Abstract

Pediatric sepsis is a major public health problem. Published treatment guidelines and several initiatives have increased adherence with guideline recommendations and have improved patient outcomes, but the gains are modest, and persistent gaps remain. The Children’s Hospital Association Improving Pediatric Sepsis Outcomes (IPSO) collaborative seeks to improve sepsis outcomes in pediatric emergency departments, ICUs, general care units, and hematology/oncology units. We developed a multicenter quality improvement learning collaborative of US children’s hospitals. We reviewed treatment guidelines and literature through 2 in-person meetings and multiple conference calls. We defined and analyzed baseline sepsis-attributable mortality and hospital-onset sepsis and developed a key driver diagram (KDD) on the basis of treatment guidelines, available evidence, and expert opinion. Fifty-six hospital-based teams are participating in IPSO; 100% of teams are engaged in educational and information-sharing activities. A baseline, sepsis-attributable mortality of 3.1% was determined, and the incidence of hospital-onset sepsis was 1.3 cases per 1000 hospital admissions. A KDD was developed with the aim of reducing both the sepsis-attributable mortality and the incidence of hospital-onset sepsis in children by 25% from baseline by December 2020. To accomplish these aims, the KDD primary drivers focus on improving the following: treatment of infection; recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of sepsis; de-escalation of unnecessary care; engagement of patients and families; and methods to optimize performance. IPSO aims to improve sepsis outcomes through collaborative learning and reliable implementation of evidence-based interventions.

Sepsis is a leading cause of death among infants and children and has been increasingly recognized as a public health problem in the United States and worldwide.1,2 Despite the differences in sepsis definitions, retrospective diagnosis code–based studies have demonstrated a large number of US children are hospitalized annually for severe sepsis (75 000 to 100 000 by various estimates) with mortality rates of 5% to 20%.3–6 Global sepsis burden of disease is estimated to affect 1.2 million children annually, with a point prevalence of ~8% of PICU hospitalizations.7,8 Moreover, recent studies have indicated the incidence of severe sepsis in US children’s hospitals has increased, although the mortality rate has decreased slightly.4,5

Recommendations for the identification and treatment of pediatric sepsis by the Society of Critical Care Medicine, the American Heart Association, and the Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC)9–13 have prompted efforts to improve sepsis care. Single-center emergency department (ED)–focused quality improvement (QI) initiatives have revealed substantial increases in adherence with these recommendations and were associated with improved patient outcomes.14–17 The Pediatric Septic Shock Collaborative, a 15-hospital QI initiative for management of sepsis, demonstrated improvement in prompt clinical assessment with modest improvements in timely administration of fluid resuscitation and antibiotics, but with no improvement in mortality18; a subsequent 19-hospital ED-focused initiative revealed a modest decrease in 30-day in-hospital all-cause mortality (H. Depinet, MD, MPH, personal communication, 2020). An impact analysis of state regulations intended to improve the quality of sepsis care in New York hospitals demonstrated increased use of sepsis treatment protocols that included the SSC pediatric intervention bundle.11,19 Completion of the entire sepsis bundle within 1 hour was associated with a 40% decrease in risk-adjusted in-hospital mortality; however, bundle completion occurred for only 25% of the patients.20

These findings highlight the need for a larger multicenter QI learning collaborative to standardize early detection and rapid, comprehensive treatment of sepsis, to engage participants and teams from multiple institutions to succeed more effectively in rapid-cycle improvement, and to foster collaborative learning within and among institutions. By creating such a collaborative, lessons learned and data collected can be shared widely and interventions assessed for success.21 There are many examples of similar successful QI learning collaboratives.17,22–26 The Children’s Hospital Association (CHA) has undertaken the goal of developing and supporting a pediatric sepsis QI learning collaborative in acute care settings in the United States by creating the Improving Pediatric Sepsis Outcomes (IPSO) project. Using the framework outlined by Britto et al,21 we describe the structure, aims, interventions and mobilization of the IPSO collaborative.

DEVELOPING THE IPSO COLLABORATIVE: LEARNING NETWORK ORGANIZATIONAL ARCHITECTURE

Aligning Participants Around a Common Goal

Founded in 2015, IPSO is a CHA-supported QI learning collaborative focused on the goal of decreasing sepsis-attributable mortality and preventing hospital-onset sepsis among children through appropriate, timely, and reliable implementation of evidence-based diagnostic and clinical care processes. Explicit in this goal is an effort to reduce progression of infection to organ dysfunction or hemodynamic compromise and septic shock among hospitalized children. In addition to reducing sepsis-attributable mortality, the goal of this QI learning collaborative was to reduce the impact of sepsis on morbidity.

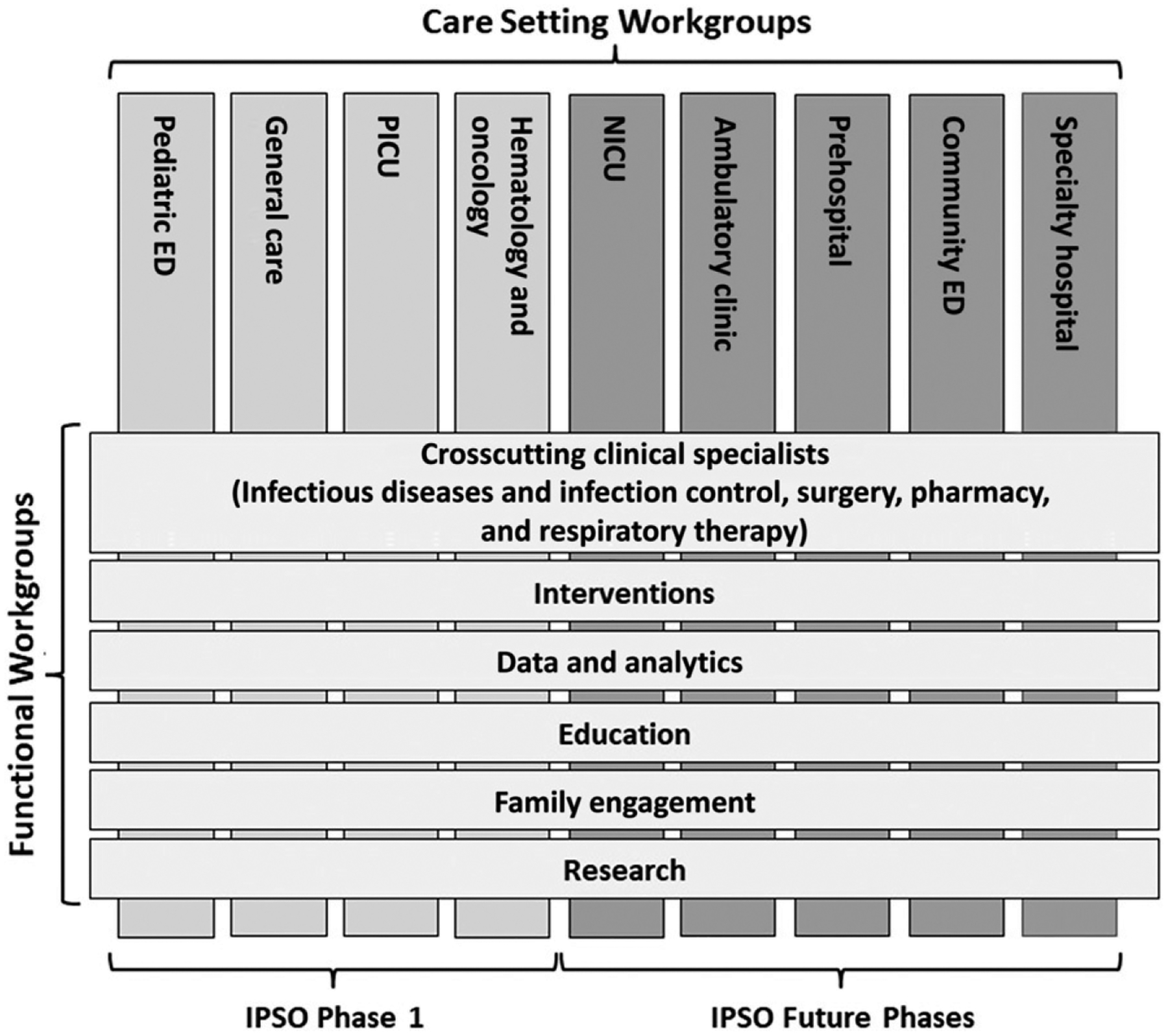

To launch IPSO, CHA leadership convened a multispecialty, multidisciplinary panel of >60 sepsis experts from 40 institutions, chosen for their expertise in various care settings and across key functional activities (Fig 1). Panel members representing key stakeholder groups were selected to form a steering committee led by 3 physician cochairs representing PICU, ED, and hospital executive leadership perspectives and by CHA administrative leaders. The panel determined the initial focus and aims of the collaborative. The steering committee refined the aims, identified interventions, and designed mobilization strategies.

FIGURE 1.

Structure of the CHA IPSO collaborative.

At the time the QI learning collaborative was launched, definitions of pediatric sepsis, severe sepsis, and septic shock were based on multidisciplinary expert panel consensus definitions published by Goldstein et al.27 These definitions, although intended to standardize terminology for research and sepsis surveillance in pediatric patients, have limitations when applied to direct, real-time clinical care.28 The steering committee decided that terminology useful in a QI learning collaborative should focus on implementing and measuring real-time care practices. The IPSO terminology (Table 1) evolved on the basis of the need to do the following: (1) identify patients with sepsis in real time and focus on abnormal vital signs, perfusion, and mental status to treat them promptly; and (2) retrospectively categorize the severity of illness among patients with sepsis to better assess project success in achieving its aims. IPSO Suspected Infection categorized patients who might have had an infection and were at risk for progression to sepsis on the basis of a clinician’s decision to obtain a blood culture, administer an antibiotic, and admit the patient to the hospital if not already hospitalized. Using IPSO sepsis, we identified hospitalized patients thought to have sepsis on the basis of 1 of 8 criteria indicating that bedside providers believed the patient may have sepsis (Table 1).29 IPSO critical sepsis is a subset of patients with IPSO sepsis who likely had septic shock.

TABLE 1.

Definitions of Terms Used in the CHA IPSO QI Learning Collaborative

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| IPSO suspected infection | Hospitalized patients or ED patients designated for admission who had a blood culture collected and an antibiotic administered within 24 h of each other |

| IPSO sepsis | Hospitalized patients or ED patients who met ≥1 of the following 8 criteria29: a bedside screen positive for sepsisa and treatment of sepsis,b a positive huddle for sepsis,c use of an electronic medical record order set for severe sepsis or use of an electronic medical record order set for sepsis that included treatment of sepsis,b ICU admission and treatment of sepsis,b collection of a venous or arterial lactate level and treatment of sepsis,b administration of a vasopressor and treatment of sepsis,b use of ICD-10 billing codes R65.20 or R65.21, or use of other specified sepsis ICD-10 billing codes and treatment of sepsisb |

| IPSO critical sepsis | Hospitalized patients or ED patients who met the IPSO sepsis definition and met ≥1 of the following criteria: administration of a first antibiotic plus 2 IV fluid boluses (all within 6 h of each other) plus administration of a third IV fluid bolus, administration of a first antibiotic plus 2 IV fluid boluses (all within 6 h of each other) plus administration of a vasopressor, or administration of a first antibiotic plus an IV fluid bolus plus administration of a vasopressor (all within 6 h of each other) |

| Sepsis-attributable mortality | Patients who met the IPSO sepsis definition and who died were reviewed to determine if the patient had IPSO sepsis and no comorbid conditions or had a comorbid condition but had not fully recovered from all sepsis-related organ dysfunction before death |

ICD-10, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision; IV, intravenous.

Determined at individual sites but generally consistent with the Pediatric Sepsis and Septic Shock Collaborative definition, which includes assessment of underlying risk and abnormal vital signs, perfusion, and mental status.16

Administration of an antibiotic and an IV fluid bolus plus either a second IV fluid bolus or administration of a vasopressor (all within 6 h of each other) plus a blood culture collected within 72 h of the episode.

A brief, focused discussion that includes a nurse, a provider (physician, physician assistant, or nurse practitioner), and additional staff as needed (eg, rapid response team, code sepsis team, or care team) during which a determination is made that the patient will be treated for sepsis.

One of the goals of the IPSO collaborative is to address the recognition and care of patients with sepsis across the health care continuum (Fig 1). Initial IPSO work has focused on ED, PICU, general care, and hematology/oncology units because of the frequency of occurrence and significant risk of either unrecognized or rapidly progressive sepsis in these settings.

The steering committee developed the aims for the QI learning collaborative based on the latest available literature to identify sepsis all-cause mortality rate and hospital-onset sepsis incidence in US acute care settings. The original aims established in 2015 were based on best available evidence at that time (Table 2). Sepsis all-cause mortality was initially estimated at ~10%.3–6 The incidence of hospital-onset sepsis was initially estimated at 2% (on the basis of review of pediatric epidemiology data, pooled nosocomial infection data, and rough estimate).3–6 On the basis of results demonstrated from other sepsis-related QI initiatives, the committee initially estimated 75% reductions were possible for both outcomes (Table 2).14–17 However, in 2019, IPSO revised the aims based on actual collaborative data and switched the mortality outcome measure from “all cause” to “sepsis attributable” (Table 2). The IPSO physician leader from each participating hospital evaluated their mortality cases to determine comorbid conditions and mortality association with a sepsis event so that a stronger link to IPSO interventions could be determined (Table 1). Because the sepsis-attributable mortality and incidence of hospital-onset sepsis during the collaborative baseline period were substantially lower than initial estimates, a more modest reduction of 25% was viewed as feasible, while remaining an aspirational and clinically important improvement in these outcomes. In addition, the revised mortality aim also focused on a critically ill subset of patients with sepsis (IPSO critical sepsis). The revised 2019 IPSO aims are twofold: (1) reduce sepsis-attributable mortality by at least 25% from baseline and (2) reduce hospital-onset IPSO critical sepsis by at least 25%, both by December 2020 (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

CHA IPSO QI Learning Collaborative Aims

| Initial Aim Based on Projected Baseline Rate | Measured Baseline Rate | Revised Aim Based on Measured Baseline Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Reduce IPSO sepsis 30-d all-cause mortality by 75% from 10.0% to 2.5% by December 2020 | 30-d sepsis-attributable mortality: IPSO sepsis: 3.1% during 2016; IPSO critical sepsis: 3.6% during 2017 | Reduce 30-d sepsis-attributable mortality by at least 25% from the measured baseline rate by December 2020: IPSO sepsis target: 2.3%; IPSO critical sepsis target: 2.7% |

| Reduce the incidence of hospital- onset IPSO sepsis by 75% from 2.0% to 0.5% of IPSO suspected infection cases by December 2020 | Incidence of hospital-onseta IPSO critical sepsis: 1.3 cases per 1000 hospital admissions during 2017 | Reduce the incidence of hospital-onseta IPSO critical sepsis by at least 25% from the measured baseline incidence by December 2020: IPSO critical sepsis target: 1.0 cases per 1000 hospital admissions |

Hospital-onset is defined as occurring ≥12 hours after arrival in the ED or admission to the hospital.

Standards, Processes, Policies, and Infrastructure to Enable Collaboration

The steering committee developed policies for the QI learning collaborative. Hospitals eligible for collaborative participation were CHA member hospitals. Hospitals were recruited by advertising on the CHA Web site, during CHA-sponsored sepsis-focused webinars, during national and academic presentations by cochairs, and by targeted e-mail invitations and other communications with individual hospital leaders. Institutional leaders were required to execute a participation agreement, agreeing to adhere to principles of transparency and to IPSO’s confidentiality requirements. The agreement gave participating hospitals access to quality outcomes from their hospital and other hospitals and aggregate collaborative data.

Care Setting workgroups, composed of multidisciplinary experts, focused on aspects of care and opportunities for improvement in each setting, and on aligning efforts across the continuum of care in the ED, PICU, general care, and hematology/oncology care settings. The alignment included a focus on cross-discipline clinical specialties (eg, junior and senior physicians, nurses, infectious diseases and infection control nurses and physicians, surgeons, pharmacists, and respiratory therapists), interventions, education, data and analytics, family engagement, and research (Fig 1). The work of these groups was conducted through multiple in-person and phone conferences to ensure coordination between work groups and with oversight by the steering committee.

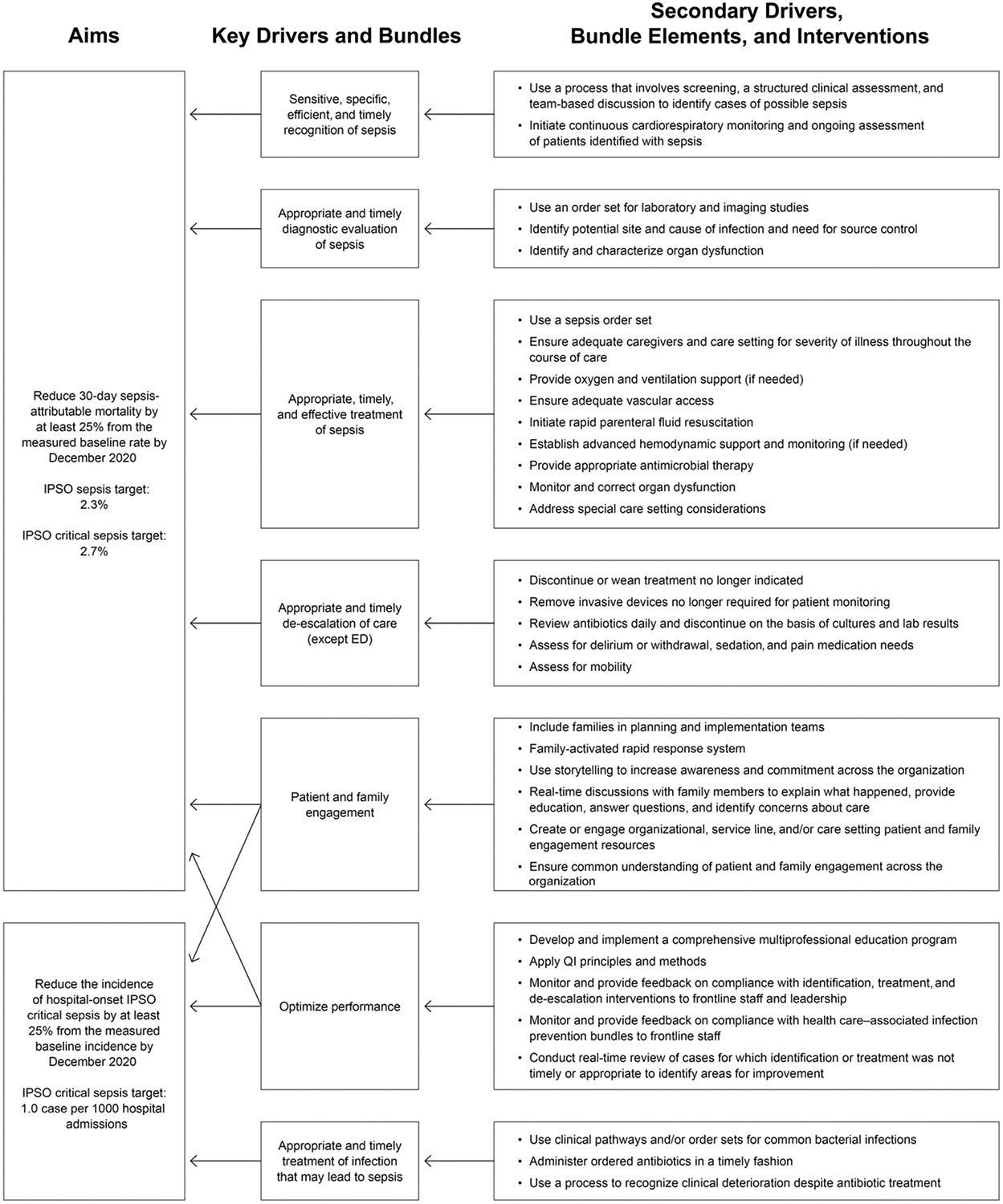

Based on the aims, the interventions workgroup led the care setting workgroups in the development of a key driver diagram (KDD) (Fig 2). They focused first on identifying the primary drivers necessary to achieve the aims, including treatment of infection; recognition, diagnosis, and treatment of sepsis; de-escalation of unnecessary care; engagement of patients and families; and methods to optimize performance. They then identified key tasks and decision points relevant for each of the primary drivers and for each potential stage of sepsis and developed a set of secondary drivers, with attention to the specific needs of patients in the different care settings (Fig 2). To optimize synergy with other national efforts, the secondary drivers were developed and worded to ensure consistency with recommendations of the 2012 Surviving Sepsis and 2014 Society of Critical Care Medicine guidelines for pediatric and neonatal septic shock recognition and care, whenever possible and appropriate.11,12 An evidence table (Supplemental Fig 4) was compiled to identify published reports and professional society guidelines that served as references for the secondary drivers (interventions bundle) elements. Leaders from the Accreditation Commission of Colleges of Medicine, SSC, and Pediatric Septic Shock Collaborative national sepsis efforts were included to ensure that the IPSO recommendations were consistent with these efforts. To supplement the KDD, an implementation manual was created that defined the goals, target populations, and target clinicians for each of the primary drivers and provided a detailed description of the secondary drivers. After publication of the 2020 Pediatric SSC guidelines,30,31 the IPSO Steering Committee carefully reviewed the IPSO KDD documents in reference to the SSC recommendations and determined that no adjustments to the KDD were required.

FIGURE 2.

CHA IPSO collaborative KDD to decrease the incidence of hospital-onset sepsis and mortality from sepsis in pediatric patients.

QI learning collaborative success is dependent on the work done by teams at participating hospitals. To promote their success, IPSO provided a systematic mobilization guide (Fig 3) for participating hospital teams. The first step was to mobilize a hospital-wide partnership of stakeholders with an effective organizational structure to assess resources and readiness, map key processes, identify necessary changes, plan implementation of these changes, and train front-line providers. Stakeholders represented a wide range of expertise and experience, including front-line medical and nursing caregivers, hospital leaders, family advisors, pharmacists, laboratory technicians, infectious disease physicians, infection preventionists, and respiratory therapists. Specifically, family advisors provided insight from personal experience with sepsis to help design sepsis recognition across the continuum of care to reflect importance and value of family involvement and education. Hospitals were encouraged to prioritize and implement the recommended key strategies, which included screening for sepsis, conducting multidisciplinary team–based huddles to perform more detailed clinical assessment for suspected or confirmed sepsis for patients identified by the screen, and using an order set to standardize therapy for these patients. Hospitals were encouraged to monitor their performance with respect to the use of these strategies and to use rapid-cycle tests of change to improve their performance. Concurrent with implementing these changes, hospital teams developed ways to identify, collect, and validate data regarding process and outcome metrics, to submit the data through a common data portal, and to review monthly reports of their performance from the collaborative. Each hospital established a participation agreement for the transfer of limited data sets to the IPSO registry for QI purposes. At some hospitals, institutional review board approval was required as part of this process; at other sites, either an alternative QI governance board approved the data gathering or the data gathering was considered exempt from institutional review board review. This reflects the variation in institutional interpretations of the data regulatory requirements for QI.

FIGURE 3.

CHA IPSO collaborative hospital mobilization guide. IV, intravenous.

A Learning Network to Create and Share Resources to Achieve Shared Goals

IPSO and CHA leadership support a comprehensive collaboration effort for participating teams to calibrate queries, to assist with data submission, and to share tools developed at individual participating institutions (Fig 3). The IPSO collaborative culture emphasizes transparent data sharing, free tools exchange, and an “all-teach, all-learn” model of collaboration.

On an ongoing basis, CHA IPSO staff provide multiple opportunities for hospital-based teams to collaborate, to learn from collaborative and external subject matter experts, to share experiences and learning opportunities, and to network with each other (Fig 3). These activities included biweekly office hours conference calls with CHA QI consultants and data specialists, monthly hot topic interactive webinars with CHA QI consultants and member hospitals, ad hoc care setting webinars, monthly data webinars with data specialists, periodic sepsis education and training webinars, and semiannual face-to-face workshops for peer-to-peer learning and collaboration. The semiannual workshops provide opportunity to share research and other achievements through abstract submission and poster presentation (Fig 3). Hospital representatives have access to other resources, including a web-based library of training modules, clinical bundles, data specifications, implementation ideas, tools and resources contributed by member hospitals, online discussion boards, project and data help desks, and direct coaching by CHA QI consultants, data specialists, and subject matter experts on request. Hospital-based teams from 56 children’s hospitals currently participate in IPSO with 100% engaged in some or all the various educational and information-sharing activities.

DISCUSSION

The IPSO collaborative design includes the key elements of building a successful QI learning collaborative as described by Britto et al.21 First, the focus on sepsis to improve clinical care and outcomes is demonstrably important to patients, their families, and health care providers. Second, the QI learning collaborative seeks to gather data from all participating hospitals to assess performance pertaining to identified standards for care and to identify and learn from best practices. The collaborative seeks transparent sharing of performance data to enhance learning from practice variation between centers. Third, use of QI methods demonstrates the collective and individual hospitals’ improvement over time as goals are reached and obstacles overcome. Fourth, the collaborative creates an infrastructure facilitating connectivity between individuals working in different institutions but facing similar challenges. IPSO provides a framework and a platform to assist providers in sharing information and resources across different specialties and disciplines. This network includes a multidisciplinary team (eg, physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and informaticists), patients and families, administrators, and QI specialists. Fifth, the QI learning collaborative design, with shared, transparent goals and data structure, provides the support for successful research endeavors with ready access to an engaged network of providers and hospitals. In contrast, the IPSO collaborative differs from previous multicenter pediatric efforts through its scope and breadth of patient type and setting inclusion, notably by concentrating on the treatment of sepsis and, more importantly, the prevention of sepsis. The KDD is detailed with specific primary and secondary drivers to guide teams in their improvement work. The QI learning collaborative learning structure is robust, exemplified by revision of the original aims after baseline data analysis. The structure and design of IPSO provides a model for multicenter QI work, highlighting some of the challenges faced, barriers overcome, and opportunities deployed to achieve improvements in care processes and patient outcomes.

One of the many challenges facing a pediatric sepsis QI learning collaborative is that sepsis represents a spectrum of disease with a changing landscape of definitions, tools for recognition, and understanding of risk for mortality and other outcomes. For example, updated SSC management guidelines for pediatric septic shock and sepsis-associated organ dysfunction were published in 2020.30,31 After careful review, we believe the elements of the KDD (Fig 2) are consistent with the SSC management guidelines, and that the guidelines provide best practice recommendations for additional specific care practices, accompanied by an updated summary of the evidence. One of the strengths of the IPSO collaborative in dealing with these challenges is its adaptability as a QI learning collaborative. The steering committee established initial definitions and goals, then later modified the definitions and goals as collaborative baseline data were gathered and analyzed. The revisions of the definitions, severity of illness categorization, and mortality outcomes more optimally meet the needs and goals of the IPSO collaborative and the larger sepsis research and clinical care community. In the future, the IPSO collaborative seeks to expand its work to include high-risk patients in specialty hospitals and NICUs and patients in other settings, such as ambulatory clinics, preclinical locations, and community EDs (Fig 1).

Supplementary Material

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE:

Multiple authors and collaborative investigators, as members of the Children’s Hospital Association’s Improving Pediatric Sepsis Outcomes Steering Committee, received travel reimbursements after attendance at biannual leadership meetings (Drs Auletta, Balamuth, Brilli, Hueschen, Huskins, Kandil, Larsen, Macias, Mack, Niedner, Paul, Razzaqi, Schafer, Scott, Silver, Stalets, and Depinet, and Ms Campbell, Ms Dykstra-Nykanen, and Ms Wathen); the other authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Supported by the Children’s Hospital Association and Quality Improvement Learning Collaborative participant fees and in-kind support from the Children’s Hospital Association.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CHA

Children’s Hospital Association

- ED

emergency department

- IPSO

Improving Pediatric Sepsis Outcomes

- KDD

key driver diagram

- QI

quality improvement

- SSC

Surviving Sepsis Campaign

Footnotes

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Multiple authors, as members of the Children’s Hospital Association’s Improving Pediatric Sepsis Outcomes Steering Committee, received travel reimbursements after attendance at biannual leadership meetings (Drs Auletta, Balamuth, Brilli, Depinet, Hueschen, Huskins, Kandil, Larsen, Macias, Mack, Niedner, Paul, Razzaqi, Schafer, Scott, Silver, and Stalets, and Ms Campbell, Ms Dykstra-Nykanen and Ms Wathen). Dr Scott’s institution is receiving ongoing career development salary support from the Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (K08HS025696). Dr Scott’s institution is receiving ongoing grant support from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development for a research grant (R01HD087363). Dr Huskins reports receiving a consulting fee from ADMA Biologics, Inc. Dr Fitzgerald (collaborator) reports that, in the past, she received support as a coinvestigator on National Institutes of Health grant R43HD096961, and currently, she receives support as a coinvestigator on National Institutes of Health grant K23DK119463. Ms Wilson (collaborator) reports receiving travel reimbursements for conference presentations for the American Society of Pediatric Nephrology and receiving an award from the American Association of Critical Care Nurses in 2017; the other authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Heron M Deaths: leading causes for 2016. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67(6): 1–77 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, et al. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990–2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395(10219): 200–211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watson RS, Carcillo JA, Linde-Zwirble WT, Clermont G, Lidicker J, Angus DC. The epidemiology of severe sepsis in children in the United States. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167(5): 695–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Balamuth F, Weiss SL, Neuman MI, et al. Pediatric severe sepsis in U.S. children’s hospitals. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(9):798–805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ruth A, McCracken CE, Fortenberry JD, Hall M, Simon HK, Hebbar KB. Pediatric severe sepsis: current trends and outcomes from the Pediatric Health Information Systems database. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(9):828–838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hartman ME, Linde-Zwirble WT, Angus DC, Watson RS. Trends in the epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2013; 14(7):686–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fleischmann-Struzek C, Goldfarb DM, Schlattmann P, Schlapbach LJ, Reinhart K, Kissoon N. The global burden of paediatric and neonatal sepsis: a systematic review. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(3):223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weiss SL, Fitzgerald JC, Pappachan J, et al. ; Sepsis Prevalence, Outcomes, and Therapies Study Investigators and Pediatric Acute Lung Injury and Sepsis Investigators Network. Global epidemiology of pediatric severe sepsis: the sepsis prevalence, outcomes, and therapies study. [published correction appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(2): 223–224]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191(10):1147–1157 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brierley J, Carcillo JA, Choong K, et al. Clinical practice parameters for hemodynamic support of pediatric and neonatal septic shock: 2007 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine [published correction appears in Crit Care Med. 2009;37(4): 1536]. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(2): 666–688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kleinman ME, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM, et al. ; American Heart Association. Pediatric advanced life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/126/5/e1361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. ; Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013; 41(2):580–637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis AL, Carcillo JA, Aneja RK, et al. American college of critical care medicine clinical practice parameters for hemodynamic support of pediatric and neonatal septic shock [published correction appears in Crit Care Med. 2017;45(9):e993]. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45(6):1061–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(3):486–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen GY, Mecham N, Greenberg R. An emergency department septic shock protocol and care guideline for children initiated at triage. Pediatrics. 2011; 127(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/127/6/e1585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cruz AT, Perry AM, Williams EA, Graf JM, Wuestner ER, Patel B. Implementation of goal-directed therapy for children with suspected sepsis in the emergency department. Pediatrics. 2011;127(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/127/3/e758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Paul R, Neuman MI, Monuteaux MC, Melendez E. Adherence to PALS sepsis guidelines and hospital length of stay. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/130/2/e273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paul R, Melendez E, Stack A, Capraro A, Monuteaux M, Neuman MI. Improving adherence to PALS septic shock guidelines. Pediatrics. 2014;133(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/5/e1358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paul R, Melendez E, Wathen B, et al. A quality improvement collaborative for pediatric sepsis: lessons learned. Pediatr Qual Saf. 2017;3(1):e051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hershey TB, Kahn JM. State sepsis mandates - a new era for regulation of hospital quality. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(24):2311–2313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Evans IVR, Phillips GS, Alpern ER, et al. Association between the New York sepsis care mandate and in-hospital mortality for pediatric sepsis. JAMA. 2018;320(4):358–367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Britto MT, Fuller SC, Kaplan HC, et al. Using a network organisational architecture to support the development of Learning Healthcare Systems. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(11): 937–946 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clauss SB, Anderson JB, Lannon C, et al. Quality improvement through collaboration: the National Pediatric Quality improvement Collaborative initiative. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2015;27(5): 555–562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes LW, Dobyns EL, DiGiovine B, et al. A multicenter collaborative approach to reducing pediatric codes outside the ICU [published correction appears in Pediatrics. 2012;130(1):168–169]. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3) Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/129/3/e785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lyren A, Brilli R, Bird M, Lashutka N, Muething S. Ohio children’s hospitals’ solutions for patient safety: a framework for pediatric patient safety improvement. J Healthc Qual. 2016;38(4):213–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lyren A, Brilli RJ, Zieker K, Marino M, Muething S, Sharek PJ. Children’s hospitals’ solutions for patient safety collaborative impact on hospital-acquired harm. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3): e20163494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miller MR, Niedner MF, Huskins WC, et al. ; National Association of Children’s Hospitals and Related Institutions Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infection Quality Transformation Teams. Reducing PICU central line-associated bloodstream infections: 3-year results. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/128/5/e1077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A; International Consensus Conference on Pediatric Sepsis. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction in pediatrics. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(1):2–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brilli RJ, Goldstein B. Pediatric sepsis definitions: past, present, and future. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6(suppl 3): S6–S8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott HF, Brilli RJ, Paul R, et al. ; Improving Pediatric Sepsis Outcomes (IPSO) Collaborative Investigators.. Evaluating pediatric sepsis definitions designed for electronic health record extraction and multicenter quality improvement. Crit Care Med. 2020; 48(10):e916–e926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiss SL, Peters MJ, Alhazzani W, et al. Executive summary: surviving sepsis campaign international guidelines for the management of septic shock and sepsis-associated organ dysfunction in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020; 21(2):186–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weiss SL, Peters MJ, Alhazzani W, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign international guidelines for the management of septic shock and sepsis-associated organ dysfunction in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2020; 21(2):e52–e106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.