Abstract

Background:

Effective weight-management interventions require frequent interactions with specialized multidisciplinary teams of medical, nutritional, and behavioral experts to enact behavioral change. However, barriers that exist in rural areas, such as transportation and a lack of specialized services, can prevent patients from receiving quality care.

Methods:

We recruited patients from the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Weight & Wellness Center into a 1single-arm, non-randomized study of a remotely delivered 16-week evidence-based healthy lifestyle program. Every four weeks, participants completed surveys that included their willingness to pay for services like those experienced in the intervention. A two-item Willingness-to-Pay survey was administered to participants asking about their willingness to trade their face-to-face visits for videoconference visits based on commute and co-pay.

Results:

Overall, those with a travel duration of 31–45 minutes had a greater willingness to trade in-person visits for telehealth than any other group. Participants who had a travel duration less than 15 minutes, 16–30 minutes, and 46–60 minutes experienced a positive trend in willingness to have telehealth visits until week 8, where there was a general negative trend in willingness to trade in-person visits for virtual. Participants believed that telemedicine was useful and helpful.

Conclusions:

In rural areas where patients travel 30–45 minutes a telemedicine-delivered, intensive weight-loss intervention may be a well-received and cost-effective way for both patients and the clinical care team to connect.

Introduction

Obesity is a costly and preventable disease that affects 42.4% of Americans2 with a significantly higher prevalence among adults living in rural counties3. Effective weight-management interventions require frequent interactions with specialized multidisciplinary teams of medical, nutritional and behavioral experts to enact behavioral change4, however; this becomes difficult in rural areas as barriers, such as transportation and a lack of specialized services5, can prevent patients from receiving quality care. High direct and indirect costs for the patient and system can arise from these travel burdens. Intangible opportunity costs include a patient’s travel time to specialized clinics, in addition to direct costs of gas, and lost wages from taking time off. Telemedicine, two-way live videoconferencing, has the potential to reduce these costs for rural patients, and mobile healthcare (mHealth) has the potential to enact behavioral change and impact patient, provider, and community engagement through bi-directional feedback.

Current literature on telemedicine is sparse with the majority of studies looking at the feasibility of remote healthcare. To our knowledge, few trials have explored the patient’s willingness to pay for telemedicine and even fewer have explored willingness to pay in the context of rural obesity management. Outside of rural obesity management, the current literature offers a favorable outlook on paying for telemedicine. A German study attempted to determine who is more likely to undergo online treatment and found willingness to pay for telemedicine is partly influenced by monthly net income and education level6. Another study found that patients with a history of psoriasis or melanoma were willing to pay a median out-of-pocket cost of 25 dollars for a telehealth visit if it meant faster access to dermatological care7. Lastly, a study attempting to quantify consumer demand indicated representative United States households were willing to pay between 4 and 7 dollars per month for the ability to receive diagnosis, treatment, monitoring and consultations remotely with patients living more than 20 miles away willing to pay a greater amount for telecare8. The purpose of this manuscript is to present preliminary findings on how willing rural adult patients are to pay for remote healthcare delivery in a weight-management program.

Methods

Study design and setting

A single-arm, non-randomized pilot study enrolled participants attending the Dartmouth-Hitchcock (D-H) Weight and Wellness Center between November 2017 and September 2018. D-H is a 396-bed hospital located in Lebanon, NH, on the New Hampshire and Vermont border in Grafton County, serving over 1.5 million persons in the region. According to the 2010 census, the region’s classification was rural, with 65 percent of persons living in a health professional shortage or medically underserved area9. The Weight & Wellness Center was established in 2016 and during this study period, evaluated 385 new consultations for adult obesity management, staffed by three physicians, an advanced practice registered nurse, a behavioral psychologist, a registered nurse exercise specialist, two health coaches, two registered dietitians, and administrative staff. The Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at Dartmouth College approved the study, and the clinical trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03309787).

Intervention description

The Healthy Lifestyle Program consisted of a 16-week curriculum based on the Diabetes Prevention Program that focused on health-behavior change (mindfulness, movement, problem-solving, and nutrition) delivered by a health coach, registered dietitian, and nurse exercise specialist which has previously been described1. Patients are referred from their primary care providers and complete an initial comprehensive multidisciplinary intake form before entering the program, and have the option of 1:1 or group (up to 15–20) visits for weekly coaching appointments. For this study, participants had the opportunity, after their initial evaluation, to complete 30-minute, individual, 1:1 remote coaching visits via telemedicine in place of in-person care. Patients who did not consent to the study received regular clinical care while every patient who consented to be in the study received the intervention treatment. The structure of the remote program paralleled on-site routine care. Participants who consented to the study also wore a fitness device, either a Dartmouth College designed Amulet10, a Fitbit (San Francisco, CA), or both to track their physical activity. These wearables were embedded as part of a separate research study.

Telemedicine delivery

The D-H Center for Telehealth has an extensive infrastructure to support clinical initiatives within D-H and provided logistical and technical support for this project. All staff participated in on-site training sessions to ensure familiarity with the telehealth platform. Live, mock sessions, and ongoing on-site support were provided by the research assistant (RA) and by a Center for Telehealth staff. All communications came through a HIPAA-compliant Vidyo software. Coaching sessions took place in a private clinical area. An encrypted Samsung Galaxy Tab A 10.1 tablet, given to each participant for the home-based intervention with the same software, allowed them to interact with study personnel.

Study Procedures

Selection criteria and study procedures were previously described1. New patients were approached by the treating clinician and introduced to the study. If interested, the research assistant provided additional information and obtained informed consent. On-site objective assessments which included a 6-minute walk test, 30-second sit-to-stand test, grip strength test and a bioelectrical impedance analysis scan, all of which occurred at baseline and at 16 weeks. Subjective assessments began 4 weeks into the study and occurred in 4-week intervals until week 16. A two-item Willingness-to-Pay survey asked participants about their willingness to trade their face-to-face visits for videoconference visits based on commute time and co-pay. The first question asked participants at what point they would trade face-to-face visits for specified commute times (options included 0–15 minutes, 16–30 minutes, 31–45 minutes, 46–60 minutes and ≥60 minutes). The second item asked participants if they would be willing to engage in a telehealth visit with an upfront co-pay (options included $0–10, $11–20, $21–30, $31–40, $41–50, and ≥$50). Lastly, a 1:1 structured exit-interview conducted by the senior author at the end of the study gauged the participant’s impressions of the overall program and of the utility of telemedicine for a health coaching program. All received a $20 incentive at each in-person outcome assessment.

Statistical Analysis

We combined all data into a single dataset for analysis with continuous variables expressed as mean ± standard deviation and categorical as count (percent). Unpaired t-tests and chi-square tests assess differences between baseline and follow-up. Our primary outcome was willingness to pay assessed by the two questions listed above. The outcomes of these questions dichotomized at <30 minutes, and <$30, respectively. A repeated measures anova assessed the change of willingness to pay over time. We captured survey data using REDCap. All data were analyzed using STATA version 14 (College Station, TX). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Interview data were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed by a commercial transcription program and analyzed using Dedoose (Hermose Beach, CA). Topics were grouped and presented in aggregate.

Results

Overall, 27 participants completed the study with a mean age of 46.1±12.3 years (88.9% female). Participants indicated favorable satisfaction on a 1–5 Likert scale with higher scores indicating higher satisfaction with the program (4.7±0.48) and would recommend telemedicine visits to others using the same scale format (4.74±0.45). Table 1 presents data on potential opportunity costs from a patient perspective. Most participants spent half a day traveling to and from the medical center at both baseline (14 out of 27) and follow-up (17 out of 27) which was statistically significant (p=0.001). Individuals felt they spent more at follow-up, and more were willing to pay for a co-pay for telemedicine at follow up. For 41.5% of participants, they spent over $100 on travel costs, childcare, meals, and lost wages to visit their provider (p<0.001). At the end of 16 weeks, 69% reported that they would be willing to pay $30 or less for a telemedicine visit compared to 58% at baseline (p=0.003).

Table #1:

Patient Satisfaction and Willingness to Pay

| Question | Answers | Baseline | Follow-up | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| How much time, including travel, does it take from your day, to travel to Dartmouth-Hitchcock for an in-person visit with your provider? | Full day | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.9) | 0.001 |

| Half-day | 14 (45.2) | 17 (58.6) | ||

| Few hours | 8 (25.8) | 6 (20.7) | ||

| Minimal time | 7 (22.6) | 4 (13.8) | ||

| How much money might you spend on things like gas, meals, childcare, lost wages to travel to Dartmouth-Hitchcock for an in-person visit with your provider? | < $50 | 15 (48.3) | 14 (48.3) | <0.001 |

| $50–99 | 8 (25.8) | 3 (10.3) | ||

| $100–149 | 5 (16.1) | 10 (34.5) | ||

| $150–199 | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.5) | ||

| $200+ | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.5) | ||

| Would you be willing to pay a co-pay for a telemedicine appointment if not covered by insurance? | <$50 | 5 (16.1) | 3 (10.3) | 0.003 |

| <30 | 18 (58.1) | 20 (69.0) | ||

| No | 8 (28.8) | 6 (20.7) |

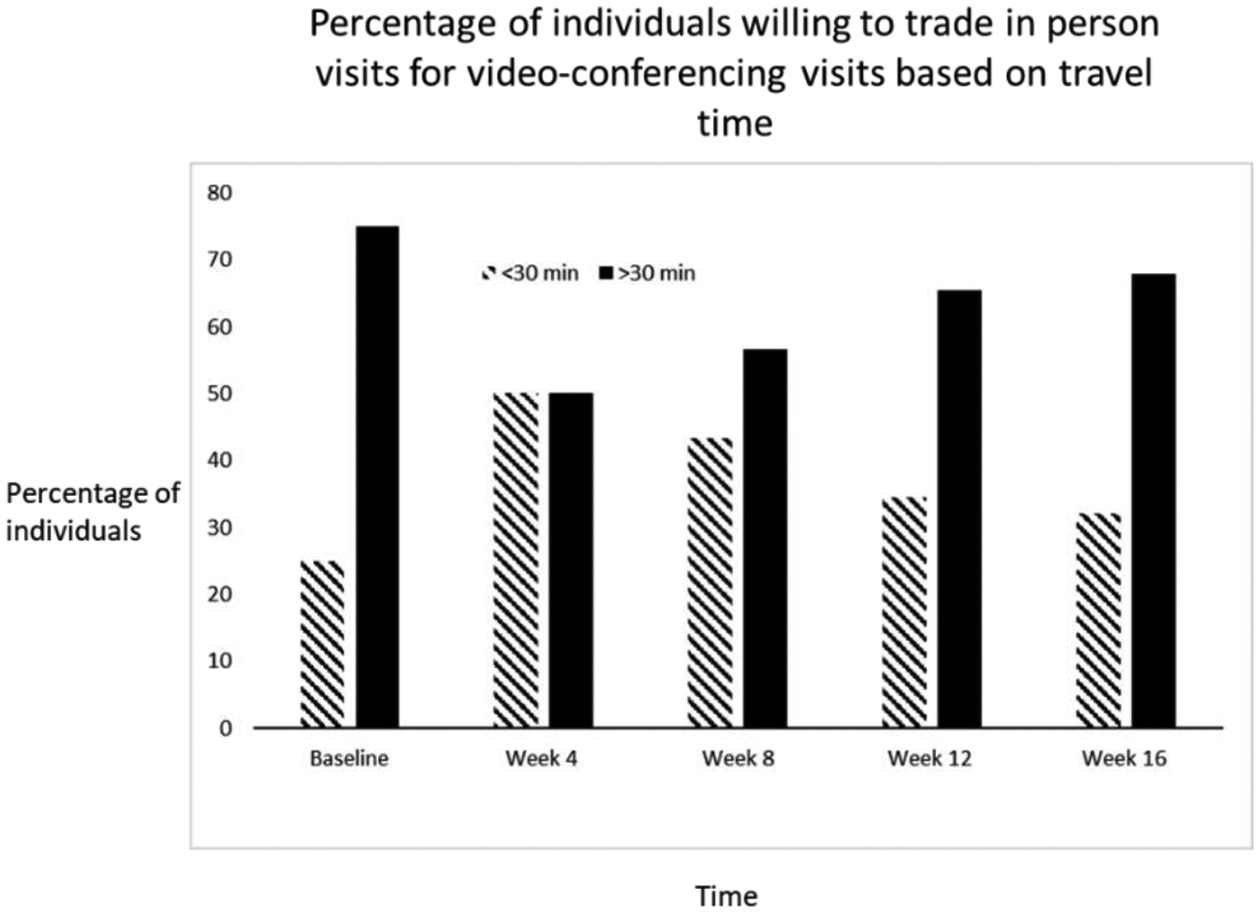

Figure 1 presents the trends of participants willing to trade their in-person visits for telemedicine visits throughout the study based on travel time. Those with a travel duration of 31–45 minutes had a greater willingness to trade in-person visits for telehealth than any other group. Participants who had a travel duration less than 15 minutes, 16–30 minutes, and 46–60 minutes experienced a positive trend in willingness to have telehealth visits until week 8, where there was a general negative trend in willingness to trade for in person visits (overall p=0.24). We present in Figure 2 that most were willing to consider telemedicine if their commute exceeded 30 minutes. The trends exhibited in Figure 2 were non-significant (p=0.15) over time. A co-pay that did not exceed $30 was more acceptable than a higher co-pay amount for participants. While there were trends over the 16-week intervention in their willingness to pay, they were non-significant (data not shown). We found no difference at baseline or follow-up as to whether miles from the medical center impacted one’s willingness to pay for a telemedicine visit.

Figure 1: Willingness to Pay for Telemedicine – Travel Time.

Figure 1 indicates how willing participants are to trade their in-person visits for remote visits based on different commute times over the duration of 16 weeks. Participants were asked at what point they would trade face-to-face visits for specified commute times (0–15min, 16–30min, 31–45 min, 46–60min, >60min)

Figure 2: Willingness to Trade In-Person for Telemedicine – Travel Time.

Figure 2 indicates the percentage of individuals who are willing to trade in-person visits for video conferencing based on travel time being greater than or less than 30 minutes over the duration of the 16 weeks. Participants were asked at what point they would trade face-to-face visits for specified commute times (<30min vs. >30min).

Table 2 describes select representative quotes from the exit interviews regarding the impact of telemedicine in this study. Participants generally believed that this modality was productive and helpful and that it led to reduced travel and expenses, flexibility, and cost-savings for their family and work.

Table 2:

Representative Quotes by Participants for Using Telemedicine

| Theme | Representative Quote |

|---|---|

| Flexibility (n=13) | You can be in your pajamas if you want to and do it [telemedicine] |

| Being able to be where I wanted to be or where I had to be. It made it work for me. You are not fighting traffic or rushing to get to an appointment. | |

| Cost Savings (n=10) | We are a one-income family. It puts a lot of pressure for me to make it work |

| It is nice it is at a cost I could afford | |

| Time Savings (n=19) | I did not need to take time off from work in the middle of the day to come in for an appointment |

| Not having to lose work time, family time, all of that | |

| Traveling (n=12) | The once a week drive up there [Dartmouth] plus the doctor’s appointment, I mean, that is a lot of driving. |

| It was nice to be able to be at home, not have to worry about driving an hour and a half to get here |

Counts in brackets indicate the number of respondents identifying such themes

Discussion

This study represents a unique assessment of patients’ willingness-to-pay for specialized obesity medicine care using a multidisciplinary team approach. Participants were highly satisfied with their telemedicine visits, and distance traveled to medical appointments had an impact on patients’ willingness-to-pay for such visits. These results suggest that this delivery modality may help overcome barriers to delivering the frequency and intensity necessary for obesity medicine in a rural population.

The current study provides preliminary but cautious support for the use of a remotely delivered intensive lifestyle program in a rural setting. Specifically, results highlighted that the duration of having to drive 31–45 minutes might be a ‘tipping point’ where patients may consider remote visits in place of in-person visits. The findings from in-person interviews indicate that the majority of the participants felt that the convenience and time-savings were beneficial. In rural areas, it is not uncommon to drive such distances, and access to public transportation is limited11. Delivering care via telemedicine not only reduces driving time for patients but also lessens work-related absences and travel-associated costs. Obesity is a chronic disease and requires long-term frequent communication between a patient and their care team for successful management12. A telemedicine design can foster frequent communication and provide such treatment. Future, adequately powered studies should evaluate the impact of telemedicine on these elements and in other rural settings.

Based on the results supporting distance trade-offs and how much patients are willing to spend for video-conferencing, the data suggest that clinics may be able to recoup costs. In fee-for-service environments, health coaches and nurses are currently unable to bill for their services in our model, while dietitians can bill if they fulfill Medicare criteria for locality13. Our results parallel others who have demonstrated patient participant willingness to pay for weight-loss interventions using technology14. For instance, Donelan14 found that at Massachusetts General Hospital, participants were willing to pay a co-pay of up to $50, mainly if they lived at a distance. This pay versus travel observation can also be seen in a study of participants using telemedicine with psoriasis or melanoma7. The observed cost participants would be willing to pay in our study was lower, and may reflect the different average socioeconomic status of patients residing in rural New Hampshire15. Our pilot results highlight that both distance and time spent traveling play critical roles in a patient’s willingness to pay.

The amounts observed with regard to willingness to pay for telehealth differ slightly than in other clinical arenas.8, 15 In southeast Nigeria, participants were willing to pay ~$2.04 per primary care visit,16 a price that is only affordable to families with higher socioeconomic standing. In Australia where healthcare is available to all citizens, participants indicated a willingness to pay up to $1.18 to change their visit from a general practitioner to a teledermoscopy visit, $43 for a dermatologist to review their results, and $117 to increase the chance of detecting melanoma if it was present17. Literature suggests that patients who are more willing to pay for telemedicine come from higher socioeconomic backrounds6, 8, 16. These findings are in contrast to participants facing various health issues that frequently travel to remote destinations. In this study, they would be willing to pay $50 to receive telecare while traveling15 for routine care, health advice while abroad, or medical support while on expeditions. These findings differ considerably from our own participants who were less likely to pay for a visit if the co-pay was $50.

While we were successful at gathering data throughout this study, a more prolonged study is likely needed to fully reflect a patient’s willingness-to-pay for telemedicine services. Such surveys are limited as they measure only what patient’s claim they would be willing to pay and are reliant on patient understanding of what they are currently paying for services. Estimated values might be more reflective of what they would like to pay for the service versus what they might actually pay. The sample size was small and without a control group; a larger randomized control trial could better answer the questions. Furthermore, the cohort was at risk for self-selection as they may have been willing to experiment with telemedicine over traditional in-person visits; hence, they may be more willing to pay for a telemedicine option than those who did not consent to our study. This, though, is in line with our pragmatic strategy of conducting a study within the clinical infrastructure. Strengths include acceptability and high satisfaction feedback from rural adult participants. Performing an economic analysis of telehealth for future studies is crucial in enabling the translation into both future practice and policy initiatives. As most participants spent over half the day traveling to and from medical appointments, more were willing at the study conclusion, to trade in person for telehealth visits. Importantly, these findings suggest that a rural population with obesity can be engaged and could potentially benefit financially from a telemedicine intervention, through time and gas saved without sacrificing program satisfaction.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that a telemedicine-based obesity management program demonstrates a high willingness-to-pay over in-person visits. Future studies should increase sample size and increase the intervention time to accurately gage patient’s willingness to pay over greater amount of time.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Center for Telehealth (Mary Lowry, Vanessa Brown, Fredric Glazer) for their assistance in developing the telemedicine component, and Tara Efstathiou, Laurie Gelb, Eugene Soboleski, Jane Brewer, Martha Catalona, Philip Oman, and Kaitlyn Christian, for their administrative assistance at the Weight and Wellness Center.

This study was approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects #30240. All participants consented to participate. The authors approve publication if accepted. The data that support the findings of this study are available from Dartmouth-Hitchcock but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Dartmouth-Hitchcock.

Financial Support:

This work was supported by The Dartmouth Clinical and Translational Science Institute (grant number UL1TR001086); the Department of Medicine and the Dartmouth Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Research Center (grant/award number: U48DP005018); the Friends of the Norris Cotton Cancer Center at Dartmouth and National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support (grant/award number: 5P30CA023108-37); and the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (grant/award number: K23AG051681).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

REFERENCES:

- 1.Batsis JA, McClure AC, Weintraub AB, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of a rural, pragmatic, telemedicine-delivered healthy lifestyle programme. Obes Sci Pract 2019; 5: 521–530. 2020/01/01. DOI: 10.1002/osp4.366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar Cheryl D., et al. Prevalence of Obesity and Severe Obesity Among Adults: United States, 2017–2018. 2020. [PubMed]

- 3.Lundeen EA, Park S, Pan L, et al. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Hong PS, et al. Behavioral treatment of obesity in patients encountered in primary care settings: a systematic review. JAMA 2014; 312: 1779–1791. 2014/11/05. DOI: 10.1001/jama.2014.14173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Batsis JA, Pletcher SN and Stahl JE. Telemedicine and primary care obesity management in rural areas - innovative approach for older adults? BMC Geriatr 2017; 17: 6. 2017/01/07. DOI: 10.1186/s12877-016-0396-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roettl J, Bidmon S and Terlutter R. What Predicts Patients’ Willingness to Undergo Online Treatment and Pay for Online Treatment? Results From a Web-Based Survey to Investigate the Changing Patient-Physician Relationship. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18: e32. 2016/02/06. DOI: 10.2196/jmir.5244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qureshi AA, Brandling-Bennett HA, Wittenberg E, et al. Willingness-to-pay stated preferences for telemedicine versus in-person visits in patients with a history of psoriasis or melanoma. Telemed J E Health 2006; 12: 639–643. 2007/01/26. DOI: 10.1089/tmj.2006.12.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chang J, Savage SJ and Waldman DM. Estimating Willingness to Pay for Online Health Services with Discrete-Choice Experiments. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2017; 15: 491–500. 2017/03/16. DOI: 10.1007/s40258-017-0316-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Government U. Census Bureau Statistics.

- 10.H J, L S and R. Amulet: An Energy-Efficient, Multi-applicaiton Wearable Platform. 14th ACM Conference on Embedded Network Sensor Systems CD-ROM-SenSys ‘16. 2016, p. 216–229. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buzza c, Ono S, Turvey C, et al. Distance is relative: unpacking a principal barrier in rural healthcare. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen MD, Ryan DH, Apovian CM, et al. 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS Guideline for the Management of Overweight and Obesity in Adults. Circulation 2014; 129: S102–S138. DOI: 10.1161/01.cir.0000437739.71477.ee. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Expansion of Medicare Telehealth Services for CY 2012. 2011. : U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Donelan K, Barreto EA, Sossong S, et al. Patient and clinician experiences with telehealth for patient follow-up care. The American journal of managed care 2019; 25: 40–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jurjevich J. Confronting Statistical Uncertainty in Rural America: Toward More Certain Data-Driven Policymaking Using American Community Survey (ACS) Data. 2019. DOI: 10.1007/978-981-13-9231-3_7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arize I, Onwujekwe O. Acceptability and willingness to pay for telemedicine services in Enugu state, southeast Nigeria. Digit Health. epub ahead of print 27 June 2017. DOI: 10.1177/2055207617715524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snoswell CL, Whitty JA, Caffery LJ, Loescher LJ, Gillespie N, Janda M. Direct-to-consumer mobile teledermoscopy for skin cancer screening: Preliminary results demonstrating willingness-to-pay in [DOI] [PubMed]