Abstract

Objectives: Creating functional small-diameter tissue-engineered blood vessels has not been successful to date. Moreover, the processes underlying the in vivo remodeling of these grafts and the fate of cells seeded onto scaffolds remain unclear. Here we addressed these unmet scientific needs by using intravital molecular imaging to monitor the development of tissue-engineered vascular grafts (TEVG) implanted in mouse carotid artery.

Methods and Results: Green fluorescent protein–labeled human bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells and cord blood–derived endothelial progenitor cells were seeded on polyglycolic acid–poly-L-lactic acid scaffolds to construct small-caliber TEVG that were subsequently implanted in the carotid artery position of nude mice (n = 9). Mice were injected with near-infrared agents and imaged using intravital fluorescence microscope at 0, 7, and 35 days to validate in vivo the TEVG remodeling capability (Prosense680; VisEn, Woburn, MA) and patency (Angiosense750; VisEn). Imaging coregistered strong proteolytic activity and blood flow through anastomoses at both 7 and 35 days postimplantation. In addition, image analyses showed green fluorescent protein signal produced from mesenchymal stem cell up to 35 days postimplantation. Comprehensive correlative histopathological analyses corroborated intravital imaging findings.

Conclusions: Multispectral imaging offers simultaneous characterization of in vivo remodeling enzyme activity, functionality, and cell fate of viable small-caliber TEVG.

Introduction

An estimated 80,000 patients per year in the United States alone are not able to undergo coronary artery bypass grafting due to lack of suitable autologous vessels and poor function of currently available small-diameter synthetic vascular grafts.1 Current synthetic grafts, made of nondegradable synthetic materials, have been used as vascular conduits in cardiovascular surgery. However, the small-caliber grafts have shown shortcomings, including thrombus formation resulting in poor patency rates, infection, and lack of growth and remodeling potential.2 Small-caliber tissue-engineered vascular grafts (TEVGs) are being developed to overcome these limitations to create living autologous structures that are biocompatible and tailor-made, and that may exhibit the capacity to grow and remodel.3

A common approach begins with a biodegradable synthetic preshaped carrier or scaffold,4 formed like an artery, which is seeded with cells.5,6 This scaffold functions as a temporary matrix for cell support and anchorage until seeded cells produce their own extracellular matrix proteins. Many differentiated and progenitor cell types have been utilized for cell seeding: autologous endothelial progenitor cells (EPCs) and bone marrow–derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) have been utilized in this report and others,7 as they provide antithrombotic and extracellular matrix–producing functions, respectively, thereby resembling the native cell types found in a small-diameter artery.6,8,9 After an in vitro stage of tissue-engineered construct conditioning,10 the vascular construct can be implanted, followed by an in vivo stage of scaffold degradation and tissue remodeling intended to recapitulate normal tissue architecture and function.11 Although the functional feasibility of using TEVGs has been established,5,12 the mechanisms underlying formation of neovascular tissue and the remodeling of these grafts remain unclear.

Molecular imaging techniques have been used to investigate a number of different biological processes in vivo.13,14 Remodeling of neovascular tissue is mirrored by the degradation and synthesis of extracellular matrix and has shown to be largely mediated by matrix-degrading enzymes (matrix metalloproteinases [e.g., MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-13] and cysteine proteases [e.g., cathepsins S, K, and B]). Activated vascular cells overexpress MMPs and cathepsins, which, depending on the experimental or clinical scenario, may represent ongoing tissue development, remodeling, or disease progression.15,16 Using molecular imaging approaches, we recently detected endothelial cell activation, MMP, and cathepsin activity in normal and atherosclerotic mouse aortas and aortic valves.15,17 Current imaging modalities are able to detect in vivo expression and activity of molecules responsible for vascular remodeling and can monitor remodeling of native vascular tissue in individual patients.18,19

Considerable research in the field of tissue engineering has relied on using large animal models;20,21 which are intrinsically limited by the lack of genetically modified strains resulting in an inability to investigate tissue engineering (TE) applications of human-derived cell sources. Several studies have also demonstrated the feasibility of utilizing immunodeficient mice as a reliable tool to study small-caliber TEVGs.22–24 However, these studies have not addressed important questions regarding the late fate of engrafted cells and in vivo TEVG remodeling over time. A recent report used magnetic resonance imaging to monitor TEVGs seeded with iron-oxide nanoparticle–labeled cells.25 While this study provided important functional and anatomical information, it did not offer biological information at the cellular and molecular levels.

The inability to understand real-time dynamic remodeling processes and cellular changes in tissue engineered structures accounts for the limited knowledge in the field. In the present study, we used a small animal model and different imaging tools to address the specific questions concerning TEVG maturation in vivo. We aimed to investigate the dynamic remodeling capability of TEVGs by observing in vivo proteolytic enzyme activity otherwise undetectable by conventional imaging modalities. This method additionally offers the advantage of data collection in real time, without animal sacrifice. The secondary goal of this study was to trace in vivo the fate of engrafted cells. The results of the present study provide new insights into biology of implanted TEVGs and may aid in the exploration of novel diagnostic imaging strategies.

Materials and Methods

Study design

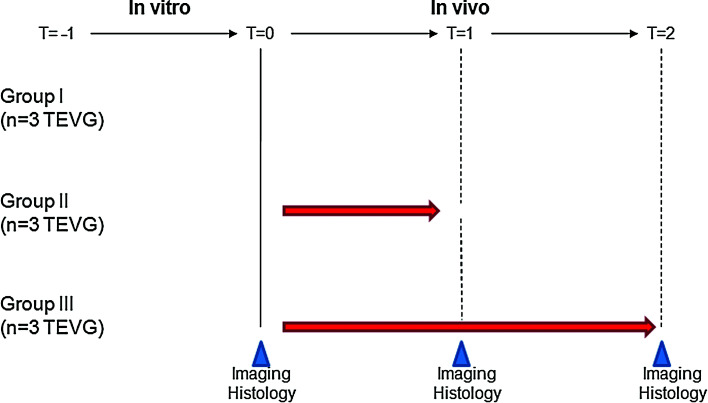

TEVGs (1 mm diameter) were made from 50% polyglycolic acid (PGA), 50% poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) nonwoven scaffolds, seeded with green fluorescent protein (GFP)–labeled human bone marrow–derived MSCs and EPCs. They were subsequently implanted into carotid arteries of nude mice (n = 9) and evaluated using intravital molecular imaging and histological approaches (Fig. 1). To target key molecular processes involved in tissue remodeling of implanted grafts, we used Prosense680 (VisEn, Woburn, MA) to image cathepsin protease activity. Intravital Microscopy (IV100; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was performed postoperative follow-up on mice with implanted grafts, who were anesthetized with 2% isofluorane anesthesia at the time of implantation (n = 3) and after 7 (n = 3) and 35 (n = 3) days postimplantation. After imaging, mice were euthanized and the grafts were explanted for histological evaluation. All experimental procedures were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Children's Hospital.

FIG. 1.

Study design. In vitro phase—T = −1: cell isolation, tissue-engineered vascular construct creation. In vivo phase—T = 0: preimplantation; T = 1: 7 days; T = 2: 35 days postimplantation. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Tissue engineering of vascular graft

Cells

Human MSCs were isolated from the mononuclear cell fraction of a 25 mL commercially available human bone marrow sample (Lonza, Walkersville, MD).26 Cells were seeded on 1% gelatin–coated tissue culture plates using endothelial growth medium (EGM-2) (except for hydrocortisone, vascular endothelial growth factor, beta fibroblast growth factor [βFGF], and heparin; Lonza), 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1× glutamine–penicillin–streptomycin (GPS; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and 15% autologous plasma. Unbound cells were removed at 48 h, and the bound cell fraction maintained in culture until 70% confluence using MSC medium: EGM-2 (except for hydrocortisone, vascular endothelial growth factor, βFGF, and heparin), 20% FBS, and 1× GPS. Thereafter, MSCs were subcultured on fibronectin-coated (1 μg/cm2; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) plates using MSC medium. MSCs between passages 4 and 9 were used for all the experiments. The characterization of the MSCs was performed as described in previous studies.26,27 The Harvard Committee on Microbiological Safety approved a protocol to work with human bone marrow–derived MSCs.

Retroviral transduction of MSCs

GFP-labeled cells were generated by retroviral infection with a pMX-GFP vector using a modified protocol from Kitamura et al.28 Briefly, retroviral supernatant from HEK 293T cells transfected with Fugene reagent was harvested, and MSCs (1 × 106 cells) were then incubated with 5 mL of virus stock for 6 h in the presence of 8 μg/mL polybrene. GFP-expressing cells were sorted by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), expanded under routine conditions, and used for in vivo experiments.

Isolation and culture of EPCs

Human umbilical cord blood was obtained from the Brigham and Women's Hospital in accordance with an Institutional Review Board–approved protocol. EPCs were isolated from the mononuclear cell fraction of cord blood samples, and purified using CD31-coated magnetic beads as previously described.29 EPCs were subcultured on fibronectin-coated plates using EPC medium: EGM-2 (except for hydrocortisone) supplemented with 20% FBS (Hyclone), 1× GPS. EPCs between passages 5 and 7 were used for all the experiments.

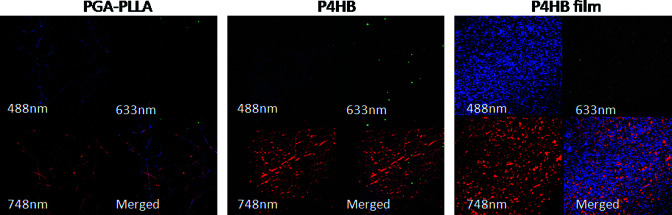

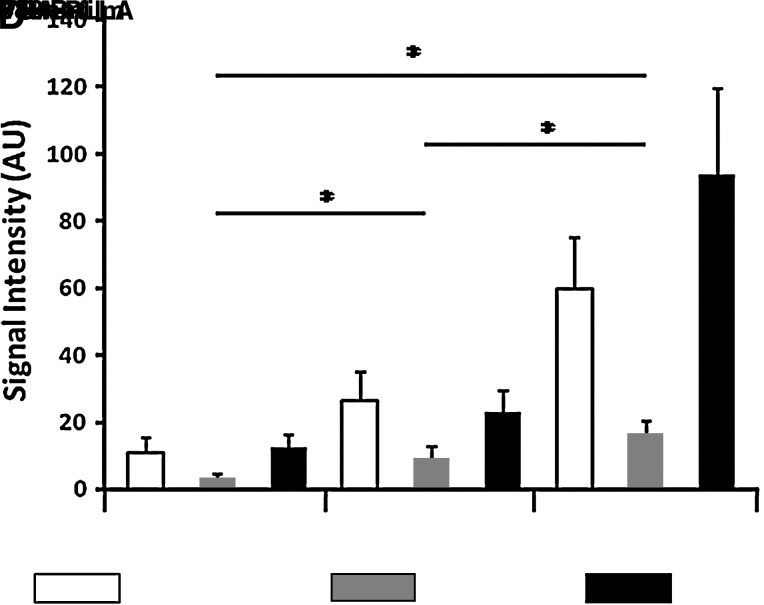

Scaffold

Imaging studies of complex tissues require use of polymers with minimal autofluorescent potential in 488, 633, and 748 nm wavelength channels. We, therefore, first imaged several scaffold candidates (PGA-PLLA; Concordia, Coventry, RI; poly-4-hydroxybutyrate [P4HB] and P4HB-film; Tepha, Lexington, MA) without cell seeding. The gray values in all channels were subsequently quantified and subjected to statistical analysis using analysis of variance to compare differences between groups (p < 0.05). The difference between P4HB and P4HB-film is that the nonwoven mesh is extruded as fibers and then laid into a mesh, and the film is melted into a film. The mesh is very porous and the film is essentially nonporous. In addition, the P4HB-film produces high fluorescence signals in all channels, and therefore could not be used for imaging. In contrast, the PGA-PLLA scaffold showed minimum fluorescence as validated by quantification analysis (Fig. 3) and as such was selected as the candidate for this imaging study. In addition to low autofluorescence, the PGA-PLLA polymers have sufficient tensile strength for implantation into the circulation23 and acceptable biomechanical properties, porosity and biocompatibility, to function as an arterial graft as previously described.9,10,20 We therefore constructed the small-diameter biodegradable tubular scaffolds using 50% PGA, 50% PLLA nonwoven polymers. Nine tubular scaffolds of ∼1 mm in inner diameter, ∼1.3 mm in outer diameter (comparable to carotid artery diameter of mouse model), and 5 mm in length were constructed.

FIG. 3.

Imaging of scaffold materials. (A) PGA-PLLA; (B) P4HB; (C) P4HB-film. (D) Quantitative analysis of signal intensities demonstrates that PGA-PLLA have significantly less fluorescence in all channels (*p < 0.05). Fluorescence channels: blue, 488 nm; green, 633 nm; red, 748 nm. PGA, polyglycolic acid; PLLA, poly-L-lactic acid; P4HB, poly-4-hydroxybutyrate. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Construct development

PGA-PLLA scaffolds were cannulated with a plastic cannula (Angiocath, 20G; Wilburn Medical, Kernesville, NC) and sterilized via ethylene oxide gas. Scaffolds were prewet with 70% ethanol, washed × 3 with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then incubated in a solution of FBS and antibiotics (10 ×) for 2–3 h while cells were prepared. MSC/EPC coculture was initially seeded in a ratio of 3:1 onto the scaffold by directly pipetting cells onto the scaffold, and then changing medium daily. One end of the scaffold was occluded with a sterile surgical clip and pipetting the cell suspension into the lumen through the opposite end. After the initial seeding period, each graft was incubated for 9 days in 80 mL of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) with 20% FBS, 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), 2 ng/mL βFGF, 80 μg/mL of ascorbic acid-2-phosphate, and 1× antibiotic/antimycotic, which was changed every 3–4 days. The angiocatheter was replaced in the lumen on culture day 9 to prevent occlusion due to cellular ingrowth. On culture day 10, the angiocatheter was removed and ∼6 × 106 EPCs were pipetted into the lumen of the graft by applying a surgical clip to one end of the graft, pipetting cells into the lumen, and then applying a clip to the other end of the graft. To allow for endothelial cell adhesion, the graft sat for 10 min before submersion in medium, 24 h before surgical implantation.11,23

Surgical implantation of TEVGs in nude mice

TEVGs were implanted in the right common carotid artery of 12-week-old nude mice under 2% isofluorane anesthesia. A right longitudinal cervicotomy was made; using a dissecting microscope, the right common carotid artery was then separated from the left vagus nerve using fine-tipped dissecting forceps. Two vascular clamps were used to stop the carotid artery flow; a proximal clamp was placed 10 mm from the bifurction of the common carotid artery, and a distal clamp was applied at the bifurcation. After flow was occluded, the right common carotid artery between the two clamps was excised and replaced with the TEVGs, via end-to-end anastomoses created using 10-0 monofilament nylon sutures. The wound was closed with running 7-0 prolene sutures. There were no known complications or mortality during the surgical graft implantation.

Near-infrared imaging agents

Remodeling potential

The activity of matrix-degrading enzymes in the TEVGs was assessed by a near-infrared (NIR) protease-activatable imaging probe (Prosense; ex 680; VisEn) injected intravenously 24 h before imaging (2 nmol/150 μL in PBS). The agent has been validated in a mouse model for tissue remodeling that revealed activity of cysteine proteases (predominantly cathepsin B).15 These quenched substrate probes produce negligible fluorescence at baseline because of closely spaced fluorochromes. However, on protease-mediated cleavage and fluorochrome release, the NIR signal increases by ∼200-fold.

Function

Blood pooling NIR fluorescence imaging probes have been widely used to image the vasculature of different organs in various disease processes,30 serving as a tool for studying coronary circulation and cardiac function.31 In general, these agents circulate in the blood up to 2 h, allowing the imaging of vessels. We used blood pooling NIR agent to assesses the blood flow through surgical anastomoses (Angiosense; ex 750; VisEn) injected at the time of imaging (10 nmol/150 μL in PBS).

Microscopic laser scanning fluorescence imaging

Microscopic fluorescence imaging was performed with a laser scanning fluorescence microscope specifically developed for imaging small experimental animals (IV100; Olympus). We first imaged unimplanted seeded scaffolds to detect initial cellular GFP signal. Then, mice were imaged at time 0 (n = 3), 7 (n = 3), and 35 (n = 3) days after TEVG implantation. Mice were injected via tail vein with Prosense680 (VisEn) 24 h before imaging and with Angiosense750 (VisEn) during imaging. TEVGs were excited at 488, 633, and 748 nm and images collected in three separate channels using dichronic mirror SDM 570 ad SDM 750 and emission filters BA 505–550 for GFP, BA 650–700 for Prosense680, and BA 770 LP for Angiosense750. Images of 512 × 512 pixels with a pixel size of 2.75 × 2.75 μm/pixel were collected with the FluoView300 software program (Olympus) and stored as multilayer, 16-bit tagged image file format (TIFF) files as previously described by our group.15,32 To avoid cross talk between channels, image collection was done serially. Images were processed and analyzed with ImageJ computer software (version 1.41; Bethesda, MD). After in vivo imaging, TEVGs were excised for direct NIR fluorescence microscopy and histopathological analyses. All imaging procedures were approved by the subcommittee on Research Animal Care at Massachusetts General Hospital.

Correlative histological assessment

Morphological characterization

Tissue samples were frozen in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Sakura Finetech, Torrance, CA), and 5 μm serial sections were cut through the TEVGs. All grafts were stained with hematoxylin and eosin for general morphology, Masson trichrome stain for collagen organization, and von Geison for elastin formation.

NIR fluorescence microscopy

We performed direct NIR fluorescence microscopy to validate GFP signal and proteolytic activity, representing the remodeling process. Fresh cryosections through TEVGs were imaged with an upright epifluoresence microscope (Eclipse 80i; Nikon Instruments, Melville, NY) with a cooled CCD camera (Cascade; Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Fluorescence images were then obtained for GFP signal using filter (480 ± 20 nm excitation and 535 ± 25 nm emission) and for Prosense with filter (650 ±22.5 nm excitation and 710 ± 25 nm emission). The exposure time ranged from 200 to 500 ms.

Immunohistochemistry

To validate the cellular phenotype and proteolytic enzyme expression, immunohistochemistry for myofibroblasts (α-smooth muscle actin, 1A4; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), endothelial cells (anti-mouse CD31 and anti-human CD31; Dako), mouse macrophages (mac-3; BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), cathepsin B (goat polyclonal antibodies; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), and gelatinases (polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse MMP-2 and MMP-9; Chemicon International) was used. The avidin–biotin peroxidase method was performed for immunohistochemistry. The reaction was observed with a 3-amino-9-athyl-carbazol substrate (AEC Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO), which yielded red reaction products. Images were captured with a digital camera (Nikon DXM 1200-F; Nikon Instruments).

Results

Characterization of MSCs and retroviral transfection with GFP

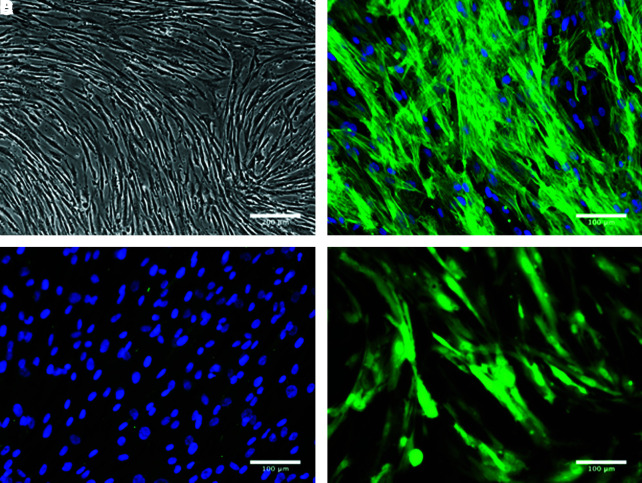

MSCs were isolated from the mononuclear cell fractions of human bone marrow samples as previously described.29 MSCs adhered rapidly to the culture plates, proliferated with ease until confluent, and presented spindle morphology characteristic of mesenchymal cells in culture (Fig. 2A).30 The phenotype of the MSCs was confirmed by indirect immunofluorescent staining: MSCs were shown to express the mesenchymal marker α-smooth muscle actin (Fig. 2B) but not the endothelial marker CD31 (Fig. 2C). The ability of MSCs to differentiate into multiple mesenchymal lineages was also detected in vitro using well-established protocols.30 Differentiation of MSCs into adipocytes, osteocytes, and chondrocytes was confirmed by Oil red O staining (adipogenesis), expression of alkaline phosphatase (osteogenesis), and glycosaminoglycan deposition in pellet cultures (chondrogenesis), respectively (data not shown). Finally, MSCs were retrovirally transfected to ubiquitously express GFP (Fig. 2D) before their use in vivo.

FIG. 2.

MSC characterization preseeding. (A) Phase contrast photomicrograph shows morphology of MSCs; (B) MSC immunostaining with α-SMA; (C) MSC immunostaining with CD31, nuclei stain with 4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI); (D) GFP-labeled MSCs. MSCs, mesenchymal stem cells; α-SMA, alpha-smooth muscle actin; GFP, green fluorescent protein. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

PGA-PLLA is a suitable scaffold

To determine which scaffold would be more appropriate for use in intravital imaging experiments, different scaffold polymer materials (PGA-PLLA, P4HB, and P4HB-film) were imaged and gray values of the fluorescence intensity were analyzed to evaluate their fluorescence properties (Fig. 3). PGA-PLLA showed the least amount of fluorescence in 488 and 633 nm wavelength, the channels used for imaging of GFP-labeled MSCs and remodeling proteins, respectively (Fig. 3A, D). P4HB-based materials showed considerable fluorescence in all three channels (Fig. 3B–D). As such, using PGA-PLLA scaffold material in the construct would provide for the least amount of interfering signal when imaging TEVGs in vivo.

Tissue-engineered constructs show tissue formation before implantation

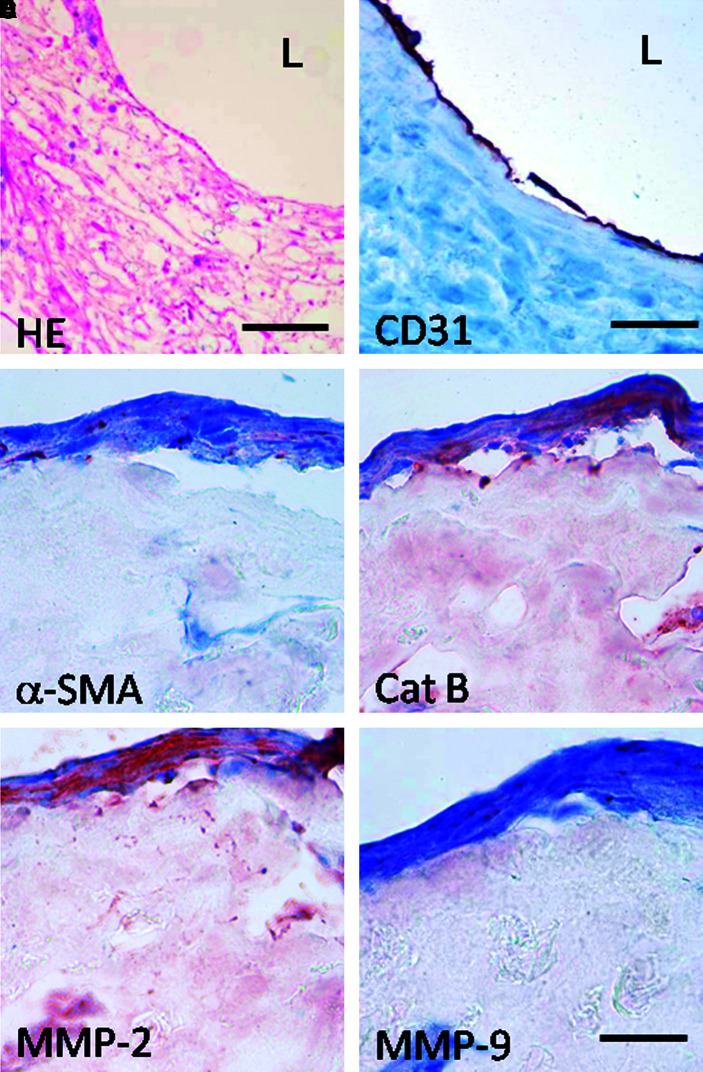

Histological analysis of the cryosections obtained from cell-seeded tissue-engineered constructs before implantation demonstrated organized tissue formation and an endothelial monolayer in the lumen (Fig. 4A, B). The polymers had degraded minimally before implantation. Further immunohistochemical analysis indicated α-smooth muscle actin–positive myofibroblast-like cell phenotype (Fig. 4C) and expression of remodeling enzymes such as cathepsin B, MMP-2, and MMP-9 (Fig. 4D–F).

FIG. 4.

Histological evaluation of preimplanted constructs. (A) HE, bar = 200 μm; (B) CD31, bar = 100 μm; (C) α-SMA; (D) Cathepsin B; (E) MMP-2; (F) MMP-9. Bar = 50 μm; L = lumen. HE, hematoxylin and eosin; MMP, matrix metalloproteinase. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Remodelling of tissue-engineered constructs validated by imaging

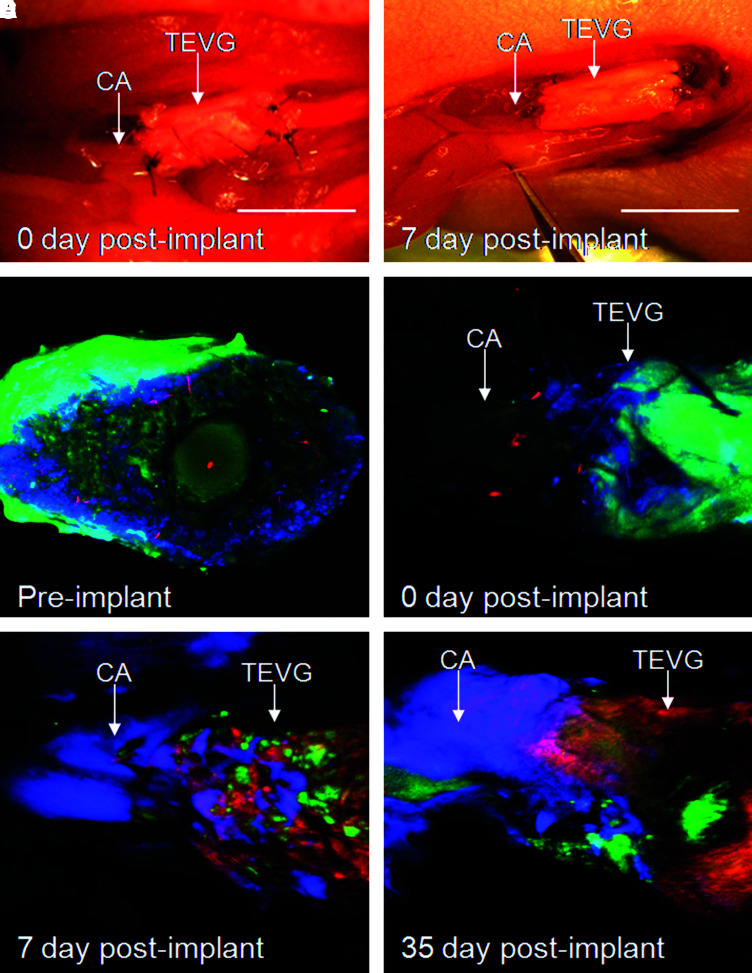

Intravital multichannel laser scanning fluorescence microscopy was used to observe real-time in vivo remodeling activity of TEVGs before implantation, immediately after implantation, and at 7 and 35 days after implantation (Fig. 5; green: GFP, ex 488; red: Prosense680, ex 633; blue: Angiosense750, ex 748). Imaging of the preimplanted TE construct demonstrated GFP-positive cells on the surface and throughout the scaffold, but no proteolytic cathepsin activity (Fig. 5C). Immediately after implantation, grafts showed strong GFP signal (green) on the graft surface, adequate patency of the graft anastomosis detected by Angiosense (blue), and demonstrated a larger diameter of the TE graft than the native artery, consistent with the macroscopic appearance of the graft (Fig. 5D). At day 7, the grafts showed patchy GFP signal (green) and strong protease activity (red) indicating an active remodeling process (Fig. 5E). At 35 days, implants demonstrated predominantly proteolytic activity and less GFP-positive cells, suggesting that the original MSCs were likely replaced by other cells (Fig. 5F). Intravital imaging clearly detected the signal from a blood pooling imaging agent at the anastomoses of 7- and 35-day implants (Fig. 5E, F). Using this imaging approach, we could show that all implanted grafts were patent. However, the limitation of this method is that intravital microscopy cannot penetrate through the thickened wall of the polymer-based tissue-engineered constructs, and for that reason, we cannot assure that all grafts were clear of obstruction.

FIG. 5.

Imaging of TEVGs. (A) Macroscopic pictures of native carotid artery and TEVGs at implantation. (B) Surgical field of implanted TEVGs at 7 day after implantation. (C) Intravital molecular imaging of TEVGs at the time before implantation (cross section). (D–F) Intravital molecular imaging of TEVGs (site of anastomosis) immediately after implantation (D), and 7 days (E) and 35 days (F) postimplantation (green, GFP; red, Prosense680; blue, Angiosense750). CA, mouse carotid artery; TEVGs, tissue-engineered vascular grafts. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

TEVG remodeling validated by histology

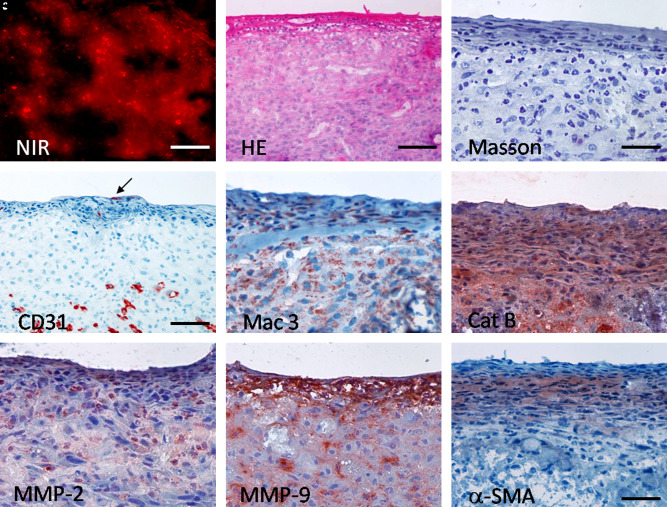

NIR imaging of the tissue-engineered graft 7 days after implantation showed increased remodeling detected by proteolytic enzyme activity (Prosense680; Fig. 6A). Histological analysis revealed layered vascularized tissue and the presence of diffusely distributed macrophages detected by murine mac-3 antibody (Fig. 6B–E). Lumen endothelization was not consistently present (Fig. 6D). Importantly, cathepsin B expression was prominent in the majority of cells, corroborating NIR imaging findings (Fig. 6F). Expression of MMP-2, particularly, MMP-9, was found in fewer cells (Fig. 6G, H).

FIG. 6.

Remodeling of TEVGs 7 days after implantation. (A) NIR fluorescent imaging exhibited proteolytic activity on the sections through TEVGs at 7 day explant; (red, Prosense680); bar = 50 μm. HE and immunohistochemistry correlated with NIR signal. (B) HE, bar = 100 μm; (C) Masson trichrome, bar = 50 μm; (D) CD31 in endothelium (arrow) and microvessels, bar = 100 μm; (E) Mac3; (F) Cathepsin B; (G) MMP-2; (H) MMP-9, (I) α-SMA. Bar (E–I) = 50 μm. NIR, near-infrared. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

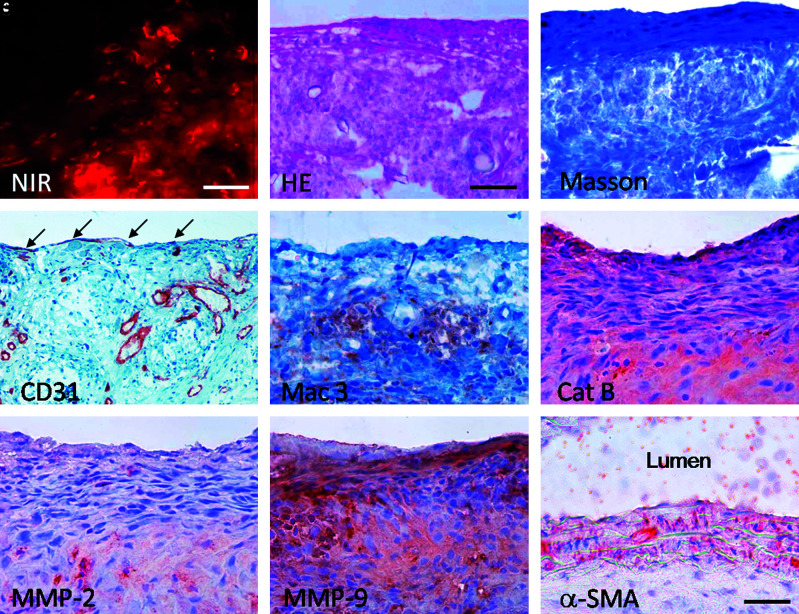

Fluorescence NIR microscopy (Prosense680) registered active remodeling of TEVGs at 35 days (Fig. 7A). TEVGs showed distinct layers of organized cells (Fig. 7B), collagen on the surface (Fig. 7C), and sparse endothelization (Fig. 7D). Elastin was not detected (data not shown). In addition, the macrophages were more sparse and appeared to form clusters (Fig. 7E). Remodeling enzymes, particularly, cathepsin B and MMP-9, were abundantly present at this stage (Fig. 7F–H). Of note, the difference between MMP-2 and MMP-9 expression was more prominent than after 7 days, indicating that MMP-9 is actively involved in late remodeling. The anastomosis lumen showed no indication of thrombus formation (Fig. 7I).

FIG. 7.

Remodeling of TEVGs 35 days after implantation. (A) NIR fluorescent imaging exhibited proteolytic activity on the sectiones through TEVGs at 35 day explant (red, Prosense680); bar = 50 μm. HE and immunohistochemistry correlated with NIR signal. (B) HE, bar = 100 μm; (C) Masson trichrome, bar = 50 μm; (D) CD31 in endothelium (arrow) and microvessels, bar = 100 μm; (E) Mac3; (F) Cathepsin B; (G) MMP-2; (H) MMP-9; (I) α-SMA through anastomosis area. Bar (E–I) = 50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

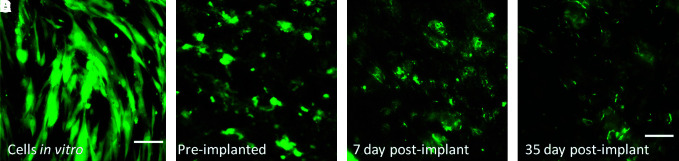

GFP-labeling signal is preserved over time

GFP-labeling signal intensity, although decreased, remained present over time (Fig. 8). The number of cells in the TEVGs was qualitatively fewer at 35 days than 7 days, supporting our in vivo imaging findings.

FIG. 8.

Overtime changes of GFP signal in MSCs. (A) In vitro before seeding; bar = 100 μm; (B) preimplanted, (C) 7 days postimplantation, (D) 35 days postimplantation. Bar (B–D) = 50 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertonline.com/ten.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that intravital molecular imaging can be utilized to observe the dynamic remodeling processeses of a small-caliber TEVG implanted into mouse systemic circulation. Key findings documented here show (1) that in vivo remodeling and maturation of TEVGs could be monitored by NIR protease-activatable imaging agents; (2) GFP labeling of the implanted cells provides a means to track cells over time; and (3) TEVG patency could be monitored simultaneously by introducing fluorescence molecular imaging agents labeling blood pool. (4) In addition, our imaging findings were validated by standard histological methods, and demonstrated that the remodeling process involves and is perhaps initiated by macrophage invasion, and that by day 35, the majority of the initially seeded human MSCs were replaced by host murine cells as detected by immunohistochemistry to mouse-specific antibodies. Over time, the remodeling enzyme activity decreased and grafts displayed layered collagenous tissue.

The tissue engineering paradigm used in our study, in which mononuclear cells derived from bone marrow and seeded on biodegradable polymer scaffolds are used to create a vascular graft, has been previously demonstrated.6,33–35 Moreover, successful postoperative results have been reported in humans.5,36 However, studies of the biological and cellular behavior of human cells are warranted. Therefore, using a nude mouse model for this study had a number of benefits. First, the minimized immune response of nude mice allowed us to study human cells as a source for TEVGs.23,24 In addition, using human cells in preclinical TEVG development has the advantage of identifying biological characteristics of human cells, which could potentially influence their clinical potential.11 Moreover, a human–mouse chimeric system allows for detailed cell-tracking experiments based on species-specific markers, providing further insights into the cellular mechanisms involved in vascular neotissue development. There are significant differences between human and murine vascular systems such as size, morphology, and accelerated neointimal hyperplasia (in mice). However, fundamental similarities between both species could allow the translation of findings from a murine model toward clinical application.22

The mechanism of vascular neotissue formation in TEVG is largely unknown. Hemodynamic forces in the arterial circulation could play an important role in the remodeling process of the graft by contributing to the recruitment and proliferation of MMP-expressing cells.37 As in other studies, we observed a significant macrophage infiltration in the TEVG wall, implicating a role for inflammation in vascular neotissue formation. Macrophages degrade the extracellular matrix by the secretion of proteases such as cathepsins and MMPs and facilitate their migration through the inflamed tissue. Although MMPs are key mediators of vascular remodeling, there is incomplete data on the biological roles of MMP-2 and MMP-9 activity.38 MMP-9 overexpression in vascular smooth muscle cells leads to expansive remodeling and thinning of the intima in rat carotid arteries,39 and in MMP-2 and MMP-9 knockout mice, remodeling and neointima formation are induced by carotid ligation.40,41

Nevertheless, MMPs play a major role in the healing process.41 Moreover, even though macrophage activity can be destructive, this activity seems necessary to promote healing.41 However, it is difficult to distinguish inflammation as part of a remodeling or a healing process from inflammation as part of an elaborate immune response or disease. In our study, the mouse model lacks a functional T-cell–mediated immune system, which circumvents host-versus-graft rejection; however, it may influence results with regard to remodeling. Prior reports using scaffolds from similar polymers have demonstrated no evidence of an adaptive immune response to the biomaterials used in this study.23,42 Nude mice exhibit an intact innate immune system, which means that nude mice are capable of mounting a similar inflammatory response to scaffold material like immunocompetent mice.23 As a result, we conclude that the inflammation demonstrated in this pilot study is a part of remodeling activity inherent to neotissue formation. However, additional studies investigating long-term remodeling and growth of TEVG in a larger number of mice are needed.

In previous studies from our laboratories, we demonstrated promising results in tissue engineering and molecular imaging.15,20,21,32 Here, we offer a sensitive and specific detection of fluorescent signals that allows for multispectral imaging of biological processes in vivo in tissue engineered structures. Specifically, we demonstrated that this imaging approach may serve as an excellent tool to monitor remodeling activity and cell fate in functional TEVGs. Using different NIR fluorescent agents, information about graft maturation, function, and cell fate can be gained from one imaging session. Hence, the model described herein provides benefits for studying neotissue formation of implanted small-diameter TEVGs.

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated the feasibility of evaluating remodeling of TEVGs by means of molecular imaging. A better understanding of the process of neotissue formation is important to the continued development and rationale design of TEVGs. This multidisciplinary experimental approach has the advantage of evaluating remodeling and growth of TEVG in vivo and provides a step toward the development of a reliable noninvasive assessment tools with potential clinical utility.43

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Wijck-Casper-Stam Foundation (J.H.), U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (W81XWH-05-1-0115) (J.B.), and AHA 0835460N (E.A.). The authors would like to thank Yoshiko Iwamoto for excellent histological technique, Dr. Soo-Young Kang for assistance with the retroviral transfection of the cells, and David Martin (Tepha) for providing P4HB-based scaffold samples.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.DeFrances C.J. Lucas C.A. Buie V.C. Golosinskiy A. National Hospital Discharge Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2006;2008(5):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dearani J.A. Danielson G.K. Puga F.J. Schaff H.V. Warnes C.W. Driscoll D.J. Schleck C.D. Ilstrup D.M. Late follow-up of 1095 patients undergoing operation for complex congenital heart disease utilizing pulmonary ventricle to pulmonary artery conduits. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:399–410. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)04547-2. discussion 410–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.L'Heureux N. McAllister T.N. de la Fuente L.M. Tissue-engineered blood vessel for adult arterial revascularization. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1451. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc071536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rabkin E. Schoen F.J. Cardiovascular tissue engineering. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2002;11:305. doi: 10.1016/s1054-8807(02)00130-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin'oka T. Matsumura G. Hibino N. Naito Y. Watanabe M. Konuma T. Sakamoto T. Nagatsu M. Kurosawa H. Midterm clinical result of tissue-engineered vascular autografts seeded with autologous bone marrow cells. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:1330. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roh J.D. Brennan M.P. Lopez-Soler R.I. Fong P.M. Goyal A. Dardik A. Breuer C.K. Construction of an autologous tissue-engineered venous conduit from bone marrow-derived vascular cells: optimization of cell harvest and seeding techniques. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42:198. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaushal S. Amiel G.E. Guleserian K.J. Shapira O.M. Perry T. Sutherland F.W. Rabkin E. Moran A.M. Schoen F.J. Atala A. Soker S. Bischoff J. Mayer J.E., Jr. Functional small-diameter neovessels created using endothelial progenitor cells expanded ex vivo. Nat Med. 2001;7:1035. doi: 10.1038/nm0901-1035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shinoka T. Tissue engineered heart valves: autologous cell seeding on biodegradable polymer scaffold. Artif Organs. 2002;26:402. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1594.2002.07004.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schmidt D. Asmis L.M. Odermatt B. Kelm J. Breymann C. Gossi M. Genoni M. Zund G. Hoerstrup S.P. Engineered living blood vessels: functional endothelia generated from human umbilical cord-derived progenitors. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1465–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.05.066. discussion 1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirensky T.L. Breuer C.K. The development of tissue-engineered grafts for reconstructive cardiothoracic surgical applications. Pediatr Res. 2008;63:559. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000305938.92695.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson G.N. Mirensky T. Brennan M.P. Roh J.D. Yi T. Wang Y. Breuer C.K. Functional small-diameter human tissue-engineered arterial grafts in an immunodeficient mouse model: preliminary findings. Arch Surg. 2008;143:488. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.5.488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin'oka T. Imai Y. Ikada Y. Transplantation of a tissue-engineered pulmonary artery. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:532. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102153440717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jaffer F.A. Libby P. Weissleder R. Molecular imaging of cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2007;116:1052. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.647164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sosnovik D.E. Nahrendorf M. Weissleder R. Magnetic nanoparticles for MR imaging: agents, techniques and cardiovascular applications. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:122. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0710-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aikawa E. Nahrendorf M. Sosnovik D. Lok V.M. Jaffer F.A. Aikawa M. Weissleder R. Multimodality molecular imaging identifies proteolytic and osteogenic activities in early aortic valve disease. Circulation. 2007;115:377. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.654913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deguchi J.O. Aikawa E. Libby P. Vachon J.R. Inada M. Krane S.M. Whittaker P. Aikawa M. Matrix metalloproteinase-13/collagenase-3 deletion promotes collagen accumulation and organization in mouse atherosclerotic plaques. Circulation. 2005;112:2708. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.562041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deguchi J.O. Aikawa M. Tung C.H. Aikawa E. Kim D.E. Ntziachristos V. Weissleder R. Libby P. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: visualizing matrix metalloproteinase action in macrophages in vivo. Circulation. 2006;114:55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.619056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jaffer F.A. Libby P. Weissleder R. Molecular and cellular imaging of atherosclerosis: emerging applications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:1328. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nahrendorf M. Sosnovik D.E. Weissleder R. MR-optical imaging of cardiovascular molecular targets. Basic Res Cardiol. 2008;103:87. doi: 10.1007/s00395-008-0707-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutherland F.W. Perry T.E. Yu Y. Sherwood M.C. Rabkin E. Masuda Y. Garcia G.A. McLellan D.L. Engelmayr G.C., Jr. Sacks M.S. Schoen F.J. Mayer J.E., Jr. From stem cells to viable autologous semilunar heart valve. Circulation. 2005;111:2783. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.498378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sodian R. Hoerstrup S.P. Sperling J.S. Daebritz S. Martin D.P. Moran A.M. Kim B.S. Schoen F.J. Vacanti J.P. Mayer J.E., Jr. Early in vivo experience with tissue-engineered trileaflet heart valves. Circulation. 2000;102(19 Suppl 3):III22. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goyal A. Wang Y. Su H. Dobrucki L.W. Brennan M. Fong P. Dardik A. Tellides G. Sinusas A. Pober J.S. Saltzman W.M. Breuer C.K. Development of a model system for preliminary evaluation of tissue-engineered vascular conduits. J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41:787. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roh J.D. Nelson G.N. Brennan M.P. Mirensky T.L. Yi T. Hazlett T.F. Tellides G. Sinusas A.J. Pober J.S. Saltzman W.M. Kyriakides T.R. Breuer C.K. Small-diameter biodegradable scaffolds for functional vascular tissue engineering in the mouse model. Biomaterials. 2008;29:1454. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.11.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lopez-Soler R.I. Brennan M.P. Goyal A. Wang Y. Fong P. Tellides G. Sinusas A. Dardik A. Breuer C. Development of a mouse model for evaluation of small diameter vascular grafts. J Surg Res. 2007;139:1. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2006.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson G.N. Roh J.D. Mirensky T.L. Wang Y. Yi T. Tellides G. Pober J.S. Shkarin P. Shapiro E.M. Saltzman W.M. Papademetris X. Fahmy T.M. Breuer CK. Initial evaluation of the use of USPIO cell labeling and noninvasive MR monitoring of human tissue-engineered vascular grafts in vivo. FASEB J. 2008;22:3888. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-107367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Melero-Martin J.M. De Obaldia M.E. Kang S.Y. Khan Z.A. Yuan L. Oettgen P. Bischoff J. Engineering robust and functional vascular networks in vivo with human adult and cord blood-derived progenitor cells. Circ Res. 2008;103:194. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.178590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pittenger M.F. Mackay A.M. Beck S.C. Jaiswal R.K. Douglas R. Mosca J.D. Moorman M.A. Simonetti D.W. Craig S. Marshak D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kitamura T. Onishi M. Kinoshita S. Shibuya A. Miyajima A. Nolan G.P. Efficient screening of retroviral cDNA expression libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.20.9146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melero-Martin J.M. Khan Z.A. Picard A. Wu X. Paruchuri S. Bischoff J. In vivo vasculogenic potential of human blood-derived endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2007;109:4761. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-062471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alencar H. Mahmood U. Kawano Y. Hirata T. Weissleder R. Novel multiwavelength microscopic scanner for mouse imaging. Neoplasia. 2005;7:977. doi: 10.1593/neo.05376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hattori H. Higuchi K. Nogami Y. Amano Y. Ishihara M. Takase B. A novel real-time fluorescent optical imaging system in mouse heart: a powerful tool for studying coronary circulation and cardiac function. Circulation. 2009;2:277. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.108.806596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aikawa E. Nahrendorf M. Figueiredom J.L. Swirski F.K. Shtatland T. Kohler R.H. Jaffer F.A. Aikawa M. Weissleder R. Osteogenesis associates with inflammation in early-stage atherosclerosis evaluated by molecular imaging in vivo. Circulation. 2007;116:2841. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.732867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cho S.W. Kim I.K. Kang J.M. Song K.W. Kim H.S. Park C.H. Yoo K.J. Kim B.S. Evidence for in vivo growth potential and vascular remodeling of tissue-engineered artery. Tissue Eng. 2009;15:901. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumura G. Hibino N. Ikada Y. Kurosawa H. Shin'oka T. Successful application of tissue engineered vascular autografts: clinical experience. Biomaterials. 2003;24:2303. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Matsumura G. Ishihara Y. Miyagawa-Tomita S. Ikada Y. Matsuda S. Kurosawa H. Shin'oka T. Evaluation of tissue-engineered vascular autografts. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:3075. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shin'oka T. [Clinical results of tissue-engineered vascular autografts seeded with autologous bone marrow cells] Nippon Geka Gakkai Zasshi. 2004;105:459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim Y.S. Galis Z.S. Rachev A. Han H.C. Vito R.P. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 are associated with high stresses predicted using a nonlinear heterogeneous model of arteries. J Biomech Eng. 2009;131:011009. doi: 10.1115/1.3005163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J. Nie L. Razavian M. Ahmed M. Dobrucki L.W. Asadi A. Edwards D.S. Azure M. Sinusas A.J. Sadeghi M.M. Molecular imaging of activated matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling. Circulation. 2008;118:1953. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.789743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mason D.P. Kenagy R.D. Hasenstab D. Bowen-Pope D.F. Seifert R.A. Coats S. Hawkins S.M. Clowes A.W. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 overexpression enhances vascular smooth muscle cell migration and alters remodeling in the injured rat carotid artery. Circ Res. 1999;85:1179. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.12.1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Johnson C. Galis Z.S. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 differentially regulate smooth muscle cell migration and cell-mediated collagen organization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:54. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000100402.69997.C3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galis Z.S. Khatri J.J. Matrix metalloproteinases in vascular remodeling and atherogenesis: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Circ Res. 2002;90:251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Athanasiou K.A. Niederauer G.G. Agrawal C.M. Sterilization, toxicity, biocompatibility and clinical applications of polylactic acid/polyglycolic acid copolymers. Biomaterials. 1996;17:93. doi: 10.1016/0142-9612(96)85754-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hjortnaes J. Bouten C.V. Van Herwerden L.A. Grundeman P.F. Kluin J. Translating autologous heart valve tissue engineering from bench to bed. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2009;15:307. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEB.2008.0565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]