Key Points

Question

Is there a difference in change in peak oxygen consumption (V̇o2) among patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) treated with differing modes of exercise?

Findings

This randomized clinical trial included 180 patients with HFpEF assigned to high-intensity interval training, moderate continuous training, or a control of guideline-based physical activity advice. At 3 months, the changes in peak V̇o2 were 1.1, 1.6, and −0.6 mL/kg/min, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between high-intensity interval and moderate continuous training, and neither group met the a priori–defined minimal clinically important difference of 2.5 mL/kg/min compared with the guideline control.

Meaning

These findings do not support either high-intensity interval training or moderate continuous training compared with guideline-based physical activity for patients with HFpEF.

Abstract

Importance

Endurance exercise is effective in improving peak oxygen consumption (peak V̇o2) in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). However, it remains unknown whether differing modes of exercise have different effects.

Objective

To determine whether high-intensity interval training, moderate continuous training, and guideline-based advice on physical activity have different effects on change in peak V̇o2 in patients with HFpEF.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized clinical trial at 5 sites (Berlin, Leipzig, and Munich, Germany; Antwerp, Belgium; and Trondheim, Norway) from July 2014 to September 2018. From 532 screened patients, 180 sedentary patients with chronic, stable HFpEF were enrolled. Outcomes were analyzed by core laboratories blinded to treatment groups; however, the patients and staff conducting the evaluations were not blinded.

Interventions

Patients were randomly assigned (1:1:1; n = 60 per group) to high-intensity interval training (3 × 38 minutes/week), moderate continuous training (5 × 40 minutes/week), or guideline control (1-time advice on physical activity according to guidelines) for 12 months (3 months in clinic followed by 9 months telemedically supervised home-based exercise).

Main Outcomes and Measures

Primary end point was change in peak V̇o2 after 3 months, with the minimal clinically important difference set at 2.5 mL/kg/min. Secondary end points included changes in metrics of cardiorespiratory fitness, diastolic function, and natriuretic peptides after 3 and 12 months.

Results

Among 180 patients who were randomized (mean age, 70 years; 120 women [67%]), 166 (92%) and 154 (86%) completed evaluation at 3 and 12 months, respectively. Change in peak V̇o2 over 3 months for high-intensity interval training vs guideline control was 1.1 vs −0.6 mL/kg/min (difference, 1.5 [95% CI, 0.4 to 2.7]); for moderate continuous training vs guideline control, 1.6 vs −0.6 mL/kg/min (difference, 2.0 [95% CI, 0.9 to 3.1]); and for high-intensity interval training vs moderate continuous training, 1.1 vs 1.6 mL/kg/min (difference, −0.4 [95% CI, −1.4 to 0.6]). No comparisons were statistically significant after 12 months. There were no significant changes in diastolic function or natriuretic peptides. Acute coronary syndrome was recorded in 4 high-intensity interval training patients (7%), 3 moderate continuous training patients (5%), and 5 guideline control patients (8%).

Conclusions and Relevance

Among patients with HFpEF, there was no statistically significant difference in change in peak V̇o2 at 3 months between those assigned to high-intensity interval vs moderate continuous training, and neither group met the prespecified minimal clinically important difference compared with the guideline control. These findings do not support either high-intensity interval training or moderate continuous training compared with guideline-based physical activity for patients with HFpEF.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02078947

This randomized trial compares the effects of high-intensity interval training, moderate continuous training, and guideline-based physical activity on change in peak oxygen consumption (V̇o2) in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) affects more than 2% of the global adult population and resulted in 809 000 hospitalizations in the US in 2016.1 An analysis of 28 820 patients from different cohort studies2 (inclusion between 1979 and 2002; followed for up to 15 years) demonstrated that approximately 50% of patients with incident HF had a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and based on data from community surveillance in 4 US communities (2005 to 2009), 47% of hospitalizations for incident HF events were due to HFpEF.3 The prevalence of HFpEF is projected to further increase, primarily driven by an aging population.1 Additional risk factors include hypertension, previous myocardial infarction, diabetes, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle.2,4

A cardinal feature of HFpEF is reduced exercise tolerance associated with reduced quality of life (QoL).5 While pharmacological therapy for HFpEF has been unsuccessful,6 exercise training has been shown to be effective in improving maximal exercise capacity assessed as peak oxygen consumption (peak V̇o2) in clinically stable patients with HFpEF. However, the few trials performed to date have only involved smaller sample sizes (≤100 patients) and limited exercise intervention periods (≤24 weeks).7,8,9,10 To date, only 1 trial in 11 patients with HFpEF examined the effect of a 1-year exercise intervention.11 Moreover, high-intensity interval training may be superior to traditionally prescribed moderate continuous training to improve peak V̇o2 and diastolic function in these patients.9,10,12

Given the uncertainty of the role of exercise intensity and duration of training in HFpEF, the aim of this trial was to test whether high-intensity interval training, moderate continuous training, and guideline-based advice on physical activity (guideline control) result in different changes in peak V̇o2 and other cardiopulmonary exercise test parameters, indices of left ventricular (LV) diastolic function, N-terminal pro–brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), and QoL after 3 and 12 months.

Methods

Trial Oversight

OptimEx-Clin (Optimizing Exercise Training in Prevention and Treatment of Diastolic Heart Failure; European OptimEx Consortium; European Framework Program 7, grant No. EU 602405-2) was a randomized, multicenter trial with 3 groups conducted at 5 European sites (Berlin, Leipzig, and Munich, Germany; Antwerp, Belgium; and Trondheim, Norway) assessing different exercise intensities in patients with HFpEF over 3 months in clinic followed by 9 months of telemedically supervised home-based training. A detailed description of the study design has been previously published13 and the study protocol can be found in Supplement 1. The study was approved by the local ethics committees for medical research at all participating sites. All participants provided written informed consent.

Patients

Sedentary patients with signs and symptoms of HFpEF (exertional dyspnea [New York Heart Association class II-III], LVEF of 50% or greater, and elevated estimated LV filling pressure [E/e′ medial ≥15] or E/e′ medial of 8 or greater with concurrent elevated natriuretic peptides [NT-proBNP ≥220 pg/mL or BNP ≥80 pg/mL])14 were eligible to participate in the trial.

Randomization

A web-based system was used to assign patients in a 1:1:1 ratio to high-intensity interval training, moderate continuous training, or guideline control. Randomization was stratified by study site using block sizes of 12 (first block) and 6 (following blocks).

Intervention

High-intensity interval training was scheduled 3 times per week for 38 minutes per session (10-minute warm-up at 35%-50% of heart rate reserve, 4 × 4-minute intervals at 80%-90% of heart rate reserve, interspaced by 3 minutes of active recovery), while moderate continuous training was scheduled 5 times per week for 40 minutes per session (35%-50% of heart rate reserve). Patients assigned to guideline control received 1-time advice on physical activity according to guidelines.15

Individual exercise intensity was determined by a maximal cardiopulmonary exercise test at baseline and was adapted after 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months of exercise training based on repeated cardiopulmonary exercise tests. In contrast to the initial study design13 (exercise intensity based on the percentage of maximum heart rate), we applied percentage of heart rate reserve because of known high prevalence of chronotropic incompetence in patients with HFpEF. In patients with atrial fibrillation, a constant workload was determined based on Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion Scale scores 15-17 (high-intensity intervals) or 11-13 (moderate continuous training).

From months 1 through 3, supervised training was offered thrice per week. Patients in the moderate continuous training group additionally performed 2 home-based sessions per week on stationary cycle ergometers. From months 4 through 12, training sessions were continued at home with the same exercise protocol as performed during the in-clinic phase. Training intensities were documented via telemonitoring with a heart rate sensor (Polar H7, Polar Electro GmbH) and connected to a mobile phone (iPhone 4S, Apple Inc) and a telemedicine database (vitaphone GmbH part of vitagroup AG) to enable immediate feedback to patients. In case of a decline in attendance to less than 70% of scheduled exercise sessions or a decline in exercise intensity during sessions, patients were encouraged by telephone contact to increase adherence to meet study targets.

Clinical Assessments

All patients were assessed at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months after randomization. Examinations were performed according to standard operating procedures and included medical history, physical examination, anthropometry, electrocardiogram, blood analysis, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, echocardiography, and the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ). The staff members conducting the evaluations were not blinded to treatment groups.

Cardiopulmonary exercise testing was performed according to current recommendations16 and analyzed in a blinded manner at the study core laboratory in Munich. Peak V̇o2 was defined as the highest 30-second average within the last minute of exercise.17 The first ventilatory threshold (VT1) was set by the V-slope method18 and the minute ventilation to carbon dioxide production slope (V̇E/V̇co2 slope) was calculated using the entire exercise data.

Echocardiography was performed by experienced and instructed sonographers. Study inclusion was based on on-site measures of LVEF and E/e′ medial. All echocardiograhic analyses were performed centrally by the Academic Echocardiography Core Lab at Charité Berlin, blinded to treatment group assignment. Local NT-proBNP values were used for study inclusion; all NT-proBNP values reported were analyzed by a central core laboratory (Clinical Institute of Medical and Chemical Laboratory Diagnostics, Medical University of Graz, Austria).

Outcomes

The primary end point was the change in peak V̇o2 after 3 months. Secondary end points included changes from baseline to 3 and 12 months for echocardiographic measures of diastolic function (E/e' medial, e' medial, left atrial volume index), NT-proBNP, cardiopulmonary exercise testing parameters (peak V̇o2, V̇E/V̇co2 slope, submaximal workload at VT1), and the health-related QoL domain of the KCCQ (score range: 0-100, higher scores reflect better QoL; minimal clinically important difference: 5 points19). The additional secondary end points of changes in flow-mediated dilatation from baseline to 3 and 12 months were obtained only in a subgroup of patients and are not reported here. Adverse events and serious adverse events were documented and categorized in each study site and then evaluated by an independent safety committee.

Statistics

The trial protocol defined 2.5 mL/kg/min as the smallest V̇o2 effect that would be important to detect, stating that any smaller effect would not be of clinical or substantive importance. Based on this and on the findings of a pilot study,20 a mean (SD) difference in change of peak V̇o2 of 2.5 (3.5) mL/kg/min between moderate continuous training and guideline control was assumed. By assuming an additional mean (SD) difference of 2.5 (3.5) mL/kg/min between high-intensity interval training and moderate continuous training, a power of at least 90% for pairwise group comparisons was able to be obtained with a sample size of 45 patients per group (α = 5%). As a moderate number of missing values was expected and due to the multicenter design, a total number of 180 patients (60 per group) was intended to be included in the study.

For analysis of the primary end point, analysis of variance was prespecified in a first step to compare means of all groups using a significance level of α = 5%. Performance of pairwise mean comparisons with t tests for independent samples were planned, only if the global null hypothesis of all group means being equal could be rejected (α = 5%, 2-sided, closed testing principle). All patients were analyzed according to their randomization group. To account for missing values in the primary end point variable (peak V̇o2 at 3 months), a prespecified multiple imputation approach was performed (for details, see eMethods in Supplement 2). In a sensitivity analysis, only patients with complete paired baseline and 3-month follow-up peak V̇o2 measures were included.

For all secondary end points, analysis of variance was performed to compare mean changes between all 3 study groups considering all available data, and 95% CIs for differences in mean changes between groups are presented. CIs have not been adjusted for multiplicity; therefore, analyses of secondary end points should be interpreted as exploratory. The analysis of the primary end point was repeated within prespecified subgroups (center, sex, body mass index [BMI, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared], age, baseline E/e′, and baseline peak V̇o2) considering complete cases only, and tests for interaction between these variables and study group were performed by fitting corresponding linear regression models to the data. Furthermore, we performed a per-protocol analysis including only patients with adherence of 70% or greater to the scheduled exercise sessions. All statistical analyses were performed using R Statistical Software (Version 3.6.0; Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

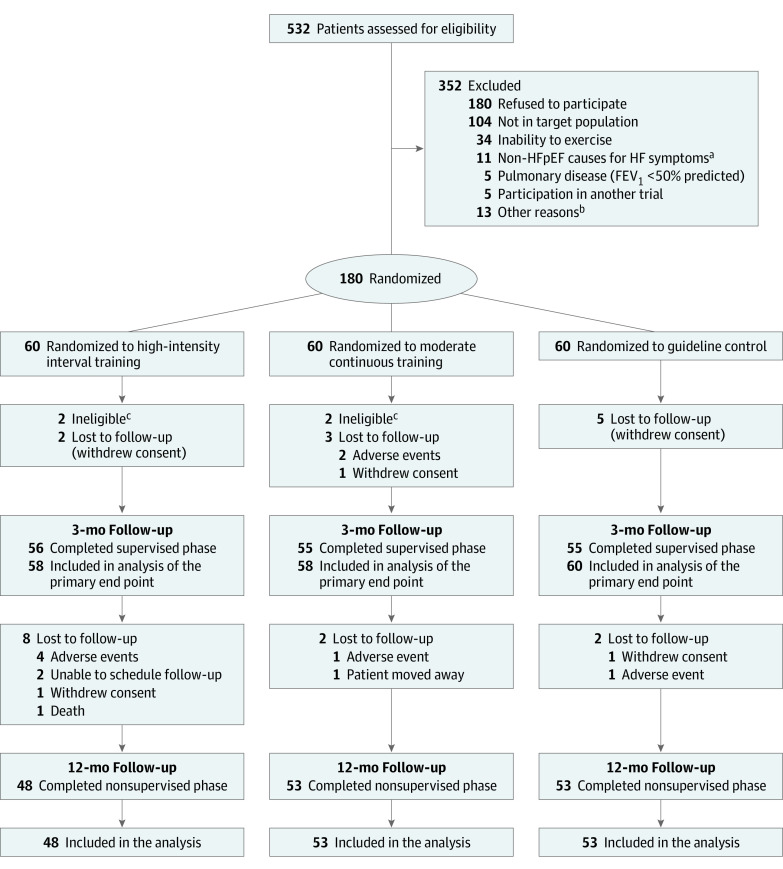

Inclusion of patients started in July 2014 and the last patient completed the trial in September 2018. From 532 screenings, 180 patients were enrolled in the trial. Four participants not meeting HFpEF criteria14 (eTable 1 in Supplement 2) were excluded from analysis after blinded review of eligibility for all participants based on their status before randomization.21 Ten patients were lost to follow-up at 3 months, and an additional 12 lost to follow-up at 12 months (Figure 1). We recruited a typical HFpEF population of elderly, predominantly female patients with overweight/obesity with a typical risk and comorbidity background. Baseline patient demographic and clinical characteristics (mean age, 70 years; 120 women [67%]; mean BMI, 30.0; mean E/e′ medial, 15.8; mean NT-proBNP, 671 pg/mL; mean peak V̇o2, 18.8 mL/kg/min) are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1. Patient Recruitment, Randomization, and Follow-up in the OptimEx-Clin Study.

FEV1 indicates forced expiratory volume in first second of expiration; HF, heart failure; and HFpEF, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.

aNon-HFpEF causes for HF symptoms included significant valvular disease, coronary disease, uncontrolled hypertension or arrhythmia, or primary cardiomyopathies.

bThe other reasons were signs of ischemia during cardiopulmonary exercise testing (n = 3), comorbidities that may influence 1-year prognosis (n = 3), upcoming planned surgery (n = 2), social reasons (n = 2), concerns about patient’s ability to adhere and compliance (n = 1), recurrent syncopes (n = 1), and planned travel (n = 1).

cRemoved after blinded review of eligibility of all patients.

Table 1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics at Baseline.

| Characteristic | No. (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| High-intensity interval training (n = 58)a | Moderate continuous training (n = 58)a | Guideline control (n = 60)a | |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 41 (71) | 35 (60) | 41 (68) |

| Male | 17 (29) | 23 (40) | 19 (32) |

| Age at inclusion, mean (SD), y | 70 (7) | 70 (8) | 69 (10) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD)b | 30.0 (5.7) | 31.1 (6.2) | 29.0 (4.7) |

| Resting heart rate, mean (SD), beats/min | 65 (12) | 65 (10) | 65 (11) |

| Blood pressure, mean (SD), mm Hg | |||

| Systolic | 127 (14) | 131 (13) | 127 (14) |

| Diastolic | 74(11) | 75 (10) | 74 (10) |

| New York Heart Association classc | |||

| II: mild symptoms | 44 (76) | 44 (76) | 42 (70) |

| III: marked symptoms | 14 (24) | 14 (24) | 18 (30) |

| Cardiovascular risk factors | |||

| Hypertension | 50 (86) | 49 (84) | 51 (85) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 38 (66) | 40 (69) | 45 (75) |

| Diabetes | 16 (28) | 16 (28) | 14 (23) |

| Smoking | |||

| No (never smoked) | 30 (52) | 32 (55) | 35 (58) |

| Ex-smoker | 25 (43) | 23 (40) | 23 (38) |

| Current | 3 (5) | 3 (5) | 2 (3) |

| Cardiovascular disease | |||

| Coronary artery disease | 15 (26) | 18 (31) | 17 (28) |

| Atrial fibrillation | |||

| Paroxysmal | 10 (17) | 5 (9) | 8 (14) |

| Persistent | 4 (7) | 6 (10) | 3 (5) |

| Permanent | 6 (10) | 5 (8) | 2 (3) |

| Sleep apnea syndrome | 11 (19) | 11 (19) | 11 (18) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 3 (5) | 4 (7) | 2 (3) |

| Heart failure medication | |||

| β-Blockers | 40 (69) | 34 (59) | 40 (67) |

| Thiazide/loop diuretics | 36 (62) | 30 (52) | 34 (57) |

| Angiotensin receptor blocker | 25 (43) | 26 (45) | 24 (40) |

| Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor | 19 (33) | 18 (31) | 17 (28) |

| Aldosterone antagonists | 8 (14) | 6 (10) | 5 (8) |

| Echocardiography, mean (SD) [No.] | |||

| E/e′ medial | 15.8 (3.7) [57] | 15.9 (4.1) [58] | 15.7 (5.6) [57] |

| e′ medial, cm/s | 6.2 (1.8) [57] | 6.1 (1.6) [58] | 6.3 (1.8) [57] |

| Left atrial volume index, mL/m2 | 35.4 (9.0) [39] | 37.9 (13.0) [42] | 39.8 (13.5) [48] |

| E/A | 1.3 (0.8) [47] | 1.1 (0.4) [48] | 1.1 (0.6) [54] |

| Others | |||

| NT-proBNP | |||

| Mean (SD), pg/mL [No.] | 475 (522) [57] | 656 (806) [55] | 875 (1950) [59] |

| Median (IQR), pg/mL [No.] | 281 (130-654) [57] | 414 (199-751) [55] | 321 (171-578) [59] |

| KCCQ QoL domain, mean (SD) [No.]d | 68.0 (24.2) [58] | 62.2 (26.2) [56] | 65.7 (20.4) [58] |

Abbreviations: A, peak velocity flow in late diastole caused by atrial contraction; E, peak velocity blood flow from ventricular relaxation in early diastole; e′, mitral annular early diastolic velocity; IQR, interquartile range; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; NT-proBNP, N-terminal pro–hormone of brain natriuretic peptide; QoL, quality of life.

Data are presented as absolute (relative) frequency, mean (SD) or median (IQR). Data for echocardiography, NT-proBNP and KCCQ have been analyzed at the corresponding core labs.

Calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

New York Heart Association functional class quantifies the severity of functional limitation. Class I indicates no limiting symptoms with ordinary activity; class II, mild symptoms with ordinary activity; class III, marked symptoms with ordinary activity; and class IV, severe symptoms during ordinary activity with symptoms even at rest.

Higher scores indicate better QoL (score range, 0-100, minimal clinically important difference, 5 points).

Primary Outcome

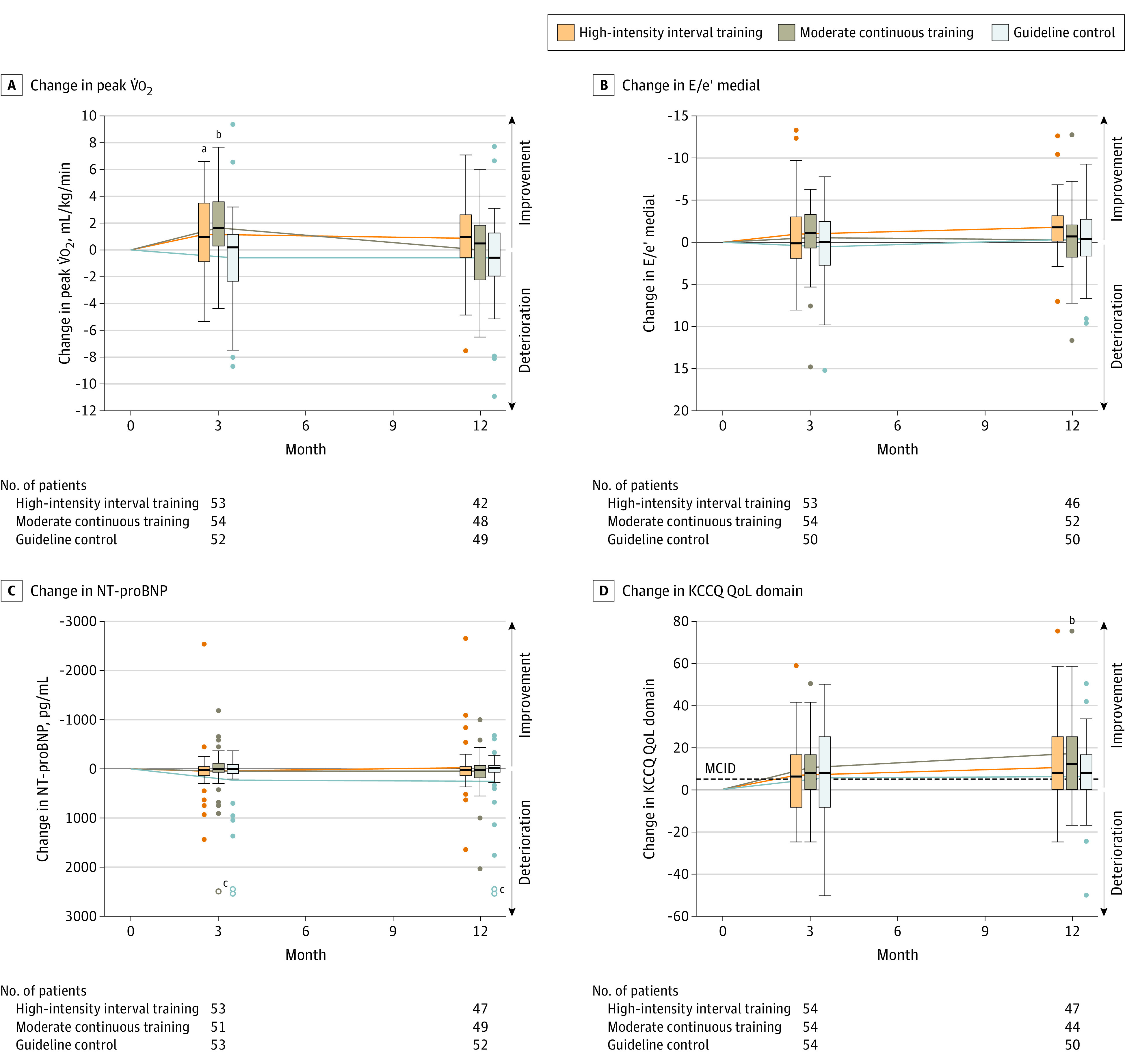

After 3 months of intervention, change in peak V̇o2 differed significantly between the groups (mean [SD] for high-intensity interval training: 1.1 [3.0] mL/kg/min; moderate continuous training: 1.6 [2.5] mL/kg/min; guideline control: −0.6 [3.3] mL/kg/min; P = .002). Pairwise comparisons showed significantly higher changes in high-intensity interval training vs guideline control (difference in mean changes: 1.5 mL/kg/min [95% CI, 0.4 to 2.7], P = .01) and moderate continuous training vs guideline control (2.0 mL/kg/min [95% CI, 0.9 to 3.1], P = .001) with no significant difference between high-intensity interval training and moderate continuous training (−0.4 mL/kg/min [95% CI, −1.4 to 0.6], P = .41) (Figure 2A, Table 2). Subgroup analysis for change in peak V̇o2 after 3 months did not show any significant interactions of relevant characteristics with study group (eFigure 1 and eTable 2 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Changes in Peak Oxygen Consumption (V̇o2), Estimated Left Ventricular Filling Pressure (E/e′ Medial), N-Terminal Pro–Brain Natriuretic Peptide (NT-proBNP), and Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ) Quality of Life (QoL) at 3 and 12 Months.

Changes are calculated from baseline to 3 and 12 months of intervention within each group (solid lines connect the mean changes from baseline to 3 months and baseline to 12 months). In the KCCQ, higher scores indicate better QoL (score range, 0-100; minimal clinically important difference [MCID, dashed line], 5 points).

aSignificant difference (P < .05) in change between high-intensity interval training and guideline control.

bSignificant difference (P < .05) in change between moderate continuous training and guideline control.

cOpen points are at 3586 pg/mL (moderate continuous training, change to 3 months), 4133 and 5783 pg/mL (guideline control, change to 3 months), 4134 and 7063 pg/mL (guideline control, change to 12 months).

Table 2. Primary and Secondary End Points After 3 Months.

| Mean (SD) [sample size] | Difference (95% CI) [sample size] | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIIT | MCT | Guideline control | ||||||||||

| Baseline | 3 mo | Difference | Baseline | 3 mo | Difference | Baseline | 3 mo | Difference | HIIT vs guideline control | MCT vs guideline control | HIIT vs MCT | |

| Primary outcome | ||||||||||||

| Peak V̇o2, mL/kg/min | 18.9 (5.4) [58] | 20.2 (6.0) [53] | 1.1 (3.0) [53] | 18.2 (5.1) [58] | 19.8 (5.8) [54] | 1.6 (2.5) [54] | 19.4 (5.6) [60] | 18.9 (5.7) [52] | −0.6 (3.3) [52] | 1.5 (0.4 to 2.7) [118]a | 2.0 (0.9 to 3.1) [118]a | −0.4 (−1.4 to 0.6) [116]a |

| 1.8 (0.5 to 3.0) [105]b | 2.3 (1.1 to 3.4) [106]b | −0.5 (−1.5 to 0.6) [107]b | ||||||||||

| Secondary outcomes | ||||||||||||

| V̇E/V̇co2 slope | 34.5 (7.9) [58] | 35.0 (9.8) [53] | 0.7 (4.4) [53] | 34.2 (7.2) [58] | 33.7 (6.8) [54] | −0.7 (4.4) [54] | 33.2 (5.9) [59] | 32.6 (5.3) [51] | −1.0 (5.4) [51] | 1.7 (−0.2 to 3.6) [104] | 0.2 (−1.7 to 2.2) [105] | 1.5 (−0.3 to 3.2) [107] |

| Workload at VT1, W | 45 (17) [58] | 49 (18) [53] | 4 (12) [53] | 46 (21) [57] | 53 (25) [53] | 8 (13) [52] | 45 (15) [58] | 47 (16) [50] | 1 (10) [50] | 3 (−2 to 7) [103] | 6 (2 to 11) [102] | −4 (−9 to 1) [105] |

| E/e' medial | 15.8 (3.7) [57] | 15.2 (4.8) [54] | −0.9 (4.5) [53] | 15.9 (4.1) [58] | 15.6 (5.0) [54] | −0.5 (3.7) [54] | 15.7 (5.6) [57] | 16.5 (7.2) [53] | 0.6 (4.6) [50] | −1.5 (−3.2 to 0.3) [103] | −1.1 (−2.7 to 0.5) [104] | −0.4 (−1.9 to 1.2) [107] |

| e' medial, cm/s | 6.2 (1.8) [57] | 6.23 (1.72) [54] | 0.0 (1.7) [53] | 6.1 (1.6) [58] | 5.95 (1.65) [54] | −0.1 (1.3) [54] | 6.3 (1.8) [57] | 5.95 (1.84) [53] | −0.3 (1.5) [50] | 0.3 (−0.3 to 1.0) [103] | 0.2 (−0.3 to 0.8) [104] | 0.1 (−0.5 to 0.7) [107] |

| LAVI, mL/m2 | 35.4 (9.0) [39] | 35.2 (10.2) [34] | −0.4 (4.0) [26] | 37.9 (13.0) [42] | 36.8 (10.5) [28] | 0.5 (4.1) [25] | 39.8 (13.5) [48] | 38.4 (14.7) [40] | −0.7 (4.0) [35] | 0.3 (−1.7 to 2.4) [61] | 1.2 (−0.9 to 3.4) [60] | −0.9 (−3.2 to 1.4) [51] |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 475 (522) [57] | 520 (646) [53] | 25 (469) [53] | 656 (806) [55] | 695 (1212) [53] | 43 (598) [53] | 875 (1950) [59] | 1164 (2871) [53] | 226 (1010) [53] | −201 (−505 to 104) [106] | −183 (−505 to 139) [106] | −18 (−228 to 192) [106] |

| KCCQ QoL domainc | 68 (24) [58] | 73 (26) [54] | 7 (21) [54] | 62 (26) [56] | 72 (21) [55] | 10 (17) [54] | 66 (20) [58] | 72 (23) [55] | 6 (21) [54] | 1.0 (−7.2 to 9.2) [108] | 4.8 (−2.6 to 12.2) [108] | −3.8 (−11.2 to 3.6) [108] |

Abbreviations: E, peak velocity blood flow from ventricular relaxation in early diastole; e’, mitral annular early diastolic velocity; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LAVI, left atrial volume index; MCT, moderate continuous training; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; QoL, quality of life; V̇E/V̇co2 slope, minute ventilation to carbon dioxide output slope; V̇o2, oxygen consumption; VT1, ventilatory threshold.

Results of the primary analysis using a prespecified multiple imputation approach for missing values.

Results of the complete case analysis for the primary end point considering all available data (without imputation).

Higher scores indicate better QoL (score range, 0-100; minimal clinically important difference, 5 points).

Secondary Outcomes

After 12 months, the change in peak V̇o2 (Figure 2A, Table 3) was not significantly different between the groups (mean [SD] for high-intensity interval training: 0.9 [3.0] mL/kg/min, moderate continuous training: 0 [3.1] mL/kg/min, guideline control: −0.6 [3.4] mL/kg/min, P = .11). The change in workload at VT1 after 3 months (Table 2) was significantly higher in the moderate continuous training group compared with the guideline control group (6 W [95% CI, 2 to 11]) without significant differences between high-intensity interval training and guideline control (3 W [95% CI, −2 to 7]) and between high-intensity interval training and moderate continuous training (−4 W [95% CI, −9 to 1]). No significant differences between groups were observed after 12 months (Table 3). Change in V̇E/V̇co2 slope after 3 months was not significantly different between groups (Table 2). There were no significant differences for changes in any echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function between the groups (Figure 2B, Tables 2 and 3). Moreover, the change in NT-proBNP did not significantly differ between the groups (Figure 2C, Tables 2 and 3). Changes in the QoL domain of the KCCQ did not significantly differ between groups after 3 months of exercise intervention (Figure 2D, Table 2). However, after 12 months, the change in the QoL domain was significantly higher in moderate continuous training compared with guideline control (11 [95% CI, 2 to 19]) without significant differences between high-intensity interval training and guideline control (4 [95% CI, −3 to 12]) or high-intensity interval training and moderate continuous training (−6 [95% CI, −15 to 2]; Figure 2D, Table 3). Additional data for cardiopulmonary exercise testing, echocardiography, and KCCQ are provided in eTables 3, 4, and 5, respectively, in Supplement 2.

Table 3. Group Differences in Exploratory End Points After 12 Months.

| Secondary outcome | Mean (SD) [sample size] | Difference (95% CI) [sample size] | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIIT | MCT | Guideline control | HIIT vs guideline control | MCT vs guideline control | HIIT vs MCT | |||||||

| Baseline | 12 mo | Difference | Baseline | 12 mo | Difference | Baseline | 12 mo | Difference | ||||

| Peak V̇o2, mL/kg/min | 18.9 (5.4) [58] | 19.9 (6.1) [42] | 0.9 (3.0) [42] | 18.2 (5.1) [58] | 18.1 (5.9) [48] | 0 (3.1) [48] | 19.4 (5.6) [60] | 19.5 (5.1) [49] | −0.6 (3.4) [49] | 1.4 (0.1 to 2.8) [91] | 0.6 (−0.7 to 1.9) [97] | 0.8 (−0.5 to 2.1) [90] |

| V̇E/V̇co2 slope | 34.5 (7.9) [58] | 36.6 (8.4) [42] | 2.0 (5.1) [42] | 34.2 (7.2) [58] | 33.9 (7.1) [48] | −0.7 (4.6) [48] | 33.2 (5.9) [59] | 34.3 (7.4) [49] | 1.1 (4.9) [49] | 0.9 (−1.2 to 3.0) [91] | −1.9 (−3.8 to 0.0) [97] | 2.8 (0.7 to 4.8) [90] |

| Workload at VT1, W | 45 (17) [58] | 46 (17) [41] | 1 (12) [41] | 46 (21) [57] | 45 (21) [47] | −1 (12) [46] | 45 (15) [58] | 43 (14) [49] | −3 (11) [49] | 4 (−1 to 9) [90] | 3 (−2 to 7) [95] | 2 (−4 to 7) [87] |

| E/e' medial | 15.8 (3.7) [57] | 14.2 (3.9) [47] | −1.8 (3.3) [46] | 15.9 (4.1) [58] | 15.6 (4.4) [52] | −0.3 (4.2) [52] | 15.7 (5.6) [57] | 15.7 (5.5) [52] | −0.4 (4.0) [50] | −1.4 (−2.9 to 0.1) [96] | 0.1 (−1.5 to 1.7) [102] | −1.5 (−3.0 to 0.0) [98] |

| e' medial, cm/s | 6.2 (1.8) [57] | 6.2 (1.7) [47] | 0.1 (1.5) [46] | 6.1 (1.6) [58] | 5.9 (1.5) [52] | −0.2 (1.1) [52] | 6.3 (1.8) [57] | 6.1 (1.7) [52] | −0.2 (1.5) [50] | 0.3 (−0.3 to 0.9) [96] | 0.0 (−0.5 to 0.5) [102] | 0.3 (−0.2 to 0.9) [98] |

| LAVI, mL/m2 | 35.4 (9.0) [39] | 37.4 (10.9) [26] | 0.7 (5.8) [21] | 37.9 (13.0) [42] | 36.6 (9.2) [23] | 1.2 (3.8) [20] | 39.8 (13.5) [48] | 39.2 (1.8) [38] | 0.3 (5.2) [33] | 0.4 (−2.7 to 3.5) [54] | 0.9 (−1.6 to 3.3) [53] | −0.5 (−3.5 to 2.6) [41] |

| NT-proBNP, pg/mL | 475 (522) [57] | 471 (468) [47] | −24 (539) [47] | 656 (806) [55] | 698 (1026) [52] | 42 (422) [49] | 875 (1950) [59] | 1037 (1026) [52] | 237 (1177) [52] | −261 (−622 to 100) [99] | −195 (−543 to 152) [101] | −66 (−263 to 131) [96] |

| KCCQ QoL domaina | 68 (24) [58] | 80 (21) [47] | 11 (20) [47] | 62 (26) [56] | 77 (19) [45] | 17 (21) [44] | 66 (20) [58] | 72 (24) [51] | 6 (18) [50] | 4 (−3 to 12) [97] | 11 (2 to 19) [94] | −6 (−15 to 2) [91] |

Abbreviations: E, peak velocity blood flow from ventricular relaxation in early diastole; e′, mitral annular early diastolic velocity; HIIT, high-intensity interval training; KCCQ, Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire; LAVI, left atrial volume index; MCT, moderate continuous training; NT-proBNP, N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide; QoL, quality of life; V̇o2, oxygen consumption; V̇E/V̇co2 slope, minute ventilation to carbon dioxide output slope; VT1, ventilatory threshold.

Higher scores indicate better QoL (score range, 0-100; minimal clinically important difference, 5 points).

Adherence and Per-Protocol Analysis

Of those patients completing the 3-month follow-up (56 in the high-intensity interval training group, 55 in the moderate continuous training group; Figure 1), 45 (80.4%) doing high-intensity interval training and 42 (76.4%) doing moderate continuous training performed at least 70% of exercise sessions. Patients randomized to high-intensity interval training performed a median of 2.5 sessions (interquartile range [IQR], 2.1-2.8) or 96 minutes (IQR, 82-105) per week, while patients randomized to moderate continuous training performed 4.4 sessions (IQR, 3.4-4.7) or 176 minutes (IQR, 137-188) per week. During the home-based phase (months 4-12), adherence dropped to 2.0 sessions (IQR, 1.2-2.4) or 77 minutes (IQR, 46 - 92) per week in the high-intensity interval training group and 3.6 sessions (IQR, 2.7-4.3) or 144 minutes (IQR, 108-171) per week in the moderate continuous training group. Of the 48 high-intensity interval training and 53 moderate continuous training patients who completed the full training program (12 months, see Figure 1), 27 (56.3%) and 32 (60.4%) patients performed at least 70% of exercise sessions, respectively (eFigure 2 and eTable 6 in Supplement 2). Drop offs in adherence to less than 70% of scheduled exercise sessions were mainly due to clinical reasons (n = 60) and personal reasons such as vacation (n = 20), motivational problems (n = 12), and trouble with the ergometer or telemedical device (n = 2) (multiple responses possible). Results of the per-protocol analysis were similar to the main results of the trial (eTable 7 in Supplement 2).

Adverse Events

There were adverse events in 102 patients (58%) (high-intensity interval training: 36 patients [62%], moderate continuous training: 39 patients [67%], guideline control: 27 patients [45%]). Moreover, 52 patients (30%) experienced events that were classified as serious adverse events (high-intensity interval training: 18 patients [31%], moderate continuous training: 18 patients [31%], guideline control: 16 patients [27%]). Acute coronary syndrome was the most common cardiovascular adverse event (high-intensity interval training: 4 patients [7%], moderate continuous training: 3 patients [5%], guideline control: 5 patients [8%]). Worsening heart failure occurred in 3 patients (5%) of each group. Atrial fibrillation was observed in 4 (7%), 3 (5%), and 2 (3%) patients randomized to high-intensity interval training, moderate continuous training, and guideline control, respectively (eTable 8 in Supplement 2). There was 1 cardiac death in the high-intensity interval training group (unrelated to exercise) and 6 events that occurred during (moderate continuous training: atrial fibrillation, syncope, back pain; high-intensity interval training: compression of the coccyx due to a fall while alighting the bicycle ergometer, muscle weakness) or within 2 hours after exercise training (high-intensity interval training: occlusion of peripheral bypass). An overview of adverse events and serious adverse events is provided in eTables 8 and 9 in Supplement 2.

Discussion

Among patients with HFpEF, changes in peak V̇o2 were not significantly different at 3 or 12 months between those assigned to high-intensity interval training vs moderate continuous training. Furthermore, neither group met the a priori–defined minimal clinically important difference of 2.5 mL/kg/min compared with the guideline control at any time point.

Changes in peak V̇o2 after 3 months were similar to those reported in a recent meta-analysis7 of 8 smaller studies (n = 436 patients with HFpEF, 12-24 weeks, 1.7 mL/kg/min for exercise training vs control). However, the present trial could not confirm the findings of 2 smaller single-center studies in HFpEF showing superiority of high-intensity interval training over moderate continuous training.9,10 While in the study by Angadi et al9 (n = 15, 4 weeks’ duration), the exercise volume for moderate continuous training (3 × 30 minutes/week) might have been too low, patients included in the trial by Donelli da Silveira et al10 (n = 19, 12 weeks’ duration) were relatively young (mean age, 60 years) with few comorbidities.

In accordance with most of the previous exercise trials in HFpEF,7,11 the present study failed to demonstrate that the improvement in exercise capacity at 3 months was related to changes in diastolic function. These findings underscore that apart from diastolic dysfunction, other mechanisms likely contributed to the observed improvement in peak V̇o2.22,23 In HFpEF, peripheral vascular function and skeletal muscle function are disturbed, and exercise training can partially reverse these changes.24,25,26 QoL improved by more than 5 points in all groups including guideline control (from baseline to 3 and 12 months), which can be interpreted as clinically relevant19 and is in line with previous exercise trials in HFpEF and HF with reduced EF.27,28 At 12 months, the difference in change in QoL between moderate continuous training and guideline control was statistically significant; however, this has to be interpreted as an exploratory finding.

Adherence to exercise protocols is a major concern in long-term exercise intervention studies. In the present trial, despite telemedical support, which proved to have high acceptance even in the group of elderly individuals, only about one-half of the patients performed at least 70% of the prescribed training sessions during home-based exercise training (months 4-12). Even though the median amount of exercise per week was in line with current guideline recommendations15,29 and for the moderate continuous training group almost twice as high as in the HF-ACTION study,30 the adherence rate might have still been too low to induce significant long-term effects of exercise training.

The number of adverse and serious adverse events was considerably higher compared with previous exercise trials in HFpEF20,27,31,32,33,34 and reflects the multimorbid condition of the patients included in the present trial. The higher number of nonserious, noncardiovascular adverse events in the training groups may be explained by the more frequent contacts and therefore higher reporting in these groups (eg, number of respiratory tract infections and knee/hip pain, eTable 8 in Supplement 2).

Comparing the current trial with the so far largest exercise trial in HFpEF assessing 100 patients,27 patients in the present trial were slightly older (mean age, 70 vs 67 years), less obese (mean BMI, 30.0 vs 39.3), with more severe diastolic dysfunction (mean E/e′, 15.8 vs 13.1), and comparable absolute values for peak V̇o2 (1530 vs 1515 mL/kg/min overall). In addition, patient characteristics are also comparable with pharmacological studies in HFpEF such as the ALDO-DHF trial (mean age, 67 years; peak V̇o2, 16.4 mL/kg/min; E/e′, 12.8)35 or the PARAGON trial (mean age, 73 years; BMI, 30.3).36

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the staff conducting the evaluations was not blinded to the treatment group assignment, which could have had an effect on the maximal exhaustion during cardiopulmonary exercise testing. However, the respiratory exchange ratio at peak exercise did not significantly differ between groups and time points (eTable 3 in Supplement 2). Second, the lack of exercise echocardiography, assessing changes of diastolic function during exercise, limits the interpretation of the effects of exercise training on cardiac function. Third, the attenuation in adherence limits the interpretation of long-term effects and underscores the need for more effective ways to improve long-term adherence.37 Fourth, multiplicity of analyses limits the interpretability of the secondary outcomes.

Conclusions

Among patients with HFpEF, there was no statistically significant difference in change in peak V̇o2 at 3 months between those assigned to high-intensity interval vs moderate continuous training, and neither group met the prespecified minimal clinically important difference compared with the guideline control. These findings do not support either high-intensity interval training or moderate continuous training compared with guideline-based physical activity for patients with HFpEF.

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Group Members

eMethods. Description of Multiple Imputation Approach

eFigure 1. Subgroup Analysis of the Primary Endpoint (Change in Peak V̇O2 After 3 Months)

eFigure 2. Relative Frequency of Performed Exercise Training Sessions Within 3-Month and 12-Month Intervention Period in High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) and Moderate Continuous Training (MCT)

eTable 1. Ineligible Participants Not Meeting HFpEF Criteria Who Were Inadvertently Randomized and Excluded From the Analysis

eTable 2. Subgroup Analysis of the Primary Endpoint (Change in Peak V̇O2 After 3 Months)

eTable 3. Results From Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eTable 4. Results from echocardiography for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eTable 5. Results From Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eTable 6. Exercise Training Data and Adherence to the Prescribed Exercise Intervention for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) and Moderate Continuous Training (MCT)

eTable 7. Group Differences in Primary and Secondary Endpoints After 3 and 12 Months Including Only the Per-Protocol Population of Patients Who Performed at Least 70% of the Scheduled Training Sessions

eTable 8. List of Cardiovascular and the Most Common Non-cardiovascular Adverse Events for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eTable 9. List of Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Virani SS, Alonso A, Benjamin EJ, et al. ; American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee . Heart disease and stroke statistics. Circulation. 2020;141(9):e139-e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ho JE, Enserro D, Brouwers FP, et al. . Predicting heart failure with preserved and reduced ejection fraction: the International Collaboration on Heart Failure Subtypes. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(6):e003116. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.003116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chang PP, Chambless LE, Shahar E, et al. . Incidence and survival of hospitalized acute decompensated heart failure in four US communities (from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study). Am J Cardiol. 2014;113(3):504-510. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.10.032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pandey A, LaMonte M, Klein L, et al. . Relationship between physical activity, body mass index, and risk of heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(9):1129-1142. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kitzman DW, Little WC, Brubaker PH, et al. . Pathophysiological characterization of isolated diastolic heart failure in comparison to systolic heart failure. JAMA. 2002;288(17):2144-2150. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.17.2144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bonsu KO, Arunmanakul P, Chaiyakunapruk N. Pharmacological treatments for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Rev. 2018;23(2):147-156. doi: 10.1007/s10741-018-9679-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuta H, Goto T, Wakami K, Kamiya T, Ohte N. Effects of exercise training on cardiac function, exercise capacity, and quality of life in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Heart Fail Rev. 2019;24(4):535-547. doi: 10.1007/s10741-019-09774-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haykowsky MJ, Brubaker PH, Stewart KP, Morgan TM, Eggebeen J, Kitzman DW. Effect of endurance training on the determinants of peak exercise oxygen consumption in elderly patients with stable compensated heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(2):120-128. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.02.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angadi SS, Mookadam F, Lee CD, Tucker WJ, Haykowsky MJ, Gaesser GA. High-intensity interval training vs. moderate-intensity continuous exercise training in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a pilot study. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2015;119(6):753-758. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00518.2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Donelli da Silveira A, Beust de Lima J, da Silva Piardi D, et al. . High-intensity interval training is effective and superior to moderate continuous training in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2020;27(16):1733-1743. doi: 10.1177/2047487319901206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujimoto N, Prasad A, Hastings JL, et al. . Cardiovascular effects of 1 year of progressive endurance exercise training in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Am Heart J. 2012;164(6):869-877. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.06.028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bobenko A, Bartels I, Münch M, et al. . Amount or intensity? potential targets of exercise interventions in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. ESC Heart Fail. 2018;5(1):53-62. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suchy C, Massen L, Rognmo O, et al. . Optimising exercise training in prevention and treatment of diastolic heart failure (OptimEx-CLIN). Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(2)(suppl):18-25. doi: 10.1177/2047487314552764 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paulus WJ, Tschöpe C, Sanderson JE, et al. . How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: a consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(20):2539-2550. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Piepoli MF, Hoes AW, Agewall S, et al. ; ESC Scientific Document Group . 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: the Sixth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and Other Societies on Cardiovascular Disease Prevention in Clinical Practice (constituted by representatives of 10 societies and by invited experts) developed with the special contribution of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation (EACPR). Eur Heart J. 2016;37(29):2315-2381. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guazzi M, Arena R, Halle M, Piepoli MF, Myers J, Lavie CJ. 2016 Focused update: clinical recommendations for cardiopulmonary exercise testing data assessment in specific patient populations. Circulation. 2016;133(24):e694-e711. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mezzani A, Agostoni P, Cohen-Solal A, et al. . Standards for the use of cardiopulmonary exercise testing for the functional evaluation of cardiac patients: a report from the Exercise Physiology Section of the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2009;16(3):249-267. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e32832914c8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaver WL, Wasserman K, Whipp BJ. A new method for detecting anaerobic threshold by gas exchange. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1986;60(6):2020-2027. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1986.60.6.2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spertus J, Peterson E, Conard MW, et al. ; Cardiovascular Outcomes Research Consortium . Monitoring clinical changes in patients with heart failure: a comparison of methods. Am Heart J. 2005;150(4):707-715. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2004.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edelmann F, Gelbrich G, Düngen HD, et al. . Exercise training improves exercise capacity and diastolic function in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: results of the Ex-DHF (Exercise Training in Diastolic Heart Failure) pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58(17):1780-1791. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.06.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yelland LN, Sullivan TR, Voysey M, Lee KJ, Cook JA, Forbes AB. Applying the intention-to-treat principle in practice. Clin Trials. 2015;12(4):418-423. doi: 10.1177/1740774515588097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tucker WJ, Lijauco CC, Hearon CM Jr, et al. . Mechanisms of the improvement in peak VO2 with exercise training in heart failure with reduced or preserved ejection fraction. Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(1):9-21. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2017.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tucker WJ, Nelson MD, Beaudry RI, et al. . Impact of exercise training on peak oxygen uptake and its determinants in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Card Fail Rev. 2016;2(2):95-101. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2016:16:2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gevaert AB, Beckers PJ, Van Craenenbroeck AH, et al. . Endothelial dysfunction and cellular repair in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2019;21(1):125-127. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmederer Z, Rolim N, Bowen TS, Linke A, Wisloff U, Adams V; OptimEx study group . Endothelial function is disturbed in a hypertensive diabetic animal model of HFpEF. Int J Cardiol. 2018;273:147-154. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.08.087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bowen TS, Rolim NP, Fischer T, et al. ; Optimex Study Group . Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction induces molecular, mitochondrial, histological, and functional alterations in rat respiratory and limb skeletal muscle. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(3):263-272. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kitzman DW, Brubaker P, Morgan T, et al. . Effect of caloric restriction or aerobic exercise training on peak oxygen consumption and quality of life in obese older patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(1):36-46. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.17346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ellingsen Ø, Halle M, Conraads V, et al. ; SMARTEX Heart Failure Study (Study of Myocardial Recovery After Exercise Training in Heart Failure) Group . High-intensity interval training in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Circulation. 2017;135(9):839-849. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Piercy KL, Troiano RP, Ballard RM, et al. . The physical activity guidelines for Americans. JAMA. 2018;320(19):2020-2028. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.14854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Connor CM, Whellan DJ, Lee KL, et al. ; HF-ACTION Investigators . Efficacy and safety of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure: HF-ACTION randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(14):1439-1450. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Morgan TM, Stewart KP, Little WC. Exercise training in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Circ Heart Fail. 2010;3(6):659-667. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.958785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kitzman DW, Brubaker PH, Herrington DM, et al. . Effect of endurance exercise training on endothelial function and arterial stiffness in older patients with heart failure and preserved ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(7):584-592. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gary RA, Sueta CA, Dougherty M, et al. . Home-based exercise improves functional performance and quality of life in women with diastolic heart failure. Heart Lung. 2004;33(4):210-218. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alves AJ, Ribeiro F, Goldhammer E, et al. . Exercise training improves diastolic function in heart failure patients. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(5):776-785. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31823cd16a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schmidt AG, et al. ; Aldo-DHF Investigators . Effect of spironolactone on diastolic function and exercise capacity in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: the Aldo-DHF randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(8):781-791. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solomon SD, McMurray JJV, Anand IS, et al. ; PARAGON-HF Investigators and Committees . Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(17):1609-1620. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1908655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fleg JL, Cooper LS, Borlaug BA, et al. ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Working Group . Exercise training as therapy for heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2015;8(1):209-220. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.113.001420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol

eAppendix. Group Members

eMethods. Description of Multiple Imputation Approach

eFigure 1. Subgroup Analysis of the Primary Endpoint (Change in Peak V̇O2 After 3 Months)

eFigure 2. Relative Frequency of Performed Exercise Training Sessions Within 3-Month and 12-Month Intervention Period in High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) and Moderate Continuous Training (MCT)

eTable 1. Ineligible Participants Not Meeting HFpEF Criteria Who Were Inadvertently Randomized and Excluded From the Analysis

eTable 2. Subgroup Analysis of the Primary Endpoint (Change in Peak V̇O2 After 3 Months)

eTable 3. Results From Cardiopulmonary Exercise Testing for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eTable 4. Results from echocardiography for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eTable 5. Results From Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eTable 6. Exercise Training Data and Adherence to the Prescribed Exercise Intervention for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) and Moderate Continuous Training (MCT)

eTable 7. Group Differences in Primary and Secondary Endpoints After 3 and 12 Months Including Only the Per-Protocol Population of Patients Who Performed at Least 70% of the Scheduled Training Sessions

eTable 8. List of Cardiovascular and the Most Common Non-cardiovascular Adverse Events for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eTable 9. List of Serious Adverse Events (SAEs) for High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT), Moderate Continuous Training (MCT) and Guideline Control

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement