Abstract

Background:

Amyloid- β42 (Aβ42) is associated with plaque formation in the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Studies have suggested the potential utility of plasma Aβ42 levels in the diagnosis, and in longitudinal study of AD pathology. Conventional ELISAs are used to measure Aβ42 levels in plasma but are not sensitive enough to quantitate low levels. Although ultrasensitive assays like single molecule array or immunoprecipitation-mass spectrometry have been developed to quantitate plasma Aβ42 levels, the high cost of instruments and reagents limit their use.

Objective:

We hypothesized that a sensitive and cost-effective chemiluminescence (CL) immunoassay could be developed to detect low Aβ42 levels in human plasma.

Methods:

We developed a sandwich ELISA using high affinity rabbit monoclonal antibody specific to Aβ42. The sensitivity of the assay was increased using CL substrate to quantitate low levels of Aβ42 in plasma. We examined the levels in plasma from 13 AD, 25 Down syndrome (DS), and 50 elderly controls.

Results:

The measurement range of the assay was 0.25 to 500 pg/ml. The limit of detection was 1 pg/ml. All AD, DS, and 45 of 50 control plasma showed measurable Aβ42 levels.

Conclusion:

This assay detects low levels of Aβ42 in plasma and does not need any expensive equipment or reagents. It offers a preferred alternative to ultrasensitive assays. Since the antibodies, peptide, and substrate are commercially available, the assay is well suited for academic or diagnostic laboratories, and has a potential for the diagnosis of AD or in clinical trials.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid-β 1-42 (Aβ42) peptide, chemiluminescence, ELISA, plasma, rabbit monoclonal antibody (RabmAb) to Aβ42, sensitive and cost-effective method

INTRODUCTION

As the population of patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) continues to rise, the need for reliable biomarkers to support early diagnosis of AD, and to follow disease activity becomes more critical [1]. One of the neuropathologic lesions in AD is cerebral neuritic plaques. The core protein of the neuritic plaques is the 4 kDa amyloid-β peptide (Aβ]) that is proteolytically cleaved from the amyloid-β protein precursor, by β-, γ-, and other secretases [2]. Currently, the most useful biomarkers to diagnose AD include cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that shows low levels of Aβ42 peptide, with high levels of tau or phosphotau, and positron emission tomography (PET) for measurement of brain Aβ load using Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) [3, 4]. However, these methods cannot be used for broad population screening. Lumbar puncture is an invasive test, while PET scan uses radiation, is very expensive, and is only accessible in major medical centers. In contrast, blood-based biomarkers are minimally invasive, and more cost-effective than PET scan [5, 6]. There is a great deal of interest in developing blood-based biomarkers that could predict cerebral β-amyloidosis in AD or in persons with Down syndrome (DS) (35 years and older) [7, 8]. They are known to have increased risk of developing AD neuropathology and to have higher Aβ40 and Aβ42 levels in plasma [9, 10].

Emerging evidence suggests that various clearance mechanisms of Aβ peptide from the brain lead to about 100-fold lower concentrations in blood than in CSF [11]. Therefore, highly sensitive assays are needed to measure the low levels of β peptides in plasma. Numerous key publications advocate the utility of plasma Aβ42 levels in either predicting cerebral β-amyloidosis or response to therapy in AD [12–17].

Investigators quantitated Aβ42 levels in AD and control plasma using conventional ELISA [18–22], and Luminex xMAP technique [23–27]. However, results have been conflicting [14, 17]. Expressing the data in terms of Aβ40/Aβ42 ratio in plasma did not yield consistent findings [21]. The differences could be due to use of different analytical platforms, and specificity and affinity of antibodies or lack of sensitivity in assay methods [19–21].

High precision assays such as immunoprecipitation and liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (IP-MS) [17, 28], single molecule array (SIMOA) [29–31], and immunomagnetic reduction (IMR) assay [32, 33] are sensitive enough to quantitate low levels of Aβ42 in plasma. However, they need expensive equipment, and reagent kits or are laborious, and thus limit their use at many academic institutions or commercial diagnostic laboratories.

To improve the sensitivity of sandwich ELISA to quantitate the low levels of Aβ42 in plasma, studies have documented that the assay needs high affinity antibodies [34, 35]. However, they are not readily available. We have generated and characterized high affinity rabbit monoclonal antibody (RabmAb) specific to Aβ42, which is available commercially [34]. Since this antibody possesses high affinity, it allows the quantification of Aβ42 in the presence of at least 100-fold excess of Aβ40. Chemiluminescence (CL) based sandwich ELISA is highly sensitive, easy to use, and does not need any expensive equipment. It has demonstrated the ability to quantitate low levels of peptide using super signal ELISA femto substrate in the femtogram range with increased precision compared to conventional ELISA [36]. The detection can be performed using a simple spectrofluorometer. This makes it cost-effective, and practical to use in academic or commercial diagnostic laboratories. The assay could be implemented anywhere, and could be used to support the clinical diagnosis of AD, or in selection of clinical trials. It provides a better alternative to newly developed ultrasensitive assays.

The present study tested the hypothesis that this sensitive and cost-effective ELISA assay could quantitate low levels of Aβ42 in plasma. We measured the levels in AD, DS, and control plasma.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Peptide and antibodies

Purified Aβ42 peptide used as a standard in ELISA was obtained from Bachem (King of Prussia, PA). The purity of peptide was between 92 to 95% as examined by high performance liquid chromatography. A vial containing one mg of peptide was solubilized in one ml of hexafluoroisoproponal (Thomas Scientific, Swedesboro, NJ). There was no peptide solubility issue observed during reconstitution. 15 μl of the peptide was aliquoted per polypropylene tube, and stored at −80°C until further use.

Two monoclonal antibodies were used to develop the sandwich ELISA: 1) mouse monoclonal antibody (mousemAb), clone 6E10 specific to an epitope present on 3–11 amino acid residues of Aβ peptide (capture antibody), and RabmAb specific to Aβ42, clone 1-11-4 to an epitope present on 33–42 amino acid residue (detecting antibody) β. Both antibodies were generated in our Institute, and well characterized as described previously. They are commercially available from BioLegend, San Diego, CA., and have been widely used by AD researchers. The specificity of the antisera was examined using inhibition ELISA assay, immunoblotting, and immunohistochemical methods [34]. The RabmAb to Aβ42 possesses high affinity to Aβ42 with dissociation constant (KD) for the antibody of 0.7 nM [34].

Quantitation of Aβ42 levels in plasma using ELISA

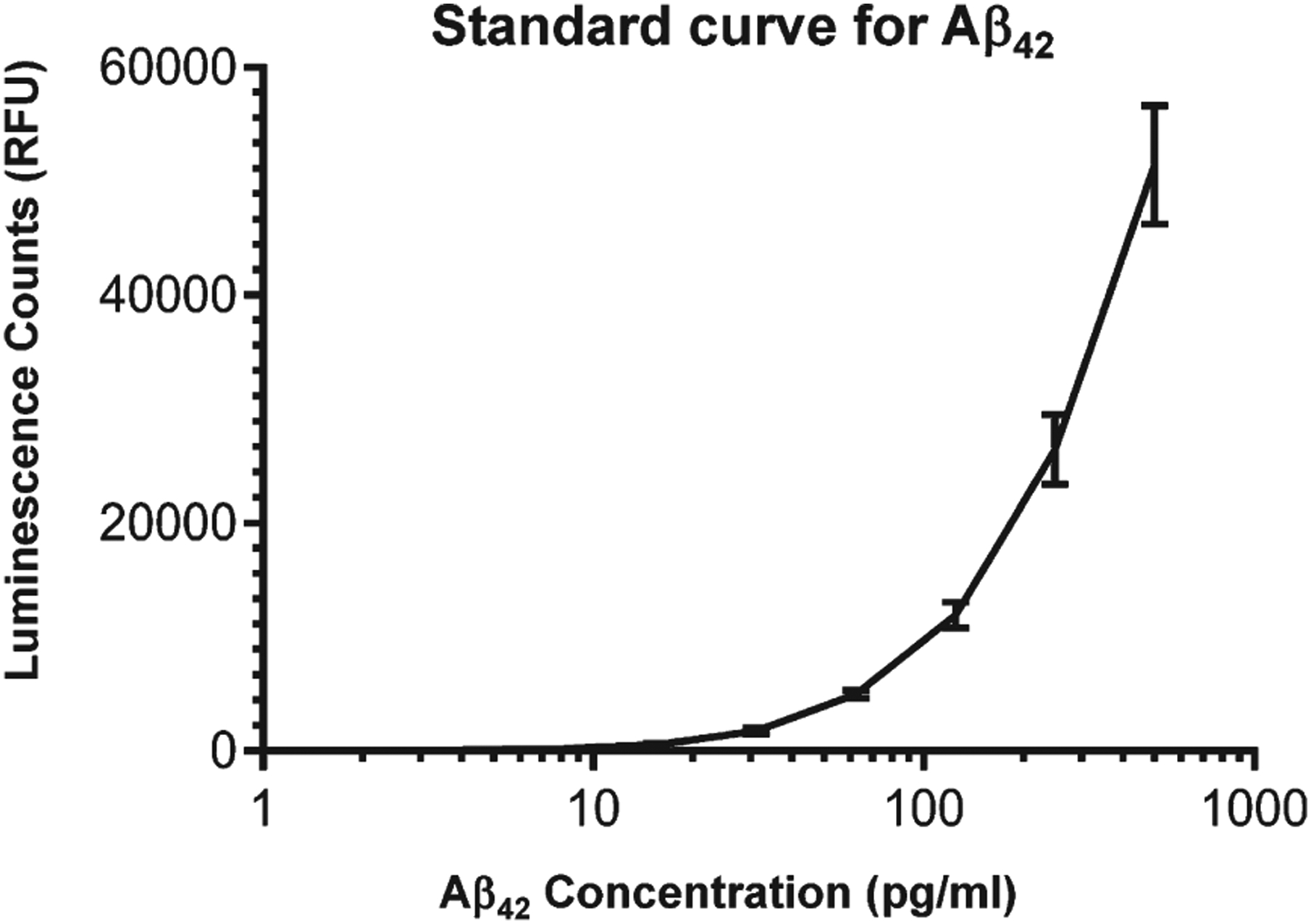

Ninety-six wells of white opaque microtiter plates (Nunc FluoroNunc/LumiNunc, Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) were coated with 100 μl of 2.5 μg/ml of mousemAb, clone 6E10 in 0.05 M carbonate bicarbonate buffer, pH 9.6. These plates provide the best signal to noise ratio. Plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. Then plates were washed with 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.2 + 0.05% Tween-20 (PBST), and blocked for 1 h at room temperature with PBST+1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Plates were washed thrice, and 100 μl of Aβ42 peptide as a standard was added in the range from 500 pg/ml to 0.25 pg/ml diluted in PBST+1% BSA. Plasma (diluted 1:2) was added in additional rows. Two duplicate rows of standards were used. Plates were kept at room temperature for 2 h, and incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed, and 100 μl of 0.2 μg/ml of RabmAb to Aβ42 were added, and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. Then plates were washed, and 100 μl of goat anti-rabbit IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (HRP) (diluted 1:100,000 in PBST) (Invitrogen, Rockford, IL) were added to the wells, and kept at room temperature for 2 h. They were further washed, and the reaction was developed with super signal ELISA femto maximum sensitivity substrate specific for HRP according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Plates were gently stirred for two min and the signal for each well was read at emission 425 nm according to the kit instructions using a Biotech Synergy H1 Hybrid Reader. The relationship between the counts and Aβ42 concentration was determined using a 4 features logistic logarithm function. Nonlinear curve fitting was performed with a commercially available program (Biotek Instruments, Winooski, VT) to convert the counts into relative fluorescence units (RFU) of plasma to estimated protein concentration. A calibration curve ranging from 500 pg/ml to 0.25 pg/ml was constructed to determine Aβ42 levels in the samples (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Standard curve for the Aβ42 assay. Results are expressed as the mean ± SD of 4 individual standard curves.

Collection of plasma samples

Plasma from N= 13 patients with probable AD (75±9 years of age), and 25 elderly controls (71±9 years of age) with no history of dementia were received from the Alzheimer Disease Research Center, NY University School of Medicine, NY. Plasma from N= 25 individuals with DS (46±9 years of age), and 25 young controls (45±7 years of age) with no history of neurological diseases were received from Dr. A.J. Dalton, Institute for Basic Research, Staten Island, NY. Aliquots of all samples collected previously were stored frozen at −80°C. All samples were coded during the analytical procedure.

Statistical analysis

The analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 software program. The groups were compared with each constituent, using the Mann-Whitney or Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. Pearson’s correlation with Bonferroni correction was used to analyze the relationship between the variables. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Reproducibility of the standard curve

Figure 1 shows the average of 10 consecutive standard curves in the range of 0.25 to 500 pg/ml by expressing luminescence counts obtained for each calibrant (Table 1). The correlations among individual standard curves showed a high degree of linearity within each assay (R2 = 0.92).

Table 1.

Aβ42 concentrations and luminescence counts Plasma Aβ42 levels in AD, DS, and controls

| Aβ42 (pg/ml) | Counts | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | |

| 500 | 51,412 | 5,227 |

| 250 | 26,416 | 3,041 |

| 125 | 11,946 | 1,177 |

| 62.5 | 4,950 | 356 |

| 31.2 | 1,723 | 261 |

| 15.6 | 522 | 94 |

| 7.8 | 160 | 36 |

| 3.9 | 93 | 25 |

| 1.95 | 41 | 16 |

| 0.97 | 15 | 9 |

Precision

Reproducibility (intra-assay variability) and repeatability (inter-assay variability) of the assay was evaluated with plasma samples. In four independent samples of plasma, the mean coefficients of variation (CV) of duplicates (intra-assay precision) were on average 8%, and between-assay variation on average was 10.5%.

Analytical sensitivity

Sensitivity (lowest standard above blank) was calculated as blank signal plus two standard deviations (SD) from 10 assays. The lower limit of quantitation was 3.0 pg/ml (Fig. 2). The limit of detection (same with a signal significantly different from blank) was1.0 pg/ml (p < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Lower Limit of Quantification: Triplicate measurements of serially diluted calibrator read on the calibration curve.

Stability

We tested the stability of plasma at 4°C, and compared this to samples stored at −80°C. Three aliquoted plasma samples frozen at −80°C were thawed on day 1, and stored for 4 days at 4°C until analysis. There was no significant change in signal in samples stored at day 1 and day 4 at 4°C (p = 0.7).

Three plasma samples were analyzed for stability during freeze-thawing cycles. The samples underwent 1, and 2 freeze-thawing cycles and the signal was normalized to the sample freeze-thawed once. There was no significant effect of freeze-thawing on the measured signals (2 freeze-thawing cycles: p = 0.6).

Assay specificity

The specificity of the assay was examined by coating the wells of microtiter plates with 6E10, and incubated these wells with Aβ42 in the usual manner. Half of these wells were treated with RabmAb to Aβ42, and the other half with equivalent amount of RabmAb to either Aβ40 or normal rabbit IgG. Wells were developed with super signal ELISA femto substrate as described earlier. Our data showed that wells with RabmAb to Aβ42 showed luminescence counts as expected. However, wells with RabmAb to Aβ40 or normal rabbit IgG showed no measurable counts.

Quantitation of Aβ42 in plasma

Levels of Aβ42 in plasma from AD, elderly controls, DS and young controls are given in Table 2. Levels were measurable in all AD, DS, and 45 of 50 controls plasma. The levels were higher in AD than in the controls (p < 0.05), and also higher in DS than controls (p < 0.01). The findings are consistent with our previous studies [37]. There was no association of age with Aβ42 levels in either group.

Table 2.

Plasma Aβ42 levels in AD, DS, and controls

| Group | No. | Age in years Mean ± SD | Aβ42 (pg/ml) Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD | 13 | 75 ± 9 | 25.8 ± 55.9 |

| Nondemented old controls | 25 | 71 ± 9 | 5.9 ± 5.1 |

| DS | 25 | 46 ± 9 | 81.5 ± 81.6 |

| Nondemented young controls | 25 | 45 ± 7 | 13.8 ± 19.1 |

Compared with nondemented old controls; p < 0.0.5. Compared with nondemented young controls; p < 0.01.

Comparison of CL based ELISA with ultrasensitive assays

Our assay was compared with different assays in terms of sensitivity, and Aβ42 levels in plasma (Table 3). Ultrasensitive assays are highly sensitive than ELISA for determining Aβ42 in plasma. Since the ELISA used here is an-house ELISA, it was difficult to estimate the cost per sample. Our assay is expected to have greatly decreased cost, but be able to quantitate low levels.

Table 3.

Comparison of CL based ELISA and ultrasensitive assays

| Assay Sensitivity | CL based ELISA | Simoa | IMR |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOD (pg/ml) | 1 | 0.12–0.3 | NA |

| LLOQ (pg/ml) | 3 | 1.2 | 1–2 |

| Plasma Aβ42 (pg/ml) range | 10–20 | 15–18 | 13–19 |

DISCUSSION

In the present study we have developed a minimally invasive, sensitive, and cost-effective sandwich ELISA to quantitate low levels of Aβ42 in plasma. The assay has important implications for screening and diagnosis of AD, for clinical trials or prediction of conversion from preclinical AD to mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and MCI to AD, and for general population screening.

The combination of a high affinity RabmAb specific to Aβ42, and enhanced CL based assay kit allows more sensitive detection of Aβ42. Our data showed that the assay is superior in sensitivity over our previously published data [19] using conventional ELISA, and is able to detect levels in plasma as low as 1 pg/ml. The assay is relatively simple, easy to use, and does not need any expensive reagents or equipment, compared to the high cost of newly developed ultrasensitive assays. Since the reagents used in this assay are commercially available, it might also offer a measure of consistency if other scientists were to use the same method. It is practical for examining a small number of plasma samples or in pilot clinical studies for investigators in academic institutions.

We have selectively used the concentrations of capture and detection antibodies to recognize different Aβ epitopes, and optimized assay conditions. Although it is ideal to use the same batch of reagents for the samples in the project, it is difficult to meet these conditions with a large number of samples. Since the assay performance can be influenced by batch-to-batch variation or accuracy of pipetting, we ran peptide standards and control samples in duplicate on every plate. Levels of control samples quantitated during the sample analysis were within expected ranges. Thus using internal quality control, we monitored and corrected deficiencies in day to day run. The data showed that the intra-assay and inter-assay variability were slightly higher but still within the line of ultrasensitive assays. Our findings contribute to the growing body of new sensitive assays developed to quantitate Aβ42 levels in plasma.

Our ELISA data showed that levels of plasma Aβ42 were higher in AD than control. The results are consistent with studies published previously [19, 33, 34]. In contrast, others have shown that the levels were lower or similar in AD than controls [18, 20, 22, 24–27]. The reasons for the inconsistency are multiple. These included: age, apolipoprotein E genotype, disease severity, use of different analytical platforms, variability of reagents, specificity and affinity of antibodies, sensitivity in assay method, heterogeneous study design, differences in follow-up duration, etc.[38]. Future studies are needed to replicate the differences among the published studies to resolve the issue regarding the increase or decrease of plasma Aβ42 levels in AD.

A review of recent literature [38] showed that a majority of investigators measured plasma Aβ42 levels in free or soluble form. One possible explanation for these conflicting data is that fibrils or aggregates might exist in AD plasma or that the Aβ42 is in complex with other proteins, so that the total amount of Aβ42 measured might have been underestimated. The Aβ42 we used in our ELISA was initially dissociated with hexafluoroisoproponal (HFIP). However, we did not treat plasma samples with HFIP. We do not know whether the C-terminal epitopes in the fibrils are all exposed so that they can all bind to the antibodies. The latter might account for higher plasma Aβ42 levels in AD than control. This is an interesting question, but beyond the scope of our paper, which is to develop a sensitive and cost-effective assay to quantitate Aβ42 levels in plasma.

In addition to ELISA, there is another multiplex assay, namely Meso Scale Delivery (MSD) based on electrochemiluminescence. This was mainly used to quantitate CSF Aβ peptides [39]. Although the method is more sensitive than conventional ELISA or Luminex xMAP method, the studies using MSD to measure Aβ42 levels in plasma are limited [40]. Our preliminary studies using MSD platform showed that the absolute concentrations of plasma Aβ levels varied considerably when compared with ELISA[40]. The reasons for this may include the differences in the affinities of antibodies, or purity and source of Aβ peptides used as standards. The assay is not in widespread use to quantitate plasma Aβ levels because of the high cost of equipment, and reagents.

Ultrasensitive or high precision assays have been proposed to quantitate Aβ42 levels in plasma. They include: SIMOA, IP-MS, IMR, stable isotope labeling kinetics [41], among others. However, there are just a few studies published on the measurement of Aβ40 or Aβ42 levels using SIMOA or IP-MS assays. The data showed a good correlation of plasma Aβ42 levels or the ratio of Aβ40/Aβ42 with brain Aβ load deposition detected by PiB-PET scans. Although these methods are sensitive to diagnose AD, their widespread use is limited, since they are laborious, enormously expensive, difficult to standardize, and not easily accessible. In addition, a number of these assays need thorough validation before their potential usefulness either in diagnosis of AD or clinical trials [33].

There are several major strengths of our study. First, use of a high affinity RabmAb to Aβ42 rather than a mousemAb to Aβ42. Our antibody gives the highest level of consistency between batches, and has the ability to use at a higher dilution (5 to 10 times average) than mousemAb to Aβ42 in ELISA with little or no background. Since in the present study, levels of Aβ42 in a majority of AD, DS, and controls plasma are >7.8 pg/ml, our method shows a sufficient limit of detection well within the range of 10 to 20 pg/ml found in ultrasensitive assays (Table 2). Second, since the reagents of the assay we developed are commercially available, it is well suited for widespread use for researchers in academic institutions, and clinical diagnostic laboratories. Third, the assay is more cost-effective than ultrasensitive assays, since it does not need any start up high cost equipment or reagents.

There are several limitations to the study: First, the sample size was small, and no clinical data was included. The study did not include any longitudinal data, since the aim of the study was to determine whether we could develop a sensitive assay to detect low levels of Aβ42 in plasma. Second, we did not extend our findings to examine the correlation of plasma Aβ42 levels in individuals diagnosed with probable AD, and compared with those of CSF Aβ42, and Aβ load using PiB. This is an important area for further study. Third, the quantitation of plasma Aβ42 data was not compared with either SIMOA or IP-MS methods. This needs to be assessed in larger cohorts, and will be the subject of future studies. Fourth, the analytic performance of the assay lacked an external validation.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, the present study is the first report describing a sensitive, minimally invasive, and cost-effective assay to quantitate low levels of Aβ42 in plasma. It could be useful in both clinical and research settings not only in the study of AD or decline of cognition in elderly persons with DS, but it also offers potential in AD animal model studies. The method requires replication in an independent cohort, and thorough validation in multicenter studies. Longitudinal studies with a larger number of samples are warranted before the assay becomes part of the routine clinical use. A standardized kit for automated quantitation of plasma Aβ42 is possible in the future.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The work was supported by funds provided by New York State through its office of People with Developmental Disabilities and grants support to T. Wisniewski, from P30 AG066512 and PO1 AG0 60882.

Footnotes

Authors’ disclosures available online (https://www.j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/20-0861r1).

REFERENCES

- [1].Jack CR Jr., Bennett DA, Blennow K, Carrillo MC, Dunn B, Haeberlein SB, Holtzman DM, Jagust W, Jessen F, Karlawish J, Liu E, Molinuevo JL, Montine T, Phelps C, Rankin KP, Rowe CC, Scheltens P, Siemers E, Snyder HM, Sperling R (2018) Contributors NIA-AA Research Framework: Toward a biological definition of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 14, 535–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Soria Lopez JA, Gonzalez HM, Legar GC (2019) Alzheimer disease. Handb Clin Neurol 167, 231–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hansson O, Seibyl J, Stomrud E, Zetterberg H, Trojanowski JQ, Bittner T, Lifke V, Corradini V, Eichenlaub U, Batrla R, Buck K, Zink K, Rabe C, Blennow K, Shaw LM, Swedish BioFINDER study group; Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (2018) CSF biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease concord with amyloid-beta PET and predict clinical progression: A study of fully automated immunoassays in BioFINDER and ADNI cohorts. Alzheimers Dement 14, 1470–1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Molinuevo JL, Ayton S, Batrla R, Bedner MM, Bittner T, Cummings J, Fagan AM, Hampel H, Mielke MM, Mikulskis A, Obrayant S, Scheltens P, Sevigny J, Shaw LM, Soares HD, Tong G, Troajanowski JQ, Zetterberg H, Blennow K (2018) Current state of Alzheimer’s fluid biomarkers. Acta Neuropathol 136, 821–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Paraskevaidi M, Allsop D, Karim S, Martin FL, Crean S (2020) Diagnostic biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease using noninvasive specimens. J Clin Med 9, 167–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Hampel H, O’Bryant S, Molinuevo J, Zetterberg H, Masters CL, Lista S, Kiddle SJ, Batria R, Blennow K (2018) Blood-based biomarkers for Alzheimer disease: Mapping the road to the clinic. Nat Rev Neurol 11, 639–652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Blennow K, Zetterberg H (2018) Biomarkers for Alzheimer disease: Current status and prospects for the future. J Int Med 284, 643–663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Blennow K (2017) A review of fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer disease: Moving from CSF to blood. Neurol Ther 6, S15–S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Zammit MD, Laymon CM, Betthauser TJ, Cody KA, Tudorascu DL, Minhas DS, Johnson SC, Handen BL, Sabbagh MN, Zaman SH, Mathis CA, Klunk WE, Cohen AD, Bradley TC (2020) Amyloid accumulation in Down syndrome measured with amyloid load. Alzheimer Dement 12, e12020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schupf N, Zigman W, Tong MX, Pang D, Mayuex R, Mehta PD, Silverman W (2010) Change in plasma Aβ peptides and onset of dementia in adults with Down syndrome. Neurology 75, 1639–1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Tarasoff-Conway JM, Carare RO, Osorio RS, Glodzik L, Butler T, Fieremans E, Axel L, Rusinek H, Nicholson C, Zlokovic BV, Frangione B, Blennow K, Menard J, Zetterberg H, Wisniewski T, de Leon MJ (2015) Clearance systems in the brain-implications for Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol 11, 457–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].de Rojas I, Romero J, Rodriguez-Gomez O, Pesini P, Sanabria A, Perez-Cordon A, Abdelnour C, Hernandez I, Rosende-Roca M, Mauleon A, Vargas L, Alegret M, Espinosa A, Ortega G, Gil S, Guitart M, Gailhajanet A, Santos-Santos MA, Moreno-Grau S, Sotolongo-Grau O, Ruiz S, Montrreal L, Martin E, Peleja E, Lomena F, Campos F, Vivas A, Gomez-Chiari M, Tejero MA, Gimenez J, Perez-Grijalba V, Marquie GM, Monte-Rubio G, Valero S, Orellana A, Tarraga L, Sarasa M, Ruiz A, Boada M, FACE-HBI study (2018) Correlations between plasma and PET beta-amyloid levels in individuals with subjective cognitive decline: The Fundacio ACE Healthy Brain Initiative (FACEHBI). Alzheimers Res Ther 10, 1–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chatterjee P, Elmi M, Goozee K, Shah T, Sohrabi HR, Dias CB, Pedrini S, Shen K, Asih PR, Dave P, Taddei K, Vanderstichele H, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Martins RN (2019) Ultrasensitive detection of plasma amyloid-beta as a biomarker for cognitively normal elderly individuals at risk of Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis 71, 775–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fandos N, Perez-Grijalba V, Pesini P, Olmos S, Bossa M, Villemagne VL, Doecke J, Fowler C, Masters CL, Sarasa M, AIBL Research Group (2017) Plasma amyloid beta 42/40 ratios as biomarkers for amyloid beta cerebral deposition in cognitively normal individuals. Alzheimers Dement (Amst) 8, 179–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Vergallo A, Megret L, Lista S, Cavedo E, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Vanmechelen E, De Vos A, Habert MO, Potier MC, Dubois B, Neri C, Hampel H, INSIGHT-preAD study group; Alzheimer Precision Medicine Initiative (APMI) (2019) Plasma amyloid beta 40/42 ratio predicts cerebral amyloidosis in cognitively normal individuals at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 15, 764–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Albani D, Marizzoni M, Ferrari C, Fusco F, Boeri L, Raimondi I, Jovichih J, Babiloni C, Soricelli A, Lzio R, Galluzi S and Pharma Cog consortium (2019) Plasma Aβ42 as biomarker of prodromal Alzheimer disease progression in patients with amnestic mild cognitive impairment: Evidence from the phrmacog/E –ADNI study. J Alzheimers Dis 69, 37–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Nakamura A, Kaneko N, Villemagne VL, Kato T, Doecke J, Dore V, Fowler C, Li QX, Martins R, Rowe C, Tomita T, Matsuzaki K, Ishii K, Ishii K, Arahata Y, Iwamoto S, Ito K, Tanaka K, Masters CL, Yanagisawa K (2018) High performance plasma amyloid-beta biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease. Nature 554, 249–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Kleinschmidt M, Schoenfeld R, Gottlich C, Bittner D, Metzner JE, Leplow B, Demuth HU (2016) Characterizing aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia with blood-based biomarkers and neuropsychology. J Alzheimers Dis 50, 111–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Schupf N, Tang MX, Fukuyama H, Manly J, Andrews H, Mehta P, Ravetch J, Mayeux R (2008) Peripheral Aβ subspecies as risk biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 14052–14057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Olsson B, Lautner R, Andreasson U, Ohrfelt A, Portelius E, Bjerke M, Holtta M, Rosen C, Olsson C, Strobel G, Wu E, Dakin K, Petzold M, Blennow K, Zetterberg H (2016) CSF and blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol 15, 673–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Wang J, Qiao F, Shang S, Li P, Chen C, Dang L, Jiang Y, Huo K, Deng M, Wang J, Qu Q (2018) Elevation of plasma amyloid-beta level is more significant in early stage of cognitive impairment: A population-based cross-sectional study. J Alzheimers Dis 64, 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Hillal S, Wolters FJ, Verbeek M, Vanderstichele H, Ikram MK, Stoops E, Ikram MA, Vernooij MW (2018) Plasma amyloid β levels, cerebral atrophy, and risk of dementia: A population based study. Alzheimers Res Ther 10, 63–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Chouraki V, Beiser A, Younkin L, Preis SR, Weinstein G, Hansson O, Skoog I, Lambert JC, Au R, Launer L, Wolf PA, Younkin S, Seshadri S (2015) Plasma amyloid-beta and risk of Alzheimer’s disease in the Framingham Heart Study. Alzheimers Dement 11, 249–257 e241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Rembach A, Faux NG, Watt AD, Pertile KK, Rumble RL, Trounson BO, Fowler CJ, Roberts BR, Perez KA, Li QX, Laws SM, Taddei K, Rainey-Smith S, Robertson JS, Vandijck M, Vanderstichele H, Barnham KJ, Ellis KA, Szoeke C, Macaulay L, Rowe CC, Villemagne VL, Ames D, Martins RN, Bush AI, Masters CL, AIBL research group (2014) Changes in plasma amyloid beta in a longitudinal study of aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement 10, 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Hanon O, Vidal JS, Lehmann S, Bombois S, Allinquant B, Treluyer JM, Gele P, Delmaire C, Blanc F, Mangin JF, Buee L, Touchon J, Hugon J, Vellas B, Galbrun E, Benetos A, Berrut G, Paillaud E, Wallon D, Castelnovo G, Volpe-Gillot L, Paccalin M, Robert PH, Godefroy O, Dantoine T, Camus V, Belmin J, Vandel P, Novella JL, Duron E, Rigaud AS, Schraen-Maschke S, Gabelle A, BALTAZAR study group (2018) Plasma amyloid levels within the Alzheimer’s process and correlations with central biomarkers. Alzheimers Dement 14, 858–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Yaffe K, Weston A, Graff-Radford NR, Satterfield S, Simonsick EM, Younkin SG, Younkin LH, Kuller L, Ayonayon HN, Ding J, Harris TB (2011) Association of plasma beta-amyloid level and cognitive reserve with subsequent cognitive decline. JAMA 305, 261–266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hansson O, Stomrud E, Vanmechelen E, Ostling S, Gustafson DR, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Skoog I (2012) Evaluation of plasma Aβ as predictor of Alzheimer’s disease in older individuals without dementia: A population-based study. J Alzheimers Dis 28, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schindler SE, Bollinger JG, Ovod V, Mawuenyega KG, Li Y, Gordon BA, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Benzinger TLS, Xiong C, Fagan AM, Bateman RJ (2019) High-precision plasma β-amyloid 42/40 predicts current and future brain amyloidosis. Neurology 93, e1647–e1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Janelidze S, Stomrud E, Palmqvist S, Zetterberg H, van Westen D, Jeromin A, Song L, Hanlon D, Tan Hehir CA, Baker D, Blennow K, Hansson O (2016) Plasma β-amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease and vascular disease. Sci Rep 6, 26801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Verberk IMW, Slot RE, Verfaillie SCJ, Heijst H, Prins ND, van Berckel BNM, Scheltens P, Teunissen CE, van der Flier WM (2018) Plasma amyloid as prescreener for the earliest Alzheimer pathological changes. Ann Neurol 84, 648–658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Song L, Lachno DR, Hanlon D, Shepro A, Jeromin A, Gemani D, Talbot JA, Racke MM, Dage JL, Dean RA (2016) A digital ELISA for ultrasensitive measurement of amyloid β 1–42 peptide in human plasma with utility for studies of Alzheimer’s disease therapeutics. Alzheimers Res Ther 8, 58–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Chen TB, Lee YJ, Lin SY, Chen JP, Hu CJ, Wang PN, Cheng I. (2019) Plasma Aβ42 and total tau predict cognitive decline in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Nature 9, 13894–13907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Lue LF, Guerra A, Walker DG (2017) Amyloid β and tau as Alzheimer disease blood biomarkers: Promise from new technologies. Neurol Ther 6, S25–S36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Miller DL, Potempska A, Weigel J, Mehta PD (2011) High-affinity rabbit monoclonal antibodies specific for amyloid peptides Aβ40 and Aβ42. J Alzheimers Dis 23, 293–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Miller DL, Potempska A, Mehta PD (2007) Humoral immune response to peptides derived from the beta-amyloid peptide C-terminal sequence. Amyloid 14, 39–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kuhle J, Barro C, Andreasson U, Derfuss T, Lindberg R, Sandeluis A (2016) Comparison of three analytical platforms for quantitation of the neurofilament light chain in blood samples: Elisa, electrochemiluminescence immunoassay and Simoa. Clin Chem Lab Med 54, 1655–1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Mehta PD, Patrick BA, Barshatzsky M, Mehta SP, Frackowiak J, Mazur-Kolecka B, Miller DL (2015) Generation of rabbit monoclonal antibody to amyloid-β38: Increased plasma Aβ38 levels in Down syndrome. J Alzheimers Dis 46, 1021–1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Wang X, Sun Y, Li T, Cai Y, Han Y (2020) Amyloid β as a blood biomarker for Alzheimer disease: A review of recent literature. J Alzheimers Dis 73, 819–832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pan C, Kroff A, Galasko D, Ginghina C, Li G, Quinn J, Montine TJ, Cain K, Shi M, Zhang J (2015) Diagnostic values of CSF fluid t-tau and Aβ42 using meso scale discovery assays for Alzheimer disease. J Alzheimers Dis 45, 709–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Oh ES, Mielke MM, Rosenberg PP, Jain A, Fedarko NS, Lyketsos CG, Mehta PD (2010) Comparison of conventional ELISA with technology for detection of amyloid-β in plasma. J Alzheimers Dis 21, 769–773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Ovod V, Ramsey KN, Mawuenyega KG, Bollinger JG, Hicks T, Schneider T, Sullivan M, Paumier K, Holtzman DM, Morris JC, Benzinger T, Fagan AM, Patterson BW, Bateman RJ (2017) Amyloid β concentrations and stable isotope labeling kinetics of human plasma specific to central nervous system amyloidosis. Alzheimers Dement 13, 841–849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]