Abstract

Background:

Survivors of childhood cancer may be at risk of experiencing pain; a systematic review would advance our understanding of pain in this population.

Purpose:

To describe: (i) the prevalence of pain in survivors of childhood cancer; (ii) methods of pain measurement; (iii) associations between pain and biopsychosocial factors; iv) recommendations for future research.

Data Sources:

Articles published from January 1990 to August 2019 identified in PubMed, PsycINFO, EMBASE, and Web of Science.

Study Selection:

Eligible studies included: 1) original research; 2) quantitative assessments of pain; 3) published in English; 4) a diagnosis of cancer between 0–21 years; 5) survivors at 5 years from diagnosis and/or 2 years from therapy completion; 6) sample size >20.

Data Extraction:

Seventy-three articles were included in the final review. Risk of bias was considered using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. Quality of evidence was evaluated according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation criteria.

Data Synthesis:

Common measures of pain were items created by the authors for the purpose of the study (45.2%) or health-related quality of life/ health status questionnaires (42.5%). Pain was present in 4.3–75% of survivors across studies. Three studies investigated chronic pain according the definition by the International Classification of Diseases.

Conclusions:

Survivors of childhood cancer are at higher risk of experiencing pain compared to controls. Fatigue was consistently associated with pain. Females report more pain than males. Other factors related to pain require stronger evidence. Theoretically grounded, multidimensional measurements of pain are absent from the literature.

Keywords: neoplasms, pediatrics, pain, survivorship, psycho-oncology

Precis:

Survivors of childhood cancer are at higher risk of experiencing pain compared to controls. Future research is urgently needed to discern the true prevalence of pain among this vulnerable population and to develop interventions to enhance the quality of survivorship.

Introduction

Currently, there are over 500,000 survivors of pediatric cancer in North America alone.1 Given increasing survival rates for this population, it is imperative that we maximize long-term quality of life outcomes. There is emerging research documenting significant pain, including chronic pain (i.e., pain lasting > 3 months)2 among survivors of pediatric cancer. Pain (e.g., musculoskeletal pain, headaches, generalized pain) has been noted to significantly impact quality of life,3 and psychosocial well-being. Survivors of pediatric cancer may have a unique relationship to pain, given the prominence of pain across multiple points of the cancer journey. In addition, given that pain in the general population has been linked to many negative health consequences, including poorer sleep and mental health, it is critical that pain be examined among survivors of childhood cancer as their risks for late effects may be compounded by the experience of pain.

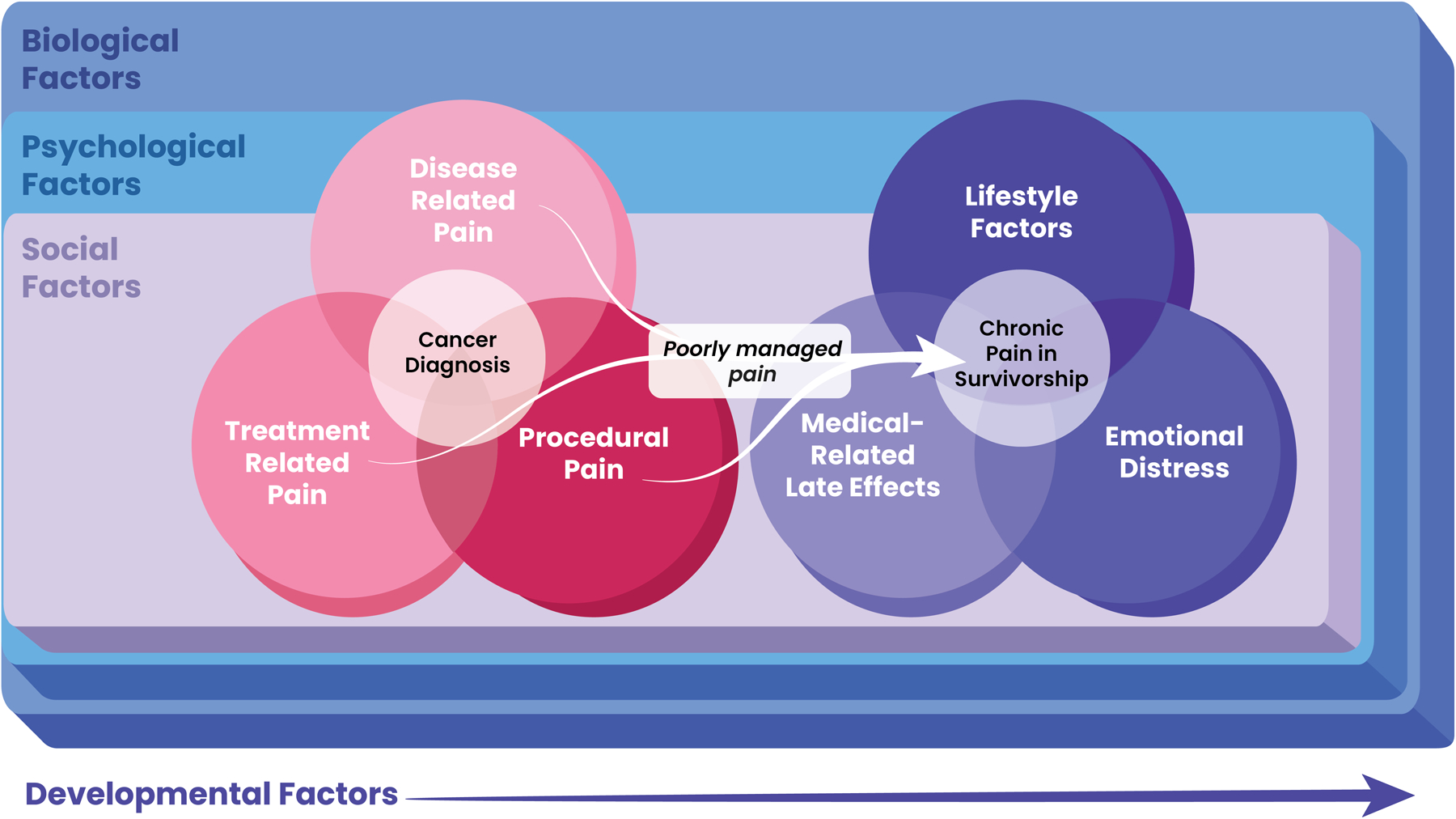

Pain among children and adolescents has been conceptualized using a biopsychosocial framework.4 This framework proposes that there are bidirectional relationships among biological (e.g., sex), psychological (e.g., anxiety), and social (e.g., socioeconomic status) factors that contribute to the presence and impact of pain.5–7 More recently, Alberts and colleagues proposed a model of pain pathways specific to survivors of childhood cancer which considers the influence of a cancer diagnosis, disease- and treatment-related pain as well as procedural pain in the development of chronic pain among survivors.8 Despite the availability of these conceptual models, the literature focused on pain in survivors of pediatric cancer has centered on biomedical risk factors. The research examining the biopsychosocial factors related to pain requires further elucidation.

Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the available evidence of pain in survivors of childhood cancer through a systematic review of the literature. The objectives of this review were to: (i) characterize the prevalence of pain (including chronic pain) in survivors of childhood cancer after completion of treatment; (ii) describe what methods are being used to measure pain; (iii) examine associations between pain and biological/physical and psychosocial factors; and (iv) make specific recommendations for more rigorous research of pain among long-term survivors of childhood cancer.

Methods

Cochrane and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines for completion of systematic reviews were followed.9,10 In March 2016, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) Guideline Task Force on Neurocognitive and Psychosocial late-effects performed an extensive review of the literature to identify updates for the COG LTFU Guidelines (version 5.0). This review was updated for the current manuscript.

Databases searched included PubMed (Web-based), PsycINFO (EBSCO), EMBASE (Ovid), and Web of Science (Thomson Reuters). Full PubMed search parameters are available in the online material (see Supplementary Table 1 in Online-Only Materials). Search strategies for PsycINFO, EMBASE, and Web of Science were adjusted for the syntax appropriate for each database using a combination of thesauri and text words. Relevant articles published from January 1990 to August 2019 were included. Narrative and systematic reviews and meta-analyses on this topic were also evaluated to identify relevant original manuscripts, but the reviews themselves were not included in the current analysis. Dissertations, books, book chapters, editorials, letters, case studies and conference proceedings/abstracts were excluded.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were determined prior to manuscript selection. Eligible studies: 1) were original research; 2) included quantitative assessment of pain (including chronic pain); 3) were published in English; 4) included children diagnosed with cancer between 0–21 years of age; 5) described survivors of any age who were at least 5 years from diagnosis and/or 2 years from the completion of therapy; and 6) included a sample size > 20 (to avoid case studies). Studies that had a wide range of ages and/or intervals from diagnosis and treatment were retained only if the mean age and/or time interval included the aforementioned criteria.

Data extraction was completed according to the Late Effect Evidence Table (LEET) developed by the COG Late-Effects Guideline Task Force and included study design, median follow-up time, participation rate, and description of study objectives. Risk of bias was considered for each study using domains adapted from the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool10 including: selection/subject bias, attrition bias, instrumentation and missing data and reporting outcomes. Each category was labeled ‘low risk of bias’, ‘high risk of bias’ or ‘unclear’.10 Quality of evidence and strength of recommendations according to criteria from the Grading of Recommendations Assessment Development and Evaluation (GRADE) was completed.11 Specifically, evidence was graded according to three categories: 1) Level A, high level of evidence; 2) Level B, moderate to low level of evidence (e.g., risk factor is significant in >50% of studies); 2) Level C, very low level of evidence (e.g., risk factor is significant in <50% of studies). Data extraction and quality assessments were completed by one independent rater for each published study.

Results

Data Extraction

This review yielded 4,302 unique publications title/abstracts, of which 73 articles were included in the final review (Supplementary Figure 1). Disagreements were resolved in all cases through consensus. Reasons for further exclusion are presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

Quality Assessment

Quality assessment was completed for each study independently and by considering these four key criteria: 1) Selection/Subject bias; 2) Attrition; 3) Instrumentation and Missing data; and 4) Reporting Measurement outcomes (see Supplementary Table 2 in Online-Only Materials). Of the 73 studies reviewed, 36% reported low risk of bias with respect to selection/subject bias (n=26/73); 1% for attrition (n=1/73), 19% for instrumentation and missing outcomes (n=14/73) and 7% for reporting outcomes (n=5/73). GRADE assessments can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

GRADE Assessment for factors related to pain

| FACTOR ASSESSED | GRADE |

|---|---|

| DISEASE RELATED FACTORS | |

| Diagnosis | |

| Neuroblastoma | Level C (1/1 studies)20 |

| Brain tumor | Level C (1/1 studies35 |

| High-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia | Level C (1/1 studies)35 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | Level C (2/2 studies)31,34 |

| Germ cell tumor | Level C (1/1 studies)34 |

| Wilms’ tumor | Level C (2/2 studies)31,33 |

| Osteosarcoma | Level C (2/2 studies)33,36 |

| Soft-tissue sarcoma | Level C (1/1 studies)36 |

| Development of post-treatment meningioma | Level C (1/1 studies)32 |

| History of disease recurrence or progression | Level C (1/1 studies)37 |

| TREATMENT RELATED FACTORS | |

| Treatment | |

| Hemi-abdominal radiation in children with Wilms’ tumor | Level C (1/1 studies)33 |

| Hematopoietic stem cell transplant in children with neuroblastoma | Level C (1/1 studies)20 |

| Lower-extremity amputation in children with osteosarcoma | Level C (1/1 studies)33 |

| Abdominal radiation in children with soft-tissue sarcomas | Level C (1/1 studies)41 |

| Total knee replacement | Level C (1/1 studies)42 |

| Radiation33,37,64 | Level C (3/3 studies)38,45,46 |

| BIOLOGICAL FACTORS | |

| Age | |

| There is some evidence that younger age at diagnosis is associated with increased pain | Level C (3/4 studies)19,38–40 |

| There is some evidence to suggest that younger age at diagnosis is associated with increased pain in females but not males | Level C (1/1 studies)38 |

| There is some evidence that age at time of study is associated with pain | Level C (4/5 studies)23,37,40,41,46 |

| Sex | |

| There is evidence to suggest that females report more pain than males | Level A (9/9 studies)12,14,19,26,37,41,44–46 |

| PSYCHOLOGICAL FACTORS | |

| Sleep | |

| Some evidence suggests that pain is associated with excessive daytime sleepiness | Level C (1/1 studies)47 |

| Some evidence suggests that pain is associated with sleep difficulties | Level C (2/2 studies)47,49 |

| Fatigue | |

| There is evidence to suggest that pain is associated with increased fatigue | Level A (6/6 studies)14,30,36,40,47,48 |

| Psychological Distress | |

| Some evidence suggests that pain is associated with increased psychological distress | Level C (3/3 studies)51–53 |

| Body Image | |

| Some evidence suggests pain is associated with poorer body image | Level C (1/1 studies)50 |

| Sports/Physical Activity-related Self-confidence | |

| Some evidence suggests pain is associated with decreased sports/physical activity-related self-confidence | Level C (1/1 studies)50 |

| Anxiety | |

| Some evidence suggests pain is associated with increased anxiety | Level C (2/2 studies)38,53 |

| Depression | |

| Some evidence suggests pain is associated with increased depression | Level C (3/3 studies)40,51,53 |

| Suicidal Ideation | |

| Some evidence suggests that pain is associated with suicidal ideation | Level C (2/2 studies)54,55 |

| Quality of Life | |

| Evidence suggests that pain is associated with reduced quality of life | Level B (3/3 studies)37,56,57 |

| SOCIAL FACTORS | |

| SES | |

| Some evidence suggests lower SES is associated with increased pain | Level C (3/3 studies)33,46,53 |

| Ethnic Background | |

| Some evidence suggests that individuals of Hispanic or African American background is associated with increased pain | Level C (1/1 studies)19 |

| Educational Level | |

| Some evidence suggests lower educational level and not completing high school is associated with increased pain | Level C (3/3 studies)19,21,25 |

| Employment Status | |

| Some evidence suggests that current employment status is related to pain | Level C (1/1 studies)44 |

| Relationship Status | |

| Some evidence suggests that single status is associated with increased pain | Level C (2/2 studies)21,44 |

Note: Level A = high level of evidence; Level B = moderate to low level of evidence (e.g., risk factor is significant in >50% of studies); Level C = very low level of evidence (e.g., risk factor is significant in <50% of studies)

Data Synthesis

Descriptive Characteristics of Included Studies

Supplementary Table 2 in online-only materials provides descriptive characteristics of the studies included. Studies were largely observational, cross-sectional study designs (46.6% n=34) with the remainder categorized as observational, cohort (41.1%, n=30), observational, case control (11.0%, n=8) and finally non-experimental (1.3%, n=1). Three studies evaluated pain longitudinally (4.1%). Of all the studies reviewed, 32.9% (n=24) included a comparison group: healthy or population controls (n=10), siblings (n=13), and other cancer survivors (e.g., comparison of survivors with versus without meningioma, survivors with versus without chronic fatigue, and various diagnoses; n=3). The remaining 67.1% did not include any comparison sample. Sample size of studies ranged from 25 to 20,051 participants. Length of follow-up ranged from an average of 5.4 to 32.0 years after diagnosis. Among the current sample of studies reporting pain in their results, only 13 (17.8%) identified pain in their specific study objectives. Of these 13 studies, 3 utilized a comparison group in their analyses.

Objective 1: What is the Prevalence of Pain?

Only three studies investigated chronic pain according to its definition of pain lasting more than 3 months. The prevalence of chronic pain was identified in 11.0–43.9% of survivors.12–14 These three studies focused specifically on survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and lymphoma and focused specifically on chronic headache,22 chronic hip pain and/or chronic back pain in ALL survivors,21 or any type of chronic pain in lymphoma survivors.23 The study reporting on any type of chronic pain reported the highest prevalence. Only one of these studies included a control group.12 The overall occurrence of any pain reported across studies was between 4.3–75%15,16

Twenty-four studies included control groups. Of these, evidence suggested that survivors of childhood cancer are at higher risk of experiencing any occurrence of pain (GRADE Level B; 21/25 studies). Evidence from these studies generally suggests that survivors reported more pain compared to controls and population norms12,17–22 with the exception of five studies.23–27 Of these five studies, one found that survivors reported significantly less bodily pain than their healthy peers25 while the other four studies showed survivors had no significant differences in pain compared to controls.23,24,26,27 Importantly, the one study showing less bodily pain in cancer survivors compared to health peers was a sample comprised of 45% females in the cancer survivor sample vs. 55% females in the healthy peers.

Objective 2: Methods for Measuring Pain

Specific measures for measuring pain varied and most were self- or parent-proxy report (see Table 2). The most commonly used measures of pain were items created by the authors for the purpose of the study (45.2%) or items derived from health-related quality of life or health status questionnaires (42.5%). The majority of author-created measures were limited to only one or two items. Examples of items created by authors include: “Does your child currently have pain as a result of his/her cancer, leukemia, tumor or similar illness, or its treatment?”28,29 Only a small minority of studies (9.0%) used independent pain measures that have been validated in other populations. One study30 utilized an Algometer, a validated measurement of pain tolerance and pain sensitivity. However, this study only used the Algometer to measure pain sensitivity.

Table 2.

Frequency of measures of pain included in studies.

| Measure | # of studies using measure (%) |

|---|---|

| Author-created measures | 33 (45.2%) |

| Health-related quality of life or health status measures | 31 (42.5%) |

| Disease-specific measures | 9 (12.3%) |

| Valid pain measures | 7 (9.6%) |

| Chart review | 2 (2.7%) |

| Unclear | 2 (2.7%) |

Objective 3: Factors Related to Pain

To conceptualize the factors related to pain, we considered an adapted theoretical model that incorporates the conceptual model of pain among survivors of childhood cancer developed by Alberts et al. as well as the biopsychosocial model of pain (see Figure 1). We have subsequently summarized the available literature according to these factors below. The evidence related to these factors as evaluated using the GRADE criteria can be found in Table 1.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of factors associated with pain in survivors of childhood cancer

Disease-Related Pain

Disease related pain factors explored in the literature included diagnosis, treatment and age at diagnosis. Six studies reported on diagnosis, where survivors of germ cell tumor, high-risk ALL, neuroblastoma, Hodgkin lymphoma, Wilms tumor and osteosarcoma reported more pain compared to population norms as did survivors who developed subsequent meningioma compared to those who did not.20,31–35

Survivors of bone and soft tissue sarcomas were almost five times more likely to report cancer-related pain compared to survivors of leukemia in one study.36 Another study found that brain tumor survivors reported experiencing more pain than those diagnosed with ALL treated on a standard- or high-risk protocol, as well as those diagnosed with a solid tumor.35 Finally, one study found that history of disease recurrence or progression was significantly related to pain.37

There was conflicting evidence that age at diagnosis was related to pain where three studies found that younger age was significantly related to increased reports of pain19,38,39 and one study found no association between age at diagnosis with pain.40

Treatment-Related Pain

Children diagnosed with Wilms tumor who had hemi-abdominal radiation, children with neuroblastoma treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), children with osteosarcoma who had lower-extremity amputation, and children diagnosed with soft-tissue sarcomas who underwent abdominal radiation were all more likely to report more pain during survivorship compared to their survivor peers who did not receive these therapies.20,33,41

Hsiao and colleagues35 found that ALL survivors who were treated on a high-risk protocol reported experiencing significantly greater pain than survivors treated on a standard-risk protocol,35 whereas Meeske and colleagues found no associations between pain with treatment in survivors of ALL.40 Survivors who had undergone total knee replacement surgery were also more likely to report pain in their limbs than survivors who had undergone other surgical procedures.42 Additionally, radiation therapy was found to put survivors at increased risk for pain.37 Another study explored small-fiber toxicity and pain sensitization in survivors of ALL and discovered survivors with increased pain sensitization suffered from at least two or three losses of quantitative sensory testing parameters.43

Biological Factors

Biological factors explored in relation to pain included age and sex. There was robust evidence in the current literature to support that females report significantly more pain than males.12,14,19,26,37,41,44–46 Data supporting age at the time of study was inconsistent where one study found pain to be negatively associated with age23 and other studies found pain to be positively associated with age.40,41,46 Recklitis and colleagues37 separated survivors into three different age groups and found that survivors who were currently 13–17 years of age had a higher frequency of pain than those who were 18–22 years of age, but not those who were 23–31 years.37 Interestingly, Cox et al.38 found that younger age at diagnosis was associated with pain in male survivors, but not female survivors.38

Psychological Factors

Psychological factors examined in the literature included sleep, fatigue, emotional distress, and quality of life. Fatigue and daytime sleepiness were consistently positively related to pain.14,30,36,40,47,48 Sleep difficulties were also found to be associated with increased reports of pain.47,49 With respect to emotional distress, one study found pain was associated with poorer body image and sports/physical activity-related self-confidence50 and another found that headaches were associated with emotional symptoms affecting daily activities and work.14 Pain was positively associated with global emotional distress,51–53 anxiety,38,53 depression,40,51,53 and suicidal ideation.54,55 Finally, it was generally found that more pain was significantly related to decreased health related quality of life (HRQL).56,57 Importantly, survivors who reported experiencing cancer-related pain were also more likely to report unmet information needs for managing pain as well as fear of cancer recurrence.36

Social Factors

Only 5 studies examined social factors related to pain in the current sample. Survivors’ with lower socioeconomic status (SES) had increased reports of pain33,46,53 as well as survivors’ with lower educational attainment25 or not completing high school.19,21 Other social factors related to increased pain included identifying as Hispanic or African American,19 single relationship status19,21 and being unemployed.19

Objective 4: Recommendations for future research in pain among survivors of childhood cancer

Based on the existing literature, and more specifically the gaps in the existing literature, the authors have considered areas for future research in pain among survivors of childhood cancer. These recommendations are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Directions for future research

| Directions for Future Research | |

|---|---|

| Background |

|

| Measurement |

|

| Research Design |

|

| Factors Related to Pain |

|

| Intervention |

|

| Clinical Care |

|

Discussion

The aims of the current review were to characterize the prevalence of pain (including chronic pain) in survivors of childhood cancer, describe the measurement of pain, examine factors associated with pain and provide recommendations for future work in this field. The results of this study revealed significant gaps in the assessment of pain among survivors of childhood cancer, which has led to a wide range of prevalence rates reported among the literature, limiting our understanding of pain in this vulnerable population. The majority of the included studies reported pain outcomes based on a single item or very few items and not using theoretically-grounded, multidimensional measurements of pain. In addition, rigorous, high quality studies assessing pain among this population are limited.

Importantly, we have proposed a conceptual model that amalgamates two existing pain frameworks7,8 in an attempt to capture the complex contributions to pain among this unique population. Based on our review, with respect to the factors found to be related to pain, only a few factors emerged consistently in their relationship to pain. Females were more likely to report pain than males, which is consistent with chronic non-cancer pain populations. Fatigue was also a prominent comorbid concern alongside pain in survivors of childhood cancer. These findings have important implications for developing interventions that target pain and fatigue concurrently, which may also include components of sleep as well. The chronic non-cancer pain literature has demonstrated that pain may disrupt sleep and subsequently, lack of sleep may exacerbate pain, leading to a cycle that is hard to overcome.58 The only other factor that demonstrated a moderate level of evidence in its relationship to pain was quality of life. The finding that quality of life is related to pain highlights that perhaps regardless of prevalence rates, pain among survivors of childhood cancer negatively impacts the quality of survivorship thereby warranting intervention.

Strong evidence supports the use of behavioral interventions for the management of procedural pain59 in pediatric cancer patients and generally the most effective pain management approaches combine pharmacological approaches with psychosocial procedural preparation and intervention.60–62 There is little research that has been conducted with respect to interventions for chronic pain among survivors of childhood cancer, however, considerable evidence also supports the use of behavioral interventions for the management of chronic pain among non-cancer populations.63 Certainly, given increasing concerns regarding the use of opioids to manage pain, attention must now turn to research focused on behavioral interventions specific to survivors of childhood cancer.

The remaining factors reported in the literature reviewed were considered to have very low evidence for their relationship to pain reinforcing our call to action for more work in this field. Certainly, based on the current review, pain has not been a priority in the pediatric cancer survivor literature, as evidenced by the absence of pain as a primary outcome in the majority of studies, and the use of one or two items driving analyses around pain outcomes. Accordingly, we wish to advocate for a commitment to future research in this field within the domains of: our background theoretical understanding of pain; improved measurement; enhanced research design; factors related to pain; intervention; and clinical care.

This review was not without limitations. To begin, we intentionally left our definition of pain broad to capture the broad range of studies that have assessed pain among survivors, however this limited our ability to be more specific in describing outcomes. In addition, as part of our search we excluded qualitative papers. Despite this, we acknowledge the strength of qualitative research to better capture the context of one’s experiences and provide greater perspective to quantitative findings. Finally, we acknowledge that within our review we did not take into account the era of treatment for studies reviewed. We are aware that treatment protocols have shifted significantly over the last several decades in favor of less toxic therapies and therefore we might expect differing prevalence rates of pain over time.

Conclusions

In summary, while there are a large number of studies that reported on pain in survivors of childhood cancer, the quality of pain assessment across these studies is quite poor, as evidenced by inconsistent findings and a large range of reported pain prevalence. Based on the results, it is important that future research on this topic utilize more comprehensive measures of pain as well as longitudinal designs in order to disentangle this complex, multidimensional construct. Deeper understanding of pain experienced by this population will inform future research into tailored interventions that address the complex and unique histories of survivors of childhood cancer. Clinically, greater attention to the experience of pain is warranted during regular follow-up appointments.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank “Designs that Cell”, and specifically, Sarah Nersesian, for her design of Figure 1.

Funding Information: This work was supported in part by NCTN Operations Center Grant U10CA180886 and the NCTN Statistics & Data Center Grant U10CA180899.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health

Conflicts of Interest: None to declare.

References

- 1.Robison LL, Hudson MM. Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: life-long risks and responsibilities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2014;14(1):61–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. 2015;156(6):1003–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang IC, Brinkman TM, Kenzik K, et al. Association between the prevalence of symptoms and health-related quality of life in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the St Jude Lifetime Cohort study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(33):4242–4251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palermo TM. Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Chronic Pain in Children and Adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Palermo TM, Chambers CT. Parent and family factors in pediatric chronic pain and disability: an integrative approach. Pain. 2005;119(1–3):1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pillai Riddell R, Racine N, Craig KD, Campbell L. Psychological theories and biopsychosocial models in pediatric pain In: McGrath P, Stevens B, Walker S, Zempsky W, eds. The Oxford Textbook of Pediatric Pain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2013:85–94. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palermo TM, Valrie CR, Karlson CW. Family and parent influences on pediatric chronic pain: a developmental perspective. Am Psychol. 2014;69(2):142–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alberts NM, Gagnon MM, Stinson JN. Chronic pain in survivors of childhood cancer: a developmental model of pain across the cancer trajectory. Pain. 2018;159(10):1916–1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic reviews. 2015;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011;4. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2004;328(7454):1490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bowers DC, Griffith T, Gargan L, et al. Back Pain Among Long-term Survivors of Childhood Leukemia. Journal of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 2012;34:624–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johannsdottir IMR, Hamre H, Fossa SD, et al. Adverse Health Outcomes and Associations with Self-Reported General Health in Childhood Lymphoma Survivors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2017;6(3):470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sadighi ZS, Ness KK, Hudson MM, et al. Headache types, related morbidity, and quality of life in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a prospective cross sectional study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2014;18(6):722–729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feeny D, Leiper A, Barr RD, et al. The comprehensive assessment of health status in survivors of childhood cancer: application to high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Cancer. 1993;67(5):1047–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beer SJ, Menezes AH. Primary tumors of the spine in children. Natural history, management, and long-term follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1997;22(6):649–658; discussion 658–649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldsby RE, Liu Q, Nathan PC, et al. Late-occurring neurologic sequelae in adult survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):324–331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gurney JG, Ness KK, Rosenthal J, Forman SJ, Bhatia S, Baker KS. Visual, auditory, sensory, and motor impairments in long-term survivors of hematopoietic stem cell transplantation performed in childhood: results from the Bone Marrow Transplant Survivor study. Cancer. 2006;106(6):1402–1408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu Q, Krull KR, Leisenring W, et al. Pain in long-term adult survivors of childhood cancers and their siblings: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pain. 2011;152(11):2616–2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Portwine C, Rae C, Davis J, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life in Survivors of High-Risk Neuroblastoma After Stem Cell Transplant: A National Population-Based Perspective. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63(9):1615–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Punyko JA, Gurney JG, Scott Baker K, et al. Physical impairment and social adaptation in adult survivors of childhood and adolescent rhabdomyosarcoma: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivors Study. Psychooncology. 2007;16(1):26–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright MJ, Galea V, Barr RD. Self-perceptions of physical activity in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. Pediatric Exercise Science. 2003;15:191–201. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boman KK, Hoven E, Anclair M, Lannering B, Gustafsson G. Health and persistent functional late effects in adult survivors of childhood CNS tumours: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(14):2552–2561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang IC, Brinkman TM, Armstrong GT, Leisenring W, Robison LL, Krull KR. Emotional distress impacts quality of life evaluation: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(3):309–319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langeveld NE, Grootenhuis MA, Voute PA, de Haan RJ, van den Bos C. Quality of life, self-esteem and worries in young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Psychooncology. 2004;13(12):867–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pogany L, Barr RD, Shaw A, Speechley KN, Barrera M, Maunsell E. Health status in survivors of cancer in childhood and adolescence. Qual Life Res. 2006;15(1):143–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sundberg KK, Doukkali E, Lampic C, Eriksson LE, Arvidson J, Wettergren L. Long-term survivors of childhood cancer report quality of life and health status in parity with a comparison group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55(2):337–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinkman TM, Ullrich NJ, Zhang N, et al. Prevalence and predictors of prescription psychoactive medication use in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(1):104–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brinkman TM, Zhang N, Ullrich NJ, et al. Psychoactive medication use and neurocognitive function in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(3):486–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zeller B, Loge JH, Kanellopoulos A, Hamre H, Wyller VB, Ruud E. Chronic fatigue in long-term survivors of childhood lymphomas and leukemia: Persistence and associated clinical factors. Journal of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 2014;36(6):438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Barr RD, Gonzalez A, Longchong M, et al. Health status and health-related quality of life in survivors of cancer in childhood in Latin America: A MISPHO feasibility study. International Journal of Oncology. 2001;19:413–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowers DC, Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, et al. Morbidity and Mortality Associated With Meningioma After Cranial Radiotherapy: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(14):1570–1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crom D, Chathaway D, Tolley E, Mulhern R, Hudson MM. Health Status and Health-related Quality of Life in Long-term Adult Survivors of Pediatric Solid Tumors. International Journal of Cancer. 1999:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimoda S, Horsman J, Furlong W, Barr R, de Camargo B. Disability and health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of cancer in childhood in brazil. Journal of Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 2008;30(8):563–570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsiao CC, Chiou SS, Hsu HT, Lin PC, Liao YM, Wu LM. Adverse health outcomes and health concerns among survivors of various childhood cancers: Perspectives from mothers. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2016;27(6):e12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelada L, Wakefield CE, Heathcote LC, et al. Perceived cancer-related pain and fatigue, information needs, and fear of cancer recurrence among adult survivors of childhood cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(12):2270–2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Recklitis CJ, Liptak C, Footer D, Fine E, Chordas C, Manley P. Prevalence and Correlates of Pain in Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Pediatric Brain Tumors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cox CL, Montgomery M, Oeffinger KC, et al. Promoting physical activity in childhood cancer survivors: results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2009;115(3):642–654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van Dijk EM, van Dulmen-den Broeder E, Kaspers GJ, van Dam EW, Braam KI, Huisman J. Psychosexual functioning of childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2008;17(5):506–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meeske KA, Siegel SE, Globe DR, Mack WJ, Bernstein L. Prevalence and correlates of fatigue in long-term survivors of childhood leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5501–5510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marina N, Hudson MM, Jones KE, et al. Changes in Health Status Among Aging Survivors of Pediatric Upper and Lower Extremity Sarcoma: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2013;94(6):1062–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Katsumoto S, Maru M, Yonemoto T, Maeda R, Ae K, Matsumoto S. Uncertainty in Young Adult Survivors of Childhood and Adolescent Cancer with Lower-Extremity Bone Tumors in Japan. Journal of Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology. 2019;8(3):291–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lieber S, Blankenburg M, Apel K, Hirschfeld G, Hernaiz Driever P, Reindl T. Small-fiber neuropathy and pain sensitization in survivors of pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2018;22(3):457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alessi D, Dama E, Barr R, et al. Health-related quality of life of long-term childhood cancer survivors: a population-based study from the Childhood Cancer Registry of Piedmont, Italy. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(17):2545–2552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arpaci T, Kilicarslan Toruner E. Assessment of problems and symptoms in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2016;25(6):1034–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hudson MM, Mertens A, Yasui Y, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhoood cancer: A report from the childhood cancer survivor study. Journal the American Medical Association. 2003;290(12):1583–1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rach AM, Crabtree VM, Brinkman TM, et al. Predictors of fatigue and poor sleep in adult survivors of childhood Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Cancer Surviv. 2017;11(2):256–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rueegg CS, Gianinazzi ME, Michel G, et al. Do childhood cancer survivors with physical performance limitations reach healthy activity levels? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2013;60(10):1714–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Berg C, Hayashi RJ. Participation and Self-Management Strategies of Young Adult Childhood Cancer Survivors. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2012;33(1):21–30. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boman KK, Hornquist L, De Graaff L, Rickardsson J, Lannering B, Gustafsson G. Disability, body image and sports/physical activity in adult survivors of childhood CNS tumors: population-based outcomes from a cohort study. J Neurooncol. 2013;112(1):99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brinkman TM, Zhu L, Zeltzer LK, et al. Longitudinal patterns of psychological distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109(5):1373–1381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.D’Agostino NM, Edelstein K, Zhang N, et al. Comorbid symptoms of emotional distress in adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2016;122(20):3215–3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oancea SC, Brinkman TM, Ness KK, et al. Emotional distress among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(2):293–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Recklitis CJ, Diller LR, Li X, Najita J, Robison LL, Zeltzer L. Suicide ideation in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(4):655–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Recklitis CJ, Lockwood RA, Rothwell MA, Diller LR. Suicidal ideation and attempts in adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3852–3857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Finnegan L, Campbell RT, Ferrans CE, Wilbur J, Wilkie DJ, Shaver J. Symptom cluster experience profiles in adult survivors of childhood cancers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009;38(2):258–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schultz KA, Chen L, Chen Z, et al. Health conditions and quality of life in survivors of childhood acute myeloid leukemia comparing post remission chemotherapy to BMT: a report from the children’s oncology group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014;61(4):729–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1539–1552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kazak AE. Evidence-based interventions for survivors of childhood cancer and their families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2005;30(1):29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liossi C, White P, Hatira P. Randomized clinical trial of local anesthetic versus a combination of local anesthetic with self-hypnosis in the management of pediatric procedure-related pain. Health Psychol. 2006;25(3):307–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liossi C, White P, Hatira P. A randomized clinical trial of a brief hypnosis intervention to control venepuncture-related pain of paediatric cancer patients. Pain. 2009;142(3):255–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kazak AE, Penati B, Boyer BA, et al. A randomized controlled prospective outcome study of a psychological and pharmacological intervention protocol for procedural distress in pediatric leukemia. J Pediatr Psychol. 1996;21(5):615–631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Fisher E, Law E, Dudeney J, Palermo TM, Stewart G, Eccleston C. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic and recurrent pain in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;9:CD003968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Odame I, Duckworth J, Talsma D, et al. Osteopenia, physical activity and health-related quality of life in survivors of brain tumors treated in childhood. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006;46(3):357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barr RD, Furlong W, Dawson S, et al. An assessment of global health status in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. Am J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1993;15(3):284–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berg C, Neufeld P, Harvey J, Downes A, Hayashi RJ. Late effects of childhood cancer, participation, and quality of life of adolescents. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health. 2008;29(3):116–124. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brinkman TM, Li C, Vannatta K, et al. Behavioral, Social, and Emotional Symptom Comorbidities and Profiles in Adolescent Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(28):3417–3425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chordas C, Manley P, Merport Modest A, Chen B, Liptak C, Recklitis CJ. Screening for pain in pediatric brain tumor survivors using the pain thermometer. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 2013;30(5):249–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Crom DB, Smith D, Xiong Z, et al. Health status in long-term survivors of pediatric craniopharyngiomas. J Neurosci Nurs. 2010;42(6):323–328; quiz 329–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Greenberg DB, Goorin A, Gebhardt MC, et al. Quality of life in osteosarcoma survivors. Oncology (Williston Park). 1994;8(11):19–25; discussion 25–16, 32, 35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Heden L, Poder U, von Essen L, Ljungman G. Parents’ perceptions of their child’s symptom burden during and after cancer treatment. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46(3):366–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kalafatcilar AI, Tufekci O, Oren H, et al. Assessment of neuropsychological late effects in survivors of childhood leukemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;31(2):181–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kanabar DJ, Attard-Montalto S, Saha V, Kingston JE, Malpas JE, Eden OB. Quality of life in survivors of childhood cancer after megatherapy with autologous bone marrow rescue. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1995;12(1):29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Khan RB, Hudson MM, Ledet DS, et al. Neurologic morbidity and quality of life in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia: a prospective cross-sectional study. J Cancer Surviv. 2014;8(4):688–696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kimberg CI, Klosky JL, Zhang N, et al. Predictors of health care utilization in adult survivors of childhood cancer exposed to central nervous system-directed therapy. Cancer. 2015;121(5):774–782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kranick SM, Campen CJ, Kasner SE, et al. Headache as a risk factor for neurovascular events in pediatric brain tumor patients. Neurology. 2013;80(16):1452–1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mertens A, Walls R, Taylor L, et al. Characteristics of childhood cancer survivors predicted their successful tracing. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(9):933–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mertens A, Sencer S, Myers C, et al. Complementary and alternative therapy use in adult survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2008;50(1):90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nayiager T, Duckworth J, Pullenayegum E, et al. Exploration of Morbidity in a Serial Study of Long-Term Brain Tumor Survivors: A Focus on Pain. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2015;4(3):129–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Nayiager T, Anderson L, Cranston A, Athale U, Barr RD. Health-related quality of life in long-term survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood and adolescence. Qual Life Res. 2017;26(5):1371–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ness KK, Hudson MM, Jones KE, et al. Effect of Temporal Changes in Therapeutic Exposure on Self-reported Health Status in Childhood Cancer Survivors. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(2):89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nixon Speechley K, Maunsell E, Desmeules M, et al. Mutual concurrent validity of the child health questionnaire and the health utilities index: an exploratory analysis using survivors of childhood cancer. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1999;12:95–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Phillips SM, Padgett LS, Leisenring WM, et al. Survivors of childhood cancer in the United States: prevalence and burden of morbidity. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(4):653–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Recklitis CJ, Liptak C, Footer D, Fine E, Chordas C, Manley P. Prevalence and Correlates of Pain in Adolescent and Young Adult Survivors of Pediatric Brain Tumors. J Adolesc Young Adult Oncol. 2019;8(6):641–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Revel-Vilk S, Menahem M, Stoffer C, Weintraub M. Post-thrombotic syndrome after central venous catheter removal in childhood cancer survivors is associated with a history of obstruction. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2010;55(1):153–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schwartz LA, Mao JJ, Derosa BW, et al. Self-reported health problems of young adults in clinical settings: survivors of childhood cancer and healthy controls. J Am Board Fam Med. 2010;23(3):306–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Szilagy I, Nagele E, FurschuB C, et al. Influencing factors on career choice and current occupation analysis of adult survivors of childhood cancer: a special focus on health-related occupations. Magazine of European Medical Oncology. 2019;12:83–90. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Van Schaik CS, Barr RD, Depauw S, Furlong W, Feeny D. Assessment of health status and health-related quality of life in survivors of Hodgkin’s disease in childhood. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1999;12:32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zebrack BJ, Chesler MA. Quality of life in childhood cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2002;11(2):132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zeller B, Loge JH, Kanellopoulos A, Hamre H, Wyller VB, Ruud E. Chronic fatigue in long-term survivors of childhood lymphomas and leukemia: persistence and associated clinical factors. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2014;36(6):438–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zeller B, Ruud E, Havard Loge J, et al. Chronic fatigue in adult survivors of childhood cancer: associated symptoms, neuroendocrine markers, and autonomic cardiovascular responses. Psychosomatics. 2014;55(6):621–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.