Key Points

Question

How has deceased organ donation by race and ethnicity changed over time in the US?

Findings

In this population-based cohort study, the greatest increases in donation ratios (actual deceased donors to potential donors) were seen in Black and American Indian/Alaska Native populations from 1999 to 2017. Although these increases attenuated racial differences, Black and American Indian/Alaska Native populations still donated at 69% and 28%, respectively, the rate of the White population, and ethnic differences increased over time, with Hispanic/Latino populations having a 4% lower donation ratio than non-Hispanic/Latino populations.

Meaning

Although deceased organ donation among some racial groups increased over time at a faster rate than among the White population, racial differences remain substantial.

This population-based cohort study examines changes by race/ethnicity in deceased organ donation over time in the US.

Abstract

Importance

Historically, deceased organ donation was lower among Black compared with White populations, motivating efforts to reduce racial disparities. The overarching effect of these efforts in Black and other racial/ethnic groups remains unclear.

Objective

To examine changes in deceased organ donation over time.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This population-based cohort study used data from January 1, 1999, through December 31, 2017, from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients to quantify the number of actual deceased organ donors, and from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research Detailed Mortality File to quantify the number of potential donors (individuals who died under conditions consistent with organ donation). Data were analyzed from December 2, 2019, to May 14, 2020.

Exposures

Race and ethnicity of deceased and potential donors.

Main Outcomes and Measures

For each racial/ethnic group and year, a donation ratio was calculated as the number of actual deceased donors divided by the number of potential donors. Direct age and sex standardization was used to allow for group comparisons, and Poisson regression was used to quantify changes in donation ratio over time.

Results

A total of 141 534 deceased donors and 5 268 200 potential donors were included in the analysis. Among Black individuals, the donation ratio increased 2.58-fold from 1999 to 2017 (yearly change in adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR], 1.05; 95% CI, 1.05-1.05; P < .001). This increase was significantly greater than the 1.60-fold increase seen in White individuals. Nevertheless, substantial racial differences remained, with Black individuals still donating at only 69% the rate of White individuals in 2017 (P < .001). Among other racial minority populations, changes were less drastic. Deceased organ donation increased 1.80-fold among American Indian/Alaska Native and 1.40-fold among Asian or Pacific Islander populations, with substantial racial differences remaining in 2017 (American Indian/Alaska Native population donation at 28% and Asian/Pacific Islander population donation at 85% the rate of the White population). Deceased organ donation differences between Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic/Latino populations increased over time (4% lower in 2017).

Conclusions and Relevance

The findings of this cohort study suggest that differences in deceased organ donation between White and some racial minority populations have attenuated over time. The greatest gains were observed among Black individuals, who have been the primary targets of study and intervention. Despite improvements, substantial differences remain, suggesting that novel approaches are needed to understand and address relatively lower rates of deceased organ donation among all racial minorities.

Introduction

Historically, in the US, deceased organ donation among all racial/ethnic minority populations was lower than that of White individuals.1,2,3,4 In the 1990s, the most common deceased organ donor was a White man aged 18 to 34 years,5 and less than 32% of deceased donor organs came from racial/ethnic minority populations.6

Relatively lower rates of deceased organ donation from minority populations not only affect the general supply of organs for transplant but have important implications on long-standing racial disparities among wait-listed candidates. For example, wait-listed candidates with blood type B, who are mostly racial/ethnic minority groups,7 have the longest wait times and receive fewer transplants than candidates with other blood types.8 Similar scenarios are seen in organs where human leukocyte antigen matching (which is correlated with race) is an allocation priority.9,10,11,12 Thus, increasing minority representation in the deceased donor pool is particularly relevant for minority individuals on the waiting list.

Over time, the transplant community has designed a number of interventions to address relatively lower rates of deceased organ donation among racial/ethnic minority populations.13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31 These interventions have incorporated culturally appropriate messaging,27 storytelling approaches,30 emphasis on personal connections and recognizable persons, and use of community workers, community-based organizations, and social networks with the intent of modifying knowledge, attitudes, and donor registration and consent behaviors. In-hospital interventions have adopted race- and sex-concordant teams to optimize family approach practice.32,33 However, the overarching effect of these efforts remains unclear.

Therefore, the goal of this study was to quantify how deceased organ donation among racial/ethnic groups has changed over time in the United States at the population level. We used publicly available, national mortality and transplant registry data to (1) define a reliable, comparable denominator of potential organ donors; (2) define a donation ratio as the number of actual donors divided by the number of potential donors; (3) quantify donation ratio changes within racial/ethnic groups over time; and (4) compare donation ratios between racial/ethnic groups.

Methods

Data Sources

This cohort study was a secondary analysis of deidentified data and was classified as exempt and not human subjects research by the institutional review board of Johns Hopkins University. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Data were collected from January 1, 1999, through December 31, 2017. We used data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Wide-ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR). The CDC WONDER online resource includes more than 20 collections of public-use data related to public health that are submitted by state and local health departments, the Public Health Service, and the academic public health community. The CDC Detailed Mortality File collection includes death counts and a single underlying cause of each death from death certificates at census region, state, and county levels. The CDC Detailed Mortality File also includes place of death (ie, inpatient medical facility, outpatient medical facility or emergency department, home, hospice, or long-term care facility) and month and weekday of death.

The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and transplant recipients in the US, submitted by the members of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). The Health Resources and Services Administration of the US Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors. Details of these data have been described elsewhere.34

Study Population

We used the CDC Detailed Mortality File (1999-2017) to study inpatient medical facility deaths that could have been organ donors. Given that the definition of a death eligible for donation varies across organ type and over time, we established a universal definition of eligible death as being 1 to 76 years of age and not having an underlying cause of death due to infection or malignant and in situ neoplasms. To identify potential donors, we used codes from the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), to exclude the following noneligible deaths according to OPTN criteria: bacterial, viral, fungal, parasitic, and prion infections (ICD-10 codes A00-B99). We also excluded deaths due to malignant and in situ neoplasms (ICD-10 codes C00-D09), polycythemia vera (ICD-10 code D45), myelodysplastic syndromes (ICD-10 code D46), neoplasms of uncertain or unknown behavior (ICD-10 codes D47-D48), aplastic and other anemias (ICD-10 codes D60-D64), agranulocytosis (ICD-10 code D70), functional disorders of the polymorphonuclear neutrophils (ICD-10 code D71), and other disorders of white blood cells (ICD-10 code D72). After applying OPTN exclusion criteria, the population remaining constituted potential organ donors. We then used SRTR data on organs recovered to ascertain the actual number of deceased organ donors. Organ types included kidney, heart, lung, and liver, and actual deceased organ donors were counted only once in the case of multiple recovered organs from 1 donor.

Classification of Race and Ethnicity

We defined race and ethnicity according to the Office of Management and Budget 1997 Standards for Maintaining, Collecting, and Presenting Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. Racial classifications included non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black or African American, Asian or Pacific Islander, and American Indian or Alaska Native; ethnic categories included Hispanic/Latino.

Donation Ratio

We defined the donation ratio as the absolute number of deceased donors (using SRTR data) divided by the number of eligible deaths (using CDC WONDER data). For each year and racial and ethnic group, we calculated the crude donation ratio. To account for differences in the age distribution of death between racial/ethnic groups, we also calculated adjusted (standardized) donation ratios using direct standardization for age of death (stratified in decades) and sex. To understand how donation changed over time, we used modified Poisson regression, adjusting for age, sex, and race. Analyses that were stratified by racial and ethnic groups were adjusted for age and sex only.

Sensitivity Analyses

To explore differences in eligible death definitions across organ types and over time, we applied additional, unique exclusion criteria to our universal definition of eligible death according to organ type. For kidney, we excluded inpatient deaths with underlying causes of death due to glomerular diseases (ICD-10 codes N00-N07), chronic kidney failure and end-stage kidney disease (ICD-10 code N18), and congenital malformations of the urinary tract system (ICD-10 codes Q60-Q64). For heart/lung, we excluded deaths among persons older than 60 years and deaths due to hypertensive disease (ICD-10 codes I10-I15), ischemic heart disease (ICD-10 codes I20-I25), myocarditis (ICD-10 code I40), cardiomyopathy (ICD-10 code I42), influenza and pneumonia (ICD-10 codes J09-J18), and chronic lower respiratory tract disease (ICD-10 codes J40-J47). For liver, we excluded deaths due to liver disease (ICD-10 codes K70-K76). For contemporary policies allowing for donation from donors with HIV and viral hepatitis, we limited the study period to 2014 to 2017 and excluded underlying causes of death due to bacterial, viral, fungal, parasitic, and prion infections (ICD-10 codes A00-B99), with the exception of HIV (ICD-10 codes B20-B24) and viral hepatitis (ICD-10 codes B15-B19).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed from December 2, 2019, to May 14, 2020. All analyses were performed using STATA/MP, version 16.0, for Linux (StataCorp, LLC), with 2-sided P < .05 considered statistically significant.

Results

Overall Temporal Trends

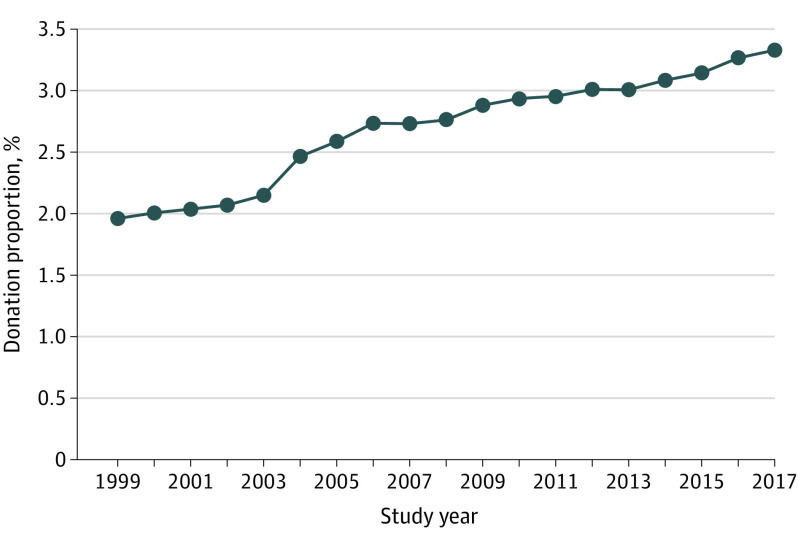

We identified 141 534 deceased donors and 5 268 200 potential donors (eTable 1 in the Supplement). The overall standardized donation ratio increased from 1.96% in 1999 to 3.30% in 2017 (Figure 1). This change translated into a 3% increase per year across the study period (adjusted incidence rate ratio [aIRR], 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.03; P < .001).

Figure 1. Overall Age- and Sex-Standardized Deceased Organ Donation Rate From 1999 to 2017.

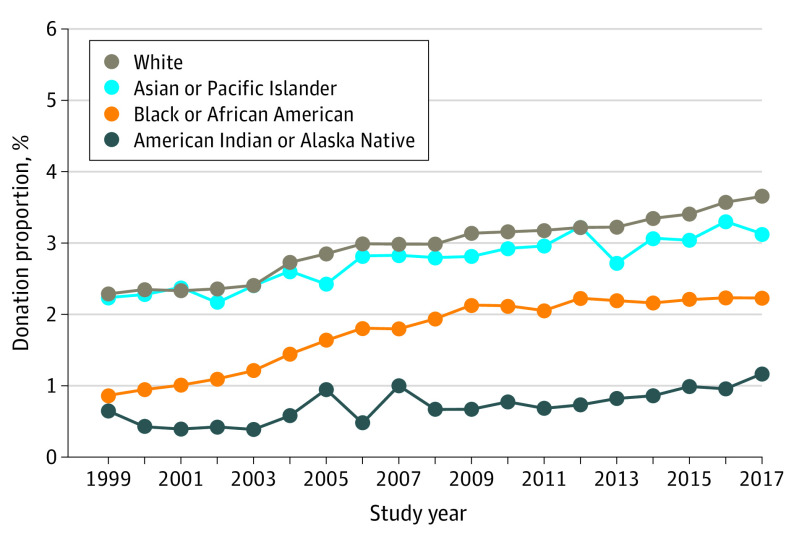

Temporal Trends by Race

The trends varied across racial groups. For White individuals, the standardized donation ratio increased from 2.29% in 1999 to 3.66% in 2017 (Figure 2), an overall 1.60-fold increase, or a 3% increase per year across the study period (aIRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.03; P < .001) (Table 1 and eTable 2 in the Supplement). For Black individuals, the standardized donation ratio increased from 0.87% to 2.23%, an overall 2.58-fold increase, or a 5% increase per year (aIRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.05-1.05; P < .001). This increase over time was significantly higher than the increase over time in White individuals (P < .001). For American Indian or Alaska Native groups, the standardized donation ratio increased from 0.65% to 1.17%, an overall 1.80-fold increase, which translated into a 3% increase per year (aIRR, 1.05; 95% CI, 1.03-1.06; P < .001). This increase over time was also significantly higher than the increase over time in White individuals (P = .007). For Asian or Pacific Islander groups, the standardized donation ratio increased from 2.24% to 3.13%, an overall 1.40-fold increase, or a 2% increase per year (aIRR, 1.02; 95% CI, 1.02-1.03; P < .001). This yearly change was similar to yearly changes for White individuals (P = .60).

Figure 2. Age- and Sex-Standardized Deceased Organ Donation Rate by Race From 1999 to 2017.

Table 1. Age- and Sex-Standardized aIRR of Donation in 1999 and 2017.

| Category | aIRR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2017 | Yearly increase | |

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (1.02-1.03) |

| Black | 0.46 (0.45-0.47) | 0.69 (0.67-0.70) | 1.05 (1.05-1.05) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.88 (0.82-0.94) | 0.85 (0.81-0.90) | 1.02 (1.02-1.03) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.20 (0.17-0.24) | 0.28 (0.25-0.32) | 1.05 (1.03-1.06) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (1.02-1.04) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.99 (0.96-1.02) | 0.96 (0.93-0.98) | 1.03 (1.02-1.03) |

Abbreviation: aIRR, adjusted incidence rate ratio.

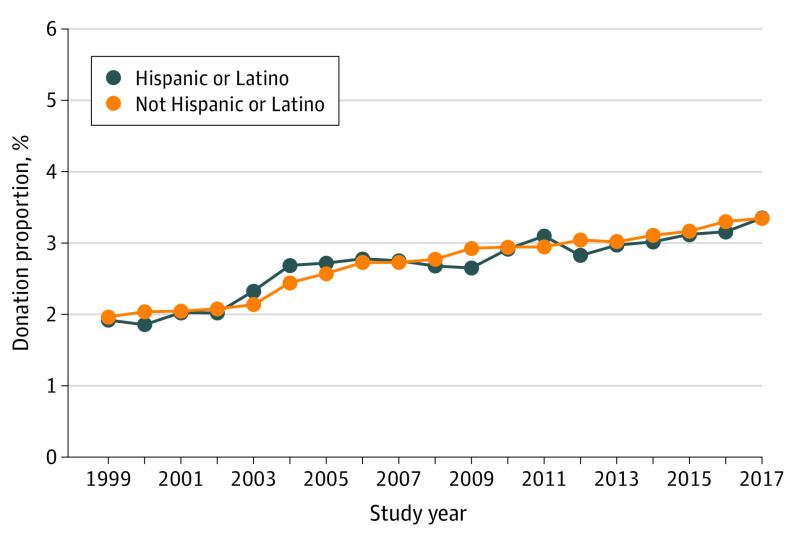

Temporal Trends by Ethnicity

The trends also varied by ethnicity. For non-Hispanic/Latino groups, the standardized donation ratio increased from 1.97% in 1999 to 3.35% in 2017 (Figure 3), an overall 1.70-fold increase, or a 3% increase per year across the study period (aIRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.04; P < .001) (Table 1 and eTable 3 in the Supplement). For Hispanic/Latino groups, the standardized donation ratio increased from 1.92% to 3.35%, a 1.74-fold increase, or a 3% increase per year (aIRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.03; P < .001). This increase over time was not significantly different than the increase seen in non-Hispanic/Latino individuals (P = .17).

Figure 3. Age- and Sex-Standardized Deceased Organ Donation Ratio by Ethnicity From 1999 to 2017.

Differences According to Race and Ethnicity

In 1999, Asian or Pacific Islander individuals donated at 88% the rate of White individuals; Black individuals, at 46% the rate of White individuals; and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals, at 20% the rate of White individuals (Table 1). Hispanic/Latino donation rates were not significantly different from non-Hispanic/Latino rates. In 2017, racial differences attenuated but remained substantial; Asian or Pacific Islander individuals donated at 85% the rate of White individuals; Black individuals, at 69% the rate of White individuals; and American Indian/Alaska Native individuals, at 28% the rate of White individuals (Table 1). Different from 1999, Hispanic/Latino donation rates were 4% lower than non-Hispanic/Latino donation rates in 2017.

Sensitivity Analysis

Trends over time and differences in the standardized donation rates between White and racial and ethnic minority populations were similar when using different eligible death definitions specific to kidney, liver, and heart/lung (Table 2). When including potential donors with underlying causes of death due to HIV or viral hepatitis, the yearly increase in the standardized donation ratio from 2014 to 2017 was greatest for White individuals (aIRR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.02-1.05; P < .001) (eTable 4 in the Supplement).

Table 2. Age- and Sex-Standardized aIRR of Donation in 1999 and 2017 Stratified by Organ Type.

| Race/ethnicity by organ type | aIRR (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1999 | 2017 | Yearly increase | |

| Kidney | |||

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (1.03-1.03) |

| Black | 0.43 (0.42-0.44) | 0.63 (0.62-0.65) | 1.05 (1.05-1.05) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.85 (0.79-0.92) | 0.86 (0.81-0.91) | 1.03 (1.02-1.03) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.20 (0.17-0.24) | 0.29 (0.25-0.32) | 1.05 (1.03-1.06) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (1.03-1.03) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) | 0.96 (0.94-0.99) | 1.03 (1.03-1.03) |

| Liver | |||

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1.02 (1.02-1.02) |

| Black | 0.44 (0.43-0.45) | 0.70 (0.69-0.72) | 1.05 (1.05-1.05) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.80 (0.75-0.87) | 0.84 (0.79-0.89) | 1.03 (1.02-1.03) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.21 (0.18-0.26) | 0.31 (0.27-0.35) | 1.05 (1.03-1.06) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (1.03-1.03) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.00 (0.97-1.04) | 1.00 (0.97-1.03) | 1.03 (1.03-1.03) |

| Heart/lung | |||

| Race | |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (1.03-1.03) |

| Black | 0.38 (0.36-0.40) | 0.68 (0.67-0.71) | 1.06 (1.06-1.07) |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 0.60 (0.54-0.67) | 0.79 (0.73-0.85) | 1.04 (1.03-1.05) |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 0.22 (0.17-0.28) | 0.27 (0.23-0.32) | 1.04 (1.02-1.06) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic/Latino | 1 [Reference] | 1 [Reference] | 1.03 (1.03-1.03) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0.95 (0.91-1.00) | 0.97 (0.93-1.00) | 1.03 (1.03-1.04) |

Abbreviation: aIRR, adjusted incidence rate ratio.

Discussion

Using national mortality and transplant registry data, we found that increases in organ donation over time were greater among Black (2.58-fold between 1999 and 2017) and American Indian/Alaska Native (1.80-fold) compared with White (1.60-fold) groups. Despite these changes, racial differences remained, with Black and American Indian/Alaska Native groups donating at 69% and 28%, respectively, the rate of their White counterparts. We found that ethnic differences increased over time, with Hispanic/Latino populations having a 4% lower deceased organ donation rate relative to non-Hispanic/Latino populations in 2017.

Our findings of relatively lower donation rates among minority populations are consistent with prior studies in solid organ transplant1,8,35,36,37,38,39,40 and mirror racial differences seen in blood,41 hematopoietic stem cell,42 and biospecimen donations.43 However, we have shown that these differences are attenuating, with much higher gains in organ donation among Black individuals than other racial groups.

We found that American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian or Pacific Islander populations also have lower deceased organ donation rates relative to White individuals, and less improvement in donation rates was appreciated over time in these racial subgroups. This is especially important because the mortality rates and consequent potential pool for deceased donor organs have increased among American Indian/Alaska Native groups over time.44 Although there is a preponderance of studies of Black participants, donation practices and donation-related beliefs of American Indian/Alaska Native and Asian or Pacific Islander groups are less often studied and infrequently reported at the population level. American Indian individuals are less likely than White individuals to be registered as organ donors45 and described mechanisms have been similar to those of Black individuals. In prior studies, relatively lower deceased organ donation among racial minority populations has been attributed to religious affiliation,26,45,46 desire for bodily integrity at death,47,48 medical mistrust,49 skepticism about clinician motivations and clinical management of dying patients, and fear of organ misuse and inequitable allocation of organs.47,50 The consistency of the association between race and deceased organ donation over time and the risk factor similarity across racial groups might be reflective of marginalized status rather than inherent beliefs particular to a social group.

Our results indicate that despite research and intervention attempts, minimization of racial differences at the population level have not been fully realized. The Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative, the largest-scale intervention designed to increase deceased organ donation in 2003, was mostly effective in increasing donor consent rates for non-Hispanic White individuals in reported locations.51,52 The intervention provided training on best practices drawn from organ procurement organizations and hospitals with donor conversation rates of greater than 75% and included clinical triggers that allowed for more timely identification of potential donors, early referral, increased family coordinator resources, integrated process measurement, and establishment of oversight committees.51,53,54 In contrast, smaller-scale, community-driven interventions have been effective in increasing organ donation among Black individuals,15,16,17,19,55 and our population-level approach is likely masking these smaller geographic unit-level successes. Our findings suggest that these successful efforts might need to be scaled up, funded, and widely disseminated to produce population-level change.

For most of our study period, we found that donation rates were similar between Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic/Latino groups, which is a novel finding that might be explained by our ethnicity definition and standardization methods. Our ethnicity category included potential donors of any race (ie, Hispanic/Latino individuals could be Black, White, Asian or Pacific Islander, or American Indian/Alaska Native), unlike many previous studies that grouped race and ethnicity together (ie, White, Black, Hispanic/Latino, etc, as separate categories). Our number of actual deceased donors and ethnic differences in 2017 are consistent with those of prior studies reporting higher donation rates in non-Hispanic/Latino relative to Hispanic/Latino groups.36,56 It might also be that accounting for the age and sex distribution of mortality between ethnic groups is highly informative. Other studies have found more granular components of ethnicity, such as acculturation, to be associated with organ donation.57 Acculturation, among other ethnicity-related factors,58 such as immigration status or country of origin,59,60,61 which we are unable to capture with our data sources, might prove to be informative in explaining heterogeneity in findings across published studies.

Our findings that substantial racial differences in organ donation remain, even after many concerted efforts, suggest that perhaps novel approaches are needed to address racial/ethnic differences in deceased organ donation. Historically, research has been focused on understanding presumed inherent minority attitudes and beliefs regarding donation,62,63 with resultant interventions that are mostly donor and donor family centric, intended to modify individual behavior.23,25,27,63,64 Compared with empirical research into individual-level factors, a robust contextual understanding is largely missing. Many researchers of health disparities and theoretical experts have advocated for a shift away from research solely focused on individual behaviors when seeking to address racial disparities in health,65,66 because racial disparities are most often explained by differential treatment, opportunity, and access to knowledge and resources to maintain and improve health.65,67,68,69,70 There is a small research base that has identified factors unrelated to potential donor and donor family knowledge, beliefs, and behavior. After accounting for race, contextual risk factors associated with geography, such as concentrated disadvantage, socioeconomic deprivation, and residential segregation, have been found to be associated with organ donation.71,72,73 Requestor communication skills and interpersonal interactions with families have been found to partly explain geographic differences in donor authorization,74 which vary widely across geographies in the US.75 Requestor behaviors also vary across race, with White families more often being approached for donation consent than Black families irrespective of setting and cause of death.76 Among Black families approached for donation, those who refuse more often report feeling pressured and having low-quality discussions with requestors, but have similar attitudes toward donation as families who authorize donation.77 Donor family management and communication quality, among other steps of the donor authorization and recovery process, remain unchecked, and when evaluated demonstrate reporting inaccuracies.78,79 Furthermore, current publicly reported data at the population level do not support this lens of empirical research.80

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of our study is that we have used publicly available national mortality data to create a denominator of potential donors that is comparable across racial/ethnic groups and through time. At present, the numbers of potential donors in defined geographic units across the US are obtained by self-report from organ procurement organizations, and organ procurement organization performance comparisons using potential deaths have been regarded as being unverifiable and inaccurate.78,79,81 As a result, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services is considering other data sources,82 such as national mortality data based on death certificates, to standardize potential donor pool ascertainment across organ procurement organizations.

Our work is not without limitations. The CDC Detailed Mortality File includes data based on death certificates, which have a single underlying cause of death for each US resident.83 Therefore, potential donors who met our eligible death definitions may have had contraindications to donation that were not documented in the underlying cause of death, resulting in an overestimation of potential donors. Similarly, we are unable to determine whether donors met brain or cardiac death criteria for donation, which, if known, would make our potential donor pool smaller. The overestimation of potential donors is unlikely to threaten our inference, given that our definitions were not differentially applied across racial/ethnic groups. We used Office of Management and Budget standards for race/ethnicity categorization, which have become less precise as the US has become increasingly diverse.84 A different racial/ethnic categorization scheme might produce different inference, and misclassification of racial assignment may also be masking more relevant distinguishing characteristics associated with donation. Further, while federal Office of Management and Budget standards guide us in data presentation at the practical level, race is socially assigned,85,86,87,88 and we are unable to capture the influence of the real-life social assignment on deceased organ donation. Although our national mortality data lack granularity such as ventilation or severe sepsis, concordance is high between donation rates calculated using these data compared with more granular state data (Pearson correlation coefficient, 0.97).89 Therefore, our inability to account for these nuances in national mortality data are unlikely to threaten our conclusions.

Conclusions

In this 18-year national study, we found that decreased organ donation among some racial groups increased over time at a faster rate than among White individuals, but differences between White and all racial minority groups remained. Our findings suggest that novel approaches are likely needed to understand and address relatively lower deceased organ donation among all racial minorities.

eTable 1. Crude Counts of Actual and Potential Donors per Year

eTable 2. Crude Counts of Actual and Potential Donors per Race per Year

eTable 3. Crude Counts of Actual and Potential Donors per Ethnicity per Year

eTable 4. Age and Sex-Standardized Incidence Rate Ratio of Donation in 2014 and 2017 for Potential Donors With Death Due to HIV or Viral Hepatitis

References

- 1.Nathan HM, Conrad SL, Held PJ, et al. Organ donation in the United States. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(s4)(suppl 4):29-40. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.3.s4.4.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pillay P, Van Thiel DH, Gavaler JS, Starzl TE. Effect of race upon organ donation and recipient survival in liver transplantation. Dig Dis Sci. 1990;35(11):1391-1396. doi: 10.1007/BF01536746 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez LM, Schulman B, Davis F, Olson L, Tellis VA, Matas AJ. Organ donation in three major American cities with large Latino and black populations. Transplantation. 1988;46(4):553-557. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198810000-00017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gralnek IM, Liu H, Shapiro MF, Martin P. The United States liver donor population in the 1990s: a descriptive, population-based comparative study. Transplantation. 1999;67(7):1019-1023. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199904150-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper AM, Rosendale JD. The UNOS OPTN waiting list and donor registry: 1988-1996. Clin Transpl. 1996;69-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine. Organ Donation: Opportunities for Action. National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Garratty G, Glynn SA, McEntire R; Retrovirus Epidemiology Donor Study . ABO and Rh(D) phenotype frequencies of different racial/ethnic groups in the United States. Transfusion. 2004;44(5):703-706. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2004.03338.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hart A, Smith JM, Skeans MA, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2018 annual data report: kidney. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(suppl s1):20-130. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hall EC, Massie AB, James NT, et al. Effect of eliminating priority points for HLA-B matching on racial disparities in kidney transplant rates. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(5):813-816. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.05.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bryan CF, Harrell KM, Mitchell SI, et al. HLA points assigned in cadaveric kidney allocation should be revisited: an analysis of HLA class II molecularly typed patients and donors. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(4):459-464. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-6143.2003.00093.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts JP, Wolfe RA, Bragg-Gresham JL, et al. Effect of changing the priority for HLA matching on the rates and outcomes of kidney transplantation in minority groups. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(6):545-551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa025056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaston RS, Ayres I, Dooley LG, Diethelm AG. Racial equity in renal transplantation: the disparate impact of HLA-based allocation. JAMA. 1993;270(11):1352-1356. doi: 10.1001/jama.1993.03510110092038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappel DF, Whitlock ME, Parks-Thomas TD, Hong BA, Freedman BK. Increasing African American organ donation: the St Louis experience. Transplant Proc. 1993;25(4):2489-2490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hong BA, Kappel DF, Whitlock M, Parks-Thomas T, Freedman B. Using race-specific community programs to increase organ donation among blacks. Am J Public Health. 1994;84(2):314-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Callender CO, Miles PV. Minority organ donation: the power of an educated community. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210(5):708-715. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.02.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Callender CO, Koizumi N, Miles PV, Melancon JK. Organ donation in the United States: the tale of the African-American journey of moving from the bottom to the top. Transplant Proc. 2016;48(7):2392-2395. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2016.02.094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callender CO, Hall MB, Branch D. An assessment of the effectiveness of the Mottep model for increasing donation rates and preventing the need for transplantation—adult findings: program years 1998 and 1999. Semin Nephrol. 2001;21(4):419-428. doi: 10.1053/snep.2001.23778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callender CO. Organ donation in blacks: a community approach. Transplant Proc. 1987;19(1, pt 2):1551-1554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Callender C, Burston B, Yeager C, Miles P. A national minority transplant program for increasing donation rates. Transplant Proc. 1997;29(1-2):1482-1483. doi: 10.1016/S0041-1345(96)00697-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Resnicow K, Andrews AM, Beach DK, et al. Randomized trial using hair stylists as lay health advisors to increase donation in African Americans. Ethn Dis. 2010;20(3):276-281. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salim A, Ley EJ, Berry C, et al. Effect of community educational interventions on rate of organ donation among Hispanic Americans. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(9):899-902. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salim A, Ley EJ, Berry C, et al. Increasing organ donation in Hispanic Americans: the role of media and other community outreach efforts. JAMA Surg. 2014;149(1):71-76. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2013.3967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salim A, Berry C, Ley EJ, Schulman D, Navarro S, Chan LS. Utilizing the media to help increase organ donation in the Hispanic American population. Clin Transplant. 2011;25(6):E622-E628. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0012.2011.01505.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salim A, Berry C, Ley EJ, et al. Increasing intent to donate in Hispanic American high school students: results of a prospective observational study. Transplant Proc. 2013;45(1):13-19. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.08.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andrews AM, Zhang N, Magee JC, Chapman R, Langford AT, Resnicow K. Increasing donor designation through black churches: results of a randomized trial. Prog Transplant. 2012;22(2):161-167. doi: 10.7182/pit2012281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Salim A, Bery C, Ley EJ, et al. A focused educational program after religious services to improve organ donation in Hispanic Americans. Clin Transplant. 2012;26(6):E634-E640. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arriola KR, Robinson DH, Perryman JP, Thompson NJ, Russell EF. Project ACTS II: organ donation education for African American adults. Ethn Dis. 2013;23(2):230-237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Loughery C, Zhang N, Resnicow K, Chapman R, Magee JC, Andrews AM. Peer leaders increase organ donor designation among members of historically African American fraternities and sororities. Prog Transplant. 2017;27(4):369-376. doi: 10.1177/1526924817732022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Redmond N, Harker L, Bamps Y, et al. Implementation of a web-based organ donation educational intervention: development and use of a refined process evaluation model. J Med internet Res. 2017;19(11):e396. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.DuBay D, Morinelli T, Redden D, et al. A video intervention to increase organ donor registration at the Department of Motorized Vehicles. Transplantation. 2020;104(4):788-794. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000002880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jacob Arriola KR, Redmond N, Williamson DHZ, et al. A community-based study of giving ACTS: organ donation education for African American adults. J Natl Med Assoc. 2019;111(2):185-192. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2018.09.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bodenheimer HC Jr, Okun JM, Tajik W, et al. The impact of race on organ donation authorization discussed in the context of liver transplantation. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2012;123:64-77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baughn D, Auerbach SM, Siminoff LA. Roles of sex and ethnicity in procurement coordinator–family communication during the organ donation discussion. Prog Transplant. 2010;20(3):247-255. doi: 10.1177/152692481002000308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Massie AB, Kucirka LM, Segev DL. Big data in organ transplantation: registries and administrative claims. Am J Transplant. 2014;14(8):1723-1730. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Regalia K, Zheng P, Sillau S, et al. Demographic factors affect willingness to register as an organ donor more than a personal relationship with a transplant candidate. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(7):1386-1391. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3053-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Israni AK, Zaun D, Hadley N, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2018 annual data report: deceased organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(suppl s1):509-541. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goldberg DS, Halpern SD, Reese PP. Deceased organ donation consent rates among racial and ethnic minorities and older potential donors. Crit Care Med. 2013;41(2):496-505. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318271198c [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ellison MD, Breen TJ, Glascock F, McGaw LJ, Daily OP. Organ donation in the United States: 1988 through 1991. Clin Transpl. 1992;119-128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bennett LE, Glascock RF, Breen TJ, Ellison MD, Daily OP. Organ donation in the United States: 1988 through 1992. Clin Transpl. 1993;85-93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Israni AK, Zaun D, Rosendale JD, Schaffhausen C, Snyder JJ, Kasiske BL. OPTN/SRTR 2017 annual data report: deceased organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(suppl 2):485-516. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yazer MH, Delaney M, Germain M, et al. ; Biomedical Excellence for Safer Transfusion (BEST) Collaborative . Trends in US minority red blood cell unit donations. Transfusion. 2017;57(5):1226-1234. doi: 10.1111/trf.14039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Switzer GE, Bruce JG, Myaskovsky L, et al. Race and ethnicity in decisions about unrelated hematopoietic stem cell donation. Blood. 2013;121(8):1469-1476. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-06-437343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guerrero S, López-Cortés A, Indacochea A, et al. Analysis of racial/ethnic representation in select basic and applied cancer research studies. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):13978. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-32264-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996-2016. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.16932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ginossar T, Benavidez J, Gillooly ZD, Kanwal Attreya A, Nguyen H, Bentley J. Ethnic/racial, religious, and demographic predictors of organ donor registration status among young adults in the southwestern United States. Prog Transplant. 2017;27(1):16-22. doi: 10.1177/1526924816665367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robinson DH, Perryman JP, Thompson NJ, Amaral S, Arriola KR. Testing the utility of a modified organ donation model among African American adults. J Behav Med. 2012;35(3):364-374. doi: 10.1007/s10865-011-9363-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salim A, Schulman D, Ley EJ, Berry C, Navarro S, Chan LS. Contributing factors for the willingness to donate organs in the Hispanic American population. Arch Surg. 2010;145(7):684-689. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McNamara P, Guadagnoli E, Evanisko MJ, et al. Correlates of support for organ donation among three ethnic groups. Clin Transplant. 1999;13(1, pt 1):45-50. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0012.1999.t01-2-130107.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Boulware LE, Ratner LE, Sosa JA, Cooper LA, LaVeist TA, Powe NR. Determinants of willingness to donate living related and cadaveric organs: identifying opportunities for intervention. Transplantation. 2002;73(10):1683-1691. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200205270-00029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hernandez MC, Haddad NN, Cullinane DC, et al. ; EAST SBO Workgroup . The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma severity grade is valid and generalizable in adhesive small bowel obstruction. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2018;84(2):372-378. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davis BD, Norton HJ, Jacobs DG; The Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative . The Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative: has it made a difference? Am J Surg. 2013;205(4):381-386. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2012.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salim A, Berry C, Ley EJ, et al. The impact of race on organ donation rates in Southern California. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;211(5):596-600. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.06.390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shafer TJ, Wagner D, Chessare J, et al. US Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative increases organ donation. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2008;31(3):190-210. doi: 10.1097/01.CNQ.0000325044.78904.9b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative. Accessed March 16, 2020. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/ImprovementStories/OrganDonationBreakthroughCollaborative.aspx

- 55.Callender CO, Hall LE, Yeager CL, Barber JB Jr, Dunston GM, Pinn-Wiggins VW. Organ donation and blacks: a critical frontier. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(6):442-444. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108083250631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore SA, Myers O, Comfort D, Lu SW, Tawil I, West SD. Effects of ethnicity on deceased organ donation in a minority-majority state. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(6):1386-1391. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siegel JT, Alvaro EM, Jones SP. Organ donor registration preferences among Hispanic populations: which modes of registration have the greatest promise? Health Educ Behav. 2005;32(2):242-252. doi: 10.1177/1090198104272251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin SS, Kelsey JL. Use of race and ethnicity in epidemiologic research: concepts, methodological issues, and suggestions for research. Epidemiol Rev. 2000;22(2):187-202. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a018032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ríos A, López-Navas AI, Sánchez Á, et al. Emigration from Puerto Rico to Florida: multivariate analysis of factors that condition attitudes of the Puerto Rican population toward organ donation for transplant. Transplant Proc. 2018;50(2):312-315. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.11.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ríos A, López-Navas AI, Sánchez Á, et al. Does the attitude toward organ donation change as a function of the country where people emigrate? study between Uruguayan emigrants to the United States and Spain. Transplant Proc. 2018;50(2):334-337. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2017.11.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ríos A, López-Navas AI, García JA, et al. The attitude of Latin American immigrants in Florida (USA) towards deceased organ donation: a cross section cohort study. Transpl Int. 2017;30(10):1020-1031. doi: 10.1111/tri.12997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Berry C, Salim A, Ley EJ, et al. Organ donation and Hispanic American high school students: attitudes, beliefs, perceptions, and intent to donate. Am Surg. 2012;78(2):161-165. doi: 10.1177/000313481207800232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Resnicow K, Andrews AM, Zhang N, et al. Development of a scale to measure African American attitudes toward organ donation. J Health Psychol. 2012;17(3):389-398. doi: 10.1177/1359105311412836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Locke JE, Qu H, Shewchuk R, et al. Identification of strategies to facilitate organ donation among African Americans using the nominal group technique. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(2):286-293. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05770614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936-944. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Krieger N. Theories for social epidemiology in the 21st century: an ecosocial perspective. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(4):668-677. doi: 10.1093/ije/30.4.668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Krieger N. Discrimination and health inequities. Int J Health Serv. 2014;44(4):643-710. doi: 10.2190/HS.44.4.b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Rehkopf DH, Subramanian SV. Race/ethnicity, gender, and monitoring socioeconomic gradients in health: a comparison of area-based socioeconomic measures—the Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1655-1671. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.93.10.1655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. J Health Soc Behav. 1995;(spec no):80-94. doi: 10.2307/2626958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Link BG, Phelan JC. McKeown and the idea that social conditions are fundamental causes of disease. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(5):730-732. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.92.5.730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shacham E, Loux T, Barnidge EK, Lew D, Pappaterra L. Determinants of organ donation registration. Am J Transplant. 2018;18(11):2798-2803. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ladin K, Wang R, Fleishman A, Boger M, Rodrigue JR. Does social capital explain community-level differences in organ donor designation? Milbank Q. 2015;93(3):609-641. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wadhwani SI, Brokamp C, Rasnick E, Bucuvalas JC, Lai JC, Beck AF. Neighborhood socioeconomic deprivation, racial segregation, and organ donation across 5 states. Am J Transplant. 2020. doi: 10.1111/ajt.16186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Traino HM, Molisani AJ, Siminoff LA. Regional differences in communication process and outcomes of requests for solid organ donation. Am J Transplant. 2017;17(6):1620-1627. doi: 10.1111/ajt.14165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Goldberg DS, French B, Abt PL, Gilroy RK. Increasing the number of organ transplants in the United States by optimizing donor authorization rates. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(8):2117-2125. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Guadagnoli E, McNamara P, Evanisko MJ, Beasley C, Callender CO, Poretsky A. The influence of race on approaching families for organ donation and their decision to donate. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(2):244-247. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.89.2.244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Siminoff LA, Alolod GP, Gardiner HM, Hasz RD, Mulvania PA, Wilson-Genderson M. A comparison of the content and quality of organ donation discussions with African American families who authorize and refuse donation. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020. doi: 10.1007/s40615-020-00806-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Siminoff LA, Nelson KA. The accuracy of hospital reports of organ donation eligibility, requests, and consent: a cross-validation study. Jt Comm J Qual Improv. 1999;25(3):129-136. doi: 10.1016/S1070-3241(16)30432-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Siminoff LA, Gardiner HM, Wilson-Genderson M, Shafer TJ. How inaccurate metrics hide the true potential for organ donation in the United States. Prog Transplant. 2018;28(1):12-18. doi: 10.1177/1526924818757939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Doby BL, Boyarsky BJ, Gentry S, Segev DL. Improving OPO performance through national data availability. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(10):2675-2677. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cannon RM, Jones CM, Davis EG, Franklin GA, Gupta M, Shah MB. Patterns of geographic variability in mortality and eligible deaths between organ procurement organizations. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(10):2756-2763. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare and Medicaid programs: organ procurement organizations conditions for coverage: revisions to the outcome measure requirements for Organ Procurement Organization. Fed Regist. 2019;84(246):70628. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Use of vital and health records in epidemiologic research: a report of the United States National Committee on Vital and Health Statistics. Vital Health Stat 1. 1968;4(7):1-13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.US Census Bureau. 2015 National content test race and ethnicity analysis report. US Census Bureau. Published February 28, 2017. Accessed December 14, 2019. https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial/2020/program-management/final-analysis-reports/2015nct-race-ethnicity-analysis.pdf

- 85.Cooper RS. Race in biological and biomedical research. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2013;3(11):a008573. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a008573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jones CP. Invited commentary: “race,” racism, and the practice of epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(4):299-304. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.4.299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cooper RS, Nadkarni GN, Ogedegbe G. Race, ancestry, and reporting in medical journals. JAMA. 2018;320(15):1531-1532. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.LaVeist TA. Beyond dummy variables and sample selection: what health services researchers ought to know about race as a variable. Health Serv Res. 1994;29(1):1-16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goldberg DS, Doby B, Lynch R. Addressing critiques of the proposed CMS metric of organ procurement organ performance: more data isn’t better. Transplantation. 2019. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000003071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Crude Counts of Actual and Potential Donors per Year

eTable 2. Crude Counts of Actual and Potential Donors per Race per Year

eTable 3. Crude Counts of Actual and Potential Donors per Ethnicity per Year

eTable 4. Age and Sex-Standardized Incidence Rate Ratio of Donation in 2014 and 2017 for Potential Donors With Death Due to HIV or Viral Hepatitis