Abstract

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori)—a human gastric pathogen—forms a major risk factor for the development of various gastric pathologies such as chronic inflammatory gastritis, peptic ulcer, lymphomas of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissues, and gastric carcinoma. The complete eradication of infection is the primary objective of treating any H. pylori-associated gastric condition. However, declining eradication efficiencies, off-target effects, and patient noncompliance to prolong and broad-spectrum antibiotic treatments has spurred the clinical interest to search for alternative effective and safer therapeutic options. As natural compounds are safe and privileged with high levels of antibacterial-activity, previous studies have tested and reported a plethora of such compounds with potential in vitro/in vivo anti-H. pylori activity. However, the mode of action of majority of these natural compounds is unclear. The present study has been envisaged to compile the information of various such natural compounds and to evaluate their binding with histone-like DNA-binding proteins of H. pylori (referred here as Hup) using in silico molecular docking-based virtual screening experiments. Hup—being a major nucleoid-associated protein expressed by H. pylori—plays a strategic role in its survival and persistent colonization under hostile stress conditions. The ligand with highest binding energy with Hup—that is, epigallocatechin-(−)gallate (EGCG)—was rationally selected for further computational and experimental testing. The best docking poses of EGCG with Hup were first evaluated for their solution stability using long run molecular dynamics simulations and then using fluorescence and nuclear magnetic resonance titration experiments which demonstrated that the binding of EGCG with Hup is fairly strong (the resultant apparent dissociation constant (kD) values were equal to 2.61 and 3.29 ± 0.42 μM, respectively).

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori, curved Gram-negative bacillus bacteria) is the most common human gastric pathogen as it colonizes the gastric mucosa of about half of the world’s population and the infection level may reach over 70% in developing countries like India.1 Compared to other pathogenic bacteria, H. pylori has its remarkable ability to survive and colonize persistently under inhospitable acidic conditions of the human stomach and can survive there for lifelong if no antibiotic treatment is given.2−4 The H. pylori infection in gastric mucosa has been associated with various gastrointestinal diseases, including inflammatory gastritis, peptic ulceration, noncardia gastric adenocarcinoma, gastric mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric cancer.5−8 In the year 1994, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), a subordinate organization of the World Health Organization (WHO), designated H. pylori infection as a class-I carcinogen.9 Studies have shown that eradication of H. pylori greatly reduces the recurrence rate of gastric cancer and other H. pylori-associated gastric pathologies.10−12 The currently used standard eradication therapies involve two broad-spectrum antibiotics in combination with a proton pump inhibitor and further supplemented with a bismuth compound (e.g. ranitidine bismuth citrate).13,14 Bismuth-based quadruple therapy is often continued for about two weeks (i.e. for 10–14 days) to achieve complete eradication.15 However, the prolonged use of this combination therapy often shows undesirable side effects (particularly in aged population)12,16 and high rates of patient noncompliance resulting in treatment failure, reinfection, and emergence of antimicrobial resistance.12,17−19 Particularly, the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains has significantly decreased the H. pylori eradication rates (70–90%)20,21 and drives the need for an alternative safe and effective therapeutic strategy. With this consideration, a plethora of natural compounds have been tested and reported for their potential in vitro/in vivo anti-H. pylori (AHP) activity.20,22−35 Natural products derived from plant parts are often safe (i.e. have low side effects) and extremely rich in chemical diversity, compared to synthetic drugs obtained from industrial sources, and, on top of this, are privileged with useful pharmacological activities including antibacterial, anticancer, and antioxidative and anti-inflammatory effects. Therefore, natural products are gaining considerable interest among clinical researchers and gastroenterologists to develop time-effective therapeutic options for eradicating H. pylori infection with negligible adverse effects.16 However, the mode of action of majority of these natural compounds is unclear hampering their rational clinical use as well as their further modifications to achieve desired efficacy.

Continuing our efforts in this direction, the present study aims to search for natural compounds reported in the literature for in vitro/in vivo AHP activity. Next, using in silico molecular docking methods, the resultant natural product library is then virtually screened for those compounds binding efficiently with histone-like DNA-binding proteins of H. pylori. The protein—referred here as Hup—is currently under investigation in our laboratory owing to its potential relevance for developing therapeutic strategies against H. pylori. Hup has remarkable ability to maneuver the DNA topology and regulate multiple genes, including those involved in stress response and virulence.4,36,37 Additionally, Hup plays an important role in nucleoid compaction and protects H. pylori DNA from acidic and oxidative damage as well.38,39 Therefore, it is legitimate to believe that targeting the functioning of Hup through small molecules will definitely impact the survival and persistent colonization of H. pylori under harsh gastric conditions.

Results and Discussion

Comprehensive Compiling and Cataloguing of Natural Compounds Exhibiting AHP Activity

Natural products derived from plant parts (leaves, bark, roots, etc.) have been attractive starting points in the search for antimicrobial drugs as majority of these compounds have privileged antimicrobial activity and are extremely rich in chemical diversity and, on top of this, they have low side effects compared to synthetic drugs obtained from industrial sources.16,40,41 In recent decades, several natural products have shown promising AHP activity against drug-resistant and drug-susceptible strains of H. pylori, and several of these compounds are ready for next level preclinical studies and subsequent clinical trial testing.40,41 However, the mode of action of majority of these natural compounds is unclear. Here, we have attempted to compile various such natural compounds exhibiting AHP activity and further to identify those showing exquisite binding to H. pylori Hup. Table 1 contains the list of natural compounds reported in the literature for their promising AHP activity. In this preliminary study, we decided to identify only small sized natural compounds with molecular weight (MW) < 500 Da which can alter the functioning of H. pylori Hup. Accordingly, the compounds in Table 1 have been arranged into two types: low MW (LMW) compounds with MW < 500 Da (compounds 1–133) and high MW (HMW) compounds with MW > 500 Da (compounds 134–159). Before using the compound libraries for virtual screening, the natural compound structures were optimized for their molecular geometry and then subjected to energy minimization employing the OPLS3 force field.42 The ionization/tautomeric states of various compounds were generated with EPIK based on more accurate Hammett and Taft methodologies43 (see Supporting Information, Figure S1).

Table 1. Compiled List of Reported Natural Compounds Exhibiting AHP Activity.

| # (Compound ID) | PubChem ID | compound name | IC50 value (μg/mL) | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (1) | 2353 | berberine | 8–40 μg/mL | (22) |

| 2 (2–3) | 72300 | magnolol | 10–20 μg/mL | |

| 3 (4) | 442126 | decursin | 6–20 μg/mL | |

| 4 (5) | 0370 | gallic acid | 200 μg/mL | |

| 5 (6) | 444539 | cinnamic acid | 80–100 μg/mL | |

| 6 (7–8) | 25201019 | ponciretin | 10–20 μg/mL | (23) |

| 7 (9–10) | 5281789 | licoisoflavone | 6.25 μg/mL | |

| 8 (11–12) | 5281781 | irisolidone | 12.5–25 μg/mL | |

| 9 (13–14) | 5280961 | genistein | 890 μg/mL | |

| 10 (15) | 628528 | cabreuvin | 62.5 μg/mL | |

| 11 (16) | 72281 | hesperetin | 20–80 μg/mL | |

| 12 (17) | 637542 | caumeric acid | 10–160 μg/mL | (24) |

| 13 (18) | 689043 | caffeic acid | 0.5 μg/mL | |

| 14 (19) | 5281792 | rosmarinic acid | NR/A | |

| 15 (20) | 11644379 | (Z)-campherene-2β,13-diol | NR/A | (25) |

| 16 (21–22) | 11218565 | (Z)-7-hydroxy nuciferol | NR/A | |

| 17 (23) | 6857681 | Z(β)-santanol | 7.8–15.6 μg/mL | |

| 18 (24) | 15560069 | (Z)-lanceol | 7.8–31.3 μg/mL | |

| 19 (25) | 10114 | GrA | 0.4 μg/mL | (26) |

| 20 (26–27) | 1183 | venillin | >100 μg/mL | (27) |

| 21 (28) | 14287147 | 15-acetoxyisocuperrsic acid | 250 μg/mL | |

| 22 (29) | 14680349 | agathic acid-15-methylester | 130 μg/mL | |

| 23 (30) | 101297697 | agathalic acid | >100 μg/mL | |

| 24 (31–32) | 44584263 | viscidone | 100 μg/mL | |

| 25 (33–34) | 5352001 | ermanin | >100 μg/mL | |

| 26 (35–36) | 5459196 | betuletol | >100 μg/mL | |

| 27 (37–38) | 5281666 | kaempferide | >100 μg/mL | |

| 28 (39) | 7444 | azoene | NR/A | |

| 29 (40) | 167551 | anacardic acid | 10 μg/mL | (28) |

| 30 (41) | 443023 | syringaresinol | 500 μg/mL | (29) |

| 31 (42–43) | 3806 | juglone | 30 ± 4 μmol/L | (30) |

| 32 (44–45) | 92503 | vestitol | 12.5 μg/mL | (31) |

| 33 (46–47) | 5319013 | licoricone | 12.5–25 μg/mL | |

| 34 (48) | 480873 | 1-methoxyphaseollidin | 16 μg/mL | |

| 35 (49) | 480865 | licoricidin | 6.25–12.5 μg/mL | |

| 36 (50) | 114829 | liquiritigenin | 50 μg/mL | |

| 37 (51) | 124052 | glabridin | 12.5–25 μg/mL | |

| 38 (52) | 480774 | glabrene | 12.5 μg/mL | |

| 39 (53–54) | 5320083 | glycyrol | >50 μg/mL | |

| 40 (55) | 1794427 | chlorogenic acid | 6.25 μg/mL | (32) |

| 41 (56) | 440735 | eriodictyol | 50 μg/mL | |

| 42 (57–58) | 439533 | taxifolin | 25 μg/mL | |

| 43 (59–60) | 5281691 | rhamnetin | 50 μg/mL | |

| 44 (61–92) | 6442633 | spiciformin | 6.25–50 μg/mL | |

| 45 (93) | 7605278 | tanachin | NR/A | |

| 46 (94) | 445154 | resveratrol | 6.25–400 μg/mL | (33) |

| 47 (95–97) | 65064 | EGCG | 100 μg/mL | (34) |

| 48 (98) | 5281794 | shogaol | NR/A | |

| 49 (99–101) | 5281855 | ellagic acid | 6.25–50 μg/mL | (35) |

| 50 (102–103) | 5281672 | myricetin | >50 μg/mL | |

| 51 (104–108) | 969516 | curcumin | 5–50 μg/mL | (20) |

| 52 (109) | 358901 | phyllanthin | 97.7 μg/mL | |

| 53 (110) | 243 | benzoic acid | 60–320 mg/mL | |

| 54 (111) | 289 | catechol | 0.5 μg/mL | |

| 55 (112–113) | 5350 | isothiocyanate sulforaphane | 70 g/day | |

| 56 (114) | 6251 | mannitol | 0.5 μg/mL | |

| 57 (115) | 6344 | dichloromethane | 15.6 μg/mL | |

| 58 (116) | 6989 | thymol | 0.035 ± 0.13 mL/mL | |

| 59 (117–119) | 7428 | methylgallate | 97.7 μg/mL | |

| 60 (120) | 7461 | γ-terpinene | 0.035 ± 0.13 mL/mL | |

| 61 (121) | 7463 | p-cymene | 0.035 ± 0.13 mL/mL | |

| 62 (122) | 10364 | carvacrol | 0.035 ± 0.13 mL/mL | |

| 63 (123) | 10742 | syringic acid | 38 ± 2.2 μg/mL | |

| 64 (124–125) | 11092 | paeonol | 60–320 mg/mL | |

| 65 (126–127) | 17100 | α-terpineol | NR/A | |

| 66 (128) | 61041 | safranal | 32 μg/mL | |

| 67 (129–130) | 65036 | allicin | 32 μg/mL | |

| 68 (131–132) | 69600 | 2-hydroxy-4-methoxy benzaldehyde | 39 μg/mL | |

| 69 (133) | 10333023 | altissin | 6.25–50 μg/mL | |

| 70 (134) | 73174 | dehydrocostus lactone | 490 μg/mL | |

| 71 (135–136) | 73440 | dehydroleucodine | 1–8 mg/L | |

| 72 (137) | 83043 | 2,5-Bis(methoxycarbonyl)terephthalic acid | 12.5–400 μg/mL | |

| 73 (138–139) | 162350 | isovitexin | 6.25 μg/mL | |

| 74 (140) | 168114 | 8-gingerol | 10–160 μg/mL | |

| 75 (141) | 168115 | 10-gingerol | 10–160 μg/mL | |

| 76 (142–143) | 265237 | WA | NR/A | |

| 77 (144–145) | 287064 | protocatechuic | 10–160 μg/mL | |

| 78 (146) | 336327 | medicarpin | 25 μm | |

| 79 (147) | 439514 | scopolin | 50 μg/mL | |

| 80 (148) | 10333024 | sivasinolide | 6.25–50 μg/mL | |

| 81 (149) | 442793 | 6-gingerol | 10–160 μg/mL | |

| 82 (150) | 101401747 | psoracorylifol B | 12.5–25 μg/mL | |

| 83 (151) | 445858 | ferulic acid | 0.5 μg/mL | |

| 84 (152) | 637776 | methyl isoeugenol | NR/A | |

| 85 (153) | 638024 | piperine | NR/A | |

| 86 (154–155) | 5280441 | vitexin | 6.25 μg/mL | |

| 87 (156–157) | 42607682 | 3′-PR | 3.12–6.25 μg/mL | |

| 88 (158–159) | 5280443 | apigenin | 3.15 mg/mL | |

| 89 (160–161) | 5280445 | luteolin | 5–10 μg/mL | |

| 90 (162–163) | 5280459 | quercetin-3-rhamnoside | 97.7 μg/mL | |

| 91 (164–165) | 5280460 | scopoletin | 50 μg/mL | |

| 92 (166–167) | 5281605 | baicalein | 5–10 μg/mL | |

| 93 (168–170) | 5281650 | α-mangostin | 31.3 μg/mL | |

| 94 (171–172) | 5281811 | tectorigenin | 100 μm | |

| 95 (173–174) | 5281832 | arborinine | ≤200 μg/mL | |

| 96 (175–176) | 5318998 | licochalcone A | NR/A | |

| 97 (177–184) | 5319518 | methyl brevifolincarboxylate | 97.7 μg/mL | |

| 98 (185–186) | 5320946 | rhamnocitrin | 97.7 μg/mL | |

| 99 (187) | 5470187 | zerumbone | 250 μg/mL | |

| 100 (188–189) | 5495925 | β-mangostin | 250 μg/mL | |

| 101 (190–192) | 6419835 | CG | NR/A | |

| 102 (193) | 6451060 | ovatodiolide | 50–100 μm | |

| 103 (194–195) | 9548634 | glucoraphanin | NR/A | |

| 104 (196) | 10095770 | wistin | 100 μm | |

| 105 (197–199) | 10386850 | cowaxanthone | 4.6 μm | |

| 106 (200) | 10955174 | patchouli alcohol | 20 μm | |

| 107 (201) | 11165077 | 6S,9R roseoside | 6.25 μg/mL | |

| 108 (202) | 11223782 | phyltetralin | 97.7 μg/mL | |

| 109 (203) | 11673265 | lippidulcine | NR/A | |

| 110 (204–206) | 11827150 | fuscaxanthone I | 4.6 μm | |

| 111 (207) | 16091559 | peroxylippidulcine | NR/A | |

| 112 (208–211) | 44258361 | isoembigenin | 6.25 μg/mL | |

| 113 (212–215) | 44421210 | isomasticadienolic acid | 0.202 mg/mL | |

| 114 (216–217) | 52947057 | methylantcinate | 50 mm | |

| 115 (218–219) | 62379750 | 1-(5-chloro-2-hydroxyphenyl)-3-methylbutan-1-one | 12.5–400 μg/mL | |

| 116 (220) | 92023653 | fucoidan | NR/A | |

| 117 (221) | 101918993 | neolignan ketone | 6.25 μg/mL | |

| 118 (222–224) | 4970 | protopine | 100 μg/mL | |

| 119 (25–228) | 11620 | l-sulforaphene | 4–32 μg/mL | |

| 120 (229) | 16871 | 2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone | 0.156–0.625 μg/mL | |

| 121 (230) | 10682896 | boropinic acid | 1.62 μg/mL | |

| 122 (231) | 78160 | erucin | 4–32 μg/mL | |

| 123 (232) | 179806 | 5,7-dihydroxy-8-methyl-6-prenylflavanone | NR/A | |

| 124 (233–235) | 197835 | β-hydrastine | 100.0 μg/mL | |

| 125 (236–237) | 206035 | alyssin | 4–32 μg/mL | |

| 126 (238) | 206037 | berteroin | 4–32 μg/mL | |

| 127 (239) | 442361 | 7,4′-dihydroxy-8-methylflavan | 31.3 μM | |

| 128 (240) | 3080557 | erysolin | 4–32 μg/mL | |

| 129 (241) | 5281331 | spinasterol | 20–80 μg/mL | |

| 130 (242) | 5317303 | 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-8-tridecenyl]-4-(1H)-quinolone | >0.05 μg/mL | |

| 131 (243) | 5319779 | 1-methyl-2-[(Z)-7-tridecenyl]-4-(1H)-quinolone | 0.05 μg/mL | |

| 132 (244) | 14466152 | tatridin-A | 6.25–50 μg/mL | |

| 133 (245–246) | 11848147 | psoracorylifol A | 12.5–25 μg/mL | |

| 134 (1) | 9852086 | ginsenoside | NR/A | (20) |

| 135 (2–3) | 73178 | 1,2,3,6-tetra-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose | 8 μg/mL | |

| 136 (4–5) | 73568 | corilagin | 4 μg/mL | |

| 137 (6) | 114627 | neoeriocitrin | 0.625–5 (% v/v) | |

| 138 (7) | 442428 | naringin | 0.625–5 (% v/v) | |

| 139 (8) | 442439 | neohesperidin | 0.625–5 (% v/v) | |

| 140 (9–10) | 5280805 | rutin | 97.7 μg/mL | |

| 141 (11) | 5281800 | acteoside | 15–60 μg/mL | |

| 142 (12–13) | 5281847 | rottlerin | 312–625 μg/L | |

| 143 (14) | 5282153 | luteolin-7-O-β-d-diglucuronide | 90 μg/mL | |

| 144 (15–16) | 5388496 | punicalin | 125.0 μg/mL | |

| 145 (17) | 6439941 | terniflorin | 50–100 μm | |

| 146 (18) | 6476333 | isoacteoside | 50–100 μm | |

| 147 (19–20) | 10033935 | ellagitannin | 0.8 mg/mL | |

| 148 (21–22) | 16129778 | tannin | 125 μg/mL | |

| 149 (23–24) | 24847856 | arabinogalactan | NR/A | |

| 150 (25–26) | 44584733 | punicalagin | 0.8 mg/mL | |

| 151 (27–28) | 71436711 | brasiliensic acid | 50 μg/mL | |

| 152 (29–30) | 101304443 | isobrasiliensic acid | 12.5 μg/mL | |

| 153 (31–32) | 101973939 | fukugiside | 10.8 μm | |

| 154 (33–34) | 162221834 | gallagic acid | 125.0 μg/mL | |

| 155 (35) | 448438 | violaxanthin | >100 μg/mL | |

| 156 (36) | 5281247 | neoxanthin | 11–27 μg/mL | |

| 157 (37–38) | 12112747 | luteoxanthin | 7.9 μg/mL | |

| 158 (39–40) | 23634523 | cochinchinenin B | 29.5 μM | |

| 159 (41–42) | 23634528 | cochinchinenin C | 29.5 μM |

Construction of Dimeric and Monomeric Structures of H. pylori Hup by Homology Modeling

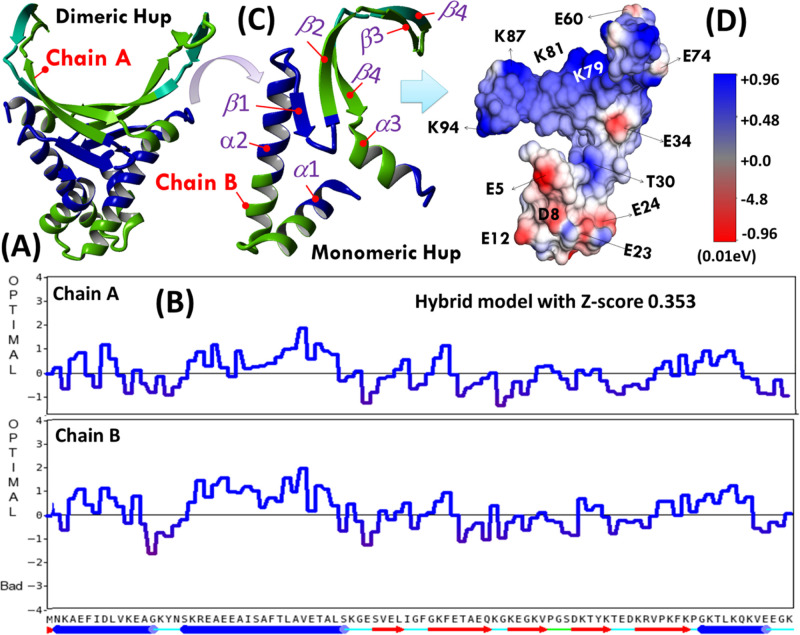

So far, there is no experimental three-dimensional (3D) structure available for H. pylori Hup; therefore, its structural model was generated using YASARA inbuilt homology modeling application. For structure modeling, we used a protein primary sequence of H. pylori Hup (in FASTA format), derived from H. pylori strain 26695 (equivalent ATCC strain 700392: https://www.uniprot.org/taxonomy/85962). Various models were first generated, and of them, five best models were then sorted out by their overall quality Z-scores: one monomeric model based on template PDB ID, 1HUU-B, and four dimeric models based on template PDB IDs: 5LVT, 5FBM, 4QJU, and 1P71 (the crystal structure of Anabaena HU). Finally, YASARA sought to combine the best parts of the models to obtain a hybrid model with Z-score 0.353 as shown in Figure 1A. The model quality parameter plotted as a function of residue number is shown in Figure 1B. It is clearly evident that the per-residue quality parameters for the dimerization domain (DD) were relatively better in chain B of dimeric Hup (HupD) compared to chain A. Therefore, it was decided to use chain B of the dimeric model as a model for the monomeric Hup (HupM) structure (extracted separately and shown in Figure 1C) for further computational studies. Structurally, the two subunits of Hup are intertwined to form a compact α-helical hydrophobic core with two positively charged β-ribbon arms as evident from the surface charge topology of HupM shown in Figure 1D. The positively charged β-arms form a binding pocket for interaction with negatively charged DNA structures. As shown in Figure 1C, the HupM structure is characterized by two subdomains: (a) the N-terminal DD ranging from residues M1–E41 and (b) the C-terminal DNA-binding domain (DBD) ranging from residues S42–K94. The DD domain is formed by two α-helices α1 (K3–K15) and α2 (K19-G40), whereas the DBD domain is formed by five β strands: β1(V43–I46), β2(G49-K57), β3(K59–V63), β4(T69-E73), and β5(K75-G83) and one α-helix (α3: K84–K94). Before using the YASARA-generated models for virtual screening, these were subjected to structural refinement employing the YASARA Energy Minimization Server (see the Supporting Information, Figures S2 and S3). In order to get more insights into the structural and dynamics features of the Hup protein under biological solution conditions, we further conducted molecular dynamics (MD) simulation employing YASARA Dynamics software.

Figure 1.

(A) YASARA generated homology model of homodimeric Hup of H. pylori and (B) corresponding residue number model quality scores plotted for two chains of HupD. (C) Ribbon diagram of the HupM structure extracted from chain-B of HupD model and (D) surface charged topology of the HupM structure.

Virtual Screening of Dimeric and Monomeric Structures of H. pylori Hup

Virtual screening of YASARA generated Hup structures against in-house created LMW and HMW library of natural compounds was performed using both YASARA as well as Schrödinger, LLC softwares. YASARA allows screening of compounds based on two molecular docking approaches: AUTODOCK and VINA; whereas in Schrödinger, we used GLIDE module in an Extra Precision (XP) mode.

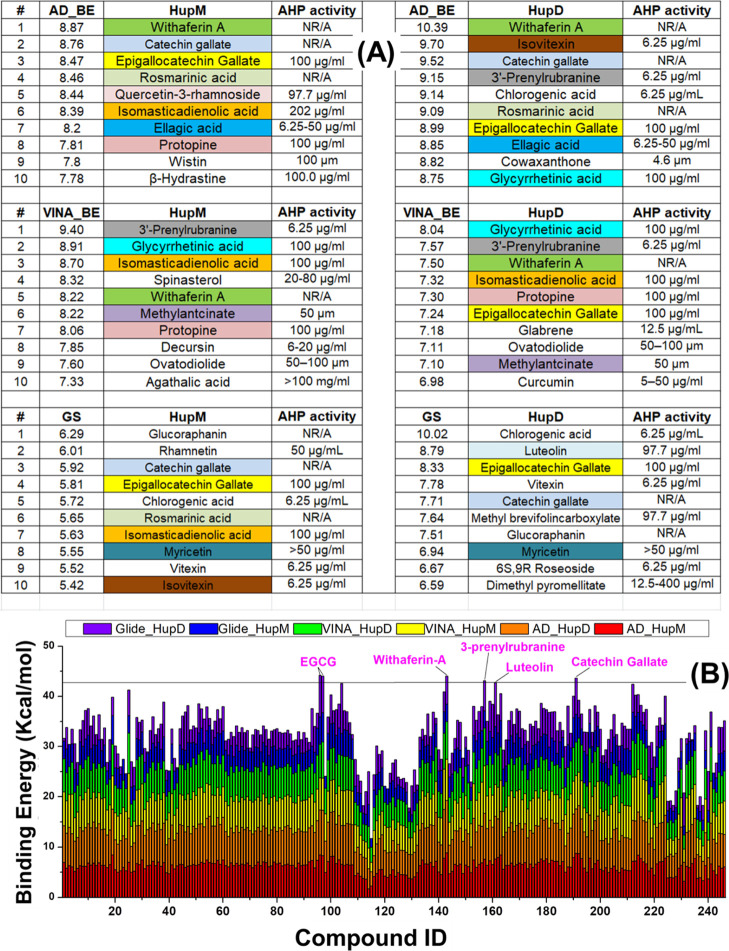

Recently, we characterized the structural and dynamics features of H. pylori Hup using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)-based methods and revealed that there exists a dynamic equilibrium between the monomeric and dimeric states of Hup and it is the dimeric state which binds with DNA.37 Further, the temperature-dependent studies revealed that at high temperature, the monomeric state of Hup dominates.37 The occurrence of the dynamic equilibrium legitimately offered the possibility of targeting Hup dimerization through small-molecule inhibitors binding to the dimerization interface.37 As HupM has limited interaction with DNA, targeting Hup-dimerization will serve the same purpose, that is, impaired Hup–DNA binding interaction. In other words, molecules suppressing Hup-dimerization or limiting Hup–DNA binding interaction will lead to same consequences: (a) disturbed DNA compaction to nucleoid under harsh acidic conditions, therefore, DNA will become liable for acidic denaturation, and (B) disturbed genome morphology and other DNA-dependent cellular activities like replication, recombination, repair, and transcription. With this background information, it is legitimate to consider virtual screening experiments against both HupD and HupM structures. For the sake of simplicity, now onward, the notions HupM and HupD will be used, respectively, for monomeric and homodimeric states of Hup. The results of virtual screening involving the LMW natural compound library are only presented and discussed in the main manuscript, whereas those with the HMW natural compound library are presented in the Supporting Information and discussed briefly in the main manuscript. A careful analysis of the outcomes of virtual screening experiments revealed different binding parameters and different docking orientations from different in silico molecular docking techniques. Figure 2A shows the top ten hit compounds ranked according to their highest binding energy obtained after different molecular docking runs. In order to highlight specific compounds in top ranked hit indices, we used different colors and visually analyzed the results (Figure 2A). One natural compound, that is, epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), was found in five hit indices and three compounds, that is, catechin gallate (CG), isomasticadienolic acid, and withaferin-A (WA), were found in four hit indices, whereas two compounds, that is, glycyrrhetinic acid (GrA) and protopine, were found in three hit indices. The binding energies of LMW ligands obtained from different molecular docking methods are tabulated in the Supporting Information, Table S1.

Figure 2.

(A) Top ten binding hits identified through AUTODOCK (top), VINA (middle), and Schrödinger glide docking using the extra-precision algorithm (bottom). The different colors are used to highlight specific compounds present in the top hit index. One natural compound, that is, EGCG was found in five hit indices, three compounds, that is, CG, isomasticadienolic acid, and WA, were found in four hit indices, whereas two compounds, that is, GrA and protopine, were found in three hit indices. (B) Stacked binding energy (in kcal/mol) obtained after computational screening of the LMW library of natural compounds against target structures of HupM and HupD receptors. Abbreviations used: AHP: anti-H. pylori; HupM: monomeric Hup; HupD: dimeric Hup; AD_BE: AUTODOCK binding energy; VINA_BE: VINA binding energy; GS: glide score, LID: internal ID of compound in Table 1.

Important to be mentioned is that in our previous study,44 the structural models of Hup were predicted using the free web-based protein structure prediction server named (PS)2v2,45,46 and the virtual screening was performed using AUTODOCK and VINA. In the present study, we used the YASARA homology model and also involved glide docking (in addition to AUTODOCK and VINA), so that any biasness in our findings can be avoided either due to homology modeling or molecular docking algorithms. The YASARA homology model of HupD when compared to the (PS)2v2 model both were found to share the overall structural fold and secondary structural elements as described above (see Supporting Information, Figure S2C,D).

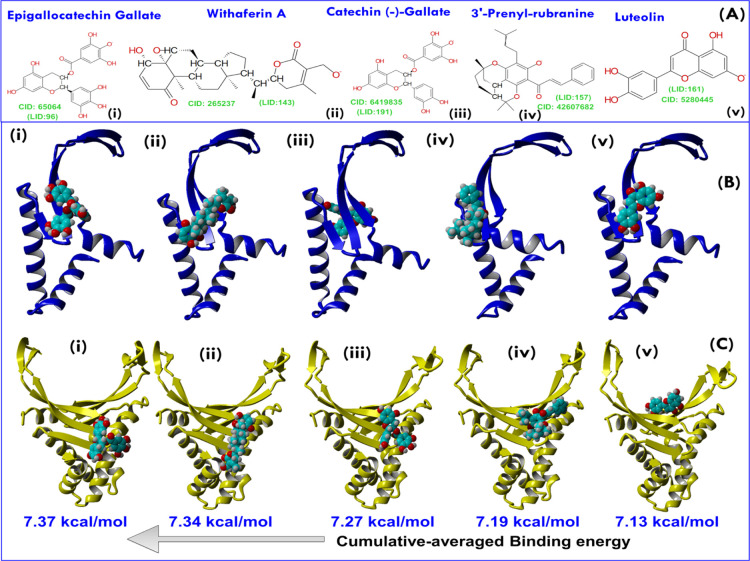

Further, we made another small exercise to find ligands binding most efficiently to Hup in general. For this, the binding energies of LMW ligands obtained from different docking algorithms were plotted in a stacked manner as shown in Figure 2B. For each ligand, six binding energies are plotted in different colors but in an additive manner (Figure 2A). The plot allowed us to index ligands according to their highest cumulative binding energy (CBE) value. Eventually, five natural compounds were shortlisted based on their highest CBE value—namely, EGCG, CG, WA, luteolin, and 3-prenylrubranine (3PR). The molecular structures of these five shortlisted lead compounds are shown in Figure 3A, and their best AUTODOCK-based docking poses in complex with the target receptors (HupM and HupD) are shown in Figure 3B,C, respectively.

Figure 3.

(A) 2D structure representations of five lead compounds selected based on the highest CBE score (see Figure 2). The corresponding PubChem ID of each compound is shown as CID, whereas the compound identity in the LMW library is shown as LID. (B) Best AUTODOCK poses of lead compounds—namely, EGCG, WA, CG, 3PR, and luteolin with HupM and (C) are the best AUTODOCK poses of lead molecules with HupD. Abbreviations used: CID: PubChem ID; LID: compound ID in the LMW library.

In Figure 3, the five ligands from left to right have been arranged according to their decreasing CBE value: that is, EGCG with the highest CBE value equal to 7.37 kcal/mol and then followed by CG, WA, 3PR, and luteolin with their respective CBE values equal to 7.34, 7.27, 7.19, and 7.13 kcal/mol (Figure 3). For each ligand, the CBE value was estimated as

| 1 |

Where BEAUTODOCKmonomer, BEVINA, and BEGlidemonomer are the binding energies of ligands docked against HupM using AUTODOCK, VINA, and Glide docking methods, respectively, whereas BEAUTODOCK, BEVINAdimer, and BEGlide are the binding energies of ligands docked against HupD using AUTODOCK, VINA, and Glide docking methods, respectively. However, clearly evident from Figure 2A is that out of the five shortlisted compounds, three compounds (EGCG, CG, and WA) were well consistent in top-hit indices. Particularly, the virtual binding efficacy of EGCG was not only found to be highest (Figure 2B) but seems to be deemed pertinent for further experimental testing owing to its presence in five out of six top-ranked hit indices (Figure 2A).

Rationale for Selecting EGCG for Further Experimental Testing

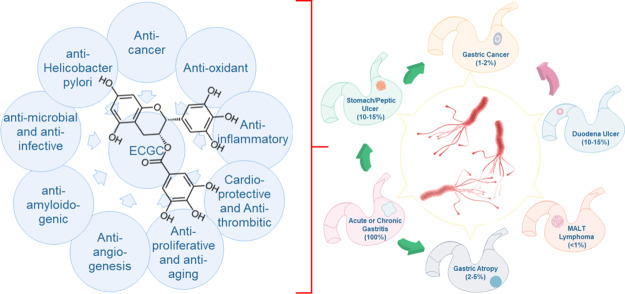

Since ancient times, green tea has been considered as a health-promoting beverage.47 EGCG is a major polyphenolic compound found in green tea leaves and accounts for 50–80% of the catechin. It is water soluble and has diverse medicinal properties (depicted in Figure 4) including anti-inflammation, antioxidative,48,49 anticancer activity,50 cardio-protective as well as antithrombotic activity,51,52 antitumor activity,53 antibiofilm activity,54 antibacterial/anti-infective activity,55,56 and, particularly relevant in the present context is, its potent AHP activity (with its MIC90 equal to 100 μg/mL).57 The gastro-protective activity of EGCG against H. pylori-infected gastritis has also been reported in Mongolian gerbil (considered a stable animal model of H. pylori-infection-induced gastric disease58). The important aspect of this study is to identify small molecules which may disrupt Hup dimerization or Hup–DNA binding interaction. A number of previous studies have demonstrated that EGCG inhibits protein dimerization/oligomerization59,60 and is also known to interact with DNA/RNA structures.61 These attributes of EGCG altogether derived our interest to perform further experimental testing of its binding interaction with protein Hup. For this, we used ligand-based NMR methods as described further.

Figure 4.

Reported biological and pharmacological activities of EGCG demonstrated in a series of clinical and preclinical studies and their implications in ameliorating the gastric pathologies caused by H. pylori.

In Silico Molecular Docking Experiments and MD Simulations

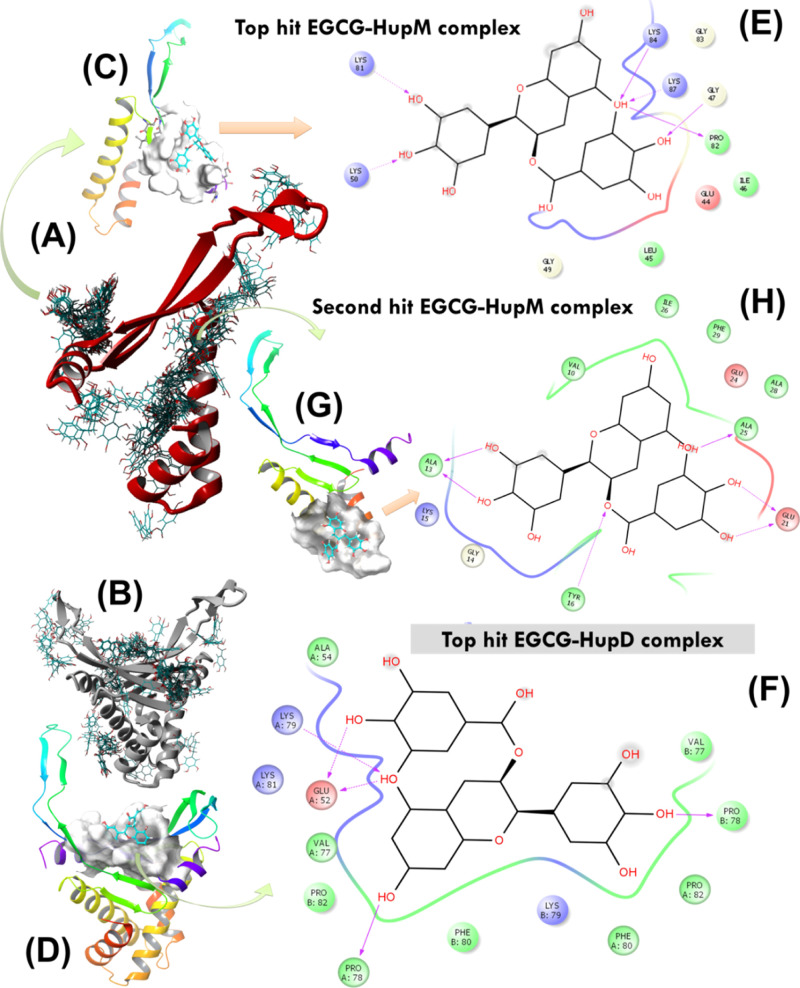

Before conducting experimental testing, the lead EGCG molecule was re-docked over HupM and HupD using the AUTODOCK molecular docking approach. In each case, 64 docking runs were performed (using default parameters in software program YASARA), and finally, all the docking conformations were clustered by ligand heavy-atom root mean square deviation (RMSD) with a cutoff of 5.0 Å62 (Figure 5A,B). The resultant highest energy docked conformations of EGCG with HupM and HupD were further evaluated and validated for their stability under biological conditions through performing long run MD simulation in an explicit water solvent. The cluster analysis resulted in 28 and 24 docked conformations of EGCG, respectively, over the protein surface of HupM and HupD (Table 2). In each case, the protein–ligand complex with highest binding energy (i.e. 8.28 ± 0.10 kcal/mol with HupD and 6.62 ± 0.39 kcal/mol with HupM) was found showing EGCG interaction with the C-terminal residues forming a DNA-binding saddle pocket (Figure 5C,D). The highest energy docked conformation of the EGCG–HupM complex was also found to contain the highest number of docking members (i.e. total 8, see Table 2) suggesting its high probability to exist in solution under near physiological conditions. For this highest energy complex between EGCG and HupM (Figure 5C), the contacting receptor residues were E44, L45, I46, G47, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, and K87 (Figure 5E). For highest energy docked conformation of the EGCG–HupD complex, the contacting receptor residues are E52, A54, V77, P78, K79, F80, K81, P82, *V77, *P78, *K79, *F80, and *P82 (note: the symbol * is used here for the second chain of HupD structure, Figure 5H). A careful analysis of the overall 64 docking poses of EGCG over HupM, however, revealed very high possibility of EGCG to bind to the dimerization interface of Hup as well (see Figure 5A). The second highest energy complex between EGCG and HupM (shown in Figure 5G) indeed represents the most probable binding pose of EGCG with HupM contacting through residues V10, A13, G14, K15, Y16, E21, E24, A25, I26, A28, and F29 (Figure 5H).

Figure 5.

(A,B) AUTODOCK molecular docking runs (N = 64) performed to search for potential EGCG binding sites over the protein surface of HupM and HupD. (C,D) Best docking poses of EGCG with HupM and HupD selected after cluster analysis based on highest binding energy of the complex. (E,F) 2D representation of molecular interaction for the ligand (EGCG) surrounded by contacting receptor residues. (G) Potential binding mode of EGCG with HupM selected after cluster analysis based on the second highest binding energy of the complex and the corresponding 2D representation of molecular interaction for the ligand (EGCG) surrounded by contacting receptor residues of HupM are shown in (H).

Table 2. After Clustering the 64 AUTODOCK Runs, the Following 28 and 24 Distinct Complex Conformations Were Found, Respectively, against HupD and HupMa.

| cluster (member) | BE (kcal/mol) | contacting receptor HupD residues |

|---|---|---|

| 1(1) | 8.23 ± 0.00 | E52, A54, V77, P78, K79, F80, K81, P82, V′77, P′78, K′79, F′80, P′82 |

| 2(4) | 7.63 ± 0.37 | K79, F80, K81, P82, G83, K87, E91, Q′56, K′59, V′77, P′78, K′79, F′80 |

| 3(3) | 6.83 ± 0.74 | E44, L45, I46, G47, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, T85, K87, Q88, N′2, K′3 |

| 4(2) | 6.98 ± 0.79 | K87, E91, Q′56, K′59, E′60, G′61, Y′70, K′71, T′72, E′73, K′75, V′77 |

| 5(6) | 7.63 ± 0.10 | L9, E12, A13, G14, K15, R′20, E′23, E′24, A′25, S′27, A′28, L31, A′32, T′35 |

| 6(10) | 7.42 ± 0.13 | E′44, L45, I′46, G′47, G′49, K′50, K′81, P′82, G′83, K′84, T′85, K′87 |

| 7(3) | 6.98 ± 0.88 | E44, L45, I46, G47, G49, K50, E52, K81, P82, G83, K84, T85, K87 |

| 8(2) | 7.23 ± 0.39 | M1, F6, L9, V10, E12, A13, K89, A′28, F′29, L31, A′32, E′34, T′35, A′36, K′39 |

| 9(3) | 6.65 ± 0.59 | V77, P78, K79, F80, K81, P82, V′77, P′78, K′79, F′80, P′82 |

| 10(4) | 6.63 ± 0.31 | E′44, L45, I′46, F′48, G′49, K′50, K′81, P′82, G′83, K′84, K′87 |

| 11(1) | 6.87 ± 0.00 | N2, E′44, L45, I′46, G′47, F′48, G′49, K′50, K′81, P′82, G′83, K′84, T′85, L86 |

| 12(1) | 6.81 ± 0.00 | E′44, L45, I′46, G′47, F′48, G′49, K′50, P′82, G′83, K′84, T′85, K′87, Q′88 |

| 13(2) | 6.62 ± 0.04 | Q56, K75, V77, P78, K79, F80, K81, F′80, K′81, P′82, K′87, E′91 |

| 14(1) | 6.66 ± 0.00 | E44, L45, I46, G47, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, T85, N′2, K′3 |

| 15(2) | 6.61 ± 0.01 | E52, A54, V77, P78, K79, F80, K81, P82, V′77, P′78, K′79, F′80, K′81, P′82 |

| 16(1) | 6.60 ± 0.00 | V77, P78, K79, F80, K81, P82, K′79, F′80, P′82 |

| 17(3) | 6.46 ± 0.11 | E55, Q56, K57, E73, D74, K75, R76, E′91, E′92, G′93 |

| 18(1) | 6.58 ± 0.00 | M1, G′40, E′41, S′42, E′44, K′50, E′52, T′53, A′54 |

| 19(1) | 6.39 ± 0.00 | L9, V10, E12, A13, K89, A′28, F′29, L31, A′32, E′34, T′35, S′38, K′39 |

| 20(2) | 6.30 ± 0.03 | E′44, L45, I′46, G′47, F′48, G′49, K′50, K′81, P′82, G′83, K′84, T′85, K′87 |

| 21(1) | 6.18 ± 0.00 | E73, D74, K75, R76, K′87, Q′88, K′89, E′91, E′92, G′93 |

| 22(1) | 6.08 ± 0.00 | G′58, E′60, T′69, Y′70, K′71, T′72, E′73, D′74 |

| 23(1) | 5.99 ± 0.00 | E44, L45, I46, G47, F48, G49, K50, G83, T85, N′2, K′3, A′4 |

| 24(2) | 5.79 ± 0.10 | E44, L45, I46, G47, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, K87 |

| 25(2) | 5.71 ± 0.13 | E91, E92, G93, G′58, K′71, T′72, E′73, D′74, K′75 |

| 26(1) | 5.60 ± 0.00 | K15, Y16, K′11, N′17, S′18, K′19, R′20, E′21, E′23, E′24 |

| 27(1) | 5.54 ± 0.00 | E91, E92, G93, E′55, E′73, D′74, K′75, R′76 |

| 28(1) | 5.02 ± 0.00 | K3, A4, I7, K19, R20, E23, E24, S27, A28, L31, A′13, I′46 |

| 1(8) | 6.62 ± 0.39 | E44, L45, I46, G47, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, K87 |

| 2(3) | 6.05 ± 0.65 | V10, A13, G14, K15, Y16, E21, E24, A25, I26, A28, F29 |

| 3(2) | 6.63 ± 0.07 | E44, L45, I46, G47, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, T85, K87 |

| 4(3) | 6.37 ± 0.29 | L37, S38, G40, T53, E55, D74, K75, R76, V77, P78 |

| 5(5) | 6.35 ± 0.09 | M1, N2, K3, F6, V10, A25, I26, F29, T30, L31, V33, E34, L45, F51 |

| 6(5) | 6.18 ± 0.34 | E44, L45, I46, G47, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, K87 |

| 7(1) | 6.40 ± 0.00 | T30, L31, V33, E34, T35, L37, S38, F51, V77, P78, K79, F80 |

| 8(4) | 6.08 ± 0.29 | F29, T30, L31, V33, E34, L37, S38, G40, F51, T53, R76, V77, P78, K79 |

| 9(7) | 6.24 ± 0.16 | E44, L45, I46, G47, F48, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, K87 |

| 10(1) | 6.03 ± 0.00 | K11, E12, A13, G14, K15, Y16, N17, S18, E21 |

| 11(1) | 5.98 ± 0.00 | E44, L45, I46, G47, F48, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, T85, K87 |

| 12(3) | 5.68 ± 0.20 | N2, K3, F6, L9, V10, A13, A25, I26, F29, T30, L45 |

| 13(1) | 5.85 ± 0.00 | F6, I7, L9, V10, Y16, A25, I26, A28, F29, T30, L45, F48, F51 |

| 14(2) | 5.62 ± 0.22 | L37, S38, K39, G40, T53, E55, D74, K75, R76, V77, P78 |

| 15(2) | 5.73 ± 0.02 | G58, E60, T69, Y70, K71, T72, E73, D74 |

| 16(1) | 5.68 ± 0.00 | K3, S27, F29, T30, L31, V33, E34, L37, S38, P78 |

| 17(1) | 5.65 ± 0.00 | F29, T30, L31, V33, E34, L37, L45, F51, E52, P78, K79, F80 |

| 18(3) | 5.34 ± 0.24 | F48, T85, L86, K89, V90, E92, G93, K94 |

| 19(6) | 5.29 ± 0.23 | K3, F6, A25, I26, F29, T30, V33, E34, F51 |

| 20(1) | 5.55 ± 0.00 | F29, T30, V33, E34, L37, S38, L45, F51, P78, K79, F80 |

| 21(1) | 5.55 ± 0.00 | E44, L45, I46, G47, F48, G49, K50, K81, P82, G83, K84, T85 |

| 22(1) | 5.36 ± 0.00 | F6, F29, L45, I46, G47, F48, G49, F51, T85, L86, K89, V90 |

| 23(1) | 5.31 ± 0.00 | M1, F6, L9, V10, A13, A25, I26, F29, T30, L45, F48 |

| 24(1) | 4.67 ± 0.00 | G61, K62, V63, K68, T69, Y70, K71, T72, E73 |

The clusters in each group differ by at least 5.0 Å heavy atom RMSD after superposing on the receptor. The cluster conformations sorted by binding energy [more positive energies indicate stronger binding, and negative energies mean no binding].

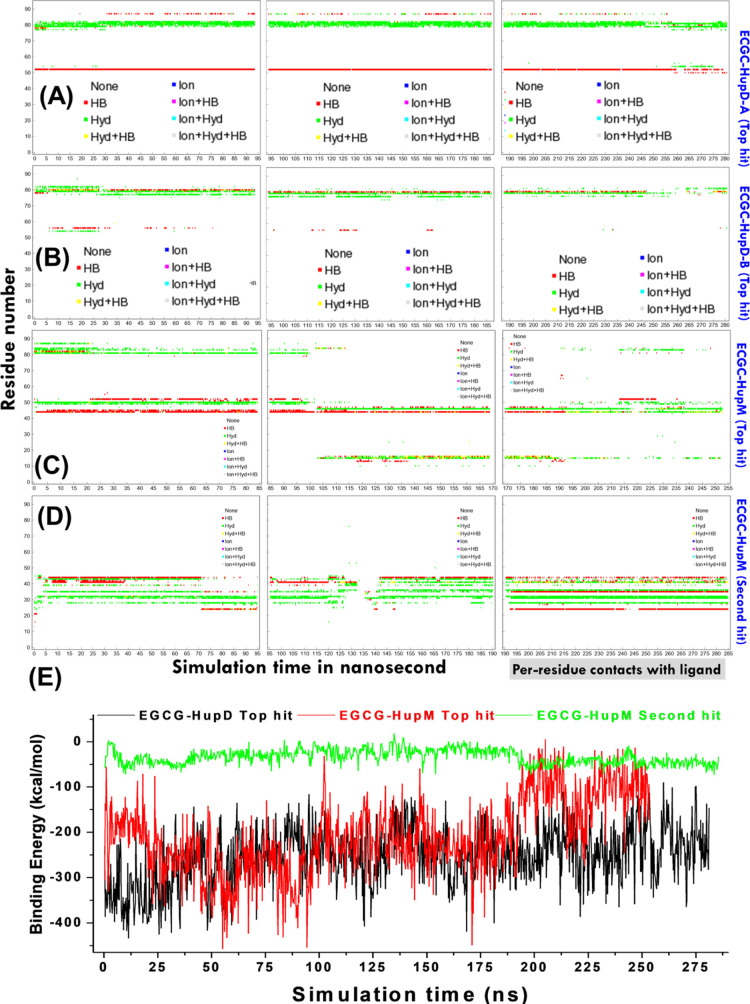

Further, these top indexed docked conformations selected based on their highest binding energies were subjected to long-run MD simulation studies to get more insights into the protein conformation, fluctuations, and interaction of protein’s atoms with EGCG under relevant biological conditions. The MD simulations take into account solvation and thermal motion and allow the physical movement of all atoms and molecules in the simulation system and thus help to prove the free energy changes of the overall system over the simulation time. Further, the MD simulations allow the identification of persistent molecular interactions of a small-molecule ligand with its target receptor protein. The MD trajectories obtained for different docked conformations were analyzed, and the complex stability is evaluated by profiling binding energy of the protein–ligand complex and per-residue contacts formed by Hup with ligand EGCG as a function of simulation time (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Plots showing the types of binding contacts formed by receptor residues with the ligand as a function of simulation time. For chain-A and chain-B of HupD, the plots are shown in (A,B), respectively, whereas for HupM, the plots are shown in (C,D), respectively, for first and second top-hit docked conformations of EGCG. Shown here are three types of contacts: ionic interactions (in blue), hydrophobic contacts (in green), and hydrogen bonds (in red). Also mixtures of these three colors can show up if a certain residue is involved in more than one type of contact with the ligand [see plot legend]. (E) Plot showing profiling of ligand energy of binding with HupD and HupM structures evaluated as a function of simulation time using YASARA macro named “md_analyzebindenergy.mcr”. Note that the values estimated are often larger than the expected binding energy values as the calculation in YASARA does not include intermolecular vdW interaction energies.

Additionally, we also evaluated other structural and conformational features such as comparison of complex structures before and after the MD simulation, time profiling of the total potential energy of the simulation system, number of hydrogen bonds between the solute and solvent, protein secondary structure content, residue-wise secondary structure, RMSD, root mean square fluctuations (RMSF), radius of gyration (Rg), ligand conformation RMSD after superposing on the ligand, number of contacts per residue in the protein, ligand movement RMSD (measured as ligand heavy atom RMSD after superposing the receptor on its reference structure), and ligand conformation RMSD after superposing on the ligand plotted as a function of simulation time (see Supporting Information, Figures S4–S13). Figure 6A,B shows the per-residue contacts made, respectively, by chain-A and chain-B of HupD with EGCG. Figure 6C shows the per-residue contacts made by HupM with EGCG during MD simulation performed with the highest energy complex (shown in Figure 5C), whereas Figure 6D shows the per-residue contacts made by HupM with EGCG during MD simulation performed with the second highest energy complex (shown in Figure 5D). Figure 6E shows the binding energy of ligands plotted as function of simulation time (for which more details can be seen here44).

The various results based on MD simulation trajectory analysis are summarized below:

-

(a)

Structural changes and the extent of conformational fluctuations are relatively higher in HupM compared to HupD as evident from Figures S5–S7 comparing the various structural and conformational features of HupM and HupD in their ligand-free form (see the Supporting Information) suggesting that dimerization provides structural stability to Hup in solution.

-

(b)

The binding of EGCG to the dimerization interface of HupM leads to significant change in the overall protein conformation and secondary structure content of HupM compared to its top-hit binding mode with EGCG (see Supporting Information, Figures S8–S10). This kind of postbinding conformational changes may impact the Hup dimerization in solution.

-

(c)

The prolonged persistence of per-residue contacts made by HupM with EGCG in its second highest energy complex (Figure 6D,E) further suggested that the binding interaction of EGCG with the DD to be fairly stable. This is further corroborated by the relatively limited movement of the ligand with respect to its binding site residues (see Supporting Information, Figure S4G).

-

(d)

Compared to the free form of HupD, the binding of EGCG to HupD does not cause much change in the overall protein conformation and secondary structure content of protein HupD (see Supporting Information, Figures S11–S13) suggesting a fairly strong and stable binding pose of EGCG with the HupD state as well.

-

(e)

For top binding energy complexes of EGCG with HupM and HupD, the EGCG binding to HupD seems to be fairly stable as inferred from prolonged persistence of contacts made by HupD residues with the ligand (Figure 6A,B vs Figure 6C) and the limited movement of the ligand from its docking site (see Supporting Information, Figure S4E vs Figure S4F).

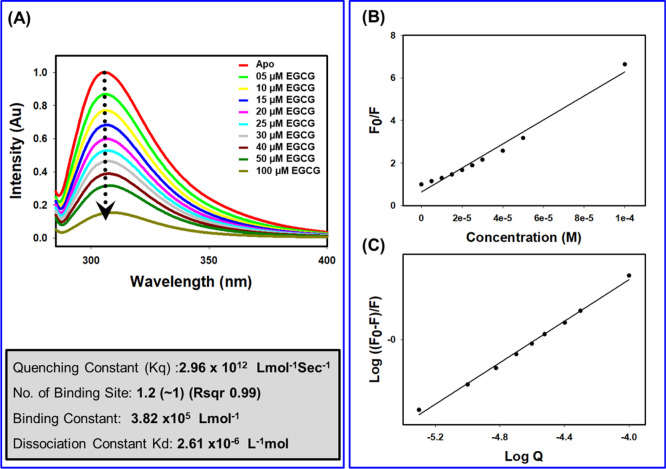

Fluorescence Quenching of Hup by EGCG

We started experimental testing of Hup–EGCG binding interaction employing the fluorescence quenching (FQ) method as explicitly described previously.44,63 As the Hup amino acid sequence does not contain any tryptophan residue, the recorded fluorescence spectra of protein Hup shown in Figure 7 represented the emission spectra of phenylalanine and tyrosine (Phe6, Tyr16, Phe29, Phe48, Phe51, and Phe80). Figure 7A shows that gradual addition of EGCG causes a dramatic decrease of the fluorescence signal of protein Hup hinting toward a strong binding interaction between Hup and EGCG. Following the details described previously,44 the quenching data of the Hup protein upon addition of the ligand was fitted to the Stern–Volmer equation (Figure 7B) and double logarithmic modification of the Stern–Volmer relationship (Figure 7C). This allowed us to quantify the binding parameters including the number of binding sites (n) equal to 1.2 (∼1, r = 0.99), binding constant equal to 3.82 × 105 L mol–1, and a dissociation constant equal to 2.61 μM.

Figure 7.

FQ of the Hup protein upon binding of EGCG. (A) Tyrosine fluorescence spectra of Hup (40 μM) in the absence and presence of EGCG at different molar concentration (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 40, 50, and 100 μM). (B) Stern–Volmer plot for the FQ of the Hup by EGCG where FQ values of the H. pylori Hup at an emission wavelength of 306 nm are plotted against the EGCG concentration. The filled circles are experimental data points. The curve was obtained by least-squares fitting to the results, yielding a quenching constant (Kq). (C) Double logarithmic Stern–Volmer plot. The plot is linear fit, wherein the slope corresponds to the number of binding sites and the yielded constant is equivalent to binding constant (0.38 μM in this case).

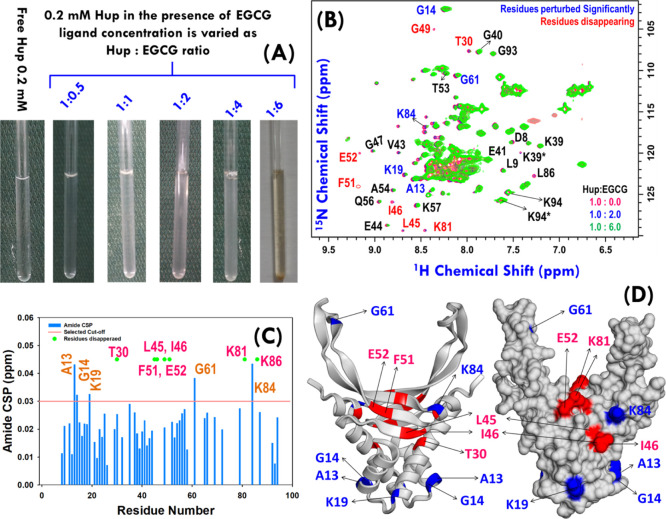

NMR Investigations of EGCG Binding with Hup

Over the decades, NMR spectroscopy has flourished dramatically—both in technological and methodological fronts—and over the past few decades, it has also become a valuable tool to investigate protein–ligand binding affinities in the nanomolar to millimolar regime.64,65 There are several NMR-based approaches reported in the literature which can be used for studying binding of ligands to protein targets; however, depending upon the molecular species to be probed, these are classified into two categories: (a) protein observed methods and (b) ligand observed methods.65−69 The particular advantages of NMR are its ability to provide information on binding affinity between ligands and their target protein(s) as well as to provide valuable insights into the protein conformational changes that plausibly occur upon binding to their ligand(s).65 The simplest yet most utilized approach for studying molecular interactions by NMR exploits amide shift differences between free and bound protein targets in two-dimensional (2D) 1H–15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) or heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation (HMQC) spectra of the target protein upon titration with a ligand.70,71 The approach is commonly known as chemical-shift mapping68,69 and we also tried this method to map the binding site of EGCG on Hup structures. For this, the uniformly 15N labeled Hup protein sample of nearly physiological relevant concentration (i.e. ∼0.2 mM) was prepared and titrated with the EGCG sample (20 mM stock solution, Figure 8A). To achieve adequate sensitivity at low concentration, the 15N SOFAST-HMQC spectra were recorded on free and bound states of proteins varying the EGCG concentration in the (protein–ligand) ratio of 1:0.5, 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:6 (Figure 8A). The amide correlation spectra of proteins in their free and bound states were overlaid for visual inspection of chemical shift perturbations (CSPs) (Figure 8B). To identify the resonances with substantial shifts upon binding to EGCG, a CSP map has been plotted using 50 unambiguous resonances (Figure 8C). CSP results suggested that residues A13, G14, K19, I46, G61, and K84 have shown significant perturbations (greater than 0.03 ppm). The progressive addition of EGCG also resulted into the successive disappearance of some of the amide cross-peaks corresponding to residues T30, L45, F51, K81, and L86. Except for residue T30, the majority of these residues were found on the DNA binding surface (Figure 8D) and partly do match with the EGCG binding site on Hup predicted using the AUTODOCK-based molecular docking approach (see Figure 5).

Figure 8.

(A) Uniformly 15N-labeled Hup sample (concentration ∼ 0.2 mM) titrated with EGCG stock solution of concentration 20.0 mM. (B) Overlay of 1H–15N SOFAST-heteronuclear multiple quantum correlation (HMQC) spectra of free Hup protein (red) and Hup containing EGCG: blue and green spectra represent the protein to ligand ratio equal to 1:2 and 1:6, respectively. The residues showing significant CSP from the free Hup protein are highlighted with blue color labels, and those exhibiting significant loss of the amide cross-peak signal are highlighted with red color labels. (C) CSP map depicting the change in the chemical shift values for 49 ambiguous cross-peaks of the Hup protein. The solid radish pink line represents the cutoff CSP value (∼0.03 ppm). (D) Homodimeric structure of the H. pylori Hup protein (left: ribbon diagram and right: surface structure); the perturbed and disappearing residues are shown in blue and red colors. Note the residues labeled in the black text are shown to highlight the assignment of some of the residues, where asterisk symbol “*” represents the peak corresponding to an alternative conformation. “Photograph courtesy of “Ritu Raj”. Copyright 2020.”

To be mentioned here is that the addition of EGCG to Hup protein solution resulted in a biochemical reaction and the complex solution became brown turbid in color as well evident from Figure 8A. The visual change in the solution color clearly suggested that the EGCG is reacting with Hup mediated through some molecular interaction mechanisms. Considering this limitation, we decided to estimate the binding parameters through performing the experiments at very low concentrations of protein Hup, that is, as low as 2–20 μM. For this, we employed ligand-observed NMR approaches where the NMR titration experiments are performed to probe the change in signal intensity (or linewidth), chemical shift, and relaxation rates as a function of changing protein concentration.72 Compared to chemical shift changes induced by protein binding, the changes in the signal intensity (or linewidth) and in relaxation rates are more prominent and easy to quantify.67,72 Therefore, in this study, we used NMR methods which allow probing change in linewidth and relaxation parameters. The NMR titration experiments were performed by varying the Hup protein concentration (in steps of 4.0 μM, as 0.0, 4.0, 8.0, 12.0, 16.0, and 20.0 μM; the sample preparation details are given in Supporting Information, Table S3). However, the EGCG concentration is kept constant at 100 μM (by preparing it in bulk) to avoid sample-to-sample variability of the ligand NMR signal.

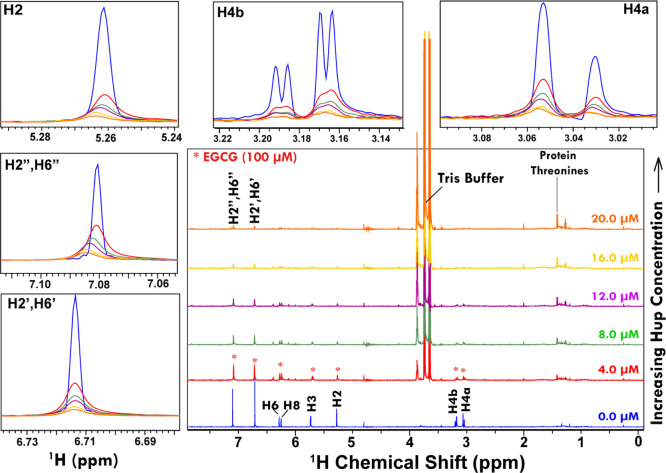

Figure 9 shows the one-dimensional (1D) 1H ZGESGP spectra recorded on 100 μM solution sample of EGCG with progressively increasing concentration of protein Hup. Clearly evident from the stacked spectra is that the addition of Hup leads to decrease in the signal intensity of EGCG resonances. For making visual inspection, the spectra from NMR titration experiments were overlaid and distinct spectral regions were zoomed in separate boxes (annotated according to peak assignments: H4a, H4b, H2, H2′/H6′ and H2″/H6″). It is clearly seen that the NMR signals of the EGCG sample of 100 μM concentration get saturated (i.e. decrease to a level of more than 80%) by the addition of Hup at concentration 20.0 μM suggesting that the binding interaction between EGCG and Hup is fairly strong.

Figure 9.

Stacking of 1D 1H ZGESGP NMR spectra of 100 μM EGCG recorded at 300 K using 800 MHz NMR spectrometer. The NMR spectra in blue represent free ligands (i.e. in the absence of Hup). The progressively decreasing (broadening of) NMR signals of EGCG upon increasing Hup concentration (4.0, 8.0, 12.0, 16.0, and 20.0 μM) clearly suggested that the ligand EGCG is binding strongly to protein Hup. The selected spectral regions in overlay mode are zoomed for visual inspection of the relative changes.

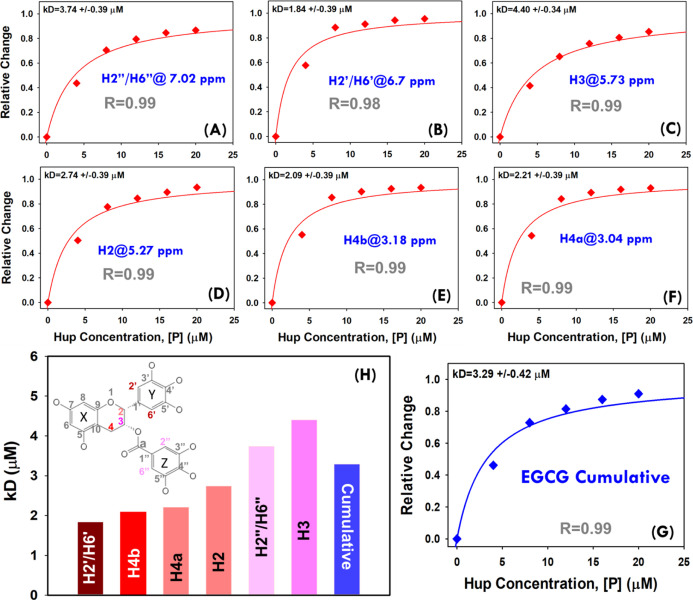

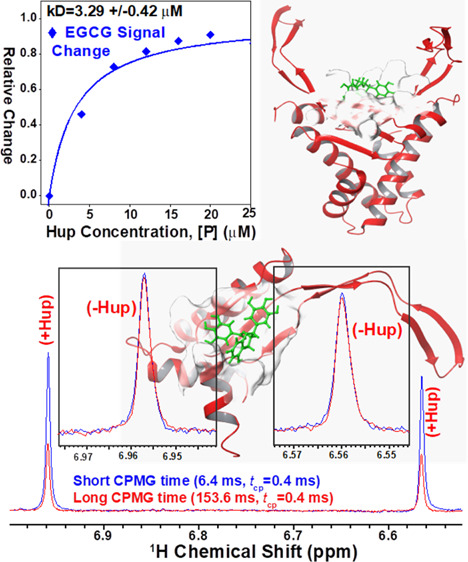

The NMR titration spectra shown in Figure 9 were further used to generate the saturation binding curves (Figure 10A–F). For this, the relative decrease in signal intensity is plotted as a function of protein concentration (raw data is provided in Supporting Information, Table S4A). These saturation binding curves for different EGCG peaks were then fitted to the standard hyperbolic equation (eq 2) to derive dissociation constant values. For estimating the average dissociation constant value, the cumulative change in the signal for all the EGCG peaks was used to generate the saturation binding curve (see raw data in Supporting Information, Table S4B) and then fitted to the hyperbolic equation which resulted in an apparent dissociation constant equal to 3.29 ± 0.42 μM (Figure 10G). This value is found to be nearly comparable to that derived from the FQ method, that is, 2.61 μM. However, the small difference may be attributed to differential methods employed to probe the binding parameters. In FQ experiments, the changes in the cumulative fluorescence signal of the protein are probed, whereas the changes in the ligand signals have been probed in the NMR titration experiments. In our virtual screening experiments involving molecular docking methods AUTODOCK and VINA (Figure 2A), the compound GrA was also found to be present in the panel of top ten compounds having highest binding energy for docking with Hup. Recently, a study from our laboratory reported the apparent dissociation constant equal to 36.6 ± 1.5 μM (based on NMR titration experiments) for binding interaction between GrA and Hup.44 This clearly suggested that the solution binding efficacy of EGCG with Hup is fairly strong compared to that of GrA with Hup as also evident from their averaged CBE obtained from molecular docking experiments, that is, 7.37 and 6.88 kcal/mol, respectively, for EGCG and GrA (see Supporting Information, Table S1, ID = 25).

Figure 10.

(A–F) Hyperbolic (saturation binding) curves showing a relative change in NMR signals of EGCG resonances (θ = I0 – I/I0) as a function of protein concentration (0.0, 4.0, 8.0, 12.0, 16.0, and 20.0 μM). The dissociation constants (kD values) based on individual EGCG peaks were estimated by fitting each individual saturation binding curve to hyperbolic eq 2 (shown in main paper). (G) The cumulative saturation binding curve for interaction between EGCG and Hup and its fitting to hyperbolic eq 2 are used to estimate the apparent dissociation constant (kD). (H) Bar plot showing a progressively increasing dissociation constant for different EGCG signals and the cumulative value derived from the average change of signal intensity. The 2D molecular structure of EGCG highlighted for protons showing relevant hyperbolic saturation binding curves as per the colors of their respective bars in the graph (H).

The vertical bar-plot in Figure 10H shows the dissociation constants (in an increasing order) for different 1H resonances of EGCG. The vertical bars are colored differentially: dark red for lower kD values and dark blue for higher kD values. The inset in Figure 10H shows the 2D molecular structure of EGCG with atomic mapping of the dissociation constant as per the color coding of respective bars therein. Consistent to molecular docking poses shown in Figure 5, the trihydroxy aromatic moieties (“Y” and “Z”) were found to be more affected compared to the dihydroxy-chroman moiety (“X”) of EGCG suggesting that its binding to Hup is possibly mediated through trihydroxy aromatic moieties.

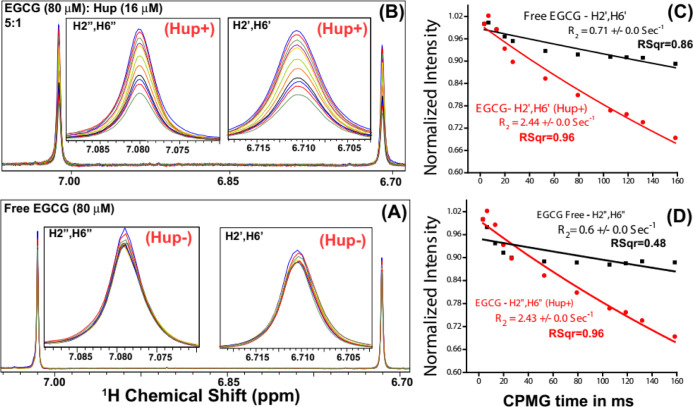

Next, the binding of EGCG with Hup was studied using the relaxation editing method for which the optimal range of dissociation constant is 0.1 μM to 1.0 mM.69 Generally, relaxation editing experiments are performed in the presence of proteins and involve comparison of the ligand signal in NMR spectra recorded with short and long T2 relaxation delays.69,73,74 Typically, the Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) sequence is used to achieve relaxation-editing in an NMR experiment, which additionally allows for the measurement of T2 relaxation time by following the signal decay as a function of CPMG time.64 The selection of relaxation delay, however, depends upon the binding efficacy. The relaxation of high affinity ligands is more strongly influenced upon binding; therefore, long CPMG times are used, whereas longer relaxation delays are recommended for weakly binding ligands. As there is fairly strong binding of EGCG with Hup, the NMR sample for relaxation measurements on the ligand (assuming there is nearly one binding site) was prepared with the Hup to EGCG ratio equal to 1:5.73

Figure 11A shows an overlay of 1D 1H CPMG NMR spectra of the solution sample of EGCG (100 μM) recorded in the absence of protein Hup, and Figure 11B shows those recorded in the presence of 16 μM Hup. It is clearly evident that the NMR signals of EGCG in the presence of Hup attenuate significantly and progressively with increasing relaxation delay time, whereas in the absence of protein Hup, the signal attenuation found to be very small. This clearly suggested that there is transfer of relaxation properties from the Hup receptor to EGCG due to their interaction. The signal attenuation may partly be attributed to line broadening induced by the exchange process between the free and bound states of ligands. To corroborate the line broadening effect, transverse-relaxation rates (R2 = 1/T2) of EGCG (100 μM) were measured in the absence and presence of Hup (16 μM) and the 1H relaxation decay profiles are shown in Figure 11C,D. As R2 depends on rotational diffusion (τc), the binding interaction between the ligand and receptor tends to decrease the rotational diffusion of the ligand involved in interaction with the receptor protein; however, for very weak (kD > 100 mM) and very strong binding ligands (kD < 10 μM), their R2 rates are identical to free ligands.72 For weak intermolecular interactions (kD values in the mM to μM range), the R2 relaxation property of the receptor protein gets partly transferred to the interacting ligand rendering its increased R2 rates.73,74 As expected, the R2 rates of an EGCG increase in the presence of the Hup protein (2.44 ± 0.0 s–1 for H2′/H6′ and 2.43 ± 0.0 s–1 for H2″/H6″) compared to its R2 in the absence of Hup (0.71 ± 0.0 s–1 for H2′/H6′ and 0.6 ± 0.0 s–1 for H2″/H6″). The evident increase in R2 values of EGCG resonances clearly indicated further that the binding interaction between EGCG and Hup is fairly strong. To be mentioned here is that the relaxation data recorded with short CPMG times (0.2–1.0 ms) is used to probe fast time scale motions following data fitting to single exponential decay. However, in Figure 11C,D, the magnetization recovery plots used for estimating the R2 are significantly deviated from single-exponential recovery as evident from their regression coefficient values significantly lower than the desired value (i.e. R2 should >0.95), and this might be attributed to conformational exchange exhibited by 1H resonances of free EGCG in solution on the slow (microsecond to millisecond) time scale.75,76

Figure 11.

(A,B) Intensity profiling of two major EGCG NMR signals: one at δ (6.71 ppm) corresponding to EGCG resonances H2′/H6 second at δ (7.08 ppm) corresponding to EGCG resonances H2″/H6″. Compared to NMR signals of free EGCG (A), the signal attenuation (i.e. decreasing signals with increasing CPMG time) is relatively more in the presence of Hup (A) clearly indicating the binding interaction between GrA and Hup. (C,D) Apparent 1H transverse relaxation (T2) times of EGCG resonances (H2′/H6 and H2″/H6″) compared in the absence (black) and presence of protein Hup (red) (for protein to ligand ratio ∼16:∼80 μM = 1:5).

To be mentioned here is that the results presented in this paper are based on virtual screening of the LMW library of natural AHP compounds (with MW < 500 Da) against the target protein Hup; however, the results of virtual screening of the HMW library of natural AHP compounds (with MW > 500 Da) against the target protein Hup are presented in Appendix IV of the Supporting Information (Table S5 and Figures S15 and S16). The top three hit compounds identified based on virtual screening experiments are gallagic acid (LID: 33, 34; CBE = 9.45 kcal/mol), luteolin-7-O-β-d-diglucuronide (LID: 14; CBE = 8.92 kcal/mol), and 1,2,3,6-tetra-O-galloyl-β-d-glucose (LID: 3; CBE = 8.68 kcal/mol) (see Supporting Information, Table S5 and Figure S15). The highest energy GLIDE docking conformations of gallagic acid with HupD and HupM are shown in the Supporting Information (see Figure S16).

Conclusions

Nucleoid associated proteins (NAPs) in bacteria play important roles in nucleoid compaction, maintaining DNA functional morphology and regulating various DNA transactions such as replication, recombination, repair, and transcription.39,77 Hup is one of the most abundant NAPs expressed by H. pylori, and the protein additionally plays an important role in protecting the pathogen from acidic and oxidative stress conditions through modulating gene expression in response to varying external conditions.38,78 Hup—being an important secretory protein—is also known to contribute in pathogeneses of H. pylori through subverting the host immuno-inflammatory response.4,8 Overall, Hup—being involved in various important cellular functions—plays a strategical role for H. pylori to evade, escape, and colonize persistently under the hostile environment of the human gastrointestinal tract.36,79,80 Therefore, targeting the molecular interactions involving Hup would definitely impact the survival of the pathogen. The present study was designed to prepare a library of natural compounds (belonging to alkaloids, terpenoids, thiophenes, phenolics, etc.) reported in the literature for their antibacterial activity against H. pylori (Table 1). The resulting library is then used to identify LMW compounds (with MW < 500 Da, referred here as LMW compound library) binding efficiently with H. pylori Hup. A recent study from our laboratory reported the existence of dynamic equilibrium between the HupM and HupD states of protein Hup under near biological conditions of salt, temperature, and pH.37 Therefore, natural compounds were virtually screened against both HupM and HupD structures. For this, the 3D structure of HupD was first generated using YASARA homology modeling experiment. The resulting dimeric model was then subjected to energy minimization in an explicit aqueous solvent environment, and subsequently, the chain-B of the dimeric model was extracted as the HupM structure and energy minimized in the explicit aqueous solvent environment also. The LMW compound library containing AHP molecules was then virtually screened against both HupM and HupD structures using in silico molecular docking methods (such as AUTODOCK, VINA, and Glide). Eventually, five compounds were identified as lead binding hits based on their highest CBE (ranging from 7.37 to 7.13 kcal/mol) (Figure 3). These lead compounds (namely EGCG, WA, CG, 3PR, and luteolin) were all found binding efficiently to the DNA binding interface of Hup (Figure 3). Of these five compounds, EGCG was rationally selected for further in silico and experimental evaluation of its binding interaction with Hup. The selection implies its highest binding energy with Hup, highest AHP activity, as well as other valuable health benefits including its gastro-protective effects (Figure 4). In silico molecular docking studies involving 64 AUTODOCK runs further validated the virtual screening results, and it was found that EGCG makes important interactions with the DNA binding interface of Hup (Figure 5). The best docking poses of EGCG with HupM and HupD were further evaluated for their stability in explicit water solvents using long run MD simulations. The trajectory analysis of MD simulation data (especially, the time profiling of per-residue contacts with the ligand and ligand binding energy, Figure 6) revealed that the EGCG–HupM complex (second hit) is relatively more stable in solution compared to the EGCG–HupD complex as inferred from the highest binding energy of the HupM–EGCG second hit complex. Largely, the EGCG binding to Hup was found to be driven by hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding interactions as evident from ligand contact maps (Figure 5) and per-residue contacts of the protein with the ligand (Figure 6). The binding interaction between EGCG and Hup was finally tested experimentally using FQ and NMR-based approaches (Figures 7–9). The residues exhibiting significant amide CSPs or signal decay upon EGCG addition (Figure 8) were exquisitely found in concordance with EGCG binding sites predicted using the molecular docking approach (Figure 5). The fluorescence and NMR titration experiments resulted in comparable equilibrium dissociation constants (kD) for binding between EGCG and Hup equal to 2.61 and 3.29 ± 0.42 μM, respectively (Figures 7 and 10C). Compared to free EGCG, the significantly increased transverse relaxation rates (R2) of EGCG in the presence of Hup further confirmed that the binding between EGCG and Hup is fairly strong (Figure 11). However, for in vivo validation of these results, future investigations are required to elucidate the intervention effect of EGCG on nucleoid compaction and coccoid formation of H. pylori under acidic stress conditions. Compared to normal (untreated) H. pylori cells, the H. pylori cells treated with EGCG should show impaired nucleoid compaction and will fail to form coccoid after an abrupt decrease in surrounding pH.

Materials and Methods

Generation of the Natural Compound Library

Totally, 159 natural compounds with promising AHP activity were identified and have been compiled in Table 1. The molecular structures of these compounds (in sdf format) were downloaded from the PubChem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).81 After preparing the collective compound library, the molecular structures in the database were energy minimized and geometry optimized employing the LigPrep module (as per the parameters displayed in Supporting Information, Figure S1) of the Maestro molecular modeling suit (Schrödinger, LLC: New York, NY).82,83 The geometry optimization with the OPLS3 force field involved addition of hydrogen, bond order and bond angles corrections, 2D to 3D conversion, tautomers, stereochemisteries, ring conformation optimization, and finally energy minimization. The geometry optimization was performed in two steps: first for compounds with MW less than 500 Da and second for compounds with MW equal to higher than 500 Da. The first step led to a library containing 246 conformations referred here as the LMW library and second step led to a library containing 42 conformations referred here as the HMW library.

Homology Modeling Using YASARA

As there is no experimental X-ray or solution NMR structure of H. pylori Hup in the international protein data bank (PDB) repository (https://www.rcsb.org), a high-resolution structure of homodimeric Hup protein was modeled using software program YASARA (http://www.yasara.org). The amino acid sequence of Hup was used as an input (in FASTA format), and the default homology modeling macro of the YASARA structure was executed to generate the dimeric model of Hup.84 In order to increase the accuracy beyond each of the contributors, the best parts of top 5 models were selected and combined to obtain a hybrid model. The resulted hybrid model is also used to extract the monomeric structural model of Hup. To minimize the number of energetically unfavorable structural features, both HupM and HupD structures were subjected to refinement (relaxation) by all-atom MD simulations in an explicit water solvent using YASARA Server for Energy Minimization (http://www.yasara.org/minimizationserver.htm)85 and the hydrogen bonding network was optimized using the YASARA force field86 (results are depicted in Supporting Information, Figures S2 and S3).

Virtual Screening

Virtual screening serves as an efficient prototype for filtering (or indexing) compounds binding efficient to the target protein active site. Virtual screening was first carried out using software program YASARA which allows screening of compound library based on two molecular docking algorithms employing AUTODOCK and VINA. The LMW compound library is further screened using Schrödinger software suite (Maestro 10.5), and scoring calculations were performed using the glide XP method. For glide docking, the protein receptor (Hup structure) was prepared using the “Protein Preparation Wizard” where the protein was first processed to assign bond orders, creating zero bond orders, addition of hydrogens, and deletion of water molecules having distance more than 5 Å from protein molecules. Next, the protein structure was optimized through modifying orientation of functional groups and energy minimized using the OPLS3 force field. A receptor grid was generated using the “Receptor Grid Generation” module where the van der Waals (vdW) radii of the receptor protein was scaled by 1 Å along with a partial charge cut-off of 0.25. After grid generation, a rigid receptor protein was docked with flexible energy minimized and geometry optimized 3D ligand structures using the XP algorithm of Glide Docking. After docking, top binding ligands were screened on the basis of the Glide score (also known as G-score). The molecular representations of Hup–ligand complexes were created using modalities of the YASARA structure and Maestro (Schrödinger) software, whereas the receptor–ligand interactions were visualized as 2D ligand interaction diagrams generated exclusively using Maestro application of Schrödinger software.83

MD Simulations

The lead compound identified based on virtual screening was redocked using AUTODOCK (64 runs performed each for monomeric and homodimeric structures of Hup) and the highest energy docked conformations were further evaluated for solution stability under biological conditions through performing MD simulations in an explicit water solvent using YASARA Dynamics software (version 19.12.14.W.64).87 The explicit details are presented in the Supporting Information, Appendix I. The MD simulations and the subsequent trajectory analysis were performed using the Dell Precision T7810 Tower Workstation (having 16 GB of RAM, 2.40 GHz Intel Xeon Processor E5-2630 v3 and 64 bit Windows 10 operating system).

Cloning of Recombinant Hup Protein, Expression, and Purification

For ligand binding studies using NMR experiments, the recombinant Hup protein of H. pylori was expressed and purified following the protocol reported previously.4,37 The purified protein was concentrated to about 200 μM in sodium phosphate buffer (of strength 50 mM and pH 6.5) containing NaCl salt equal to 200 mM. The resulting solution sample of Hup protein was divided into multiple aliquots of 0.5 mL each in 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tubes. The protein sample in each aliquot was lyophilized and later on used for NMR titration experiments by dissolving each sample aliquot in 0.5 mL of deuterated water (D2O, 99.9%).

NMR Titration Experiments

For studying protein–ligand interactions in solution, we employed simple ligand-based NMR approaches which involve the comparison of the NMR peak linewidth (or signal intensity) of ligands and/or their relaxation rate in the receptor-free and bound state.67,68 A series of 1D 1H NMR spectra were acquired on the solution sample of the ligand by titrating with protein, and a relative change in signal intensity data as a function of protein concentration was used to estimate the equilibrium dissociation constant for binding between EGCG and Hup. The NMR experiments were recorded at 300 K using a 800 MHz FT-NMR spectrometer (Avance-III) equipped with a Cryogenic Triple resonance TCI probe (Bruker BioSpin GmbH, Germany). The 1D 1H NMR spectra were recorded using Bruker standard library pulse-program ZGESGP following acquisition parameters: recycle delay equal to 4.0 s, 1H spectral width of 20 ppm (∼16,000 Hz), number of scans equal to 128, and free induction decay (FID) data points 32k. The acquired FIDs were multiplied by an exponential function (line broadening was set to 0.3 Hz) and zero-filled with 64k data points. After zero-filling, each FID was Fourier-transformed using TopSpin software (v3.6, Bruker BioSpin, Germany) and the resultant spectra were then manually phased and baseline corrected. For NMR titration experiments, the EGCG sample of concentration ∼100 μM was prepared in 100% D2O and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. The sample volume of 600 μL was filled in a 5 mm NMR tube (Wilmad Glass, USA). A series of 1D 1H ZGESGP NMR spectra were recorded on the EGCG sample titrated with protein Hup varying concentration from 0.0 to 20 μM in steps of 4.0 μM (sample preparation details are provided in Supporting Information, Table S2). Assuming Hup predominately exists as a monomer at low protein concentration,44 the concentration of the protein sample was estimated according to the Hup monomeric state (with extinction coefficient 2980 mol–1 cm–1, at 280 nm, MW ∼ 10.38 kDa). The signal-to-noise ratio was estimated for different NMR peaks of EGCG, and the data is tabulated in the Supporting Information (Table S3A,B). The resultant intensity profiles were used to generate binding isotherms by plotting a relative increase in complex concentration (also referred to as the degree of binding, θ) as a function of protein concentration. The resultant binding isotherms (also known as saturation binding curves) were then fitted to well-known one site hyperbolic eq 2(88) to estimate the equilibrium dissociation constant (kD) for binding between EGCG and Hup

| 2 |

where I0 is the NMR signal intensity of free ligand and I is the signal intensity of bound ligand during the NMR titration experiments (i.e. the concentration of Hup is varied as 4, 8, 12, 16, and 20 μM), and θ is an relative increase in complex concentration (also referred to as the degree of binding). The explicit derivation of eq 1 has been illustrated in the Supporting Information (see Appendix III).

Amide CSP Experiments for Mapping the Binding Site of EGCG on Hup

For mapping the interaction of EGCG on the protein surface of Hup, the uniformly 15N labeled sample of Hup (concentration ∼ 200 μM) and the stock solution of EGCG (of concentration 20 mM) both were prepared in saline sodium phosphate buffer of strength 50 mM containing 200 mM NaCl that was prepared as described previously.37 Before starting the NMR experiments, the purity of EGCG was checked and its molecular structure was also confirmed by NMR through comparing the chemical shifts of 1H resonances with previously reported NMR assignments. For this, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on EGCG (∼20 mM concentration, solution sample prepared in 100% D2O solvent; more details are given in Supporting Information, Appendix II, Table S2) and the chemical shifts, coupling constant, and overall spectral patterns were compared with those reported previously.89 Indeed, the 1H and 13C NMR spectral pattern were found similar and matched with the previously reported 1H and 13C assignments of EGCG (for the sample dissolved in the acetone-d6 solvent, see Supporting Information, Figure S14).89 Overall, the occurrence of the single set of peaks pertaining to 1H/13C resonances of EGCG without any other prominent signals clearly suggested that the compound is deemed purified for experimental testing. To achieve adequate sensitivity with low (∼200 μM) protein concentration, the 15N SOFAST-HMQC NMR experiment90 was recorded and processed following the parameters described previously.4 For amide CSPs, the SOFAST-HMQC spectra on 15N Hup were recorded with an increasing concentration of EGCG in the (protein–ligand) ratio of 1:0.5, 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, and 1:6. The recorded HMQC spectra were processed using Bruker software TopSpin (v4.0.6) and analyzed using software program CARA (employing MonoScope analysis module). The backbone amide assignment as reported previously37 was transferred to 15N SOFAST-HMQC spectra of Hup and, accordingly, the amide CSPs were estimated as CSP = [(δHfree – δHbound)2+ ((δNfree – δNbound)/5)2]1/2, where δH and δN are the chemical shift of the backbone amide proton and nitrogen, respectively.

NMR Relaxation Measurements

The transverse relaxation rates (R2 = 1/T2) serve as a valuable tool to interrogate molecular interactions. The T2 data was collected using the standard Bruker pulse program library sequence CPMGESGP2D. This is a pseudo-2D NMR experiment (a series of 1D 1H NMR spectra are recorded in an interleaved manner) and involves the CPMG block: 90–[τ–180−τ–τ–180−τ−]n– where 2τ is the spin-echo time between two 180° (inversion) pulses of length 25 μs and n is the loop counter used to vary the CPMG-based T2 time. For decay of transverse magnetization, the CPMG time was varied as 3.3, 6.6, 13.2, 19.8, 26.4, 52.8, 79.2, 105.6, 118.8, 132.0, and 158.4 ms, and for this, we used spin-echo time (2τ) equal to 800 μs, 180° RF hard pulse of 25 μs, and n was varied as 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 32, 48, 64, 72, 80, and 96. The T2 data sets were acquired on both free and bound states of the ligand. Each dataset was averaged over 512 transients using recycle delay equal to 6.0 s, whereas other acquisition parameters used were similar to those used for ZGESGP experiment. The acquired FID signals in the 2D array format were then processed using Bruker command ≪xf2≫ (other processing parameters were identical to those used for processing ZGESGP spectra). The resultant spectra were processed and analyzed in software TopSpin v3.6 using its T1/T2 analysis application tool. The resultant peak intensity profiles were plotted as a function of T2 time and then fitted to a two-parameter exponential decay equation given below

| 3 |

where I(t) is the NMR peak intensity at CPMG-based T2 time equal to t and I0 is the reference signal intensity at t = 0.

FQ Experiment

To further validate the Hup–EGCG binding constant and estimating possible binding sites, we further used the FQ method. The microenvironment surrounding tyrosine moiety of proteins was probed by acquiring the fluorescence emission spectra (from with 285 to 400 nm range) at an excitation wavelength of 280 nm using the Fluorolog (HORIBA JOBIN YVON) fluorescence spectrophotometer. During fluorescence experiments (performed using a 10 mm quartz cuvette at 298 K), the Hup protein was kept constant at a concentration of 40 μM and was titrated with EGCG by progressively increasing its concentration from 5 to 100 μM (to achieve final protein–ligand ratio ∼ 1.0:2.5). For each titration step, the spectra were recorded thrice and corrected for background fluorescence using buffer. Cumulative FQ as per the concentration of added EGCG (titrand) was plotted as a function of emission wavelength. Further to account for the dissociation constant (kD), the Stern–Volmer equation was used as per the details described previously.44

Chemical Reagents for Buffer and NMR Solvents

For experimental testing, EGCG (purity > 95%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO 63103, USA with Product Code-PHR1333, Supelco as Pharmaceutical secondary standards). The deuterium oxide (D2O, 99.9%) used for preparing the NMR samples was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc (Tewksbury, MA, USA). Analytical grade disodium hydrogen phosphate (Na2HPO4), monosodium phosphate (NaH2PO4), and other buffer reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MI, USA).

Acknowledgments

D.K. acknowledges the Department of Science and Technology, India, for financial assistance under SERB EMR Scheme (ref. no. EMR/2016/001756). We would also like to acknowledge the Department of Medical Education, Govt. of Uttar Pradesh, for supporting the High Field (800 MHz) NMR Facility at the Centre of Biomedical Research, Lucknow, and the support of the Fluorescence Spectroscopy facility at IIT Roorkee, India. R.R. acknowledges the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), New Delhi, India, for his fellowship under CSIR-JRF scheme. N.A. acknowledges the Department of Science and Technology, India, for his research fellowship under the DST-INSPIRE PhD Program.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- NMR

nuclear magnetic resonance

- NAP

nucleoid associated protein

- AHP

anti-Helicobacter pylori

- Hup

histone like DNA binding protein of Helicobacter pylori

- ESM

electronic supplementary material

- SBDD