Abstract

Cold-water corals (CWCs) are important habitats for creatures in the deep-sea environment, but they have been degraded by anthropogenic activity. So far, no genome for any CWC has been reported. Here, we report a draft genome of Trachythela sp., which represents the first genome of CWCs to date. In total, 56 and 65 Gb of raw reads were generated from Illumina and Nanopore sequencing platforms, respectively. The final assembled genome was 578.26 Mb, which consisted of 396 contigs with a contig N50 of 3.56 Mb, and the genome captured 90.1% of the metazoan Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs. We identified 335 Mb (57.88% of the genome) of repetitive elements, which is a higher proportion compared with others in the Cnidarians, along with 35,305 protein-coding genes. We also detected 483 expanded and 51 contracted gene families, and many of them were associated with longevity, ion transposase, heme-binding nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, and metabolic regulators of transcription. Overall, we believe this genome will serve as an important resource for studies on community protection for CWCs.

Keywords: cold-water coral, deep sea, genome, nanopore

Significance

Cold-water coral communities are important habitats for creatures in the deep sea. Previous studies have shown that the increase in human activity presents a huge threat to these vulnerable ecosystems. Herein, we present the first draft genome of a cold-water coral (Trachythela sp.). The key contribution of this present work is that the results will benefit the protection of this important ecosystem.

Introduction

Cold-water corals (CWCs) live in the cold, dark, and hypoxic deep-sea waters and are widespread around the world (Roberts et al. 2006). Most CWCs must attach to hard-bottom substrates to grow, and only a few can live on soft sediments (Roberts et al. 2006; Hebbeln et al. 2020). Due to the lack of symbiotic zooxanthellae, they do not require sunlight as a source of energy (Malakoff 2003; Roberts et al. 2006; Roberts and Cairns 2014), and their major source of nutrients is the microscopic zooplankton that comes from passing currents or descends from the surface of the ocean. Most CWC species have long life spans and slow growth rates. Thus, they are excellent materials for palaeoclimatic and paleoceanographic reconstructions (Frank et al. 2011; Thierens et al. 2013; Struve et al. 2020).

The complexity of CWC structures provide important benthic habitat and nurseries for larvae of many deep-sea species (Roberts and Hirshfield 2004; Roberts, et al. 2006; Auster et al. 2011; Baillon et al. 2012). However, CWCs are increasingly facing existential threats (Roberts et al. 2006) (e.g., destruction by trawl fishing) (Rogers 1999). Additionally, ocean acidification has already impacted coral reef ecosystems; CWCs are highly sensitive to ocean acidification because the saturation of CaCO3 in the deep sea is lower than shallow-water environments (Li et al. 1969; Maier et al. 2012). Accidental oil spills have also inflicted an unprecedented impact on deep-sea ecosystems, which include CWCs (White et al. 2012; Girard et al. 2018). Moreover, other anthropogenic activities (e.g., mineral extraction, oil and gas exploration) have noticeably affected the health of CWC ecosystems as well (Roberts et al. 2006; Foley et al. 2010). More recently, the impact of macroplastics and microplastics on CWCs has been put under the spotlight worldwide (Chapron et al. 2018; Mouchi et al. 2019). Under the many different threats, the ecological stability of CWC ecosystems are being affected by the rapid changes in oceans globally, and these ecosystems will take hundreds or thousands of years to return to their previous level of health (Rogers 1999).

Increasing human activity and global environmental change will threaten CWC ecosystems further. In addition, the genetic architecture of CWCs is still poorly understood (Pratlong et al. 2015; Glazier et al. 2020). Here, we present a draft genome of Trachythela sp., which is a CWC, by using a combination of Illumina and Nanopore sequencing technologies. We believe that this first draft genome of a CWC is an important resource for forthcoming research on these species and will facilitate studies on the protection of this vulnerable ecosystem.

Materials and Methods

Sample Process, Library Construction, and Sequencing

A colony specimen of Trachythela sp. was collected from a slope of the Xisha Trough (18°53′N, 112°66′E, July 2019) in the South China Sea (SCS) by the manned submersible Shenhaiyongshi at a depth of ∼1,068 m (supplementary fig. S1, Supplementary Material online). The sample was cut into small pieces and preserved in liquid nitrogen immediately. The species was identified by sequencing the mitochondrial genome (GenBank accession number MW238423) and comparing it with the mitochondrial gene database (unpublished) of Catherine S. McFadden (Harvey Mudd College, USA). Genomic DNA was extracted by using a Qiagen Genomic DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany). DNA quality and quantity were checked using 1% agarose gel electrophoresis and a Qubit2.0Flurometer (Life Technologies, CA), respectively. Only high-quality DNA (OD260/280:1.8–2.0 and OD 260/230: 2.0–2.2) was used for library preparation and whole-genome sequencing. A total of 1.5 µg DNA was fragmented to construct a library of 350 bp by using a Truseq Nano DNA HT Sample Preparation Kit (Illumina). Also, 150-bp paired-end reads were sequenced by an Illumina NovaSeq platform (Illumina). In addition, 20-kb Nanopore libraries were constructed and sequenced on a Nanopore PromethION (Oxford Nanopore Technologies, UK).

Genome Assembly

The raw data were filtered based on the method described by Liu et al. (2020). In brief, Illumina raw data were filtered by Fastp (v0.19.6, Chen et al. 2018), and genome size of Trachythela sp. was estimated using Jellyfish software (v1.1.10, Marcais and Kingsford 2011). Nanopore raw data were filtered by ontbc (https://github.com/FlyPythons/ontbc, last accessed February 15, 2019) with the following parameters: –min_score 7 –min_length 1000, and then the data were assembled by NextDenovo (v2.2, https://github.com/Nextomics/NextDenovo, last accessed December 27, 2020) with “seed_cutoff” set at 4,896. Then, the raw assembly was polished with Illumina short reads using Nextpolish (v1.1.0, Hu et al. 2020), which was conducted twice. Finally, the duplicated genes in the assembly were removed by using Purge_Haplotigs software (v1.1.1, Roach et al. 2018). The completeness of the final genome assembly was assessed by Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (v4.1.4, Seppey et al. 2019) using the “metazoa_odb10” database.

Genome Annotation

For the repetitive sequences, we first used RepeatModeler (v2.0, Tarailo-Graovac and Chen 2009) for de novo construction of a local library, then the homolog repeats were annotated using RepeatMasker (v3.3.0, Tarailo-Graovac and Chen 2009). The transposable elements (TEs) were also annotated by RepeatMasker and RepeatProteinMask (v3.3.0) against the Repbase-20181026 with the parameters -noLowSimple -pvalue 1e-04 (Tarailo-Graovac and Chen 2009). The tandem repeats were further identified using Tandem Repeats Finder software (v4.07b) with these parameters: Match = 2, Mismatch = 7, Delta = 7, PM = 80, PI = 10, Minscore = 50. (Benson 1999).

We used Augustus (v3.2.1, Stanke et al. 2008) to perform de novo gene prediction. For homology-based prediction, protein sequences of Acropora digitifera (GCA_000222465.2), Dendronephthya gigantea (GCF_004324835.1), Stylophora pistillata (GCF_002571385.1), and Nematostella vectensis (GCA_000209225.1) were downloaded from the NCBI database, Porites lutea was downloaded from http://reefgenomics.org/, and then these protein sequences were aligned to the repeats of a soft-masked genome by TBlastN (v2.2.29, Altschul et al. 1990) with a cut-off -evalue 1e-5. In addition, the results from de novo and homology prediction were integrated using EVidenceModeler (v1.1.1, Haas et al. 2008).

Gene functional annotation for Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways was conducted using InterProScan (v5.39-77.0, Jones et al. 2014).

Phylogenetics and Molecular Dating

To define the phylogenetic position of Trachythela sp., we used proteome data from 17 Cnidaria genomes, which included nine stony coral, three soft corals, three sea anemones, and one species of hydra (supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online). The comparison of these protein set was implemented in OrthoFinder (v2.3.1, Emms and Kelly 2015) with the alignment program Diamond (v0.9.25, Buchfink et al. 2015). The single-copy orthologues were subjected to multiple sequence alignment by MUSCLE (v3.8.1551, Edgar 2004) with default parameters. Then, the low-quality alignments were trimmed by TrimAl (v1.2, Capella-Gutierrez et al. 2009), and the phylogenetic tree was built by RAxML (-m GTRGAMMA -f a -x 12345 -N 100 -p 12345-T 30) (v8.2.12, Stamatakis 2014) using the maximum likelihood method (bootstrap repeat was 100). The MCMCtree program was implemented in PAML (v4.9, Yang 2007) to calculate divergence time. The date of the three nodes that were constrained with fossil records (Hydra–Anthozoa: 512–741 Ma, Corallimorpharia–Hexacorallia: 263–445 Ma, Pennatulacea–Octocorallia: 218–419 Ma) was based on the Timetree website (http://www.timetree.org/).

Analysis of Gene Families

Based on the results of OrthoFinder, expansions and contractions of gene families of Trachythela sp. were evaluated in CAFÉ (v4.0, De Bie et al. 2006) with default parameters. In addition, gene families that experienced significant expansion and contraction (P-values <0.05) were also used for KEGG and GO enrichment analysis (Chi.FDR < 0.05).

TE Activity and Demographic History

TE activity and demographic history were analyzed using the same method, which was described by Wang et al. (2019). To rebuild the TE accumulation, we used the publicly available parseRM.pl Perl script (version 5.8.2, downloaded from https://github.com/4ureliek/Parsing-RepeatMasker-Outputs, last accessed October 18, 2017) to parse the age category of each TE copy based on the alignment files from RepeatMasker (v3.3.0, Kapusta et al. 2017). The mutation rate was set at 0.0084 site per million years, which was re-estimated by r8s (v1.81, Sanderson 2003) using the penalized likelihood method. The result was packed into bins per 0.1 Ma. We further applied the Pairwise Sequentially Markovian Coalescence model (Li and Durbin 2011) that was based on heterozygous sites to infer the demographic history of Trachythela sp. The cleaned Illumina reads were mapped to the final genome assembly using BWA-mem (Li and Durbin 2010). Heterozygous sites were extracted by performing Samtools (v1.3.1, Li et al. 2009) with the parameters “mpileup -q 20 -Q 20.” Finally, the PSMC model (Li and Durbin 2011) was analyzed using the parameters -N25 -t15 -r5 -b -p “4þ25*2þ4þ6.” (ZHu et al. 2020).

Results and Discussion

Genome Sequencing and Assembly

After filtering the low-quality data, we generated a total of 56 Gb (∼96.8-fold coverage of the genome) of Illumina raw reads and 65 Gb (∼110.7-fold coverage of the genome) of Nanopore raw reads. The 23-mer survey showed that the genome of Trachythela sp. was 1.87% heterozygous (supplementary fig. S2, Supplementary Material online) and indicated that the size of the genome was ∼585 Mb. Comparison with the heterozygosity levels of other corals (e.g., Acropora millepora: 2.0%, Montipora capitata: 1.3%; Helmkampf et al. 2019; Ying et al. 2019) showed that the coral genomes are generally highly heterozygous. After polishing and curating the heterozygous genome, the final draft genome of Trachythela sp. was 578.3 Mb. The final contig N50 and N90 values were 3.56 and 0.67 Mb, respectively (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). We assessed the completeness of this draft genome by Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs, and the result indicated that 90.7% (865) of the 954 metazoan BUSCOs was complete (supplementary table S3, Supplementary Material online). All these results revealed that this genome was one of the more complete genomes assembled for Cnidarians.

Gene Prediction and Functional Annotation

Overall, we identified 334.7 Mb (57.88%) repetitive sequences in the assembled genome (supplementary tables S4 and S5, Supplementary Material online). This proportion was higher than the values of other available cnidarian genomes. Combined with the results of de novo gene prediction and homology annotation, a total of 35,305 protein-coding genes were predicted. Overall, 32,426 of all genes were annotated by InterProScan, which represented 91.85% of the total genes (supplementary table S6, Supplementary Material online).

Phylogenetics and Analysis of Divergence Time

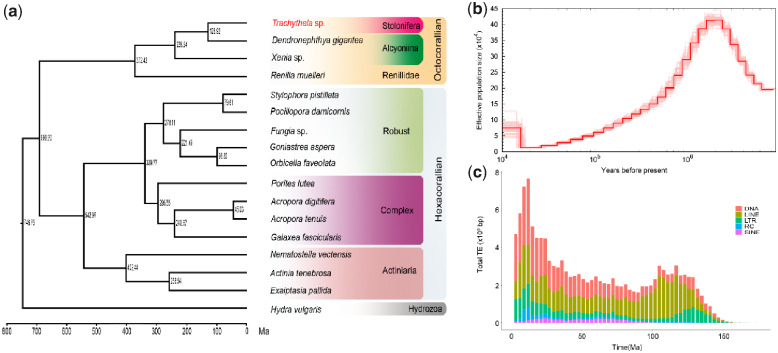

The phylogenetic tree was constructed based on 395 single-copy orthologues. All nodes with the maximum bootstrap support were 100. Estimation of divergence time with fossil-calibration suggested that Trachythela sp. and D. gigantea diverged ∼128.92 Ma (fig. 1a). After its first description in 1922 (Verrill 1922), the genus Trachythela still lacked sufficient morphological and genetic data. In this study, the phylogenetic analysis showed that Trachythela sp. was close to the family Alcyoniina, which will help the taxonomic revision of this family.

Fig. 1.

Evolutionary analysis of Trachythela sp. (a) Phylogeny and divergence time (Ma) of 17 Cnidaria species. (b) Demographic profiles of Trachythela sp. from the PSMC estimation. (c) The whole landscape of TEs accumulation along the timeline.

Expansions and Contractions of Gene Families

We detected 483 expanded and 51 contracted gene families by comparative genomic analyses among 17 Cnidaria species. KEGG enrichment analysis showed that significantly expanded gene families were mainly involved in the categories of RNA degradation, nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism, the longevity regulating pathway, and mismatch repair (FDR < 0.05, supplementary table S7, Supplementary Material online). GO enrichment analysis showed that most of the expanded gene families were related to DNA repair, telomere maintenance, calcium ion binding, ion transposase activity, and heme-binding terms (C.FDR < 0.05, supplementary table S8, Supplementary Material online). The contracted gene families were enriched in the GO categories of scavenger receptor activity, calcium ion binding, and serine-type endopeptidase activity (supplementary table S9, Supplementary Material online).

TE Activity and Population History

Analysis of demographic history indicated that the effective population size of Trachythela sp. reached a peak at ∼1.1 Ma, and then it experienced a decline (fig. 1b). Furthermore, analysis of TE accumulation suggested that Trachythela sp. had undergone two concentrated TE expansions at 110 and 10 Ma (fig. 1c).

In conclusion, we obtained the first genome sequence of the CWC Trachythela sp. The high ratios of repetitive sequences and the significant expansion and contraction of gene families indicated that the adaptive mechanisms of CWCs were for darkness, cold, and high pressures in the deep sea.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data are available at Genome Biology and Evolution online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors want to thank the crew of the vessel Tansuo 1 and the pilots of the HOV Shenhaiyongshi. We appreciate Prof. Catherine S. McFadden (Harvey Mudd College, USA) for her helpful advice in specimen identification. We also would like to thank Thomas A. Gavin, Professor Emeritus, Cornell University, for valuable suggestions regarding the manuscript. This study was supported by the Major Scientific and Technological Projects of Hainan Province (ZDKJ2019011), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC0304905, 2018YFC0309804), and Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA22040502).

Author Contributions

Y.Z. and H.-B.Z. designed the study. J.L. and S.-Y.C. collected the samples. Y.-J.P. prepared DNA for sequencing. Y.Z. and C.-G.F. performed the genomics analysis. Y.Z. and H.-B.Z. drafted the manuscript. Y.Z., J.L., C.-G.F., and H.-B.Z. revised the manuscript. All authors approved the final submission.

Data Availability

All raw sequencing data for this article have been deposited at GenBank under accession number PRJNA661975 (BioSamples SAMN16072316, SRA of Nanopore reads: SRR12668977, SRA of Illumina data: SRR12667698). The genome and mitogenome were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers JADLSH000000000 and MW238423, respectively.

Literature Cited

- Altschul S, Gish W, Miller W, Myers E, Lipman D. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 215(3):403–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auster PJ, et al. 2011. Definition and detection of vulnerable marine ecosystems on the high seas: problems with the “move-on” rule. ICES J Mar Sci. 68(2):254–264. [Google Scholar]

- Baillon S, Hamel J-F, Wareham VE, Mercier A. 2012. Deep cold‐water corals as nurseries for fish larvae. Front Ecol Environ. 10(7):351–356. [Google Scholar]

- Benson G. 1999. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 27(2):573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. 2015. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 12(1):59–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capella-Gutierrez S, Silla-MartinezJM, Gabaldon T. 2009. trimAl: a tool for automated alignment trimming in large-scale phylogenetic analyses. Bioinformatics 25(15):1972–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapron L, et al. 2018. Macro-and microplastics affect cold-water corals growth, feeding and behaviour. Sci Rep. 8(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S, Zhou Y, Chen Y, Gu J. 2018. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34(17):i884–i890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Bie T, Cristianini N, Demuth JP, Hahn MW. 2006. CAFE: a computational tool for the study of gene family evolution. Bioinformatics 22(10):1269–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 32(5):1792–1797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emms DM, Kelly S. 2015. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 16(1):157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley NS, van Rensburg TM, Armstrong CW. 2010. The ecological and economic value of cold-water coral ecosystems. Ocean Coast Manage. 53(7):313–326. [Google Scholar]

- Frank N, et al. 2011. Northeastern Atlantic cold-water coral reefs and climate. Geology 39(8):743–746. [Google Scholar]

- Girard F, Shea K, Fisher CR. 2018. Projecting the recovery of a long‐lived deep‐sea coral species after the Deepwater Horizon oil spill using state‐structured models. J Appl Ecol. 55(4):1812–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Glazier A, et al. 2020. Regulation of ion transport and energy metabolism enables certain coral genotypes to maintain calcification under experimental ocean acidification. Mol Ecol. 29(9):1657–1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haas BJ, et al. 2008. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biol. 9(1):R7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebbeln D, et al. 2020. Cold-water coral reefs thriving under hypoxia. Coral Reefs 39(4):853–857. [Google Scholar]

- Helmkampf M, Bellinger MR, Geib S, Sim SB, Takabayashi M. 2019. Draft genome of the rice coral Montipora capitata obtained from linked-read sequencing. Genome Biol Evol. 11(7):2045–2054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Fan J, Sun Z, Liu S. 2020. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long read assembly. Bioinformatics 36(7):2253–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones P, et al. 2014. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30(9):1236–1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapusta A, Suh A, Feschotte C. 2017. Dynamics of genome size evolution in birds and mammals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 114(8):E1460–E1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. 2010. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 26(5):589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R. 2011. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature 475(7357):493–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, et al. 2009. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 25(16):2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y-H, Broecker W, Takahashi T. 1969. Degree of saturation of CaCO3 in the oceans. J Geophys Res. 74(23):5507–5525. [Google Scholar]

- Liu R, et al. 2020. De novo genome assembly of limpet Bathyacmaea lactea (Gastropoda: Pectinodontidae): the first reference genome of a deep-sea gastropod endemic to cold seeps. Genome Biol Evol. 12(6):905–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maier C, Watremez P, Taviani M, Weinbauer M, Gattuso J. 2012. Calcification rates and the effect of ocean acidification on Mediterranean cold-water corals. Proc R Soc B. 279(1734):1716–1723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malakoff D. 2003. Cool corals become hot topic. Science 299(5604):195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcais G, Kingsford C. 2011. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics 27(6):764–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouchi V, et al. 2019. Long-term aquaria study suggests species-specific responses of two cold-water corals to macro-and microplastics exposure. Environ Pollut. 253:322–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratlong M, et al. 2015. The red coral (Corallium rubrum) transcriptome: a new resource for population genetics and local adaptation studies. Mol Ecol Resour. 15(5):1205–1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roach MJ, Schmidt SA, Borneman AR. 2018. Purge Haplotigs: allelic contig reassignment for third-gen diploid genome assemblies. BMC Bioinformatics 19(1):460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JM, Cairns SD. 2014. Cold-water corals in a changing ocean. Curr Opin Environ Sustain. 7:118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts JM, Wheeler AJ, Freiwald A. 2006. Reefs of the deep: the biology and geology of cold-water coral ecosystems. Science 312(5773):543–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts S, Hirshfield M. 2004. Deep‐sea corals: out of sight, but no longer out of mind. Front Ecol Environ. 2(3):123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers AD. 1999. The biology of Lophelia pertusa (Linnaeus 1758) and other deep‐water reef‐forming corals and impacts from human activities. Int Rev Hydrobiol. 84(4):315–406. [Google Scholar]

- Sanderson MJ. 2003. r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics 19(2):301–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seppey M, Manni M, Zdobnov EM. 2019. 2019. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness. Methods Mol Biol. 1962:227–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. 2014. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics 30(9):1312–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanke M, Diekhans M, Baertsch R, Haussler D. 2008. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24(5):637–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struve T, Wilson DJ, van de Flierdt T, Pratt N, Crocket KC. 2020. Middle holocene expansion of pacific deep water into the Southern Ocean. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 117(2):889–894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarailo-Graovac M, Chen N. 2009. Using RepeatMasker to identify repetitive elements in genomic sequences. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 25(1):4.10.11–14.10.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierens M, et al. 2013. Cold-water coral carbonate mounds as unique palaeo-archives: the Plio-Pleistocene Challenger Mound record (NE Atlantic). Q Sci Rev. 73:14–30. [Google Scholar]

- Verrill AE. 1922. Report of the Canadian arctic expedition 1913–1918. Vol. VIII, Part G. Alcyonaria and Actinaria. Ottawa (ON: ): F.A. Acland; p. 1–87. [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, et al. 2019. Nanopore sequencing and de novo assembly of a black-shelled Pacific oyster (Crassostrea gigas) genome. Front Genet. 10:1211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HK, et al. 2012. Impact of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on a deep-water coral community in the Gulf of Mexico. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 109(50):20303–20308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. 2007. PAML 4: phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Mol Biol Evol. 24(8):1586–1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying H, et al. 2019. The whole-genome sequence of the coral Acropora millepora. Genome Biol Evol. 11(5):1374–1379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu C, et al. 2020. Draft Genome Assembly for the Tibetan Black Bear (Ursus thibetanus thibetanus). Front Genet. 11:231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All raw sequencing data for this article have been deposited at GenBank under accession number PRJNA661975 (BioSamples SAMN16072316, SRA of Nanopore reads: SRR12668977, SRA of Illumina data: SRR12667698). The genome and mitogenome were deposited in the GenBank database under accession numbers JADLSH000000000 and MW238423, respectively.