Abstract

Neuroblastoma is a pediatric tumor of the sympathetic nervous system. Its clinical course ranges from spontaneous tumor regression to fatal progression. To investigate the molecular features of the divergent tumor subtypes, we performed genome sequencing on 416 pretreatment neuroblastomas and assessed telomere maintenance mechanisms in 208 of these tumors. We found that patients whose tumors lacked telomere maintenance mechanisms had an excellent prognosis, whereas the prognosis of patients whose tumors harbored telomere maintenance mechanisms was substantially worse. Survival rates were lowest for neuroblastoma patients whose tumors harbored telomere maintenance mechanisms in combination with RAS and/or p53 pathway mutations. Spontaneous tumor regression occurred both in the presence and absence of these mutations in patients with telomere maintenance-negative tumors. On the basis of these data, we propose a mechanistic classification of neuroblastoma that may benefit the clinical management of patients.

Neuroblastoma is a pediatric tumor of the sympathetic nervous system with substantially varying clinical courses (1). Roughly half of neuroblastoma patients have a dismal outcome despite intensive multimodal treatment, whereas other patients have an excellent outcome because their tumors either spontaneously regress or differentiate into benign ganglioneuromas. Patients are considered to be at high risk of death if they are diagnosed with metastatic disease when they are older than 18 months or when their tumor exhibits genomic amplification of the proto-oncogene MYCN (2). All other patients are classified as intermediate or low risk (referred to as non–high-risk patients in this study) and receive limited or no cytotoxic treatment. In addition to MYCN amplification, rearrangements of the TERT locus (encoding the catalytic subunit of telomerase) or inactivating mutations in ATRX (encoding a chromatin remodeling protein) have been found predominantly in high-risk tumors (3–7). Whereas both MYCN and TERT alterations lead to telomere maintenance by induction of telomerase, ATRX loss-of-function mutations have been associated with activation of the alternative lengthening of telomeres (ALT) pathway (5, 8). Neuroblastomas also harbor recurrent mutations in ALK (encoding a receptor tyrosine kinase) (9, 10). To date, these genomic data have not produced a coherent model of pathogenesis that can explain the extremely divergent clinical phenotypes of neuroblastoma.

In the study, we aimed to evaluate whether the divergent clinical phenotypes in neuroblastoma are defined by specific genetic alterations. To this end, we examined 218 pretreatment tumors and matched normal control tissue (i.e., blood) by whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing (WES and WGS, respectively) from patients covering the entire spectrum of the disease (fig. S1 and tables S1 to S3). In line with previous studies, we found 14.9 somatic singlenucleotide variations (SNVs) per tumor exome on average (median, 12 SNVs per tumor exome; fig. S2) (4, 6). Because mutations in genes of the RAS and p53 pathways have been detected in relapsed neuroblastoma (11–13), we hypothesized that such alterations may not only be relevant at the time of relapse but may also determine the clinical course of neuroblastoma at diagnosis. We thus defined a panel of 17 genes related to the RAS pathway (11 genes including ALK) or the p53 pathway (6 genes) based on our own and published data (fig. S3 and tables S4 to S7) and examined their mutation frequency in pretreatment tumors (Fig. 1A). Focal amplifications, homozygous deletions, and variants of amino acids recorded in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (14) were considered. We found alterations of these genes in 46 of 218 cases of the combined WES and WGS cohort. In an independent cohort of 198 pretreatment tumors examined by targeted sequencing (fig. S1 and tables S1 and S2), we detected alterations of these genes in 28 of 198 cases, resulting in an overall mutation frequency of 17.8% in the combined cohorts (74 of 416 cases; fig. S4 and tables S8 and S9). RAS and p53 pathway mutations were enriched in overall clonal cancer cell populations (95% versus 71% clonal events, P = 0.021; fig. S5), indicating their evolutionary selection during tumor development.

Fig. 1. Mutations of RAS and p53 pathway genes in pretreatment neuroblastomas are associated with poor survival of patients.

(A) Schematic representation of the RAS and p53 pathways highlighting genes mutated in pretreatment neuroblastoma of the combined WES and WGS and targeted sequencing cohort (n = 416). The fraction of tumors affected by SNVs or by somatic copy number alterations (SCNAs) is indicated in the gene boxes as percentages and by color code. RAS represents the genes NRAS, HRAS, and KRAS. (B to D) Diseasespecific survival of all patients (B), high-risk patients (C), and non–high-risk patients (D) of the same cohort (n = 416) according to the absence (blue) or presence (red) of RAS or p53 pathway gene mutations (5-year disease-specific survival ± SE: 0.807 ± 0.023 versus 0.498 ± 0.061, 0.657 ± 0.037 versus 0.341 ± 0.071, and 0.993 ± 0.007 versus 0.822 ± 0.081, respectively).

Mutations in RAS and p53 pathway genes occurred in both high- and non–high-risk tumors, although at lower frequencies in the latter group (21.3% versus 13.3%, P = 0.048, fig. S6). Overall, the presence of such alterations was strongly associated with poor patient outcome (Fig. 1B and fig. S7). We did not observe significant differences between the prognostic effects of RAS and p53 pathway alterations; however, patients whose tumors had ALK mutations had better event-free survival than those whose tumors harbored other RAS pathway mutations (fig. S8). In high-risk patients, alterations of RAS or p53 pathway genes were also associated with poor outcome (Fig. 1C and fig. S9, A and B), both in MYCNamplified and non–MYCN-amplified cases (fig. S9C). Such alterations also identified patients with unfavorable clinical courses in the non–high-risk cohort (Fig. 1D and fig. S9D). The presence of these mutations predicted dismal outcome in multivariable analyses independently of prognostic markers currently used for neuroblastoma risk stratification (15) in the entire cohort and in both high-risk and non–high-risk patients (fig. S10). Together, our findings point to a crucial role of RAS and p53 pathway genes in the development of unfavorable neuroblastoma, which is in line with increased frequencies of such mutations at clinical relapse (11–13) and with data from genetically engineered mouse models showing that RAS pathway activation augments neuroblastoma aggressiveness (16–18).

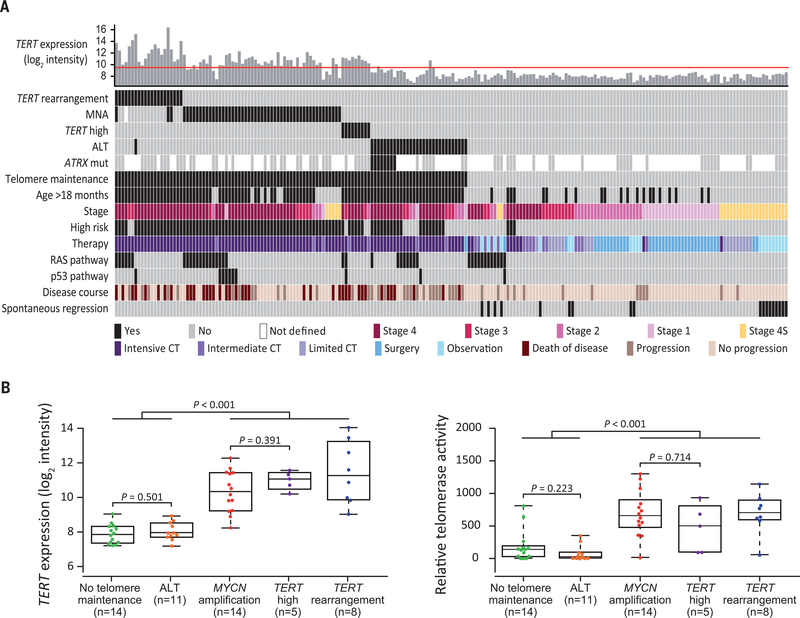

Despite the overall association of RAS and p53 pathway mutations with poor outcome, however, we noticed that the clinical courses of non–high-risk patients bearing such mutations varied greatly, ranging from spontaneous regression to fatal tumor progression (fig. S11). On the basis of previous work (5, 19–21), we hypothesized that these differences may be related to the presence or absence of telomere maintenance mechanisms. We therefore examined the genomic status of the MYCN and TERT loci, as well as ALT-associated promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies (APBs) and TERT expression in a cohort of 208 of 416 tumors (fig. S1). We observed MYCN amplification in 52 cases, TERT rearrangements in 21 cases, and APBs in 31 cases (Fig. 2A and table S10). In line with previous observations (5, 22), TERT expression was elevated in tumors bearing TERT rearrangements or MYCN amplification, indicating telomerase activation (fig. S12, A and B). In APB-positive tumors, TERT expression was low and telomere length ratios high, thus supporting an ALT phenotype (fig. S12, A, C, and D). We also assessed the genomic status of ATRX in 83 evaluable tumors and found mutations that were likely to be inactivating in eight of these, all of which were ALT positive (Fig. 2A and table S10); by contrast, mutations of DAXX, which encodes another protein participating in chromatin remodeling at telomeres, were not detected. We observed neither significant alterations in ATRX or DAXX gene methylation status or gene expression patterns in ALT-positive tumors (fig. S13) nor significant associations between ALT and p53 pathway mutations (3 of 31 ALT-positive cases mutated, 7 of 177 ALT-negative cases mutated; P = 0.173) (23). Immunohistochemical staining revealed loss of nuclear ATRX expression in one tumor bearing an ATRX nonsense mutation, whereas expression was retained in tumors with ATRX in-frame deletions (fig. S14) (23). Furthermore, we noticed that a small fraction of neuroblastomas lacking MYCN or TERT alterations had elevated TERT mRNA levels (fig. S12A). We therefore determined and validated a TERT expression threshold to identify wildtype MYCN and TERT (MYCNWT and TERTWT) tumors whose TERT mRNA levels are comparable to those of tumors bearing genomic MYCN or TERT alterations, pointing toward telomerase activation (fig. S15). In fact, high TERT mRNA levels corresponded to elevated enzymatic telomerase activity in these tumors, as well as in tumors harboring MYCN amplification or TERT rearrangements (Fig. 2B). On the basis of these and our previous observations (5), we considered tumors telomere maintenance positive if they harbored TERT rearrangements or MYCN amplification, elevated TERT expression in the absence of these alterations, or were positive for APBs as a marker of ALT (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Telomere maintenance mechanisms in pretreatment neuroblastomas.

(A) Distribution of telomere maintenance mechanisms, RAS and p53 pathway gene mutations, and clinical covariates in 208 pretreatment neuroblastomas (ordered from left to right). The red line in the top panel indicates the TERT expression threshold as described in fig. S15. CT, chemotherapy; MNA, MYCN amplification. (B) TERT mRNA expression (left) and corresponding enzymatic telomerase activity (right) in 52 neuroblastoma samples. Boxes represent the first and third quartiles; whiskers represent minimum and maximum values; TERT high represents tumors lacking genomic MYCN or TERT alterations with TERT expression above threshold.

In the set of non–high-risk tumors bearing RAS or p53 pathway mutations (23 of 208 cases), we found evidence for telomerase or ALT activation in nine cases (fig. S16A). The outcome of these patients was poor, whereas all patients whose tumors lacked telomere maintenance mechanisms have survived to date, with no or limited cytotoxic therapy (fig. S16B). Importantly, this finding was validated in an additional series of 20 pretreatment non–high-risk neuroblastomas with RAS pathway gene mutations that had not been part of the initial WES and WGS or targeted sequencing cohorts (figs. S1 and S16, C and D, and table S11). Together, telomere maintenance mechanisms thus clearly discriminated the divergent clinical phenotypes occurring in non–high-risk tumors bearing RAS or p53 pathway mutations (Fig. 3, A and B).

Fig. 3. Telomere maintenance mechanisms discriminate favorable and adverse clinical course in non–high-risk neuroblastoma bearing RAS or p53 pathway mutations.

(A) Telomere maintenance status and clinical covariates in the combined discovery and validation cohort of non-high-risk patients whose tumors harbored RAS or p53 pathway mutations (n = 43). Patients are ordered from left to the right. The red line in the top panel indicates the TERT expression threshold. NBL, neuroblastoma ID; w/o, without. (B) Event-free (top) and disease-specific (bottom) survival of the same patients according to the absence (blue) or presence (red) of telomere maintenance mechanisms (n = 41; 5-year event-free survival ± SE, 0.847 ± 0.071 versus 0.071 ± 0.069; 5-year disease-specific survival ± SE, 1.0 versus 0.556 ± 0.136). (C) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of a patient whose tumor harbored an ALKR1275Q mutation in the absence of telomere maintenance activity at diagnosis and upon partial tumor regression. (D) Iodine-123 metaiodobenzylguanidine scintigraphy scans of a stage 4 patient with an ALKF1174L mutated, telomere maintenance–negative neuroblastoma at diagnosis and upon complete regression of osteomedullary metastases. LDR, posterior projection (left–dorsal–right); RVL, anterior projection (right–ventral–left). (E) MRI scans of a patient with ALKF1245Y (F1245Y, Phe1245→Tyr) mutated, telomere maintenance–negative thoracic neuroblastoma at diagnosis and after partial regression. Tumor lesions are highlighted by arrows or arrowheads.

The prognostic dependence of RAS pathway mutations on telomere maintenance in non–high-risk disease was highlighted in a patient subgroup that was genetically defined by the presence of ALKR1275Q (R1275Q, Arg1275→Gln) mutations (n = 11 patients): Outcome was excellent only if telomere maintenance mechanisms were absent, and spontaneous regression had been documented in four of these children (Fig. 3C and fig. S16E). Similarly, complete regression of osteomedullary metastases without any chemotherapy had been noticed in a stage 4 patient whose tumor carried the particularly aggressive ALKF1174L (F1174L, Phe1174→Leu) mutation (Fig. 3D) (16). In two other patients with ALK-mutant tumors (NBL8 and NBL-V16), spontaneous differentiation into ganglioneuroblastoma had been found after partial regression in patient NBL8 (Fig. 3E and fig. S16F). Finally, long-term event-free survival without chemotherapy was also recorded in patient NBL59, whose tumor harbored both HRAS and TP53 mutations in the absence of telomere maintenance, whereas patients whose tumors harbored HRAS, NRAS, or TP53 mutations had fatal outcome when telomerase or ALT was activated (Fig. 3A).

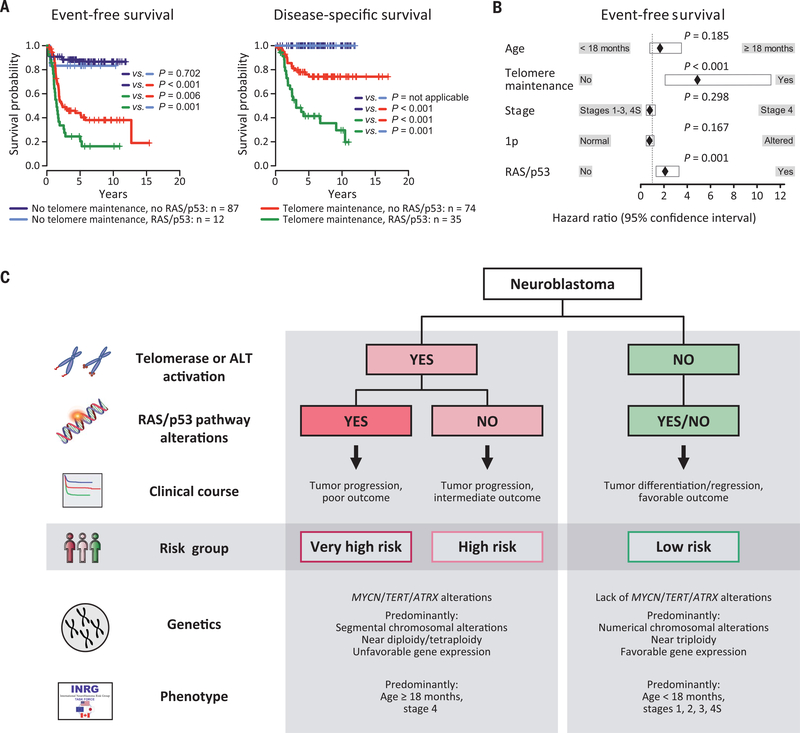

We hypothesized that a general pathogenetic hierarchy of telomere maintenance and RAS or p53 pathway mutations might mechanistically define the different clinical subgroups of neuroblastoma. Indeed, we observed that the outcome of patients whose tumors lacked telomere maintenance (n = 99) was excellent, irrespective of the presence of RAS or p53 pathway mutations (Fig. 4A). Fifty-seven of these patients had never received cytotoxic treatment, including 18 cases with documented spontaneous regression (Fig. 2A and table S10). Our data indicate that RAS or p53 pathway mutations are not sufficient for full malignant transformation and continuous growth of human neuroblastoma in the absence of telomere maintenance. Consistent with this observation, telomerase has been shown to be essential for full malignant transformation of human cells bearing oncogenic HRAS in experimental systems (24), whereas cellular senescence occurs in response to oncogenic HRAS in the absence of telomerase (25). Neuroblastomas lacking telomere maintenance were mainly derived from young patients (mean age at diagnosis, 378 days; fig. S17A) classified as clinical low or intermediate risk(96 of 99 cases; P < 0.001); the remaining three tumors had been obtained from young stage 4 patients (age at diagnosis, 732 to 1035 days) who all have survived event-free to date. By contrast, children whose tumors harbored telomerase or ALT activation were mainly clinical high-risk patients (92 of 109 cases; P < 0.001). Seventeen patients had been clinically classified as low or intermediate risk; however, their clinical course was as unfavorable as that of high-risk patients (fig. S17B), thus supporting the notion that telomere maintenance is a major determinant of neuroblastoma outcome. We also found no significant difference in the outcome of patients whose tumors displayed MYCN amplification compared with those whose tumors had other telomere maintenance mechanisms (fig. S18A). In addition, we observed that the outcome of patients whose tumors exhibited telomere maintenance was devastating when additional RAS or p53 pathway mutations were present, whereas survival was considerably better in their absence (Fig. 4A). Among the former patients, those whose tumors harbored ALK mutations tended to have a more favorable outcome than those whose tumors carried other RAS pathway mutations (fig. S18B). We also observed that the telomere maintenance status did not change over the disease course in 19 of 20 paired neuroblastoma samples biopsied at diagnosis and relapse or progression; in one case, de novo MYCN amplification accompanied by TERT up-regulation occurred at the time of relapse (table S12). This finding suggests that the telomere maintenance status is mostly fixed at diagnosis, which is in line with the notion that low-risk neuroblastoma rarely develops into high-risk disease (26, 27). The clinical relevance of telomere maintenance and RAS or p53 pathway alterations was substantiated by multivariable analysis, in which both alterations independently predicted unfavorable outcome (Fig. 4B). Additional backward selection of variables in this model identified only telomere maintenance and RAS or p53 pathway mutations as independent prognostic markers (telomere maintenance: hazard ratio, 5.184, confidence interval, 2.723 to 9.871, P < 0.001; RAS and/or p53 pathway mutation: hazard ratio, 2.056, confidence interval, 1.325 to 3.190, P = 0.001), whereas the established markers (stage, age, and chromosome 1p status) were not considered in the final model.

Fig. 4. Clinical neuroblastoma subgroups are defined by telomere maintenance and RAS and p53 pathways alterations.

(A) Event-free (left) and disease-specific (right) survival of patients according to the absence or presence of RAS or p53 pathway gene mutations and telomere maintenance activity (n = 208; 5-year event-free survival ± SE, 0.867 ± 0.038 versus 0.833 ± 0.108 versus 0.440 ± 0.061 versus 0.245 ± 0.075; 5-year disease-specific survival ± SE, 1.0 versus 1.0 versus 0.742 ± 0.055 versus 0.414 ± 0.088). Statistical results of pairwise group comparisons are indicated. (B) Multivariable Cox regression analysis for event-free survival (n = 201), considering the prognostic variables age at diagnosis, stage, chromosome 1p status, RAS or p53 pathway mutation, and telomere maintenance activation. MYCN status was not considered separately, as telomere maintenance–positive cases comprised all MYCN-amplified cases by definition. Multivariable analysis for disease-specific survival could not be calculated, because no deadly event occurred in patients whose tumors lacked telomere maintenance, and thus, no hazard ratio can be calculated for this variable. (C) Schematic representation of the proposed mechanistic definition of clinical neuroblastoma subgroups. The classification is built on the presence or absence of telomere maintenance mechanisms and RAS or p53 pathway mutations. In addition, associations with other genetic features [MYCN, TERT, and ATRX alterations; segmental copy number alterations (35); tumor cell ploidy (1, 2); gene expression–based classification (36)] and clinical characteristics (age at diagnosis, stage of disease) are indicated.

Together, our findings demonstrate that the divergent clinical phenotypes of human neuroblastoma are driven by molecular alterations affecting telomere maintenance and RAS or p53 pathways, suggesting a mechanistic classification of this malignancy (Fig. 4C): High-risk neuroblastoma is defined by telomere maintenance caused by induction of telomerase or the ALT pathway. Additional mutations in genes of the RAS or p53 pathway increase tumor aggressiveness, resulting in a high likelihood of death from disease. By contrast, low-risk tumors invariably lack telomere maintenance mechanisms. Because telomere maintenance is essential for cancer cells to achieve immortal proliferation capacity (8, 28), its absence is likely a prerequisite for spontaneous regression and differentiation in neuroblastoma. Our data also indicate that mutations of RAS or p53 pathway genes in tumors without telomere maintenance do not affect patient outcome.

Our findings may have important implications for the diagnosis and treatment of neuroblastoma patients, which should be validated in future prospective clinical trials. Assessment of telomere maintenance mechanisms and a limited set of RAS and p53 pathway genes may be sufficient to accurately estimate patient risk at diagnosis and to guide treatment stratification. In a clinical setting, telomerase activation may be readily determined by examining the genomic status of MYCN and TERT in the majority of cases and supplemented by analysis of TERT expression levels in MYCNWT and TERTWT tumors. It is important to note, though, that classification of patients based on a TERT expression threshold may bear a certain risk of misclassification because of potential confounding factors, such as tumor cell content or RNA integrity of the sample. In addition to analysis of telomerase activation, ALT can be assessed by detection of APBs or, potentially, by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of extrachromosomal circles of telomeric DNA (29). We propose that patients whose tumors lack telomere maintenance may require limited or no cytotoxic treatment, as suggested by the high prevalence of spontaneous regression in these cases, whereas patients whose tumors harbor such mechanisms need intensive therapy. Patients whose tumors carry both telomere maintenance and RAS or p53 pathway alterations, however, are at high risk of treatment failure and death (Fig. 4A). Nonetheless, the fact that these alterations can act in concert provides a rationale for developing novel combination therapies. Compounds interfering with aberrant RAS pathway signaling have shown promising antitumor effects in preclinical models of neuroblastoma (12, 16, 30, 31), and ALK inhibitors have entered clinical trials (32). In addition, therapeutic strategies directed against telomerase or the ALT pathway are the subject of current investigations (28, 33, 34). A combination of therapies targeting these two critical oncogenic pathways in neuroblastoma may thus merit investigation.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the patients and their parents for making available the tumor specimens that were analyzed in this study, and we thank the German neuroblastoma biobank for providing these samples. The Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved collection and use of all specimens in this study. We thank our colleagues N. Hemstedt, H. Düren, and E. Hess for technical assistance and C. Reinhardt for critical reading of the manuscript. We also thank the CMMC light microscope facility for helping us obtain high-quality images of fluorescence in situ hybridization analyses.

Funding: This work was supported by the German Cancer Aid (grant no. 110122 to M.F., F.W., A.S., and J.H.S.; grant no. 70-443, 70-2290-BE I, T12/97/Be1 and 70107712 to F.B.; the Mildred-Scheel professorship to M.P.), the German Ministry of Science and Education (BMBF) as part of the e:Med initiative (grant no. 01ZX1303 and 01ZX1603 to M.P., U.L., R.B., R.K.T., J.H.S., and M.F.; grant no. 01ZX1406 to M.P.; grant no. 01ZX1307 and 01ZX1607 to A.E., F.W., A.S., J.H.S., and M.F.), and the MYC-NET (grant no. 0316076A to F.W.), the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) as part of the SFB 876 (subproject C1, S.R. and A.S.) and as part of the KFO 286 (M.P.), the Berlin Institute of Health (Terminate-NB, A.E. and J.H.S.), the European Union (grant no. 259348 to F.W.), and as part of the OPTIMIZE-NB and ONTHETRRAC consortia (A.E.), the Fördergesellschaft Kinderkrebs-Neuroblastom-Forschung e.V. (M.F.), the German Cancer Research Center (DKFZ) intramural program for interaction projects and the DKFZ–Heidelberg Center for Personalized Oncology (HIPO) and National Center for Tumor Diseases (NCT) Precision Oncology Program (F.W.), the St. Baldricks Foundation (R.J.O.), the German Cancer Consortium (DKTK) Joint Funding program, and the Center for Molecular Medicine Cologne (CMMC).

Footnotes

Competing interests: J.V. is a cofounder of Biogazelle, a company developing RNA-based assays to assess health and treat disease. J.V. is also a cofounder of pxlence, a company providing PCR assays for targeted amplification and sequencing of the human exome. R.K.T. has received consulting fees from NEO New Oncology, a company developing technologies for molecular pathology and clinical research. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All high-throughput sequencing data have been deposited at the European Genome-phenome Archive (www.ebi.ac.uk/ega/) under accession number EGAS00001003244. Microarray data can be accessed from the GEO database (www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) with accession numbers GSE120572 and GSE120650.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Maris JM, Hogarty MD, Bagatell R, Cohn SL, Lancet 369, 2106–2120 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cohn SL et al. , J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 289–297 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung NK et al. , JAMA 307, 1062–1071 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molenaar JJ et al. , Nature 483, 589–593 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peifer M et al. , Nature 526, 700–704 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pugh TJ et al. , Nat. Genet. 45, 279–284 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valentijn LJ et al. , Nat. Genet. 47, 1411–1414 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA, Cell 144, 646–674 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bresler SC et al. , Cancer Cell 26, 682–694 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mossé YP et al. , Nature 455, 930–935 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr-Wilkinson J et al. , Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 1108–1118 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eleveld TF et al. , Nat. Genet. 47, 864–871 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schramm A et al. , Nat. Genet. 47, 872–877 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forbeset al SA., Nucleic Acids Res. 43, D805–D811 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simon T, Spitz R, Faldum A, Hero B, Berthold F, J. Pediatr. Hematol. Oncol. 26, 791–796 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heukamp LC et al. , Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 141ra91 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weiss WA, Aldape K, Mohapatra G, Feuerstein BG, Bishop JM, EMBO J. 16, 2985–2995 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berry T et al. , Cancer Cell 22, 117–130 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi LM et al. , Med. Pediatr. Oncol. 35, 647–650 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hiyama E et al. , Nat. Med. 1, 249–255 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Poremba C et al. , J. Clin. Oncol. 18, 2582–2592 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mac SM, D’Cunha CA, Farnham PJ, Mol. Carcinog. 29, 76–86 (2000). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu XY et al. , Acta Neuropathol. 124, 615–625 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hahn WC et al. , Nature 400, 464–468 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patel PL, Suram A, Mirani N, Bischof O, Herbig U, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, E5024–E5033 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schilling FH et al. , N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 1047–1053 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woods WG et al. , N. Engl. J. Med. 346, 1041–1046 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harley CB, Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 167–179 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Henson JD et al. , Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 1181–1185 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hartet al LS., Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 1785–1796 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Infarinato NR et al. , Cancer Discov. 6, 96–107 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mossé YP et al. , Lancet Oncol. 14, 472–480 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Flynn RL et al. , Science 347, 273–277 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mender I, Gryaznov S, Dikmen ZG, Wright WE, Shay JW, Cancer Discov. 5, 82–95 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Janoueix-Lerosey I et al. , J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 1026–1033 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oberthuer A et al. , Clin. Cancer Res. 21, 1904–1915 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.