Summary

The putative confession (PC) instruction (i.e., “[suspect] told me everything that happened and wants you to tell the truth”) during forensic interviews with children has been shown to increase the accuracy of children's statements, but it is unclear whether adults' perceptions are sensitive to this salutary effect. The present study examined how adults perceive children's true and false responses to the PC instruction. Participants (n = 299) watched videotaped interviews of children and rated the child's credibility and the truthfulness of his/her statements. When viewing children's responses to the PC instruction, true and false statements were rated as equally credible, and there was a decrease in accuracy for identifying false denials as lies. These findings suggest that participants viewed the PC instruction as truth-inducing. Implications for the forensic use of the PC instruction are discussed.

Keywords: child credibility, deception detection, interviewing children, putative confession

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Children's involvement in criminal proceedings increased after the spike in reports of abuse and neglect during the 1990s (OPRE, 2009; Petersen, Joseph, & Feit, 2013). The resulting deluge of child credibility research supports the notion that, with unbiased interview strategies, children can provide valuable information to a criminal investigation (e.g., Brown & Lamb, 2015; Quas, Goodman, Ghetti, & Redlich, 2000). Children are questioned in legal contexts when they witness violence or are victims of alleged maltreatment from an adult. These forensic interviews aim to elicit accurate disclosures from the children. That is, the purpose of a forensic interview is to obtain a disclosure—but only when maltreatment truly occurred. Two problems interfere with this goal. The first problem is that children can be misled because they are susceptible to suggestion (Bruck & Ceci, 1999), and adults can pressure children to falsely report maltreatment that conforms to their preconceived agenda (Bruck & Ceci, 2004). Conversely, abused children may fail to disclose their abuse. Research with child abuse victims and adult survey respondents has shown that children often feel complicit in their abuse or anticipate that they will be viewed as complicit by others, deterring them from disclosing (Hershkowitz, Lanes, & Lamb, 2007; Martin, Anderson, Romans, Mullen, & O'Shea, 1993). Hence, the challenge for forensic interviewers is to support children enough to overcome reluctance to disclose but not so far as to produce false reports (Lyon, 2014).

2 ∣. THE PUTATIVE CONFESSION INSTRUCTION

A series of studies have examined 4- to 9-year-old children's disclosure patterns when they felt jointly implicated in a transgression with an adult stranger. The stranger encouraged them to play with a series of toys, but then two of the toys were designed to break in the children's hands. The stranger admonished secrecy, warning that they might “get in trouble” if someone found out that they broke the toys. Most children failed to disclose the transgression in response to recall questions, whereas recognition questions increased disclosure but elicited some false yes responses and many false no responses (Ahern, Stolzenberg, McWilliams, & Lyon, 2016; Lyon et al., 2014; McWilliams, Stolzenberg, Williams, & Lyon, n.d.; Quas, Stolzenberg, & Lyon, 2018; Rush, Stolzenberg, Quas, & Lyon, 2017). However, several studies have found that use of the putative confession (PC), in which the interviewer tells the child that the stranger disclosed “everything that happened and wants you to tell the truth,” increased transgression disclosures in response to recall questions and did so equally across 4- to 9-year-olds (McWilliams et al., n.d.; Lyon et al., 2014; Quas et al., 2018; Rush et al., 2017). Similar effects were found using a hypothetical form of the PC, in which the interviewer added “what if I told you” to the instruction (Stolzenberg, McWilliams, & Lyon, 2017).

Because the interviewer does not specify what “everything” or “the truth” entails, the instruction conveys different meanings to children who have and have not experienced a transgression. Only a child who has experienced a transgression is likely to interpret “everything that happened” as referring to a transgression. Furthermore, in failing to provide specific details about the suspect's statements, the instruction avoids the suggestive effects of telling children about other witnesses' reports (Garven, Wood, Malpass, & Shaw, 1998) or asking children to speculate or pretend (Schreiber, Wentura, & Bilsky, 2001). Indeed, the PC has not been found to increase false reports when a transgression did not occur (Lyon et al., 2014; Quas et al., 2018), even among children suggestively questioned (Cleveland, Quas, & Lyon, 2018; Rush et al., 2017). Additionally, the PC has been effective among children who are less responsive to a request that they promise to tell the truth, including younger and maltreated children (McWilliams et al., n.d.). Hence, interviewers wishing to avoid the potentially leading effect of recognition questions might find the PC valuable in eliciting disclosures from reluctant children.

3 ∣. ASSESSING CHILDREN'S CREDIBILITY AND DETECTING DECEPTION

An important issue is how children who maintain secrecy in the face of the putative confession are perceived. It is essential to understand not just what increases (or decreases) children's honesty, but what affects adult perceptions of their honesty. Adults are responsible for assessing the credibility of children's statements, deciding whether to move forward with an investigation, and once an investigation is complete, deciding whether wrongdoing has occurred.

The PC might affect adult's perceptions of children's credibility and their ability to distinguish between truth-tellers and liars, and its effect would vary depending on whether adults view the PC as increasing honesty or as suggestive. If adults view the PC as eliciting honest disclosures from children, then they would be more likely to believe children who fail to disclose, and this could impair their ability to detect false denials. If adults view the PC as suggestive, then they would be less likely to believe children who disclose, and this could impair their ability to detect true reports.

There is surprisingly little research examining adults' credibility judgments or deception detection abilities regarding children who receive different types of interview instructions. There is limited research suggesting that adults will judge children as more credible and make more accurate judgments if children are asked competency questions and promise to tell the truth. One study has shown that adults find a child more credible and accurate if the judge conducted a preliminary competency inquiry and questioned the child about school, family, and awareness of the difference between a truth and lie (Connolly, Gagnon, & Lavoie, 2008). However, deception detection accuracy could not be assessed in this study because ground truth was unknown. If adults view the PC as inducing honesty, then it might have similar effects. Another study found that adults were better at detecting deception when 3- to 11-year-old children had engaged in moral discussions about lie telling or had promised to tell the truth before being questioned (Leach, Talwar, Lee, Bala, & Lindsay, 2004). However, the participants were not shown the preliminary discussions. In real-world interviews, observers would both see the instructions and see how the children responded.

On the other hand, research on lay understanding of suggestibility raises the possibility that adults will view the PC as suggestive. The research finds that lay people's understanding is at best uneven; adults have some understanding that children are suggestible but have poor understanding of differences among different interview strategies (McAuliff & Kovera, 2007; Quas, Thompson, & Clarke-Stewart, 2005).

As a general matter, adults are mediocre lie detectors who tend to classify true and false statements at a rate significantly above chance but that, practically speaking, has little consequence (54–57% accuracy; Aamodt & Custer, 2006; Bond & DePaulo, 2006; Gongola, Scurich, & Quas, 2017). Many potential moderators of deception detection accuracy have revealed small or mixed effects (for a review, see Gongola et al., 2017 and Bond & DePaulo, 2006).

One robust effect in the deception detection literature is the truth bias, which is the tendency to believe that people—both adults and children—are honest. There are at least two explanations for this effect. First, if the majority of interpersonal communication is honest, or at least expected to be honest, then the tendency to judge others' statements as truthful is a useful heuristic (Street & Richardson, 2015; Swann, 1984). A second explanation is that the bias is a by-product of cognitive processing. Gilbert (1991) proposed that, in the same way one immediately trusts that the object she sees is a chair, one tends to believe an idea she understands is the truth. Disconfirming a proposition that sounds plausible requires additional time, effort, and evidence. How adults perceive the effects of the PC could affect their proclivity to evince a truth bias.

4 ∣. THE PRESENT STUDY

The purpose of the present study is to further extend this research by determining how adults perceive children's true and false statements in response to the PC compared with a control instruction (i.e., “Tell me everything that happened.”). Two research questions will be investigated. First, how do adults perceive children's credibility when questioned with the PC? Second, does the PC instruction have any effect on adult's deception detection accuracy? In other words, will participants be more likely to believe a false statement, specifically a false denial, or will they be more likely to identify a false denial as a lie?

On the basis of the research finding that adults view competency questions as inducing honesty in children, we hypothesized that adults would view the PC as increasing the likelihood that children would be honest. This would increase their accuracy when assessing true responses and decrease their accuracy when assessing false responses. However, given adults' uneven ability to recognize suggestive questioning as such, an alternative hypothesis is that adults would perceive the PC as suggestive and thus view children's disclosures as less credible.

5 ∣. METHOD

5.1 ∣. Participants

The sample was composed of 302 participants (50.5% female) recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online platform where surveys and questionnaires are posted for volunteers to complete in exchange for monetary compensation. Their ages ranged from 18 to 74 (median = 35, mean = 37.7, SD = 12.78), 38.5% were married, 46.5% were parents, and 52.5% identified as politically liberal, 22.4% moderate, and 25% conservative. Additionally, 7.4% (n = 22) participants reported that they were employed in a position in which they had regular contact with children; the majority were school teachers and five worked in various health services. Two participants were discarded from the sample for failing an attention check question (Oppenheimer, Meyvis, & Davidenko, 2009). One other participant was dropped answering “no” to a check question that asked if they were able to view the interview video, resulting in a total sample of 299 participants.

5.2 ∣. Preparation of stimulus materials

The videotaped interviews were created by Stolzenberg and colleagues (for a detailed study description, see Stolzenberg et al., 2017). The procedure used the broken toy paradigm described in the introduction. For the present study, we edited the videos to include the recall and recognition questions asked by the interviewer following rapport building. The interviewer started with either no instruction (control group) or the hypothetical PC. In the control group, the interviewer asked the child to tell her “everything that happened” when the stranger came in while she was away. In the PC condition the interviewer said “What if I said that [the suspect] told me everything that happened, and he wants you to tell the truth” before asking the child to tell her what happened. The children's initial responses ranged from one short sentence (e.g., “We played with toys”) to about 30 seconds of speaking; the response length and number details were evenly dispersed across the conditions in the study design. The interviewer asked the child to list all the toys that he/she played with, then followed up with cued recall questions about each toy (e.g., “You said you played with the dog, what happened next?”). The children provided between one and three sentences about how each of the six different toys worked (e.g., “the dog did a flip”). After the free and cued recall questions, the interviewer asked recognition questions about each toy (e.g., “Did the dog break?”). Some of the children disclosed toy breakage in response to the recognition questions to which the interviewer repeated the child's disclosure and asked the child to tell her everything that happened.

5.3 ∣. Design and procedure

The design was a 3 × 2 (type of disclosure: false denial, true denial, true report; instruction type: putative confession, control instruction) fully crossed, between-subjects factorial. We did not include false reports because these were quite rare in the original study and tended to be unelaborated yes responses rather than descriptions of breakage. Each condition contained two videos, one of each gender and similar ages, to balance out any potential idiosyncrasies associated with any particular child. We only utilized videotaped interviews in which the child's parents gave explicit consent that their video could be viewed. The study procedure was approved by the Institutional Review Board.

Each participant watched one of 12 videotaped interviews (average duration 3 min and 30 s), all of which were conducted with Hispanic children (six girls and six boys), ranging between 6 and 9 years old. The children's ages and interview duration were equally distributed across the conditions. Each taped interview presented a close-up of the child over the interviewer's shoulder and a picture-in-picture view of both the child and interviewer.

Participants were instructed to watch the interview with a child describing a play session, during which some toys may or may not have been broken, and that they would be asked to determine whether any toys broke based on the child's answers.

After watching the interview, participants rated whether they thought each of the six toys had broken on Likert scales from 1 (the toy definitely did not break) to 6 (the toy definitely broke). Respondents also rated their impression of the child's credibility on 14 items (e.g., credible, believable, and accurate) as well as five items regarding the perceived quality of the child's responses (e.g., detailed, strong, and long) on a 1 to 7 semantic differential scale. Half of the items were reverse coded. We conducted an exploratory factor analysis on the credibility scale by entering the 14 items into a principal component analysis with varimax rotation, which extracted two factors. Table 1 shows a complete list of the items and their factor loadings. Factor 1, labeled “credibility”, included 12 of the items and accounted for 49% of the variance (eigenvalue = 6.85). Factor 2 included three items and accounted for 7.9% of the variance (eigenvalue = 1.10). Only Factor 1 was used in the following analyses, and those 12 items were collapsed into a composite score (α = 0.91). At the end of the survey, the respondents provided basic demographic information. Participants were thanked for their participation and compensated. On average, participants took 8 min 13 s (SD = 4 min) to complete the survey.

TABLE 1.

Factor loadings of the credibility scale

| Items | Factor 1 (credibility) | Factor 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Reliable: unreliable | 0.81 | |

| Credible: deceptive | 0.70 | |

| Believable: unconvincing | 0.82 | |

| Likable: disagreeable | 0.56 | |

| Coherent: incoherent | 0.68 | |

| Competent: incompetent | 0.82 | |

| Typical: atypical | 0.46 | |

| Genuine: fake | 0.58 | |

| Suggestible: steadfast | 0.58 | |

| Accurate: inaccurate | 0.81 | |

| Honest: deceitful | 0.80 | |

| Consistent: inconsistent | 0.50 | 0.57 |

| Confident: unsurea | 0.69 | |

| Calm: nervousa | 0.76 |

Note. Loadings less than 0.4 were omitted.

Indicates items that were dropped from the analyses.

6 ∣. RESULTS

6.1 ∣. Perceptions of child credibility

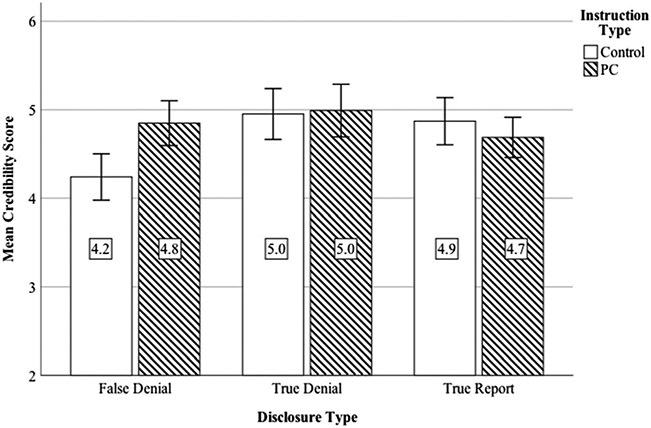

Perceived credibility scores were entered as the dependent measure into a 3 × 2 (disclosure type: false denial, true denial, true report; instruction type: PC, control) analysis of variance. There was a significant main effect for disclosure type, F(2, 298) = 5.149, p = 0.006, h2p = 0.034, which was qualified by a significant interaction between disclosure and instruction type, F(2, 298) = 4.803, p = 0.009, h2p = .032. The main effect for instruction type was not significant (p = 0.16). Figure 1 shows that false denials under the control instruction were rated as less credible compared with all of the other groups. Participants perceived false denials under the PC instruction as equally credible as true reports and true denials across instruction type. In other words, participants were more suspicious of dishonest children only in the control instruction. This pattern supports the hypothesis that participants viewed the PC instruction as truth-inducing. Participants rated the false denials as equally credible as the true statements when they were questioned with the PC instruction, and there were no significant differences in perceptions of children's true reports between the PC and control instruction conditions.

FIGURE 1.

Perceived credibility of children's true and false statements as a function interview instruction. Note that the error bars represent 95% confidence intervals

6.2 ∣. Deception detection accuracy

Participants indicated whether they thought each toy had broken. Their accuracy was calculated based on whether the child was telling the truth (i.e., if the toys broke or not). The child did break a toy in the true report and false denial conditions, and if the participant indicated that they thought at least one of the six toys broke, then they would be accurate (=1), and those who believed that none of the toys had broken were inaccurate (=0). Similarly, the children in the true denial condition had played with six toys, and none of them broke. Thus, participants were accurate if they indicated that no toys had broken (=1) and inaccurate if they believed that a toy had broken (=0). Orthogonal contrast codes for the instruction type and disclosure type variables were constructed using the strategy presented in Wendorf (2004).

Participant accuracy was entered as the dependent variable into a binary logistic regression with the disclosure type, interview type, and the interaction between them as the predictor variables. The model was significant, x2(5, 299) = 81.6, p < 0.001. Table 2 shows the percentage of correct judgments for each condition. A significant main effect emerged for disclosure type (Wald(2) = 29.947, p < 0.001). Compared with false denials, participants were 4.9 times more likely to be accurate when judging true denials, 95% CI [2.1, 11.4], Wald(1) = 13.716, p < 0.001, and 38.7 times more likely for true reports, 95% CI [8.5, 175.3], Wald(1) = 22.486, p < 0.001. Deception detection accuracy significantly differed as a function of the instruction type, Wald(1) = 6.215, p = 0.013. Compared with the PC instruction, participants were 2.8 times (95% CI [1.2, 6.2]) more likely to be accurate in the control instruction condition. The disclosure by instruction type interaction was not significant (p = 0.89). However, follow-up analyses showed that participants were significantly more likely to be accurate judging false denials in the control condition compared with the PC condition (χ2[1, n = 104] = 6.36, p = 0.021), but not for true denials or true reports (χ2[1, n = 95] = 1.78, p = 0.18; χ2[1, n = 100] = 0.43, p = 0.51, respectively). Indeed, accuracy rate for false denials were significantly below 50% in the PC condition (95% CI [28%, 47%]) and significantly above 50% in the no instruction control condition (95% CI [51%, 73%]).

TABLE 2.

Mean (SD) percent correct as a function of instruction type and disclosure type

| Disclosure type |

Instruction type | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC | Control | Total** | |

| True report | 95.8% (20.2) | 98.1% (13.9) | 97.0% (17.2) |

| True denial | 74.5% (44.1) | 85.4% (35.7) | 80.0% (40.2) |

| False denial | 37.3% (48.8) | 62.2% (49.0) | 48.1% (50.2) |

| Total* | 66.9% (42.2) | 82.8% (37.9) | |

p = 0.013.

p = 0.001.

These results also reveals the presence of a truth bias. Participants rated statements as truthful (75.9%) more often than they were (66.6%), t(298) = 3.17, p = 0.002.

7 ∣. DISCUSSION

The analyses revealed several noteworthy findings concerning perceptions of children's credibility and participant's deception detection accuracy as a function of the type of disclosure (i.e., child's true or false statements) and the type of interview instruction employed (i.e., hypothetical PC or control instruction). First, the results support the hypothesis that adults perceived the PC as increasing honesty. In the control instruction condition, participants correctly rated the false denials as less credible than the true denials. However, in the PC condition, participants rated the false denials as credibly as the true denials. Moreover, there was a corresponding drop in deception detection accuracy among adults in the PC condition. Deception detection accuracy was significantly below 50% when judging false denials in the PC instruction condition and significantly above 50% in the control instruction condition.

Second, the results do not support the alternative possibility that adults perceived the PC instruction as suggestive. The PC did not influence credibility ratings for children's true reports of breakage. That is, adults did not rate children's true reports as less credible when they were evoked by the PC, which one would expect if they believed that the PC would induce children to false alarm. Third, there was evidence of a truth bias, a common finding in the deception detection literature (Bond & DePaulo, 2006; Gongola et al., 2017). Participants were more likely to classify the children as truthful and were better at identifying true statements as honest than at identifying false statements as lies.

Fourth, participants' accuracy when judging true statements was extremely high and near perfect when judging true disclosures of breakage. These rates were higher than the averages reported in a recent meta-analysis by Gongola et al. (2017). However, the meta-analysis identified a significant amount of between-study variability, which indicates that there are important moderators of deception detection still to uncover. One possibility is that elaborately staged events lead to more believable true reports. Several other child deception detection studies have found similarly high rates of accuracy for true reports (e.g., Ball & O'Callaghan, 2001; Orcutt, Goodman, Tobey, Batterman-Faunce, & Thomas, 2001; Shao, 2007; Strömwall & Granhag, 2005). Similar to the present study, the children in Orcutt et al. (2001) played several games with a confederate. In other studies, the children participated in a magic demonstration (Strömwall & Granhag, 2005), an art lesson (Shao, 2007), and a dentist visit (Ball & O'Callaghan, 2001). Another possibility is that eliciting more elaborated reports from children leads to more believable true reports. In the present study, interviewers exhausted children's recall and followed up children's yes responses with a request for elaboration, and this resulted in longer interviews that produced more information for participants to assess. Finally, the transgressive nature of the event may have made children's true disclosures more believable. Future research is needed to test these possible moderators of credibility and deception detection accuracy and to determine what additional information would make participants more suspicious of children's true reports.

Future research is also necessary to identify the reasons participants in the PC condition were less adept at credibility judgments and deception detection. On the one hand, participants viewing false denials were more likely to believe children in the PC condition than in the control condition, consistent with an enhanced truth bias. However, participants viewing true denials and true reports were no more likely to believe children when the PC had been administered. Although this could be attributable to a ceiling effect in the case of the true reports, because true reports in the control condition were endorsed as true by 98% of subjects, it does not explain participant's responses to the true denials. If anything, participants viewing the true denials were nonsignificantly less accurate in the PC condition (75%) than in the control condition (85%), but if the PC merely increased truth bias, participants in the PC condition should have been more accurate.

Complicating the picture is the fact that in the study from which the videos were drawn, the PC had a positive effect on children's reports, such that children who experienced toy breakage were significantly more likely to reveal that breakage (Stolzenberg et al., 2017). Hence, children who disclosed in response to the PC were selected out, and children in the PC false denial group resisted the truth-inducing effects of the PC; they may have been more motivated to conceal breakage or more able to do so, or both. If they were better at concealing breakage, then this provides an alternative explanation for why deception detection was lower in the PC false denial group than in the control false denial group. It is also possible that the PC had more subtle effects on children's behavior, both verbal and non-verbal, short of affecting their disclosure. This could have affected children in all groups. As a result, it is unclear whether the participants' poorer discrimination ability when viewing the children administered the PC is attributable to the participants' attitudes about the PC or the PC's effects on children, or both.

Future work is needed to disentangle these possible effects. In order to assess the effects of the truth bias, participants could be shown two videos and asked which child was honest (or dishonest), thus ensuring participants identified equal numbers of children as deceptive or honest. Furthermore, participants could be directly asked about their perceptions of the PC's effect and their reasons for classifying children as honest or dishonest, though participants may not be fully aware of the reasons for their judgments. Finally, showing participants multiple videos would make it possible to develop a clearer picture of the factors that influence participants' judgments.

Another limitation of the present study is that there were no children who falsely reported toy breakage during the interview. As noted above, this is because the PC did not have a suggestive effect in the study from which the videos were drawn, and only a very small number of children provided elaborated false reports. A complete picture of deception detection accuracy would have been obtained if both false denials and false reports could have been included. For example, the extent to which the high accuracy rate for true reports could be attributable to a truth bias is unclear. This is a common problem in deception detection research; the meta-analysis by Gongola et al. (2017) identified only four studies out of 45 that had all four types of statements (i.e., true reports, false reports, true denials, and false denials).

The adult participants were recruited from Amazon Mechanical Turk, and online samples have raised concerns about participant motivation and attentiveness to the stimulus materials (Goodman, Cryder, & Cheema, 2013). In the present study, a page-timer was activated while participants watched the interview video that restricted access to the next page during the length of the video. As is standard practice with online surveys, there was also an attention check question embedded in the study to identify and remove inattentive participants (Oppenheimer et al., 2009). Additionally, although online samples tend to oversample younger, more liberal, and more computer-literate individuals, nevertheless, they do tend to be more representative of the adult population in the United States than undergraduate samples (Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011).

The findings may have implications for use of the PC in practice. The advantage of the PC is that it elicits true disclosures from children who would otherwise not disclose and does not appear to increase false disclosures (McWilliams et al., n.d.; Lyon et al., 2014; Quas et al., 2018; Rush et al., 2017; Stolzenberg et al., 2017). This study suggests that lay observers recognize that the PC increases true disclosures without increasing false disclosures. However, interviewers will hesitate to use the PC because of ethical reasons; if the suspect has not in fact confessed, then the instruction is untrue. One option is to include in suspect interviews a question whether the suspect has revealed “everything” and “wants the child to tell the truth” (Lyon et al., 2014). Another option is to use the hypothetical form of the PC (the form used in this study), in which the interviewer adds “what if I said” that “[the suspect] told me everything that happened” (Stolzenberg et al., 2017). However, in these cases the instruction is still problematic; it is not literally false, but nevertheless misleading. The issue for interviewers is how to balance the risks and benefits of alternative approaches.

This study provides an additional caution: the PC may lead observers to exaggerate the likelihood that a child who fails to disclose a transgression is being honest. Previous research has found that, compared with the other types of statements, adults tend to have the most difficulty judging the veracity of false denials (Block et al., 2012). An important question for future research is whether trained professionals who conduct forensic interviews with children or who evaluate forensic interviews are subject to the same biases. Clearly, much more work needs to be done to identify means of increasing children's willingness to disclose wrongdoing.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

NICHD, Grant/Award Number: HD087685

REFERENCES

- Aamodt MG, & Custer H (2006). Who can best catch a liar? A meta-analysis of individual differences in detecting deception. The Forensic Examiner, 15, 6–11. [Google Scholar]

- Ahern EC, Stolzenberg SN, McWilliams K, & Lyon TD (2016). The effects of secret instructions and yes/no questions on maltreated and non-maltreated children's reports of a minor transgression. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 34, 784–802. 10.1002/bsl.2277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball CT, & O'callaghan J (2001). Judging the accuracy of children's recall: A statement-level analysis. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 7, 331–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Block SD, Shestowsky D, Segovia DA, Goodman GS, Schaaf JM, & Alexander KW (2012). “That never happened”: Adults' discernment of children's true and false memory reports. Law and Human Behavior, 36, 365–374. 10.1037/h0093920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond CF Jr., & DePaulo BM (2006). Accuracy of deception judgments. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 10, 214–234. 10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown DA, & Lamb ME (2015). Can children be useful witnesses? It depends how they are questioned. Child Development Perspectives, 9, 250–255. 10.1111/cdep.12142 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruck M, & Ceci S (2004). Forensic developmental psychology: Unveiling four common misconceptions. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 13, 229–232. 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00314.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruck M, & Ceci SJ (1999). The suggestibility of children's memory. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 419–439. 10.1146/annurev.psych.50.1.419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, & Gosling SD (2011). Amazon's Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5. 10.1177/1745691610393980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland KC, Quas JA, & Lyon TD (2018). The effects of implicit encouragement and the putative confession on children's memory reports. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly DA, Gagnon NC, & Lavoie JA (2008). The effect of a judicial declaration of competence on the perceived credibility of children and defendants. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 13, 257–277. 10.1348/135532507X206867 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garven S, Wood JM, Malpass RS, & Shaw JS III (1998). More than suggestion: The effect of interviewing techniques from the McMartin Preschool case. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83, 347–359. 10.1037/0021-9010.83.3.347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert DT (1991). How mental systems believe. American Psychologist, 46, 107–119. 10.1037/0003-066X.46.2.107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gongola J, Scurich N, & Quas JA (2017). Detecting deception in children: A meta-analysis. Law and Human Behavior, 41, 44–54. 10.1037/lhb0000211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman JK, Cryder CE, & Cheema A (2013). Data collection in a flat world: The strengths and weaknesses of Mechanical Turk samples. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26, 213–224. 10.1002/bdm.1753 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkowitz I, Lanes O, & Lamb ME (2007). Exploring the disclosure of child sexual abuse with alleged victims and their parents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31, 111–123. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.09.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leach AM, Talwar V, Lee K, Bala N, & Lindsay RCL (2004). “Intuitive” lie detection of children's deception by law enforcement officials and university students. Law and Human Behavior, 28, 661–685. 10.1007/s10979-004-0793-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon TD (2014). Interviewing children. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 10, 73–89. 10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110413-030913 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon TD, Wandrey L, Ahern E, Licht R, Sim MP, & Quas JA (2014). Eliciting maltreated and nonmaltreated children's transgression disclosures: Narrative practice rapport building and a putative confession. Child Development, 85, 1756–1769. 10.1111/cdev.12223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin J, Anderson J, Romans S, Mullen P, & O'Shea M (1993). Asking about child sexual abuse: Methodological implications of a two stage survey. Child Abuse & Neglect, 17, 383–392. 10.1016/0145-2134(93)90061-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAuliff BD, & Kovera MB (2007). Estimating the effects of misleading information on witness accuracy: Can experts tell jurors something they don't already know? Applied Cognitive Psychology, 21, 849–870. 10.1002/acp.1301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams K, Stolzenberg SN, Williams S, & Lyon TD (n.d.). Increasing maltreated and nonmaltreated disclosure of a minor transgression: The effects of back-channel utterances, a promise to tell the truth, and an incremental putative confession. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Office of Planning Research and Evaluation (OPRE). (2009). National incidence study of child abuse and neglect (NIS-4), 2004–2009. Retrieved from: http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/research/project/national-incidence-study-of-child-abuse-and-neglect-nis-4-2004-2009

- Oppenheimer DM, Meyvis T, & Davidenko N (2009). Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 867–872. 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Orcutt HK, Goodman GS, Tobey AE, Batterman-Faunce JM, & Thomas S (2001). Detecting deception in children's testimony: Fact-finders' abilities to reach the truth in open court and closed-circuit trials. Law and Human Behavior, 25, 339–372. 10.1023/A:1010603618330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen A, Joseph J, & Feit M (2013). New directions in child abuse and neglect research. Report of the Committee on Child Maltreatment Research, Policy, and Practice for the Next Decade: Phase II.

- Quas JA, Goodman GS, Ghetti S, & Redlich AD (2000). Questioning the child witness: What can we conclude from the research thus far? Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 1, 223–249. 10.1177/1524838000001003002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quas JA, Stolzenberg SN, & Lyon TD (2018). The effects of promising to tell the truth, the putative confession, and recall and recognition questions on maltreated and non-maltreated children's disclosure of a minor transgression. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 166, 266–279. 10.1016/j.jecp.2017.08.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quas JA, Thompson WC, & Clarke-Stewart KA (2005). Do jurors “know” what isn't so about child witnesses? Law and Human Behavior, 29, 425–465. 10.1007/s10979-005-5523-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush EB, Stolzenberg SN, Quas JA, & Lyon TD (2017). The effects of the putative confession and parent suggestion on children's disclosure of a minor transgression. Legal and Criminological Psychology, 22, 60–73. 10.1111/lcrp.12086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber N, Wentura D, & Bilsky W (2001). "What else could he have done?" Creating false answers in child witnesses by inviting speculation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 525–532. 10.1037/0021-9010.86.3.525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y (2007). Credibility Assessment of Misinformed vs. Deceptive Children (unpublished Master's thesis). Cornell University, Ithaca, NY. [Google Scholar]

- Stolzenberg SN, McWilliams K, & Lyon TD (2017). The effects of the hypothetical putative confession and negatively valenced yes/no questions on maltreated and nonmaltreated children's disclosure of a minor transgression. Child Maltreatment, 22, 167–173. 10.1177/1077559516673734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Street CN, & Richardson DC (2015). Lies, damn lies, and expectations: How base rates inform lie–truth judgments. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29, 149–155. 10.1002/acp.3085 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strömwall LA, & Granhag PA (2005). Children's repeated lies and truths: Effects on adults' judgments and reality monitoring scores. Psychiatry, Psychology and Law, 12, 345–356. 10.1375/pplt.12.2.345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Swann WB Jr. (1984). Quest for accuracy in person perception: A matter of pragmatics. Psychological Review, 91, 457–477. 10.1037/0033-295X.91.4.457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendorf CA (2004). Primer on multiple regression coding: Common forms and the additional case of repeated contrasts. Understanding Statistics, 3, 47–57. 10.1207/s15328031us0301_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]