Abstract

This study used data from the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey to examine the association between adolescent marijuana, tobacco, and alcohol use and suicidal ideation and attempts over a period of six years (2011–2017), as attitudes and laws became more permissive of marijuana use. We used logistic regression to control for possible confounders, estimate marginal prevalence ratios (PR’s), and assess changes over time. Marijuana was more strongly associated with suicide attempts than ideation, and more frequent use was associated with significantly greater risk. The effect has not changed substantively since 2011, despite changing attitudes toward marijuana. Marijuana is broadly comparable to other substances: results for tobacco were similar, though frequent alcohol use had a significantly stronger association than other substances.

Keywords: Adolescent, alcohol, cannabis, tobacco, suicide, attempted

Suicide is the tenth leading cause of death in the US, but it is the second leading cause of death among youth 10–24 years of age (CDC, 2020). In 2018 there were 6,807 deaths (among youth 10–24 years) and an estimated 208,218 non-fatal suicide attempts treated in hospital emergency departments by this same age group (CDC, 2020). Not all attempts receive formal medical care, and researchers estimate that among adolescents there are between 50 and 100 total attempts for every suicide death (AAP, 2000). This estimate suggests 300,000 to 600,000 suicide attempts among youth occur per year. Even non-fatal attempts result in a significant burden of morbidity; attempts can result in lasting disability, injury or poisoning that requires expensive medical intervention, and significant psychological distress even when the physical harm is less severe. Suicide and intentional self-harm, therefore, represent an important adolescent health problem.

Consumption of tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana in adolescence have all been associated with suicide attempts. However, there exist important gaps in the literature on marijuana specifically. Many studies lump marijuana with other illicit substances (Gart & Kelly, 2015; Hallfors et al., 2004; Manzo, Tiesman, Stewart, Hobbs, & Knox, 2015). While a significant association between marijuana and suicide attempts has been found, the data come from surveys administered in 1994–1995, over 20 years ago (Borowsky, Ireland, & Resnick, 2001; Hallfors et al., 2004). These are important limitations because the US is currently undergoing a cultural and legal shift toward treating marijuana more like alcohol and tobacco than other illicit drugs. In 2012, Colorado and Washington became the first US states to legalize recreational marijuana use for adults 21 years and older. Currently, eight states and the District of Columbia have legalized marijuana for recreational use, and an additional twelve states have legalized marijuana for medical use and decriminalized recreational use. 64% of Americans support marijuana legalization, the highest proportion ever recorded, and more than one in five Americans live in a state where they can legally use marijuana (McCarthy, 2017). Only one study we are aware of has looked at marijuana use and suicide attempts in the context of these changing norms. Researchers in Colorado, a state with among the most liberal marijuana laws and a suicide rate higher than the national average, found no significant association between the number of medical marijuana registrants (a proxy for marijuana use) and the number of suicide deaths per county (Rylander, Valdez, & Nussbaum, 2014). But this study is limited by lacking data on individual marijuana use and suicide attempts, and did not separate adolescents from adults.

Studies of tobacco and alcohol use in adolescence are more robust. Epidemiologic studies have shown suicide attempts to be associated with current smoking (Gilreath, Connell, & Leventhal, 2012; Huang et al., 2017). Numerous studies have shown an association between suicide attempts and binge drinking (Aseltine, Schilling, James, Glanovsky, & Jacobs, 2009; Schilling, Aseltine, Glanovsky, James, & Jacobs, 2009; Windle, 2004), although the evidence for lower intensity drinking is less robust (Cash & Bridge, 2009). In a WHO study of 32 countries, past 30 day smoking and alcohol consumption were both associated with increased odds of past 12 month suicidal ideation and planning, consistent across geographic regions (McKinnon, Gariepy, Sentenac, & Elgar, 2016). Interestingly, higher levels of consumption (smoking >5 days or drinking >2 days) did not substantially increase the risk of suicidal ideation compared to minimal substance use. Finally, a recent survey of over 21,500 adolescents in Mexico revealed that current use and any history of both smoking and alcohol consumption were associated with significantly increased odds of lifetime suicide attempt (Valdez-Santiago et al., 2018). The current study fills a gap in the literature by measuring the association between marijuana use and suicidal ideation and attempts among US high school students from 2011 to 2017, a period of changing attitudes toward and legal regulation of marijuana. The stability of this association over time is assessed, and marijuana use is compared to use of tobacco and alcohol to contextualize the magnitude of effect.

METHODS

Data Source

We used data from the CDC’s National Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) (Kolbe, Kann, & Collins, 1993) years 2011–2017 for this study. The YRBS is a nationally-representative survey of American high school students (grades 9–12) conducted biennially (CDC, 2017). The survey asks students about a variety of health behaviors and risk factors, including diet and exercise, sexual activity, experience of bullying and other violence, substance use, and suicidal ideation and attempts. A three-stage cluster sampling design is used to sample from all public and private high schools in all 50 US states. Results are weighted to account for nonresponse and oversampling of ethnic minority students. The overall response rates for 2011, 2013, 2015, and 2017, respectively, were 71% (CDC, 2012), 68% (CDC, 2014), 60% (CDC, 2016a), and 60% (CDC, 2018).

Exposures

Our exposures of interest included past 30-day use of cigarettes, cigars/cigarillos, chewing tobacco/snuff/dip, electronic vaping products (2015 and 2017 data only), alcohol— any quantity, alcohol—5 or more drinks in a row, and marijuana. Students responded to the survey indicating the number of days they used each substance in the past 30 days, except for marijuana, in which case students indicated the number of times they used. We collapsed all responses into the following categories: 0 days/times, 1–2 times, 3–9, 10–19, and 20+ times.

Outcomes

Our outcomes of interest were suicidal ideation, plans, attempts, and attempts requiring medical attention (collectively referred to as suicide-related outcomes) in the past 12 months. Students indicated if they had: seriously considered suicide, planned a suicide attempt, attempted suicide, and had made a suicide attempt that resulted in injury or poisoning that had to be treated by a doctor. Seriously considering suicide and planning an attempt were binary variables (yes/no). Students reported the number of suicide attempts they had made in the past 12 months. We then dichotomized these responses to indicate any/no attempts. Students were only asked about attempts requiring medical attention if they endorsed at least one suicide attempt, but this variable was recoded such that the denominator was all students with a non-missing response for suicide attempts.

Covariates

We included sex (male/female), grade (9–12), race, experience of bullying, and a depression surrogate as covariates to mitigate potential confounding. The YRBS race/ethnicity categories were: White, Black/African American, Hispanic, Asian, American Indian/ Alaskan Native, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, mixed/non-Hispanic, mixed/Hispanic. Due to sample size concerns, we combined some racial/ethnic groups. We combined American Indian/Alaskan Natives and Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islanders into a single Native category and mixed/non-Hispanic and mixed/Hispanic into a single Mixed Race/ Ethnicity category. Students indicated whether they had been bullied on school property or electronically bullied in the past 12 months; students who endorsed either were coded as having been bullied. Students also indicated whether, in the past 12 months, they had felt sad or hopeless almost every day for at least 2 weeks in a row, to the point they stopped doing some usual activities. Students who answered affirmatively were considered to have experienced depressed mood.

Data Analysis

Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated for all pairs of substances. Only binge drinking and any alcohol were highly correlated (r>0.6), so each exposure was analyzed separately. We calculated weighted population proportions of all variables and tested for differences by sex and year using Chi-squared tests. Logistic regression was used to model the association between the use of each substance and each suicide-related outcome. Initial models included substance use, sex, and an interaction term.

We used multivariate logistic regression to control for the covariates described (sex, race/ethnicity, grade, bullying, depressed mood, and survey year). No covariates were significantly collinear in the final models. Multivariate models were not stratified by sex because the bivariate analyses did not reveal significant sex differences in the effect of substance use. Models incorporating interaction terms for marijuana use with survey year were used to assess the stability of the marijuana/suicide-related outcomes association over time. Because the prevalence of some outcomes were relatively high, prevalence ratios were calculated from the average marginal predictions of the fitted logistic regression model, as described elsewhere (Bieler, Brown, Williams, & Brogan, 2010). Prevalence ratios are better approximations of the true parameter of interest, population risk ratios, than are odds ratios when the prevalence of the outcome is high. We corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni adjustment to preserve an overall alpha of 0.05.

All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.4 and SUDAAN 11.0.1. SUDAAN allows for the correct analysis of data from complex survey designs. The CDC’s guide for analyzing YRBS data (CDC, 2016b) was followed for setting the SUDAAN model parameters: Taylor Series Linearization was used for variance estimation, and the design was set to WR (with replacement at first stage).

RESULTS

Descriptive Analyses

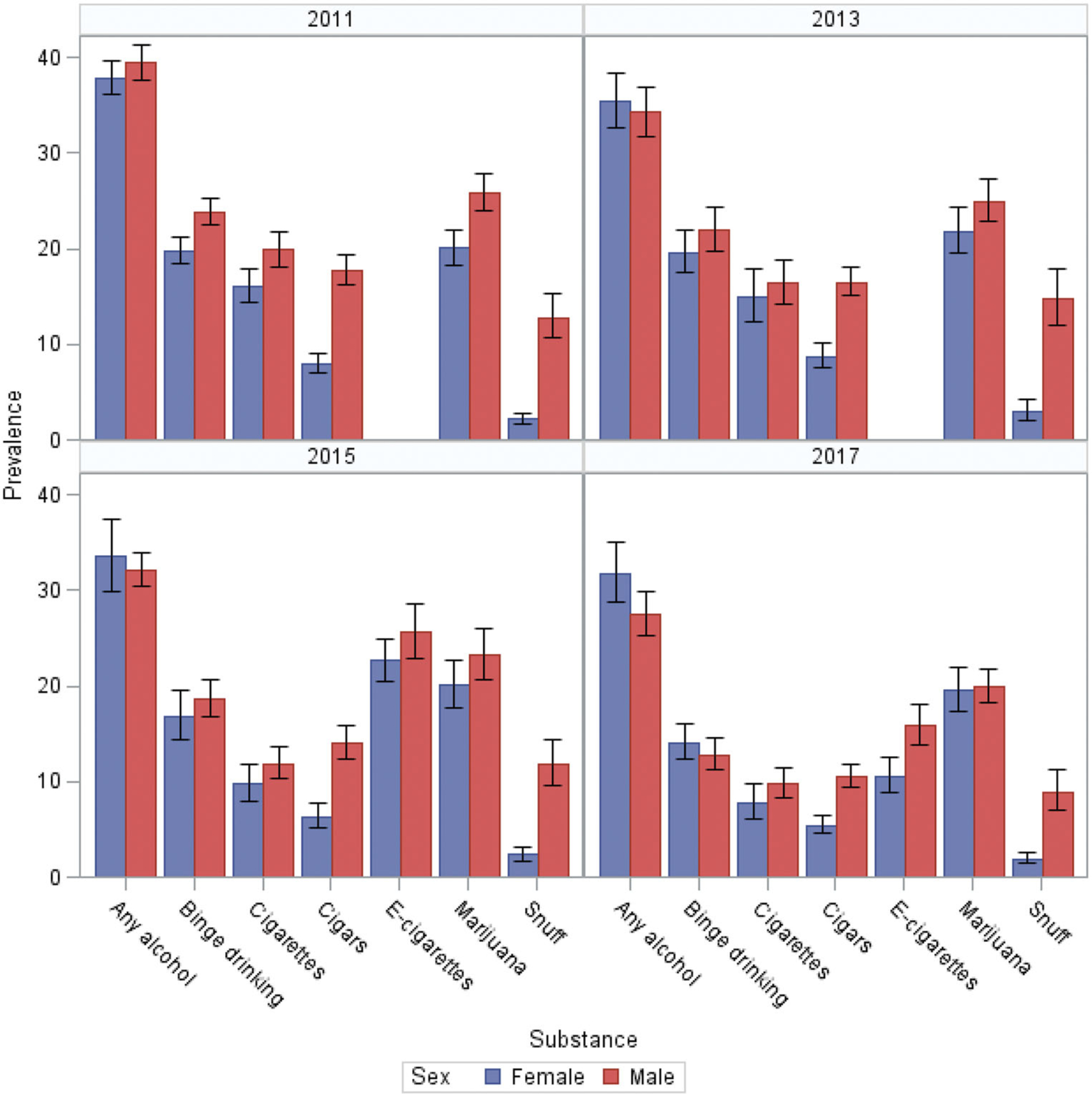

Sex, race/ethnicity, grade, bullying and depressed mood proportions did not vary significantly across the four survey years, and so consolidated demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The prevalence of substance use stratified by sex and survey year can be seen in Figure 1. Use of all tobacco products was significantly more prevalent among boys than girls. There was no significant sex difference in binge drinking; there was no sex difference in any drinking for most years, but in 2017 prevalence of any alcohol use was higher among girls. Marijuana use was more common among boys in 2011, but by 2017 there was no sex difference due to a small but significant decline in use among boys. Prevalence of marijuana use among girls was stable across time, with prevalence ranging 20–22%. Prevalence of use among boys was 26% in 2011 and dropped to 20% in 2017. In 2017, prevalence of any alcohol use was 28% among boys and 32% among girls; prevalence of binge drinking was 13%. Prevalence of cigarette smoking was 10% among boys and 8% among girls; cigars was 11% and 5%, electronic vaping was 16% and 11%; and snuff/chewing tobacco was 9% and 2%.

TABLE 1.

Study population characteristics—unweighted N and weighted proportion (95% CI).

| Female | Male | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 29,612 | N = 29,467 | ||

| 49.4% (48.2–50.6%) | 50.6% (49.4–51.8%) | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| White | 12,330 | 12,357 | 0.0886 |

| 55.4% (52.1–58.6%) | 54.9% (51.9–57.9%) | ||

| Black | 5,192 | 5,010 | |

| 13.8% (12.3–15.5%) | 13.9% (12.3–15.7%) | ||

| Hispanic | 3,973 | 3,883 | |

| 9.8% (8.4–11.4%) | 9.9% (8.7–11.2%) | ||

| Asian | 1,132 | 1,108 | |

| 3.3% (2.7–4.1%) | 3.5% (2.9–4.2%) | ||

| Native | 519 | 665 | |

| 1.3% (1.0–1.7%) | 1.6% (1.3–2.0%) | ||

| Mixed | 5,982 | 5,799 | |

| 16.5% (15.2–17.9%) | 16.2% (15.0–17.6%) | ||

| Grade in school | |||

| 9th | 7,682 | 7,568 | 0.3710 |

| 27.0% (26.1–28.0%) | 27.8% (26.8–28.8%) | ||

| 10th | 7,302 | 7,164 | |

| 25.7% (25.0–26.5%) | 25.7% (24.6–26.8%) | ||

| 11th | 7,325 | 7,494 | |

| 24.0% (23.3–24.7%) | 23.8% (23.2–24.4%) | ||

| 12th | 7,176 | 7,035 | |

| 23.3% (22.6–23.9%) | 22.7% (22.0–23.4%) | ||

| Bullying in past 12 months | |||

| Yes | 8,387 | 5,567 | <0.0001 |

| 31.2% (30.1–32.3%) | 20.3% (19.5–21.2%) | ||

| Depressed mood in past 12 months | |||

| Yes | 11,621 | 6,311 | <0.0001 |

| 39.0% (37.5–40.4%) | 21.0% (20.2–21.8%) |

Figure 1.

30 day prevalence of substance use with 95% confidence intervals, by sex.

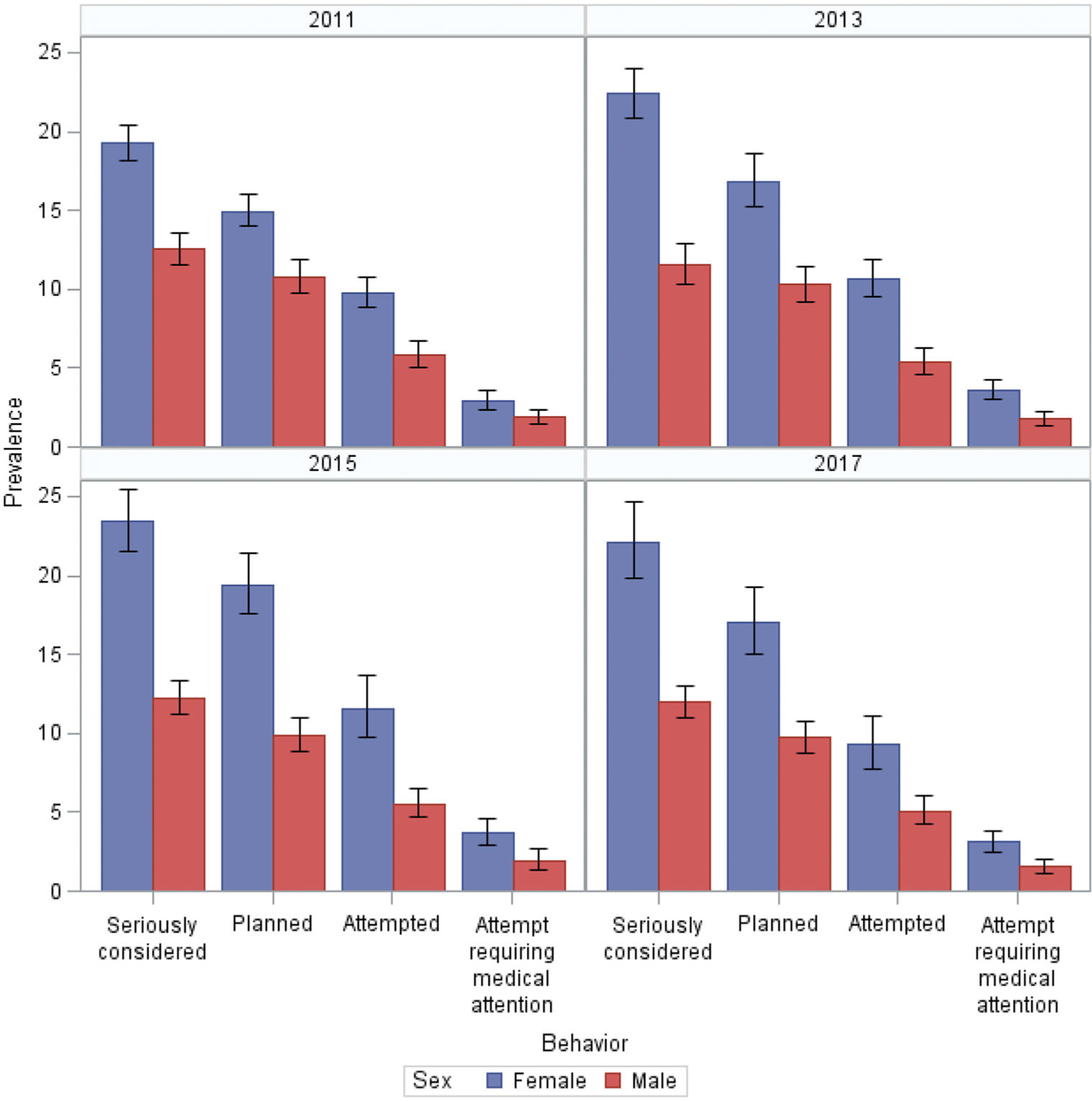

The prevalence of suicide-related outcomes stratified by sex and survey year can be seen in Figure 2. Suicide-related outcomes were significantly more prevalent among girls than boys. In 2017 12% of boys and 22% of girls seriously considered suicide; 10% of boys and 17% of girls planned a suicide attempt; 5% and 9% attempted suicide; and 2% and 3% had an attempt that required medical attention.

Figure 2.

12 month prevalence of suicide-related outcomes with 95% CI, by sex.

Modeling Substance Use by Sex

In the initial models, use of all substances were associated with all outcomes (data not shown). All substance with sex interaction terms were nonsignificant for considered, planned, and attempted suicide. For suicide attempt requiring medical attention, interaction terms were significant (p<0.05) for cigarettes, snuff, and binge drinking, and suggestive (p<0.1) for e-cigarettes and any alcohol. Because the interaction was not significant for marijuana, which is the focus of the study, this possible effect modification is noted, but was not explored.

Multivariate Models

Multivariate logistic regression controlling for sex, race/ethnicity, grade in school, bullying and depressed mood in previous 12 months, and survey year was used to generate prevalence ratios (PR’s) for each outcome. The full list of PR’s is shown in Table 2. All substances were significantly associated with suicidal ideation, planning, and attempts.

TABLE 2.

Prevalence ratios (95% confidence intervals) from multivariate logistic regression models.a

| Substance use past 30 days (ref = 0 days) | Marijuana | Cigarette | Cigar | Snuff | E-cigarette | Any alcohol | Binge drinking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seriously considered suicide | |||||||

| 1–2 days | 1.32 (1.23–1.41) | 1.29 (1.18–1.42) | 1.21 (1.11–1.33) | 1.26 (1.10–1.44) | 1.09 (0.97–1.22) | 1.28 (1.21–1.37) | 1.28 (1.21–1.36) |

| 3–9 days | 1.38 (1.27–1.50) | 1.49 (1.35–1.65) | 1.48 (1.32–1.65) | 1.40 (1.21–1.62) | 1.24 (1.10–1.39) | 1.40 (1.30–1.51) | 1.34 (1.22–1.48) |

| 10–19 days | 1.38 (1.23–1.54) | 1.58 (1.37–1.83) | 1.29 (1.07–1.55) | 1.28 (1.01–1.62) | 1.29 (1.08–1.55) | 1.43 (1.26–1.62) | 1.70 (1.44–2.01) |

| 20+ days | 1.54 (1.43–1.65) | 1.75 (1.61–1.91) | 1.69 (1.51–1.89) | 1.43 (1.29–1.59) | 1.63 (1.45–1.84) | 1.90 (1.65–2.20) | 2.04 (1.73–2.40) |

| Planned suicide | |||||||

| 1–2 days | 1.43 (1.30–1.56) | 1.26 (1.11–1.42) | 1.22 (1.10–1.36) | 1.25 (1.09–1.43) | 1.25 (1.08–1.45) | 1.26 (1.18–1.35) | 1.31 (1.22–1.41) |

| 3–9 days | 1.45 (1.30–1.61) | 1.67 (1.48–1.89) | 1.54 (1.37–1.74) | 1.42 (1.18–1.71) | 1.33 (1.16–1.55) | 1.47 (1.36–1.59) | 1.41 (1.27–1.57) |

| 10–19 days | 1.49 (1.31–1.69) | 1.67 (1.43–1.95) | 1.28 (1.04–1.57) | 1.27 (0.95–1.70) | 1.57 (1.25–1.97) | 1.62 (1.40–1.87) | 1.82 (1.42–2.27) |

| 20+ days | 1.62 (1.50–1.75) | 1.78 (1.60–1.97) | 2.00 (1.79–2.24) | 1.54 (1.31–1.82) | 1.76 (1.54–2.01) | 2.34 (2.03–2.70) | 2.55 (2.15–3.02) |

| Attempted suicide | |||||||

| 1–2 days | 1.65 (1.46–1.86) | 1.78 (1.55–2.04) | 1.81 (1.56–2.09) | 1.95 (1.60–2.39) | 1.25 (1.00–1.55) | 1.50 (1.34–1.69) | 1.75 (1.58–1.93) |

| 3–9 days | 2.11 (1.85–2.41) | 2.41 (2.05–2.83) | 2.31 (1.97–2.72) | 1.96 (1.57–2.44) | 1.94 (1.61–2.34) | 1.98 (1.76–2.23) | 1.91 (1.67–2.20) |

| 10–19 days | 2.13 (1.80–2.51) | 2.79 (2.25–3.45) | 2.53 (1.92–3.35) | 1.97 (1.49–2.60) | 1.94 (1.42–2.64) | 1.98 (1.63–2.40) | 2.40 (1.84–3.12) |

| 20+ days | 2.64 (2.37–2.93) | 2.79 (2.48–3.13) | 3.35 (2.89–3.90) | 2.59 (2.19–3.06) | 2.45 (1.98–3.04) | 4.89 (4.05–5.91) | 5.36 (4.22–6.80) |

| Attempt requiring medical attention | |||||||

| 1–2 days | 1.98 (1.55–2.52) | 2.35 (1.82–3.05) | 2.02 (1.55–2.64) | 2.47 (1.81–3.37) | 1.86 (1.24–2.78) | 1.88 (1.55–2.27) | 2.13 (1.79–2.55) |

| 3–9 days | 2.52 (1.98–3.21) | 2.81 (2.14–3.69) | 3.19 (2.51–4.06) | 3.47 (2.51–4.79) | 2.61 (1.91–3.56) | 2.68 (2.15–3.33) | 3.31 (2.65–4.14) |

| 10–19 days | 3.15 (2.40–4.12) | 4.91 (3.37–7.16) | 4.37 (2.94–6.49) | 3.40 (2.18–5.29) | 3.28 (1.96–5.49) | 4.11 (3.03–5.57) | 4.94 (3.52–6.92) |

| 20+ days | 4.51 (3.65–5.58) | 5.30 (4.34–6.47) | 5.48 (4.34–6.93) | 5.15 (4.01–6.60) | 3.52 (2.45–5.06) | 10.8 (8.28–14.2) | 11.6 (8.47–15.9) |

Models controlled for sex, race/ethnicity, grade, bullying, depressed mood, and survey year

Use of marijuana and other substances was more strongly associated with suicide attempts than ideation. PR’s were very similar between considered and planned suicide, were higher for attempted suicide, and higher still for attempts requiring medical attention. For seriously considered suicide PR for the lowest exposure level (1–2 days vs 0 days) was 1.3 (95% CI: 1.2–1.4), for planned suicide 1.4 (1.3–1.6), attempted suicide 1.7 (1.5–1.9), and attempt requiring medical attention 2.0 (1.6–2.5). For other substances PR’s ranged 1.1–1.3 for considered, 1.2–1.3 for planned, 1.3–2.0 for attempted, and 1.9–2.4 for attempts requiring medical attention.

A dose response was observed, with higher PR’s for frequent use compared to infrequent use in past 30 days. For seriously considered suicide, PR for the highest exposure level (20+ days) was 1.5 (1.4–1.7), for planned suicide 1.6 (1.5–1.8), for attempted 2.6 (2.4–2.9), and for medical attempt 4.5 (3.7–5.6). At high frequency of use alcohol had a stronger association with all suicide-related outcomes than tobacco or marijuana. For considered suicide PR’s for tobacco ranged 1.4–1.8 and for alcohol 1.9–2.0; for planned suicide for tobacco 1.5–2.0 and for alcohol 2.3–2.6; for attempted, tobacco 2.5–3.4 and alcohol 4.9–5.4; and for medical attempt, tobacco 3.5–5.5 and alcohol 10.8–11.6. For intermediate levels of use, PR’s for all substances fell between either extreme, though there was often overlap between confidence intervals. Again, see Table 2 for details. When controlling for tobacco and alcohol use, marijuana PR’s were slightly attenuated but still significant (data not shown).

Marijuana Effects Over Time

Interaction terms for marijuana use with survey year were significant for all outcomes for high frequency use, but not low frequency use; model parameter estimates are shown in Table 3 and PR’s by year are shown in Table 4. From 2011 to 2017 the effect of high and intermediate exposure, but not low, was attenuated. For seriously considered suicide the PR for high exposure fell from 1.7 (1.6–1.9) to 1.4 (1.2–1.6); for planned suicide PR fell 1.8 (1.6–2.0) to 1.5 (1.3–1.7); for attempted suicide PR fell 3.2 (2.8–3.7) to 2.1 (1.7–2.7); and for attempts requiring medical attention PR fell 6.0 (4.3–8.3) to 3.4 (2.3–4.8).

TABLE 3.

Multivariate logistic regression for marijuana use.

| Model parameters | Seriously considered suicide | Planned suicide | Attempted suicide | Attempt requiring medical attention | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coef (β) | Std err | p Value | Coef (β) | Std err | p Value | Coef (β) | Std err | p Value | Coef (β) | Std err | p Value | |

| Intercept | −3.32 | 0.08 | <0.0001 | −3.44 | 0.09 | <0.0001 | −4.40 | 0.11 | <0.0001 | −6.18 | 0.20 | <0.0001 |

| Used 1–2 times (ref = 0) | 0.62 | 0.12 | <0.0001 | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.0080 | 0.56 | 0.19 | 0.0037 | 0.35 | 0.31 | 0.2555 |

| Used 3–9 times | 0.69 | 0.18 | 0.0002 | 0.82 | 0.18 | <0.0001 | 1.15 | 0.21 | <0.0001 | 1.29 | 0.34 | 0.0002 |

| Used 10–19 times | 0.66 | 0.21 | 0.0021 | 0.39 | 0.22 | 0.0725 | 1.45 | 0.25 | <0.0001 | 1.86 | 0.31 | <0.0001 |

| Used 20+ times | 1.06 | 0.14 | <0.0001 | 0.96 | 0.13 | <0.0001 | 1.81 | 0.17 | <0.0001 | 2.26 | 0.28 | <0.0001 |

| Female sex | 0.27 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.0001 | 0.32 | 0.06 | <0.0001 | 0.31 | 0.08 | 0.0003 |

| Black race (ref = white) | −0.08 | 0.05 | 0.1209 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.6243 | 0.47 | 0.08 | <0.0001 | 0.54 | 0.13 | 0.0001 |

| Hispanic | −0.14 | 0.06 | 0.0130 | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.2505 | 0.38 | 0.10 | 0.0003 | 0.40 | 0.16 | 0.0122 |

| Asian | 0.24 | 0.13 | 0.0532 | 0.37 | 0.12 | 0.0020 | 0.50 | 0.15 | 0.0011 | 0.57 | 0.20 | 0.0059 |

| Native | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.3996 | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.0851 | 0.60 | 0.13 | <0.0001 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 0.0566 |

| Mixed | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.0224 | 0.23 | 0.05 | <0.0001 | 0.52 | 0.07 | <0.0001 | 0.51 | 0.11 | <0.0001 |

| Grade in school | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.0014 | −0.05 | 0.02 | 0.0082 | −0.20 | 0.02 | <0.0001 | −0.17 | 0.04 | <0.0001 |

| Bullying | 0.86 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | 0.79 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | 0.96 | 0.05 | <0.0001 | 1.06 | 0.08 | <0.0001 |

| Depressed mood | 2.33 | 0.04 | <0.0001 | 2.09 | 0.05 | <0.0001 | 2.19 | 0.07 | <0.0001 | 2.25 | 0.13 | <0.0001 |

| Survey year | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.0264 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.1896 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.6972 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.3451 |

| Used 1–2*Survey year | −0.07 | 0.05 | 0.1324 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.6372 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.7382 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.2041 |

| Used 3–9*Survey year | −0.07 | 0.06 | 0.2937 | −0.12 | 0.07 | 0.0978 | −0.07 | 0.07 | 0.3515 | −0.11 | 0.12 | 0.3669 |

| Used 10–19*Survey year | −0.06 | 0.08 | 0.5120 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.3350 | −0.20 | 0.10 | 0.0618 | −0.26 | 0.12 | 0.0363 |

| Used 20+*Survey year | −0.14 | 0.06 | 0.0174 | −0.10 | 0.06 | 0.0663 | −0.21 | 0.08 | 0.0061 | −0.23 | 0.10 | 0.0272 |

TABLE 4.

Prevalence ratios (95% CI’s) for marijuana by year.a

| 2011 | 2013 | 2015 | 2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seriously considered suicide | ||||

| 1–2 days | 1.41 (1.29–1.54) | 1.35 (1.26–1.44) | 1.29 (1.20–1.39) | 1.23 (1.10–1.38) |

| 3–9 days | 1.47 (1.27–1.70) | 1.41 (1.28–1.55) | 1.35 (1.24–1.38) | 1.30 (1.14–1.48) |

| 10–19 days | 1.45 (1.23–1.70) | 1.40 (1.25–1.57) | 1.35 (1.18–1.54) | 1.31 (1.06–1.60) |

| 20+ days | 1.73 (1.55–1.92) | 1.59 (1.49–1.71) | 1.47 (1.35–1.60) | 1.36 (1.19–1.55) |

| Planned suicide | ||||

| 1–2 days | 1.39 (1.20–1.61) | 1.41 (1.28–1.56) | 1.44 (1.30–1.59) | 1.46 (1.25–1.70) |

| 3–9 days | 1.63 (1.40–1.90) | 1.51 (1.36–1.68) | 1.39 (1.23–1.58) | 1.29 (1.06–1.56) |

| 10–19 days | 1.40 (1.14–1.72) | 1.46 (1.28–1.68) | 1.54 (1.34–1.76) | 1.61 (1.32–1.95) |

| 20+ days | 1.79 (1.61–2.00) | 1.67 (1.55–1.80) | 1.56 (1.42–1.72) | 1.46 (1.25–1.70) |

| Attempted suicide | ||||

| 1–2 days | 1.60 (1.31–1.95) | 1.63 (1.43–1.85) | 1.66 (1.44–1.90) | 1.69 (1.36–2.08) |

| 3–9 days | 2.28 (1.86–2.79) | 2.17 (1.88–2.50) | 2.06 (1.79–2.38) | 1.96 (1.59–2.42) |

| 10–19 days | 2.56 (2.06–3.19) | 2.24 (1.91–2.63) | 1.94 (1.57–2.40) | 1.68 (1.20–2.36) |

| 20+ days | 3.21 (2.77–3.71) | 2.80 (2.54–3.01) | 2.43 (2.12–2.79) | 2.10 (1.67–2.65) |

| Attempt requiring medical attention | ||||

| 1–2 days | 1.59 (1.07–2.36) | 1.80 (1.39–2.35) | 2.04 (1.56–2.62) | 2.31 (1.61–3.30) |

| 3–9 days | 2.95 (1.96–4.45) | 2.67 (2.04–3.49) | 2.41 (1.86–3.13) | 2.18 (1.47–3.24) |

| 10–19 days | 4.26 (2.99–6.06) | 3.41 (2.61–4.46) | 2.73 (1.98–3.76) | 2.17 (1.34–3.50) |

| 20+ days | 5.97 (4.32–8.25) | 4.94 (3.94–6.20) | 4.07 (3.21–5.17) | 3.35 (2.34–4.77) |

Controlling for sex, race/ethnicity, grade, bullying, and depressed mood

DISCUSSION

The national data in the YRBS, combined with a large sample size and consecutive years of data collection, allowed us to examine the association between adolescent suicide-related outcomes and substance use at a level of detail not commonly seen in the literature. We were able to compare marijuana to other substances, separating different modalities of tobacco use and types of drinking, and compare by frequency of use within and between substances. Marijuana use remained associated with the outcomes even while controlling for alcohol and tobacco, and correlations between use of different substances were low to moderate. These facts suggest independent associations with suicide-related outcomes for all substances examined.

The importance of accounting for dose has been shown in other studies. In a previous study among US adolescents using latent class analysis, classes characterized by high levels of substance use were at greater risk of suicide attempts than classes with lower levels of use (Hallfors et al., 2004), as was seen in the current study. A study in Mexico also showed that more frequent marijuana use was associated with suicide attempts where infrequent use was not (Borges, Benjet, Orozco, Medina-Mora, & Menendez, 2017). Interestingly, in the Mexican study no association with alcohol use was seen, whereas in the current study alcohol, at high levels, showed the strongest association. However, the categories in the Mexican study were very rough: using less than once per month and at least 1–3 times per month, compared to the more precise categories the YRBS allows. Similarly, a WHO multi-country study showed associations with 30-day smoking and alcohol use, but no difference by frequency of use (McKinnon et al., 2016). The categories were again rough: smoking was 1–5 days and ≥6 days, alcohol was 1–2 days and ≥3 days. Accounting for dose with a reasonable degree of precision should be a key feature of future studies on adolescent substance use. This is important to capture the true effects of substance use and to compare between countries, where different cultural norms around substance use may, or may not, affect how substances are associated with suicidal behaviors or other health outcomes.

While not the focus of the study, we believe this is the first study to document an association between electronic vaping and suicidal behaviors. And while documenting an association between marijuana use and suicidal behaviors is not itself novel, the context of this study is, with the US more permissive of marijuana use than it has been for decades, justifying a reexamination of the role marijuana may play as a risk factor. Other strengths of this study include the ability to assess multiple suicide-related outcomes. The large sample size allowed for precise estimates of even comparatively rare events, like suicide attempts requiring medical attention. Analytic methods were used that better approximate the population risk ratio. And consecutive surveys allowed the evaluation of changes over time. We found that the association between marijuana and suicide attempts, but not ideation, has changed in the last few years, as cultural attitudes have become more permissive of marijuana use. No other substance saw change over time. The association of suicide-related outcomes with frequent marijuana use has attenuated; sporadic use remained unchanged. We hypothesize that as stigma decreases, there may be more users who are at extremely low risk of suicide-related behaviors (e.g., not especially impulsive or trying to self-medicate) who use marijuana recreationally. This hypothesis is bolstered by research showing that adolescents increasingly perceive marijuana as not harmful (Sarvet et al., 2018). However, the monthly prevalence of marijuana use has not increased since 2011, so there is no evidence of an influx of new, potentially qualitatively different users. Research using other nationally representative surveys has confirmed the observation that adolescent marijuana use is declining over time (Sarvet et al., 2018). It should also be noted that frequent marijuana use remains a significant risk factor, and based on the fact that alcohol and all forms of tobacco are also risk factors, it seems unlikely that this downward trend in risk for marijuana will continue indefinitely.

This study has limitations to consider. The most important is that the data are cross-sectional. Temporality of substance use and the suicide-related outcomes cannot be established, and so this study provides no evidence for a causal association between substance use and suicidal behavior. The data are self-reported and thus subject to recall bias, although the YRBS has demonstrated good test-retest reliability (Brener et al., 2002). Under- or over-reporting may affect prevalence estimates, although associations will be unbiased unless there is differential reporting. The exposures and outcomes are measured in different recall windows, though this is not uncommon in suicide research where the outcome is much less common than the exposures of interest, e.g., substance use (Hallfors et al., 2004; McKinnon et al., 2016). The degree to which results may be generalizable to suicide death is open to debate. Suicidal intent and lethal action are not perfectly correlated (Mościcki, 2001). Attempts resulting in significant injury are likely to be a reasonable proxy, but the fact remains that there may be different underlying risk processes between fatal and non-fatal suicide attempts. Finally, using national level data precludes our ability to attribute the change in effect of frequent marijuana use to any specific, state level legislative changes. There may also be specific regions of the country or sub-populations for whom the association between marijuana and the suicide-related outcomes is different than what is seen nationally.

This study suggests that, as a risk factor for adolescent suicidal behavior, marijuana is comparable to tobacco and alcohol, and has remained so even as cultural attitudes have begun to change. Future studies are needed with known temporal ordering of substance use and suicidal behaviors and ideally will apply causal inference methods to determine whether reducing adolescent substance use will be expected to reduce suicide attempts. Any future research on adolescent substance use, causal or not, should strive to capture gradations in frequency and quantity of substance use, as simple dichotomous indicators may mask true associations. Interestingly, alcohol use at high frequency was twice as strongly associated with suicide attempts as either tobacco or marijuana. This finding has implications for identifying the most at-risk youth for targeting of selective interventions. For example, in a feasibility study evaluating the Suicide Risk Screen (Thompson & Eggert, 1999) in 10 US high schools, the authors concluded that widespread use of the instrument was not practical primarily because it resulted in too many false positives requiring intervention from school staff (Hallfors et al., 2006). Part of the SRS score comes from responses to a 6-point scale on frequency of alcohol, marijuana, and other drug use. The SRS defines ≥4 as problematic alcohol use but ≥3 as problematic marijuana use, whereas results from the current study suggest that an alcohol score of 4 is associated with comparable risk to a marijuana score of 5, not 3. A better understanding of how risk factors are quantitatively associated with adolescent suicidal behavior may improve the targeting of preventive interventions and make them not only more effective but more feasible to implement in a real-world setting.

FUNDING

Mr. Kahn, a graduate student, was supported by the NIMH T32 Mental Health Services and Systems Training Program [Grant # T32MH109436] at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, and by NIMH [Grant # F31MH120973].

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- AAP. (2000). Suicide and suicide attempts in adolescents. Pediatrics, 105(4 Pt 1), 871–874. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10742340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aseltine RH Jr., Schilling EA, James A, Glanovsky JL, & Jacobs D (2009). Age variability in the association between heavy episodic drinking and adolescent suicide attempts: Findings from a large-scale, school-based screening program. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48(3), 262–270. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318195bce8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bieler GS, Brown GG, Williams RL, & Brogan DJ (2010). Estimating model-adjusted risks, risk differences, and risk ratios from complex survey data. American Journal of Epidemiology, 171(5), 618–623. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borges G, Benjet C, Orozco R, Medina-Mora ME, & Menendez D (2017). Alcohol, cannabis and other drugs and subsequent suicide ideation and attempt among young Mexicans. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 91, 74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.02.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky IW, Ireland M, & Resnick MD (2001). Adolescent suicide attempts: Risks and protectors. Pediatrics, 107(3), 485–493. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11230587. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.3.485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener ND, Kann L, McManus T, Kinchen SA, Sundberg EC, & Ross JG (2002). Reliability of the 1999 youth risk behavior survey questionnaire. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 31(4), 336–342. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00339-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash SJ, & Bridge JA (2009). Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. CurrentOpinion in Pediatrics, 21(5), 613–619. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833063e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2017). Youth risk behavior survey data. Retrieved from www.cdc.gov/yrbs

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2012). 2011 YRBS data user’s guide. Retrieved from ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/data/YRBS/2011/YRBS_2011_National_User_Guide.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2014). 2013 YRBS data user’s guide. Retrieved from ftp://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/DATA/YRBS/2013/YRBS_2013_National_User_Guide.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016a). 2015 YRBS data user’s guide. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2015/2015_yrbs_sadc_documentation.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016b). Software for analysis of YRBS data. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2015/2015_yrbs_analysis_software.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2018). 2017 YRBS data user’s guide. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2017/2017_YRBS_Data_Users_Guide.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2020). Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WHISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control (producer). Retrieved July 7, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- Gart R, & Kelly S (2015). How illegal drug use, alcohol use, tobacco use, and depressive symptoms affect adolescent suicidal ideation: A secondary analysis of the 2011 youth risk behavior survey. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(8), 614–620. doi: 10.3109/01612840.2015.1015697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilreath TD, Connell CM, & Leventhal AM (2012). Tobacco use and suicidality: Latent patterns of co-occurrence among black adolescents. Nicotine & Tobacco Research: Official Journal of the Society for Research on Nicotine and Tobacco, 14(8), 970–976. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors D, Brodish PH, Khatapoush S, Sanchez V, Cho H, & Steckler A (2006). Feasibility of screening adolescents for suicide risk in “real-world” high school settings. American Journal of Public Health, 96(2), 282–287. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.057281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallfors DD, Waller MW, Ford CA, Halpern CT, Brodish PH, & Iritani B (2004). Adolescent depression and suicide risk: Association with sex and drug behavior. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 27(3), 224–231. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YH, Liu HC, Sun FJ, Tsai FJ, Huang KY, Chen TC, … Liu SI (2017). Relationship between predictors of incident deliberate self-harm and suicide attempts among adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(5), 612–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe LJ, Kann L, & Collins JL (1993). Overview of the Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance System. Public Health Reports, 108 (Suppl 1), 2–10. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8210269. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzo K, Tiesman H, Stewart J, Hobbs GR, & Knox SS (2015). A comparison of risk factors associated with suicide ideation/attempts in American Indian and White youth in Montana. Archives of Suicide Research: Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 19(1), 89–102. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2013.840254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J (2017). Record-high support for legalizing marijuana use in U.S. Gallup News. Retrieved from http://news.gallup.com/poll/221018/record-high-support-legalizing-marijuana.aspx?g_source=Politics&g_medium=newsfeed&g_campaign=tiles. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon B, Gariepy G, Sentenac M, & Elgar FJ (2016). Adolescent suicidal behaviours in 32 low- and middle-income countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 94(5), 340–350F. doi: 10.2471/BLT.15.163295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mościcki EK (2001). Epidemiology of completed and attempted suicide: Toward a framework for prevention. Clinical Neuroscience Research, 1(5), 310–323. doi: 10.1016/S15662772(01)00032-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rylander M, Valdez C, & Nussbaum AM (2014). Does the legalization of medical marijuana increase completed suicide? The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 40(4), 269–273. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2014.910520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarvet AL, Wall MM, Keyes KM, Cerdá M, Schulenberg JE, O’Malley PM, … Hasin DS (2018). Recent rapid decrease in adolescents’ perception that marijuana is harmful, but no concurrent increase in use. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 186, 68–74. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.12.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schilling EA, Aseltine RH Jr., Glanovsky JL, James A, & Jacobs D (2009). Adolescent alcohol use, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. The Journal of Adolescent Health: Official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 44(4), 335–341. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson EA, & Eggert LL (1999). Using the suicide risk screen to identify suicidal adolescents among potential high school dropouts. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 38(12), 1506–1514. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199912000-00011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valdez-Santiago R, Solorzano EH, Iniguez MM, Burgos LA, Gomez Hernandez H, & Martinez Gonzalez A (2018). Attempted suicide among adolescents in Mexico: Prevalence and associated factors at the national level. Injury Prevention: Journal of the International Society for Child and Adolescent Injury Prevention, 24(4), 256–261. doi: 10.1136/injuryprev2016-042197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windle M (2004). Suicidal behaviors and alcohol use among adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 28(5 Suppl), 29S–37S. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15166634. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000127412.69258.ee [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]