Abstract

In recent years, the necessity of providing online interventions for adolescents, as an alternative to face-to-face interventions, has become apparent due to several barriers some adolescents face in accessing treatment. This need has become more critical with the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic impacting the delivery of psychotherapy and limiting accessibility of face-to-face therapy. Whilst it has been established that face-to-face psychotherapy for adolescents with personality disorder can be effective in reducing the impact these complex mental illnesses have on functioning, online interventions for adolescents are rare, and to our knowledge there are no empirically validated online interventions for personality disorder. The development of novel online interventions are therefore necessary. To inform the development of online interventions for adolescents with personality disorder or symptoms of emerging personality disorder, a two-phase rapid review was conducted. Phase one consisted of a search and examination of existing online mental health programs for adolescents with symptoms of personality disorder, to understand how to best use online platforms. Phase two consisted of a rapid review of empirical literature examining online interventions for adolescents experiencing symptoms of personality disorder to identify characteristics that promote efficacy. There were no online programs specific to personality disorder in adolescence. However, 32 online mental health programs and 41 published empirical studies were included for analysis. Common intervention characteristics included timeframes of one to two months, regular confidential therapist contact, simple interactive online components and modules, and the inclusion of homework or workbook activities to practice new skills. There is an urgent need for online interventions targeting personality dysfunction in adolescence. Several characteristics of effective online interventions for adolescents were identified. These characteristics can help inform the development and implementation of novel online treatments to prevent and reduce the burden and impact of personality disorder, or symptoms of emerging personality disorder, in adolescents. This has implications for the COVID-19 pandemic when access to effective online interventions has become more urgent.

Key words: Adolescents, personality disorder, online intervention, COVID-19

Introduction

Personality disorders are complex mental illnesses and, as such, have a pervasive impact on functioning particularly if they are not treated early (Chanen et al., 2009; Grenyer, Ng, Townsend, & Rao, 2017). Studies have recently shown that of all mental health presentations to hospital, 20.5% of emergency department and 26.6% of inpatients had a primary diagnosis of personality disorder (Lewis, Fanaian, Kotze, & Grenyer 2019). Data supports a prevalence of personality disorders in the community at 6.5% (Jackson & Burgess, 2000). Further, an estimated 40-50% of psychiatric patients have a personality disorder with 22% of psychiatric outpatients having the diagnosis of Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD; Korzekwa, Dell, Links, Thabane, & Webb, 2008). Presentation in emergency wards is common for those with personality disorder, particularly BPD, which often involves selfharm and suicidality.

Psychotherapy is the first line of treatment for personality disorders, with no recognised pharmacological interventions (National Health and Medical Research Centre [NHMRC], 2012). Intervention using targeted, evidencebased psychotherapy may prevent symptom escalation and reduce cost of hospitalisations. Empirically-based psychotherapy has been shown to significantly reduce direct and indirect health care costs and burden of disease, particularly when intervention occurs early in the symptom trajectory (Chanen et al., 2009). One study found a mean cost saving for treating BPD with evidence-based therapy of USD $2,987.82 per patient per year (Meuldijk, McCarthy, Bourke, & Grenyer, 2017).

As personality disorders tend to emerge in adolescence, early intervention efforts seek to target this developmental stage to prevent symptoms, such as suicidality, self-harm and emotional dysregulation, from worsening (Grenyer et al., 2017). While there is ongoing debate regarding the diagnosis of personality disorder, in particular BPD, during adolescence (Miller, Muehlenkamp, & Jacobson, 2008), current evidence suggests personality disorders can be diagnosed during these years and individuals respond to prevention and intervention for personality disorder (Chanen & McCutcheon, 2013; Johnson et al., 2000; Kaess, Brunner, & Chanen, 2014). Further, access to treatment early in the symptom trajectory also has potential to decrease incidents of deliberate selfharm and suicidal behaviour that may otherwise impact emergency services (Grenyer et al., 2017). As such, adolescence is a key period to target (Chanen et al., 2009), but interventions developed specifically with adolescents in mind are rare (Chanen et al., 2009).

Evidence supports efficacy of face-to-face psychotherapy for personality disorder (Levy, McMain, Bateman, & Clouthier, 2018), however results are subject to publication bias with therapy not being effective for all individuals (Cristea et al., 2017). Therefore, there is a need to address how therapy can be accessible and helpful for more individuals with personality disorder. For some individuals, location and resources limits accessibility and given the increasing use of digital technology in young people’s lives, online therapy could be used to overcome these barriers (Clark, Kuosmanen, & Barry, 2015) The international coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to an even more urgent need to deliver online psychotherapy as it has placed strain on the ability to provide face-to-face therapy to individuals with personality disorder (Álvaro et al., 2020). People with existing mental health conditions are particularly vulnerable to anxiety, feelings of uncertainty and social isolation that COVID-19 mitigation measures have entailed (Sher, 2020; Yao, Chen, & Xu, 2020), motivating a push for greater access to telehealth and internet therapy (Zhou et al., 2020). High treatment seeking and severity of illness means that improving access particularly within this period is crucial. Problems may be further exacerbated for young people with mental health issues, with social isolation, loss of structured work/school environments and changes to service delivery thought to increase risk (Power, Hughes, Cotter, & Cannon, 2020).

Regardless of COVID-19 related restrictions, access problems often preclude young people from beginning their treatment journey, particularly if they reside in rural or remote locations where face-to-face therapy is not available (Grenyer et al., 2017). Therapist-assisted online therapy has been proposed as a means of bridging access gaps and providing treatment when face-to-face contact is not feasible (Johansson et al., 2012). Internet delivery means therapy can be accessed regardless of restrictions, including those imposed by COVID-19 mitigation measures. Online therapy is also not restricted by geographic location or office hours and is less time-consuming, making it more cost effective, and allowing therapists to treat more clients (Hedman et al., 2011; Vigerland et al., 2016). Furthermore, it has been proposed that this type of therapy is well suited to adolescents, due to their willingness to engage with online platforms (Pretorius et al., 2009). Research on internet-delivered psychotherapy for other mental health conditions (e.g., depression, anxiety, bulimia nervosa, suicidal ideation) has demonstrated that adolescents find online therapies acceptable and appealing, and appreciate the confidentiality they afford (Christensen, Batterham, & O’Dea, 2014; Pretorius et al., 2009; Richardson, Stallard, & Velleman, 2010). Further, adolescents may be more competent and confident using online platforms than older adults (Richardson et al., 2010) and online therapy may address concerns around stigma associated with seeking help (Vigerland et al., 2016).

Internet-delivered therapies often take a guided-selfhelp approach, with clients gradually completing activities and modules and the therapist providing continuous support (e.g., Johansson et al., 2012). In addition, this approach commonly includes therapist contact, usually via webcam or secure online messaging system (e.g., Johansson et al., 2012). A review on the acceptability of online mental health programs for adolescents and young people found that completion rates were higher when there was concurrent therapist contact alongside the online component and young people reported therapist assistance allowed an opportunity to share experiences and receive support, and made the programs feel more personable (Struthers et al., 2015). However, high quality studies evaluating the effectiveness of online interventions, including the addition of therapist involvement, is limited and warrants further investigation (Ye et al., 2014).

Previous research has demonstrated the equivalence of online therapies to face-to-face treatments of anxiety and depression for both adults and adolescents (e.g., Andrews, Cuijpers, Craske, McEvoy, & Titov, 2010; Hedman et al., 2011; Richardson et al., 2010; Vigerland et al., 2016). Internet-based therapies have also shown promise for reducing self-harm (Lewis, Heath, Michal, & Duggan, 2012) and suicidal ideation (Christensen et al., 2014), two symptoms closely associated with personality disorder, or emerging personality disorder. What remains unknown is whether these online interventions can be applied to adolescent personality dysfunction. As such, this study aims to identify characteristics that maximise effectiveness of online psychotherapy for adolescents with personality disorder or showing signs and symptoms of emerging personality disorder. We aim to identify relevant existing online interventions and empirical literature on online interventions prior to the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic, to inform development of novel interventions. More specifically, the review will be presented in two parts: an examination of the characteristics of existing online mental health programs that target personality disorder or symptoms of emerging personality disorder for adolescents (a scoping review); and a review of empirical literature evaluating online interventions that target personality disorder or symptoms of emerging personality disorder for adolescents (rapid review). Taken together, it is hoped that results and recommendations from these reviews may inform development of feasible, acceptable and effective online interventions for personality disorder and emerging personality disorder in adolescents, with implications for the COVID-19 global pandemic.

Materials and Methods

This research will use scoping review and rapid review methodology conducted prior to the declaration of the COVID-19 pandemic to answer the question: What characteristics are common to online intervention approaches for adolescents with personality disorder, or adolescents showing signs and symptoms of emerging personality disorder? This will involve identification and examination of existing online mental health programs that target personality disorder or emerging personality disorder symptoms for adolescents, and a rapid review of the empirical literature to inform how these may be adapted to inform online interventions.

Phase one: Scoping review

During January and February 2020, a search of existing publicly available online apps and websites dealing with adolescent interventions with an interactive online component was conducted. A grey literature scoping review search was conducted using the search engines Google and Google scholar. In addition, well-known mental health organisations were searched, and online interventions known to the researchers were also included.

Scoping review methodology was selected to identify what online interventions targeting personality disorder or symptoms of emerging personality disorder were currently available, and the features and content used to address adolescent mental health (Munn et al., 2018). Grey literature searches can identify content that is accessible to the public (Adams et al., 2016; Benzies, Premji, Hayden, & Serrett, 2006; Godin, Stapleton, Kirkpatrick, Hanning, & Leatherdale, 2015). Google and Google Scholar were chosen as they yield large results and speed up the required searching time (Haddaway, Collins, Coughlin, & Kirk, 2015).

Selection process

Due to time and resource demands, search engines were limited to the top 100 results. An initial search indicated the minimal number of any interventions targeted towards personality disorder in adolescents. The following search terms were therefore chosen to broaden the scope of the searches in order to yield a larger variety of interventions. This included programs which targeted symptoms that are commonly recognised in adolescents with personality disorder or emerging personality disorder (i.e. depression, suicide, and self-harm; Chanen, Jovev, & Jackson, 2007; Kaess et al., 2013) and which were recognised to already have a large evidence-base for online therapy (i.e. depression and anxiety; Calear & Christensen, 2010; Clarke et al., 2015; Struthers et al., 2015) to help identify what would be effective for online programs targeting personality disorder or emerging personality disorder. The search terms used were: online therapy, or e-therapy, or app, or self-help or online intervention, or online treatment; and adolescent, or teen, or child; and personality disorder, or depression or suicide or self-harm or self-injury or cutting or mental health or borderline. Despite the aim of the research targeting adolescents specifically, child was included as a search term due to differences in definition and age-range of adolescents. We used the world health organisation (WHO) age range of 10 to 19 years old (World Health Organisation [WHO], 2020a). Inclusion criteria included online apps or websites dealing with adolescents or young people (from age 10 to age 25) mental health interventions with an interactive component. Programs targeting young adults, classified as ages 20 to 25 were included in analysis due to many of programs targeting both adolescents and young adults and the acknowledgment that effective components may overlap.

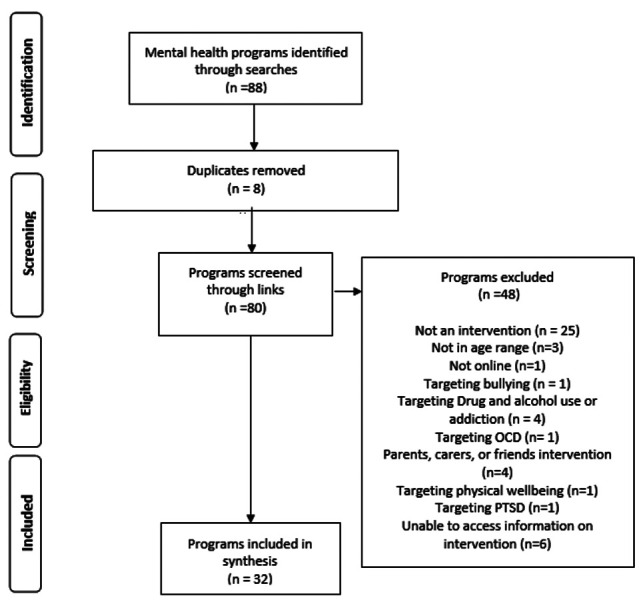

We aimed to identify mental health programs that addressed self-harm, suicidality, interpersonal difficulties, emotion regulation difficulties, and other features of personality disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; World Health Organization, 2018). However, the results were not limited to this due to the lack of interventions that target this, and no programs specific to personality disorder were identified. We therefore included depression, generalised anxiety and general mental health programs in our analysis due to the symptom overlap and comorbidity with personality disorder symptoms (i.e. BPD in adolescents comorbidity and symptomology: Chanen et al., 2007; Ha, Balderas, Zanarini, Oldham, & Sharp, 2014). Exclusion criteria included programs targeted towards individuals out of the 10 to 25 year age range, programs not designed to target mental health, programs designed to target mental health aspects not applicable to emerging personality disorder, [including chronic pain, chronic health conditions, eating disorders, parents and carer interventions, alcohol and drug use and addiction, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)], programs with no online app or website component, programs with no interactive component, online helpline or therapist communication platform only, websites and apps that were not interventions, and programs where the authors could not access any information without a reference or payment required. In addition to this, mental health organisations were searched, any references to other interventions during the search were identified, and any known interventions not already identified were also included. The study flow is presented in Figure 1.

Data extraction

Screening was conducted by one author (EM) and a discussion took place between authors to review screening and decide the final programs to include for review. Once screening was completed, the authors discussed elements to review. Data was extracted by one author (EM) and these included structure of the programs, interactive elements of the program and information about how the content of the program was presented to participants. A second author (SR) then reviewed the data extraction. Once initial review was complete, authors discussed data and considered most essential information.

Phase two: Rapid review of empirical literature

Phase two involved a rapid review of the literature to explore characteristics that may enhance efficacy of online mental health interventions targeting personality disorder or emerging personality disorder symptoms for adolescents, conducted in January 2020. We were interested in data around efficacy of online interventions and characteristics those interventions share. Rapid reviews streamline traditional systematic review methods to achieve a synthesis of evidence within a short timeframe (Haby et al., 2016), and have been shown to generate similar conclusions to those from more intensive systematic reviews when undertaken in a structured and transparent manner (Abou-Setta et al., 2016; Varker et al. 2015).

Selection process

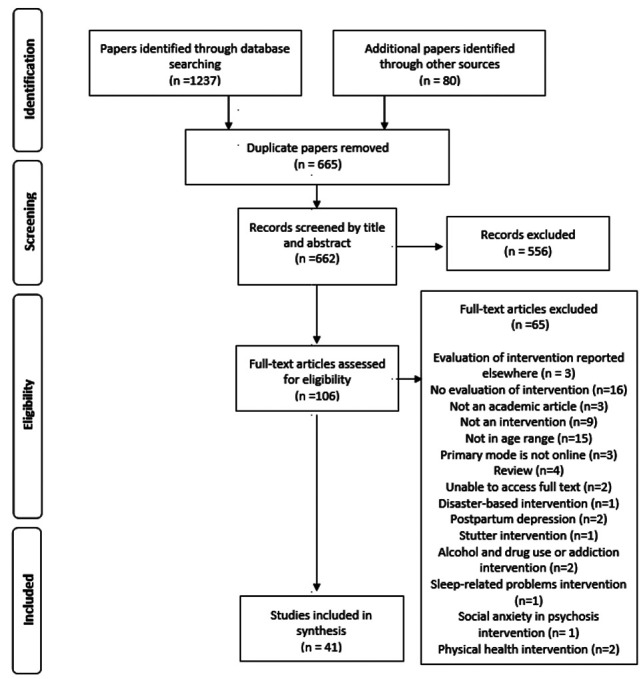

We aimed to keep our methodological decisions as close as possible to those used in the scoping review. As in the scoping review, search terms were chosen to yield a broad variety of interventions due to the lack of specific interventions which target personality disorder. This included programs which targeted symptoms that are commonly recognised in adolescents with personality disorder or emerging personality disorder (i.e., depression, suicide, and self-harm; Chanen et al., 2007; Kaess et al., 2013) and which were recognised to already have a large evidencebase for online therapy (i.e., depression and anxiety; Calear & Christensen, 2010; Clarke et al., 2015; Struthers et al., 2015). Three databases were searched (PSYCInfo, Scopus, and ProQuest central) using a combination of the search terms: online therapy, or online treatment, or online intervention, or online self-help, or e-therapy, or internet therapy or internet-based CBT, or internet-based cognitive behaviour therapy, or internet-based therapy, or internetbased psychotherapy, or internet-based treatment, or internet- based intervention; and adolescent, or teen, or young people, or young person, or youth; and personality disorder, or depression, or suicide, or self-harm, or self-injury, or cutting, or mental health, or borderline; and efficac*, or effectiv*, or outcome*, or impact*, or improv*. In addition, any efficacy papers identified during phase one based on the apps and website interventions were included in screening. Any additional research papers known to the researchers were also included in screening. After an initial search of PSYCInfo database, authors discussed inclusion and exclusion criteria. As with the scoping review, inclusion criteria included any empirical studies that evaluated the effectiveness of adolescents (age 10 to 19) and young people (age 20-25) online mental health interventions. We were particularly interested in interventions targeted towards emotion regulation, interpersonal difficulties, selfharm, suicidality, and other emerging personality disorder symptoms. However, due to the lack of interventions developed specifically for personality disorder, interventions targeting depression, generalised anxiety, and general mental health and wellbeing were included because of the recognised symptom overlap and comorbidity with personality disorder (i.e., BPD in adolescents comorbidity and symptomology: Chanen et al., 2007; Ha et al., 2014). Exclusion criteria included interventions that were not psychological, interventions that did not target mental health, interventions that targeted non-relevant, and specific mental health concerns (including mental health impact of chronic or other health conditions, neurobiological disorders, sleep-related disorders, grief and loss, children of parents with mental illness, brain tumours and injuries, eating disorders, alcohol and drug use and addiction, pregnancy and postnatal depression, PTSD, OCD, Tourette’s, domestic violence, and chronic pain), review articles, articles with no evaluation of the intervention (for example, protocol papers), interventions targeted for individuals outside a 10-25 age range, and interventions where the primary mode of delivery was not online. The study flow is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram for phase one: scoping review.

Data extraction

Screening of all articles and data extraction was conducted by one author (EM). All screening and data extraction were then reviewed by a second author (SR) and any discrepancies were discussed.

Results

Phase 1: Scoping review

Results from phase one are presented in Table 1. Of the 32 programs reviewed, eight (5%) specifically targeted adolescents, three (9%) targeted both adolescents and adults, three (9%) targeted both children and adolescents, three (9%) were directed towards older adolescents or young people (18-25 years old) or tertiary students, eight (25%) were targeted to adults, including young people aged 18 to 25 years, and seven (22%) had no age target. The primary mode of delivery for 17 (53%) of the programs was online, 11 (34%) of the programs were delivered via a phone application (App), and four (13%) had both online and app delivery.

Structure and practical components of the programs

The structure of the programs varied depending on whether they were delivered online or via app and whether they were modelled on evidence-based therapy models (for example, cognitive behaviour therapy). Apps were generally less structured, and 14 (44%) of the programs did not include specific sessions or modules. Eighteen programs (56%) had specific sessions or modules, the terms used to describe the sessions included modules, lessons, challenges, units, or activities. On average, programs had 7.2 sessions (SD=2.2, range= 4-14) with some programs tailoring content and sessions based on personal responses to initial assessment or personal goals.

Programs were recommended to be completed either daily, weekly, or fortnightly, ranging in the time required per session from 10-15 minutes to four hours. Majority of programs required sessions to be completed in a sequential order, or recommended order of sessions, however some were less structured with self-paced completion of sessions, within either long time frames (for example, 90 days) or no time frames. Two (6%) of the programs were specifically designed as a game and involved completing levels or challenges.

Five (16%) of the programs included therapist contact, either via email, online platform, or telephone. Of the 27 (84%) programs that did not provide access to a therapist, eight had the option to share or link data to a personal health professional, and three were specifically designed for this purpose, with one program only being available after a referral by a health professional. Four (13%) of the programs also provided resources or sessions for parents or carers, with one of these programs being specifically designed for the parent or carer to mentor the young person through the program.

Program elements

All programs included information and content related to the mental health difficulties being addressed. How this information was communicated varied and included text, video files, audio files, images, and comics. Some of the programs also included case studies or real-life examples both in text and video format to communicate information. All programs also provided some information on skills or tips to overcome or manage the mental health difficulties discussed. Some programs provided interactive activities or games to practice skills, such as simple breathing or focus exercises, and others provided homework and downloadable/printable content to practice skills away from the program.

Other common features of the programs included an initial assessment in the form of a telephone call or online questionnaire, with feedback; surveys or quizzes to monitor symptoms or check knowledge; opportunities to make personal goals and review progress made towards goals; feelings, mood, or anxiety trackers often in the form of ratings out of ten when logging-on to the program; sections for journal or diary entries to track thoughts and experiences; additional resources and relaxation exercises; forums or chat rooms to connect with peers; and email reminders, online calendars or encouragements to help keep participants on track.

Phase 2: Rapid review

Results of the rapid review of empirical literature are presented in Table 2. No studies directly targeting personality disorder in adolescence were identified. Those reviewed represent interventions targeting conditions and symptoms related to personality disorder in young people or emerging personality disorder. Of the 41 studies reviewed, the most common target problem was depression 44%, 18 studies); followed by anxiety (20%, 8 studies), depression and anxiety together (17%, 7 studies), and suicidal behaviours/ideation (10%, 4 studies). Other studies targeted non-suicidal self-injury (2%, 1 study), mental wellbeing generally (2%, 1 study), and one intervention was multi-diagnostic and tested with adolescents in inpatient care (2%). One study (2%; Alvarez-Jimenez et al., 2018) evaluated an intervention targeting young people at high risk of developing psychosis. After a full-text screening of this study, it was reviewed due to the high similarities in symptomology for young people considered at high risk for psychosis and those with personality disorder symptoms.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram for phase 2: Rapid review of empirical literature.

Approximately half of the studies (51%, 21 studies) reported results of randomised control trials, with pilot studies (17%, 7 studies) and feasibility and/or acceptability trials also common (10%, 4 studies). It should be noted that summary statistics reported reflect the number of articles identified, rather than number of interventions. As such the same intervention may be examined more than once within Table 2.

Whilst all studies included adolescent participants (aged 10-19 years), some studies also included either young adults (20-25 years; 34%, 14 studies) or children (0-9 years; 2%, 1 study) in their sample. One additional study examined psychiatric nurse data for the purposes of evaluating the adolescent online intervention. As such, studies were heterogeneous in terms of both participants and methods. Because of inconsistent reporting of effect sizes across the studies, and wide variations in study design (e.g., RCT versus pre-post design), method, target of the interventions, and outcome measures used to assess change in symptoms, it was deemed inappropriate to calculate an average effect size via meta-analysis (Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care, 2017; Haidich, 2010). Effect sizes reported in Table 2 ranged from very small to large for between- and within-subjects effects.

Characteristics of interventions

In cases where the intervention was described in detail, summary data was collected around the characteristics of the interventions in terms of the frequency of module delivery, duration of the intervention, the content/activities/ format that comprised the intervention and any therapist contact that occurred as part of the intervention.

Stages of the intervention were most frequently described to participants as modules (12 studies), sessions (9 studies), or steps (2 studies). As such, for the purposes of Table 2 these have been termed modules. The average number of modules was 8.0 (SD=2.7), but these generally ranged from 4 to 14 modules. Additionally, two studies of the same intervention (Rice et al., 2018; Santeseban- Echarri et al., 2017) reported a large number (56) of optional steps for participants that were shorter in duration (approximately 20 minutes), which diverged significantly from the other studies identified as was not included in the average calculation. Frequency of module delivery also varied widely, from 4 times per week to fortnightly, with the majority requiring one module per week to be completed by participants. Duration of modules ranged from 10 to 90 minutes, excluding in-between module homework, and the average length of intervention was 7.6 weeks (SD=2.6).

Table 3 provides a descriptive summary of the various components and features included in the interventions. It should be noted that these represent a summary of the information available, and interventions varied in how many of these components they included.

Role of the therapist

Information was also extracted regarding therapist/moderator contact with 68% (28 out of the 41) of studies reporting on interventions including at least some contact with a therapist/moderator/facilitator. Three studies did not provide this information and one intervention was described as self-help but participants were concurrently receiving regular face-to-face treatment alongside the intervention.

The role of the therapists/moderator/contact person varied widely and included: psychologists, clinical psychologists, moderators, facilitators, school wellbeing staff, nurses, psychology students in final year of placement, research assistants, mental health clinicians and lived experience peers.

Contact with the therapist usually occurred via email/messaging, phone or in-person and varied in frequency. Some interventions had initial consultations with an option for contact if needed. Others had weekly contact following the completion of the module (generally around 15 minutes in length). More intensive interventions included completion of module along with the therapist but this was rare. The most common procedure was for the client to complete the module individually with the option to ask the therapist a question. The client would then receive a follow-up call/email with feedback from therapist once module was complete. For the most part, this comprised weekly therapist/moderator contact.

The role of the therapist/moderator also varied widely among interventions. Roles and tasks included: providing feedback on homework and session activities; answering questions; providing encouragement and motivation (e.g., congratulating client for completing module); reminders and follow-up for non-completion of tasks/activities/modules; checking in at different time points (sometimes after conclusion of intervention) to see if/how skills were applied; assistance with applying skills; summarising content for client, encourage homework and practicing skills; resolve/ work through any challenges.

Other aspects of interventions

Other common and notable aspects of interventions included: Therapists/moderators generally had access to the client workbooks and activities in order to provide feedback; client often had option whether to contact via phone or email; in some cases (with permission of client) therapist contact details were provided to parents; some interventions required specific training of therapists in the online intervention; some interventions provided therapists with templates, set criteria, or protocols to guide protocols to guide communication with the client.

Discussion

There is an urgent need to develop and test empirically based online interventions for personality dysfunction in adolescence. This research used scoping and rapid review methodology to identify characteristics that may maximise the effectiveness of online intervention for adolescents, but no studies or interventions could be identified targeting personality disorder specifically. A scoping review identified 32 online mental health programs relevant to adolescents and young people with personality disorder or emerging personality disorder symptoms, including anxiety and depression (see: Chanen et al., 2007; Ha et al., 2014). A rapid review of the empirical literature uncovered 41 studies that targeted symptoms that may present alongside personality disorder or emerging personality disorder (e.g., depression, suicidal ideation, self-harm) - but again none of these directly targeted personality disorder. The research provides an indication of the necessity of developing online interventions targeted to the prevention and treatment of personality disorder or emerging personality disorder in adolescence. While there were no personality disorder-specific interventions, our results have implications for the development of these interventions and should be used to aid adolescents in accessing treatment which may be otherwise unavailable. This is particularly relevant to the current global COVID-19 pandemic due to the emergence of a situation where access to face-to-face therapy has become increasingly limited.

Despite no specific programs or interventions targeting personality disorder, integration of information from the empirical and scoping reviews made it possible to isolate common characteristics of the interventions which may be beneficial to integrate in future interventions that seek to target personality disorder or emerging personality disorder for adolescents. These common characteristics cover the type, delivery and components that are thought to increase success and improve adherence to interventions. Common characteristics include:

Interventions comprise of a number of modules, steps, sessions or lessons - approximately 7 or 8 - delivered weekly (over approximately 10 weeks);

Interventions utilise sequential presentation of modules - making new modules available to the client only when they have completed the previous one (e.g., Dear et al., 2018; “Mindspot Mood Mechanic Course”, 2020);

Interventions include homework, workbooks or diaries between modules in order to promote understanding, record practicing of skills, and prompt subsequent discussions with their therapist around issues they found challenging (e.g., Bjureberg et al., 2018; “Chilled Out Online,” 2020);

Interventions provide an option to connect with a therapist either via phone, email/messaging or face to face. Therapists monitor and provide feedback on activities/ homework, answer questions, assist the client to overcome challenges, provide reminders to complete homework/activities, and motivate adherence and completion of the intervention. Many successful interventions emphasised the importance of regular (albeit brief) therapist contact (e.g., Bjureberg et al., 2018; Dear et al., 2018; Gladstone et al., 2015; Hetrick et al., 2017; Lindqvist et al., 2020; Santesteban- Echarri et al., 2017; Spence et al., 2011);

Inclusion of screening/assessment of clients prior to them being given access to modules (via phone or face to face), so the client has initial information about the intervention and so that the appropriateness of the intervention for that client can be gauged (e.g., Alvarez- Jimenez et al., 2013; “myCompass,” 2020; “Mindspot Mood Mechanic Course”, 2020);

The use of characters, cartoons or avatars with different personalities/difficulties to illustrate symptoms and demonstrate skills (e.g., Bobier, Stasiak, Mountford, Merry, & Moor, 2013; “Super Better”, 2020; “Sparx”, 2009; “This Way Up TeenStrong”, 2020);

A section for resources/factsheets/skills that can be accessed at any time and are collected as the client progresses through modules (e.g., March, Spence, Donovan, & Kenardy, 2018; “The BRAVE program”, 2020; “Mindshift CBT”, 2019);

Modules may include short videos providing information and details around skills and then interactive activities to assist the client in practicing the skills (e.g., Hetrick et al., 2017; Lindqvist et al., 2020; Richards, Cogan, Hacker, Amin, & Beoing, 2004; “Beating the blues,” n.d.);

Sections where clients can create a personalised safety plan for times of crisis (e.g., selects and lists support people; records preferred relaxation activities that work for them in times of distress). It is important that this safety plan can be accessed by the client at any time (e.g., Bjureberg et al., 2018);

A method to allow the client to track their progress (e.g., via assessment of symptoms, quizzes, therapist feedback) and a certificate of completion once the intervention has concluded (e.g., Stjerneklar, Hougaard, Nielsen, Gaardsvig, & Thastum, 2018; “moodgym”, 2020; “E couch”, 2018);

Including parent workbooks or parent interventions (often with fewer modules than those for clients). This allows parents to learn skills and understand their child’s difficulties, as well as assist them in motivating their child to continue with the intervention (e.g., Waite, Marshall, & Creswell, 2019; “This Way Up Teenstrong,” 2020; “Chilled Out Online,” 2020)

A specific component reviewed within interventions and programs was therapist contact. In phase one, only a limited number of programs had the addition of therapist contact. It should be noted that phase one was a scoping review designed to gain understanding on the scope of available programs, and no evaluation on the efficacy of these programs was conducted. It is of note that there were limited options for therapist contact as previous research has indicated that programs with concurrent therapist contact have highest completion rates, with self-guided phone applications having the lowest completion rates (Struthers et al., 2015). Therefore, there is an imperative for more evidence-based online programs to be developed. However, phase two supported evidence on therapist involvement, with well over half the studies including at least some therapist contact. One study that evaluated therapist contact found that young people were satisfied with therapist support, finding it motivational and helpful and when provided with the option for additional contact, all participants accepted it (Silfvernagel, Gren-Landell, Emanuelsson, Carlbring, & Andersson, 2015). Another study compared an intervention with either a self-guided or therapist-guided component and found that while both had significant improvements, satisfaction with the intervention among young people was higher when it was clinician-guided (Dear et al., 2018). Previous reviews indicate the benefits of therapist or supervisor support either via phone, email, teleconferencing or in-person when adolescents and young people are engaging in online therapy and has been linked to better engagement and adherence, as well as intervention outcomes (Clark et al., 2015; Struthers et al., 2015). Specific to the COVID-19 pandemic, a recent review found that although there are limitations, telepsychotherapy used when face-to-face therapy is not available is found to be effective for adults (Poletti et al., 2020) and given the increasing engagement of adolescents in digital technologies, it is likely telepsychotherapy will be similarly effective (Montague et al., 2015). Our study specifically excluded online platforms which replaced face-to-face therapy through an online platform with no interactive intervention component in order to meet the aim of identifying specific online interventions, however the future research could aim to identify and evaluate telepsychotherapy.

This review was conducted prior to COVID-19 being declared a pandemic and the isolation and health restrictions that followed reducing access to face-to-face interventions. It is likely that following this declaration, new online interventions for adolescents were developed to address the urgency of accessibility which this study was not able to review. However, it was important to identify the pre-existing evidence to understand what may be necessary and effective to include in the development of new programs and interventions. This research has implications extending to provision of more cost-effective, accessible prevention and treatment of personality disorder or emerging personality disorder symptoms in adolescence, particularly to those who experience added barriers such as living in remote locations, and when face-to-face access is limited, including during the time of COVID-19.

Personality disorders are complex mental illnesses that are costly for both the health sector and the individual. Enriching understanding of components of successful prevention and treatment, and developing more accessible treatments for personality disorder that can be delivered early in the symptom trajectory has been recognised as a national mental health priority area in Australia (NHMRC, 2012). Given the effect that the COVID-19 global pandemic has had on mental illness risk in the general population (e.g., Serafini et al., 2020) and individuals with pre-existing mental health conditions and personality disorders specifically (Álvaro et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2020) providing effective online therapy has clear implications for mitigating symptom progression and improving access for those who are geographically isolated. As such, flow on research generated by this review has potential to impact health and wellbeing for adolescents with personality disorder or emerging personality disorder symptoms, and their carers. Future research will integrate these results to develop and test a brief online intervention targeting personality disorder and emerging personality disorder symptoms in adolescence.

The common characteristics identified is supported by previous research which evaluates the effectiveness of online therapy for adolescent mental health. Skillsbased online interventions with specific sessions have been found to be effective for adolescent mental health (Clark et al., 2015) and human support elements and therapist support has been found to be valuable in the implementation of online therapies (Clark et al., 2015; Struthers et al., 2015). Further, research indicates that young people are increasingly engaged with technology and willing to engage in online psychotherapy however care still needs to be taken to ensure a collaboration between client and therapist and foster the therapeutic relationship (Montague et al., 2015).

While there is previous research on adolescent mental health interventions in online format, the research specific to personality disorders in adolescence is scarce. This makes it difficult to conclusively identify what may or may not be effective. However, research does indicate that developing evidence-based psychotherapy into online formats is effective for adolescents and young people (Clark et al., 2015; O’Dea et al., 2015). Therefore, integrating common elements of adolescent online interventions identified in this review, as well as evidence for effective psychotherapy for personality disorder may be beneficial in the development of new online interventions which target personality disorder, or emerging personality disorder symptoms in adolescents. Evidence suggests that therapeutic approaches traditionally applied to personality disorder populations, like dialectical behaviour therapy (DBT), can be effectively delivered using online formats (Wilks et al., 2018). Whilst online therapies for conditions related to personality disorder may inform new approaches, it is recommended that empirically supported treatment components specific to personality disorder treatment are incorporated into new online therapies. Since personality disorders can be understood as a function of relationships between self and other, it is recommended that a relational model of care is incorporated into approach (Grenyer, 2014; Townsend, Haselton, Marceau, Gray, & Grenyer, 2018). This model emphasises the need to understand symptoms of personality disorder as stemming from problematic and dysfunctional relationship styles that have developed over time. The Relational Model is closely linked to attachment theory (Bowlby, 1979) which posits that models of the self and others are formed via early interactions with significant others, and these impact personality organisation, self-worth, and interpersonal relationships throughout the lifespan. Attachment is highly relevant to both development and treatment of personality disorders (e.g., Fonagy, Target, & Gergely, 2000), as it has been shown to affect in therapy variables (e.g., the therapeutic alliance; Diener & Monroe, 2011). Furthermore, changes towards a more secure attachment representations have been demonstrated to be predictive of recovery across many mental disorders (Levy, Kivity, Johnson, & Gooch, 2018). The Relational Model expands on attachment theory, incorporating multiple relationships relevant to adolescents: their relationship to self, the clinician, family, peers and the school and community (Townsend et al., 2018). Psychological education and connection with family members, carers, schools and health services should therefore be considered within new approaches for personality disorder. Other intervention components may address factors specific to personality disorder, like emotional dysregulation, rejection sensitivity and mentalisation problems, to provide a more targeted treatment approach (Grenyer, 2014).

Recommendations emerging from the literature and scoping review have clear implications for future research and development of interventions. Despite this, there were some limitations to this methodology, particularly in terms of the restricted time frame of the scoping and rapid review. Whilst rapid review methodology is acknowledged to be a robust method of synthesising data (Abou-Setta et al., 2016; Haby et al., 2016) a more thorough meta-analysis including effect sizes for each intervention, would provide useful information. This was outside of the scope of the present research but would be an important next step in demonstrating the efficacy of different types of online interventions for adolescents with personality disorder or emerging personality disorder symptoms. Currently the limited amount of literature around this specific topic precludes the ability to conduct meta-analyses. Future research should utilise randomised controlled trial methodology to evaluate new online therapies and interventions and should also seek to provide quantitative data synthesis from these studies. Limitations of the scoping review include the time sensitive nature, and location-restrictions of search algorithms (on Google, for example). It is possible that a greater number of interventions for adolescents exist that were not included, but efforts were made to identify each relevant source of data (e.g., stringent inclusion/ exclusion criteria).

Since the reviews were conducted in early 2020 and prior to the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic by WHO on the 11th March 2020 (for a full timeline of COVID-19 see: WHO, 2020b), the full impact of COVID-19 had not yet been felt in many parts of the world, so it is possible that a greater number of relevant studies have been published since then. Due to the currently unfolding and unpredictable nature of the pandemic, and the evident urgency of the need for online interventions, our study is valuable in providing an indication of what existed prior to the pandemic and has implications for the development of emerging and effective online interventions. However, future research should endeavour to identify programs and interventions that may have been developed during, or due to, the COVID-19 pandemic, and identify the characteristics and evaluate the effectiveness of these. Some studies also included participants below the age of 10, and over the age of 19, which is outside the WHO (2020a) definition of adolescence (10 to 19 years). Given the scarcity of studies, and the value of the data they provided, these were not excluded, but this limits the specificity of findings to adolescents. Finally, the time limited nature of rapid reviews means that a more thorough examination of each article included and the risk of bias inherent within those articles was not possible. There were a multitude of factors and components of each intervention that were beyond the scope of this review, but may provide additional useful information, so future research may examine more intricate aspects of the online interventions.

Overall, results of this study indicated that while many online interventions for adolescents targeting depression and anxiety exist, no studies have directly evaluated an intervention for adolescents with personality disorder or showing signs and symptoms of emerging personality disorder. This research highlights the need to develop new evidence-based interventions that can improve access to treatment for adolescents, particularly relevant during the time of the COVID-19 pandemic when face-to-face therapies are not easily accessible. This study and recommendations generated highlight characteristics of other online treatments that may be generalised to prevention and treatment of personality disorder, and thus represent an initial step towards the development of new interventions for adolescents experiencing these problems.

Table 1.

Summary of online interventions included in phase one scoping review.

| Intervention name | Publisher | Format | Country of development | Participants | Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIMhi Stay strong app | Menzies School of Health research | App | Australia | Adults: 18 + yearsc | Mental health and wellbeing for Indigenous Australians |

| Anxiety Coach | Mayo Clinic | App | United States of America | Children and Adolescents | Anxiety |

| Anxiety Reliever | Anxiety Reliever LLC | App | United States of America | No age | Anxiety |

| Beating the blues | 365 Health Solutions Limited | Online program | United Kingdom | Adults: 18 + yearsc | Anxiety and depression |

| BetterBET | University of Carlifornia, Palo Alto University | Online program | United States of America | Adults: 18 + yearsc | Depression |

| Bite Back - mental fitness challenge | Black Dog Institute | Online program | Australia | Adolescents: 12-18 years | Resilience and wellbeing |

| The BRAVE program | Beyond Blue | Online program | Australia | Adolescents: 12-17 yearsb | Anxiety |

| Calm Harm app | Stem 4 | App | United Kingdom | Adolescents and adults: 13 + years | Self-harm |

| Chilled Out Online | Macquarie University | Online program | Australia | Adolescents: 13-17 years | Anxiety |

| Clear Fear app | Stem 4 | App | United Kingdom | Adolescents: 11-19 years | Anxiety |

| Dealing with Depression (DWD) | Centre for Applied Research in Mental Health and Addiction | Online program | Canada | Adolescents: 13-19 years | Depression |

| E-Coucha | e-hub Health | Online program | Australia | Adolescents and adults: 12 + years | Depression, anxiety, mental health |

| Kooth | Xenzone | App | United Kingdom | Adolescents: 11-18 years | Emotional Wellbeing |

| Living life to the full | Five areas Limited | Online program | United Kingdom | Adults: 18 + yearsc | Anxiety, Stress and depression |

| Mentalhealthonlinea | Swinburne University of Technology | Online program | Australia | Adults: 18 + yearsc | Generalised anxiety, depression |

| Mindshift CBT | Anxiety Canada | App | Canada | No age | Anxiety |

| MindSpot Indigenous Wellbeing course | MindSpot | Online program | Australia | Adults: 18 + yearsc | Indigenous Australians with symptoms of depression and anxiety |

| MindSpot Clinic Mood Mechanic Course | MindSpot | Online program | Australia | Young people: 18-25 years | Young adults with symptoms of depression and anxiety |

| Moodgym | ehub Health | Online program | Australia | Adolescents and adults: 16 + years | Anxiety and depression |

| MoodKit | Thrive Port | App | United States of America | Adults: 18 + yearsc | Mood improvement |

| MoodMission | MoodMission | App | Australia | No age | Low mood and anxiety |

| My Anxiety Plan for children and teens (MAP) | Anxiety Canada | Online program | Canada | Children and adolescents | Anxiety |

| My Compass | Black Dog Institute | Online program | Australia | No age | Mental Health |

| My Digital Health mental health and wellbeing coursesa | My Digital Health | App and Online program | Australia | Adults: 18 + yearsc | Depression, anxiety and mental health |

| SPARX | The University of Auckland | Online program | New Zealand | Young people | Mild to Moderate depression |

| Stress and anxiety in teenagers | National Health Service (NHS), Richards et al. | Online program | United Kingdom | Adolescents: 12-19 years | Stress and anxiety |

| SuperBetter | SuperBetter | App and Online program | United States of America | No age | Resilience and wellbeing |

| Thedesk | The University of Queensland | Online program | Australia | Tertiary students | Mental health and wellbeing |

| This Way Up adult mental health coursesa | St Vincent’s Hospital | App and Online program | Australia | Adolescents and adults: 16 + years | Depression, anxiety, stress |

| This Way Up TeenSTRONG | St Vincent’s Hospital | App and Online program | Australia | Adolescents: 12-17 years | Worry and sadness |

| WellMind | National Health Service (NHS) | App | United Kingdom | No age | Anxiety and depression |

| What’s Up | What’s Up, Tempra | App | Australia | No age | Depression, anxiety, anger, stress |

aPrograms offer several courses targeted towards different mental health concerns, or aspects of wellbeing; bThis program had several courses for different ages, the course designed for this age range was reviewed; cPrograms age target included young people aged 18-25 and were therefore included in review.

Table 2.

Summary of findings from rapid empirical literature review.

| Study | Country | Design | Participants | N | Type of intervention | Frequency/ duration | Therapist assistance | Outcomes/effect size if available |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvarez-Jimenez et at (2018) | Australia | Pilot study | Adolescents and young adults: 15-25 years | 14 | Strength based psychotherapy model based on Social Determination Theory for adolescents at high risk of developing psychosis | Unrestricted access | Therapist assisted: Phone, online messaging | Results indicated medium to large increases in personal strengths use (d = 0.7), mindfulness skills (d = 0.66), attachment (d = 0.7), guidance (d = 0.75), subjective wellbeing (d = 0.75). Participants displayed reliable improvement in depressive symptoms. |

| Anderson et al. (2012) | Australia | Randomised trial | Adolescents: 12-18 years | Face to face therapy condition n =38, internet condition n = 35 (Study 1); n=132 (Study 2) | CBT targeting anxiety | 10 sessions over 10 weeks | Therapist assisted (minimal email and phone contact) | Study 1 found no significant differences between groups on working alliance scores for adolescents (d = 0.15), but parent working alliance was stronger for face to face condition (d = 0.64) than internet condition. Study 2 demonstrated significant improvement in anxiety and global functioning for participants exposed to the online therapy (at 6 months follow up). |

| Bannink et al. (2014) | Netherlands | RCT | Adolescents: 15-16 years | Online intervention only n = 392; Online intervention with consultation n = 430; Control group n = 434 | Messages and information focussed on mental wellbeing generally | Single session (online intervention and consultation group only) | Therapist assisted: 45 minute consultation with option for further consultation if needed | Online intervention and online intervention with consultation groups reported better mental health status compared to control (d = 0.12). Adolescents at risk who were part of the online intervention with consultation group reported significantly better mental health status (d = 0.34) and quality of life (d = 0.37) at follow-up compared to adolescents as risk in the control group. |

| Bjureberg et al. (2018) | Sweden | Pilot Study | Adolescents: 13-17 years | 25 | Acceptance-based behavioural intervention therapy - targeting emotional regulation for non-suicidal self injury (NSSI) | 11 modules over 11 weeks | Weekly therapist feedback and assistance with activities; telephone contact | There was a large reduction in NSSI frequency pre- to post-treatment (d = 0.88); a medium reduction post-treatment to 3-month follow-up (d = .57); and no significant change from 3-month to 6-month follow up. Overall change in NSSI frequency from baseline to 6 month follow up was large (d = 1.36). Emotional dysregulation also decreased pre- to post- treatment (d = 0.75). |

| Bobier et al. (2013) | New Zealand | Feasibility and acceptability study | Adolescents: 16-18 years | 20 | Third-person fantasy based game designed around CBT principles targeting variety of mental health issues | 7 modules (30 minutes each) | Therapist assisted (inpatient facility) | Adherence and uptake of intervention was satisfactory. Facilitators of satisfaction for patients included the localised look and feel of program, self-paced nature, game design and ability to undertake intervention while in hospital. Barriers to satisfaction included the quality of graphics. One participant felt talking therapy was superior. |

| Calear et al. (2009) | Australia | Cluster RCT | Adolescents: 12-17 years | Intervention condition n = 563; waitlist control n = 914 | CBT targeting symptoms of anxiety/depression | 5 modules over 5 weeks | No therapist contact (teachers supervised at school) | Greater reduction in anxiety for intervention group compared to waitlist group post-intervention (d = 0.15); with similar pattern of results at 6 month follow up (d = 0.25). Depression scores were lower for male participants in intervention group compared to waitlist post-intervention (d = 0.43), but there was no significant difference for female participants. |

| Chapman et al. (2016) | UK | Feasibility study | Adolescents: 13-16 years | 11 | CBT intervention, mindfulness and self-regulation skills targeting anxiety and low mood | 7 levels over 7 weeks | Therapist assisted | Reductions in symptoms of anxiety and depression were shown for 4 of the 11 participants and one participant demonstrated clinically significant change. Parent ratings of depression and anxiety indicated that six participants showed reductions on these indices. Benefits reported by participants included: improving skills around negative thought recognition and relaxation; computer delivered intervention; game was relaxed and fun; promoted feelings of being understood. Areas for improvement noted by participants included: too much information/too complex; not age-appropriate; and the difficulty of short-term work. |

| de Voogd et al. (2018) | Netherlands | RCT | Adolescents: 11-19 years | Intervention n=134; Placebo n = 39 | Interpretation bias modification training targeting anxiety and depression | 8 sessions over approximately 4 weeks | No therapist assistance | Interpretation bias improved for the intervention group compared to the placebo group. There were no differences in depression, anxiety or emotional scores between intervention and placebo groups. |

| de Voogd, et al. (2016) | Netherlands | RCT | Adolescents: 11-18 years | Emotion working memory condition n = 129; Placebo n = 39 | Emotional working memory training targeting anxiety and depression | 12 sessions over 3 weeks | No therapist assistance | No significant differences in working memory capacity, anxiety or depression were evident between intervention and placebo groups. |

| Dear et al. (2018) | Australia | RCT | Adolescents and young adults: 18-24 years | Clinician guided group n= 110; self-guided group n= 107 | Transdiagnostic psychological principles and cognitive and behavioural skills to target anxiety and depression | 5 lessons over 5 weeks | Therapist assisted (telephone contact and feedback for clinician guided group only) | Both groups reported significant improvements (self-guided and therapist-guided work) with satisfaction slightly higher for clinician guided group. |

| Gladstone et al. (2014) | USA | No control study | Adolescents and young adults: 14-21 years | 83 | Cognitive-behavioural, humanistic, interpersonal approaches for depression | 14 modules | Therapist telephone contact | Participants demonstrated improvement in symptoms of depression and reductions in automatic negative thoughts from baseline to follow up. |

| Hetrick et al. (2017) | Australia | RCT | Adolescents: 13-19 years | Intervention group n = 26; Control group n = 24 | CBT for suicide-related behaviours | 8 modules over 10 weeks | Therapist contact via online message board | Suicide ideation scores decreased in the intervention group from baseline to 10 week follow up and from baseline to 22 week follow up but differences between groups were not statistically significant. Fewer suicide attempts were reported for the intervention group at follow up. |

| Hetrick et al. (2014) | Australia | Pilot study | Adolescents: 14-18 years | Pre-treatment n = 32; Post-treatment n = 21 | CBT for suicide-related behaviours | 8 modules over 8 weeks | Therapist contact via online message board | Problem solving improved from baseline to post-treatment with a large effect size (eta-squared = 0.96). Emotion focussed coping improved from baseline to post-treatment with a large effect size (eta-squared = 1.2) |

| Ip et al. (2016) | China | RCT | Adolescents: 13-17 years | Intervention group n = 123; control group n=127 | CBT targeting depression | 10 modules over approximately 8 months | No therapist assistance (except crisis intervention) | At 12 month follow-up the intervention group had greater reductions in depression symptoms with a medium effect size (d = 0.36). |

| Karbasi and Haratian (2018) | Iran | RCT | Adolescent females: 10-18 years | Intervention group n = 15; Control group n = 15 | Internet based CBT (iCBT) targeting anxiety | 7 stages over 3 months | Therapist email contact | Both control and ICBT groups had significantly lower anxiety scores at post-test. The ICBT group had significantly lower anxiety scores from pre-test to post-test compared to the control group. |

| Kramer et al. (2014) | Netherlands | RCT | Adolescents and young adults: 12-22 years | Intervention group n = 131; Waitlist group n = 132 | Solution-focussed brief therapy targeting depression | 5 sessions (1 hour) once a week | Therapist contact via online chat | Greater reduction in symptoms of depression for the intervention group compared to waitlist from baseline to 9 weeks with a small effect size (d = 0.18) and from baseline to 4.5 months with a large effect size (d = 0.79). For the intervention group, there was a large effect size for reduction in depression symptoms between baseline and 7.5 month follow up (d = 1.6). |

| Kruger et al. (2017) | USA | Phase II Clinical trial | Adolescents and young adults: 14-21 years | Motivational interviewing with intervention group n = 40; Brief advice with intervention group n = 43 | CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy, behavioural action, community resiliency approaches targeting depression | 14 modules | Therapist contact in person and via phone | All participants had improved levels of automatic negative thoughts and emotional impairment over time but no differences in perceived social support from family and friends. Change was not evident in first 6 weeks but there was a marked decrease in automatic negative thoughts from 6 weeks at 2.5 year follow up. |

| Kuosmanen et al. (2018) | Ireland | RCT - but reporting on implementation study findings | Adolescents and young adults: 15-20 years | 28 | CBT-based self-help intervention for mild to moderate depression | 7 levels (approximately 30 minutes each) | No therapist assistance (staff monitored at point of delivery) | Participant feedback indicated that less than half liked the look/ thought it was fun and less than a third would recommend it to a friend. This was attributed to lengthy modules, technical problems and a perceived lack of positive focus. However the majority of participants found the program easy to use and understand. Individuals at high risk of depression rated it more relevant and useful than those at low risk. |

| Kurkl et al. (2018) | Finland | Qualitative descriptive study | Psychiatric nurses treating adolescents | 9 | Internet-based support system for outpatient psychiatric care targeting depression | 6 topics over 6 weeks | No therapist assistance (nurse assisted) | Psychiatric nurses perceived intervention positively but had difficulties encouraging adolescents to participate. They perceived technology to be useful in interventions, but felt that a lack of support made it difficult to implement the intervention, which was not easily integrated into regular care. |

| Lillevoll et al. (2014) | Norway | RCT | Adolescents and young adults: 15-20 years | Control group n = 180; Intervention with no reminder n = 176; Intervention with standard reminders n = 176; Intervention with tailored reminders n = 175 | CBT for symptoms of depression | 5 modules over 6 weeks | No therapist contact except email reminders delivered according to condition | No significant changes in self-esteem and depression symptoms were found (possibly attributable to drop out after Module 2). Tailored or standard emails did not differ in effectively prompting use of the intervention. |

| Lindqvist et al. (2020) | UK | RCT | Adolescents: 15-18 years | Intervention group n = 34, Control group n = 38 | Affect-focussed psychodynamic therapy targeting awareness, experience and expression of emotions | 8 modules over 8 weeks | Therapist online feedback, instant messaging and 30 minute chat each week | Large between groups effect size (intervention to control) for primary depression symptoms measures (d = 0.82), anxiety measures (d = 0.78), emotion regulation (d = 0.97), and self-compassion (d = 0.65) |

| March et al. (2018) | Australia | Feasibility and acceptability study | Children and adolescents: 7-17 years | 4425 | Interactive web-based CBT targeting anxiety | 10 sessions over 10 weeks | No therapist support | Anxiety scores for adolescent version of the intervention improved significantly between baseline and final session (d = 0.65). Greater improvements in anxiety were associated with a greater number of completed sessions but participants still showed improvement irrespective of the amount of sessions taken. |

| Neil et al. (2009) | Australia | Comparison study | Adolescents: 13-19 years | School sample n = 1000; Community sample n = 7207 | CBT targeting anxiety and depression | 5 modules over 5 weeks | No therapist support | Adolescents in the school-based sample completed significantly more exercises than those in community sample. Setting (school), gender (female) predicted greater adherence. |

| O'Kearney et al. (2009) | Australia | Controlled trial | Adolescent females: 15-16 years | Intervention group n = 67; Control n = 90 | CBT targeting depression and coping skills | 5 modules over 6 weeks (self-paced) | No therapist support | Immediately following intervention there were small, non-significant effects for depression scores for the total sample (d = 0.19) and for the group with high initial depression scores (d = 0.12). At follow-up there was a significant moderate effect on depression scores for the total sample (d = 0.46) and a moderate to large significant effect for the group with high depression scores at intake (d = 0.92). |

| Perry et al. (2017) | Australia | Cluster RCT | Adolescents: 16-17 years | Intervention group n = 242; Control n = 298 | Interactive program using format of a fantasy game providing CBT skills to target depression, anxiety and stress | 7 modules over 5-7 weeks | No therapist support | Participants in the intervention condition experienced small, significantly greater reductions in depression scores (compared to control condition) at post intervention (d = 0.29); and 6-month follow-up (d = 0.21). There was a small, non-significant effect (intervention to control) at 18-month follow up (d = 0.33). |

| Redzic et al. (2014) | USA | Development and evaluation study | Adolescents: 14-15 years | Sample 1 n = 158; Sample 2n=132 | Positive psychology and CBT approaches aimed at prevention of depression | 8 sessions over 8 weeks | Therapist monitoring via discussion board | After program was improved (i.e., when comparing sample 1 to sample 2), sample 2 found the intervention significantly more helpful (d = 1.2), interesting (d = 1.1) and more fun (d = 1.1) than sample 1. |

| Rice et al. (2018) | Australia | Pilot study | Adolescents and young adults: 15-25 years | 42 | Positive psychology, mindfulness and strength-based intervention targeting symptoms of depression and improved social functioning | 56 (optional) therapy steps, each 20 minutes long and selected according to clients' needs | Therapist moderators (and also peer support) | Change between baseline and 12 week follow up indicated significant improvement, with small-moderate effect, in depression scores (d = 0.45). 5 participants met criteria for MDD at baseline and were all in remission at 12 weeks follow up. |

| Richards et al. (2016) | USA | RCT | Adolescents and young adults: 14-21 years | 44 | Behavioural activation CBT, interpersonal psychotherapy and community resilience approaches targeting depression | 14 modules | Brief therapist contact at intake and follow up and social worker contact via phone | Participants reported significant decreases in depression symptoms using from baseline to 2.5 years post intervention. There were no significant changes in self-harm risk assessment or serious thoughts of suicide at 2.5 year follow up (possibly due to small number having any at baseline) |

| Rickhi et al. (2015) | Canada | Parallel group, randomized controlled clinical pilot trial | Adolescents and young adults: 13-24 years | Intervention group n = 31; Control n = 31 | Exploration of spiritually informed principles (e.g. forgiveness, gratitude, compassion) targeting depression | 8 modules over 8 weeks | No therapist contact (but participants could continue their regular treatment) | Average depression scores significantly decreased from baseline to 8 weeks and there was also a significant decrease from week 16 to week 24 for the intervention group. The difference between baseline and week 8 was not significant for the waitlist group, but after intervention (week 16) score significantly decreased and this trend continued week 16 to week 24. |

| Robinson et al. (2016) | Australia | Pilot study (pre-post design) | Adolescents: 14-18 years | 21 | Internet-based CBT targeted at young people experiencing suicidal ideation | 8 modules over 8 weeks | Therapist assisted (in person and online) | Participants experienced significant decreases in suicide ideation, with a moderate effect size (d = 0.66), depressive symptoms, with small-moderate-effect sizes (d = 0.60; d = 0.48), and hopelessness, with a small effect size (d = 0.40). |

| Robinson et al. (2014) | Australia | Pilot study (pre-post design) and acceptability study | Adolescents: 14-18 years | 21 | Internet-based CBT targeted at young people experiencing suicidal ideation | 8 modules over 8 weeks | Therapist assisted (in person and online) | Study purpose was to examine acceptability. Suicide ideation and distress remained the same or decreased over the course of each module. One participant found programme moderately distressing, four found it mildly distressing and 16 reported they did not find it anyway distressing. |

| Santesteban-Echarri et al. (2017) | Australia | Qualitative post-intervention evaluation (semi-structured interviews and focus groups) | Adolescents and young adults: 15-25 years | 38 | Positive psychology, mindfulness, CBT and strength-based approach targeting depression | 56 (optional) therapy steps, each 20 minutes long and selected according to clients' needs | Therapist moderators (and also peer support) | At 12 week follow up, all participants found the site helpful and said they would recommend it; 26% of participants reported therapy content as most liked component; 47% of participants reported social networking as most liked component. |

| Silfvernagel et al. (2015) | Sweden | Pilot effectiveness study | Adolescents: 15-19 years | 11 | CBT targeting anxiety and possible comorbid depression | 6-9 modules over 6-18 weeks (depending on client) | Therapist assisted (face to face, phone, email) | Scores pre-post treatment indicated large effect sizes and significant decreases in anxiety scores (d = 2.51); fewer negative thoughts (d = 1.15); increases in psychological wellbeing (d = 1.29) and decreases in depressive symptoms (d= 1.51). |

| Smith et al. (2015) | UK | RCT (intervention and waitlist control) | Adolescents: 12-16 years | Intervention condition n = 55; Waitlist control condition n = 57 | Computerised CBT (cCBT) program targeting mild to moderate depression | 8 sessions over 8 weeks | No therapist assistance (school setting) | From baseline to post-intervention self-reported depression scores were lower for intervention (compared to waitlist) group, with a larger effect size (d = 0.82) and anxiety scores were also lower, with a small effect size (d = 0.41). |

| Spence et al. (2011) | Australia | RCT | Adolescents: 12-18 years | Internet intervention condition n = 44; Clinic intervention condition n = 44; Waitlist condition n = 27 | CBT targeting anxiety | 10 sessions over 10 weeks | Therapist assisted | Rate of session completion was significantly slower in the online intervention compared to clinic intervention, (eta-squared = 0.15). The online and clinical groups evidenced significantly lower clinical severity (anxiety) ratings from baseline to 12 weeks (d = 2.12 and d = 3.42 respectively), and improved global assessment scores (d = 1.56 and d = 2.11 respectively). The waitlist condition showed no significant change on these two measures. Overall, there was no significant difference between online and clinic groups in mean number of sessions completed but the online group had a significantly lower proportion of participants complete all sessions. |

| Stjerneklar et al. (2018) | Denmark | Feasibility study | Adolescents: 13-17 years | 6 | CBT targeting anxiety | 8 modules over 12 weeks | Therapist assisted (phone and feedback on worksheets) | Participants evidenced significant decreases in clinical severity ratings of anxiety pre to post intervention (d = 1.36) and in anxiety symptoms pre to post intervention (d = 0.45). Worsening symptoms, with a small effect size were reported at post to follow-up time point (d = 0.28). |

| Tillfors et al. (2011) | Sweden | RCT (intervention and waitlist control) | Adolescent and young adults: 15-21 years | Intervention condition n =10; Waitlist condition n = 9 | CBT self-help manual targeting social anxiety | 9 modules over 9 weeks | Therapist assisted (email and phone) | Pre-post analyses indicated that the intervention group reported significantly lower anxiety (d = 1.47) and depression scores (d = 1.39) compared to the waitlist condition but there was no significant difference in quality of life scores. |

| Topooco et al. (2018) | Sweden | RCT | Adolescents: 15-19 years. | Intervention condition n = 33, Control condition n = 37 | Internet-based CBT targeting depression | 8 modules over 8 weeks | Therapist assisted | Pre-post analyses indicated a significant improvement for intervention condition participants compared to controls on depression (d = 0.71) and self-efficacy (d = 1.33) but no significant differences in satisfaction with life and other measures of anxiety/depression. |

| Topper et al. (2017) | The Netherlands | RCT | Adolescents and young adults:15-22 years | Group intervention n = 82; Internet intervention n = 84; Waitlist control n = 85 | Modified rumination focussed CBT to target excessive worry and rumination | 6 sessions over 6 weeks | Therapist assisted | Pre-post analyses indicated that the internet and group intervention conditions evidenced significant reductions in repetitive negative thinking (d = 0.79 and d = 0.98 respectively) and depressive symptoms (d = 0.51 and d = 0.80 respectively). The waitlist control group showed no significant differences on these measures. |

| van der Zanden et al. (2012) | The Netherlands | RCT | Adolescents and young adults: 16-25 years. | Intervention condition n = 121; Control condition n = 123 | Structured CBT targeting depression | 6 sessions over 6 weeks | Therapist assisted | Significantly greater improvement was demonstrated for the intervention group compared to the control group: in depression symptoms (d = 0.94), anxiety symptoms (d = 0.49) and mastery of control (d = 0.44) during the baseline to 12 week time period. |

| Waite et al. (2019) | UK | RCT | Adolescents: 13-18 years | Intervention condition n = 30; Waitlist condition n = 30 | CBT targeting anxiety | 10 sessions over 10 weeks with 2 booster sessions | Therapist assisted | There was no significant difference between groups in post-treatment anxiety diagnostic status. There was a significant difference in global clinical improvement, with the intervention group showing greater improvement than the waitlist group. |

Note: Adolescents were classified as individuals aged 10-19 years (WHO, 2020a), children were those under 10 years, and young adults were aged 20-25 years. RCT, randomised controlled trial; CBT, cognitive behaviour therapy; MDD, major depressive disorder.

Table 3.

Summary of intervention components and features.

| Component/Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Information | • Presented using text, audio or video |

| Real life case examples (age appropriate) | • Presented via text, videos (either interviews or actors), vignettes, cartoons |

| • Typically used to depict/normalise common symptoms or experiences | |

| Homework | • Set at the end of the module and based on the information given in the module |

| • Usually to be completed before following module is accessed | |

| • At the beginning of subsequent module participants were often asked to either reflect on homework or input what they did | |

| • Often required the client to personalise homework (e.g., apply skill in a certain situation) | |

| • Sometimes included a measure of mood or other assessment | |

| Demonstration videos | • Demonstrations around how to use a skill/strategy |

| • Video diaries | |

| Worksheets and resources | • Either completed online or downloadable and sent via email to therapist |