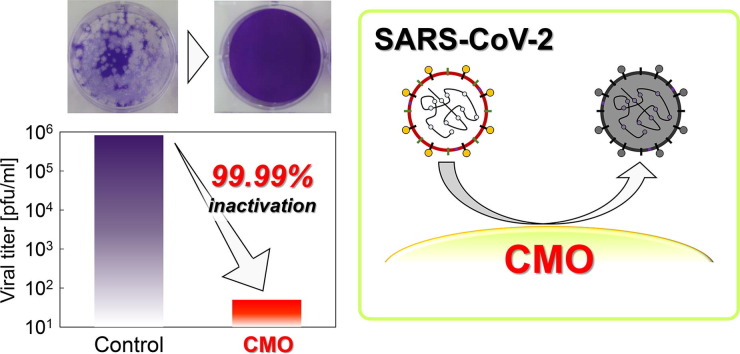

Graphical abstract

Keywords: Antiviral, Cerium, Complex oxide, Coronavirus, Molybdate

Abstract

Two cerium molybdates (Ce2Mo3O12 and γ-Ce2Mo3O13) were prepared using either polymerizable complex method or hydrothermal process. The obtained powders were almost single-phase with different cerium valence. Both samples were found to have antiviral activity against bacteriophage Φ6. Especially, γ-Ce2Mo3O13 exhibited high antiviral activity against both bacteriophage Φ6 and SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus, which causes COVID-19. A synergetic effect of Ce and molybdate ion was inferred along with the specific surface area as key factors for antiviral activity.

1. Introduction

Today, coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) has spread among humans worldwide. Suppression and prevention of spreading infection have become exceedingly important objectives. The need and demand for antiviral materials are increasing.

Recently, we used polymerizable complex method to combine La in rare-earth elements with molybdenum oxide to prepare La2Mo2O9 (hereinafter, LMO). We demonstrated that this material simultaneously exhibits hydrophobicity and antiviral activity against non-envelope type (bacteriophage Qβ, hereinafter denoted as Qβ) and envelope type (bacteriophage Φ6, hereinafter denoted as Φ6) viruses [1]. The material exhibited little cytotoxicity. However, its activity against Φ6 was found to be inferior to that against Qβ. Very recently, we improved the antiviral activity of this material against Φ6 by substituting Ce with La (La1.8Ce0.2Mo2O9, LCMO) [2]. Based on results of this study, cerium molybdates (CMO) were assessed as candidate materials with high antiviral activity against envelope type viruses such as influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses. To date, no report has described the antiviral activity of CMO.

Different from La, Ce is a multivalence element. Therefore, preparation of CMO powder samples with almost single crystal phase requires precise process control. For this study, we conducted numerous preliminary experiments and successfully prepared Ce2Mo3O12 using polymerizable complex method and γ-Ce2Mo3O13 through hydrothermal processing. After taking measurements of antiviral activity using these samples against Φ6, we evaluated the samples’ antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2 on γ-Ce2Mo3O13, LCMO, and MoO3 (99.0%; Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corp.). Based on the processing method, we designate these samples as CMO(PC) and CMO(HT), respectively, for Ce2Mo3O12 and γ-Ce2Mo3O13.

2. Experimental

Aqueous solutions of cerium(III) nitrate hexahydrate (Ce(NO3)3·6H2O; Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corp. (FWPCC),) and hexa-ammonium heptamolybdate tetrahydrate ((NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O; FWPCC) were mixed to set Ce:Mo = 2:3. Subsequently, citric acid (C6H8O7; FWPCC) was added to the mixed solution. The molar ratio of metal ion (Ce + Mo) to citric acid was 1:2. Then ethylene glycol (C2H6O2; FWPCC) was added to the solution so that the molar ratio of ethylene glycol to citric acid was 2:3. This solution was stirred at 80 °C for 6 h to facilitate esterification. The obtained precursor gel was dried at 200 °C for 21 h. The dried gel was fired at 550 °C for 12 h in ambient air, and was milled. Then CMO(PC) was obtained.

In hydrothermal processing, aqueous solutions of cerium (IV) ammonium nitrate (Ce(NH4)2(NO3)6; FWPCC) and (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O were mixed to set Ce:Mo = 2:3. The solution was placed into a Teflon reactor of a stainless steel autoclave, which was then heated to 160 °C for 5 h. After washing the obtained powder with water and ethanol, it was dried at 80 °C for 6 h. The dried powder was fired at 500 °C for 2 h in ambient air, and was milled. Then CMO(HT) was obtained.

Detailed information related to the characterization, activity evaluation, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) enzyme inactivation test, and cytotoxicity testing is presented in Supporting Information .

3. Results and discussion

Although several unknown peaks are visible in XRD patterns, the obtained powders were almost single phase (Fig. 1 (a)): peaks in the patterns were identified respectively as Ce2Mo3O12 (card No. 30–0303) and γ-Ce2Mo3O13 (card No. 31–0332)) for CMO(PC) and CMO(HT). The Mo/Ce molar ratios obtained from ICP (Table SI-1 in Supporting Information) were consistent with those of these compounds. Primary particle sizes of CMO(PC) were 0.5–1 µm (Fig. 1(b)). CMO(HT) possessed finer (approx. 100 nm particle size) spherical morphology than CMO(PC) (Fig. 1(c)). No specific microstructure was found in these particles from TEM observation (Fig. SI-1 in Supporting Information). The valences of Ce and Mo obtained from XPS are presented in Table SI-1. Almost all Ce in CMO(PC) was Ce(III), whereas Ce(III):Ce(IV) was almost 1:1 for CMO(HT). The ratio of Mo(IV):Mo(V):Mo(VI) was 0:23:77 for CMO(PC). The valence of Mo for CMO(HT) was almost Mo(VI). Deviations from the ideal valences suggest oxygen vacancy formation to compensate the charge balance at the surface of these powders. Photocatalytic decomposition activity was not obtained from these samples.

Fig. 1.

XRD patterns (a) and SEM micrographs of prepared powders: (b) CMO(PC) and (c) CMO(HT).

Results of pH and the dissolved ion concentration in 1/500 NB solution (see Supporting Information), with specific surface areas of the prepared CMO powders are presented in Table 1 . Those from LMO and LCMO obtained in our earlier study [2] are also presented in the table. The weak solvent acidity was attributable to molybdic acid formation [3]. The amounts of dissolved ions were CMO(HT) > CMO(PC), probably because of the different specific surface areas. The difference of dissolved Mo/Ce ratio (451/57 = 7.9 for CMO(HT), and 177/47 = 3.8 for CMO(PC)) might be attributable to valence difference of Ce and These values exceed that of the expected values (=3/2) of the complex oxides identified using XRD. The solubility difference for Mo and Ce corresponds to this trend [4]. We infer that some ions in the 1/500NB such as might be adsorbed or be absorbed to sample powders to compensate for deficient negative charges by excess dissolution of the molybdate ion.

Table 1.

Results of pH and dissolved ion concentration in 1/500 NB solution, with specific surface areas of prepared CMO powders.

| Sample | Specific surface area (m2/g) | pH | Dissolved ion concentration |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| La [μmol/L] | Ce [μmol/L] | Mo [μmol/L] | |||

| CMO(PC) | 3.0 | 4.31 | – | 47 | 177 |

| CMO(HT) | 14 | 3.94 | – | 57 | 451 |

| LCMO* | 10 | 5.77 | 75 | 0.4 | 112 |

| LMO* | 6.8 | 5.26 | 168 | – | 299 |

Fig. 2 presents results of antiviral activity against Φ6. The y-axis stands for the logarithm of the survival number of the virus. The activity order was CMO(HT) > CMO(PC) > LCMO > LMO. We reported a certain contribution of direct contact to the powder surface along with the dissolved ion effect for antiviral activity of LMOs against bacteriophage Φ6 [2]. Actually, CMO(HT) possesses higher specific surface area than other samples, which is one reason for its high activity. However, the order of activity does not simply follow that of the specific surface area. Rather, it follows that of dissolving amount of Ce ion, which suggests a Ce ion contribution. In our earlier study [2], CeO2 exhibited little activity against Φ6 despite dissolving Ce ion (4 μmol/l). The molybdate ions, dissolved in water with a weak acid pH range, form polyacids in the solution. Liu et al. demonstrated that heteropoly acids containing Ce exhibit strong inhibition activity against influenza virus [5], suggesting that the combination of Ce with Mo is another key factor supporting antiviral activity against Φ6. Judd et al. reported that polyacids adsorbed at the cation site of lysine residue in the active site by electrostatic interaction inactivated HIV viruses [6]. CMO(HT) possesses a higher concentration of Ce(IV) than CMO(PC). Ce(IV) and Mo(VI) form a heteropolyacid [CeMo12O42]8- under an acidic condition [7]. The valence of Ce might also be an important factor.

Fig. 2.

Antiviral activities of prepared powders against Φ6 (a), with photographs showing the change of plaque number for Φ6 by CMO(HT) after 18 h: (b) control and (c) with CMO(HT). Antiviral activities of LMO and LCMO were referred from ref. [2].

Fig. 3 presents the antiviral activity of CMO(HT), LCMO and MoO3 against SARS-CoV-2. Lysine exists at the portion of the active site of SARS-CoV-2 [8]. The activity order was CMO(HT) > MoO3 > LCMO. The antiviral activity of CHO(HT) is known to exceed that of MoO3. We evaluated and reported the specific surface area and ion dissolution amounts on this MoO3 in our earlier study [2]. Although the specific surface area of MoO3 (1.7 m2/g) is one order smaller than that of CMO(HT), the antiviral activity of CMO(HT) is more than two orders higher than that of MoO3 at 4 h. Moreover, the dissolved ion concentration of MoO3 (3992 μmol/l) is one order higher than that of CMO(HT). These results also suggest the contribution of Ce combined with Mo to the overall antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 3.

Antiviral activity of CMO(HT), LCMO and MoO3 against coronavirus (a), with photographs showing the change of plaque number for coronavirus by CMO(HT) after 4 h: (b) control and (c) with CMO(HT).

Both CMOs exhibited high ALP inactivation rates (Fig. SI-2 in Supporting Information). Moreover, ALP contains lysine residues, Chemical modification of lysine residues leads to ALP deactivation [9]. If molybdenum polyacids were to adsorb onto the lysine residues by Coulombic interaction, they would deactivate ALP as well as the viruses. None of these powders possesses cytotoxicity (Fig. SI-3 in Supporting Information).

4. Conclusion

For this study, we used polymerizable complex method or hydrothermal processing to prepare Ce2Mo3O12 and γ-Ce2Mo3O13. The prepared CMOs exhibited high antiviral activity against Φ6. Especially, that of γ-Ce2Mo3O13 was much higher than that of LMOs. The material exhibited strong antiviral activity against coronavirus. The specific surface area and appropriate combination of Ce with Mo are key factors supporting their high antiviral activity against these viruses.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Takuro Ito: Formal analysis, Data curation, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Kayano Sunada: Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Takeshi Nagai: Formal analysis, Methodology. Hitoshi Ishiguro: Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing - review & editing. Ryuichi Nakano: Formal analysis, Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Yuki Suzuki: Formal analysis, Methodology. Akiyo Nakano: Formal analysis, Methodology. Hisakazu Yano: Formal analysis, Investigation. Toshihiro Isobe: Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision. Sachiko Matsushita: Formal analysis. Akira Nakajima: Conceptualization, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Validation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the staff of the Center of Advanced Materials Analysis (CAMA) at the Tokyo Institute of Technology for various characterizations and for helpful discussion. This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (20H02432).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.matlet.2021.129510.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Matsumoto T., Sunada K., Nagai T., Isobe T., Matsushita S., Ishiguro H., Nakajima A. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019;378 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Matsumoto T., Sunada K., Nagai T., Isobe T., Matsushita S., Ishiguro H., Nakajima A. Mater. Sci. C. 2020;111 doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2020.111323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krishnamoorthy K., Premanathan M., Veerapandian M., Kim S.J. Nanotechnology. 2014;25(315101):1–10. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/25/31/315101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dean J.A., editor. Lange’s Handbook of Chemistry. 12th ed. McGraw-Hill Book Company; 1978. pp. 4–38. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu J., Mei W.-J., Xu A.-W., Tan C.-P., Shi S., Ji L.-N. Antiviral Res. 2004;62:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Judd D.A., Nettles J.H., Nevins N., Snyder J.P., Liotta D.C., Tang J., Ermolieff J., Schinazi R.F., Hill C.L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123(5):886–897. doi: 10.1021/ja001809e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sasaki Y. J. Cryst. Soc. Jpn. 1975;17:127–144. [in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshimoto F.K. Protein J. 2020;39:198–216. doi: 10.1007/s10930-020-09901-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H.-T., Xie L.-P., Yu Z.-Y., Xu G.-R., Zhang R.-Q. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005;37:1446–1457. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.