Key Points

Question

From 2010 to 2017, for hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of heart failure (HF), what were the national trends of overall hospitalizations, unique patient hospitalizations, and readmissions based on the number of visits in a given year?

Findings

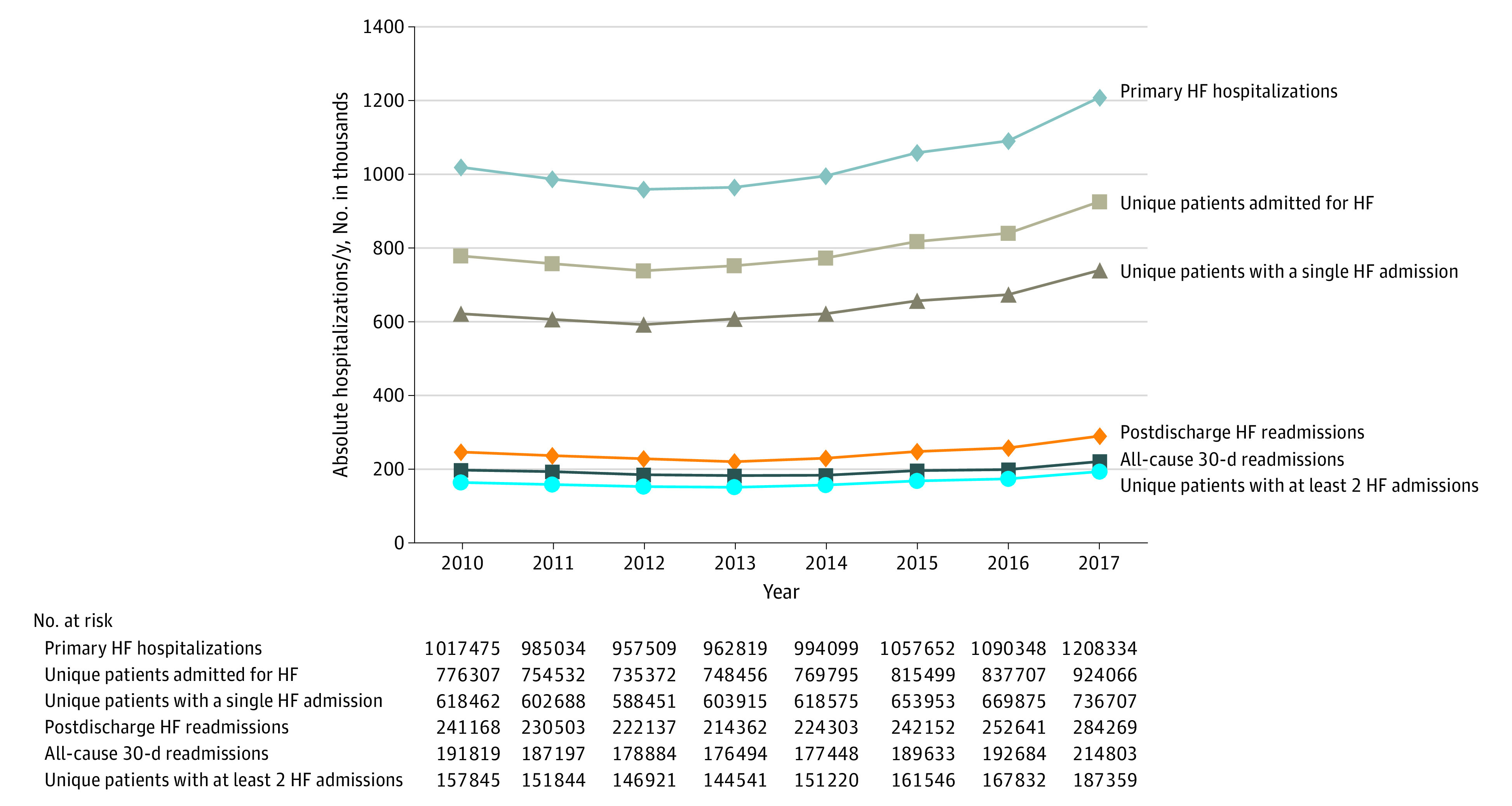

This cohort study of 8 273 270 HF hospital admissions from January 2010 to December 2017 showed that the rates for overall hospitalization, unique patient hospitalizations, and postdischarge HF readmissions declined between 2010 and 2014, followed by an increase between 2014 and 2017.

Meaning

Per this analysis, national HF hospitalizations (overall hospitalizations, unique hospitalizations, and readmissions) have been increasing from 2014 onwards.

This cohort study examines contemporary overall and sex-specific trends of overall HF hospitalizations, unique patient HF hospitalizations, and HF readmissions in a large national US administrative database from 2010 to 2017.

Abstract

Importance

Previous studies have described the secular trends of overall heart failure (HF) hospitalizations, but the literature describing the national trends of unique index hospitalizations and readmission visits for the primary management of HF is lacking.

Objectives

To examine contemporary overall and sex-specific trends of unique primary HF (grouped by number of visits for the same patient in a given year) and 30-day readmission visits in a large national US administrative database from 2010 to 2017.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This cohort study used data from all adult hospitalizations in the Nationwide Readmission Database from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2017, with a primary diagnosis of HF. Data analyses were conducted from March to November 2020.

Exposures

Admission for a primary diagnosis of HF at discharge.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Unique and overall hospitalizations with a primary diagnosis of HF and postdischarge readmissions. Unique primary HF hospitalizations were grouped by number of visits for the same patient in a given year.

Results

There were 8 273 270 primary HF hospitalizations with a single primary HF admission present in 5 092 626 unique patients, and 1 269 109 had 2 or more HF hospitalizations. The mean age was 72.1 (95% CI, 72.0-72.3) years, and 48.9% (95% CI, 48.7-49.0) were women. The primary HF hospitalization rates per 1000 US adults declined from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013 and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017. The rates per 1000 US adults for postdischarge HF readmissions (1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017) had similar trends.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this analysis of a nationally representative administrative data set, for primary HF admissions, crude rates of overall and unique patient hospitalizations declined from 2010 to 2014 followed by an increase from 2014 to 2017. Additionally, readmission visits after index HF hospitalizations followed a similar trend. Future studies are needed to verify these findings to improve policies for HF management.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) is one of the leading causes for hospital admission in the US, accounting for almost 6.5 million hospital days annually.1 HF hospitalizations are at high risk of readmission, and such cumulative events are a strong predictor of mortality.2 Previous studies have described the secular trends of overall HF hospitalizations, but the literature describing the national trends of unique index hospitalizations and readmission visits for the primary management of HF is lacking.3,4,5,6,7,8,9 Hence, we examined contemporary overall and sex-specific trends of unique primary HF hospitalization and 30-day readmission visits in a large national US administrative database from 2010 to 2017.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective analysis using a survey analysis technique of the Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD) to study the trends of HF hospitalizations and readmissions, as done previously.10,11,12,13,14 The NRD is a publicly available all-payer database developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality for the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. The NRD provides accurate representation of total US hospitalizations and readmissions visits regardless of insurance provider. We identified all adult (17 years or older) hospitalizations from January 1, 2010, to December 31, 2017, with an HF discharge diagnosis in the primary or secondary diagnosis field. HF was defined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) and ICD-10-CM codes (ICD-10-CM codes I50.1 to I50.9, I11.0, I13.0, and I13.2; ICD-9-CM codes 428, 398.91, 402.01, 402.11, 402.91, 404.01, 404.03, 404.11, 404.13, 404.91, and 404.93). A primary HF hospitalization was defined as any ICD-9-CM or ICD-10-CM HF discharge code used as the primary designated diagnostic code. The NRD uses unique identifiers by patient to account for readmissions within a given year. We used unique deidentified information to calculate the number of primary HF hospitalizations for each patient within a given year. Given that data were taken from a publicly available, deidentified database, we obtained an institutional review board exemption from the University of California, Los Angeles.

We examined calendar-year changes in primary HF hospitalizations, including overall and unique patient visits (those with 1 visit only vs those with readmissions). The temporal trends of patient demographic characteristics (age, insurance, median household income national quartiles) and comorbidities, such as hypertension, hyperlipidemia, coronary artery disease, cerebrovascular disease, chronic pulmonary disease, and renal disease, were described for the overall cohort with a primary diagnosis of HF. The NRD does not include race/ethnicity data for hospitalizations. Then, we described the trends of crude hospitalization rates per 1000 US adults for both sexes and sex-specific population. US Census estimates for each year were used for both sexes and then individual sex groups to calculate crude rates per 1000 persons.

We also additionally performed analyses to study the trends of hospitalizations with primary or secondary diagnoses of HF, trends of all-cause 30-day readmission visits, and trends of postdischarge HF readmissions. The NRD cannot be used to study readmissions across different data years; hence, visits during December were not included for 30-day readmission analysis. All analyses were performed in Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp).

Results

Between 2010 and 2017 in the US, there were 35 197 725 (unweighted, 16 516 357) hospitalizations with a primary or secondary diagnosis of HF and 8 273 270 primary HF hospitalizations. A single primary HF admission occurred in 5 092 626 unique patients, and 1 269 109 had 2 or more HF hospitalization (Figure). The mean age was 72.1 (95% CI, 72.0-72.3) years, and 48.9% (95% CI, 48.7-49.0) were women. The hospitalization rates per 1000 US adults for overall cohort changed from 4.4 in 2010 to 4.1 in 2013 and then increased from 4.2 in 2014 to 4.9 in 2017 (Table 1). Similar trends were observed for unique primary HF patient visits and those with no or at least 1 readmission for HF management when data were analyzed for overall and sex-specific populations (Table 1).

Figure. US Trends for Overall Heart Failure (HF) Hospitalizations, Unique Patient Visits, and Postdischarge HF Readmissions .

Table 1. Trends of Crude Rates of Primary Heart Failure (HF) Hospitalizations Overall and By Sex.

| Measure | Year, rate per 1000 US adults | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Whole cohort | ||||||||

| Primary HF hospitalizations | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.5 | 4.9 |

| Unique patients admitted for HF | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.4 | 3.8 |

| Unique patients with a single HF admission in a given year | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.7 | 3.0 |

| Unique patients with ≥2 HF admissions in a given year | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Postdischarge HF readmissions | 1.0 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| All-cause 30-d readmissions | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| Primary or secondary HF hospitalizations | 18.0 | 17.9 | 17.5 | 17.5 | 17.8 | 18.8 | 19.2 | 21.0 |

| Male subgroup | ||||||||

| Primary HF hospitalizations | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.4 | 4.7 | 4.8 | 5.3 |

| Unique patients admitted for HF | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.6 | 3.6 | 4.0 |

| Unique patients with a single HF admission in a given year | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.7 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.2 |

| Unique patients with ≥2 HF admissions in a given year | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| Female subgroup | ||||||||

| Primary HF hospitalizations | 4.3 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 3.8 | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.2 | 4.5 |

| Unique patients admitted for HF | 3.2 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.7 |

| Unique patients with a single HF admission in a given year | 2.7 | 2.6 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.8 |

| Unique patients with ≥2 HF admissions in a given year | 0.7 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.6 | 0.7 |

The mean (SD) age of patients decreased from 72.5 (13.4) years in 2010 to 71.6 (15.4) years in 2017, the proportion of females decreased (50.3% [95% CI, 49.7-50.8] in 2010 to 47.9% [95% CI, 47.6-48.1] in 2017), and documented rates of comorbid conditions increased (Table 2) (eTables 1 and 2 in the Supplement). The hospitalization rates per 1000 US adults for those with primary or secondary diagnosis of HF changed from 18.0 in 2010 to 17.8 in 2014 and then increased to 21.0 in 2017 (Table 1). The rates per 1000 US adults for postdischarge HF readmissions (1.0 in 2010 to 0.9 in 2014 to 1.1 in 2017) and all-cause 30-day readmissions (0.8 in 2010 to 0.7 in 2014 to 0.9 in 2017) had similar trends (Table 1).

Table 2. Trends of Patient Demographic Characteristics and Comorbidities From 2010 to 2017 for Primary Heart Failure Hospitalizations.

| Characteristic | Year, % (95% CI) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |

| Total No. | 1 017 475 | 985 034 | 957 509 | 962 819 | 994 099 | 1 057 652 | 1 090 348 | 1 208 334 |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 72.5 (13.4) | 72.5 (13.4) | 72.4 (13.3) | 72.3 (13.9) | 72.2 (14.2) | 72.0 (15.2) | 71.7 (15.2) | 71.6 (15.4) |

| Female | 50.3 (49.7-50.8) | 49.9 (49.4-50.5) | 49.4 (48.9-49.9) | 48.8 (48.4-49.1) | 48.6 (48.2-48.9) | 48.3 (48.0-48.6) | 48.3 (48.0-48.6) | 47.9 (47.6-48.1) |

| Payer status | ||||||||

| Medicare | 75.8 (74.9-76.8) | 76.2 (75.2-77.0) | 76.3 (75.3-77.3) | 76.1 (75.3-76.8) | 75.7 (74.9-76.5) | 75.5 (74.8-76.2) | 75.2 (74.5-76.0) | 75.6 (75.0-76.2) |

| Medicaid | 8.2 (7.6-8.7) | 8.2 (7.6-8.8) | 8.1 (7.6-8.8) | 8.3 (7.8-8.8) | 9.4 (8.9-10.0) | 9.7 (9.2-10.2) | 10.3 (9.8-10.8) | 10.2 (9.8-10.7) |

| Private | 10.9 (10.5-11.4) | 10.5 (10.1-11.0) | 10.1 (9.7-10.7) | 9.9 (9.5-10.4) | 10.1 (9.7-10.5) | 10.2 (9.8-10.7) | 10.0 (9.6-10.3) | 9.8 (9.5-10.1) |

| Self-pay | 2.8 (2.6-3.1) | 2.7 (2.5-3.0) | 2.8 (2.5-3.1) | 3.0 (2.9-3.3) | 2.6 (2.4-2.8) | 2.4 (2.1-2.6) | 2.2 (2.1-2.5) | 2.2 (2.0-2.3) |

| No-charge | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) | 0.3 (0.2-0.3) | 0.4 (0.3-0.5) | 0.3 (0.3-0.5) | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) | 0.3 (0.2-0.4) | 0.3 (0.2-0.3) |

| Other | 2.0 (1.8-2.2) | 2.1 (1.9-2.4) | 2.4 (2.1-2.6) | 2.3 (2.1-2.5) | 1.9 (1.7-2.1) | 1.9 (1.7-2.1) | 2.0 (1.7-2.3) | 1.9 (1.8-2.1) |

| Median household income quartile | ||||||||

| 1st | 36.0 (34.0-38.0) | 36.7 (34.7-38.7) | 36.5 (34.6-38.5) | 32.9 (31.2-34.5) | 32.4 (30.8-34.1) | 34.9 (33.3-36.6) | 34.5 (32.9-36.2) | 34.9 (33.9-36.4) |

| 2nd | 24.7 (23.5-25.9) | 24.0 (22.8-25.1) | 24.3 (23.2-25.4) | 27.1 (26.1-28.2) | 27.3 (26.3-28.4) | 25.2 (24.2-26.2) | 26.1 (25.1-27.2) | 27.8 (26.9-28.8) |

| 3rd | 21.4 (20.2-22.6) | 22.4 (21.3-23.6) | 21.4 (20.3-22.5) | 22.4 (21.5-23.4) | 21.7 (20.8-22.7) | 22.9 (21.9-23.9) | 23.1 (22.1-24.1) | 21.9 (21.0-22.9) |

| 4th | 17.9 (16.5-19.4) | 16.9 (15.5-18.5) | 17.8 (16.3-19.3) | 17.6 (16.2-19.0) | 18.6 (17.1-20.0) | 17.0 (15.7-18.4) | 16.3 (15.0-17.6) | 15.4 (14.3-16.5) |

| Comorbidities | ||||||||

| Hypertension | 76.5 (75.9-77.1) | 77.5 (76.9-78.1) | 78.7 (78.0-79.3) | 79.6 (79.0-80.2) | 81.3 (80.8-81.9) | 83.4 (82.9-83.8) | 86.6 (86.1-87.0) | 91.4 (91.1-91.7) |

| Diabetes | 44.9 (44.4-45.5) | 45.2 (44.7-45.7) | 45.5 (45.0-46.1) | 46.3 (45.9-46.7) | 47.2 (46.8-47.7) | 47.6 (47.2-48.0) | 47.1 (46.6-47.6) | 48.9 (48.4-49.3) |

| Lipid disorders | 40.4 (39.5-41.3) | 42.1 (41.2-43.0) | 43.7 (42.8-44.7) | 46.2 (45.4-47.0) | 48.2 (47.4-49.0) | 50.2 (49.5-50.9) | 51.6 (50.7-52.5) | 53.1 (52.4-53.9) |

| CAD | 54.3 (53.5-55.0) | 53.7 (52.9-54.4) | 54.1 (53.3-54.8) | 54.0 (53.4-54.7) | 54.0 (53.4-54.7) | 54.3 (53.7-54.8) | 54.1 (53.5-54.6) | 54.1 (53.6-54.7) |

| COPD | 29.7 (29.2-30.3) | 29.9 (29.3-30.4) | 30.3 (29.7-30.9) | 30.3 (29.8-30.7) | 30.2 (29.7-30.7) | 31.3 (30.9-31.8) | 34.7 (34.2-35.2) | 35.4 (35.0-35.9) |

| Renal disease | 45.9 (45.1-46.6) | 47.3 (46.6-48.1) | 48.9 (48.2-49.7) | 52.5 (51.9-53.1) | 54.4 (53.8-55.0) | 55.8 (55.3-56.3) | 57.7 (57.2-58.2) | 60.6 (60.1-61.0) |

Abbreviations: CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Discussion

In this nationally representative sample of hospital admissions in the US, we found that the crude rate of hospital admission primarily for HF declined from 2010 through 2014, similar to that reported previously.1,2 But interestingly, we observed an increase in the crude rate from 2014 to 2017. We also found that 30-day readmissions after HF index hospitalizations had a similar trend of decline between 2010 and 2014 followed by an increase from 2014 onwards.

The trends of HF hospitalizations and 30-day readmissions observed in our study until 2014 are parallel to several reports analyzing data from a similar timeline.3,5,8,9 Literature highlighting the trends after 2014 is limited.7 In contrast to our findings of an increase in crude rates from 2015 to 2017, a Veterans Administration study showed a decline in adjusted 30-day readmission risk.7 Our study provides descriptive analyses of national hospitalization utilization and does not risk adjust readmission risk. Additionally, the Veteran Administration population is predominantly male (approximately 98%), whereas approximately 51% of those included in this analysis were male. The increasing hospitalization rate in our study may represent an actual increase in HF hospitalizations or shifts in administrative coding practices, increased use of HF biomarkers, or lower thresholds for diagnosis of HF with preserved ejection fraction.6 We found notable sex differences in hospitalization, with higher rates for men compared with women.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The NRD does not identify unique patients across different years. The NRD is an administrative database, and clinical data, such as ejection fraction, are not available. Hence, we were not able to differentiate between HF with preserved ejection fraction and HF with reduced ejection fraction. The NRD does not include a patient’s race or ethnicity. The NRD develops random sampling strategies and survey weights to make accurate national epidemiologic inferences. Not all hospitalizations and readmissions are included in the database.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we found that for primary HF admissions at the US national level, crude rates of overall and unique patients declined from 2010 through 2014, followed by an increase from 2014 to 2017. Future studies are needed to verify our findings to better develop and improve individualized strategies for HF prevention, management, and surveillance for men and women.

eTable 1. Trends of patient demographics and comorbidities from 2010 to 2017 for unique patients with single primary heart failure hospitalizations.

eTable 2. Trends of patient demographics and comorbidities from 2010 to 2017 for unique patients with multiple primary heart failure hospitalizations.

References

- 1.Ziaeian B, Fonarow GC. The prevention of hospital readmissions in heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2016;58(4):379-385. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2015.09.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Setoguchi S, Stevenson LW, Schneeweiss S. Repeated hospitalizations predict mortality in the community population with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2007;154(2):260-266. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2007.01.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akintoye E, Briasoulis A, Egbe A, et al. National trends in admission and in-hospital mortality of patients with heart failure in the United States (2001-2014). J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(12):e006955. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006955 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blecker S, Herrin J, Li L, Yu H, Grady JN, Horwitz LI. Trends in hospital readmission of Medicare-covered patients with heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(9):1004-1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergethon KE, Ju C, DeVore AD, et al. Trends in 30-day readmission rates for patients hospitalized with heart failure: findings from the Get With The Guidelines–Heart Failure Registry. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9(6):e002594. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang PP, Wruck LM, Shahar E, et al. Trends in hospitalizations and survival of acute decompensated heart failure in four US communities (2005-2014): ARIC study community surveillance. Circulation. 2018;138(1):12-24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.027551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parizo JT, Kohsaka S, Sandhu AT, Patel J, Heidenreich PA. Trends in readmission and mortality rates following heart failure hospitalization in the Veterans Affairs health care system from 2007 to 2017. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(9):1042-1047. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vasan RS, Zuo Y, Kalesan B. Divergent temporal trends in morbidity and mortality related to heart failure and atrial fibrillation: age, sex, race, and geographic differences in the United States, 1991-2015. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(8):e010756. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J, Normand SL, Wang Y, Krumholz HM. National and regional trends in heart failure hospitalization and mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries, 1998-2008. JAMA. 2011;306(15):1669-1678. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferro EG, Secemsky EA, Wadhera RK, et al. Patient readmission rates for all insurance types after implementation of the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(4):585-593. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buhr RG, Jackson NJ, Kominski GF, Dubinett SM, Mangione CM, Ong MK. Readmission rates for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease under the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program: an interrupted time series analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(12):3581-3590. doi: 10.1007/s11606-020-05958-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agrawal S, Garg L, Shah M, et al. Thirty-day readmissions after left ventricular assist device implantation in the United States: insights from the Nationwide Readmissions Database. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(3):e004628. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shah M, Patel B, Tripathi B, et al. Hospital mortality and thirty day readmission among patients with non-acute myocardial infarction related cardiogenic shock. Int J Cardiol. 2018;270:60-67. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.06.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shah M, Patil S, Patel B, et al. Causes and predictors of 30-day readmission in patients with acute myocardial infarction and cardiogenic shock. Circ Heart Fail. 2018;11(4):e004310. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.117.004310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Trends of patient demographics and comorbidities from 2010 to 2017 for unique patients with single primary heart failure hospitalizations.

eTable 2. Trends of patient demographics and comorbidities from 2010 to 2017 for unique patients with multiple primary heart failure hospitalizations.