Abstract

The development of straightforward synthesis of regio- and stereodefined alkenes with multiple aliphatic substituents under mild conditions is an unmet challenge owing to competitive β-hydride elimination and selectivity issues. Herein, we report the nickel-catalyzed intermolecular cross-dialkylation of alkynes devoid of directing or activating groups to afford multiple aliphatic substituted alkenes in a syn-selective fashion at room temperature. The combination of two-electron oxidative cyclometallation and single-electron cross-electrophile coupling of nickel enables the syn-cross-dialkylation of alkynes at room temperature. This reductive protocol enables the sequential installation of two different alkyl substituents onto alkynes in a regio- and stereo-selective manner, circumventing the tedious preformation of sensitive organometallic reagents. The synthetic utility of this protocol is demonstrated by efficient synthesis of multi-substituted unfunctionalized alkenes and diverse transformations of the product.

Subject terms: Catalytic mechanisms, Homogeneous catalysis, Synthetic chemistry methodology

The synthesis of regio- and stereo-defined alkenes with multiple alkyl substituents is an unmet challenge. Here, the authors report a nickel-catalyzed intermolecular cross-dialkylation of alkynes devoid of directing or activating groups to afford multiple aliphatic substituted alkenes in a syn-selective fashion.

Introduction

Multiple substituted alkenes are pivotal subunits which are commonly occurring in natural products1–3, bioactive molecules4–7, and material sciences8, and serve as useful precursors for other functional groups and chiral centers9–12. In addition, alkenes exhibit orthogonal reactivity with respect to polar functional groups, providing an opportunity for the late-stage derivatization of complex molecules. To this end, synthesis of olefins with stereo-selectivity control has become one of the major themes in the arena of synthetic chemistry and has evolved from Wittig reaction and elimination reactions to carbometallation-coupling reactions13–15 and olefin metathesis16–18. Despite numerous progress in addressing this issue, stereodefined synthesis of tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes remains a formidable synthetic challenge. On the other hand, Ni-catalyzed carbo-difunctionalization of alkynes represents an ideal route to access multiple substituted alkenes with molecular complexity via the spontaneous formation of two vicinal C–C bonds. Among which, alkylation of alkynes is more challenging due to the difficulties in forging Csp2-Csp3 bond19–29. In general, three distinct strategies have been employed to address this issue. The first strategy is a Ni-catalyzed radical addition onto alkynes, followed by recombination and coupling with arylmetallic reagents, favoring anti-selectivity which is dominated by steric repulsion of vinyl radicals with nickel center (Fig. 1a, top)19–21. The use of terminal alkynes offers limited opportunity to afford trisubstituted alkenes. The second strategy is a carbometallation of alkynes to generate vinyl nickel species, which is followed by an electrophilic quench, favoring a syn-selectivity (Fig. 1a, bottom)22–31. This method suffers from regioselectivity issues, and could be only applied to electronically and sterically biased alkynes. In most cases, directing groups are required to improve regioselectivity. These two strategies require sensitive organometallic reagents, and can be applied to alkylarylation and diarylation of alkynes, dialkylation is inaccessible due to the difficulties in forming the second Csp2-Csp3 bond28. The other is oxidative cyclization of Ni (0) complex with alkyne and a second π-component to form Ni(II) cyclic intermediates, followed by σ-bond metathesis or transmetalation with organometallic reagents (Fig. 1b) to forge the second carbon-carbon bond. Montgomery32–40, Jamison41,42, Ikeda and Sato43, Ogoshi44,45, as well as others46–48 extensively investigated the tandem oxidative cyclization of alkynes with C = C/C = N/C = O and coupling using different organometallic reagents (R-M, M = Zn, B, Mg, Zr, Sn) to give diverse substituted alkenes (Fig. 1b, top). In 2018, Montgomery reported a seminal reductive Ni-catalyzed intramolecular oxidative cyclization of internal alkyne with aldehyde, followed by coupling with alkyl bromide to afford tetrasubstituted allylic ether with cyclic substituent (Fig. 1b, bottom)49. The reaction allows for the use alkyl halides as alkylating reagents instead of organometallic reagents. To the best of our knowledge, no general method for fully intermolecular cross-dialkylation of alkynes is developed, probably due to non-productive β-H hydride elimination during coupling process and competitive selectivity issues. In this context, we envisioned a fully intermolecular oxidative cyclometallation of alkyne with alkene50–56, followed by cross-electrophile coupling of alkyl halide to sequentially forge two Csp2-Csp3 bonds to deliver general tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes (Fig. 1c). This conceptual strategy arises several significant challenges: the nucleophilic addition of organonickel/zinc species onto enones, β-H elimination of alkylnickel intermediate, homocoupling/dehalogenation of alkyl halides and oligomerization of enone under reductive conditions, and isomerization of the desired product to conjugated enone. In this work, we demonstrate the Ni-catalyzed intermolecular cross-dialkylation of alkynes without organometallic reagents. This mild method allows for the regio- and stereo-selective conversion of both terminal and internal alkynes into tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes with up to four aliphatic substituents in the absence of any directing group.

Fig. 1. Stereodefined access to multiple alkylated alkenes.

a Ni-catalyzed intermolecular carbo-difunctionalization of alkyne. b Ni-catalyzed cross-alkyl-functionalization of alkyne via cyclometalation. c Ni-catalyzed stereodefined intermolecular dialkylation of alkyne.

Results

Reaction optimization

With these concerns in mind, we set out to examine the hypothesis using 1-hexyne (1a), 2-cyclohexen-1-one (2a) and 1-bromobutane (3a) as prototype substrates (Table 1). After extensive evaluation of a series of reaction parameters, we identified the use of NiBr2·DME (10 mol%), 4-cyanopyridine (5 mol%, A1), cerium chloride (0.8 equiv), potassium iodide (2.0 equiv), zinc (4.5 equiv) in the presence of water (1.5 equiv) in N,N-dimethylformamide (0.1 M) at room temperature as the optimal conditions, affording the desired three-component sequential dialkylation product 4a in 66% yield (Table 1, entry 1). The reaction demonstrated exclusive regio- and syn-selectivity, which is complementary to the regio- and stereo-selectivity of Ni-catalyzed radical addition pathway. Similar result was obtained when presynthesized precatalyst was used, giving the desired product 4a in 64% yield. The reaction showed lower efficiency in the absence of A1, affording 4a in 37% yield (Table 1, entry 2). Increasing the loading of A1 to 10 mol% and 20 mol% did not further improve the yield of 4a (Table 1, entries 3 and 4). Replacing A1 with pentafluoropyridine (A2) gave trialkylated alkene 4a in 34% yield (Table 1, entry 5). The use of other nickel catalyst precursors, such as NiBr2, NiCl2·DME, and Ni(COD)2, led to inferior results (Table 1, entries 6–8). No desired product was detected in the absence of nickel catalyst or sacrificial reductant zinc (Table 1, entry 9). The presence of cerium chloride and potassium iodide are both crucial for the three-component reaction, trace amount of desired product was formed without either additive (Table 1, entry 10). The role of KI is likely to undergo halide exchange to generate alkyl iodide in situ slowly from alkyl bromide to maintain alkyl iodide in low concentration during the reaction course. Other Lewis acids proved to be unsuccessful in this reaction (Table 1, entry 11). Water plays a critical role as a mediator in this reaction, giving the optimal result with 1.5 equiv of water (Table 1, entries 12 and 13). Evaluation of solvent effect revealed that polar solvent is required for this reaction. The reaction delivered 4a in 23% and 43% yields, respectively, when the reaction was conducted in NMP or DMA (Table 1, entries 14 and 15).

Table 1.

Condition evaluation for the fully intermolecular cross-electrophile dialkylation of alkynes.

| Entry | Variation from “standard conditions”a | Yield of 4ab(%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 66 (64), 64c |

| 2 | w/o A1 | 37 |

| 3 | A1 (10 mol%) | 62 |

| 4 | A1 (20 mol%) | 59 |

| 5 | A2 instead of A1 | 34 |

| 6 | NiCl2·DME instead of NiBr2·DME | 55 |

| 7 | NiBr2 instead of NiBr2·DME | 45 |

| 8 | Ni(COD)2 instead of NiBr2·DME | 36 |

| 9 | w/o “Ni” or Zn | NR |

| 10 | w/o CeCl3 or KI | Trace |

| 11 | ZnBr2/ZnCl2/TMSCl instead of CeCl3 | Trace |

| 12 | w/o H2O | 17 |

| 13 | H2O (2 equiv) | 51 |

| 14 | NMP instead of DMF | 23 |

| 15 | DMA instead of DMF | 43 |

aReaction was run using 0.4 mmol of 1a, 0.2 mmol of 2a, and 0.4 mmol of 3a under indicated conditions for 48 h.

bYield was determined by GC analysis using n-dodecane as internal standard. Isolated yield is shown in the parentheses. A1 = 4-cyanopyridine, A2 = pentafluoropyridine.

cNiBr2·DME and A1 were presynthesized as the catalyst.

Substrate scope

With the optimized conditions in hand, we turned to examine the scope of this transformation. To our delight, this reaction protocol is applicable to a wide variety of functionalized alkynes, alkyl bromides, and enones, furnishing various advanced tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes with multiple aliphatic substituents in excellent levels of regio-, chemo-, and stereo-selectivity (Figs. 2 and 3). First, the scope of alkynes was investigated under the reaction conditions (Fig. 2). Aliphatic terminal alkynes with varied lengths of carbon chain gave corresponding trialkyl substituted alkenes in good yields (4a-4c). Aliphatic alkynes tethered with chloride, ester, amides are tolerated in this method, furnishing corresponding functionalized alkenes in synthetic useful yields, rendering further elaboration opportunities for the products (4d-4h). The reaction could be applied to late-stage functionalization of natural products and drug molecules. Estrone and oxaprozin derived terminal alkynes could be transformed to corresponding trialkylated products in 52% and 57% yields, respectively (4i and 4j). Notably, the reaction conditions could be applied to gram-scale synthesis (10.0 mmol scale) without erasing the efficiency of the reaction, affording 1.68 g of 4a in 67% yield. Second, terminal aromatic alkynes were tested. Electron-donating and electron-withdrawing substituted aryl alkynes are all good substrates for this transformation with A2 (20 mol%) and zinc bromide (10 mol%) as Lewis acid. In these cases, 2-methyl-2-butanol was used as proton source instead of water. Terminal aryl alkynes with para-, meta-, and ortho-substitution patterns could be converted to corresponding alkenes with two aliphatic substituents in moderate to good yields (5a-5k). It is noteworthy that alkynyl arylhalides are compatible in this reaction with halides intact (5f and 5g), leaving a chemical handle to build molecular complexity by cross-coupling reactions. The structure and stereochemistry of the product were determined unambiguously by X-ray diffraction analysis of 5c. Alkynyl indole could be converted to substituted vinyl indole in synthetic useful yield (5l). Third, internal alkynes were also examined, which could lead to synthetically challenging tetrasubstituted alkenes. Internal alkynes are challenging substrates for Ni-catalyzed carbo-difunctionalization of alkynes due to their steric hindrance. It is noteworthy that internal alkynes are compatible in this reaction. Diverse substituted 1-phenyl-2-alkylalkynes are good substrates under the reaction conditions, giving trialkylaryl-substituted alkenes (6a-6e) in good yields with excellent regioselectivities. The regio- and stereochemistry was confirmed by X-ray diffraction analysis of 6b. Stereodefined alkenes with four aliphatic substitutents could be obtained using this protocol in good yields with exclusive regio- and stereo-selectivity (6f-6i).

Fig. 2. Scope for the syn-cross-electrophile dialkylation of alkynes with respect to alkynes.

Unless otherwise noted, isolated yield is shown on 0.2 mmol scale under standard conditions. See Table 1, entry 1 for detail. aIsolated yield on 10.0 mmol scale. bNiBr2·DME (10 mol%), A2 (20 mol%), Zn (2.5 equiv), KI (2.0 equiv), ZnBr2 (10 mol%), 2-methyl-2-butanol (2.0 equiv), DMF (0.1 M), rt, overnight. cAlkyne was added in two portions. 1.0 equiv alkyne was added after 5 h. dAlkyne was added in two portions. 1.0 equiv alkyne was added after 3 h. eAlkyne (2.0 equiv), enone (0.2 mmol), alkyl bromide (3.5 equiv), NiBr2·DME (10 mol%), Zn (5.0 equiv), CsI (5.0 equiv), ZnI2 (30 mol%), 2-methyl-2-butanol (3.0 equiv), DMF (0.05 M) and 1.0 equiv alkyne was added after 3 h, rt, overnight.

Fig. 3. Scope for the syn-cross-electrophile dialkylation of alkynes with respect to alkyl eletrophiles.

Unless otherwise noted, isolated yield is shown on 0.2 mmol scale under standard conditions. See Table 1, entry 1 for detail. aNiBr2·DME (10 mol%), A2 (20 mol%), Zn (2.5 equiv), KI (2.0 equiv), ZnBr2 (10 mol%), 2-methyl-2-butanol (2.0 equiv), DMF (0.1 M), rt, overnight. bThe reaction was conducted using 0.2 mmol of enone (1.0 equiv), alkyne (2.8 equiv), n-BuBr (3.5 equiv) in the presence of NiBr2·DME (10 mol%), Zn (3.0 equiv), CsI (5.0 equiv), 2-methyl-2-butanol (2.0 equiv), and ZnI2 (30 mol%) in DMF (0.05 M). cStandard conditions were used. dAlkyne was added in two potions. 1.0 equiv of alkyne was added after 5 h. eAlkyne was added in two portions. 1.0 equiv of alkyne was added after 3 h. fYield based on the recovery of enone.

Next, we evaluated the scope of two electrophiles (Fig. 3). A wide variety of alkyl bromides proved amenable to this reaction, substantially expanding the synthetic potential of this protocol (Fig. 3, top). Alkyl bromides with different lengths of aliphatic chain as well as alkyl or aryl ethers, chlorides, could be combined with terminal and internal alkynes, affording tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes in moderate to good yields (7a-7l). Notably, the reaction demonstrated excellent selectivity over alkynes and alkenes. Alkene or alkyne tethered alkyl bromides underwent cross-electrophile three-component reaction smoothly, delivering corresponding multiple substituted alkenes in 68% and 65% yields, respectively, leaving the double bond and triple bond intact (7m and 7n). Moreover, functional groups, such as ester and amide, which are sensitive to organometallic reagents, could be tolerated under the reaction conditions (7o-7r).

Secondary alkyl halides, such as 4-iodotetrahydro-2H-pyran, could be converted to corresponding alkene 7s in 52% yield. Unfortunately, tertiary alkyl halides could not form the desired product. Additionally, various cyclic and acyclic enones could be involved in this cross-electrophilile dialkylation process (Fig. 3, bottom). Cycloheptenone could be coupled with alkyne and n-butylbromide to give 8a in 61% yield. A couple of acyclic enones were also good substrates in this three-component reaction, furnishing corresponding multialkylated alkenes with regio- and stereocontrol in 53%-61% yields (8b-8e). Cyclohexenones with diverse bulky substitutions were also tolerated in the reaction, delivering the desired products (8f and 8g) in 52% and 66% yields, respectively. Acyclic enones with more steric hindered substituents and acryamides could be involved in the reaction, albeit in lower effeciency (8h and 8i). The major competing side reactions include the alkylalkynylation (8h′)and hydroalkylation of alkynes (8i′) (Supplementary Figs. 11–18).

Derivatization

Unfunctionalized alkenes with multiple substitutions are important yet difficult to access13. The resulting alkenes could be transformed into unfunctionalized alkenes by removing the carbonyl group in good yields (9a-9f), providing a useful method to tri- and tetrasubstituted all-carbon alkenes without any functional group (Fig. 4). Notably, this protocol provides a convenient access to unsymmetrical all-carbon substituted alkenes with up to four aliphatic substituents in a regio- and stereocontrolled fashion, which are inaccessible otherwise.

Fig. 4. Synthesis of unfunctionalized tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes.

These results indicate that product of dialkylation of alkynes can be sufficiently transformed into unfunctionalized alkenes. Yields are for isolated and purified products. The detailed procedures have been presented in Supplementary Information (SI).

To further demonstrate the utility of this methodology, an array of synthetic applications of the products were performed based on 4a (Fig. 5). By reductive amination or reduction of the carbonyl group, 4a could be converted to homoallyic amine (10) and alcohol (11) in 58% and 90% yields, respectively. Skipped diene 12 was obtained in 76% yield by Wittig reaction. Epoxidation of the double bond furnished 13 in 60% yield using m-CPBA as the oxidant. The product could undergo site-selective desaturation to give unconjugated dienone 14 in 70% yield. Treating 4a under oxidative conditions underwent aromatization to deliver vinyl free phenol 15 in 61% yield.

Fig. 5. Synthetic applications of 4a.

Reaction conditions: a Reductive amination. (1) PhNH2, MgSO4, AcOH, DCM (0.2 M), rt, 2 h; (2) NaBH3CN, MeOH, rt, 10 h. b Reduction. NaBH4, MeOH, rt, 2 h. c Wittig Olefination. n-BuLi, Ph3PCH2Br, THF, −30 °C to rt, overnight. d Epoxidation. m-CPBA, NaHCO3, DCM, 0 °C, 2 h. e Desaturation. Pd(TFA)2, 1 atm O2, DMSO, 85 °C, 14 h. f Aromatization. Pd(TFA)2, PTSA, N,N-dimethylpyridin-2-amine, 1 atm O2, DMSO, 80 °C, 24 h.

Mechanistic consideration

To shed light on the detail of this sequential three-componet reaction, we set up a series of experiments to probe the reaction mechanism (Fig. 6). First, 1-phenyl-1-propyne was exposed to the reaction conditions in the presence of D2O (4 equiv) in lieu of H2O, 6a-d was obtained in 72% yield with 96% deuteration of single proton at α-postion to carbonyl as a mixture of diastereomers. While no deuterium incorpoartion was observed when 6a was subjected to the reaction conditions in the presence of deuterated water. When deuterated phenylacetylene was subjected to the reaction conditions, 5a-d was obtained in 42% yield. No deuterium scrambling from terminal position of phenylacetylene to α-postion to carbonyl was observed. These results indicate one α-proton of ketone is from water during the reaction course and non-exchangable with surroundings. Next, radical clock experiments were carried out. When (bromomethyl)cyclopropane was used in the reaction, skipped dienone 16 was obtained in 58% yield by ring-opening/cross-coupling reaction process without the formation of 16′. Moreover, homoallylic bromide 17 could be transformed into 18 via radical cyclization/cross-coupling process in 16% yield along with the formation of byproducts 19 and 2057. The acyclic product 18′ was not detected. In addition, the use of TEMPO completely shut down the desired reaction. The formation of 21 and 22 were detected by mass. No n-butyl zinc species was detected during the reaction course (Supplementary Figs. 5–9). The combined results suggest the involvement of alkyl radical species in this reaction.

Fig. 6. Mechanistic investigations and control experiments.

a Reaction in the presence of deuterated water. b Treat the product 6a under reaction conditions with deuterated water. c The reaction of deuterated phenylacetylene. d Radical clock reaction using cylcopropylmethylbromide. e Radical clock reaction using 17. f Radical trap with TEMPO.

Proposed reaction mechanism

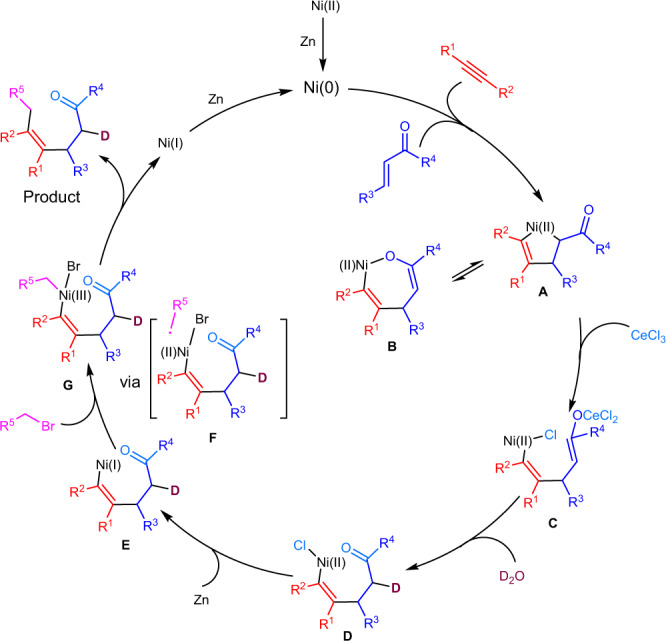

Based on the experimental results and literature, a proposed mechanism of this reaction is depicted in Fig. 7. First, Ni (0) species generated from Ni (II) by reduction initiated metallacyclic intermediate A via cross-oxidative cyclometallation between alkyne and enone. C-bound intermediate A could equilibriate with O-bound intermediate B. In the presence of Lewis acid (CeCl3 or ZnBr2), intermediate C was formed via transmetalation, which could further undergo protonation to give vinylnickel intermediate D with proton source. The presence of Lewis acid might faciliate the generation of C by forming M-O bond (M = Ce or Zn). D could be reduced by zinc to give Ni (I) intermediate E, which could undergo oxidative addition to alkyl bromide to form Ni (III) intermediate G via single stepwise electron transfer and radical recombination with F. Intermediate G underwent reductive elimination to form the final product along with Ni(I) intermediate, which could be further reduced by Zn to complete the catalytic cycle.

Fig. 7. Proposed reaction mechanism.

Specifically, A, B: Ni (II) intermediates of cyclometallation of alkynes with enones; C, D: Ni (II) intermediates after Ni-O bond dissociation; E: Ni (I) intermediate reduced by Zn; F: transition state for single-electron reduction of Ni (I) with alkyl bromides; G: Ni (III) intermediate of oxidative addition to alkyl bromides.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated a Ni-catalyzed fully intermolecuar regio- and stereo-selective cross-dialkylation of alkynes in the presence of alkyl halides and α,β-unsaturated compounds, affording stereodefined tri- and tetrasubstituted alkenes with multiple alkyl substitutions58–62. Notably, the reaction enables syn-selective dialkylation of alkynes with exclusive regioselectivity in the absence of any direction group, providing an alternative to access multi-substituted unfunctionalized alkenes from readily-accessible reagents. The use of reductive conditions allows for the reaction proceed at room temperature, circumventing the use of air- and moisture-sensitive organometallic reagents.

Methods

General procedure for the fully intermolecular dialkylation of alkynes

The reaction was operated in a nitrogen-filled glove box. 4-Cyanopyridine (5 mol%), zinc (4.5 equiv), CeCl3 (0.8 equiv), KI (2.0 equiv), NiBr2·DME (10 mol%), alkyne (2.0 equiv, if solid), and alkyl bromide (2.0 equiv, if solid) were added into an oven-dried vial containing a magnetic stirring bar. If the alkyne or alkyl bromide is a solid, it was added along with other solid reagents. Anhydrous DMF (0.1 M) was added and rapid stirring was commenced. Then H2O (1.5 equiv), alkyne (2.0 equiv, if liquid), enone (0.2 mmol), and alkyl bromide (2.0 equiv, if liquid) were added sequentially via syringe. The vial was sealed with parafilm and stirred vigorously for 48 h. The reaction was diluted with ethyl acetate (30 mL) and washed with brine (50 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted twice with ethyl acetate (20 mL). The combined organic layer was dried over magnesium sulfate, filtered, evaporated and purified by silica gel chromatography with hexanes/ethyl acetate as eluent to give the corresponding product in pure form.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

We sincerely acknowledge NSFC (21971101 and 21801126), Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation (2019A1515011976), Thousand Talents Program for Young Scholars, The Pearl River Talent Recruitment Program (2019QN01Y261), and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Catalysis (No. 2020B121201002) for financial support. We thank Dr. Xiaoyong Chang (SUSTech) for X-ray crystallographic analysis. We acknowledge the assistance of SUSTech Core Research Facilities, and Shan Wang (SUSTech) for reproducing the results of 4e, 5h, 6h, and 7j.

Author contributions

Y.Z.Z. discovered and developed the reaction. W.S. conceived and designed the project. Y.Z.Z. and N.X. performed the experiments and collected the data. W.S. wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors.

Data availability

The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files, and also are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers of CCDC 1983359 and CCDC 1983360. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Peer review information Nature Communications thanks Magnus Rueping, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21083-w.

References

- 1.Bhatt U, Christmann M, Quitschalle M, Claus E, Kalesse M. The first total synthesis of (+)-ratjadone. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:1885–1893. doi: 10.1021/jo005768g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith AB, III, Qiu Y, Jones DR, Kobayashi K. Total synthesis of (-)-discodermolide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:12011–12012. doi: 10.1021/ja00153a030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.White JD, Carter RG, Sundermann KF, Wartmann M. Total synthesis of Epothilone B, Epothilone D, and cis- and trans-9, 10-dehydroepothilone D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5407–5413. doi: 10.1021/ja010454b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harper MJK, Walpole AL. Contrasting endocrine activities of cis and trans isomers in a series of substituted triphenylethylenes. Nature. 1966;212:87–87. doi: 10.1038/212087a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan VC. Antiestrogens and selective estrogen receptor modulators as multifunctional medicines. 2. Clinical considerations and new agents. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:1081–1111. doi: 10.1021/jm020450x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nemoto H, Shiraki M, Nagamochi M, Fukumoto K. A concise enantiocontrolled total synthesis of (-)-α-Bisabolol and (+)-4-epi-α-Bisabolol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1993;34:4939–4942. doi: 10.1016/S0040-4039(00)74051-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Takahashi A, Kirio Y, Sodeoka M, Sasai H, Shibasaki M. Highly stereoselective synthesis of exocyclic tetrasubstituted enol ethers and olefins. A synthesis of nileprost. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:643–647. doi: 10.1021/ja00184a036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itami K, Yoshida J-I. Multisubstituted olefins: platform synthesis and applications to materials science and pharmaceutical chemistry. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2006;79:811–824. doi: 10.1246/bcsj.79.811. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Döbler C, Mehltretter GM, Sundermeier U, Beller M. Osmium-catalyzed dihydroxylation of olefins using dioxygen or air as the terminal oxidant. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10289–10297. doi: 10.1021/ja000802u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Etayo P, Vidal-Ferran A. Rhodium-catalysed asymmetric hydrogenation as a valuable synthetic tool for the preparation of chiral drugs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2013;42:728–754. doi: 10.1039/C2CS35410A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Catalytic asymmetric dihydroxylation. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2483–2547. doi: 10.1021/cr00032a009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Verendel JJ, Pamies O, Dieguez M, Andersson PG. Asymmetric hydrogenation of olefins using chiral crabtree-type catalysts: scope and limitations. Chem. Rev. 2014;114:2130–2169. doi: 10.1021/cr400037u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flynn AB, Ogilvie WW. Stereocontrolled synthesis of tetrasubstituted olefins. Chem. Rev. 2007;107:4698–4745. doi: 10.1021/cr050051k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Negishi E-I, et al. Recent advances in efficient and selective synthesis of di-, tri-, and tetrasubstituted alkenes via pd-catalyzed alkenylation-carbonyl olefination synergy. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008;41:1474–1485. doi: 10.1021/ar800038e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deng H, Fan X, Chen Z, Xu Q, Wu J. Photoinduced nickel-catalyzed chemo- and regioselective hydroalkylation of internal alkynes with ether and amide α-hetero C(sp3)-H bonds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:13579–13584. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b08158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatterjee AK, Choi T-L, Sanders DP, Grubbs RH. A general model for selectivity in olefin cross metathesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:11360–11370. doi: 10.1021/ja0214882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoveyda AH, Zhugralin AR. The remarkable metal-catalysed olefin metathesis reaction. Nature. 2007;450:243–251. doi: 10.1038/nature06351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker MR, Watson RB, Schindler CS. Beyond olefins: new metathesis directions for synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018;47:7867–7881. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00391B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terao J, Bando F, Kambe N. Ni-catalyzed regioselective three-component coupling of alkyl halides, arylalkynes, or enynes with R-M (M = MgX’, ZnX’) Chem. Commun. 2009;45:7336–7338. doi: 10.1039/b918548h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, García-Domínguez A, Nevado C. Nickel-catalyzed stereoselective dicarbofunctionalization of alkynes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:6938–6941. doi: 10.1002/anie.201601296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guo L, Song F, Zhu S, Li H, Chu L. syn-selective alkylarylation of terminal alkynes via the combination of photoredox and nickel catalysis. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4543. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06904-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xue F, Zhao J, Hor TSA. Ambient arylmagnesiation of alkynes catalysed by ligandless nickel (II) Chem. Commun. 2013;49:10121–10123. doi: 10.1039/c3cc45202f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xue F, Zhao J, Hor TSA, Hayashi T. Nickel-catalyzed three-component domino reactions of aryl grignard reagents, alkynes, and aryl halides producing tetrasubstituted alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:3189–3192. doi: 10.1021/ja513166w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yada A, Yukawa T, Nakao Y, Hiyama T. Nickel/AlMe2Cl-catalysed carbocyanation of alkynes using arylacetonitriles. Chem. Commun. 2009;45:3931–3933. doi: 10.1039/b907290j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakao Y, et al. Allylcyanation of alkynes: regio- and stereoselective access to functionalized di- or trisubstituted acrylonitriles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7116–7117. doi: 10.1021/ja060519g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakao Y, Yada A, Ebata S, Hiyama T. A dramatic effect of lewis-acid catalysts on nickel-catalyzed carbocyanation of alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:2428–2429. doi: 10.1021/ja067364x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakao Y, Yada A, Hiyama T. Heteroatom-directed alkylcyanation of alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10024–10026. doi: 10.1021/ja1017078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Babu MH, Kumar GR, Kant R, Reddy MS. Ni-catalyzed regio- and stereoselective addition of arylboronic acids to terminal alkynes with a directing group tether. Chem. Commun. 2017;53:3894–3897. doi: 10.1039/C6CC10256E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yue H, Zhu C, Kancherla R, Liu F, Rueping M. Regioselective hydroalkylation and arylalkylation of alkynes by photoredox/nickel dual catalysis: application and mechanism. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:5738–5746. doi: 10.1002/anie.201914061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu C, et al. A multicomponent synthesis of stereodefined olefins via nickel catalysis and single electron/triplet energy transfer. Nat. Catal. 2019;2:678–687. doi: 10.1038/s41929-019-0311-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu C, Yue H, Chu L, Rueping M. Recent advances in photoredox and nickel dual catalyzed cascade reactions: pushing the boundaries of complexity. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:4051–4064. doi: 10.1039/D0SC00712A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amarasinghe KKD, Chowdhury SK, Heeg MJ, Montgomery J. Structure of an η1 Nickel O-Enolate: mechanistic implications in catalytic enyne cyclizations. Organometallics. 2001;20:370–372. doi: 10.1021/om0010013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hratchian HP, et al. Combined experimental and computational investigation of the mechanism of nickel-catalyzed three-component addition processes. Organometallics. 2004;23:4636–4646. doi: 10.1021/om049471a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montgomery J. Nickel-catalyzed cyclizations, couplings, and cycloadditions involving three reactive components. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:467–473. doi: 10.1021/ar990095d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montgomery J. Nickel-catalyzed reductive cyclizations and couplings. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3890–3908. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Montgomery J, Oblinger E, Savchenko AV. Nickel-catalyzed organozinc-promoted carbocyclizations of electron-deficient alkenes with tethered unsaturation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:4911–4920. doi: 10.1021/ja9702125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montgomery J, Savchenko AV. Nickel-catalyzed cyclizations of alkynyl enones with concomitant stereoselective tri-or tetrasubstituted alkene introduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2099–2100. doi: 10.1021/ja952026+. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Montgomery J, Seo J, Chui HMP. Competition between insertion and conjugate addition in nickel-catalyzed couplings of enones with unsaturated functional groups. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:6839–6842. doi: 10.1016/0040-4039(96)01528-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oblinger E, Montgomery J. A new stereoselective method for the preparation of allylic alcohols. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:9065–9066. doi: 10.1021/ja9719182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ni Y, Amarasinghe KKD, Montgomery J. Nickel-catalyzed cyclizations and couplings with vinylzirconium reagents. Org. Lett. 2002;4:1743–1745. doi: 10.1021/ol025812+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel SJ, Jamison TF. Catalytic three-component coupling of alkynes, imines, and organoboron reagents. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:1364–1367. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patel SJ, Jamison TF. Asymmetric catalytic coupling of organoboranes, alkynes, and imines with a removable (trialkylsilyloxy) ethyl group-direct access to enantiomerically pure primary allylic amines. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:3941–3944. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikeda S-I. Nickel-catalyzed intermolecular domino reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2000;33:511–519. doi: 10.1021/ar9901016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawashima T, Ohashi M, Ogoshi S. Nickel-catalyzed formation of 1, 3-dienes via a highly selective cross-tetramerization of tetrafluoroethylene, styrenes, alkynes, and ethylene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:17795–17798. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kawashima T, Ohashi M, Ogoshi S. Selective catalytic formation of cross-tetramers from tetrafluoroethylene, ethylene, alkynes, and aldehydes via nickelacycles as key reaction intermediates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:17423–17427. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b11671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nie M, Fu W, Cao Z, Tang W. Enantioselective nickel-catalyzed alkylative alkyne-aldehyde cross-couplings. Org. Chem. Front. 2015;2:1322–1325. doi: 10.1039/C5QO00148J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ogoshi S, Arai T, Ohashi M, Kurosawa H. Nickeladihydrofuran. Key intermediate for nickel-catalyzed reaction of alkyne and aldehyde. Chem. Commun. 2008;44:1347–1349. doi: 10.1039/b717261c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang Y, Zhu S-F, Zhou C-Y, Zhou Q-L. Nickel-catalyzed enantioselective alkylative coupling of alkynes and aldehydes: synthesis of chiral allylic alcohols with tetrasubstituted olefins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:14052–14053. doi: 10.1021/ja805296k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shimkin KW, Montgomery J. Synthesis of tetrasubstituted alkenes by tandem metallacycle formation/cross-electrophile coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:7074–7078. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b04637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herath A, Li W, Montgomery J. Fully intermolecular nickel-catalyzed three-component couplings via internal redox. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:469–471. doi: 10.1021/ja0781846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herath A, Montgomery J. Highly chemoselective and stereoselective synthesis of Z-enol silanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:8132–8133. doi: 10.1021/ja802844v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Herath A, Thompson BB, Montgomery J. Catalytic intermolecular reductive coupling of enones and alkynes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:8712–8713. doi: 10.1021/ja073300q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Huang W-S, Chan J, Jamison TF. Highly selective catalytic intermolecular reductive coupling of alkynes and aldehydes. Org. Lett. 2000;2:4221–4223. doi: 10.1021/ol006781q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Li W, Herath A, Montgomery J. Evolution of efficient strategies for enone-alkyne and enal-alkyne reductive couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:17024–17029. doi: 10.1021/ja9083607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li W, Montgomery J. Ligand-guided pathway selection in nickel-catalyzed couplings of enals and alkynes. Chem. Commun. 2012;48:1114–1116. doi: 10.1039/C2CC17073F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phillips JH, Montgomery J. Mechanistic insights into nickel-catalyzed cycloisomerizations. Org. Lett. 2010;12:4556–4559. doi: 10.1021/ol101852w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beckwith ALJ, Easton CJ, Lawrence T, Serelis AK. Reactions of methyl-substituted hex-5-enyl and pent-4-enyl radicals. Aust. J. Chem. 1983;36:545–556. doi: 10.1071/CH9830545. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang J, Dong Z, Yang C, Dong G. Modular and regioselective synthesis of all-carbon tetrasubstituted olefins enabled by an alkenyl Catellani reaction. Nat. Chem. 2019;11:1106–1112. doi: 10.1038/s41557-019-0358-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wu Z, Fatuzzo N, Dong G. Distal alkenyl C−H functionalization via the palladium/norbornene cooperative catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:2715–2720. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b11479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cheng L, et al. Nickel-catalyzed hydroalkylation and hydroalkenylation of 1,3-dienes with hydrazones. Chem. Sci. 2019;10:10417–10421. doi: 10.1039/C9SC04177J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lv L, Zhu D, Qiu Z, Li J, Li C-J. Nickel-catalyzed regioselective hydrobenzylation of 1,3-dienes with hydrazones. ACS Catal. 2019;9:9199–9205. doi: 10.1021/acscatal.9b02483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lv L, Yu L, Qiu Z, Li C-J. Switch in selectivity for formal hydroalkylation of 1,3-dienes and enynes with simple hydrazones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020;59:6466–6472. doi: 10.1002/anie.201915875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all other data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and Supplementary Information files, and also are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers of CCDC 1983359 and CCDC 1983360. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.