Abstract

The use and disposal of face masks, gloves, face shields, and other types of personal protective equipment (PPE) have increased dramatically due to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. Many governments enforce the use of PPE as an efficient and inexpensive way to reduce the transmission of the virus. However, this may pose a new challenge to solid waste management and exacerbate plastic pollution. The aim of the present study was to report the occurrence and distribution of COVID-19-associated PPE along the coast of the overpopulated city of Lima, Peru, and determine the influence of the activities carried out in each study site. In general terms, 138 PPE items were found in 11 beaches during 12 sampling weeks. The density was in the range of 0 to 7.44 × 10−4 PPE m−2. Microplastic release, colonization of invasive species, and entanglement or ingestion by apex predators are some of the potential threats identified. Recreational beaches were the most polluted sites, followed by surfing, and fishing sites. This may be because recreational beaches are many times overcrowded by beachgoers. Additionally, most of the PPE was found to be discarded by beachgoers rather than washed ashore. The lack of environmental awareness, education, and coastal mismanagement may pose a threat to the marine environment through marine litter and plastic pollution. Significant efforts are required to shift towards a sustainable solid waste management. Novel alternatives involve redesigning masks based on degradable plastics and recycling PPE by obtaining liquid fuels through pyrolysis.

Keywords: Coronavirus, Pollution, Microplastics, Mask, Gloves, Beach

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Plastic pollution is one of the greatest environmental challenges of the Anthropocene. Despite the significant efforts made by the scientific community, lawmakers, NGOs, and the general public, plastic pollution continues to exacerbate over time. Global plastic pollution reached 359 million tons in 2018 (PlasticsEurope, 2019), out of which a significant proportion is expected to reach the oceans (Avio et al., 2017). Conventional plastic polymers, such as polystyrene (PS), polyethylene (PE), polypropylene (PP), among others, are durable and strong materials (Andrady, 2011). Moreover, mismanagement of such materials will allow them to reach the ocean, thus becoming persistent pollutants in the marine environment.

Pollution with plastics cause adverse ecological, economic, and human health effects (De-la-Torre et al., 2021; Thompson et al., 2009). Large plastic debris has been observed to cause entanglement with marine biota, such as turtles and seabirds (Thiel et al., 2018). Plastics may be colonized by marine macroinvertebrates, many of which may be considered as alien invasive species, drift towards foreign ecosystems and cause biological invasions (Rech et al., 2018b, Rech et al., 2018a). Moreover, plastics break down into smaller particles (<5 mm), namely microplastics (MPs). MPs are now regarded as ubiquitous in the marine environment, found polluting coastal areas (Godoy et al., 2020; Hidalgo-Ruz et al., 2018), surface and sub-surface waters (Eriksen et al., 2018; Ryan et al., 2020), sediments (Castro et al., 2020; Neto et al., 2019), and being ingested by a wide range of taxa (De-la-Torre et al., 2020a; Ory et al., 2018, Ory et al., 2017; Santillán et al., 2020). MPs serve as a vector of chemical contaminants (Torres et al., 2021), thus producing ecotoxicological effects in organisms (He et al., 2021).

Amidst the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) is one of the most efficient and affordable ways to prevent the transmission of the virus. The use of PPE is not only recommended but also enforced to the public by multiple governments, resulting in a tremendous increase in the demand and consumption of PPE, mainly face masks (Prata et al., 2020). Mismanagement of PPE by frontline workers and citizens may lead to an increase in plastic pollution (Ardusso et al., 2021). Moreover, drawbacks in single-use plastic legislation have weakened the current progress towards a plastic-free development (Silva et al., 2020). For instance, in order to sustain the enormous demand of masks and other PPE, many single-use plastic legislations have been withdrawn or postponed. The current sanitary crisis threatens to severely increase plastic pollution, now introducing PPE as a potentially dominant type of marine litter.

In a recent report, it was estimated that 1.56 billion face masks likely entered in the oceans in 2020 (OceansAsia, 2020), which is a devastating number with severe detrimental effects on marine wildlife. Recent studies evidenced the occurrence of different types of PPE in coastal cities of South America (Ardusso et al., 2021), Lakes and beaches in Africa (Aragaw, 2020; Okuku et al., 2020), and cities in Europe (Prata et al., 2020). However, the current information is still insufficient to have a general overview of marine pollution with PPE associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. De-la-Torre and Aragaw (2021) discussed the potential distribution and effects of PPE in the marine environment and identified key research priorities. In order to address the lack of information about the source, abundance, and distribution of PPE in marine environments, the present study aimed to report the occurrence and distribution of COVID-19-associated PPE along the coast of the overpopulated city of Lima, Peru, and determine the influence of the activities carried out in each study site. To achieve this, standardized litter monitoring protocols were carried out between September and December 2020 in 11 well-distributed sites. The sites are representatives of three different activities (recreative, surfing, and fishing), and three sites regarded as control groups for comparison.

2. Method

2.1. Area of study

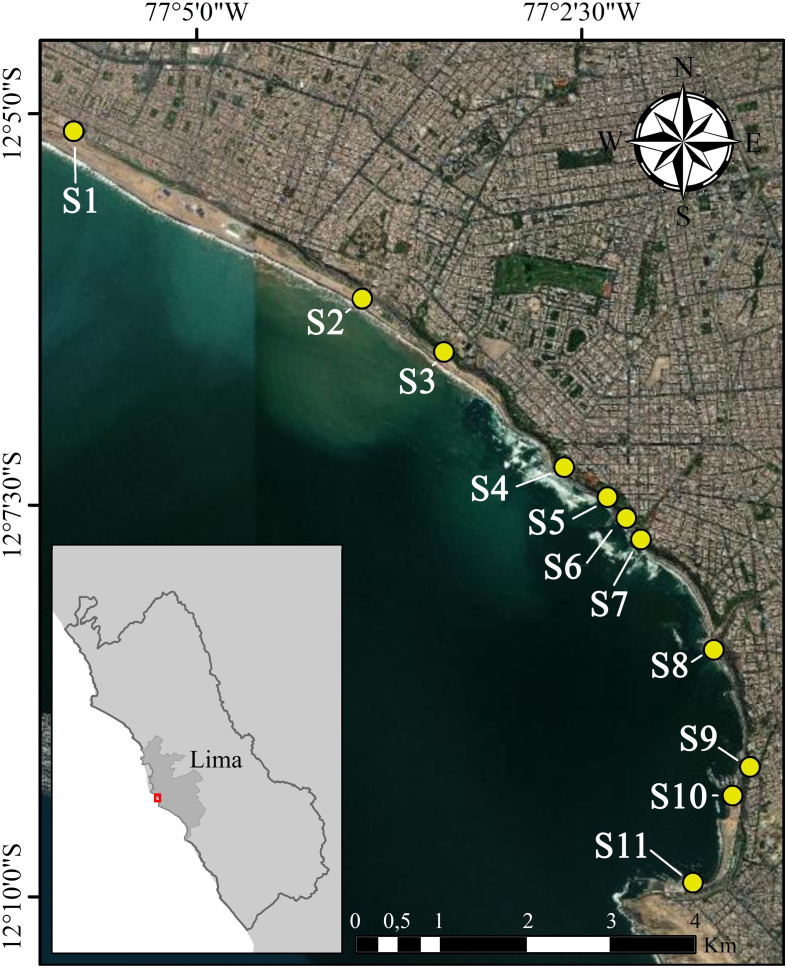

Lima is the capital city of Peru and one of the largest cities in the Americas, with a population of almost nine million. Due to the overpopulation and high business and industrial activities carried out in Lima, large quantities of solid waste are generated (Gilardino et al., 2017). Some beaches and coastal zones in Lima are recognized for their recreational, surfing, and gastronomic activities (Viatori and Scheuring, 2020). However, these activities represent a source of plastic and microplastic pollution entering the ocean (De-la-Torre et al., 2020b). The occurrence of PPE was carried out in 11 beaches in the city of Lima (Fig. 1 ), encompassing six districts. These sites were selected for being well distributed along the coast and representative of three activities that may influence the abundance of PPE. Sites S4 to S8 are regarded as beaches where surfing is the main activity. In sites, S9 and S10 general recreational activities are carried out by beachgoers, like sunbathing and swimming. Lastly, S11 is a small beach meant for artisanal fishing activities. These three activities are not mutually exclusive, which means that surfing can be carried out in S9 and S10, for example, but is less likely. These activities were assigned based on their popularity and field observations. Additionally, in S1 to S3, no activity is carried out and is of very difficult or restricted access. Hence, these three sites were treated as control groups.

Fig. 1.

Map of the region and sampling sites.

2.2. PPE monitoring

In order to sample PPE in each site, several transects were established covering the entirety of the beach. PPE were visually identified by walking along each transect. The number and length of transects varied according to the beach size and morphology. For instance, S10 was the site with the largest area (estimated 31,770 m2), and thus required more transects than S8 (estimated 10,730 m2) to be completely surveyed. The coordinates and estimated sampled area of each site are displayed in Table 1 . After identification, each PPE was photographed and classified as mask, face shield, glove, or other types of PPE. A total of 12 sampling campaigns were conducted during low tide in 12 consecutive weeks starting in September of 2020. The PPE items density was calculated using Eq. 1 (Okuku et al., 2020):

| (1) |

where C is the density of PPE per m2, n is the number of PPE counted, and a is the surveyed area.

Table 1.

Main activity, coordinates, and estimated area of each sampling site.

| Code | Activity | Substrate | Area covered |

|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | None (Difficult access) | Rock | 5620 m2 |

| S2 | None (Difficult access) | Rock | 7268 m2 |

| S3 | None (Difficult access) | Rock | 4296 m2 |

| S4 | Surfing | Rock | 7251 m2 |

| S5 | Surfing | Rock | 7217 m2 |

| S6 | Surfing | Rock | 4032 m2 |

| S7 | Surfing | Rock | 3234 m2 |

| S8 | Surfing | Rock | 10,730 m2 |

| S9 | Recreational | Sand | 22,987 m2 |

| S10 | Recreational | Sand | 31,770 m2 |

| S11 | Fishing | Sand | 6352 m2 |

2.3. Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses aimed to determine the influence of each activity on the density of PPE (PPE m−2 ± standard error of the mean). Each sampling campaign was considered as a replicate. Shapiro-Wilk and Kolmogorov-Smirnov tests invalidated the normal distribution of the data, hence non-parametric tests were applied. Kruskal-Wallis and Dunn's multiple comparisons tests were conducted to determine if significant differences existed between groups. The level of significance was set to 0.05. All the statistical analyses and graphs were performed in GraphPad Prism (version 8.4.3 for Windows).

3. Results and discussion

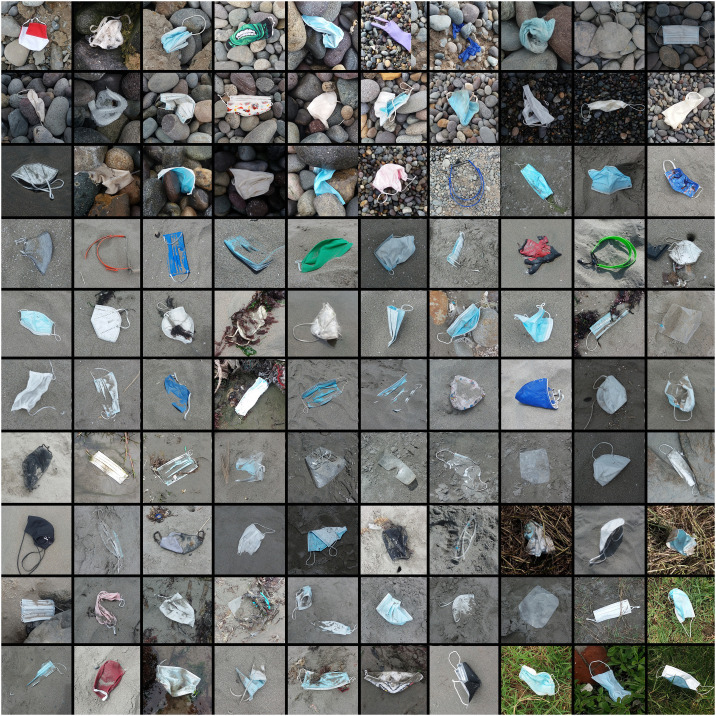

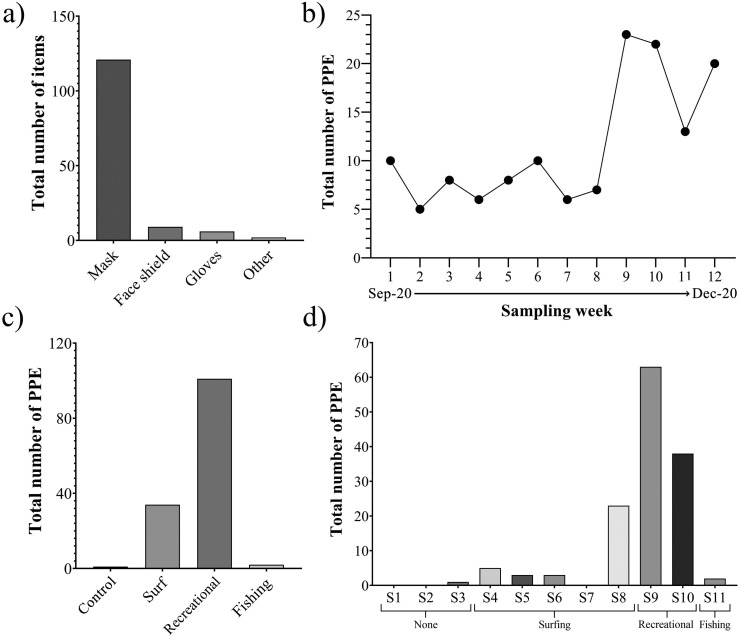

A total of 138 COVID-19-associated PPE items were counted in coastal zones. Fig. 2 displays 100 of the items found. Overall, masks were the most abundant type of PPE (87.7%), followed by face shields (6.5%), gloves (4.3%), and others (1.5%) (Fig. 3a). Out of the total masks, 54.5% were typical surgical masks, 12.4% were KN95, and the rest were cloth or unidentified mask types. A mean of 11.5 items (ranging from 5 to 23) was found in each sampling campaign. The occurrence of PPE seems to increase over time, as observed in Fig. 3b. In fact, 56.5% of the total number of items were found in the last four sampling campaigns. Although these sampling periods may not be sufficient to state that PPE pollution in continuously increasing over time, we hypothesize that the increase in the number of beachgoers during the summer season (November to March). Most items were found in recreational beaches (101 PPE items, representing 73.2% of the total items), followed by surfing beaches (34 PPE items, representing 24.6%) (Fig. 3c). In the control and fishing sites, only one and two items were found, respectively. Specifically, recreational beaches S9 and S10 were the two sites with the greatest number of PPE items, as displayed in Fig. 3d. Additionally to PPE, 26 wet wipes were counted during the sampling campaigns. Wet wipes or disinfectant wipes are used by the population as an alternative to maintain their goods clean and disinfected and, thus, are expected to be contaminating the marine environment. Although the use and disposal of wet wipes may be related to the COVID-19 pandemic, these are not considered as PPE as they are not wearable equipment.

Fig. 2.

Images of various types of PPE found in beaches of Lima, Peru.

Fig. 3.

Descriptive results from the PPE surveys. a) Accumulated number of PPE items found per type, b) total number of PPE items found in each sampling campaign, c) total number of PPE items found per type of activity, and d) accumulated number of PPE items in each sampling site.

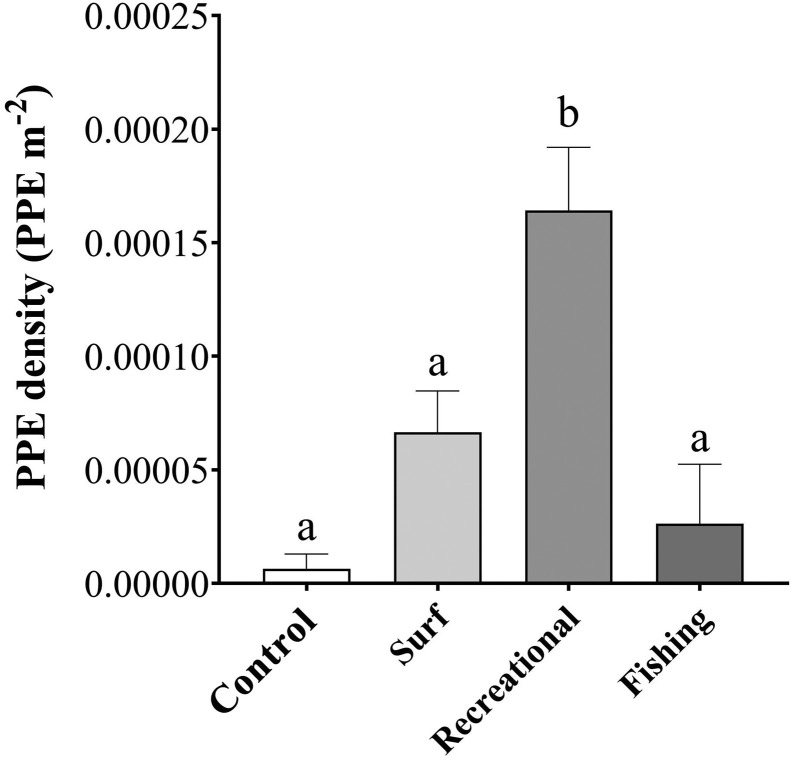

The overall mean PPE density was 6.42 × 10−5 ± 1.11 × 10−5 PPE m−2 (ranging from 0 to 7.44 × 10−4 PPE m−2). As expected, recreational beaches had the highest mean PPE density (1.64 × 10−4 ± 2.78 × 10−5 PPE m−2). Kruskal-Wallis test showed significant differences (Chi-square = 57.19, p ≤0.0001) in the PPE density among the three activities and the control (none). Dunn's multiple comparisons test indicated that the PPE density in recreational beaches differed significantly from surfing (p ≤0.0001), fishing (p ≤0.0001), and the control (p ≤0.0001). However, surfing was not significantly different from fishing (p ≥ 0.9999) and the control (p = 0.1005), as displayed in Fig. 4 .

Fig. 4.

Mean PPE density of the three groups of activities and control (none). Error bars indicate standard error of the mean (SEM) and letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

The first evidence of PPE pollution, such as photographs and videos, in coastal or urban environments appeared in social media, news outlets (Daley, 2020; Kassam, 2020), and reported by NGOs, like Oceans Asia (OceansAsia, 2020; Stokes, 2020). However, recent articles have reported the occurrence and density of PPE items in different environments (Table 2 ). Okuku et al. (2020) conducted standing stock surveys on beaches from Kenya focusing on PPE litter. The densities of PPE items in urban beaches ranged from 0 to 3.8 × 10−2 items m−2 and from 0 to 5.6 × 10−2 items m−2 in remote beaches. The higher densities in remote beaches were associated with the potential lack of compliance with the public beach closure, which was mandated by the local government. In the present study, the densities were lower in many orders of magnitude. This is probably due to the different sampling strategy carried out by Okuku et al. (2020). Aiming to have a better overview of the PPE pollution per beach, we survey the entirety of the area encompassing the whole length of the intertidal and supralittoral zones up to limit with the sidewalk/road or ~ 2 m into the vegetation. Thus, the area covered per sampling site was much larger, as listed in Table 1. Photographic evidence of PPE pollution in coastal environments from South America has been reported in Colombia, Chile, and Argentina (Ardusso et al., 2021). To the best of our knowledge, the study conducted by Okuku et al. (2020) and the present study are the only two that quantified the abundance and calculated the density of PPE items in beaches.

Table 2.

Summary of the reports and evidence of PPE pollution in natural and urban environments in different countries.

| Country | Environment | Results and observations | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peru | Beach | Documented and photographic evidence of PPE in urban beaches, Lima. Mean density of 6.42 × 10−5 PPE m−2, ranging from 0 to 7.44 × 10−4 PPE m−2. | This study |

| Colombia | Beach | Photographic evidence of face masks in Colombia Port, Santa Martha. | (Ardusso et al., 2021) |

| River | Photographic evidence of face masks in the water intakes of Roble River in Circasia, Quindío. | ||

| Chile | Beach | Photographic evidence of face masks and wet wipes in Amarilla beach, Antofagasta, and Papudo beach in Santiago de Chile. | |

| Argentina | Beach | Photographic evidence of face masks, medical containers, gloves, and face shields in Claromecó beaches, Bahía Blanca city, Buenos Aires. | |

| Brazil | City/urban | Photographic evidence of face masks in Imbituba city, Santa Catarina. | |

| Kenya | City/urban | COVID-19 PPE items were reported in 11 out of 14 monitored streets from the Kwale, Kilifi, and Mombasa counties. The COVID-19 litter density varied from 0 to ~0.3 items m−2. | (Okuku et al., 2020) |

| Beach | Low densities (ranging from 0 to 5.6 × 10−2 items m−2) were found in urban beaches from the three counties. Probably due to the restricted access to recreational beaches. | ||

| Surface water | No COVID-19-related items were found in the sampled sites. | ||

| Ethiopia | Lake | Photographic evidence of face masks in Lake Tana, Bahir Dar city. FTIR analysis determined the polymer composition of the masks as PP. | (Aragaw, 2020) |

| Indonesia | River | Litter was monitored (2016 and 2020) in Cilincing and Marinda rivers, Jakarta city. In 2016 no PPE litter was found. However, in 2020 different types of PPE, including masks, gloves, hazard suits, and face shields were reported in both rivers. | (Cordova et al., 2021) |

| Canada | City/urban | Photographic evidence of masks, gloves, wet wipes, and medical containers. | (Prata et al., 2020) |

| Portugal | |||

| Canada | City/urban | PPE litter was monitored in the city of Toronto. 1306 items were documented, mainly gloves (44%) and face masks (31%). The mean density was 1.01 × 10−3 items m−2, ranging from 0 to 8.22 × 10−3 items m−2. | (Ammendolia et al., 2021) |

| Nigeria | City/urban | Photographic evidence of masks along a highway and drainage in Ile-Ife. FTIR determined that the masks were mainly made of PP and HDPE. | (Fadare and Okoffo, 2020) |

The access to beaches in Peru was restricted from March to June 2020 as mandated by the local government. In June, the beaches gradually reopened for surfers and paddle surfers and later for beachgoers and recreational activities. By the end of October, the beaches were restricted again to beachgoers on Fridays, Saturdays, and Sundays to avoid agglomerations. These restrictions, however, had little influence on the occurrence and density of PPE in the sampled beaches. The notorious differences among activities and PPE densities may be attributed to the number of people arriving at each beach. During the sampling campaigns, it was noted that recreational beaches were packed with beachgoers on some occasions, while the number of surfers was significantly limited in comparison. Conversely, in the control sites (S1-S3) with difficult access, only a single face mask was identified in the strandline, along with other wood and EPS litter. This suggests that the mask in the control site may have been discarded elsewhere and drifted in the ocean currents towards this zone. Since most PPE items were found in the supralittoral zone, far from the high-tide line, it became evident that the majority of the items were brought by beachgoers and left on the beach. This behavior and lack of environmental awareness in beachgoers from Lima have been discussed before (De-la-Torre et al., 2020b), and attributed to marine pollution with PS litter and microplastics.

Like other types of abundant marine litter, PPE is expected to interact with marine biota. In the 11 sites, different species of seabirds were observed. Specifically, gulls from the Larus genus (Fig. S1), Peruvian pelicans (Pelecanus thagus) (Fig. S2), Inca terns (Larosterna inca), and Guanay cormorants (Leucocarbo bougainvillii). The presence of PPE that include elastic cords, such as face masks, poses a threat of entanglement to these species. PPE contaminated with SARs-CoV-2 could potentially become a conduit for reverse zoonotic transmission in marine mammals as reported for wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) (Mathavarajah et al., 2020). Moreover, from the few items that washed ashore rather than brought by beachgoers, two were colonized by red algae (Rhodophyta), as showed in Fig. S3. This indicates that masks may reach the oceans and become a suitable synthetic substrate for marine algae and potentially invertebrate animals. Depending on the buoyancy of the colonized items, PPE could become a vector of non-native species or AIS once it enters the ocean.

Particularly, PPE could become an important source of MPs. Face masks that are produced by electrospinning could easily release PP and PE micro- and nano-fibers to the environment (Aragaw, 2020; Fadare and Okoffo, 2020). Additionally, disinfectant wet wipes are a source of white microfibers too (Ó Briain et al., 2020). The detrimental effects of MPs have been strongly investigated, including co-exposure ecotoxicological assays with associated contaminants (Hariharan et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021; O'Donovan et al., 2020). All in all, the increasing demand, use, and incorrect disposal of PPE exacerbate the already critical plastic pollution from all the potential pollution pathways. To mitigate the environmental collateral damage caused by the current COVID-19 pandemic without compromising human health, Silva et al. (2020) recommends decoupling plastics from fuel-based resources, reducing single-use plastics and PPE, and optimizing waste management. These, however, may require significant long-term efforts on behalf of policymakers, scientists, and the public. In the specific case of Lima, since the main cause of PPE pollution is the lack of environmental awareness and education by the population, littering, and plastic pollution in natural environments should be supervised and penalized. On the other hand, Aragaw and Mekonnen (2021) proposes that PP and PVC PPE (namely, surgical mask and gloves) can be transformed into oil fuel via pyrolysis. Indeed, this strategy may serve as a potential recycling route for the vast amount of synthetic polymer-based PPE generated during the pandemic (Jain et al., 2020). New technologies for the development of bio-based PPE are expected to facilitate waste management (Ilyas et al., 2020; Rowan and Laffey, 2021). This may be a promising market and eco-friendly alternatives, as degradable biomaterials, such as polylactic acid (PLA) and starch-based composites, are generally less impacting than fossil fuel-based plastics (Rojas-Bringas et al., 2021).

In sites evaluated in the present study, periodic beach cleaning is carried out by the local governments (except in control sites). Hence, only a small portion of the waste generated by the beachgoers are expected to enter the ocean or interact with marine biota. This may cause our results to underestimate the weekly PPE generation but better represent the number of PPE at a certain time. During the sampling campaigns, PS trays were found bitten by gulls, possibly ingesting part of it (Fig. S4). No evidence of direct interaction (ingestion or entanglement) of PPE was observed with top predators. Nevertheless, the PS trays point out the availability of marine litter, including PPE, to biota. The overall mismanagement of the coastal areas, with a special focus on S9 and S10, along with the poor environmental education by beachgoers are the main drivers of marine litter and PPE pollution in the beaches of Lima.

4. Conclusion

The use of PPE as a preventive measure against SARS-CoV-2 transmission and subsequent incorrect disposal have exacerbated marine plastic pollution. In the present study, 11 beaches in the overpopulated city of Lima were monitored for COVID-19-associated PPE. Results indicated that the activity carried out on each beach significantly influences the density (items per m2) of PPE across the beach. Recreational beaches were the most polluted sites. This is associated with the high influx of beachgoers compared to beaches where the main activity is surfing or fishing. This new type of plastic pollution threatens marine top predators and could act as a vector of AIS, as well as a source of microplastics. In the case of Lima, littering and incorrect disposal of PPE is required to be supervised and penalized, as periodical beach cleaning may not be sufficient to safeguard the safety of the environment. Extended and long-lasting marine litter monitoring is required to set ground for the development of policy briefs aimed for a better PPE waste management in Peru. Additional alternatives recently investigated involve the recovery of liquid fuels from PPE waste through pyrolysis. This may be promising recycling route for PPE after recovery. Redesign of conventional PPE may include natural biodegradable materials, such as PLA and starch, to facilitate solid waste management. Also, promoting reusable masks is one important way to reduce the amount of solid waste generated. Given that the lack of environmental awareness is one of the important drivers of plastic pollution in Peru, long-term programs are required to shift citizens' behavior and encourage sustainable actions that could prevent plastic pollution in the future.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Gabriel E. De-la-Torre: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Supervision, Software, Project administration, Writing – original draft. Md. Refat Jahan Rakib: Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation. Carlos Ivan Pizarro-Ortega: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Diana Carolina Dioses-Salinas: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The corresponding author is thankful to Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola for financial support. Also, the authors are thankful to the five anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments and recommendations.

Editor: Damia Barcelo

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145774.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Ammendolia J., Saturno J., Brooks A.L., Jacobs S., Jambeck J.R. An emerging source of plastic pollution: environmental presence of plastic personal protective equipment (PPE) debris related to COVID-19 in a metropolitan city. Environ. Pollut. 2021;269:116160. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2020.116160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrady A.L. Microplastics in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2011;62:1596–1605. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2011.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragaw T.A. Surgical face masks as a potential source for microplastic pollution in the COVID-19 scenario. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020;159:111517. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aragaw T.A., Mekonnen B.A. Current plastics pollution threats due to COVID-19 and its possible mitigation techniques: a waste-to-energy conversion via pyrolysis. Environ. Syst. Res. 2021;10:8. doi: 10.1186/s40068-020-00217-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardusso M., Forero-López A.D., Buzzi N.S., Spetter C.V., Fernández-Severini M.D. COVID-19 pandemic repercussions on plastic and antiviral polymeric textile causing pollution on beaches and coasts of South America. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;763:144365. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avio C.G., Gorbi S., Regoli F. Plastics and microplastics in the oceans: from emerging pollutants to emerged threat. Mar. Environ. Res. 2017;128:2–11. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2016.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro R.O., da Silva M.L., Marques M.R.C., de Araújo F.V. Spatio-temporal evaluation of macro, meso and microplastics in surface waters, bottom and beach sediments of two embayments in Niterói, RJ, Brazil. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020;160:111537. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordova M.R., Nurhati I.S., Riani E., Nurhasanah, Iswari M.Y. Unprecedented plastic-made personal protective equipment (PPE) debris in river outlets into Jakarta Bay during COVID-19 pandemic. Chemosphere. 2021;268:129360. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.129360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley, B., 2020. Coronavirus face masks: an environmental disaster that might last generations [WWW Document]. Conversat. URL https://theconversation.com/coronavirus-face-masks-an-environmental-disaster-that-might-last-generations-144328 (accessed 1.31.21).

- De-la-Torre G.E., Aragaw T.A. What we need to know about PPE associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the marine environment. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2021;163:111879. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De-la-Torre G.E., Apaza-Vargas D.M., Santillán L. Microplastic ingestion and feeding ecology in three intertidal mollusk species from Lima, Peru. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2020;55:167–171. doi: 10.22370/rbmo.2020.55.2.2502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De-la-Torre G.E., Dioses-Salinas D.C., Castro J.M., Antay R., Fernández N.Y., Espinoza-Morriberón D., Saldaña-Serrano M. Abundance and distribution of microplastics on sandy beaches of Lima, Peru. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020;151:110877. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De-la-Torre G.E., Dioses-Salinas D.C., Pizarro-Ortega C.I., Santillán L. New plastic formations in the Anthropocene. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754:142216. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen M., Liboiron M., Kiessling T., Charron L., Alling A., Lebreton L., Richards H., Roth B., Ory N.C., Hidalgo-Ruz V., Meerhoff E., Box C., Cummins A., Thiel M. Microplastic sampling with the AVANI trawl compared to two neuston trawls in the Bay of Bengal and South Pacific. Environ. Pollut. 2018;232:430–439. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadare O.O., Okoffo E.D. Covid-19 face masks: a potential source of microplastic fibers in the environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;737:140279. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilardino A., Rojas J., Mattos H., Larrea-Gallegos G., Vázquez-Rowe I. Combining operational research and life cycle assessment to optimize municipal solid waste collection in a district in Lima (Peru) J. Clean. Prod. 2017;156:589–603. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.04.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Godoy V., Prata J.C., Blázquez G., Almendros A.I., Duarte A.C., Rocha-Santos T., Calero M., Martín-Lara M.Á. Effects of distance to the sea and geomorphological characteristics on the quantity and distribution of microplastics in beach sediments of Granada (Spain) Sci. Total Environ. 2020;746:142023. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan G., Purvaja R., Anandavelu I., Robin R.S., Ramesh R. Accumulation and ecotoxicological risk of weathered polyethylene (wPE) microplastics on green mussel (Perna viridis) Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021;208:111765. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2020.111765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Yang X., Liu H. Enhanced toxicity of triphenyl phosphate to zebrafish in the presence of micro- and nano-plastics. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;756:143986. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo-Ruz V., Honorato-Zimmer D., Gatta-Rosemary M., Nuñez P., Hinojosa I.A., Thiel M. Spatio-temporal variation of anthropogenic marine debris on Chilean beaches. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018;126:516–524. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y., Li W., Gao J., Wang F., Yang W., Han L., Lin D., Min B., Zhi Y., Grieger K., Yao J. Effect of microplastics on ecosystem functioning: microbial nitrogen removal mediated by benthic invertebrates. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;754:142133. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilyas S., Srivastava R.R., Kim H. Disinfection technology and strategies for COVID-19 hospital and bio-medical waste management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;749:141652. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain S., Yadav Lamba B., Kumar S., Singh D. Strategy for repurposing of disposed PPE kits by production of biofuel: pressing priority amidst COVID-19 pandemic. Biofuels. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1080/17597269.2020.1797350. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kassam, A., 2020. “More Masks than Jellyfish”: Coronavirus Waste Ends Up in Ocean [WWW Document]. Guard. URL https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/08/more-masks-than-jellyfish-coronavirus-waste-ends-up-in-ocean (accessed 1.31.21).

- Mathavarajah S., Stoddart A.K., Gagnon G.A., Dellaire G. Pandemic danger to the deep: the risk of marine mammals contracting SARS-CoV-2 from wastewater. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;143346 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neto J.A.B., Gaylarde C., Beech I., Bastos A.C., da Silva Quaresma V., de Carvalho D.G. Microplastics and attached microorganisms in sediments of the Vitória bay estuarine system in SE Brazil. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019;169:247–253. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2018.12.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ó Briain O., Marques Mendes A.R., McCarron S., Healy M.G., Morrison L. The role of wet wipes and sanitary towels as a source of white microplastic fibres in the marine environment. Water Res. 2020;182:116021. doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.116021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OceansAsia, 2020. COVID-19 Facemasks & Marine Plastic Pollution [WWW Document]. OceansAsia. URL https://oceansasia.org/covid-19-facemasks/ (accessed 1.31.21).

- O’Donovan S., Mestre N.C., Abel S., Fonseca T.G., Carteny C.C., Willems T., Prinsen E., Cormier B., Keiter S.S., Bebianno M.J. Effects of the UV filter, oxybenzone, adsorbed to microplastics in the clam Scrobicularia plana. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;733:139102. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuku E., Kiteresi L., Owato G., Otieno K., Mwalugha C., Mbuche M., Gwada B., Nelson A., Chepkemboi P., Achieng Q., Wanjeri V., Ndwiga J., Mulupi L., Omire J. The impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on marine litter pollution along the Kenyan coast: a synthesis after 100 days following the first reported case in Kenya. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020;111840 doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2020.111840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory N.C., Sobral P., Ferreira J.L., Thiel M. Amberstripe scad Decapterus muroadsi (Carangidae) fish ingest blue microplastics resembling their copepod prey along the coast of Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the South Pacific subtropical gyre. Sci. Total Environ. 2017;586:430–437. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ory N., Chagnon C., Felix F., Fernández C., Ferreira J.L., Gallardo C., Garcés Ordóñez O., Henostroza A., Laaz E., Mizraji R., Mojica H., Murillo Haro V., Ossa Medina L., Preciado M., Sobral P., Urbina M.A., Thiel M. Low prevalence of microplastic contamination in planktivorous fish species from the southeast Pacific Ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018;127:211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PlasticsEurope, 2019. Plastics-the Facts 2019 An analysis of European plastics production, demand and waste data.

- Prata J.C., Silva A.L.P., Walker T.R., Duarte A.C., Rocha-Santos T. COVID-19 pandemic repercussions on the use and management of plastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020;54:7760–7765. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.0c02178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rech S., Salmina S., Borrell Pichs Y.J., García-Vazquez E. Dispersal of alien invasive species on anthropogenic litter from European mariculture areas. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018;131:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rech S., Thiel M., Borrell Pichs Y.J., García-Vazquez E. Travelling light: fouling biota on macroplastics arriving on beaches of remote Rapa Nui (Easter Island) in the South Pacific subtropical gyre. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018;137:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2018.10.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas-Bringas P.M., De-la-Torre G.E., Torres F.G. Influence of the source of starch and plasticizers on the environmental burden of starch-Brazil nut fiber biocomposite production: a life cycle assessment approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;769:144869. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan N.J., Laffey J.G. Unlocking the surge in demand for personal and protective equipment (PPE) and improvised face coverings arising from coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic – implications for efficacy, re-use and sustainable waste management. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;752:142259. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.142259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan P.G., Suaria G., Perold V., Pierucci A., Bornman T.G., Aliani S. Sampling microfibres at the sea surface: the effects of mesh size, sample volume and water depth. Environ. Pollut. 2020;258:113413. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santillán L., Saldaña-Serrano M., De-la-Torre G.E. First record of microplastics in the endangered marine otter (Lontra felina) Mastozoología Neotrop. 2020;27:211–215. doi: 10.31687/saremMN.20.27.1.0.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva A.L.P., Prata J.C., Walker T.R., Campos D., Duarte A.C., Soares A.M.V.M., Barcelò D., Rocha-Santos T. Rethinking and optimising plastic waste management under COVID-19 pandemic: policy solutions based on redesign and reduction of single-use plastics and personal protective equipment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742:140565. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes G. OceanAsia; 2020. No Shortage Of Masks At The Beach - OCEANS ASIA [WWW Document]https://oceansasia.org/beach-mask-coronavirus/ URL. (accessed 10.27.20) [Google Scholar]

- Thiel M., Luna-Jorquera G., Álvarez-Varas R., Gallardo C., Hinojosa I.A., Luna N., Miranda-Urbina D., Morales N., Ory N., Pacheco A.S., Portflitt-Toro M., Zavalaga C. Impacts of marine plastic pollution from continental coasts to subtropical gyres-fish, seabirds, and other vertebrates in the SE Pacific. Front. Mar. Sci. 2018;5:238. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R.C., Moore C.J., vom Saal F.S., Swan S.H. Plastics, the environment and human health: current consensus and future trends. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2009;364:2153–2166. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres F.G., Dioses-Salinas D.C., Pizarro-Ortega C.I., De-la-Torre G.E. Sorption of chemical contaminants on degradable and non-degradable microplastics: recent progress and research trends. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;757:143875. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.143875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viatori M., Scheuring B. Saving the Costa Verde’s waves: surfing and discourses of race–class in the enactment of Lima’s coastal infrastructure. J. Lat. Am. Caribb. Anthropol. 2020;25:84–103. doi: 10.1111/jlca.12460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material