Highlights

-

•

We report a case of 75-year-old Caucasian men with unknown voluminous gastric GIST, who came to our attention complaining melena. We decided to perform a laparoscopic-endoscopic combined surgical approach.

-

•

Intraoperative endoscopy identified gastric GIST and confirmed the submucosal origin and the integrity of the capsule. A 10 cm laparoscopic gastrotomy was carried out along the gastric found in order to realize a laparo-endoscopic rendez-vous technique.

-

•

Laparoscopy has rapidly become a preferable approach for gastric GISTs surgical treatment. The magnified view and the lesser invasiveness of laparoscopic technique allow the surgeon to perform a more meticulous dissection, preventing unexpected bleeding and causing less muscular trauma and less bowel manipulation. All these favourable short-term outcomes associated with laparoscopy do not compromise oncologic results.

Keywords: GIST, Laparoscopic surgery, Endoscopy, Wedge gastric resection, Laparo-endoscopic surgery

Abstract

Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) are the most common malignant subepithelial lesions of gastrointestinal tract, originating from Cajal’s cells and characterized by the over expression of tyrosine kinase receptor C-KIT. The prognosis of this disease is associated with tumour size and mitotic index. Standard treatment of a GIST with no metastasis is surgical resection.

Presentation of case

We report a case of a 75-year-old Caucasian man with unknown voluminous gastric GIST, who came to our attention complaining black stool. We decided to perform a laparoscopic-endoscopic combined surgical approach. Intraoperative gastroscopy identified the gastric GIST and confirmed the submucosal origin and the integrity of the tumor capsule. A 10 cm laparoscopic gastrotomy was carried out along the gastric fundus in order to realize a laparo-endoscopic rendez-vous procedure.

Discussion

Laparoscopic approach is feasible and safe for Gastric GIST both in elective and urgent settings. Even for lesions greater than 5 cm, laparoscopy shows a recurrence rate similar to open surgery when radical resection are performed. An important point to take in consideration is surgical team experience, which seems to be one of the most important factors reducing the incidence of operative complications with better long-term outcomes, both postoperative and oncological.

Conclusion

Mini-invasive approaches for gastric GIST are safe and feasible. The combined approach both laparoscopic and endoscopic has shown to be an effective technique and it may allow a better exposure of the tumour which ensure a radical resection.

1. Introduction

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) are the most common malignant subepithelial lesions of gastrointestinal tract [1], originating from Cajal’s cells and characterized by the over expression of tyrosine kinase receptor C-KIT. The prognosis of this disease is related to tumour size and mitotic index [2]. Standard treatment of a GIST with no metastasis is surgical resection. There are different surgical techniques for management of gastric GISTs, such as open traditional surgery, endoscopic resection, laparoscopy and combined techniques with laparoscopic-endoscopic approach. This article has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [3,4].

2. Case presentation

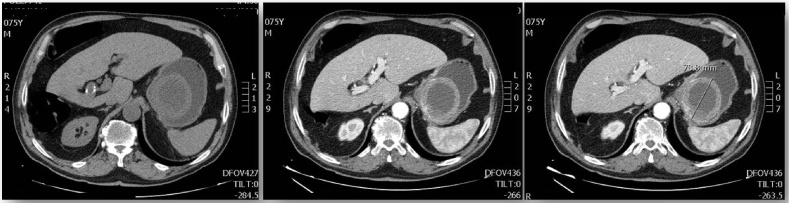

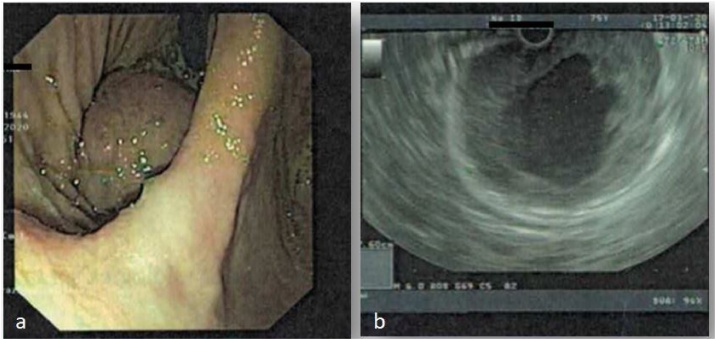

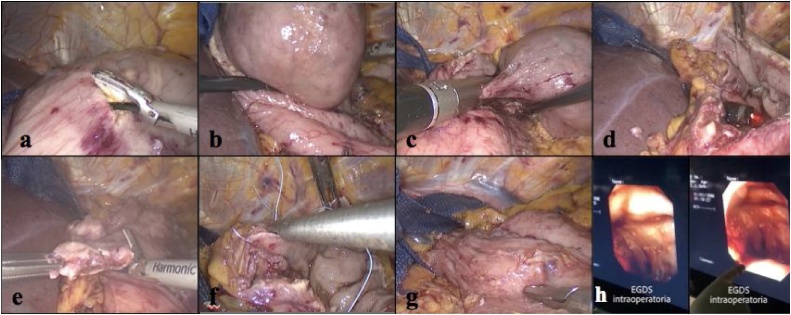

We report a case of a 75-year-old Caucasian man who was admitted to the Emergency Room of our University Hospital complaining remarkable weakness followed by the detection of dark stool highly suggestive for melena in the past few days. He suffered from Hypertension, Prostatic Hyperplasia and Atheromatosis and he was a smoker of 15 cigarettes per day. His family history was negative for other diseases. At the time of admission blood pressure was 100/70 mmHg, with a pulse rate of 99/min and a Glasgow Coma Scale of 15. He was then sent to our observation at General and Emergency Surgery Unit. On physical examination his abdomen was mostly soft and flat, with mild tenderness at pressure in epigastric region. Digital rectal examination demonstrated dark black and tarry stool, suggestive for melena. WBC count was 6.09 × 103/μL with 65.3% of neutrophils, Hb was 7.2 g/dL and haematocrit 20.4%. The esophagogastroduodenoscopy in urgent setting showed a moderate amount of blood in gastric cavity. Near cardial region we found a voluminous submucosal mass of 9 cm of diameter with a large pedicle and surrounded by blood clot. A sclerotherapy injection was carried out in order to stop the bleeding [5]. Contrast-enhanced CT abdominal scan described this voluminous gastric formation with a diameter of 6.5 cm × 7 cm × 7.9 cm, internal fluid components probably due to necrosis and thick contrast-enhanced walls (1 cm max) [Fig. 1]. No metastasis were identified. The lesion was compatible with radiological diagnosis of gastric GIST. Endoscopic ultrasound confirmed the presence of the voluminous mass located in cardial region and extended to gastric fundus [Fig. 2]. The lesion was entirely developed in the submucosal layer and presented a dishomogeneous structure with a central anechoic area due to necrosis [Fig. 2]. No pathological lymph nodes were identified. On the basis of a preoperative diagnosis of gastric GIST with no distant metastasis we decided to perform a laparoscopic wedge resection of the stomach. The procedure was carried out by a senior resident surgeon with an equipe experienced in laparoscopic and oncological surgery. After administration of general anaesthesia the patient was placed in supine decubitus with leg apart which is the standard surgical position we currently use for upper GI surgery (classic French position). We induced pneumoperitoneum with Veress needle [6] and then 4 trocars were placed: one 10-mm trocar in supraumbilical region, two other trocars in right (5 mm) and left (12 mm) hypocondrium and the last one below xiphoid appendix (5 mm). The exploration of the abdominal cavity showed neither peritoneal fluid nor macroscopic metastatic lesions. We detected other two centimetric exophytic lesions arising from the anterior wall of the stomach. In gastric fundus near cardial region, on the greater curvature, it was possible to identify the main lesion with laparoscopic palpation. Greater curvature and gastric fundus were then fully mobilized after section of gastro-splenic ligament and the first three short gastric blood vessels. In consideration of the position and size of the lesion, which was proximal to cardial region, it was not safe to perform a totally laparoscopic wedge resection. Our aim was to guarantee a radical excision of the lesion and at the same time to realize a gastric tissue-sparing resection in order to avoid a gastric stenosis. We decided to perform a laparoscopic-endoscopic combined surgical approach. Intraoperative gastroscopy identified gastric GIST. The pedicle of the mass was in the anterior wall of gastric fundus and the cardias appeared to be free of macroscopic disease, allowing a safe wedge resection with no compromising the esophago-gastric junction. A 10 cm laparoscopic gastrotomy was carried out along the gastric fundus in order to realize a laparo-endoscopic rendez-vous technique (Fig. 3). After gastrotomy the tumour and pedicle was exposed and we achieved a wedge resection with Echelon Flex® (45 mm, blue charge). Then we removed the other two exophytic lesions. We closed the gastrotomy with a double line continuous suture using V-loc® 3-0 (Medtronic). An endoscopic intraoperative second-look demonstrated the radicality of resection and the absence of leakage and/or bleeding from the suture line. The surgical specimens in extraction bag were taken out of the abdomen via supraumblilical port and then all the layers of abdominal wall were closed. The patient was satisfied with the treatment received for the rapid postoperative recovery and advantages of combined endo-laparoscopic procedure. Postoperative course was free of any complications and the patient was discharged on POD 9 with indication to semi solid diet for two weeks. Histopathological results confirmed the preoperative diagnosis of GIST. More precisely, it was a low grade GIST according to Miettenen and Lasota classification [2] with diameter between 5 cm and 10 cm and mitotic count inferior to 5 × 50 HPF (high power fields). The two exophytic lesions that have been removed as well, were a very low grade GIST according to Miettenen and Lasota classification [2] with diameter inferior to 2 cm and mitotic count inferior to 5 × 50 HPF. The resection of all three lesions was complete with a microscopic negative margin (R0).

Fig. 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT abdominal scan showed the voluminous gastric formation with a diameter of 6.5 cm × 7 cm × 7.9 cm, internal fluid components probably due to necrosis and thick contrast-enhanced walls (1 cm max).

Fig. 2.

a) Endoscopic detection of the lesion; b) endoscopic ultrasound shows the central anechoic dishomogeneous area of the tumour, caused by necrosis of the tissue.

Fig. 3.

a) Laparoscopic gastrotomy; b) extroflection of the tumour mass and exposition of the pedicle; c) wedge resection of the lesion; d) flexible endoscope arising after resection of tumour mass; e) excision of exophyric lesions; f) closure of the gastric breach; g) resultant suture grip; h) final intraoperative gastroscopy check.

3. Discussion

Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs) are the most common malignant subepithelial lesions of the gastrointestinal tract. The term GIST was first introduced in 1983 by Mazur and Clark [7]. Gastrointestinal stromal tumours account for 0.1–3% of all neoplasms of digestive tract [1,8]. These tumours are more frequent in the sixth decade of life [1] with rate of occurrence between 6.8–14.5 cases per million individuals per year [9]. GISTs most commonly occur to the stomach (51%), followed by small intestine (36%), colon (7%), rectum (5%), oesophagus (1%) [1] and appendix [10]. GIST may also envolve extragastrointestinal organs, such as omentum, mesentery or retroperitoneum [8], and more rarely pancreas, diaphragm, ovaries, uterus, external male genitalia [11] and urinary bladder [12]. These mesenchymal tumors take origin from the stem cells precursor of interstitial cells of Cajal, which may be considered the pacemaker cells of gastrointestinal movement. The neoplasm is due to oncogenic mutations with over expression of tyrosine kinase receptor KIT and platelet derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFR-α) [9]. Not all GISTs are characterized by the over expression of KIT or PDGFR-α, and these ones are known as wild-type GIST, which present a resistance to tyrosine-kinase-inhibitors like Imatinib and their therapeutic management is very challenging especially when are at metastatic or locallly advanced state [13]. GIST can be also associated with other syndromes like Carney-Stratakis Syndrome and neurofibromatosis type 1 (Von Recklinghausen disease) [11]. For its own characteristics, the GIST is considered to be a malignant tumour because of the tumour spreading, tissues invasion and metastasis. GISTs are classified according to their clinical risk of malignancy in very low, low, intermediate and high grade [14]. Metastatic risk increases with the tumour size, which is a modest predictor of malignant biological behaviour [2]. The risk of recurrence is predicted by Fletcher criteria, related to two clinical pathological factors such as primary tumour size and mitotic count rate [15,16]. GISTs may present several clinical manifestations. The most common symptoms are gastrointestinal bleeding including acute melena, hematochezia and hematemesis or chronic bleeding and consequent anaemia and weakness. Abdominal gravative pain and discomfort occur in large size tumors. The 15–30% of patients are asymptomatic and GISTs are incidentally found during endoscopic procedures or abdominal surgery for other diseases or during autopsy [8,9]. The most frequent complications of GISTs are acute gastrointestinal bleeding, intestinal obstruction due to the mass effect of the tumour, intraperitoneal haemorrhage and peritonitis because of tumor rupture. Endoscopy, endoscopic ultrasonography and CT scan are useful for differential diagnosis of subepithelial lesions, but unable to provide a conclusive diagnosis. Differential diagnosis includes lipoma, neuroendocrine tumour, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, neural stromal tumours such as schwannoma, neuroma and neurofibroma, ectopic pancreas, ab extrinseco compression [1] but also epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, fibromatosis, metastatic melanoma, lymphoma, benign neoplasm of small intestine, dermatofibroma, gastric cancer, solitary fibrous tumour, inflammation bowel disease, diverticulosis, gastritis, peptic ulcer disease [8]. On endoscopy GISTs are usually characterized by ulceration when it increases in size and bleeding is associated. Endo-ultrasonography is useful for differential diagnosis because it gives information about the gastrointestinal wall-layer origin, the characteristics of lesion such as fluid levels, solid tumour, blood vessel distribution and the size of lesion. GISTs are usually detected as hypoechoic solid lesions arising from muscle layer (mostly from muscularis propria layer) [1]. CT scan is the most widely used imaging tool for detecting GIST because allows us an accurate evaluation of tumour size and anatomical relationship with adjacent organs, but the definitive diagnosis of GIST is obtained with histological analysis [15]. Tumour sample for histopathological examination can be achieved via biopsy or with surgical resection. Generally a standard endoscopic forceps biopsy does not provide specimen suitable for a conclusive diagnosis and for assessing malignant potential, because GIST are usually covered by a normal mucosa [1,9]. For masses that appear easily resectable it may not be necessary to obtain a preoperative tissue biopsy and the surgical specimen is used to confirm the diagnosis of GIST. This is preferable when possible, because of the potential risk of biopsy to cause tumour dissemination or bleeding. Instead, endoscopic biopsy is recommended for those patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease candidates to neoadjuvant therapy with tyrosine kinase inhibitors [17]. Immunohistochemical analysis involves the evaluation of KIT, CD34 and DOG1, and it is essential for definitive diagnosis. Treatment of GISTs should be coordinate by a multidisciplinary approach. Oncologist, radiologist and surgeon should collaborate to determine the treatment strategy: primary surgery with curative intent, surgery after neoadjuvant therapy, adjuvant therapy after surgery or palliative treatment [18]. GISTs are poorly responsive to radiotherapy and conventional chemotherapy. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors are gold standard treatment and primary option for metastatic disease, neoadjuvant treatment for unresectable or borderline tumours and adjuvant treatment in patients with high-risk of postoperative recurrence. Surgical resection is the primary choice of treatment for GIST with no distant metastatis [19]. Complete resection with microscopic negative margins (R0) and integrity of pseudocapsule is the main objective of surgery. Sometimes the achievement of disease-free resection margins requires major functional results, and in those cases it may be decided to perform a lesser aggressive surgical resection without obtaining negative margins in low-risk lesions [20]. Lymph nodes dissection is not recommended except when metastasis are clinically suspected. Distant metastasis of GIST are frequently due to haematogenous spreading to the liver or peritoneal seeding, while lymph nodes metastasis are extremely rare. Postoperative follow up is focused on early detection and management of recurrence of GISTs. Among major risks involved in GIST resection there are pseudocapsule perforation and acute bleeding. This is due to biological characteristics of GISTs, which include a rich blood supply. A rupture of pseducapsule may lead to intraabdominal haemorrhage and tumour cells dissemination and is one of the most important risk factors predictive of recurrence after resection [21]. Other risk of recurrence are incomplete resection, inadequate assessment of the peritoneal cavity and a less extensive staging, with undetected intraabdominal tumour spread [22]. The laparoscopic treatment for gastric GISTs was first reported by Kimata in 2000 [23]. Since then, laparoscopy has rapidly become the preferable approach for gastric GISTs surgical treatment [24,25]. The magnified view and the lesser invasiveness of laparoscopic technique allow the surgeon to perform a more meticulous dissection, preventing unexpected bleeding and reducing muscular trauma and bowel manipulation [24]. Other advantages of laparoscopic technique when compared to open surgery are the decreased risk of postperative complication, pain and morbidity, shorter hospital stay [12] and earlier food intake. All these favourable short-term outcomes associated with laparoscopy do not compromise oncological results [26,27]. These evidences make laparoscopic approach a feasible and safe procedure for gastric GIST both in elective and urgent settings [28]. Even for lesions greater than 5 cm, laparoscopy shows a recurrence rate similar to open surgery when radical resection are performed [[29], [30], [31], [32], [33]]. An important point to take in consideration is surgical team experience, which seems to be one of the most important factors reducing the rate of intraoperative complications and unfavourable long-term outcomes, both postoperative and oncological [10,34]. Laparoscopic procedures for gastric GISTs includes wedge resection, transgastric and intragastric surgery [35]. Wedge or atypical segmental resection with preservation of stomach is recommended when possible, and it has to be tailored considering tumour location and size [33]. Laparoscopic organ-preserving gastric resection improves the quality of life in patients with GIST [36]. Another approach for GIST resection is laparoscopic-endoscopic combined surgery, which has recently shown good clinical outcomes [9,28,37]. The contemporary use of laparoscopy and digestive endoscopy facilitates the accurate identification of the submucosal tumour [33]. The laparoscopic-endoscopic rendez-vous technique may allow a better exposure of the submucosal layer and more accurate surgical dissection [38]. Other minimally invasive techniques include robotic surgery with a more accurate hand-sewn reconstruction [39].

4. Conclusion

The treatment of GISTs, and specifically gastric ones, provides a multidisciplinary approach and involves radiologist, oncologist and surgeon. For what concern the surgical management, mini-invasive surgical techniques have shown to be safe and feasible. Among them, the combined laparoscopic-endoscopic surgery has recently provided good outcomes, allowing a better exposure of the tumour and a consequent more precise radical resection. In our experience, we found particularly useful the use of laparo-endoscopic surgery for the management of a large gastric GIST located near cardial region. The use of laparoscopy brought all the advantages of mini-invasive surgical technique and the use of digestive endoscopy added accuracy regarding the tumor resection and the safety in terms of bleeding and suture control.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors report no declarations of interest.

Sources of funding

Di Buono Giuseppe and other co-authors have no study sponsor.

Ethical approval

Ethical Approval was not necessary for this study.

We obtained written patient consent to publication.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Author contribution

Di Buono Giuseppe: study design, data collections, data analysis and writing.

Maienza Elisa: study design, data collections, data analysis and writing.

Buscemi Salvatore: data collections.

Bonventre Giulia: data collections.

Romano Giorgio: study design, data collections, data analysis and writing.

Agrusa Antonino: study design, data collections, data analysis and writing.

Registration of research studies

Not applicable.

Guarantor

Di Buono Giuseppe.

Agrusa Antonino.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Acknowledgements

This article is part of a supplement entitled Case reports from Italian young surgeons, published with support from the Department of Surgical, Oncological and Oral Sciences – University of Palermo.

Contributor Information

Giuseppe Di Buono, Email: giuseppe.dibuono@unipa.it.

Elisa Maienza, Email: elisa.maienza@yahoo.it.

Salvatore Buscemi, Email: buscemi.salvatore@gmail.com.

Giulia Bonventre, Email: giulia.bonv@gmail.com.

Giorgio Romano, Email: giorgio.romano@unipa.it.

Antonino Agrusa, Email: Antonino.agrusa@unipa.it.

References

- 1.Rajravelu R.K., Ginsberg G.G. Management of gastric GI stromal tumors: getting the GIST of it. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2020;91(4):823–825. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2019.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miettinen M., Sobin L.H., Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors of the stomach: a clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, and molecular genetic study of 1765 cases with long-term follow-up. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2005;29:52–68. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000146010.92933.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agha R.A., Borrelli M.R., Farwana R., Koshy K., Fowler A., Orgill D.P., For the SCARE Group The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2018;60:132–136. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Romano G., Agrusa A., Amato G., De Vita G., Frazzetta G., Chianetta D., Sorce V., Di Buono G., Gulotta G. Endoscopic sclerotherapy for hemostasis of acute esophageal variceal bleeding. G. Chir. 2014;35(Mar.–Apr. (3-4)):61–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agrusa A., Romano G., Dominguez L.J., Amato G., Citarrella R., Vernuccio L., Di Buono G., Sorce V., Gulotta L., Galia M., Mansueto P., Gulotta G. Adrenal cavernous hemangioma: which correct decision making process? Acta Med. Mediterr. 2016;32:385–389. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazur M.T., Clark H.B. Gastric stromal tumors. Reappraisal of histogenesis. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1983;7:507–519. doi: 10.1097/00000478-198309000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burch J. StatPearls; 2020. Cancer, Gastrointestinal Stromal (GIST) pp. 1–9. Feb 2020, NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554541/?report=printable Bookshelf ID: NBK554541 PMID: 32119428. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akahoshi K., Oya M., Koga T., Shiratsuchi Y. Current clinical management of gastrointestinal stromal tumor. World J. Gastroenterol. 2018;24(July (26)):2806–2817. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i26.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ayad A.M., Sardar H.A. Enormous gastrointestinal stromal tumor arising from the stomach causing weight loss and anemia in an elderly female: case report. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2019;64:102–104. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2019.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schöffel N., Groneberg D.A., Kaul T., Laatsch D., Thielemann H. 2016. Diagnose und Therapie von Sarkomen im Magen-Darm-Trakt. MMW Fortschritte der Medizin; pp. 60–63. March, MMW-Fortbildungsinitiative: Gastroenterologie für den Hausarzt Regelmäßiger Sonderteil der MMW-Fortschritte der Medizin. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stanek M., Pisarska M., Budzyńska D., Rzepa A., Pędziwiatr M., Major P., Budzyński A. Gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: clinical features and short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic resection. Videosurgery Miniinv. 2019;14(2):176–181. doi: 10.5114/wiitm.2019.83868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Djerouni M., Dumont S.N. Les tumeurs stromales gastro-intestinales sauvages. Bull. Cancer Elsevier. 2020;(February):1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.bulcan.2019.12.007. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0007455120300345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joensuu H. Risk stratification of patients diagnosed with gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Hum. Pathol. 2008;39:1411–1419. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2008.06.025]. [PMID: 18774375] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fletcher C.D., Berman J.J., Corless C., Gorstein F., Lasota J., Longley B.J. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a consensus approach. Hum. Pathol. 2002;33(5):459–465. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.123545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones R.L. Practical aspects of risk assessment in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. J. Gastrointest. Cancer Stromal Tumors. 2014;45:262–267. doi: 10.1007/s12029-014-9615-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Çaynak M., Özcan B. Laparoscopic transgastric resection of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor and concomitant sleeve gastrectomy: a case report. Obes. Surg. 2020;30:1596–1599. doi: 10.1007/s11695-020-04472-w. # Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Simone B., Ansaloni L., Sartelli M., Coccolini F., Di Saverio S., Pantaleo M.A., Saponara M., Nannini M., Abongwa H.K., Napoli J.A., Catena F. What is changing in the surgical treatment of gastrointestinal stromal tumors after multidisciplinary approach? A comprehensive literature’s review. Minerva Chir. 2017;72(June (3)):219–236. doi: 10.23736/S0026-4733.17.07302-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Landi B., Blay J.Y., Bonvalot S., Brasseur M., Coindre J.M., Emile J.F., Hautefeuille V., Honore C., Lartigau E., Mantion G., Pracht M., Le Cesne A., Ducreux M., Bouche O., on behalf of the «Thésaurus National de Cancérologie Digestive (TNCD)» Fédération Francophone de Cancérologie Digestive (FFCD), Fédération Nationale de Centres de Lutte Contre les Cancers (UNICANCER), Groupe Coopérateur Multidisciplinaire en Oncologie (GERCOR), Société Française de Chirurgie Digestive (SFCD), Société Française de Radiothérapie Oncologique (SFRO), Société Française d’Endoscopie Digestive (SFED), Société Nationale Française de Gastroentérologie (SNFGE) Gastrointestinal stromal tumours (GISTs): French Intergroup Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatments and follow-up (SNFGE, FFCD, GERCOR, UNICANCER, SFCD, SFED, SFRO) Dig. Liver Dis. 2019;51:1223–1231. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2019.07.006. Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pantuso G. Surgical treatment of primary gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs): management and prognostic role of R1 resections. Am. J. Surg. 2019:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang C., Gao Z., Shen K., Cao J., Shen Z., Jiang K., Wang S., Ye Y. Safety and efficiency of endoscopic resection versus laparoscopic resection in gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumours: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Surg. Oncol. Elsevier. 2020;46:667–674. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2019.10.030. 0748-7983/© 2019 Elsevier Ltd, BASO. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hohenberger P., Bonvalot, van Coevorden F., Rutkowski P., Stoeckle E., Olungu C., Litiere S., Wardelmann E., Gronchi A., Casali P. Quality of surgery and surgical reporting for patients with primary gastrointestinal stromal tumours participating in the EORTC STBSG 62024 adjuvant imatinib study. Eur. J. Cancer. 2019;120:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.07.028. Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kimata M., Kubota T., Otani Y. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors treated by laparoscopic surgery: report of three cases. Surg. Today. 2000;30(2):177–180. doi: 10.1007/s005950050038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiong Z., Wan W., Zeng X., Liu W., Wang T., Zhang R., Li C., Yang C., Zhang P., Tao K. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: a propensity score matching analysis. J. Gastrointest. Surg. 2019;(July):1–10. doi: 10.1007/s11605-019-04318-6. Springer. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakamatsu K., Lo Menzo E., Szomstein S., Seto Y., Chalikonda S., Rosenthal R.J. Feasibility of laparoscopic resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumor of the stomach. J. Laparoendosc. Adv. Surg. Tech. 2020;28(5) doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Piessen Guillaume. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors: what is the impact on postoperative outcome and oncologic results? Ann. Surg. 2015;262(November (5)):831–840. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001488. PMID: 26583673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inaba C.S., Dosch A., Koh C.Y., Sujatha-Bhaskar S., Pejcinovska M., Smith B.R., Nguyen N.T. Laparoscopic versus open resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: survival outcomes from the NCDB. Surg. Endosc. 2019;33:923–932. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chetta N., Picciariello A., Nagliati C., Balani A., Martines G. Surgical treatment of gastric GIST with acute bleeding using laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a report of two cases. Clin. Case Rep. 2019;7:776–781. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.2093. Wiley. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin J., Huang C., Zheng C. Laparoscopic versus open gastric resection for larger than 5cm primary gastric gastrointestinal stro- mal tumors (GIST): a size-matched comparison. Surg. Endosc. 2014;28:2577–2583. doi: 10.1007/s00464-014-3506-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Badica B., Gancel C.H., Thereau J., Joumond A., Bail J.P., Meunier B., Sulpice L. Surgical and oncological long term outcomes of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) resection-retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Surg. 2018;53:257–261. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu G., Wang J., Che X., He S., Wei C., Li X., Pang K., Fan L. Laparoscopic versus open resection of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors larger than 5 cm: a single-center, retrospective study. Surg. Innov. 2017;24:582–589. doi: 10.1177/1553350617731402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.El-Menyar A., Mekkodathil A., Al-Thani H. Diagnosis and management of gastrointestinal stromal tumors: an up-to-date literature review. J. Cancer Res. Ther. 2017;13(October-December (6)):889–900. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.177499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reimondez S., Moser F., Maldonado P.S., Alcaraz A., Rossini A.R., Obeide L.R. vol. 77. Hospital Privado Universitario de Córdoba, Instituto Universitario de Ciencias Biomédicas de Córdoba; Argentina: 2017. pp. 274–278.www.medicinabuenosaires.com (Gastrectomía atípica laparoscópica en el tratamiento de gist gástrico. Resultados a corto y mediano plazo. Medicina (Buenos Aires)). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Costache M.F., Filip B., Scripcariu D.V., Danilã N., Scripcariu D.V. Management of gastric stromal tumour – multicenter observational study. Chirurgia. 2018;113:780–788. doi: 10.21614/chirurgia.113.6.780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lyu Z., Yang Z., Wang J., Hu W., Li Y. Totally laparoscopic transluminal resection for gastrointestinal stromal tumors located at the cardiac region. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2018;25:2218–2219. doi: 10.1245/s10434-018-6482-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ozcan O., Kaplan M., Yalcin H.C. Laparoscopic organ-preserving gastric resection improves the quality of life in stromal tumor patients an observational study with 23 patients. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2019;90:41–51. PMID: 30638185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tamegai Y., Fukunaga Y., Suzuki S., Lim D.N.F., Chino A., Saito S., Konishi T., Akiyoshi T., Ueno M., Hiki N., Muto T. Laparoscopic and endoscopic cooperative surgery (LECS) to overcome the limitations of endoscopic resection for colorectal tumors. Endosc. Int. Open. 2018;06:E1477–E1485. doi: 10.1055/a-0761-9494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vecchio R., Marchese S., Amore F.F., La Corte F., Ferla F., Spataro L., Intagliata E. Laparoscopic-endoscopic rendez-vous resection of iuxta-cardial gastric GIST. G. Chir. 2013;34(May-June (5/6)):145–148. doi: 10.11138/gchir/2013.34.5.145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Maggioni C., Shida A., Mancini R., Ioni L., Pernazza G. Safety profile and oncological outcomes of gastric gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) robotic resection: single center experience. Int. J. Med. Robot. 2019;15:e2031. doi: 10.1002/rcs.2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.