statistical comparisons were made for secondary outcomes.

Type of myocardial infarction was adjudicated by a blinded event committee, according to the third universal definition of myocardial infarction.12

Figure 2. Rate of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in a Study of the Effect of a Restrictive vs Liberal Blood Transfusion Strategy Among Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Anemia.

Results shown are of analyses including the as-randomized population. All patients were followed up to the first event or 30 days. Major adverse cardiovascular events are a composite of all-cause death, stroke, recurrent myocardial infarction, or emergency revascularization prompted by ischemia.

Secondary Efficacy Outcomes

Components of 30-day MACE are detailed in Table 3. In the restrictive group vs the liberal group, all-cause death occurred in 5.6% vs 7.7% of patients, recurrent myocardial infarction occurred in 2.1% vs 3.1% of patients, emergency revascularization prompted by ischemia occurred in 1.5% vs 1.9% of patients, and nonfatal ischemic stroke occurred in 0.6% of patients in both groups. Secondary outcomes in the as-treated population are provided in eTable 6 in Supplement 2.

Adverse Events

Adverse events are presented in Table 4 for the as-randomized population and in eTable 6 in Supplement 2 for the as-treated population.

Table 4. Adverse Events Among the As-Randomized Population in a Study of the Effect of a Restrictive vs Liberal Blood Transfusion Strategy on Patients With Acute Myocardial Infarction and Anemia.

| Adverse event | No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Restrictive (n = 342) | Liberal (n = 324) | |

| At least 1 adverse event | 40 (11.7) | 36 (11.1) |

| Acute kidney injurya | 33 (9.7) | 23 (7.1) |

| Acute heart failureb | 11 (3.2) | 12 (3.7) |

| Severe allergic reactiona | 3 (0.9) | 0 |

| Acute lung injury/ARDSa | 1 (0.3) | 7 (2.2) |

| Multiorgan system dysfunctiona | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.9) |

| Infectiona,c | 0 | 5 (1.5) |

Abbreviation: ARDS, acute respiratory distress syndrome.

According to investigator judgment.

Adjudicated according to the following criteria: new or worsening symptoms due to congestive heart failure, objective evidence of new congestive heart failure (physical examination, laboratory, imaging or hemodynamic evidence), and initiation or intensification of chronic heart failure treatment.

Documented bacterial infection/bacteremia acquired at any time after the first transfusion.

Discussion

Among patients with AMI and anemia, a restrictive compared with a liberal transfusion strategy resulted in a noninferior rate of MACE after 30 days. However, the CI included what may be a clinically important harm.

Anemia is common in patients with AMI and is associated with worse clinical outcomes.1 In theory, transfusion should increase oxygen delivery, which would argue for a liberal transfusion strategy in patients with acute myocardial ischemia. However, data suggest that oxygen delivery is not necessarily increased in patients receiving transfusions, due to red blood cell depletion in nitric oxide and 2,3-diphosphoglyceric acid during storage, and that, conversely, transfusion may increase platelet activation and aggregation and produce vasoconstriction.20,21 Observational studies have yielded uncertain results and are susceptible to unmeasured confounding,22 highlighting the need for randomized trials.23 To our knowledge, only 2 small randomized trials that examine transfusion in individuals with myocardial infarction are available, and they reported opposite conclusions. The first trial, which included 45 patients, found apparent benefit of a restrictive over a liberal transfusion strategy and the second pilot trial, which included 110 patients, found numerically fewer cardiac events and deaths with a liberal strategy, but no statistically significant difference, and led the authors to support the need for a definitive trial.6,22 There is wide variation in clinical practice regarding the use of transfusion for patients with AMI.24 Given the persistent equipoise in the clinical community regarding what transfusion strategy is optimal in the specific setting of AMI, there have been multiple calls for generating more evidence from randomized trials.4,11,22,25

Uncertainty exists on the optimal transfusion strategy and on what hemoglobin level should trigger transfusion in this population. In patients with AMI and anemia, the current trial showed statistical noninferiority of the restrictive strategy compared with the liberal strategy in both the as-randomized and as-treated populations, providing some confidence in the results.26 However, determination of the margin used to declare noninferiority is critical to the interpretation of the result. This determination can be based on computation of preservation of at least a fraction of the benefit of an established treatment (often in the range of 50% preservation of the benefit). In the case of AMI, no trial to our knowledge has compared transfusion with no transfusion. However, a large observational analysis of the relationship between anemia and mortality after AMI showed that the risk of MACE increased, with an adjusted odds ratio of 1.45 (95% CI, 1.33-1.58) for each 1-g/dL decrement in hemoglobin below 11 g/dL.1 A 25% relative noninferiority margin would preserve a substantial fraction of the expected benefit of transfusion, because the anticipated difference in hemoglobin value was expected to exceed 1 g/dL (as was actually observed). The noninferiority margin should also be justifiable on clinical grounds based on the estimate of what clinicians would find clinically acceptable as a potential loss of efficacy with an “experimental” strategy compared with an established strategy, given the benefits of the former. In the present setting, the theoretical advantages of the restrictive strategy would be reduced consumption of increasingly scarce blood resources,18 reduced adverse effects from transfusion, potential cost savings, and logistical benefits related to the implementation of transfusion. The choice of a 25% relative increase as the margin for noninferiority was more conservative than the margin used in many recent large trials,27,28,29,30,31 but did not eliminate inferiority. In any case, it is recommended that clinicians use their own judgment in interpreting noninferiority thresholds.32 Although the 30-day primary clinical outcome was numerically lower with the restrictive strategy, this difference did not achieve statistical significance for superiority. Although the decision to initiate transfusion should not be based on hemoglobin level alone, the observed result suggests there may be merit to a restrictive strategy, which had no apparent downside in terms of logistics. Heart rate was not factored in the decision to initiate transfusion, particularly because most patients with AMI receive β-blockers.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it was of moderate size and thus was not powered for evaluating the superiority of either strategy. A noninferiority margin of 1.25 includes potentially clinically important harm and may be considered too large. Even the observed confidence limit ranges up to an 18% increase in cardiac events, which would be clinically meaningful. A larger trial with a similar clinical design is ongoing in individuals with AMI (MINT trial; NCT02981407) and is powered for clinical superiority using the composite outcome of all-cause mortality and nonfatal recurrent AMI. Second, the trial was open-label due to the logistical challenges of blinding transfusion in the setting of AMI. However, assessment of clinical efficacy relied on objective outcomes, which were blindly adjudicated. Third, because qualifying hemoglobin levels could be collected at any time during hospitalization, some patients may have qualified for enrollment due to shifts after catheterization, repeated blood draws during a long stay, or active bleeding from medications or procedures. Therefore, a mixture of individuals with anemia, bleeding, and dilution were included in the eligible population.33 However, subgroup analyses based on the presence or absence of preexisting anemia or of active bleeding yielded results consistent with the main analysis. Fourth, this report was limited to analysis of 30-day outcomes. Longer follow-up to 1 year is being accrued and will allow evaluation of the potential long-term effects of the 2 transfusion strategies as well as assessment of potential quality of life and incremental cost-utility ratio differences between the groups.34

Conclusions

Among patients with AMI and anemia, a restrictive compared with liberal transfusion strategy resulted in a noninferior rate of major cardiovascular events after 30 days. However, the CI included what may be a clinically important harm.

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan

eAppendix

eTables

eFigure

eReferences

Data sharing statement

References

- 1.Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, Giugliano RP, et al. . Association of hemoglobin levels with clinical outcomes in acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2005;111(16):2042-2049. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000162477.70955.5F [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu WC, Rathore SS, Wang Y, Radford MJ, Krumholz HM. Blood transfusion in elderly patients with acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345(17):1230-1236. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatterjee S, Wetterslev J, Sharma A, Lichstein E, Mukherjee D. Association of blood transfusion with increased mortality in myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis and diversity-adjusted study sequential analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(2):132-139. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamainternmed.1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carson JL, Carless PA, Hébert PC. Outcomes using lower vs higher hemoglobin thresholds for red blood cell transfusion. JAMA. 2013;309(1):83-84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.50429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper HA, Rao SV, Greenberg MD, et al. . Conservative versus liberal red cell transfusion in acute myocardial infarction (the CRIT randomized pilot study). Am J Cardiol. 2011;108(8):1108-1111. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson JL, Brooks MM, Abbott JD, et al. . Liberal versus restrictive transfusion thresholds for patients with symptomatic coronary artery disease. Am Heart J. 2013;165(6):964-971. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villanueva C, Colomo A, Bosch A, et al. . Transfusion strategies for acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(1):11-21. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Docherty AB, O’Donnell R, Brunskill S, et al. . Effect of restrictive versus liberal transfusion strategies on outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease in a non-cardiac surgery setting: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2016;352:i1351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murphy GJ, Pike K, Rogers CA, et al. ; TITRe2 Investigators . Liberal or restrictive transfusion after cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(11):997-1008. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1403612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mazer CD, Whitlock RP, Fergusson DA, et al. ; TRICS Investigators and Perioperative Anesthesia Clinical Trials Group . Six-month outcomes after restrictive or liberal transfusion for cardiac surgery. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(13):1224-1233. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1808561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rao SV, Sherwood MW. Isn’t it about time we learned how to use blood transfusion in patients with ischemic heart disease? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(13):1297-1299. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, et al. ; Joint ESC/ACCF/AHA/WHF Task Force for the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction . Third universal definition of myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2012;126(16):2020-2035. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31826e1058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Puymirat E, Simon T, Steg PG, et al. ; USIK USIC 2000 Investigators; FAST MI Investigators . Association of changes in clinical characteristics and management with improvement in survival among patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2012;308(10):998-1006. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanssen M, Cottin Y, Khalife K, et al. ; FAST-MI 2010 Investigators . French registry on acute ST-elevation and non ST-elevation myocardial infarction 2010: FAST-MI 2010. Heart. 2012;98(9):699-705. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2012-301700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Statistical Principles for Clinical Trials European Medicines Agency ; 1998. Accessed November 18, 2020. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/ich-e9-statistical-principles-clinical-trials

- 16.Steg PG, Simon T. Duration of antiplatelet therapy after DES implantation: can we trust non-inferiority open-label trials? Eur Heart J. 2017;38(14):1044-1047. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pocock SJ, Clayton TC, Stone GW. Challenging issues in clinical trial design: part 4 of a 4-part series on statistics for clinical trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(25):2886-2898. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.10.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williamson LM, Devine DV. Challenges in the management of the blood supply. Lancet. 2013;381(9880):1866-1875. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60631-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Non-Inferiority Clinical Trials to Establish Effectiveness: Guidance for Industry US Food and Drug Administration ; 2016. Accessed August 3, 2020. https://www.fda.gov/media/78504/download

- 20.Silvain J, Pena A, Cayla G, et al. . Impact of red blood cell transfusion on platelet activation and aggregation in healthy volunteers: results of the TRANSFUSION study. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(22):2816-2821. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Silvain J, Abtan J, Kerneis M, et al. . Impact of red blood cell transfusion on platelet aggregation and inflammatory response in anemic coronary and noncoronary patients: the TRANSFUSION-2 study (impact of transfusion of red blood cell on platelet activation and aggregation studied with flow cytometry use and light transmission aggregometry). J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(13):1289-1296. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeh RW, Wimmer NJ. Blood transfusion in myocardial infarction: opening old wounds for comparative-effectiveness research. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64(8):820-822. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao SV, Jollis JG, Harrington RA, et al. . Relationship of blood transfusion and clinical outcomes in patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA. 2004;292(13):1555-1562. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.13.1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alexander KP, Chen AY, Wang TY, et al. ; CRUSADE Investigators . Transfusion practice and outcomes in non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes. Am Heart J. 2008;155(6):1047-1053. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Farhan S, Baber U, Mehran R. Anemia and acute coronary syndrome: time for intervention studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(11):e004908. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piaggio G, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, Pocock SJ, Evans SJ; CONSORT Group . Reporting of noninferiority and equivalence randomized trials: an extension of the CONSORT statement. JAMA. 2006;295(10):1152-1160. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.10.1152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim HS, Kang J, Hwang D, et al. ; HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS investigators . Prasugrel-based de-escalation of dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (HOST-REDUCE-POLYTECH-ACS): an open-label, multicentre, non-inferiority randomised trial. Lancet. 2020;396(10257):1079-1089. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31791-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watanabe H, Domei T, Morimoto T, et al. ; STOPDAPT-2 Investigators . Effect of 1-Month dual antiplatelet therapy followed by clopidogrel vs 12-month dual antiplatelet therapy on cardiovascular and bleeding events in patients receiving PCI: the STOPDAPT-2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(24):2414-2427. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.8145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kedhi E, Fabris E, van der Ent M, et al. . Six months versus 12 months dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stent implantation in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (DAPT-STEMI): randomised, multicentre, non-inferiority trial. BMJ. 2018;363:k3793. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hahn JY, Song YB, Oh JH, et al. ; SMART-DATE investigators . 6-Month versus 12-month or longer dual antiplatelet therapy after percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with acute coronary syndrome (SMART-DATE): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;391(10127):1274-1284. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30493-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jabre P, Penaloza A, Pinero D, et al. . Effect of bag-mask ventilation vs endotracheal intubation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation on neurological outcome after out-of-hospital cardiorespiratory arrest: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319(8):779-787. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.0156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mulla SM, Scott IA, Jackevicius CA, You JJ, Guyatt GH. How to use a noninferiority trial: users’ guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 2012;308(24):2605-2611. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ducrocq G, Puymirat E, Steg PG, et al. . Blood transfusion, bleeding, anemia, and survival in patients with acute myocardial infarction: FAST-MI registry. Am Heart J. 2015;170(4):726-734. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ducrocq G, Calvo G, González-Juanatey JR, et al. . Restrictive versus liberal red blood cell transfusion strategies in patients with acute myocardial infarction and anemia: rationale and design of the REALITY trial. Clin Cardiol. Published online January 6, 2021. doi: 10.1002/clc.23453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial protocol and statistical analysis plan

eAppendix

eTables

eFigure

eReferences

Data sharing statement