Key Points

Question

What factors are associated with real-life functioning in people with schizophrenia, and what are the implications for the implementation of management plans?

Findings

This 4-year cohort study, involving 618 clinically stable participants with schizophrenia, identified social and nonsocial cognition, avolition, and positive symptoms as the main baseline factors associated with real-life functioning at follow-up. Baseline everyday life skills were associated with changes in work skills at follow-up.

Meaning

Findings suggest that several variables associated with real-life functioning at follow-up are not routinely assessed and targeted by intervention programs and that personalized interventions aimed at promoting cognition and independent living should be an integral part of management programs for schizophrenia.

Abstract

Importance

The goal of schizophrenia treatment has shifted from symptom reduction and relapse prevention to functional recovery; however, recovery rates remain low. Prospective identification of variables associated with real-life functioning domains is essential for personalized and integrated treatment programs.

Objective

To assess whether baseline illness-related variables, personal resources, and context-related factors are associated with work skills, interpersonal relationships, and everyday life skills at 4-year follow-up.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This multicenter prospective cohort study was conducted across 24 Italian university psychiatric clinics or mental health departments in which 921 patients enrolled in a cross-sectional study were contacted after 4 years for reassessment. Recruitment of community-dwelling, clinically stable persons with schizophrenia was conducted from March 2016 to December 2017, and data were analyzed from January to May 2020.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Psychopathology, social and nonsocial cognition, functional capacity, personal resources, and context-related factors were assessed, with real-life functioning as the main outcome. Structural equation modeling, multiple regression analyses, and latent change score modeling were used to identify variables that were associated with real-life functioning domains at follow-up and with changes from baseline in these domains.

Results

In total, 618 participants (427 male [69.1%]; mean [SD] age, 45.1 [10.5] years) were included. Five baseline variables were directly associated with real-life functioning at follow-up: neurocognition with everyday life (β, 0.274; 95% CI, 0.207-0.341; P < .001) and work (β, 0.101; 95% CI, 0.005-0.196; P = .04) skills; avolition with interpersonal relationships (β, −0.126; 95% CI, −0.190 to −0.062; P < .001); positive symptoms with work skills (β, −0.059; 95% CI, −0.112 to −0.006; P = .03); and social cognition with work skills (β, 0.185; 95% CI, 0.088-0.283; P < .001) and interpersonal functioning (β, 0.194; 95% CI, 0.121-0.268; P < .001). Multiple regression analyses indicated that these variables accounted for the variability of functioning at follow-up after controlling for baseline functioning. In the latent change score model, higher neurocognitive abilities were associated with improvement of everyday life (β, 0.370; 95% CI, 0.253-0.486; P < .001) and work (β, 0.102; 95% CI, 0.016-0.188; P = .02) skills, social cognition (β, 0.133; 95% CI, 0.015-0.250; P = .03), and functional capacity (β, 1.138; 95% CI, 0.807-1.469; P < .001); better baseline social cognition with improvement of work skills (β, 0.168; 95% CI, 0.075-0.261; P < .001) and interpersonal functioning (β, 0.140; 95% CI, 0.069-0.212; P < .001); and better baseline everyday life skills with improvement of work skills (β, 0.121; 95% CI, 0.077-0.166; P < .001).

Conclusions and Relevance

Findings of this large prospective study suggested that baseline variables associated with functional outcome at follow-up included domains not routinely assessed and targeted by intervention programs in community mental health services. The key roles of social and nonsocial cognition and of baseline everyday life skills support the adoption in routine mental health care of cognitive training programs combined with personalized psychosocial interventions aimed to promote independent living.

This cohort study assess whether baseline illness-related variables, personal resources, and context-related factors are associated with work skills, interpersonal relationships, and everyday life skills at 4-year follow-up of a multicenter cross-sectional study involving community-dwelling persons with schizophrenia.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is no longer conceptualized as a progressive deteriorating illness. However, although clinical stability with persistent symptomatic remission is now considered a realistic outcome for affected people,1,2 the level of social, vocational, and everyday life functioning attained by the majority of individuals with schizophrenia is still poor.1,3,4,5,6

These findings have shifted the focus of clinical research on schizophrenia from psychopathological improvement and prevention of hospitalization to real-life functioning improvement and identification of its determinants.3,7,8,9,10,11,12,13 Several cross-sectional studies have shown that impairment in neurocognition and social cognition, currently conceptualized as separate cognitive domains,12,14 is associated with worse functioning in community-based activities.8,12,14,15,16,17,18,19,20 However, these cross-sectional studies did not enable the drawing of conclusions about the direction of causality.

In a cross-sectional study involving 921 community-dwelling people with schizophrenia,3 members of our group found that neurocognitive impairment has a strong association with real-life functioning. This association is independent from the avolition domain of negative symptoms, as well as from the positive and disorganization dimensions, and is mediated by numerous pathways involving social cognition, functional capacity, engagement with services, and stigma. Social cognition has a direct association with functioning, and besides mediating an association with neurocognition, it also mediates the association of disorganization.3 Once again, however, the cross-sectional study design prevented inferences about the direction of causality.

Some longitudinal studies have found that neurocognitive impairment is associated with functional outcome at 2 to 4 years from baseline,14,21,22,23,24 but others have not confirmed these results.25 These studies have used different measures of functional outcome. Fewer longitudinal studies have investigated the association between social cognition and real-life functioning.26,27

Regarding psychopathological variables, negative symptoms and disorganization have been found to be associated with real-life functioning in cross-sectional studies.11,28,29 Some longitudinal studies have shown that negative symptoms, in particular avolition or other measures of motivation and interest-related domains (such as anhedonia or asociality), have the strongest association with functioning and outweigh cognitive impairment as determinants of real-life functioning at follow-up.9,30,31,32 Improvement in negative symptoms is associated with amelioration of cognitive impairment in some studies.33,34 However, in most of those studies,30,31,32,33,34 negative symptoms were assessed using the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale or the Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms, which have several limitations, such as the inclusion of items (eg, difficulty in abstract thinking or attentional impairment) that overlap with cognitive dysfunctions.

The available evidence does not enable the drawing of solid conclusions regarding the variables associated with real-life functioning in people with schizophrenia across time owing to several methodological flaws: (1) most studies have modest sample sizes (N ≤ 150); (2) the assessment of cognitive functioning, disorganization, and negative symptoms is not always carried out using state-of-the-art instruments (eg, second-generation assessment instruments for negative symptoms, such as the Brief Negative Symptom Scale, or comprehensive cognitive assessment batteries, such as the Measurement And Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia Consensus Cognitive Battery); (3) social cognition impairment is not always evaluated; (4) most studies explore global functioning or only 1 of the real-life functioning domains, which might have distinct determinants; and (5) functional capacity is seldom included.

The present longitudinal study aimed to address some of these limitations and to assess whether baseline illness-related variables, personal resources, and context-related factors were associated with work skills, interpersonal relationships, and everyday life skills at 4-year follow-up. In a previous study based on the same data set,35 members of our group applied a network analysis to evaluate whether the pattern of associations among the variables investigated at baseline is retained at follow-up. This previous study did not assess whether baseline variables are associated with the levels of functioning at follow-up, which is the aim of the present study.

Methods

Participants

Of 26 Italian university psychiatric clinics or mental health departments involved in the network’s cross-sectional investigation,3 24 joined the follow-up study. All patients recruited by those 24 participating centers at baseline were asked to participate in the follow-up study. All participants fulfilled DSM-IV criteria for schizophrenia as ascertained by the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, patient version.36 Exclusion criteria are reported in eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1. The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees of the participating centers, and recruitment was carried out from March 2016 to December 2017. After receiving a comprehensive explanation of the study procedures and goals, all patients provided written informed consent obtained in a manner consistent with the Declaration of Helsinki.37 No one received compensation or was offered any incentive for participating in this study.

When participants in the baseline study could not be traced or were deceased, investigators were asked to fill in an ad hoc form reporting clinical information available at the last contact or, whenever possible, the cause of death. Participants were reassessed on all measures obtained at baseline (Table 1). A detailed description of the study assessment procedures is reported in eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1.

Table 1. Assessments Conducted at Both Baseline and Follow-up, and Measures Included in the Study as Independent Variables.

| Domain and variables | Instrument | Measure | Measures included as independent variables (baseline assessment) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illness-related factors | |||

| Positive dimension; disorganization dimension | Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale38 | Positive dimension39 (sum of the items delusions, hallucinations, grandiosity, and unusual thought content); disorganization39 (sum of the items conceptual disorganization, poor attention, difficulty in abstract thinking) | Positive dimension; disorganization dimension |

| Negative symptoms | Brief Negative Symptom Scale40,41 | Expressive deficit (sum of the subscales blunted affect and alogia); avolition (sum of the subscales anhedonia, asociality, and avolition) | Avolition |

| Depression | Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia42 | Total score | |

| Extrapyramidal symptoms | St Hans Rating Scale43 | Total score | |

| Neurocognition | MCCB44,45 | MCCB domain scores: speed of processing; verbal and spatial learning; reasoning and problem solving; attention; working memory | Neurocognitiona |

| Social cognition | MCCB44,45; MSCEIT managing emotion score; FEIT46; TASIT47 | MSCEIT managing emotion section score; FEIT total; TASIT-1; TASIT-2; TASIT-3 | Social cognitiona |

| Physical comorbidities | Physical Health Inventory48 | Any physical comorbidity | |

| Psychiatric comorbidities | Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV, Patient Edition36 | Any psychiatric comorbidity | |

| Assessment of personal resources | |||

| Resilience | RSA49 | RSA factors: perception of self; perception of the future; social competence; family cohesion | Resiliencea |

| Service engagement with mental health services | SES50 | SES total score | SES total score |

| Evaluation of context-related factors | |||

| Internalized stigma | ISMI51 | ISMI total score | ISMI total score |

| Available incentives | Count variable created to reflect the availability of a disability pension, access to family financial and practical support, and registration as disabled in employment lists | No. of available incentives | No. of available incentives |

| Assessment of functional capacity and real-life functioning | |||

| Functional capacity | UPSA-B52 | UPSA-B total score | UPSA-B total score |

| Real-life functioning | SLOF53 | SLOF domains of interpersonal relationships, everyday life skills, and work skills | SLOF domains of interpersonal relationships, everyday life skills, and work skills |

Abbreviations: FEIT, Facial Emotion Identification Test; ISMI, The Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness; MATRICS, Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia; MCCB, MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery; MSCEIT, Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test; RSA, Resilience Scale for Adults; SES, Service Engagement Scale; SLOF, Specific Level of Functioning Scale; TASIT, The Awareness of Social Inference Test; TASIT-1, TASIT part 1; UPSA-B, University of California San Diego Performance-Based Skills Assessment Brief.

Latent variables.

Statistical Analysis

Between-group comparisons were performed using the χ2 test, t test, or Mann-Whitney test, as appropriate. Within-participant comparisons were conducted using the paired-samples t test, Wilcoxon signed rank test, or McNemar test, as appropriate.

We used a structural equation model analytical strategy to identify the variables measured at baseline that were associated with real-life functioning at 4-year follow-up among those that had shown an association with functioning in a previous cross-sectional study conducted by members of our team.3 To this end, we expanded the cross-sectional structural equation model by adding the scores on the subscales everyday life skills, interpersonal relationships, and work skills of the Specific Level of Functioning Scale at follow-up (t1) as outcome variables. The list and the description of included independent variables are provided in Table 1. In the model presented in this study, we assessed all direct associations of the baseline variables with functioning at t1. Functioning at baseline (t0) and the association of baseline independent variables with function at t0 were also included in the model (within t0 associations).

Multiple regression analyses were then performed in which the scores on the subscales everyday life skills, interpersonal relationships, and work skills of the Specific Level of Functioning Scale at follow-up were the dependent variables. Independent variables were disorganization dimension, positive dimension, avolition, neurocognition composite, social cognition composite, functional capacity, incentives, internalized stigma, resilience composite, engagement with services, presence of any physical comorbidities, presence of any psychiatric comorbidities, and scores on the subscales everyday life skills, interpersonal relationships, and work skills of the Specific Level of Functioning Scale at baseline.

Latent change score (LCS) modeling was complementarily used to estimate determinants of changes in functioning. The LCS models change as a latent variable, thus reducing measurement error and susceptibility to low variance in observed variables. In the LCS model, the domains of real-life functioning—along with neurocognition, social cognition, functional capacity, avolition, and positive dimension—at baseline were modeled as independent variables. In this way, we were also able to test whether functioning was associated with change in other domains, which was not feasible in the structural equation model, in which an a priori pattern of associations was used.

For both structural equation model and LCS analyses, the goodness of fit to the data was evaluated using the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index, and the Tucker-Lewis index, and full-information maximum likelihood was used to handle missing data. A 2-sided P ≤ .05 was considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed from January to May 2020. Descriptive statistics were obtained using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp). We used Mplus, version 7.4 (Muthén & Muthén), for structural equation modeling, and the R package lavaan54 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing) for LCS modeling, adapting the scripts provided by Kievit et al.55 Further details on the structural equation model and LCS as well as on control analyses are included in eAppendix 1 in Supplement 1.

Results

Study Population

Of 921 individuals recruited at baseline, 618 participated in the present study. Of 303 individuals who were not included in the present study, 98 refused to participate; 75 had been referred to a different psychiatrist or mental health department and could not be contacted; 36 had changed residence and reported logistic difficulties in joining the study; 24 were clinically unstable or had recently changed pharmacological treatment; 19 were deceased; 10 could not be traced; 4 showed a significant cognitive decline, possibly due to dementia; and 2 reported substance abuse in the 6 months preceding the interview. For 11 individuals, no reason for dropout was recorded. Lastly, 24 patients had been recruited by 2 centers that did not participate in the follow-up study.

The baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of included participants are reported in eTable 1 in Supplement 1. Of 618 participants, 427 (69.1%) were male, and the mean (SD) age at follow-up was 45.1 (10.5) years. There was no age × sex × center interaction. Recruited participants did not differ significantly from 303 patients who were not assessed at follow-up on sociodemographic characteristics, psychopathology, context-related variables, and personal resources, but the recruited participants typically had better interpersonal (t = −3.51; 95% CI, −2.32 to −0.66; P < .001) and work functioning (t = −2.68; 95% CI, −2.02 to −0.31; P = .008) skills as well as higher engagement with mental health services (t = 3.98; 95% CI, 1.10-3.23; P < .001).

Within-participant comparisons of baseline vs follow-up P values showed that patients had a stable mean (SD) level of education (11.76 [0.13] vs 11.72 [0.14] years; P = .51), a slight decrease in the number (%) of supported housing (76 [12.4%] vs 62 [10.1%]; P = .03) and legal (52 [8.5%] vs 8 [1.3%]; P < .001) problems, a modest increase in working status (170 [28.9%] vs 208 [35.4%]; P < .001) and in stable affective relationships (92 [15.1%] vs 115 [18.8%]; P = .004), and no difference in the use of second-generation antipsychotic treatment (432 [69.9%] vs 441 [71.4%]; P = .43) (eTable 2 in Supplement 1). As reported in a previous study,35 participants improved at follow-up, with respect to baseline, on positive symptoms (9.7 [4.7%] vs 8.4 [4.3%]; P < .001), avolition (20.7 [9.6%] vs 18.5 [9.7%]; P < .001), disorganization (2.6 [1.4%] vs 2.4 [1.4%]; P = .001), internalized stigma (2.2 [0.4%] vs 2.1 [0.5%]; P < .001), and verbal learning (19.1 [5.4%] vs 19.5 [5.5%]; P = .03) while showing a slight decline in functioning (everyday life skills, 46.2 [8.3%] vs 45.2 [9.5%]; P = .001; and interpersonal relationships, 22.8 [5.9%] vs 22.2 [6.0%]; P = .02) and in the perception of self component of resilience (18.1 [5.3%] vs 15.4 [4.6%]; P < .001). They also exhibited an increase in the number of incentives received (1.95 [1.1%] vs 1.82 [1.1%]; P = .004).

Structural Equation Model

The final structural equation model had a very good fit to the data (RMSEA = 0.038 [95% CI, 0.033-0.042]; comparative fit index, 0.957; Tucker-Lewis index, 0.949). The variance of real-life functioning at follow-up explained by the model was 46% for everyday life skills, 37% for work skills, and 25% for interpersonal relationships.

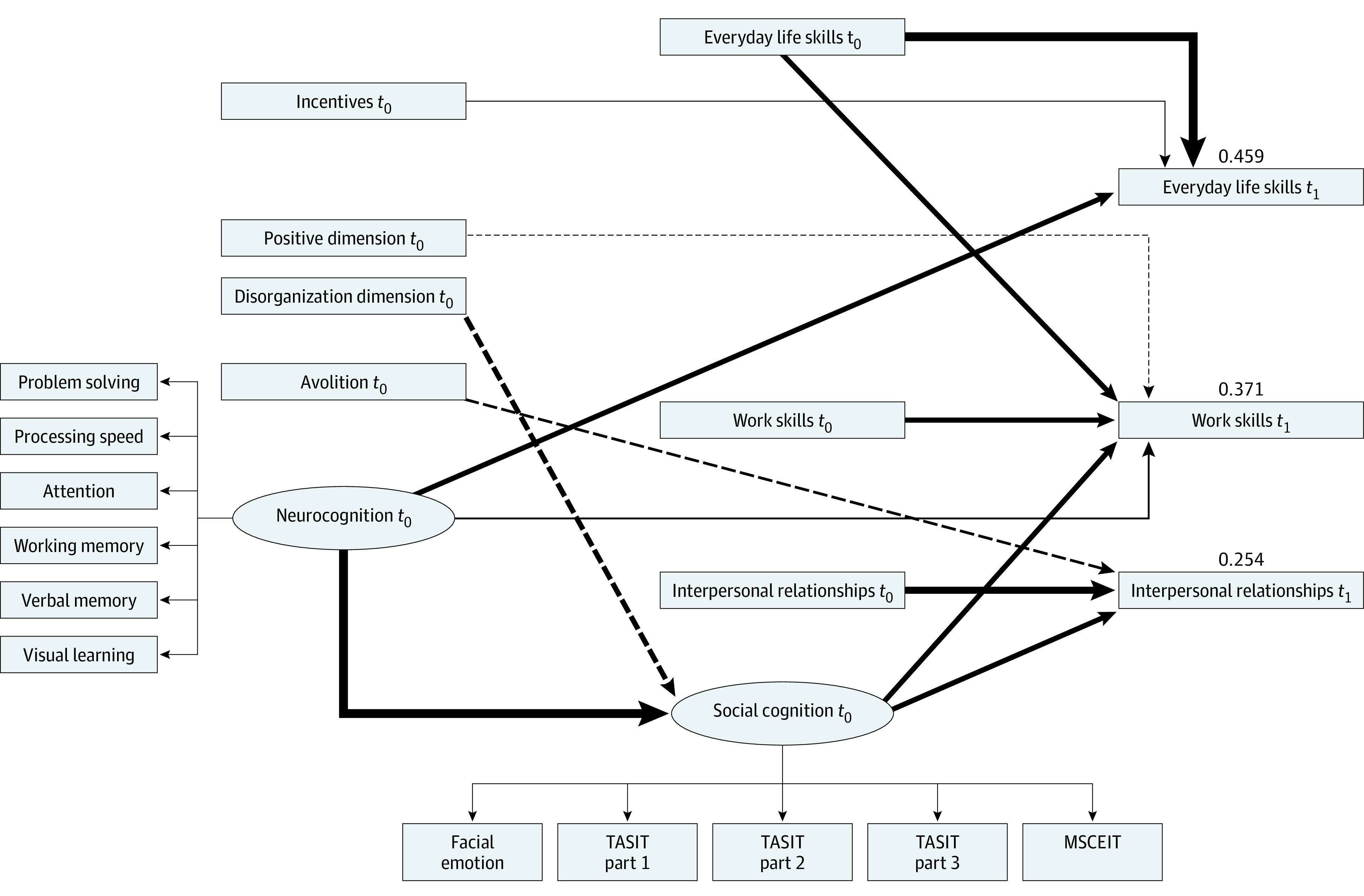

The Figure represents the final structural equation model. Only the association of baseline variables with functioning at t1 (either direct or indirect) that were not mediated by baseline functioning (within t0 associations; eTable 3 and eTable 4 in Supplement 1) will be described here. Five baseline variables were directly associated with real-life functioning at follow-up (Figure; Table 2). Better baseline neurocognition was associated (directly and indirectly through social cognition) with better follow-up everyday life skills (standardized regression coefficient [β], 0.274; 95% CI, 0.207-0.341; P < .001), work skills (β, 0.101; 95% CI, 0.005-0.196; P = .04), and interpersonal functioning (β, 0.122; 95% CI, 0.073-0.171; P < .001). Social cognition was directly and positively associated with interpersonal functioning (β, 0.194; 95% CI, 0.121-0.268; P < .001) and work skills (β, 0.185; 95% CI, 0.088-0.283; P < .001) at follow-up. Avolition was directly and negatively associated with interpersonal functioning (β, −0.126; 95% CI, −0.190 to −0.062; P < .001), whereas the positive dimension was directly and negatively associated with work skills (β, −0.059; 95% CI, −0.112 to −0.006; P = .03). The number of available incentives was directly and positively associated with everyday life skills at follow-up (β, 0.065; 95% CI, 0.016-0.115; P = .01). Furthermore, higher disorganization weakly and only indirectly (through social cognition) was associated with worse interpersonal relationships (β, −0.041; 95% CI, −0.063 to −0.019; P < .001) and work skills (β, −0.039; 95% CI, −0.064 to −0.014; P = .002) at follow-up.

Figure. Factors Associated With Real-Life Functioning at Follow-up.

Final structural equation model. Ellipses represent latent variables; rectangles, observed variables; t0, baseline; and t1, follow-up. Solid lines denote positive associations; dashed lines, negative associations. Line thickness is proportional to the strength of the association. Numbers above each real-life functioning domain represent the variance explained by the model. Facial emotion indicates the Facial Emotion Identification Test; TASIT, The Awareness of Social Inference Test; and MSCEIT, Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test.

Table 2. Direct and Indirect Associations of Baseline Variables With 3 Real-Life Functioning Domains at Follow-up Estimated in the Final Structural Equation Model.

| Baseline variable | Real-life functioning domain at follow-up | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everyday life skills | Interpersonal relationships | Work skills | |||||||

| Direct | Indirect | Direct | Indirect | Direct | Indirect | ||||

| Neurocognition | |||||||||

| β (95% CI)a | 0.274 (0.207 to 0.341) | NS | NS | 0.122 (0.073 to 0.171) | 0.101 (0.005 to 0.196) | 0.116 (0.053 to 0.179) | |||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | .04 | <.001 | |||||

| Social cognition | |||||||||

| β (95% CI)a | NS | NS | 0.194 (0.121 to 0.268) | NS | 0.185 (0.088 to 0.283) | NS | |||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | |||||||

| Avolition | |||||||||

| β (95% CI)a | NS | NS | −0.126 (−0.190 to −0.062) | NS | NS | NS | |||

| P value | <.001 | ||||||||

| Disorganization dimension | |||||||||

| β (95% CI)a | NS | NS | NS | −0.041 (−0.063 to −0.019) | NS | −0.039 (−0.064 to −0.014) | |||

| P value | <.001 | .002 | |||||||

| Positive dimension | |||||||||

| β (95% CI)a | NS | NS | NS | NS | −0.059 (−0.112 to −0.006) | NS | |||

| P value | .03 | ||||||||

| No. of incentives | |||||||||

| β (95% CI)a | 0.065 (0.016 to 0.115) | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |||

| P value | .01 | ||||||||

| Everyday life skills | |||||||||

| β (95% CI)a | 0.513 (0.456 to 0.570) | NS | NS | NS | 0.204 (0.135 to 0.273) | NS | |||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | |||||||

| Interpersonal relationships | |||||||||

| β (95% CI)a | NS | NS | 0.350 (0.286 to 0.413) | NS | NS | NS | |||

| P value | <.001 | ||||||||

| Work skills | |||||||||

| β (95% CI)a | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.255 (0.193 to 0.317) | NS | |||

| P value | <.001 | ||||||||

Abbreviation: NS, not significant.

β represents standardized regression coefficient.

In each real-life functioning domain, functioning at t0 was positively associated with functioning at t1. In addition, higher baseline functioning in everyday life skills was associated with higher work skills at follow-up (standardized effect estimate, 0.204; P < .001). The results of control analyses for site effect and split sample cross-validation of the final structural equation model are reported in eAppendix 2, eTable 5, and eTable 6 in Supplement 1.

Multiple Regression Analyses

Multiple regression analyses indicated that all the independent variables included in the structural equation model were associated with the variability of functioning at follow-up, after controlling for baseline functioning. The presence of physical or psychiatric comorbidities was not associated with real-life functioning domains at follow-up. Standardized regression coefficients, 95% CIs, and P values are reported in eTable 7, eTable 8, and eTable 9 in Supplement 1.

LCS Model

The final LCS model showed a satisfactory fit to the data (comparative fit index, 0.941; Tucker-Lewis index, 0.930; RMSEA, 0.046). The explained variance was higher for the latent change of work skills (R2 = 0.371) and interpersonal relationships (R2 = 0.327) than for everyday life skills (R2 = 0.195). Parameters for the LCS and all standardized regression coefficients are reported in Table 3. Parameters for the initial LCS model are reported in eTable 10 in Supplement 1.

Table 3. Association of Baseline Variables With Estimated Latent Change Scores From Baseline to 4-Year Follow-up in the Final Latent Change Score Model.

| Baseline measure | Estimated latent change score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ∆Everyday life skills | ∆Interpersonal relationships | ∆Work skills | ∆Social cognition | ∆Functional capacity | |

| Estimated change | 14.232 | 11.507 | 1.931 | 8.209 | −1.594 |

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | .226 | <.001 | .649 |

| Explained variance R2 of the latent change | 0.195 | 0.327 | 0.371 | 0.155 | 0.243 |

| Avolition | |||||

| Standardized regression coefficient (95% CI) | −0.088 (−0.127 to −0.049) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | ||||

| Positive dimension | |||||

| Standardized regression coefficient (95% CI) | −0.072 (−0.137 to 0.006) | ||||

| P value | .03 | ||||

| Neurocognition | |||||

| Standardized regression coefficient (95% CI) | 0.370 (0.253 to 0.486) | 0.102 (0.016 to 0.188) | 0.133 (0.015 to 0.250) | 1.138 (0.807 to 1.469) | |

| P value | <.001 | .02 | .03 | <.001 | |

| Social cognition | |||||

| Standardized regression coefficient (95% CI) | 0.140 (0.069 to 0.212) | 0.168 (0.075 to 0.261) | −0.262 (−0.401 to −0.122) | ||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Functional capacity | |||||

| Standardized regression coefficient (95% CI) | −0.585 (−0.672 to −0.498) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | ||||

| Everyday life skills | |||||

| Standardized regression coefficient (95% CI) | −0.462 (−0.543 to −0.381) | 0.121 (0.077 to 0.166) | 0.508 (0.331 to 0.685) | ||

| P value | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||

| Interpersonal relationships | |||||

| Standardized regression coefficient (95% CI) | −0.678 (−0.750 to −0.605) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | ||||

| Work skills | |||||

| Standardized regression coefficient (95% CI) | −0.736 (−0.803 to −0.669) | ||||

| P value | <.001 | ||||

Abbreviation: ∆, estimated change.

Higher baseline neurocognitive functioning was associated (as measured in the model by standardized regression coefficients) with positive change in everyday life skills (0.370; 95% CI, 0.253-0.486; P < .001). The model also showed that higher neurocognitive abilities at t0 were associated with a positive change in work skills (0.102; 95% CI, 0.016-0.188; P = .02), social cognition (0.133; 95% CI, 0.015-0.250; P = .03), and functional capacity (1.138; 95% CI, 0.807-1.469; P < .001) at follow-up. Better baseline social cognition was associated with favorable changes in interpersonal functioning (0.140; 95% CI, 0.069-0.212; P < .001) and work skills (0.168; 95% CI, 0.075-0.261; P < .001). Lower severity of avolition was associated with positive change in interpersonal relationships (−0.088; 95% CI, −0.127 to −0.049; P < .001), whereas lower scores on the positive dimension were associated with positive change in work skills (−0.072; 95% CI, −0.137 to 0.006; P = .03). Better baseline everyday life skills were associated with positive change in functional capacity (0.508; 95% CI, 0.331-0.685; P < .001) and work skills (0.121; 95% CI, 0.077-0.166; P < .001) at follow-up.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first prospective study including a broad range of variables (ie, illness-related variables, personal resources, and context-related factors) that used state-of-the-art assessment instruments to identify factors associated with functional outcome in a large sample of community-dwelling persons with schizophrenia. According to the structural equation model findings, 5 baseline variables (ie, neurocognition, social cognition, positive symptoms, avolition, and available incentives) were directly associated with at least 1 domain of real-life functioning at follow-up beyond their association (either direct or indirect) with baseline functioning. In particular, neurocognition was associated with everyday life and work skills; social cognition with work skills and interpersonal functioning; positive symptoms were weakly associated with work skills; avolition with interpersonal relationships; and the number of available incentives with everyday life skills.

Neurocognition was by far the variable with the strongest association with the everyday life skills domain of functioning, which is crucial for independent living and for reducing the burden on families and society. The association between avolition and real-life functioning was limited to interpersonal relationships, but for this domain, avolition showed an association stronger than that observed for neurocognition and comparable to that of social cognition.

Although associated with the other 2 domains of real-life functioning (work skills and everyday life activities) at baseline, avolition was not associated with functioning in those domains at follow-up. This result was unexpected because avolition is often regarded as the negative symptom domain with the strongest association with real-life functioning.3,9,29 However, it has to be considered that previous studies,9,30,31,32 in which negative symptoms outweighed cognitive dysfunction as determinants of real-life functioning, did not examine the different domains of functioning, as we did in the present study, or included a selected subgroup of persons with schizophrenia, such as those with persistent and primary negative symptoms or treatment resistance, who might differ from other persons with schizophrenia in terms of functional outcome and variables associated with it. Furthermore, none of those studies included social cognition.

The number of available incentives was the only variable showing an association with everyday life skills in the opposite direction at follow-up compared with baseline.3 In fact, a higher number of incentives was negatively associated with everyday life skills at baseline and positively associated at follow-up. This suggests that patients who function better are more able to keep incentives (eg, access to family practical and financial support, or registration in the unemployment list) over time. However, this was the only variable with an association that was not retained in control analyses.

A sixth variable, the disorganization dimension, was weakly and indirectly (through social cognition) associated with interpersonal and work functioning at t1. Differently from the other 2 psychopathological dimensions (ie, avolition and positive symptoms), disorganization dimension was not directly associated with follow-up functioning.

In a population of community-dwelling persons with chronic schizophrenia, changes after 4 years are not expected to be large; however, a certain degree of variability is expected, with some persons improving, others deteriorating, and others showing no significant change. When looking at factors associated with changes using the LCS model, neurocognition and social cognition confirmed their roles as important factors associated with improvement or deterioration of real-life functioning over time. According to the LCS model, persons with better neurocognitive functioning at baseline were more likely to improve in everyday life and work skills at follow-up. Baseline neurocognition was also associated with the likelihood of change in social cognition, which in turn appeared to be associated with changes in work skills and interpersonal relationships. The association of avolition at t0 with changes in interpersonal functioning at follow-up was as strong as that of social cognition, whereas positive symptoms were weakly associated with changes in work skills.

In the LCS model, changes in work skills were also associated with baseline everyday life skills; persons with a greater ability to cope with everyday life demands (eg, use of public transportation, management of personal finances, and recognizing and avoiding common dangers) were more likely to cope with work activity demands at follow-up. Baseline everyday life skills, together with neurocognition, were associated with changes in functional capacity at follow-up.

Strengths and Limitations

In light of the differences between the 2 methods of analysis (ie, structural equation model and LCS modeling), similarities in longitudinal findings should be regarded as a strength of our study. Furthermore, the LCS model provided unique information by showing the association of baseline neurocognition with social cognition and functional capacity changes. Multiple regression analyses supported the structural equation model findings, showing that all the independent variables included in that model accounted for the variability of functioning at follow-up, whereas the presence of physical or psychiatric comorbidities had no significant association with follow-up real-life functioning.

Our study has some limitations that should be considered. We used latent variables for both neurocognition and social cognition and could not determine whether individual cognitive domains were differentially associated with functioning. Our results will require external independent validation.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our large prospective study in persons with schizophrenia living in the community indicates that the variables associated with functional outcome at follow-up include some domains that are not systematically assessed and targeted by therapeutic interventions in community mental health services (ie, neurocognition, social cognition, avolition, and practical skills to cope with everyday life demands). These findings suggest that a change in mental health care provision is necessary. People with schizophrenia, even in advanced stages of the disorder, require a detailed assessment of their psychopathological and functional characteristics. If data relevant to the individual characteristics in all mentioned domains are available, then personalized and integrated management programs can be implemented, their impact can be constantly monitored, and changes to ongoing programs can be introduced to meet new or still unmet needs. The key roles of social and nonsocial cognition (which, as shown by our data, are associated with different domains of real-life functioning) and of practical skills to meet the demands of everyday life strongly support the adoption of cognitive training interventions in routine mental health care, in particular those with a focus on the transfer of cognitive skills to real-life functioning,56,57 combined with personalized psychosocial interventions aimed to promote independent living.

eAppendix 1. Methods

eAppendix 2. Results of Control Analyses

eTable 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population at Baseline (N = 618)

eTable 2. Within-Subject Comparisons of Follow-up Versus Baseline Characteristics

eTable 3. Initial Structural Equation Model (SEM)

eTable 4. Direct and Indirect Effects of Baseline Variables on the Three Real-Life Functioning Domains at t0 (Within t0 Effects) Estimated in the Final Structural Equation Model

eTable 5. Split Sample Cross-Validation of the Final Structural Equation Model (SEM): Standardized Coefficients of the Effects of Baseline Variables on the Three Real-Life Functioning Domains at Follow-up in the Training and Test Samples

eTable 6. Control Analysis for the Site Effect

eTable 7. Multiple Linear Regression of Work Skills at Follow-up on Variables Used in the Structural Equation Model and Physical and Psychiatric Comorbidities

eTable 8. Multiple Linear Regression of Everyday Life Skills at Follow-up on Variables Used in the Structural Equation Model and Physical and Psychiatric Comorbidities

eTable 9. Multiple Linear Regression of Interpersonal Relationships at Follow-up on Variables Used in the Structural Equation Model and Physical and Psychiatric Comorbidities

eTable 10. Initial Latent Change Score Model

eReferences.

Nonauthors Collaborators. Italian Network for Research on Psychoses members

References

- 1.Zipursky RB, Agid O. Recovery, not progressive deterioration, should be the expectation in schizophrenia. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(1):94-96. doi: 10.1002/wps.20194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jääskeläinen E, Juola P, Hirvonen N, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2013;39(6):1296-1306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbs130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galderisi S, Rossi A, Rocca P, et al. ; Italian Network For Research on Psychoses . The influence of illness-related variables, personal resources and context-related factors on real-life functioning of people with schizophrenia. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):275-287. doi: 10.1002/wps.20167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fleischhacker WW, Arango C, Arteel P, et al. Schizophrenia—time to commit to policy change. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(S3)(suppl 3):S165-S194. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbu006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rossi A, Amore M, Galderisi S, et al. ; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses . The complex relationship between self-reported “personal recovery” and clinical recovery in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2018;192(1):108-112. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2017.04.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlson FJ, Ferrari AJ, Santomauro DF, et al. Global epidemiology and burden of schizophrenia: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Schizophr Bull. 2018;44(6):1195-1203. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sby058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Emsley R, Chiliza B, Schoeman R. Predictors of long-term outcome in schizophrenia. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21(2):173-177. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f33f76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harvey PD, Strassnig M. Predicting the severity of everyday functional disability in people with schizophrenia: cognitive deficits, functional capacity, symptoms, and health status. World Psychiatry. 2012;11(2):73-79. doi: 10.1016/j.wpsyc.2012.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galderisi S, Bucci P, Mucci A, et al. Categorical and dimensional approaches to negative symptoms of schizophrenia: focus on long-term stability and functional outcome. Schizophr Res. 2013;147(1):157-162. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2013.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galderisi S, Rossi A, Rocca P, et al. ; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses . Pathways to functional outcome in subjects with schizophrenia living in the community and their unaffected first-degree relatives. Schizophr Res. 2016;175(1-3):154-160. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.04.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galderisi S, Rucci P, Kirkpatrick B, et al. ; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses . Interplay among psychopathologic variables, personal resources, context-related factors, and real-life functioning in individuals with schizophrenia: a network analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):396-404. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Green MF, Llerena K, Kern RS. The “right stuff” revisited: what have we learned about the determinants of daily functioning in schizophrenia? Schizophr Bull. 2015;41(4):781-785. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbv018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Strassnig MT, Raykov T, O’Gorman C, et al. Determinants of different aspects of everyday outcome in schizophrenia: the roles of negative symptoms, cognition, and functional capacity. Schizophr Res. 2015;165(1):76-82. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green MF, Horan WP, Lee J. Nonsocial and social cognition in schizophrenia: current evidence and future directions. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(2):146-161. doi: 10.1002/wps.20624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bowie CR, Leung WW, Reichenberg A, et al. Predicting schizophrenia patients’ real-world behavior with specific neuropsychological and functional capacity measures. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63(5):505-511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bowie CR, Depp C, McGrath JA, et al. Prediction of real-world functional disability in chronic mental disorders: a comparison of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(9):1116-1124. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowie CR, Reichenberg A, Patterson TL, Heaton RK, Harvey PD. Determinants of real-world functional performance in schizophrenia subjects: correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):418-425. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lepage M, Bodnar M, Bowie CR. Neurocognition: clinical and functional outcomes in schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry. 2014;59(1):5-12. doi: 10.1177/070674371405900103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Strassnig M, Kotov R, Fochtmann L, Kalin M, Bromet EJ, Harvey PD. Associations of independent living and labor force participation with impairment indicators in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder at 20-year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2018;197(1):150-155. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fett AK, Viechtbauer W, Dominguez MD, Penn DL, van Os J, Krabbendam L. The relationship between neurocognition and social cognition with functional outcomes in schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35(3):573-588. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2010.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman JI, Harvey PD, McGurk SR, et al. Correlates of change in functional status of institutionalized geriatric schizophrenic patients: focus on medical comorbidity. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1388-1394. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gold JM, Goldberg RW, McNary SW, Dixon LB, Lehman AF. Cognitive correlates of job tenure among patients with severe mental illness. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1395-1402. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stirling J, White C, Lewis S, et al. Neurocognitive function and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: a 10-year follow-up of an epidemiological cohort. Schizophr Res. 2003;65(2-3):75-86. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(03)00014-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robinson DG, Woerner MG, McMeniman M, Mendelowitz A, Bilder RM. Symptomatic and functional recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(3):473-479. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reichenberg A, Feo C, Prestia D, Bowie CR, Patterson TL, Harvey PD. The course and correlates of everyday functioning in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res Cogn. 2014;1(1):e47-e52. doi: 10.1016/j.scog.2014.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Horan WP, Green MF, DeGroot M, et al. Social cognition in schizophrenia, part 2: 12-month stability and prediction of functional outcome in first-episode patients. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(4):865-872. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCleery A, Lee J, Fiske AP, et al. Longitudinal stability of social cognition in schizophrenia: a 5-year follow-up of social perception and emotion processing. Schizophr Res. 2016;176(2-3):467-472. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rocca P, Galderisi S, Rossi A, et al. ; Members of the Italian Network for Research on Psychoses . Disorganization and real-world functioning in schizophrenia: results from the multicenter study of the Italian Network for Research on Psychoses. Schizophr Res. 2018;201(1):105-112. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2018.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mucci A, Merlotti E, Üçok A, Aleman A, Galderisi S. Primary and persistent negative symptoms: concepts, assessments and neurobiological bases. Schizophr Res. 2017;186(1):19-28. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.05.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galderisi S, Mucci A, Bitter I, et al. ; Eufest Study Group . Persistent negative symptoms in first episode patients with schizophrenia: results from the European First Episode Schizophrenia Trial. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23(3):196-204. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2012.04.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chang WC, Hui CL, Chan SK, Lee EH, Chen EY. Impact of avolition and cognitive impairment on functional outcome in first-episode schizophrenia-spectrum disorder: a prospective one-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res. 2016;170(2-3):318-321. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ahmed AO, Murphy CF, Latoussakis V, et al. An examination of neurocognition and symptoms as predictors of post-hospital community tenure in treatment resistant schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 2016;236(1):47-52. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anda L, Brønnick KS, Johnsen E, Kroken RA, Jørgensen H, Løberg EM. The course of neurocognitive changes in acute psychosis: relation to symptomatic improvement. PLoS One. 2016;11(12):e0167390. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0167390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bergh S, Hjorthøj C, Sørensen HJ, et al. Predictors and longitudinal course of cognitive functioning in schizophrenia spectrum disorders, 10 years after baseline: the OPUS study. Schizophr Res. 2016;175(1-3):57-63. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2016.03.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Galderisi S, Rucci P, Mucci A, et al. ; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses . The interplay among psychopathology, personal resources, context-related factors and real-life functioning in schizophrenia: stability in relationships after 4 years and differences in network structure between recovered and non-recovered patients. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(1):81-91. doi: 10.1002/wps.20700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Patient Edition (SCID-I/P). Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261-276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallwork RS, Fortgang R, Hashimoto R, Weinberger DR, Dickinson D. Searching for a consensus five-factor model of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale for schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2012;137(1-3):246-250. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.01.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kirkpatrick B, Strauss GP, Nguyen L, et al. The Brief Negative Symptom Scale: psychometric properties. Schizophr Bull. 2011;37(2):300-305. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mucci A, Galderisi S, Merlotti E, et al. ; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses . The Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS): independent validation in a large sample of Italian patients with schizophrenia. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(5):641-647. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2015.01.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E. Assessing depression in schizophrenia: the Calgary Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1993;163(22):39-44. doi: 10.1192/S0007125000292581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gerlach J, Korsgaard S, Clemmesen P, et al. The St. Hans Rating Scale for extrapyramidal syndromes: reliability and validity. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;87(4):244-252. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03366.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, Kern RS, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 1: test selection, reliability, and validity. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):203-213. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kern RS, Nuechterlein KH, Green MF, et al. The MATRICS Consensus Cognitive Battery, part 2: co-norming and standardization. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(2):214-220. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07010043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerr SL, Neale JM. Emotion perception in schizophrenia: specific deficit or further evidence of generalized poor performance? J Abnorm Psychol. 1993;102(2):312-318. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.102.2.312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McDonald S, Bornhofen C, Shum D, Long E, Saunders C, Neulinger K. Reliability and validity of The Awareness of Social Inference Test (TASIT): a clinical test of social perception. Disabil Rehabil. 2006;28(24):1529-1542. doi: 10.1080/09638280600646185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.State of Illinois Department of Human Services . Specific Level of Functioning Assessment and Physical Health Inventory: IL462-1215 (R-9-08). Accessed January 2012. https://www.dhs.state.il.us/onenetlibrary/12/documents/Forms/IL462-1215.pdf

- 49.Friborg O, Hjemdal O, Rosenvinge JH, Martinussen M. A new rating scale for adult resilience: what are the central protective resources behind healthy adjustment? Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12(2):65-76. doi: 10.1002/mpr.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tait L, Birchwood M, Trower P. A new scale (SES) to measure engagement with community mental health services. J Ment Health. 2002;11(2):191-198. doi: 10.1080/09638230020023570-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ritsher JB, Otilingam PG, Grajales M. Internalized stigma of mental illness: psychometric properties of a new measure. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121(1):31-49. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2003.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mausbach BT, Harvey PD, Goldman SR, Jeste DV, Patterson TL. Development of a brief scale of everyday functioning in persons with serious mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(6):1364-1372. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbm014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mucci A, Rucci P, Rocca P, et al. ; Italian Network for Research on Psychoses . The Specific Level of Functioning Scale: construct validity, internal consistency and factor structure in a large Italian sample of people with schizophrenia living in the community. Schizophr Res. 2014;159(1):144-150. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2014.07.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosseel Y. Iavaan: an R package for Structural Equation Modeling. J Stat Softw. 2012;48(2):1-36. doi: 10.18637/jss.v048.i02 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kievit RA, Brandmaier AM, Ziegler G, et al. ; NSPN Consortium . Developmental cognitive neuroscience using latent change score models: a tutorial and applications. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;33(1):99-117. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wykes T, Huddy V, Cellard C, McGurk SR, Czobor P. A meta-analysis of cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: methodology and effect sizes. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(5):472-485. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10060855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bowie CR, Bell MD, Fiszdon JM, et al. Cognitive remediation for schizophrenia: an expert working group white paper on core techniques. Schizophr Res. 2020;215(1):49-53. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2019.10.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eAppendix 1. Methods

eAppendix 2. Results of Control Analyses

eTable 1. Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of the Study Population at Baseline (N = 618)

eTable 2. Within-Subject Comparisons of Follow-up Versus Baseline Characteristics

eTable 3. Initial Structural Equation Model (SEM)

eTable 4. Direct and Indirect Effects of Baseline Variables on the Three Real-Life Functioning Domains at t0 (Within t0 Effects) Estimated in the Final Structural Equation Model

eTable 5. Split Sample Cross-Validation of the Final Structural Equation Model (SEM): Standardized Coefficients of the Effects of Baseline Variables on the Three Real-Life Functioning Domains at Follow-up in the Training and Test Samples

eTable 6. Control Analysis for the Site Effect

eTable 7. Multiple Linear Regression of Work Skills at Follow-up on Variables Used in the Structural Equation Model and Physical and Psychiatric Comorbidities

eTable 8. Multiple Linear Regression of Everyday Life Skills at Follow-up on Variables Used in the Structural Equation Model and Physical and Psychiatric Comorbidities

eTable 9. Multiple Linear Regression of Interpersonal Relationships at Follow-up on Variables Used in the Structural Equation Model and Physical and Psychiatric Comorbidities

eTable 10. Initial Latent Change Score Model

eReferences.

Nonauthors Collaborators. Italian Network for Research on Psychoses members