SUMMARY

Early life exposures have been associated with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE), but it is unknown if a similar association is present in adults. We aimed to assess the association between early life risk factors and development of EoE in adulthood. To do this, we conducted a case–control study which was nested within a prospective cohort study of adults undergoing outpatient endoscopy. Cases of EoE were diagnosed per consensus guidelines; controls did not meet these criteria. Subjects and their mothers were contacted to collect information on four key early life exposures: antibiotics taken during the first year of life, Cesarean delivery, preterm delivery (≤37 weeks’ gestation), and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission. We calculated the odds of EoE given in each exposure and assessed agreement between subjects and their mothers. For the 40 cases and 40 controls enrolled, we observed a positive association between each of the early life exposures and development of EoE (antibiotics in infancy, OR = 4.64, 95% CI = 1.63–13.2; Cesarean delivery, OR = 3.08, 95% CI = 0.75–12.6; preterm delivery, OR = 2.92, 95% CI = 0.71–12.0; NICU admission, OR = 4.00, 95% CI = 1.01–15.9). Results were unchanged after adjusting for potential confounders, though only early antibiotic use had CIs that did not cross 1.0. Moderate to strong agreement was observed between 54 subject–mother pairs (antibiotics, K = 0.44, P = 0.02; Cesarean delivery, K = 1.0, P < 0.001; preterm delivery, K = 0.80, P < 0.001; NICU, K = 0.76, P < 0.001). In sum, antibiotics in infancy was significantly associated with increased risk of EoE diagnosed in adulthood, while positive trends were seen with other early life factors such as Cesarean delivery, preterm delivery, and NICU admission. This may indicate persistent effects of early life exposures and merits additional study into conserved pathogenic mechanisms.

Keywords: eosinophilic esophagitis, risk factors, early life, antibiotics, cesarean section

INTRODUCTION

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a clinicopathologic condition characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and a prominent eosinophilic infiltrate in the esophageal epithelium.1 Though the disease is rare, the healthcare burden is substantial.2, 3 The epidemiology has also been evolving, with a marked increase in incidence and prevalence over the past two decades that is outpacing disease recognition and increases in endoscopy and biopsy practices.4–6 This rapid increase suggests that environmental factors, rather than primary genetic changes, likely underlie EoE pathogenesis.7 Though much has been learned about the Th2/allergen-mediated pathways involved in the EoE inflammatory cascade and the resultant chronic changes that lead to fibrosis and esophageal remodelling,8–10 the initial etiologic triggers are unknown and can only be identified in rare cases in given individuals.11

A number of studies have investigated etiologic environmental risk factors, providing some evidence that low population density,12 arid and cold climates,13 summer and fall seasons,14, 15 and possibly some infections16–19 may increase the risk of EoE. Several studies have also evaluated the contribution of early life risk factors to risk of EoE, specifically factors which have been shown to be associated with other atopic and inflammatory conditions.20 These studies of early life factors and EoE have demonstrated that prenatal risk factors, such as maternal infection or fever, and postnatal factors, such as antibiotic administration during infancy, Cesarean delivery, and neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission, are associated with an increased risk of pediatric EoE.21–25 While a high proportion of EoE diagnoses occur in adulthood, it is unknown whether these same early life factors could be implicated in adult-onset of disease.

Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the association between early life risk factors and development of EoE in adulthood. Additionally, given the increased potential for misclassification of exposure status in adults being asked to recall early life experiences, we conducted a secondary analysis to determine the agreement between the report of risk factors between subjects and their mothers. We hypothesized that similar to the relation observed in children, early antibiotic use, Cesarean delivery, NICU admission, and preterm delivery would be associated with EoE and that there would be high agreement in reported risk factors between subjects and their mothers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design and subjects

This was a case–control study nested within a previously conducted prospective cohort study of adults undergoing outpatient endoscopy for evaluation of gastrointestinal symptoms at University of North Carolina. In that prior study, which has been previously described,26–30 subjects were newly diagnosed (incident) EoE cases if they met consensus diagnostic guidelines from the time when the study was designed and patient enrollment, including nonresponse to a proton pump inhibitor (PPI) trial.31, 32 Controls did not meet these criteria and were included as they were felt to reflect the same source population from which the cases were drawn. At the time of original enrollment, all participants provided consent for participation as well as to be contacted for future studies. For the current study, we consecutively contacted previously enrolled cases and controls from the study roster to provide responses to a new set of questions, until we met the projected sample size, as described below. Of note, for EoE cases in particular, we required that both their diagnosis date and their reported symptom onset were after the age of 18. Subjects provided updated informed consent to participate in the current study and provided contact information for their mothers, if available. We subsequently contacted the mothers, who also provided informed consent to participate. The rationale for including mothers in this study was to supplement the subject questionnaire data (in the event a subject did not know the details about an exposure of interest) and to evaluate the potential for misclassification bias of early life exposure status. Both the prior study and the present study were approved by the UNC Institutional Review Board.

Data collection and statistical analysis

All subjects and mothers completed our Early Life Exposure Questionnaire, which was developed in our prior study of early life factors and EoE.21, 24 As this was the first investigation of early life factors and EoE in adults, we focused on four key exposures of interest: any antibiotics taken during the first year of life, Cesarean delivery, preterm delivery (defined as ≤37 weeks’ gestation), and NICU admission. In the event a subject did not know their exposure history, we used the mother’s report. From the prior study, we also had access to data on demographics, major symptoms, atopic status, endoscopic findings, and histologic findings (peak eosinophil count; eosinophils per high-power field [eos/hpf] as determined by our previously validated protocol33, 34).

For analysis, summary statistics were used to characterize the cases and controls, and groups were compared with two-sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square for categorical variables. To test our hypothesis, we used generalized linear models (logit link, binomial distribution) to calculate the odds of EoE given each exposure and calculated 95% confidence intervals. We assessed potential confounders such as age, sex, race, and atopic status using backward elimination and applying a 10% change in estimate approach for inclusion in the final model. Agreement between subjects and their mothers was calculated using Cohen’s kappa. We also performed an additional logistic regression model to assess the odds of EoE, adjusted for age, sex, and race, with one risk factor versus two or more risk factors, compared to a referent of no risk factors. This study did not have a formal sample size calculation, but the goal of 40 subjects in each group was felt sufficient to provide proof of concept, demonstrates feasibility of recruiting mothers of subjects, and was larger than our initial study in children that showed positive results with a smaller sample size.21

RESULTS

Characteristics of the patient population

A total of 40 EoE cases and 40 non-EoE controls were enrolled. Compared to controls, EoE cases were younger (33 vs. 43 years; P < 0.001), were more likely to be white (96 vs. 80%; P = 0.01) and have dysphagia symptoms (100% vs. 75%; P = 0.001), and were less likely to have heartburn symptoms (15% vs. 68%; P < 0.001) (Table 1). As expected, EoE cases were also more likely to have endoscopic features typical of EoE. The mean baseline peak esophageal eosinophil counts were 81 eos/hpf in the cases and 1 eos/hpf in the controls. Of the controls, 22 had gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), 6 had esophageal dysmotility, and 12 had a functional GI disorder.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cases and controls

| Controls (n = 40) | EoE cases (n = 40) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years ± SD) | 42.8 ± 10.9 | 32.5 ± 10.9 | <0.001 |

| Male (n, %) | 15 (38) | 21 (53) | 0.18 |

| White (n, %) | 32 (80) | 39 (96) | 0.01 |

| Dysphagia symptoms (n, %) | 30 (75) | 40 (100) | 0.001 |

| Heartburn/reflux symptoms (n, %) | 27 (68) | 6 (15) | <0.001 |

| Atopy (n, %) | 28 (70) | 29 (73) | 0.81 |

| Baseline endoscopy findings (n, %) | |||

| Rings | 4 (10) | 30 (75) | <0.001 |

| Stricture | 2 (5) | 19 (48) | <0.001 |

| Narrowing | 2 (5) | 14 (35) | <0.001 |

| Furrows | 1 (3) | 35 (88) | <0.001 |

| Exudates | 1 (3) | 25 (63) | <0.001 |

| Edema | 1 (3) | 31 (78) | <0.001 |

| Peak eosinophil count (mean eos/hpf ± SD) | 0.8 ± 2.1 | 81.0 ± 56.8 | <0.001 |

Early life exposures in EoE cases and controls

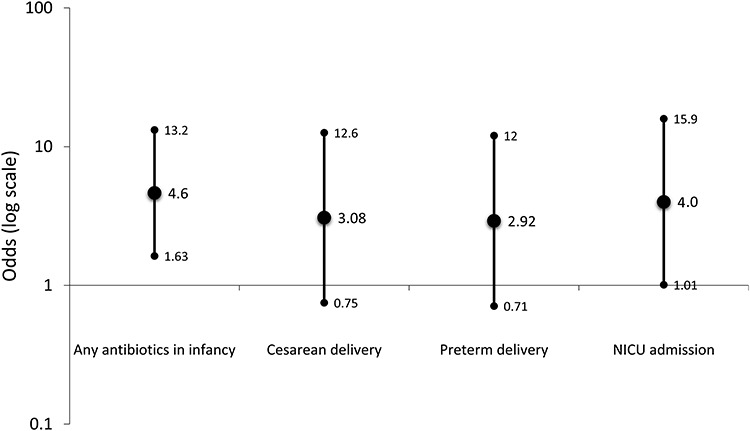

The early life exposures were overall more prevalent in EoE cases as compared to controls. For example, early antibiotic use was reported in 65% of cases compared to 29% of controls (P = 0.003), and NICU admission was noted in 25% of cases compared to 8% of controls (Table 2). Of the overall sample, 12 subjects had 2 risk factors, 2 had 3 risk factors, and 2 had 4 risk factors; therefore, a total of 16 subjects out of 80 (20%) had more than 1 risk factor. Across each of the early life exposures examined, we observed a positive association between exposure and development of EoE in adulthood (antibiotics in infancy, OR = 4.64, 95% CI = 1.63–13.2; C-section, OR = 3.08, 95% CI = 0.75–12.6; preterm delivery, OR = 2.92, 95% CI = 0.71–12.0; NICU admission, OR = 4.00, 95% CI = 1.01–15.9) (Fig. 1). Results were not markedly different after a final model adjusting for age, sex, and race; removal of atopic status from the model did not change the point estimates. In addition, after controlling for age, sex, and race, compared to no risk factors, having any one risk factor had an aOR of 7.88 (95% CI = 2.03–30.6), and having two or more risk factors had an aOR of 17.9 (95% CI = 2.91–110.3).

Table 2.

Odds ratios for exposures of interest between cases and controls

| Exposure | Controls | Cases | P | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR* (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | |||||

| n total | 28 | 40 | |||

| n (%) | 8 (29) | 26 (65) | 0.003 | 4.64 (1.63–13.2) | 3.51 (1.01–12.2) |

| C-section | |||||

| n total | 40 | 40 | |||

| n (%) | 3 (8) | 8 (20) | 0.10 | 3.08 (0.75–12.6) | 6.21 (0.65–59.3) |

| Preterm delivery | |||||

| n total | 38 | 40 | |||

| n (%) | 3 (8) | 8 (20) | 0.13 | 2.92 (0.71–12.0) | 2.56 (0.48–13.8) |

| NICU | |||||

| n total | 39 | 40 | |||

| n (%) | 3 (8) | 10 (25) | 0.04 | 4.00 (1.01–15.9) | 3.24 (0.69–15.2) |

*Adjusted for age, sex, and race.

Fig. 1.

Odds ratios for early life exposures and development of EoE in cases compared to controls.

Agreement between subjects and mothers

We were able to contact 38 of the 40 mothers of EoE cases (95%) and 16 of the 21 mothers of control subjects (76%) who were not deceased and who were currently living within the United States. Moderate to strong agreement in survey responses was observed for the 54 subject–mother pairs examined (antibiotics, K = 0.44, P = 0.02; Cesarean delivery, K = 1.0, P < 0.001; preterm delivery, K = 0.80, P < 0.001; NICU, K = 0.76, P < 0.001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Agreement between subject report and mother report for exposures of interest (n = 54 subject–mother pairs)

| Exposure | Agreement (%) | Kappa | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 71 | 0.44 | 0.02 |

| C-section | 100 | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Preterm delivery | 94 | 0.80 | <0.001 |

| NICU | 94 | 0.76 | <0.001 |

DISCUSSION

Despite the rapid increase in EoE incidence and prevalence and the large body of knowledge developed about EoE pathogenesis, the initial etiologic trigger in a given individual has been difficult to identify.4, 8 While previous studies have demonstrated that selected early life exposures are associated with an increased risk of pediatric EoE,21–24 it has not been known if the same exposures might be associated with increased risk of EoE in adults. In this study, which to our knowledge is the first to assess these risk factors in adults, we found a positive association between antibiotics in infancy and subsequent diagnosis of EoE as an adult, as well as positive trends with Cesarean section, preterm delivery, and NICU admission. Additionally, with the recognition that adult patients might not know some of their early life details and that recall (resulting in misclassification) bias would be a possibility, we obtained the same exposure information for the subject’s mother and found moderate to strong agreement for all four risk factors examined. Last, we noted that odds of EoE were increased with an increasing number of risk factors in combination.

The rationale for assessing the contribution of early life factors in EoE patients is that this time frame is a sensitive time for immune maturation and developmental susceptibility.35, 36 EoE has also been proposed as a last step in the atopic march; thus initial predisposition to allergic conditions could also increase the likelihood of EoE.37 There have been four previous case–control studies of early life risk factors in EoE in pediatric populations.21–24 While these all differed somewhat in methodology and exposures assessed, and while one only noted a weak inverse association between postnatal tobacco smoke exposure and subsequent EoE,23 the other three studies were generally consistent in their findings. Antibiotic exposure within the first year of life and Cesarean delivery consistently showed a positive association with pediatric EoE; other notable risk factors included acid suppression, absence of furred pets, and NICU admission.21, 22, 24

While the exact mechanisms through which these early life exposures increase the risk of EoE is not known, one proposed hypothesis is that they may impact the developing microbiome.7, 20 However, the reality may be more complicated, particular if gene–environment interactions are taken into consideration. One example of this are the equivocal results related to breastfeeding when this is examined simply as an environmental risk factor.21 In recent work, a single-nucleotide polymorphism in the CAPN14 (calpain 14) gene, which is integral in maintaining barrier function in the esophagus,38, 39 was examined.25 In patients without the susceptibility genotype, breastfeeding status did not impact subsequent EoE risk. However, patients with the risk allele who were not breastfed had higher odds of EoE than those who were breastfeed.25 While the present study does not investigate mechanisms, the results are consistent with the prior pediatric literature in that early life factors such as antibiotic exposure in infancy and NICU admission were significant associated with EoE in adults and there was a strong positive trend toward association for Cesarean delivery and preterm birth.21, 22, 24 It is very interesting that these early life factors appear to increase risk for EoE in adults, and future studies will need to assess possible shared pathogenic mechanisms, the role of gene–environment interaction, and the issue of repeated exposures (for example with antibiotics).

In addition to lack of mechanistic information, we acknowledge that this study has some limitations. First, it is a relatively small sample of EoE cases and controls, but even with the current sample size, we found moderate effect sizes, and though estimates were imprecise and without a formal sample size calculation, the study was likely underpowered. Second, we assessed only a limited set of early life exposures, but as this was the first study in adults, it mirrors our initial study in children and shows proof of principle.21 Future studies should investigate a wider range of exposures and timings and also determine the extent to which these risk factors are independent. It is possible that a subject could have preterm delivery, a NICU admission, and antibiotics at the same time, though only 20% of our sample had two or more risk factors. With this, we found that the odds of EoE increased with an increasing number of risk factors in combination. Third, recall and reporting biases are potential concerns for any study assessing exposures that happened many years in the past. We believe this is less likely for objective measures such as Cesarean delivery (which is not likely to be forgotten by mothers), NICU admission, or preterm birth, and the high rates of agreement and kappa values between the subjects and their mothers bear this out. However, this is not the case with antibiotic exposures, and the lower (but still moderate) agreement and kappa suggest that when possible more objective measures should be used, for example, prescription records or medical chart abstraction. Finally, our case definition did not include patients who would now be defined as EoE cases who respond to PPI treatment, as these patients were not considered to have EoE at the time this study was conducted.1 Therefore, future studies should also assess PPI responders and PPI naïve cases. Our study also has multiple strengths, including drawing cases and controls from a prior prospective study, a strong nested case–control design, prospective and direct contact of subjects to collect new exposure data, and the unique use of subject’s mothers to corroborate data and assess agreement in exposure recall.

In conclusion, antibiotics in infancy was significantly associated with increased risk of EoE diagnosed in adulthood, while positive trends were seen with other early life factors such as Cesarean delivery, preterm delivery, and NICU admission. These results are similar to previously reported associations in children and indicate persistent effects of early life exposures into adulthood. Our findings merit additional study to confirm relationships and investigate possible conserved pathogenic mechanisms.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Dellon: Project conception, study design, data collection, data analysis/interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision, Shaheen: Data collection, critical revision, Koutlas: Data collection, critical revision, Chang: Data collection, critical revision, Martin: Data interpretation, critical revision, Rothenberg: Data interpretation, critical revision, and Jensen: Project conception, study design, data analysis/interpretation, manuscript drafting, critical revision.

FINANCIAL SUPPORT

This study was supported by NIH (awards K23DK090073, R01DK101856, and T35DK007386).

DISCLOSURES

None of the coauthors report any relevant potential conflicts of interest. MER is a consultant for PulmOne, Spoon Guru, ClostraBio, Serpin Pharm, Celgene, AstraZeneca, Allakos, Arena Pharmaceuticals, Guidepoint, and Suvretta Capital Management; has an equity interest in the first four listed and royalties from reslizumab (Teva Pharmaceuticals), PEESSv2 (Mapi Research Trust), and UpToDate; and is an inventor of patents owned by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. ESD is a consultant for Abbott, Adare, Aimmune, Allakos, Arena, AstraZeneca, Biorasi, Calypso, Celgene/Receptos, Eli Lilly, EsoCap, GSK, Gossamer Bio, Regeneron, Robarts, Salix, Shire/Takeda and has received research funding from Adare, Allakos, GSK, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Celgene/Receptos, Regeneron, and Shire/Takeda and educational grants from Allakos, Banner, and Holoclara.

REFERENCES

- 1. Dellon E S, Liacouras C A, Molina-Infante J et al. Updated international consensus diagnostic criteria for eosinophilic esophagitis: proceedings of the AGREE conference. Gastroenterology 2018; 155: 1022–33.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jensen E T, Kappelman M D, Martin C F, Dellon E S. Health-care utilization, costs, and the burden of disease related to eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110(5): 626–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Leiman D A, Kochar B, Posner S et al. A diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with increased life insurance premiums. Dis Esophagus 2018; 31(8): doy008. doi: 10.1093/dote/doy008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dellon E S, Hirano I. Epidemiology and natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: 319–22.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dellon E S, Erichsen R, Baron J A et al. The increasing incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis outpaces changes in endoscopic and biopsy practice: national population-based estimates from Denmark. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 41: 662–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giriens B, Yan P, Safroneeva E et al. Escalating incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis in Canton of Vaud, Switzerland, 1993-2013: a population-based study. Allergy 2015; 70: 1633–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jensen E T, Dellon E S. Environmental factors and EoE. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 142: 32–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. O'Shea K M, Aceves S S, Dellon E S et al. Pathophysiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2018; 154: 333–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hirano I, Aceves S S. Clinical implications and pathogenesis of esophageal remodeling in eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2014; 43(2): 297–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eluri S, Tappata M, Huang K Z et al. Distal esophagus is the most commonly involved site for strictures in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus 2020; 33(2): doz088. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wolf W A, Jerath M R, Dellon E S. De-novo onset of eosinophilic esophagitis after large volume allergen exposures. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2013; 22(2): 205–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jensen E T, Hoffman K, Shaheen N J, Genta R M, Dellon E S. Esophageal eosinophilia is increased in rural areas with low population density: results from a national pathology database. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109(5): 668–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hurrell J M, Genta R M, Dellon E S. Prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia varies by climate zone in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107(5): 698–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Jensen E T, Shah N D, Hoffman K, Sonnenberg A, Genta R M, Dellon E S. Seasonal variation in detection of oesophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2015; 42: 461–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Reed C C, Iglesia E G A, Commins S P, Dellon E S. Seasonal exacerbation of eosinophilic esophagitis histologic activity in adults and children implicates role of aeroallergens. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2019; 122: 296–301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dellon E S, Peery A F, Shaheen N J et al. Inverse association of esophageal eosinophilia with helicobacter pylori based on analysis of a US pathology database. Gastroenterology 2011; 141(5): 1586–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Von Arnim U, Wex T, Miehlke S, Link A, Malfertheiner P. Inverse correlation of H. pylori and eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology 2014; 146(Suppl 1): S-677 (Mo1869). [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zimmermann D, Criblez D H, Dellon E S et al. Acute herpes simplex viral esophagitis occurring in 5 immunocompetent individuals with eosinophilic esophagitis. ACG Case Rep J 2016; 3(3): 165–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Srivastava M D M Pneumoniae is a potential trigger for Eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2013; 131(Suppl): AB177. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Muir A B, Benitez A J, Dods K, Spergel J M, Fillon S A. Microbiome and its impact on gastrointestinal atopy. Allergy 2016; 71(9): 1256–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jensen E T, Kappelman M D, Kim H P, Ringel-Kulka T, Dellon E S. Early life exposures as risk factors for pediatric Eosinophilic esophagitis: a pilot and feasibility study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2013; 57(1): 67–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Radano M C, Yuan Q, Katz A et al. Cesarean section and antibiotic use found to be associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2014; 2(4): 475–7 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Slae M, Persad R, Leung A J, Gabr R, Brocks D, Huynh H Q. Role of environmental factors in the development of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 2015; 60: 3364–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Jensen E T, Kuhl J T, Martin L J, Rothenberg M E, Dellon E S. Prenatal, intrapartum, and postnatal factors are associated with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 214–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jensen E T, Kuhl J T, Martin L J, Langefeld C D, Dellon E S, Rothenberg M E. Early life environmental exposures interact with genetic susceptibility variants in pediatric patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2018; 141: 632–7.e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dellon E S, Rusin S, Gebhart J H et al. Utility of a non-invasive serum biomarker panel for diagnosis and monitoring of EoE: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 821–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dellon E S, Rusin S, Gebhart J H et al. A clinical prediction tool identifies cases of eosinophilic esophagitis without endoscopic biopsy: a prospective study. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110: 1347–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Eluri S, Perjar I, Betancourt R et al. Heartburn and dyspepsia symptom severity improves after treatment and correlates with histology in adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus 2019; 32(9): doz028. doi: 10.1093/dote/doz028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Koutlas N T, Eluri S, Rusin S et al. Impact of smoking, alcohol consumption, and NSAID use on risk for and phenotypes of eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus 2018; 31(1): 1–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wolf W A, Piazza N A, Gebhart J H et al. Association between body mass index and clinical and endoscopic features of eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Dis Sci 2017; 62(1): 143–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Liacouras C A, Furuta G T, Hirano I et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2011; 128: 3–20.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Dellon E S, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta G T, Liacouras C, Katzka D A. ACG clinical guideline: evidence based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108(5): 679–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dellon E S, Fritchie K J, Rubinas T C, Woosley J T, Shaheen N J. Inter- and intraobserver reliability and validation of a new method for determination of eosinophil counts in patients with esophageal eosinophilia. Dig Dis Sci 2010; 55(7): 1940–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rusin S, Covey S, Perjar I et al. Determination of esophageal eosinophil counts and other histologic features of eosinophilic esophagitis by pathology trainees is highly accurate. Hum Pathol 2017; 62: 50–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Butel M J, Waligora-Dupriet A J, Wydau-Dematteis S. The developing gut microbiota and its consequences for health. J Dev Orig Health Dis 2018; 9(6): 590–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Georgountzou A, Papadopoulos N G. Postnatal innate immune development: from birth to adulthood. Front Immunol 2017; 8: 957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hill D A, Grundmeier R W, Ramos M, Spergel J M. Eosinophilic esophagitis is a late manifestation of the allergic march. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract 2018; 6(5): 1528–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Davis B P, Stucke E M, Khorki M E et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis-linked calpain 14 is an IL-13-induced protease that mediates esophageal epithelial barrier impairment. JCI Insight 2016; 1(4): e86355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Litosh V A, Rochman M, Rymer J K, Porollo A, Kottyan L C, Rothenberg M E. Calpain-14 and its association with eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2017; 139(6): 1762–1771.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]