Abstract

More than fifty-five thousand children die each year in the United States, very few of whom use hospice at the end of their lives. Nearly one-third of pediatric deaths are a result of chronic, complex conditions, and the majority of these children are enrolled in Medicaid because of disability status or the severity of their disease. Changes in Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program regulations under section 2302 of the Affordable Care Act require all state Medicaid plans to finance curative and hospice services for children. The section enables the option for pediatric patients to continue curative care while enrolled in hospice. We examined state-level implementation of concurrent care for Medicaid beneficiaries and found significant variability in guidelines across the US. The implementation of concurrent care has fostered innovation, yet added barriers to how pediatric concurrent care has been implemented.

More than fifty-five thousand children die each year in the United States. Unfortunately, less than 12 percent of them use hospice at the end of their lives.1,2 Nearly one-third of pediatric deaths are a result of chronic, complex conditions. The majority of these children are enrolled in Medicaid because of disability status or severity of disease.3 Hospice services for children offer an opportunity for family-centered supportive care and symptom management. Hospice care focuses on coordinated services with the goal of minimizing suffering and optimizing the function of the child at the end of life. For children or adolescents, hospice care was previously distinguished from other forms of supportive or palliative care in that it was associated with care delivered in the last six months of life, often provided in the home or a community-based setting.4 Families were forced to make a choice between their child receiving hospice services or curative care.5 The definition of curative care is broad and may include therapies and treatments such as dialysis, chemotherapy, and medications such as those that control neurological symptoms or transplant rejection.6 Advocates of pediatric hospice care recognized that the strict choice between either curative or hospice care was a significant barrier to enrollment in pediatric hospice services at the end of life.7 To overcome this barrier, in the 2000s, several states demonstrated innovation in financing and care models and developed alternative pathways to enrollment in pediatric hospice that allowed children to continue to receive curative care.7

Early state-based initiatives that allowed children to continue to receive curative care while enrolled in hospice offered early proof of concept that informed the inclusion of curative care in the Affordable Care Act (ACA).7 To improve the continuity and quality of end-of-life care, changes in Medicaid/Children’s Health Insurance Program regulations under ACA section 2302 enabled pediatric patients to opt for concurrent care (the continuation of curative care while enrolled in hospice care), which requires all state Medicaid plans to finance both curative and hospice services for children younger than twenty-one.8 ACA section 2302 represents an important regulatory modification to hospice eligibility that went into effect immediately on signing and that requires coordination of multiple stakeholders for successful implementation.

The purpose of our study was to analyze variability in the implementation and scope of coverage of ACA section 2302 across all states. Because ACA section 2302 has been in effect for more than ten years with sparse investigation of how it was implemented at the state level, what we do know is limited.9,10 In 2010, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued a series of three letters to state Medicaid offices notifying them of the change in Medicaid plans.8,11 The letters consisted mainly of the policy paragraph, taken directly from the ACA document, along with preliminary questions and answers. No regulations were generated or distributed to the states. No deadlines for implementation were communicated to the states, nor were penalties issued for late or no compliance. Further, there were no earmarked federal appropriations to support this policy. As a consequence, state-level uptake of ACA section 2302 by state Medicaid plans varied significantly, with some states implementing ACA section 2302 in 2010 and others implementing it as late as 2017.12 Thus far, it has been challenging for policy makers, clinicians, researchers, and state Medicaid administrators to identify best practices, evaluate the effectiveness of various implementation decisions, or assess the overall provision of concurrent care.

Study Data And Methods

Using data collected from publicly available Medicaid documents, we conducted a pooled, cross-sectional comparative analysis of all state guidelines for the implementation of pediatric concurrent hospice care. From 2010 to 2017, state Medicaid offices issued publicly available information about pediatric concurrent care implementation.6 Information for this project was collected over the course of four months, from May 2019 to August 2019. State-specific Medicaid Hospice Provider Manuals, state plan amendments, and memos were the main source of information for this project, especially with regard to the areas of definitions of curative care, payment, care coordination between hospice and curative providers, staffing, eligibility, and clinical guidance. The analysis included all states and Washington, D.C.

Data Extraction And Coverage Score Calculation

We developed a systematic search and data extraction template to abstract key elements from the Medicaid pediatric concurrent care documents. Elements that were included in the data extraction process included definition, payment information, staffing guidelines, care coordination requirements, eligibility criteria, and clinical guidance. These elements were chosen on the basis of clinical, policy, and administrative relevance.

After we extracted the data, we calculated an overall guideline implementation score for each state based on a summation of individual elements. In addition to making it possible to compare individual states, the overall score allowed for a comparison of states’ performance. Guideline scores of the concurrent care elements were aggregated at the state level, and state performance was calculated by summing the elements present for the state. States were ranked from highest to lowest on their implementation of guideline elements.

Limitations

This study is limited by reliance on publicly available documents regarding pediatric concurrent care at the state level. It is possible that some states offered guidance or plans for implementation of ACA section 2302 but did not make those documents publicly available. However, making recommendations widely available is one way that states can ensure consistent implementation: If guidance is available but not widely accessible, states may be hampered in implementing the policy effectively. In addition, some states are continuing to develop or refine policies around concurrent care. This study offers a snapshot of policies a decade into the concurrent care provision and may help provide a road map to guide further development of implementation plans.

Study Results

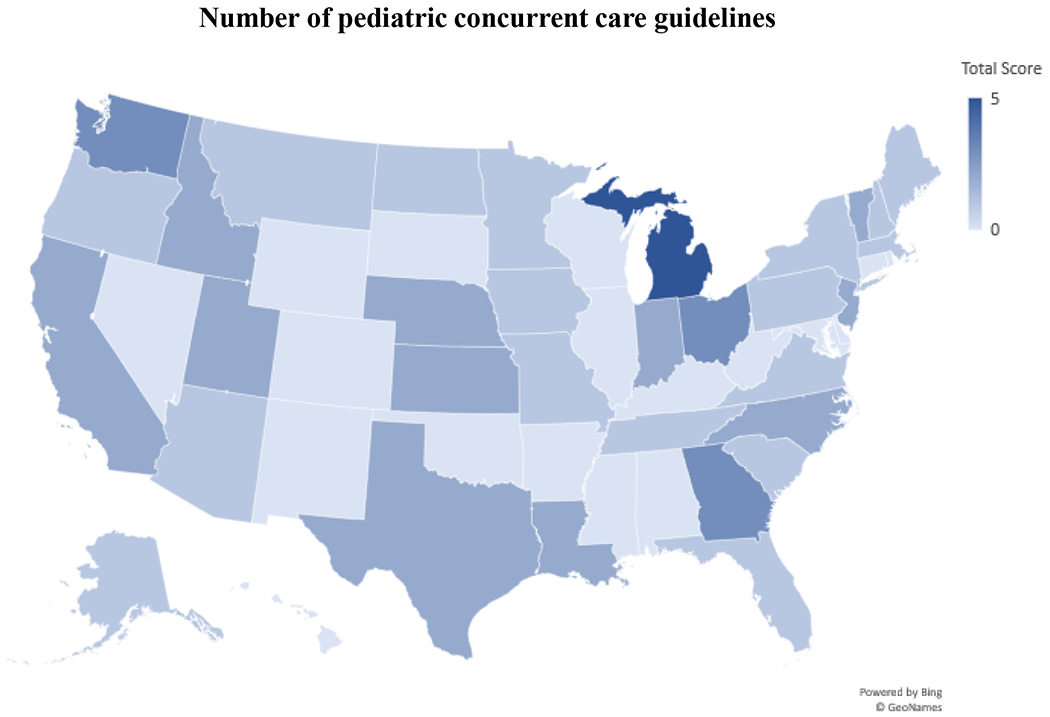

The analysis included fifty states and Washington, D.C. Exhibit 1 displays the total number of state-specific pediatric concurrent care guidelines by state. Michigan had the highest number of guidelines in five categories, including guidelines for definitions, payment, staffing guidelines, care coordination, and clinical guidance. Nineteen states (that is, Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, South Dakota, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, and Washington, D.C.) offered no state-specific guidelines on concurrent care.

The most common guidelines implemented were definitions (35.29 percent), followed by payment information (29.41 percent), care coordination requirements (27.45 percent), staffing guidelines (5.88 percent), eligibility criteria (3.92 percent), and clinical guidance (2.00 percent). Eighteen states (that is, California, Vermont, Florida, Maine, Michigan, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Georgia, Nebraska, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Tennessee, Texas, New Hampshire, Oregon, and Washington) provided definitions of services related to the treatment of the terminal illness. Terms such as curative, life-prolonging, and disease-directed care were used interchangeably. In addition, state-level definitions referred to therapies, treatments, and/or medications. Some states such as California simply defined these services as curative treatments.13 Delaware, Florida, Michigan, and Ohio described services for terminal illness as a blended package of curative and palliative services, which were medically necessary to correct or ameliorate a defect, condition, or physical or mental illness. Specific examples of hospice and terminal illness services were listed in the Michigan guidelines.14 However, there was no standard definition for the services related to terminal illness under concurrent care among the states.

Guidelines for the payment of concurrent care varied widely. Fifteen states (that is, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Jersey, California, Idaho, Georgia, Kansas, Ohio, Utah, Washington, and Texas) implemented procedures for provider reimbursement. For example, Iowa state Medicaid paid for curative treatments and hospice care separately after private insurance reimbursement.15 In Michigan, hospice services and curative treatment were billed and reimbursed separately14: Before filing for reimbursement, Michigan providers had to differentiate between which services were palliative and were included in hospice reimbursement and which services were curative and separately reimbursed under Michigan Medicaid. In Texas, the Medicaid guidelines shifted concurrent care reimbursement from managed care to fee-for-service (for example, carve-out services).16 Each state offered unique guidelines for provider payment under concurrent care.

Care coordination guidelines were present in fourteen states (that is, Washington, Georgia, Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Montana, North Carolina, Ohio, South Carolina, Vermont, Virginia, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Michigan). Most states discussed the importance of care coordination by the hospice team. Rarely did states discuss how hospice and nonhospice providers coordinate care, which is especially important in the context of concurrent care. Idaho placed the responsibility of care coordination on the hospice provider.17 In Idaho, the hospice provider was responsible for all services related to the terminal illness regardless of whether they are supplied directly by the hospice provider or by a nonhospice provider. In addition, it was the hospice’s responsibility to communicate and coordinate all services included in the patient’s plan of care, including billing processes. Specific care coordination plans were required in Indiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Ohio. Michigan required care coordination between the hospice and nonhospice (for example, subspecialists) to be detailed in the child’s plan of care.14 Care coordination guidelines were inconsistent among all states.

Only three states included guidelines on staffing concurrent care. Alaska and Michigan outlined roles and responsibilities for hospice and nonhospice clinical staff, including private duty nursing and pediatric subspecialists.14,18 Under Utah Medicaid guidelines, pediatric hospice providers were responsible for developing a training curriculum for both paid and unpaid hospice staff members who provided care to clients younger than twenty-one.19 The goal of the Utah pediatric-specific training was to offer specialized knowledge about pediatric care that meets children’s unique developmental, social, and emotional needs. Core components of the Utah training curriculum include information on pediatric growth and development; pediatric pain and symptom management; loss, grief, and bereavement care for pediatric families and the child; and pediatric psychosocial and spiritual care.

It was uncommon for states to include guidelines on unique eligibility and clinical practice, although all states noted the pediatric concurrent care eligibility guidelines directly from the statute (ACA, section 2302). North Dakota extended the age range of concurrent care from younger than twenty-one to younger than twenty-three.20 Arizona offered flexibility on the six-months-to-live prognosis as a hospice eligibility criteria.21 Michigan was the only state to include medical record review guidance and postpayment audit information.14

Discussion

The Concurrent Care for Children provision of the Affordable Care Act (section 2302) offers an important opportunity to children with life-limiting illness and their families, who are no longer forced to choose between hospice and curative care. The purpose of concurrent care is to help children at the end of their life have the best quality of life for as long as possible.

Yet this critically important opportunity has come with limited guidance for implementation, resulting in significant variability in how concurrent care has been carried out across the US. Nineteen states plus Washington, D.C., have decided to rely only on the direct language that was in the ACA for implementation of concurrent care. Additional research might explore whether these states used undocumented approaches (for example, the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization’s Concurrent Care Toolkit)11 or documented their implementation guidelines in non–publicly available resources.

Thirty-two states developed their own pediatric concurrent care implementation guidelines. These guidelines demonstrate extreme variability across the important dimensions of implementation such as definition, payment information, staffing guidelines, care coordination requirements, eligibility criteria, or clinical guidance. For example, Utah’s policy leads the way in training staff in the provision of such care.

Nationally, pediatric hospice care is frequently provided by staff with limited pediatric experience and training.22 Given the unique needs of terminally ill children, the provision of concurrent care in pediatrics is complex. Without appropriate training, hospice providers may fail to meet the unique developmental needs of children, as well as the psychosocial challenges of death within a young family. In addition, hospice providers without experience with concurrent care may fail to grasp its importance or provide care in concordance with child and family goals.23 Hospice nurses consistently report that they want training in pediatric care24; the addition of staffing guidelines might offer an opportunity to ensure that hospice workers receive the training they want and need. Future research is needed to evaluate the impact of guidelines such as staffing on workforce, care delivery, and ultimately, patient outcomes.

The findings from our study have policy implications. First, preserving these types of guideline innovations at the state level is critical. Our findings highlighted the differences between states that did and did not have guidelines. Among the states that did implement concurrent care guidelines, there were innovative approaches to implementation, which might serve as examples for others. Innovations that demonstrate effectiveness in improving concurrent care can then be scaled and spread more broadly for use by others. Scaling and dissemination of effective interventions is a key factor in closing the gap between a best-known practice and common practice.25 Allowing for innovation was a lesser-known but important section of the ACA (section 1332). In 2014, states had the opportunity to apply for a state innovation waiver that allowed them to pursue their own strategy to ensure that their residents had access to high-quality, affordable insurance.26 However, in pursuing these waivers, states had to show that their proposals met four criteria ensuring protections of state residents and the federal budget.27 A similar road map holds the potential to improve concurrent care implementation through adoption of a guideline that preserves enough flexibility to improve the quality of concurrent care by evaluating and spreading promising innovations.

Second, the framework we created to extract information could serve states as a basic guide to identify gaps in concurrent care guidelines: common definition, payment information, staffing guidelines, care coordination requirements, eligibility criteria, or clinical guidance. National end-of-life groups or coalitions could convene appropriate state-level stakeholders from Medicaid offices, hospices, children’s hospitals, hospice associations, and pediatric coalitions to initiate conversations about improvements and modifications to guidelines. Stakeholders need to ensure their guidelines are consistent with current Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Conditions of Participation and other federal regulations (for example, the ACE Kids Act of 2019). Guideline development should also consider the impact on providers who lack pediatric knowledge, especially because more than three-fourths of adult hospice-only providers care for children.28 A guideline that is easy to understand will enable adult hospice providers to more smoothly transition to providing concurrent care for terminally ill children.

Conclusion

In summary, concurrent care allows children with life-limiting illness to receive both curative care and hospice care. This strategy meets the goals of many patients and families to live as well as possible for as long as possible. Prior demonstration work has identified lower costs and higher quality of life for children under community-based palliative care,19 and concurrent care may have similar effects. Our findings highlighted the significant variation in concurrent care guidelines among the states and suggests actionable items for future research. This study has policy implications for key stakeholders as they seek to address the gaps in their pediatric concurrent care guidelines.

Figure 1.

Number of pediatric concurrent care guidelines implemented in the US, by state, 2019

Acknowledgment

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01NR017848 (to Lisa Lindley). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Special thanks to Jamie Butler and Theresa Profant for their assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Special thanks to Ms. Jamie Butler and Ms. Theresa Profant for their assistance in preparing the manuscript.

Funding: This publication was made possible by Grant Number R01NR017848 from the National Institute of Nursing Research (Lindley). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research or National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Jessica Laird, College of Nursing, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996.

Melanie J. Cozad, Department of Health Services Policy and Management, Center for Effectiveness Research in Orthopedics, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29201.

Jessica Keim-Malpass, School of Nursing, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 22908.

Jennifer W. Mack, Department of Pediatric Oncology and Division of Population Sciences, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02214.

Lisa C. Lindley, College of Nursing, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Knoxville, Tennessee 37996.

Notes

- 1.Murphy SL, Mathews TJ, Martin JA, Minkovitz CS, Strobino DM. Annual summary of vital statistics: 2013–2014. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindley LC, Mixer SJ, Mack JW. Home care for children with multiple complex chronic conditions at the end of life: The choice of hospice versus home health. Home Health Care Serv Q. 2016;35(3-4):101–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindley LC, Lyon ME. A profile of children with complex chronic conditions at end of life among Medicaid beneficiaries: implications for health care reform. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(11):1388–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindley LC, Keim-Malpass J. Access to pediatric hospice and palliative care In: Ferrell BR, Paice JA, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. Fifth edition New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindley LC. Healthcare reform and concurrent curative care for terminally ill children: a policy analysis. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2011;13(2):81–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Laird JM, Lindley LC. Pediatric concurrent hospice care: how did states implement? Knoxville (TN): University of Tennessee, Knoxville, College of Nursing; 2019. October (Policy Brief No. 19-001). https://pedeolcare.utk.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Policy-Brief-concurrent-implementation.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keim-Malpass J, Hart TG, Miller JR. Coverage of palliative and hospice care for pediatric patients with a life-limiting illness: a policy brief. J Pediatr Health Care. 2013;27(6):511–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Center for Medicaid, CHIP and Survey and Certification. HHS letter to state Medicaid directors on hospice care for children in Medicaid and CHIP [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services; 2010. September 9 [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/doc/37423817/HHS-Letter-to-State-Medicaid-Directors-on-Hospice-Care-for-Children-in-Medicaid-and-CHIP [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindley LC, Edwards S, Bruce DJ. Factors influencing the implementation of health care reform: an examination of the Concurrent Care for Children provision. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(5):527–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindley LC, Keim-Malpass J, Svynarenko R, Cozad MJ, Mack JW, Hinds PS. Pediatric concurrent hospice care: a scoping review and directions for future nursing research. J Hosp Palliat Nurs. 2020;22(3):238–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. Concurrent Care for Children implementation toolkit [Internet]. Alexandria (VA): NHPCO; 2013. [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.nhpco.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/CCCR_Toolkit.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keim-Malpass J, Lindley LC. Repeal of the Affordable Care Act will negatively impact children at end of life. Pediatrics. 2017;140(3):e20171134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.California Department of Health Care Services. Letter to county California Children’s Service Program administrators on concurrent care [Internet]. Sacramento (CA): DHCS; 2011. October 7 [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/ccs/Documents/ccsnl061011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 14.Michigan Department of Community Health. Concurrent hospice and curative care for children [Internet]; 2011. March 1 [cited 2020 Aug 11]. (Bulletin No. MSA 11-11). Available from: https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/MSA_11-11_346829_7.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.State of Iowa, Department of Human Services. Curative care for hospice children Affordable Care Act section 2302 [Internet]. Des Moines (IA): Department of Human Services; 2011. January 19 [cited 2020 Aug 11]. (Informational Letter No. 981). Available from: https://dhs.iowa.gov/sites/default/files/981_CurativeCareforHospiceChildren.pdf?071620201404 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Texas Department of Aging and Disability Services. Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program hospice care services—concurrent treatment services for individuals under 21 years of age [Internet]. (Provider Information Letter No. 10-107). Austin (TX): Department of Aging and Disability Services; 2010. August 2 [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://apps.hhs.texas.gov/providers/communications/2010/letters/IL2010-107.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 17.Idaho Department of Health and Welfare. Idaho State Plan Amendment 13-009 regarding hospice care for children [Internet]. Boise (ID): Idaho Department of Health and Welfare; 2013. August 26 [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://healthandwelfare.idaho.gov/Portals/41/Images/Documents/SPA13-009.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Alaska State Plan Amendment (SPA) transmittal number 13-007 [Internet]. Baltimore (MD): CMS; 2013. August 13 [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.medicaid.gov/sites/default/files/State-resource-center/Medicaid-State-Plan-Amendments/Downloads/AK/AK-13-007-Ltr.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Utah Department of Health-Medicaid. Section 2: hospice care provider manual. [Internet]. Salt Lake City (NV): Utah Department of Health-Medicaid; 2013. [last updated 2019 Jan; cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://medicaid.utah.gov/Documents/manuals/pdfs/Medicaid%20Provider%20Manuals/Hospice/Hospice.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 20.North Dakota Department of Human Services. Children’s hospice services [Internet]. Bismarck (ND): North Dakota Department of Human Services; 2013. [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.nd.gov/dhs/info/pubs/docs/medicaid/brochure-children-hospice-waiver.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System. AHCCCS Medical Policy Manual [Internet]. Phoenix (AZ): AHCCCS; 2010. [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.azahcccs.gov/shared/MedicalPolicyManual/ [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaye EC, Gattas M, Kiefer A, Reynolds J, Zalud K, Li C, et al. Provision of palliative and hospice care to children in the community: a population study of hospice nurses. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2019;57(2):241–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gans D, Kominski G, Roby D, Diamant A, Chen X, Lin W, et al. Better outcomes, lower costs: palliative care program reduces stress, costs of care for children with life-threatening conditions [Internet]. Los Angeles (CA): UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2012. August [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/Documents/PDF/ppcpolicybriefaug2012.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye EC, Applegarth J, Gattas M, Kiefer A, Reynolds J, Zalud K, et al. Hospice nurses request paediatric-specific educational resources and training programs to improve care for children and families in the community: qualitative data analysis from a population-level survey. Palliat Med. 2020;34(3):403–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Spreading changes [Internet]. Boston (MA): Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2020. [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: http://www.ihi.org/Topics/Spread/Pages/default.aspx [Google Scholar]

- 26.White House, Office of the Press Secretary. Press release, fact sheet: the Affordable Care Act: supporting innovation, empowering states; 2011. February 28 [Internet]. Washington (DC): White House; 2011 [cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2011/02/28/fact-sheet-affordable-care-act-supporting-innovation-empowering-states [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lueck S, Schubel J. Understanding the Affordable Care Act’s state innovation (“1332”) waivers [Internet]. Washington (DC): Center on Budget and Policy Priorities; [last updated 2017 Sep 5; cited 2020 Aug 11]. Available from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/health/understanding-the-affordable-care-acts-state-innovation-1332-waivers [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lindley LC, Edwards SL. Geographic variation in California pediatric hospice care for children and adolescents: 2007–2010. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2018;35(1):15–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]