Abstract

This study created a framework incorporating provider perspectives of best practices for early psychosocial intervention to improve caregiver experiences and outcomes after severe pediatric traumatic brain injury (TBI). A purposive sample of 23 healthcare providers from the emergency, intensive care, and acute care departments, was selected based on known clinical care of children with severe TBI at a level 1 trauma center and affiliated children's hospital. Semistructured interviews and directed content analysis were used to assess team and caregiver communication processes and topics, prognostication, and recommended interventions. Providers recommended a dual approach of institutional and individual factors contributing to an effective framework for addressing psychosocial needs. Healthcare providers recommended interventions in three domains: (1) presenting coordinated, clear messages to caregivers, (2) reducing logistical and emotional burden of care transitions, and (3) assessing and addressing caregiver needs and concerns. Specific family-centered and trauma-informed interventions included: (1) creating and sharing interdisciplinary plans with caregivers, (2) coordinating prognostication meetings and communications, (3) tracking family education, (4) improving institutional coordination and workflow, (5) training caregivers to support family involvement, (6) performing biopsychosocial assessment, and (7) using systematic prompts for difficult conversations and to address family needs at regular intervals. Healthcare workers from a variety of disciplines want to incorporate certain trauma-informed and family-centered practices at each stage of treatment to improve experiences for caregivers and outcomes for pediatric patients with severe TBI. Future research should test the feasibility and effectiveness of incorporating routine psychosocial interventions for these patients.

Keywords: family-centered care, traumatic brain injury

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality for children, and was responsible for >812,000 emergency department (ED) visits, 23,000 hospitalizations, and 2500 pediatric deaths in the United States in 2014.1 For patients with severe TBI who are treated in hospitals, long-term caregiver and patient outcomes can be impacted by interventions in critical care settings.2 TBI recovery is long and complex, and families can often leave intensive care without appropriate resources or knowledge for the level of care required.3 Patients with TBI often have difficulty accessing rehabilitation services, and caregivers can struggle logistically with care management.4,5 Caregivers also have significant emotional burden, resulting depression and post-traumatic symptoms.6 Although virtual interventions or interventions after hospitalization have shown some efficacy, caregiver–healthcare team interactions during hospitalizations offer a unique opportunity for early family and caregiver intervention that can impact future recovery.6,7 Immediate initiation of family/caregiver interventions to address psychosocial needs, in line with best practices for family-centered and trauma-informed care, may allow for improvement with coping, stress during hospitalization, access to resources, rapport with the healthcare team, and potentially long-term care outcomes for both the patient and family.3 However, specific guidelines for psychosocial care of patients and families with severe TBI have not been developed.

There are national guidelines for inpatient pediatric TBI management that were issued in 2003 and then revised in 2012.8,9 These guidelines defined specific medical benchmarks for interventions based on best available evidence. Adherence to these guidelines has been shown to significantly improve survival and Glasgow Outcome Scales scores, especially when an interdisciplinary team was involved with care management.10,11 The Pediatric Guideline Adherence and Outcomes (PEGASUS) program, which has been tested at a level 1 pediatric trauma center, provides an integrated clinical care pathway and utilizes a protocol that provides daily checklists of evidence-based clinical practice, an accessible approach to care early in the course of TBI.11,12

Although provider perspectives on barriers to guideline adherence have been reported,13 psychosocial interventions, caregiver functioning, caregiving tasks, and coping have not, creating an opportunity to further improve the implementation and successes of severe TBI care. Studies in other domains have shown that incorporating provider perspectives into psychosocial interventions can lead to improved outcomes for patients, caregivers, and providers. One study examined a nursing-driven family-centered care intervention in the pediatric intensive care unit, and noted significant improvements in patient and caregiver experiences.14 Another intervention for end-of-life goals of care conversations noted that incorporating both family and provider feedback greatly improved occurrence, documentation, and quality of those discussions.15 Although family and patient feedback may define the desired outcomes of an intervention, providers' input can be especially valuable for optimizing structural and institutional interventions. We aimed to understand healthcare provider perspectives and create a framework for incorporating provider perspectives of best practice early psychosocial interventions to improve experiences and outcomes after severe pediatric TBI.

Methods

The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) was used to define the scope of this study by identifying five domains to consider in implementation projects: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals, and process.16 The goal of this study was to better understand the latter four characteristics in order to create an optimal intervention. “Outer setting” refers to the structural characteristics in which an intervention takes place; “inner setting” refers to the cultural values of that setting; characteristics of the individuals describes the patients, caregivers, and providers; and process describes the characteristics of the implementation process itself. The CFIR is an appropriate tool to better define barriers and facilitators to implementing a psychosocial intervention.

Patients with severe TBI at the study sites begin the PEGASUS pathway and are treated in four sequential care settings from which the study sample was drawn: the ED, pediatric intensive care unit (PICU), acute care hospitalization at a level 1 pediatric trauma center, and inpatient rehabilitation at a nearby affiliated children's hospital. An institutional review board (IRB) waiver was granted for this study.

This study utilized semistructured, in-person interviews to explore the experience of providers who interact with caregivers of children with severe TBI. Qualitative methods were utilized because of this study's goals of understanding in-depth provider perspectives for optimal design of psychosocial interventions for their patients with TBI. Interviews are ideal for achieving these goals, as they allow for more nuanced exploration of provider insight that might guide both interventions and future studies. Semistructured interviews ensured that all relevant concerns were systematically addressed, while allowing providers to offer novel solutions. By asking scripted, open-ended questions that allowed for follow-up questions, investigators could optimize the information learned from each interview. CFIR was used as a framework to ensure that barriers and facilitators to interventions could be comprehensively addressed.

The semistructured interview guide was written in an iterative format. First, a literature review informed the domains to be explored by clarifying family and caregiver insight into desired interventions, prior interventions to improve care of severe pediatric TBI, and psychosocial concerns specific to severe pediatric TBI. Next, the survey authors consulted with content experts both on the authorship team and otherwise affiliated with the care of pediatric patients with severe TBI to ensure that questions were clear and relevant, and that they invited creative responses. Interview domains included: caregiver communication topics, team and caregiver communication process, prognostication, and assessment and intervention with vulnerable families. Ideas and current practices for psychosocial interventions were explored. Example questions included: “When and how are psychosocial needs discussed in your setting? Can you describe a recent case?”; “How do you respond to questions about prognosis before definitive information is known?”; “What do you wish families knew sooner?” These questions invited active, relevant participation and often lead to follow-up questions regarding specific interventions.

Healthcare providers were selected using a purposive sampling method based on known involvement in the care of pediatric patients with severe TBI.17 Participants were selected to represent a variety of practice settings (e.g. rehabilitation, PICU, ED) and years of experience, as it was important to understand challenges and insights from the perspective of both new and experienced providers. Investigators estimated a sample size of 20–25 providers based on previous studies with a similar population. Approximately 30 providers were contacted for an interview via e-mail. Although no providers refused an interview, scheduling was a barrier for some participants. Interviews were conducted to a point of saturation; that is, new subjects were interviewed until it was determined that interview content had become repetitive.

Interviews were primarily conducted face to face, with three conducted via video conference. Twenty-one interviews were iteratively coded. Two interviews were not formally coded. One interview, with a senior, clinically experienced pediatric physiatrist, was used to revise the interview guide as described. A second interview was not recorded because of an equipment malfunction, although notes were carefully recorded. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analyzed iteratively using directed content analysis in Dedoose, a software program that allows for close analysis of interviews by tagging words or sentences with user-generated themes. Each interview was manually reviewed and major themes were identified, with special attention paid to implementation-impacting factors. The first author conducted a primary line-by-line analysis of interviews and the corresponding author coded a subset of interviews, identifying preliminary themes and patterns. After major themes were identified, interviews were revisited and more cohesively coded with Dedoose, allowing for specific quotes and proposed interventions to be identified. This iterative process allowed for continuous refining and analysis of interview content. The research team then reviewed the primary analysis and identified themes and potential interventions (provider-oriented and caregiver-oriented). Potential interventions were identified both explicitly based on direct recommendations from interview subjects and by the research team based on gaps in care identified over the course of interviews.

Reflexivity statement

In this study, researcher bias was carefully considered. The research team included a medical student with a background in social work, the principal investigator of the original PEGASUS pathway, a pediatric physiatrist who works extensively with the studied patient population, the nurse program manager of the PICU, and a social work researcher focused on psychosocial intervention implementation. Each researcher brought expertise, such as familiarity with the patient population and PEGASUS pathway, and also biases, such as extant opinions about next steps for psychosocial intervention and a strong investment in family-centered approaches to care. All researchers valued family-centered approaches and favored implementing psychosocial intervention at each stage of the pathway; these priorities were carefully considered with respect to collected data. The researchers considered their own biases when interpreting interviews and conducted member checking to maintain trustworthiness of data analysis.

Results

Twenty-three healthcare providers were interviewed. All healthcare providers reported caring for patients with severe TBI. In-person interviews were conducted by M.R.E., and ranged from 12 to 83 min (mean duration of 27.2 min).

Providers were from: ED (n = 4; three emergency medicine physicians and one social worker), pediatric intensive care unit (n = 13; two pediatric intensivists, one neurosurgeon, one nurse manager, two assistant nurse managers, one operations manager, five bedside nurses, and one social worker), and other (n = 6; one pediatric hospitalist, one pediatric neurologist, two pediatric neuropsychologists, and two pediatric physiatrists).

Eighteen (78%) providers only worked at the level 1 trauma center, whereas five also worked at a nearby affiliated children's hospital where patients receive in-patient rehabilitation and outpatient services.

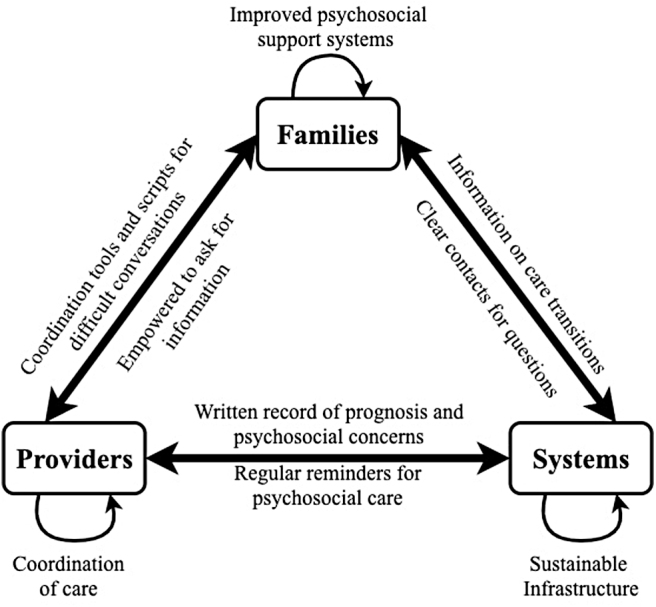

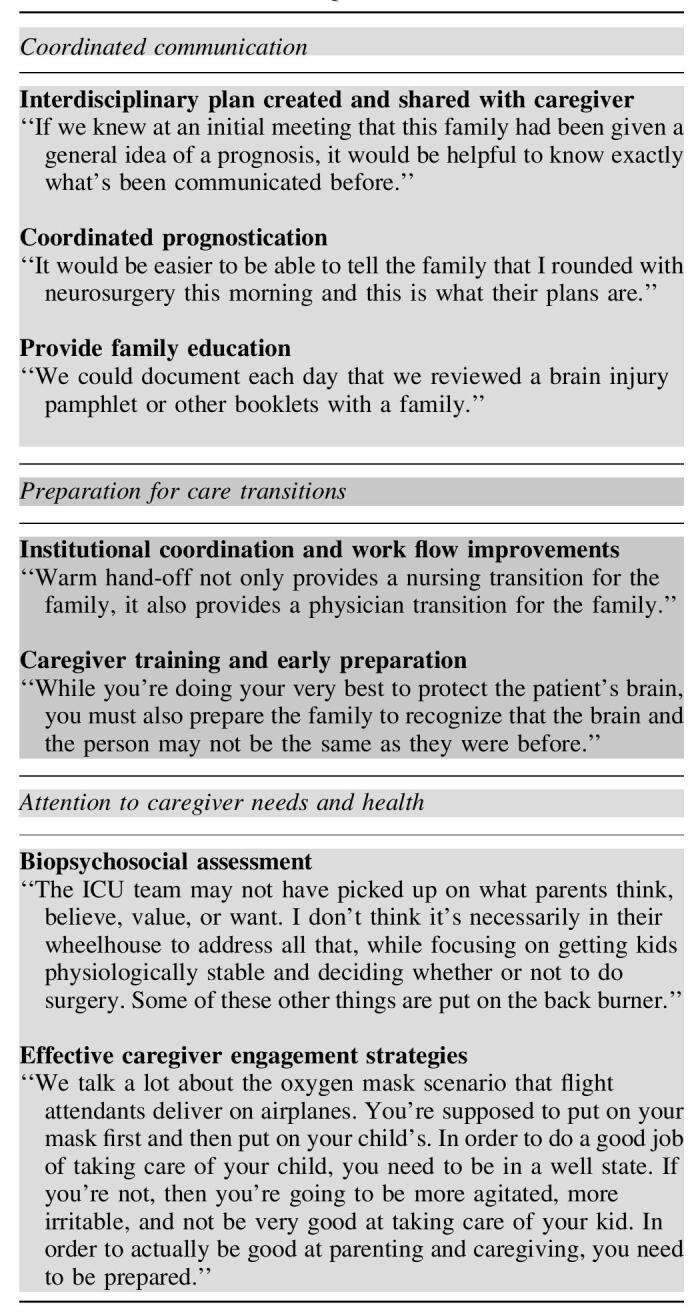

Providers recommended a dual approach using both institutional and individual factors that can provide a consistent framework for addressing psychosocial needs. Individual provider education was recommended (for example, providing potential scripting for unclear prognoses, or expanding provider education on care settings after transfer; see Figs. 1 and 2). Many participants routinely used particular explanations for challenging caregiver questions, and supported sharing these resources with other providers. However, providers often stated that it would be most helpful for changes to be made to the clinical care pathway itself to prompt psychosocial engagement with caregivers throughout the course of treatment. Sample quotes used to derive categories are represented in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Strengthening relationships among families, providers, and systems.

FIG. 2.

Timing of interventions to support psychosocial care.

Table 1.

Supportive Quotes Regarding Themes

Providers across all four locations of care had recommendations that could be grouped into three broad categories of intervention: coordinated communication, preparation for transitions, and attention to caregiver needs. A brief discussion of recommendations in each category follows. Figure 1 represents the intersection of these themes for families, providers, and systems. Figure 2 represents timing of suggested interventions.

Coordinated communication

Interdisciplinary plan created and shared with caregiver

Daily care goal planning was mentioned by most PICU providers as a particular challenge (Fig. 1). Interventions might include a paper goal sheet at bedside, an area in electronic health records (EHR) to input a daily plan, or a phone call between the PICU and neurosurgery attending physicians to confirm the daily plan for all patients with TBI. Interdisciplinary plans should be clearly established and readily available to all members of the care team and to caregivers.

Coordinated prognostication

The majority mentioned that coordinating communication around prognostication was uniquely challenging. Prognosis is often unclear in early stages of treatment and may change repeatedly during early stages of hospitalization. It is not uncommon for caregivers to receive conflicting information about survivability and recoverability. Prognostication should be relayed to caregivers only following a formal, interdisciplinary care conference, and families should, until then, receive coordinated messaging explaining the unique challenges of prognostication after severe TBI, an explanation of the role of the brain in functioning, and an explanation of care processes, monitoring, and the plan. Providers identified specific complex prognostication topics for which scripting might be particularly useful, including neuroplasticity; the diverse, highly variable, and complex neuropsychological sequelae after TBI; and the use of imaging. Key elements for scripts include: accessible language, small and manageable amounts of information, and acknowledgement of a wide and variable range of possibilities in outcomes if appropriate (see Table 1 for suggested scripts).

Provide family education. Family education was mentioned by 17/21 providers as another area in which more coordination may be helpful. Currently, a booklet is distributed to families explaining brain injury etiology, science, and treatment in simple English or Spanish. Many providers suggested adding a simple box to the bedside booklet that confirms that topics related to TBI were discussed with the caregiver. Although redundancy remains desired and necessary, the infrastructure provided by a daily checkbox of addressed educational topics and talking points related to the topics can assist in prompting both caregiver engagement and coordinated care.

Preparation for transitions

Institutional coordination and work flow improvements

ED interview subjects noted challenges when patients were transferred from another facility (Fig. 2). Families are often unaware that the stay in the ED could be lengthy, causing significant distress while they are waiting in the busy milieu of a level 1 trauma center. Suggestions included clarifying the goals of care shortly after arrival, and institutionally considering direct admissions for stable patients transferred from an outside hospital. Both ED and PICU providers suggested a “warm hand-off” from ED to PICU staff, with the transfer of care occurring in the presence of patients and families. Both ED and PICU providers also suggested the benefit of further information about the PICU providers becoming available in the ED.

Caregiver training and early preparation

Providers noted that families felt unprepared for transitioning to further stages of care, including acute care hospitalization and inpatient rehabilitation (Fig. 2). The intense provision of care in the PICU can be comforting for families and can prompt distress when children are moved to a less monitored care setting. Inpatient rehabilitation is provided in a separate hospital setting, providing an additional challenge for both families and staff to set clear expectations. Nine providers suggested changing the transfer process to include more explicit discussion of the next care setting, as well as amending the discharge or transfer paperwork to include specific contacts for follow-up questions.

Acute care hospitalization and rehabilitation cited similar opportunities for improvement regarding clarifying expectations of care settings and best assessments of longer-term prognoses. It would be beneficial for families to receive earlier familiarization with the scope and goals of care of the acute care hospital setting and inpatient rehabilitation. Interviews with rehabilitation providers also emphasized the importance of early preparation for long-term sequelae of TBI.

Attention to caregiver needs and health

Biopsychosocial assessment

Providers reported that families had significant extant psychosocial challenges, including unstable housing, limited English proficiency, and financial stressors. Rehabilitation medicine providers noted that an explicit psychosocial assessment was critical for goal-directed, family-centered care. PICU providers also noted the utility of ease of access of psychosocial information. An intervention to address this includes a brief psychosocial assessment of each family admitted to the PICU shortly after admission, and to make pertinent information readily accessible to staff in both the EHR and the written PEGASUS care pathway. For families that need additional supports, integrating care with social work, patient navigators, interpretation services, or other services is critical.

Effective caregiver engagement strategies

Better guidance for effective family/caregiver engagement throughout the course of care would be a helpful intervention. Although many nurses had established individual approaches with which they encouraged families to engage in their child's care, the styles and timelines varied. All providers noted that families appreciated opportunities to engage in meaningful ways. Providing a framework within the PEGASUS care pathway to provide patient-specific ways for families to safely participate in care can encourage further family participation and preparation for transfer and discharge (see Figure 1 for conceptual representation of engagement, support, and systemic structural changes).

Discussion

The aim of this study was to use provider insight to create a framework for early psychosocial intervention within an established severe pediatric TBI program. Primary findings suggest that incorporation of early psychosocial intervention is desired, and definable. Specific interventions targeting communication, transition planning, and caregiver support are suggested by healthcare workers and are included in the framework.

Extant literature shows that parents and caregivers of pediatric patients with severe TBI are in worse psychological health and experience more stress than their matched peers.18 Pediatric patients often require long-term, ongoing, interdisciplinary care, which poses significant logistical and psychological burdens to families and caregivers.19,20 Psychological burden on caregivers of children who survived TBI are higher when needs are unmet during recovery.20 In addition, previous research has clearly defined the disparities in both medical and psychosocial outcomes based on extant stressors, such as poverty, low medical literacy, and language barriers.2–5,12,13,18 For example, lower-income pediatric patients whose healthcare was covered by Medicaid had more unmet needs after severe TBI than children with private insurance.19 Addressing psychosocial care with a thorough assessment of both existing stressors and anticipated needs is vital to improving outcomes.

Psychosocial care during acute hospitalization has previously been found to impact the well-being of caretakers and families. Qualitative research mapping parent experiences during acute phase hospitalization showed that different stages of hospitalization require unique methods of engagement.7 Even caregivers of patients with limited recovery from severe TBI reported that they benefited significantly from supportive interactions with care providers during acute care hospitalization.21 Addressing psychosocial aspects of care during hospitalization can lay a groundwork for continued psychosocial engagement and progress throughout a patient's recovery.

Complete standardization of psychosocial care is neither possible nor desirable. However, PEGASUS succeeded as a clinical care pathway by providing specific, evidence-based benchmarks to prompt appropriate clinical intervention. By standardizing benchmarks of care, care providers could provide best-quality, evidence-based care, markedly improving outcomes. Adherence to clinical benchmarks significantly improved both survival to discharge and disposition upon discharge.11 This study adds to this prior work supporting algorithmic approaches to care by clarifying that providers benefit from and support the inclusion of psychosocial interventions into standard care pathways, as well as elucidating feasible systemic changes to advance that goal. The findings of provider interest in these changes as well as the clear definition of improvable domains are applicable and generalizable to sites not using a standardized protocol, as well as to patients on other non-TBI pathways for clinical care pathway care.

This study highlights the importance of provider and systemic engagement in psychosocial care and is aligned with previous research in family-centered care and trauma-informed care.2,13,22 Notably, previous research had caregiver-defined desired domains of improvement in communication, capacity building, and coordination.2 These domains were used to drive interview development for this study. A successful intervention is one that addresses family-defined desired outcomes while incorporating perspectives of providers most familiar with the infrastructure of the encompassing systems. It is notable that caregivers and providers have considerable overlap in desired improvements to care pathways. The contrast was in the framing of those improvements: whereas families emphasized desired outcomes, such as a clearer patient prognosis, the providers emphasized desired structural changes needed to arrive at the outcome, such as care conferences before sharing a prognosis.

Family-centered needs have been previously identified and with this study, we have more clearly defined those overlapping concerns of providers in delivering psychosocial care, as well as recommending solutions that are feasible and desirable. For example, patients interact with large care teams at each stage of care, presenting challenges in coordinating messaging between healthcare providers and families. With multiple teams involved in planning interventions, communicating expectations back to families can be a significant source of tension. This communication challenge was cited both in extant literature from families' perspectives, as well as in this study from providers' perspectives. Family suggestions were discussed with providers, who in turn suggested implementable solutions based on knowledge of underlying health systems and care pathways. Although family needs must drive psychosocial conversations, physician knowledge of the feasibility of implementation provides critical steps to creating sustainable changes in integrated psychosocial care.

Providers in this study recommend timing of these interventions, as well as elements of scripts to deal with difficult conversations. Domains were defined in this research that could not be defined exclusively through caregiver research, such as changes in infrastructure, additional desired trainings, and logistical approaches to care transition improvements. The recommendations provided here are micro (at provider level), mezzo (at hospital level), and macro (at protocol level) suggestions. Integrating support and engagement for caregivers of patients across all settings and timelines of care allows for a comprehensive and early approach to psychosocial care of caregivers and pediatric patients with severe TBI.

There are some study limitations. Demographics of responding providers were not collected. Future studies may wish to explore how provider demographics influence perceptions of psychosocial care and engagement with implementation of novel programs. This was a single center study. However, the national trends of improved survivability of severe TBI suggest that similar psychosocial considerations may be more universal.3 Although specific mechanisms for intervention (for example, expedited admission procedures) may need to be tailored to individual healthcare settings, the overarching themes of coordinated communication, improved care transfers, and attention to caregiver needs address universal themes in psychosocial intervention after severe pediatric TBI. The improved survival rates for pediatric patients with severe TBI under the PEGASUS program is a notable and remarkable achievement. It is vital to consider and address the quality of life of both pediatric patients with severe TBI and their caregivers, as additional medical progress is made in TBI survivability.

Conclusion

In summary, healthcare workers from a variety of disciplines recommended incorporating specific trauma-informed and family-centered practices at each stage of treatment to improve experiences for caregivers and outcomes for pediatric patients with severe TBI. Future research should test the feasibility and effectiveness of incorporating routine psychosocial interventions for children with severe TBI.

Funding Information

National Institutes of Health Research Education Program, Grant # R25HD094336-02.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1. HCUP Nationwide Emergency Department Sample (2014). Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville, MD. www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nedsoverview.jsp (Last accessed June11, 2020)

- 2. Moore, M., Robinson, G., Mink, R., Hudson, K., Dotolo, D., Gooding, T., Ramirez, A., Zatzick, D., Giordano, J., Crawley, D., and Vavilala, M.S. (2015). Developing a family-centered care model for critical care after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 16, 758–765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Braaf, S., Ameratunga, S., Christie, N., Teague, W., Ponsford, J., Cameron, P.A., and Gabbe, B. (2019). Care coordination experiences of people with traumatic brain injury and their family members in the 4-years after injury: a qualitative analysis. Brain Inj. 33, 574–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moore, M., Jimenez, N., Rowhani-Rahbar, A., Willis, M., Baron, K., Giordano, J., Crawley, D., Rivara, F.P., Jaffe, K.M., and Ebel, B.E. (2016). Availability of outpatient rehabilitation services for children after traumatic brain injury. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 95, 204–213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lever, K., Peng, J., Lundine, J.P., Caupp, S., Wheeler, K.K., Sribnick, E.A., and Xiang, H. (2019). Attending follow-up appointments after pediatric traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 34, E21–E34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Raj, S.P., Shultz, E.L., Zang, H., Zhang, N., Kirkwood, M.W., Taylor, H.G., Stancin, T., Yeates, K.O., and Wade, S.L. (2018). Effects of web-based parent training on caregiver functioning following pediatric traumatic brain injury: a randomized control trial. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 33, E19–E29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Reuter-Rice, K., Doser, K., Eads, J.K., and Berndt, S. (2017). Pediatric traumatic brain injury: families and healthcare team interaction trajectories during acute hospitalization. J. Pediatr. Nurs. 34, 84–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Carney, N.A., Chesnut, R.M., and Kochanek, P.M. (2003) Guidelines for the acute medical management of severe traumatic brain injury in infants, children, and adolescents. J. Trauma 54, S236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kochanek, P.M., Carney, N., Adelson, P.D., Ashwal, S., Bell, M.J., Bratton, S., Carson, S., Chesnut, R.M., Ghajar, J., Goldstein, B., Grant, G.A., Kissoon, N., Peterson, K., Selden, N.R., Tasker, R.C., Tong, K.A., Vavilala, M.S., Wainwright, M.S., and Warden, C.R. (2012). Guidelines for the Acute Medical Management of Severe Traumatic Brain Injury in Infants, Children, and Adolescents–Second Edition. Pediatr. Crit. Care Med. 13, S3–S5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vavilala, M.S., Kernic, M.A., Wang, J., Kannan, N., Mink, R.B., Wainwright, M.S., Groner, J.I., Bell, M.J., Giza, C.C., Zatzick, D.F., Ellenbogen, R.G., Boyle, L.N., Mitchell, P.H., and Rivara, F.P. (2014). Acute care clinical indicators associated with discharge outcomes in children with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit. Care Med. 42, 2258–2266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Vavilala, M.S., King, M.A., Yang, J.T., Erickson, S.L., Mills, B., Grant, R.M., Blayney, C., Qiu, Q., Chesnut, R.M., Jaffe, K.M., Weiner, B.J., and Johnston, B.D. (2019). The pediatric guideline adherence and outcomes (PEGASUS) programme in severe traumatic brain injury: a single-centre hybrid implementation and effectiveness study. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 3, 23–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rakes, L., King, M., Johnston, B., Chesnut, R.M., Grant, R., and Vavilala, M.S. (2016). Development and implementation of a standardized pathway in the pediatric intensive care unit for children with severe traumatic brain injuries. BMJ Qual. Improv. Rep. 5, u213581..w5431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Brolliar, S.M., Moore, M., Thompson, H.J., Whiteside, L.K., Mink, R.B., Wainwright, M.S., Groner, J.I., Bell, M.J., Giza, C.C., Zatzick, D.F., Ellenbogen, R.G., Boyle, L.N., Mitchell, P.H., Rivara, F.P., and Vavilala, M.S. (2016). A qualitative study exploring factors associated with provider adherence to severe pediatric traumatic brain injury guidelines. J. Neurotrauma 33, 1554–1560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Coats, H., Bourget, E., Starks, H., Lindhorst, T., Saiki-Craighill, S., Curtis, J.R., Hays, R., and Doorenbos, A. (2018). Nurses' reflections on benefits and challenges of implementing family-centered care in pediatric intensive care units. Am. J. Crit. Care 27, 52–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Curtis, J.R., Downey, L., Back, A.L., Nielsen, E.L., Paul, S., Lahdya, A.Z., Treece, P.D., Armstrong, P., Peck, R., and Engelberg, R.A. (2018). Effect of a patient and clinician communication-priming intervention on patient-reported goals-of-care discussions between patients with serious illness and clinicians: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern. Med. 178, 930–940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Damschroder, L.J., Aron, D.C., Keith, R.E., Kirsh, S.R., Alexander, J.A., and Lowery, J.C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 4, 50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Marshall M.N. (1996). Sampling for qualitative research. Fam. Pract. 13, 522–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hawley, C.A., Ward, A.B., Magnay, A.R., and Long, J. (2003). Parental stress and burden following traumatic brain injury amongst children and adolescents. Brain Inj. 17, 1–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Slomine B.S. (2006). Health care utilization and needs after pediatric traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics 117, e663–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aitken M.E., McCarthy M.L., Slomine B.S., Ding R., Durbin D.R., Jaffe K.M., Paidas C.N., Dorsch A.M., Christensen J.R., and Mackenzie E.J. (2009). Family burden after traumatic brain injury in children. Pediatrics 123, 199–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Keenan A., and Joseph L. (2010). The needs of family members of severe traumatic brain injured patients during critical and acute care: a qualitative study. Can. J. Neurosci. Nurs. 32, 25–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moore, M., Kiatchai, T., Ayyagari, R.C., and Vavilala M.S. (2017). Targeted areas for improving health literacy after traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 31, 1876–1881 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]