Abstract

Jewish Americans may grapple with issues of ethnic identity differently than the larger White American group. Drawn from a large multisite sample (N = 8,501), 280 Jewish American (207 female, 73 male) emerging adults were compared with White American and ethnic minority samples on ethnic and U.S. identity. Jewish Americans rated themselves as significantly higher on measures of ethnic and U.S. identity compared with White Americans but not as highly as ethnic minorities. Ethnic identity search, affirmation, and resolution also predicted higher self-esteem for Jewish Americans, similar to the pattern for other ethnic groups. In addition, ethnic identity search and affirmation moderated the link between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms among Jewish Americans.

Keywords: Ethnic identity, Jewish American, Jews, perceived discrimination, self-esteem, White

U.S. ethnic and racial identity research has primarily focused on the study of the four largest racial and ethnic minority groups: African Americans, Latin Americans, Asian Americans, and American Indians, usually in comparison with European-descent Whites (Schwartz et al., 2014). The White group, in most ethnic and racial identity research, is presumptively of European descent and represents a homogenous comparison group. However, this presumption ignores subgroups within the White group that may differ significantly on ethnic identity (See Koutrelakos, 2013; and Ponterotto et al., 2001; for notable exceptions). Jewish Americans may represent one such White American subgroup. Given that most U.S. Jews appear White to others (or choose to blend in as such), Jewish Americans may hold a unique position when it comes to ethnic identity: many may retain particular affiliations, values, and beliefs that are different from those of the mainstream White American population. Jews in the United States have experienced prejudice, discrimination, and exclusion, such as quotas and restrictions for jobs and college admissions, property covenants, and restriction on club memberships—restrictions that did not apply to most other White Americans. Given this history, Jewish Americans may develop ethnic identities differently from other White Americans and more like other ethnic minorities in some aspects.

Jewish Americans and ethnic identity

During their history in the United States, Jews have variously been considered a race, an ethnic group, members of a religion, and a culture (Brodkin, 1998; Hollinger, 2000). However, both sociologically and in common discourse, Jews have gradually become White over time (Brodkin, 1998). In most contemporary psychological research, Jews have been included within the categories of White, Caucasian, or Euroamerican. However, being Jewish American may represent membership in an ethnic group rather than a White subgroup. According to the American Psychological Association (2003), ethnicity refers to “the acceptance of group mores and practices of one’s culture of origin and the concomitant sense of belonging” (p. 380). This definition may apply to Jews because they have maintained a feeling of cohesion as a group and practice elements of their culture of origin (Koutrelakos, 2013; Kivisto & Nefzger, 1993). Given this retention of cultural practice, they too may grapple with the formation of an ethnic identity similarly to other ethnic groups.

A few studies on ethnic identity have specifically included Jewish Americans and focused on the experiences of Jewish adolescents and young adults. In one study, 219 high school juniors and seniors were asked to indicate their ethnic group membership (e.g., Jewish American or Irish American), and to complete the Multi-Group Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Roberts et al., 1999). There were significant differences among the three largest White ethnic groups, namely Jewish Americans, Irish Americans, and Italian Americans. Jewish Americans had the highest ethnic identity scores, and Irish Americans were lowest (Ponterotto, Gretchen, Utsey, Stracuzzi, & Saya, 2003). Markstrom, Berman, and Brusch (1998) found that Jewish adolescents (N = 102) residing in Jewish dominant neighborhoods around Toronto, Canada, scored higher in total ethnic identity on the MEIM and in participating in ethnic behaviors or practices than did those who resided in nondominant neighborhoods. Dubow, Pargament, Boxer, and Tarakeshwar (2000) surveyed 75 Jewish Sunday school students in the U.S. Midwest about ethnic identity, as assessed using the MEIM, and coping strategies. Ethnic identity was positively related to Jewish-oriented behaviors and practices and to ethnic-related stressors. Dubow and colleagues also found that ethnic identity was positively related to the use of ethnic-related coping strategies (e.g., seeking God’s direction and support, seeking cultural and social support, struggling spiritually), and concluded that ethnic identification might serve as a coping resource for Jewish youth. Davey, Eaker, Fish, and Klock (2003) found that, among the 63 U.S. Jewish participants in their sample, younger Jewish adolescents (ages 11 to 14 years) had higher feelings of affirmation and belonging on the MEIM than did an older group of Jewish adolescents (ages 15 to 18 years). In addition, Davey and colleagues found that ethnic identity was associated with scholastic competence. Kahn and Aronson (2012) found that Jewish emerging adult college students (N = 174) showed similar patterns of ethnic identity centrality and regard as did African American youth on an adapted version of the Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI; Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997). These studies indicate that ethnic identity does appear to be salient for young Jewish Americans.

Jewish Americans and U.S. identity

Although they may be viewed as an ethnic group, because of their perceived or chosen Whiteness, Jewish Americans may have access to aspects of U.S. identity that may not be available to other ethnic minorities. Jewish Americans may explore and feel a sense of belongingness and affirmation from their American identity more like White Americans than like people of color. Birman, Persky, and Chan (2010) found that Russian Jewish immigrant adolescents (N = 213) residing in the United States indicated higher American identity scores compared with their non-Jewish Russian émigré peers. For this study, we anticipated that Jewish Americans would rate themselves similarly to other White Americans on U.S. identity in contrast to other ethnic minorities, who may identify themselves less with being American (Devos & Mohamed, 2014).

Jewish American ethnic identity and psychosocial health

Accordingly, if Jewish Americans are viewed as an ethnic group, then they may have similar experiences as do other ethnic minorities in terms of developing an ethnic identity. Many previous studies have noted that African American, Latino, Asian American, and American Indian youth who have a strong sense of ethnic identity also report higher levels of self-esteem (Rivas-Drake et al., 2014; Smith & Silva, 2010; Syed & Azmitia, 2009). This relation may be supported by social identity theory (Tajfel & Turner, 1979) where individuals’ sense of belongingness and affiliation with a group may promote well-being from that affiliation. If Jewish Americans are like other ethnic minorities, they too might derive a boost in self-esteem from developing a strong ethnic identity. Whether this relationship between ethnic identity and self-esteem applies to Jewish Americans is unknown.

Similarly, past research on ethnic minorities has indicated that ethnic identity may offset the link between discrimination and poor mental health outcomes (Iturbide, Raffaelli, & Carlo, 2009). For example, Stein, Kiang, Supple, and Gonzalez (2014) found that, among Asian American adolescents, ethnic identity buffered the link between discrimination and depressive symptoms for those without economic stressors. Similarly, Syed and Juang (2014), across several samples of college students, found that ethnic identity commitment was associated with fewer depressive symptoms. Branscombe, Schmitt, and Harvey (1999) have described the buffering of deleterious outcomes as a rejection-identification effect. That is, experiencing discrimination for ethnic minorities may prompt stronger ethnic group affiliation and identification, which then promotes better psychological functioning. For Jewish Americans, the same may be true. In light of perceived discrimination, a sense of Jewish ethnic identity may reduce poor mental health outcomes (e.g., symptoms of depression).

Despite recent gains in equity, Jewish Americans continue to be a target of prejudice and discrimination. For example, the Federal Bureau of Investigation 2012 Hate Crime Statistics indicate that, during that year, Jews comprised 62.4% of the victims of religion-based hate crimes (Federal Bureau of Investigation, 2013). In a recent study by the Pew Center for Religion and Public Life Project (2013) of more than 3,000 Jewish Americans, 43% agreed with the belief that Jewish Americans are discriminated against in the United States, 12% reported having been called an offensive name in the past year, and 7% reported being snubbed or being left out of social activities. Jewish Americans may feel a sense of discrimination as a group in comparison with the larger White majority, despite their ability to blend in or pass as members of the majority group. Although individual Jewish Americans may not personally have experienced discrimination, they may still feel that they experience discrimination as a group. Similar to other ethnic minorities, for Jewish Americans, ethnic identity may offset the link between discrimination and poor mental health (i.e., depressive symptoms).

College-attending emerging adults

Emerging adults attending college may serve as an ideal sample in which to investigate ethnic identity affiliation. Research indicates that emerging adulthood (approximately ages 18 to 30 years) may represent the time in which individuals are consolidating their identities (Montgomery & Côté, 2003). Although individuals begin exploring and committing to aspects of identity during adolescence, the college experience, where one has to interact with others from diverse cultures, backgrounds, and beliefs, may prompt some introspection and further consolidation of identity (Schwartz, Côté, & Arnett, 2005). For college-attending emerging adults from ethnic minority groups, several studies indicate that ethnic identity consolidation occurs in this time period (e.g., Syed & Azmitia, 2009; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). For Jewish American emerging adults attending college, it is likely that their Jewish American ethnic identities are also consolidated during this time.

The present study

In this study, we investigated ethnic identity among Jewish American, college-attending emerging adults in comparison with other ethnic minorities and with other White Americans. First, we assessed the level of participation in religious practice across groups. Among 301 adults, Kakhnovets and Wolf (2011) had found that global spirituality and religiosity were associated with greater Jewish identity. Given that religious practice may be a central activity in relation to ethnic affiliation for Jewish Americans, we wanted to assess how religiously active the Jewish Americans were in comparison with other ethnic groups, as well as whether participation in religious activities related to ethnic and U.S identity for Jewish Americans.

We proposed three primary hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Jewish Americans would score higher on ethnic identity measures than other White Americans, but, as relatively invisible minorities, their level of ethnic identity would be lower than that of other ethnic minority groups.

Hypothesis 2: Within the Jewish sample, ethnic identity would be associated with self-esteem.

Hypothesis 3: Also within the Jewish sample, ethnic identity would moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health outcomes. The relationship between perceived discrimination and mental health outcomes would be lower for those individuals with strong ethnic identities.

Method

Sample

The present sample is taken from the Multi-University Study of Identity and Culture (MUSIC) dataset (see Weisskirch et al., 2013, for more details). The present analyses included 8,501 individuals (6223 women, 2278 men) from 30 public and private colleges and universities around the United States. None of the sites were Jewish-oriented schools that would unduly attract Jewish students (e.g., Yeshiva University). From the total MUSIC sample, participants ranging in age from 18 to 30 years old were included in these analyses (M = 19.94 years, SD = 1.99 years).

Participants who indicated on a question about religious affiliation that they were Jewish and that they had at least one Jewish parent were labeled as Jews. Participants separately indicated the religious affiliation of their mother and their father. According to traditional Jewish religious law, “being Jewish” is traditionally established matrilineally, regardless of the father’s background. However, among participants identifying as Jewish, preliminary analyses (i.e., analyses of variance) did not indicate differences among individuals with only a Jewish father versus with only a Jewish mother or with both parents being Jewish. In addition, only Jewish Americans who indicated that they were “Caucasian, White, European American, White European, or Other in this category” were included in the sample. Individuals who indicated a Jewish parent but indicated a religious affiliation of anything other than Jewish were removed from the sample. Furthermore, because our study focuses on ethnic identity issues in the United States, we did not want to confound results with immigrant status and therefore also excluded foreign-born participants from any ethnic group. Therefore, the ethnic composition of the final sample includes U.S.-born Jewish Americans (N = 280; 3.3% of the sample), as well as U.S.-born White Americans (64.6%), African Americans (8.6%), Latinos (13.2%), and Asian Americans (10.3%). Other than the Jews, the religious background of the sample comprised 21.9% no religion/atheist/agnostic, 38.8% Protestant, 28.9% Catholic, 3.3% Mormon, 4.9% other, 1.5% Buddhist, and less than 1% each Jehovah’s Witness, Hindu, and Muslim.

Procedures

Participants were recruited from 30 public and private colleges and universities from across the United States. They were drawn from courses in human development and family studies, psychology, social science, business, education, and human nutrition and were directed to an online questionnaire for completion. After granting consent, participants were asked to complete the online questionnaire on their own time. On average, completion took 1–2 hours for all of the measures administered (a subset of which is included in the present analyses). Participants received extra credit or research participation credit for taking part in the study. The institutional review boards at each site approved the study.

Measures

Religious practice

We asked three questions about religious activities and practices. Participants rated the item, “In the last month, how often have you attended a religious service at your church/mosque/synagogue?” using a 5-point scale: 1 = not at all, 2 = less than once per week, 3 = about once a week, 4 = 2–3 times per week, 5 = more than 3 times per week. They also rated the item, “How often do you pray?” using a 5-point scale: 1 = never, 2 = hardly ever, 3 = sometimes, 4 = often, 5 = every day. Participants answered the question, “In terms of religion, how observant are you?” using a 5-point scale: 1 = I do not observe a religion, 2 = I observe during holidays, 3 = I follow some customs regularly, 4 = I follow most of the customs, 5 = I follow all of the customs.

Ethnic identity

To assess ethnic identity, we used Roberts and colleagues’ (1999) MEIM. This measure consists of 12 statements that participants rate using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). An example of an item is “I feel a strong sense of pride in my ethnic group.” It should be noted that the Jews in the sample were not prompted to think of themselves as Jewish for this measure, just as participants from other ethnic groups were not prompted. The measure includes two subscales: ethnic identity search and ethnic group affirmation and belonging. Among a similarly diverse, college-aged sample, Roberts and colleagues (1999) reported reliabilities for the total scale and subscales as .90, .86, and .80, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha for the total score and the search and affirmation/belongingness subscales, respectively, in the current dataset are .91, .79, and .92.

We also used Umaña-Taylor, Yazedijan, and Bámaca-Gómez’s (2004) Ethnic Identity Scale (EIS) to assess ethnic identity affirmation, exploration, and resolution. This measure captures aspects of identity not addressed in the MEIM and provides an additional perspective on ethnic identity. An example resolution item is “I am clear about what my ethnicity means to me.” Again, Jewish Americans in the sample were not prompted to think of themselves as ethnically Jews or Jewish American for this measure. Participants rated the 17 items on this measure using a scale ranging from 1 (does not describe me at all) to 4 (describes me very well). Umaña-Taylor and colleagues (2004) reported alphas of .86, .91, and .92, respectively, for the affirmation, exploration, and resolution subscales among a diverse sample of college students. Cronbach’s alphas in this sample were .85, .89, and .89, respectively.

U.S. identity

We used Schwartz and colleagues’ (2012) adapted version of Phinney’s (1992) MEIM to measure U.S. identity. Participants rated 12 items, such as “I am happy that I am an American,” using a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Schwartz and colleagues (2012) reported Cronbach’s alpha estimates for U.S. identity search and U.S. identity affirmation and belonging subscales as .74 and .93, respectively. In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for the total measure and the two subscales (i.e., U.S. identity search and U.S. identity affirmation and belonging), respectively, were .90, .73, and .93.

Self-esteem

We used Rosenberg’s Self-Esteem Scale (RSES; Rosenberg, 1989) to measure self-esteem. Participants indicated their agreement with each of 10 statements on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A mean self-esteem score is obtained by recoding responses to the negatively worded items and then taking the mean of the item responses. A sample item is “On the whole, I am satisfied with myself.” Previous studies on the RSES in diverse college samples have reported reliabilities ranging from .72 to .88 (Gray-Little, Williams, & Hancock, 1997; Greenberger, Chen, Dmitrieva, & Farruggia, 2003). For this sample, Cronbach’s alpha was .88.

Perceived group discrimination

We used the perceived discrimination scale from the Scale of Ethnic Experience (Malcarne, Chavira, Fernandez, & Liu, 2006) to measure perceived discrimination. On this nine-item measure, participants indicated their agreement with each statement using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item is “Generally speaking, my ethnic group is respected in America” (reverse-scored). Jewish Americans in the sample were not prompted to think of themselves as ethnically Jews or Jewish American for this measure. Previous diverse, college-aged samples generated reliabilities ranging from .76 to .91 for this measure (Malcarne et al., 2006). In the present study, Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was .86.

Mental health outcomes

We used the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) to assess depressive symptoms. Participants rated 20 items on the frequency of occurrence using a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). A sample item is “I felt like crying this week.” Responses are summed to create a total score. Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the present dataset was .86.

Results

Preliminary analyses

To determine whether there were gender differences within the Jewish American sample for the variables of interest, we conducted t tests for each of the variables. Findings indicated only one statistically significant difference. On the EIS affirmation subscale, women (M = 22.72, SD = 2.51) scored significantly higher than men (M = 20.39, SD = 3.92), t(245) = 5.45, p < .001, Cohen’s d = .72. To determine whether there was an association between age and the variables of interest, we computed zero-order correlations and found no significant associations.

Religious participation

To assess whether Jewish Americans in this sample engaged in religious activities more often than members of other ethnic groups, using analysis of variance, we compared their responses on the religious practice items to responses from members of other ethnic groups. In this sample, Jewish Americans were significantly less likely to have attended religious services, prayed, or followed religious customs compared with members of other ethnic groups in the sample. See Table 1 for details.

Table 1.

Religious service attendance, frequency of prayer, and religious observance, by ethnicity.

| Religious service attendance M (SD) | Frequency of prayer M (SD) | Religious observance M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| African Americans | 2.01 (1.05) | 3.80 (1.17) | 3.20 (1.05) |

| Asian Americans | 1.73 (0.99) | 2.71 (1.39) | 2.56 (1.23) |

| White Americans | 1.71 (0.95) | 3.07 (1.39) | 2.82 (1.23) |

| Jewish Americans | 1.51 (0.68) | 2.37 (1.03) | 2.43 (0.74) |

| Hispanic Americans | 1.72 (0.97) | 3.28 (1.26) | 2.81 (1.11) |

| F(4, 8442) = 18.44** | F(4, 8466) = 94.05** | F(4, 8448) = 37.31** |

Note. In pairwise comparisons with Jewish Americans as the referent group, all findings were significant (ps < .01), except for between Jewish Americans and Asian Americans on religious observance.

p < .01.

Ethnic and U.S. identities

Using multivariate analysis of variance, we compared ethnic groups on the MEIM, EIS, and AIM and found that, as hypothesized, there were significant differences among the groups for all variables. To determine the differences between ethnic groups, we conducted planned contrasts with Jewish Americans serving as the reference group. Results indicate that Jewish Americans were significantly different on most of the variables from the other ethnic groups, including White Americans. See Table 2 for details. In particular, supporting our first hypothesis, Jewish Americans were significantly higher on ethnic identity affirmation, ethnic identity search, ethnic identity total, and ethnic identity scale-exploration compared with other White Americans. Jewish Americans were also significantly lower on U.S. identity affirmation compared with other White Americans. Given the absence of differences on U.S. identity exploration or total U.S. identity, the findings only partially support the expectation that Jewish Americans would not differ from other White Americans on U.S. identity. These results, overall, may indicate that Jewish Americans explore and search and experience a sense of affirmation and belonging about their own ethnic backgrounds differently from other White Americans; and that they may feel less of a sense of connectedness to being American than do other Whites.

Table 2.

Multivariate analysis of variance of ethnic identity and American identity scores by ethnic groups.

| Jewish Americans M (SD) | African Americans M (SD) | Asian Americans M (SD) | White Americans M (SD) | Hispanic Americans M (SD) | F(df) | η2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EI affirmation | 27.81 (0.41) | 29.06 (0.27)a | 26.31 (0.23)a | 26.23 (0.09)a | 27.07 (0.21) | 28.31 (4, 6913)** | .02 |

| EI search | 17.21 (0.30) | 17.99 (0.20)a | 16.44 (0.17)a | 15.15 (0.07)a | 15.62 (0.15)a | 60.17 (4, 6913)** | .03 |

| EI total | 45.08 (0.65) | 47.05 (0.44)a | 42.74 (0.37)a | 41.38 (0.15)a | 42.69 (0.33)a | 44.83 (4, 6913) ** | .03 |

| EIS exploration | 18.20 (0.34) | 20.02 (0.23)a | 18.93 (0.20) | 16.26 (0.08)a | 18.54 (0.18) | 109.74 (4, 6913)** | .06 |

| EIS affirmation | 22.21 (0.19) | 21.94 (0.13) | 21.53 (0.11)a | 22.54 (0.04) | 22.34 (0.10) | 20.65 (4, 6913)** | .01 |

| EIS resolution | 10.79 (0.22) | 11.83 (0.15)a | 11.20 (0.12) | 10.54 (0.05) | 11.61 (0.11)a | 34.95 (4, 6913)** | .02 |

| AI affirmation | 28.87 (0.35) | 28.36 (0.24) | 27.13 (0.20)a | 29.82 (0.08)a | 29.10 (0.18) | 44.00 (4, 6913)** | .03 |

| AI search | 18.80 (0.26) | 17.77 (0.17)a | 17.01 (0.13)a | 18.63 (0.06) | 17.63 (0.13)a | 37.14 (4, 6913)** | .02 |

| AI total | 47.66 (0.55) | 46.12 (0.37)a | 44.14 (0.31)a | 48.45 (0.13) | 46.73 (0.28) | 48.66 (4, 6913)** | .03 |

Note. Variables sharing subscripts indicate significant differences in simple pairwise contrasts with Jewish Americans as the referent group. EI = ethnic identity; EIS = ethnic identity scale; AI = American identity.

p < .01.

In addition, because of the lack of engagement in religious activities for the Jewish American group, we examined whether there were differences for those who were more religious versus those who were more secular. For each of the three religious practice items, respectively, we split the sample at the mean to create high- and low-engagement groups and then conducted t tests between the high- and low-engagement groups for the ethnic and U.S. identity subscales. In general, high religious engagement groups provided higher scores on the ethnic identity measures, with the exception of EIS affirmation. High and low frequency of prayer groups differed significantly on U.S. identity search. No other significant differences emerged for U.S. identity. See Table 3 for details.

Table 3.

Comparison of Jewish American low- and high-religious activity for the ethnic identity and American identity variables.

| Religious service attendance |

Frequency of prayer |

Religious observance |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JA-low M (SD) | JA-high M (SD) | t | JA-low M (SD) | JA-high M (SD) | t | JA-high M (SD) | JA-low M (SD) | t | |

| EI affirmation | 27.06 (6.29) | 28.77 (5.62) | t(266) = −2.28* | 26.34 (6.51) | 29.61 (4.88) | t(266) = −4.53** | 26.55 (6.30) | 29.55 (5.27) | t(266) = −4.08** |

| EI search | 16.84 (4.64) | 18.24 (4.26) | t(266) = −2.50* | 16.23 (4.58) | 18.97 (3.99) | t(266) = −5.12** | 16.43 (4.47) | 18.87 (4.25) | t(266) = −4.46** |

| EI total | 43.89 (10.26) | 47.00 (9.19) | t(261) = −2.51* | 42.62 (10.43) | 48.55 (8.14) | t(261) = −4.99** | 42.99 (10.15) | 48.39 (8.72) | t(261) = −4.47** |

| EIS exploration | 17.29 (5.03) | 19.63 (4.73) | t(244) = −3.69** | 17.28 (4.78) | 19.50 (5.10) | t(244) = −3.51** | 17.07 (4.97) | 19.97 (4.62) | t(244) = −4.63** |

| EIS affirmation | 22.09 (3.17) | 22.17 (3.00) | t(245) = −.18 | 22.07 (3.28) | 22.19 (2.87) | t(245) = −0.29 | 22.27 (2.98) | 21.90 (3.27) | t(245) = 0.91 |

| EIS resolution | 10.37 (3.08) | 11.36 (2.66) | t(244) = −2.60** | 10.39 (2.97) | 11.29 (2.85) | t(244) = −2.41* | 10.32 (2.86) | 11.44 (2.97) | t(244) = −2.97** |

| AI affirmation | 28.54 (5.86) | 29.03 (5.11) | t(263) = −.69 | 28.26 (5.45) | 29.39 (5.68) | t(263) = −1.63 | 28.84 (5.39) | 28.89 (5.84) | t(263) = −0.36 |

| AI search | 18.70 (4.10) | 18.89 (3.74) | t(261) = −.38 | 18.22 (4.09) | 19.51 (3.66) | t(261) = −2.66** | 18.51 (4.11) | 19.17 (3.69) | t(261) = 1.33 |

| AI total | 47.22 (9.30) | 47.93 (8.25) | t(262) = −.63 | 46.47 (8.85) | 48.89 (8.77) | t(262) = −2.21* | 47.13 (8.80) | 48.07 (9.00) | t(262) = −0.84 |

p <.05.

p <.01.

Note. EI = ethnic identity; EIS = ethnic identity scale; AI = American identity, JA = Jewish American.

Ethnic identity and self-esteem

We computed bivariate correlations among the variables of interest. See Table 4 for details. To investigate whether ethnic identity was associated with self-esteem for Jewish Americans (Hypothesis 2), we conducted a hierarchical regression using the Jewish American sample. First, we entered the U.S. identity search and affirmation scales in the first block and the ethnic identity measures (i.e., MEIM ethnic identity search and affirmation; EIS affirmation, exploration, and resolution) in the second block with self-esteem as the dependent variable. As noted in Table 5, low ethnic identity search and high ethnic identity affirmation, EIS affirmation, and EIS resolution predicted self-esteem for Jewish Americans. On the basis of these findings, it appears that, as hypothesized (Hypothesis 2), Jewish Americans who have a sense of belonging and resolution as Jewish Americans also report higher self-esteem.

Table 4.

Correlations among the variables for the Jewish American sample

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. EI affirmation | — | .76** | .96** | .51** | .09 | .51** | .52** | .53** | .57** | .24** | .02 | −.03 |

| 2. EI search | — | .92** | .48** | −.11 | .33** | .38** | .60** | .51** | .03 | .19** | .15* | |

| 3. EI total | — | .53** | .03 | .46** | .50** | .60** | .58** | .17** | .09 | .04 | ||

| 4. EIS exploration | — | .08 | .66** | .24** | .29** | .28** | .09 | −.07 | .12 | |||

| 5. EIS affirmation | — | .12 | .16* | .02 | .11 | .40** | −.25** | −.33** | ||||

| 6. EIS resolution | — | .30** | .29** | .32** | .28** | −.13 | −.01 | |||||

| 7. AI affirmation | — | .73** | .95** | .24** | −.03 | −.16** | ||||||

| 8. AI search | — | .90** | .17** | .13 | −.09 | |||||||

| 9. AI total | — | .23** | .04 | −.14* | ||||||||

| 10. Self-esteem | — | −.50** | −.26** | |||||||||

| 11. Depression | — | .21** | ||||||||||

| 12. Perceived discrimination | — |

Note. EI = ethnic identity, EIS = ethnic identity scale, AI = American identity.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 5.

Hierarchical multiple regression of American and ethnic identity measures on self-esteem for only Jewish Americans

| b | SE B | β | R2 or F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | ||||

| AI search | −.22 | .16 | −.01 | |

| AI affirmation | .31 | .11 | .26 | |

| R2 | .07 | |||

| F for change in R | 7.81** | |||

| Model 2 | ||||

| AI search | .24 | .17 | .14 | |

| AI affirmation | .00 | .11 | .00 | |

| EI search | −.39 | .16 | −.26* | |

| EI affirmation | .31 | .12 | .28* | |

| EIS exploration | −.16 | .11 | −.12 | |

| EIS affirmation | .71 | .13 | .32** | |

| EIS resolution | .53 | .18 | .24** | |

| R2 | .27 | |||

| F for change in R | 11.57** |

Note. AI = American identity; EI = ethnic identity; EIS = ethnic identity scale.

p < .05.

p < .01.

We next conducted an analysis of variance to test for differences in perceived discrimination across ethnic groups. There were significant differences by ethnic group, F(4, 7898) = 999.22, p < .001, η2 = .34, with African Americans (M = 3.44, SD = 0.71) having the highest means and, in descending order, Latinos (M = 3.04, SD = 0.79), Asian Americans (M = 2.89, SD = 0.72), Jewish Americans (M = 2.45, SD = 0.74), and White Americans (M = 1.96, SD = 0.76). Pairwise comparisons indicate that means of all groups are statistically significant from one another (ps < .001).

Ethnic identity and depressive symptoms

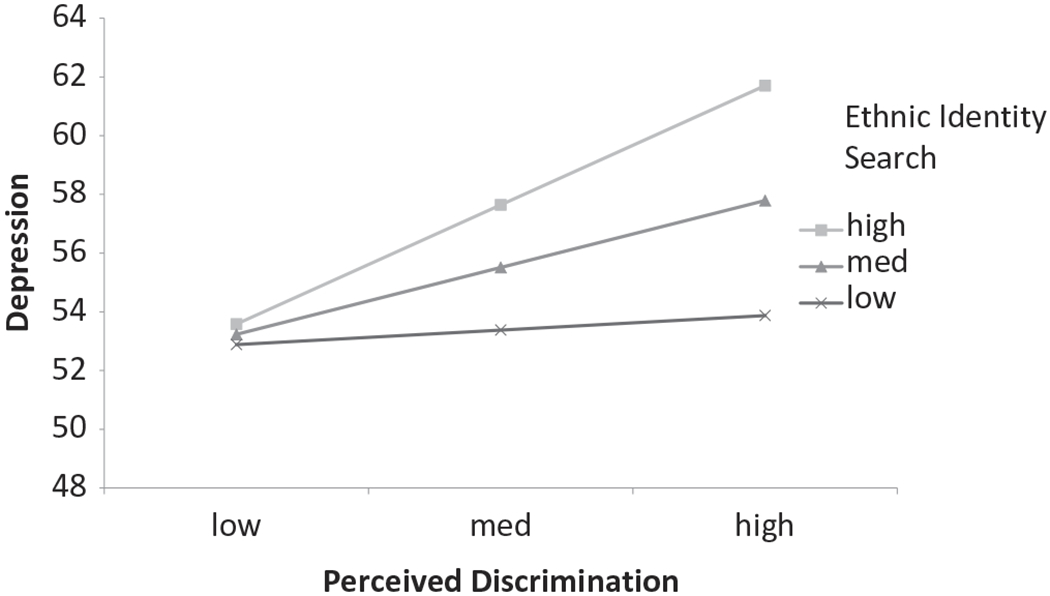

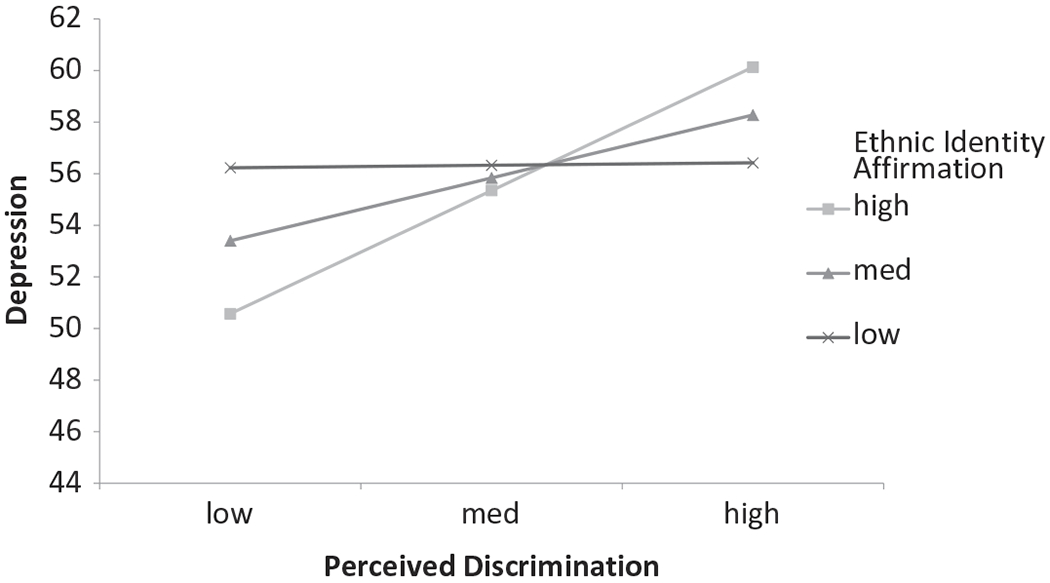

To investigate Hypothesis 3, regarding whether ethnic identity would moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and depression, we first centered the variables by subtracting the mean from each score and then multiplied the centered scores to create an interaction term. We then conducted hierarchical multiple regression analysis to determine moderation with each of the ethnic identity subscales (i.e., ethnic identity search, ethnic identity affirmation, EIS search, EIS affirmation, and EIS resolution) analyzed separately for each predictor. Only two of the possible five moderation effects were significant. Both ethnic identity search and ethnic identity affirmation moderated the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms (see Table 6). That is, those Jewish Americans with greater ethnic identity search and ethnic identity affirmation provided greater depression scores in the face of discrimination (See Figure 1 and Figure 2). The subscales from the EIS measure did not moderate the relationship and are not included here. The findings for the MEIM subscales do provide some support for the hypothesis, but in the opposite direction as anticipated.

Table 6.

Hierarchical multiple regression of moderation of perceived discrimination by ethnic identity scales on depression.

| b | SE B | β | t | R2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | 55.51 | .85 | |||

| PD (centered) | 3.07 | 1.13 | .18 | 2.72** | |

| EI search (centered) | .47 | .19 | .16 | 2.45* | |

| PD × EI search | .53 | .24 | .14 | 2.17* | |

| R2 | .09 | ||||

| Constant | 55.84 | .85 | |||

| PD (centered) | 3.29 | 1.13 | .19 | 2.91** | |

| EI affirmation (centered) | .08 | .14 | .03 | .54 | |

| PD × EI Affirmation | .52 | .21 | .16 | 2.51** | |

| R2 | .07 |

Note. PD = perceived discrimination; EI = ethnic identity.

p < .05.

p < .01.

Figure 1.

Moderation of perceived discrimination, by ethnic identity search on depression.

Figure 2.

Moderation of perceived discrimination, by ethnic identity affirmation on depression.

Discussion

As barriers to education decreased and Jewish Americans became economically upwardly mobile, they have integrated into the larger European-descended, White American group. However, Jewish Americans also have continued to retain unique feelings as a separate ethnic group. The present findings indicate that, at least among the present sample, Jewish American emerging adults do explore and search their ethnic identities more so than do other White Americans, as hypothesized (Hypothesis 1). Findings indicated that Jewish Americans did have higher ethnic identity scores across all of the measures than did other White Americans, but their scores were not as high as ethnic minorities on most of the measures of ethnic identity. However, the findings are mixed in some respects. For example, for the MEIM total score, Jewish Americans scored higher than Hispanic Americans, White Americans, and Asian Americans but lower than African Americans. At the same time, Jewish Americans scored higher on EIS affirmation than Asian Americans did. Perhaps, because of their ability to pass as White, Jewish Americans may not have the same pressures to explore and affirm their ethnic identities as do other ethnic minorities—and indeed, we did not prompt participants to think of themselves as Jewish when completing the study measures. Moreover, although we did not expect that there would be any differences between Jewish Americans and White Americans on American identity, results indicated that Jewish Americans scored significantly lower on American identity affirmation compared with other White Americans (and higher than Asian Americans). These findings, taken together, may indicate that Jewish Americans may retain some feelings of ethnic distinction, despite the appearance of blending into the larger dominant group. Some of this distinction may be due to the casting of the United States as a Christian nation and to lingering anti-Semitism that reminds Jews that they may not be full members of the White American ethnic group.

Despite the mixed findings, there still may be benefits of ethnic identity for Jewish Americans. Among Jewish Americans, ethnic identity may function to bolster self-esteem as is the case for other ethnic minorities. Supporting our second hypothesis, more exploration, having a sense of affirmation about one’s ethnic identity, and having resolved one’s ethnic identity predicted higher self-esteem. This pattern is somewhat consistent with findings with other ethnic groups who experience personal benefits from having explored, feeling a sense of belonging and affirmation from their ethnic group, and having a sense of resolution about their ethnic identities (e.g., Smith & Silva, 2010). This finding may also indicate that there might be a benefit to retaining a sense of one’s own ethnic origins despite being presumed as being part of the larger group. This finding is also consistent with social identity theory, where one’s affiliation with a group may support overall well-being (Tajfel & Turner, 1979). At the same time, high ethnic identity search was also predictive of lower self-esteem, which may indicate that young Jewish Americans who are thinking about their ethnicity may feel less secure and confident about themselves (Greene, Way, & Pahl, 2006). It could be that the process of searching leaves them disconcerted in terms of appreciating their roots as Jewish Americans or in how they fit into the larger ethnic landscape. As immigrant groups have become assimilated into American society, it could be that those who can blend in could still benefit from having a sense of where they come from (Brown, Langille, Tanner, & Asbridge, 2014; Navarro, Ojeda, Schwartz, Piña-Watson, & Luna, 2014).

In the present study, the relationship between perceived discrimination and depressive symptoms was moderated by aspects of ethnic identity, somewhat supporting the third hypothesis. However, the finding was in the opposite direction than we expected. It appears that ethnic identity search and affirmation serve to amplify the link between discrimination and depressive symptoms. This finding is inconsistent with what has been found with visible minority groups, where ethnic identity tends to be protective. It is possible that, for White ethnic groups, engaging with ethnic identity may create feelings of unrest and distress. This finding supports the complexity of Jewish American ethnic identity and may mirror the inconsistency of benefits of ethnic identity for some ethnic groups (Bratt, 2015). However, more research, using longitudinal and experimental designs, is needed to determine precisely how ethnic identity provides support or increases distress (and the ways in which these mechanisms operate). As Persky and Birman (2005) stated, being ethnic is contextually determined and can be based on religion, race, or any other characteristic that differentiates a given group from the dominant group.

Limitations

The findings in this study should be interpreted in light of some important limitations. First, the Jewish Americans in the study were not prompted to think of themselves ethnically as Jewish Americans, and therefore we do not know what they were thinking about when they responded to questions about ethnic identity. However, despite not being prompted to answer questions considering themselves ethnically as Jewish Americans, respondents’ notions of identity may be shaped by past ethnocultural experiences, given the perceived and actual distinctions between Jewish Americans and other White Americans. Second, the indicator for inclusion in the Jewish American sample was response to a question on religious affiliation. As a result, it is possible that individuals in the sample were somewhat religious; ethnically Jewish individuals would have been removed from the sample had they identified themselves as agnostic or atheist. Such exclusions may have biased our results. Third, the colleges and universities from which the sample was drawn may not be representative of Jewish American students’ experiences. That is, some participants may be more aware of being Jewish on some campuses than others because of the demographic mix of the campus. In addition, we did not ascertain the ethnic mix of their hometowns and their experience with past discrimination as Jewish Americans. We also did not ask about their involvement with Jewish campus life. It could be that some of the students are more aware of their identities as a consequence of participating in Jewish-themed activities on campus. Fourth, the engagement in religious activities for this sample was relatively low. It could be that Jewish American college students who engage in more religious activities derive a stronger sense of ethnic identity, and more religious Jewish Americans may seek out religiously oriented colleges and universities. Fifth, given that the Jewish American sample was largely secular, the experiences of Orthodox, Ultra-Orthodox, and Hasidic Jews (among others) were likely not well represented in our results. Sixth, the findings may not be generalizable to other national contexts. Jews may not blend as easily into White majorities in other countries as they may be able to do in the United States.

Conclusion

For Jewish Americans, the inclusion in research as being White may be part of the ascribed identity placed upon them. Jewish Americans, themselves, may not identify themselves according to the common racial and ethnic categories used in research. In some cases, they may develop ethnic identities unique to their experience as a minority group. Yet, Jewish Americans, for the most part, are a diasporic group, having retained their uniqueness because of their historical religious and cultural practices. It is likely that other diasporic groups may develop a sense of ethnic identity as a consequence of distance from others of the same group or place of origin. This pattern of ethnic identity retention may be helpful for other groups who, otherwise, could blend in to the White American mainstream—groups such as Russians, Poles, Armenians, and others. Given the changing demographics in the United States, the promotion of ethnic identity retention in various groups may have long-lasting benefits.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2003). Guidelines on multicultural education, training, research, practice, and organizational change for psychologists. American Psychologist, 58, 377–402. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.58.5.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birman D, Persky I, & Chan WY (2010). Multiple identities of Jewish immigrant adolescents from the former Soviet Union: An exploration of salience and impact of ethnic identity. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 34, 193–205. doi: 10.1177/0165025409350948 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Branscombe NR, Schmitt MT, & Harvey RD (1999). Perceiving pervasive discrimination among African Americans: Implications for group identification and well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77, 135–149. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.77.1.135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bratt C (2015). One of few or one of many: Social identification and psychological well-being among minority youth. British Journal of Social Psychology, 54, 671–694. doi: 10.1111/bjso.12105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodkin K (1998).How Jews became White folks: And what that says about race in America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Langille D, Tanner J, & Asbridge M (2014). Health-compromising behaviors among a multi-ethnic sample of Canadian high school students: Risk-enhancing effects of discrimination and acculturation. Journal of Ethnicity in Substance Abuse, 13, 158–178. doi: 10.1080/15332640.2013.852075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey M, Eaker DG, Fish LS, & Klock K (2003). Ethnic identity in an American White minority group. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 3, 143–158. doi: 10.1207/S1532706XID030204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Devos T, & Mohamed H (2014). Shades of American identity: Implicit relations between ethnic and national identities. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8, 739–754. doi: 10.1111/spc3.12149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubow EF, Pargament KI, Boxer P, & Tarakeshwar N (2000). Initial investigation of Jewish early adolescents’ ethnic identity, stress, and coping. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 20, 418–441. doi: 10.1177/0272431600020004003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Federal Bureau of Investigation. (2013). FBI Uniform Crime Statistics 2013 Hate Crime Statistics. Retrieved from http://www.fbi.gov/about-us/cjis/ucr/hate-crime/2012/topic-pages/victims/victims_final

- Gray-Little B, Williams VSL, & Hancock TD (1997). An item response theory analysis of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 443–451. doi: 10.1177/0146167297235001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberger E, Chen C, Dmitrieva J, & Farruggia SP (2003). Item-wording and the dimensionality of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale: Do they matter? Personality And Individual Differences, 35, 1241–1254. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00331-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene ML, Way N, & Pahl K (2006). Trajectories of perceived adult and peer discrimination among Black, Latino, and Asian American adolescents: Patterns and psychological correlates. Developmental Psychology, 42, 218–236. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollinger DA (2000). Postethnic America. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Iturbide MI, Raffaelli M, & Carlo G (2009). Protective effects of ethnic identity on Mexican American college students’ psychological well-being. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 31, 536–552. doi: 10.1177/0739986309345992 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn NF, & Aronson KM (2012). Jewish American identity: Patterns of centrality and regard. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 12, 185–190. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2012.668729 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kakhnovets R, & Wolf L (2011). An investigation of Jewish ethnic identity and Jewish affiliation for American Jews. North American Journal of Psychology, 13, 501–518. [Google Scholar]

- Koutrelakos J (2013). Ethnic identity: Similarities and differences in White groups based on cultural practices. Psychological Reports, 112, 745–762. doi: 10.2466/17.10.PR0.112.3.745-762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivisto P, & Nefzeger B (1993). Symbolic ethnicity and American Jews: The relationship of ethnic identity to behavior and group affiliation. The Social Science Journal, 30, 1–12. doi: 10.1016/0362-3319(93)90002-D [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malcarne VL, Chavira DA, Fernandez S, & Liu P (2006). The scale of ethnic experience: Development and psychometric properties. Journal of Personality Assessment, 86, 150–161. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa8602_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markstrom CA, Berman RC, & Brusch G (1998). An exploratory examination of identity formation among Jewish adolescents according to context. Journal of Adolescent Research, 13, 202–222. doi: 10.1177/0743554898132006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery M, & Côté JE (2003). College as a transition to adulthood In Adams GR & Berzonsky MD (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of adolescence (pp. 149–172). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Navarro RL, Ojeda L, Schwartz SJ, Piña-Watson B, & Luna LL (2014). Cultural self, personal self: Links with life satisfaction among Mexican American college students. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2, 1–20. doi: 10.1037/lat0000011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Persky I, & Birman D (2005). Ethnic identity in acculturation research: A study of multiple identities of Jewish refugees from the former Soviet Union. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 36, 557–572. doi: 10.1177/0022022105278542 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center’s Religion and Public Life Project. (2013). A portrait of Jewish Americans. Retrieved from http//:www.pewforum.org/files/2013/10/jewish-american-full-report-for-web.pdf

- Phinney JS (1992). The multigroup ethnic identity measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176. doi: 10.1177/074355489272003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponterotto JG, Gretchen D, Utsey SO, Stracuzzi T, & Saya RJ (2003). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM): Psychometric review and further validity testing. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 63, 502–515. doi: 10.1177/0013164403063003010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ponterotto JG, Rao V, Zweig J, Rieger BP, Schaefer K, Michelakou S, … Goldstein H (2001). The relationship of acculturation and gender to attitudes toward counseling in Italian and Greek American college students. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 7, 362–375. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.7.4.362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS (1977). The Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression Scale: A self-report depressionscale for research in the general population. Journal of Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Syed M, Umaña-Taylor A, Markstrom C, French S, Schwartz SJ, & Lee R (2014). Feeling good, happy, and proud: A meta-analysis of positive ethnic–racial affect and adjustment. Child Development, 85, 77–102. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, & Romero A (1999). The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 301–322. doi: 10.1177/0272431699019003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M (1989). Society and the adolescent self-image. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Côté JE, & Arnett J (2005). Identity and agency in emerging adulthood: Two developmental routes in the individualization process. Youth & Society, 37, 201–229. doi: 10.1177/0044118X05275965 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Park IK, Huynh Q, Zamboanga BL, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Lee R, … Agocha V (2012). The American identity measure: Development and validation across ethnic group and immigrant generation. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 12, 93–128. doi: 10.1080/15283488.2012.668730 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Syed M, Yip T, Knight GP, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Rivas-Drake D, & Lee RM (2014). Methodological issues in ethnic and racial identity research with ethnic minority populations: Theoretical precision, measurement issues, and research designs. Child Development, 85, 58–76. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers RM, Rowley SJ, Chavous TM, Shelton JN, & Smith MA (1997). Multidimensional inventory of black identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and constuct validity. Journal of Personality And Social Psychology, 73, 805–815. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.73.4.805 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TB, & Silva L (2010). Ethnic identity and personal well-being of people of color: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58, 42–60. doi: 10.1037/a0021528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein GL, Kiang L, Supple AJ, & Gonzalez LM (2014). Ethnic identity as a protective factor in the lives of Asian American adolescents. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 5, 206–213. doi: 10.1037/a0034811 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, & Azmitia M (2009). Longitudinal trajectories of ethnic identity during the college years. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 19, 601–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00609.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Syed M, & Juang LP (2014). Ethnic identity, identity coherence, and psychological functioning: Testing basic assumptions of the developmental model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20, 176–190. doi: 10.1037/a0035330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajfel H, & Turner J (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict In Austin W & Worchel S (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, … Seaton E (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85, 21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, & Bámaca-Gómez M (2004). Developing the Ethnic Identity Scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 4, 9–38. doi: 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Weisskirch RS, Zamboanga BL, Ravert RD, Whitbourne SK, Park I, Lee RM, & Schwartz SJ (2013). The composition of the Multi-Site University Study of Identity and Culture (MUSIC): A collaborative approach to research and mentorship. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19, 123–130. doi: 10.1037/a0030099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]