Abstract

Objective

Cluster genes, specifically the class 3 semaphorins (SEMA3) including SEMA3C, have been associated with the development of Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) in Caucasian populations. We aimed to screen for rare and common variants in SEMA3C in Indonesian patients with HSCR.

Methods

In this prospective clinical study, we analyzed SEMA3C gene variants in 55 patients with HSCR through DNA sequencing and bioinformatics analyses.

Results

Two variants in SEMA3C were found: p.Val337Met (rs1527482) and p.Val579 = (rs2272351). The rare variant rs1527482 (A) was significantly overrepresented in our HSCR patients (9.1%) compared with South Asian controls in the 1000 Genomes (4.7%) and Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC; 3.5%) databases. Our analysis using bioinformatics tools predicted this variant to be evolutionarily conserved and damaging to SEMA3C protein function. Although the frequency of the other variant, rs2272351 (G), also differed significantly in Indonesian patients with HSCR (27.3%) from that in South Asian controls in 1000 Genomes (6.2%) and ExAC (4.6%), it is a synonymous variant and not likely to affect protein function.

Conclusions

This is the first comprehensive report of SEMA3C screening in patients of Asian ancestry with HSCR and identifies rs1527482 as a possible disease risk allele in this population.

Keywords: Damaging effect on protein function, deleterious conservation score, founder effect, Hirschsprung disease, Indonesia, semaphorin 3C, pathogenic variant

Introduction

Hirschsprung disease (HSCR: OMIM# 142623) is a congenital anomaly characterized by a lack of ganglion cells in the bowels, which causes a functional obstruction during infancy.1 HSCR can be classified into the following types: short-segment, long-segment, and total colonic aganglionosis.2

HSCR is a complex genetic disorder and at least 17 genes are reported to contribute to its development, with RET (Ret proto-oncogene) and EDNRB (endothelial receptor type B) accounting for most cases of HSCR.1,2 A cluster of genes called the class 3 semaphorins (SEMA3), including SEMA3C, are also associated with the development of HSCR in Caucasian populations.3–5 It has been postulated that the effect of SEMA3 variant rs11766001 on HSCR could depend on the type of population.6 Additionally, the HSCR phenotype is hypothesized to be determined by a combination of common “low-penetrant” and rare “high-penetrant” variants of identified genes, including RET, GDNF, GFRA1, NTN, PSPN, EDNRB, EDN3, ECE1, SOX10, PHOX2B, ZFHX1B, L1CAM, KBP, NRG1, NRG3, SEMA3A, SEMA3C, and SEMA3D.1,2

Rare variants in SEMA3D were previously associated with the development of HSCR in European ancestries,4 but our recent study failed to identify any rare variants in the SEMA3D gene in Indonesian patients.7 This suggests that (1) the association of such rare variants with HSCR might be limited to specific ethnic groups, or (2) other SEMA3 genes might have a role in the pathogenesis of HSCR.4,8 It is also possible that our sample size had insufficient power to detect such a modest effect.7 Previous studies in populations of Asian ancestry focused only on the role of common SEMA3 variants in the pathogenesis of HSCR.6,9 Therefore, in this study, we aimed to perform a comprehensive screening to identify both rare and common variant(s) in SEMA3C in patients with HSCR in Indonesia.

Material and methods

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada/Dr. Sardjito Hospital (#KE/FK/0110/EC/2020; 23 January 2020). The parents of each patient gave informed consent before the study and sample collection. This work follows the reporting criteria of the STROBE guidelines.

Patients

This prospective clinical research involved 55 (39 male and 16 female) patients with HSCR. The diagnosis of HSCR was established on the basis of clinical findings, contrast enema, and histopathology.10 All HSCR patients in this study were unrelated, of Indonesian descent, and had isolated and sporadic disease. They were previously tested for other HSCR genes, including NRG1 and SEMA3D.7,11 Several reports have noted the role of combined genetic effects of common variants from several genes for the pathogenesis of HSCR, including RET, NRG1, and SEMA3.3,9

Direct Sanger sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood using the QIAamp DNA Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). PCR and direct Sanger sequencing methods were performed following protocols from a previous study10 and used primer sequences for SEMA3C gene analysis as reported in Jiang et al.4

Genotyping of SEMA3C variants rs1527482 and rs2272351

We detected the presence of rs1527482: G>A and rs2272351: G>C variants by direct Sanger sequencing analysis of the SEMA3C gene in Indonesian patients with HSCR. We obtained the minor allele frequencies of rs1527482 (A allele) and rs2272351 (G allele) in individuals of East Asian and South Asian ancestry from the 1000 Genomes Project (https://www.internationalgenome.org/) and the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC; https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/) population databases.12,13

Bioinformatics analysis

We used the SIFT (http://sift.jcvi.org/), PolyPhen-2 (http://genetics.bwh.harvard.edu/pph2/), LRT (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3910100/), Mutation Taster (http://www.mutationtaster.org), Mutation Assessor (http://mutationassessor.org/r3/), FATHMM (http://fathmm.biocompute.org.uk), CADD (http://cadd.gs.washington.edu) algorithm and DANN (https://cbcl.ics.uci.edu/public_data/DANN/) algorithms to predict the potential damaging effect of variants, and GERP (http://mendel.stanford.edu/SidowLab/downloads/gerp/index.html), PhyloP (http://ccg.vital-it.ch/mga/hg19/phylop/phylop.html), SiPhy (http://portals.broadinstitute.org/genome_bio/siphy/index.html) to predict conservation scores, and ClinVar (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar/) to determine clinical significance as described in our previous study.11

Statistical analysis

All statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 21 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Sample size estimation was calculated using a confidence level of 95% and a confidence interval of 14. The calculated minimum size required was 49 samples. The chi-square test was used to establish p-values for the case–control association analysis for SEMA3C rs1527482 and rs2272351 variants. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline characteristic of Indonesian HSCR patients

Most of our HSCR patients were male (71%) with the short-segment aganglionosis type of HSCR (98%). The median age at HSCR diagnosis was 7.9 months (interquartile range, 1.6–38 months), and the most common definitive surgery performed for HSCR patients in our hospital was transanal endorectal pull-through (50%), followed by the Duhamel (23%) and Soave (18.7%) procedures (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with Hirschsprung disease (HSCR) in Indonesia who underwent SEMA3C sequencing analysis.

| Characteristic | n (%) or median (IQR) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 39 (71) |

| Female | 16 (29) |

| Age at HSCR diagnosis (months) | 7.9 (1.6–38) |

| Degree of aganglionosis | |

| Short segment | 54 (98) |

| Long segment | 1 (2) |

| Type of definitive procedure (n = 48) | |

| Transanal endorectal pull-through | 24 (50) |

| Duhamel procedure | 11 (23) |

| Soave procedure | 9 (18.7) |

| Other | 4 (8.3) |

IQR, interquartile range.

Association of SEMA3C variants and HSCR patients

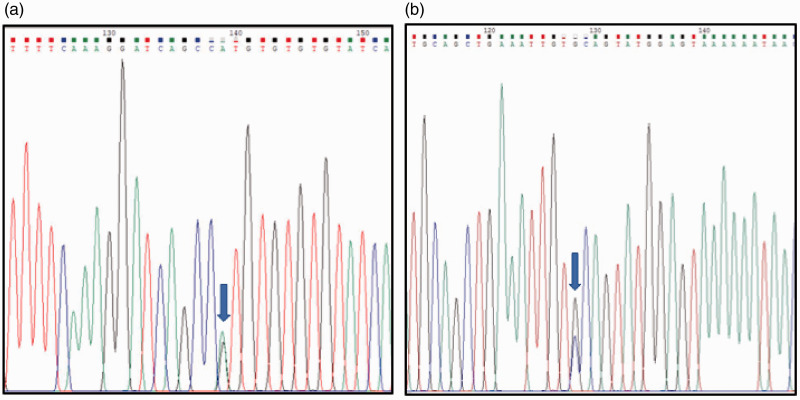

Sanger sequencing detected two variants in the SEMA3C gene in exon 11 (rs1527482) and exon 17 (rs2272351). The rs1527482 variant caused a change of amino acid (p.Val337Met), whereas the rs2272351 variant did not change the amino acid (p.Val579 = ) (Figure 1). The genotype frequencies for rs1527482 and rs2272351 variants in our HSCR patients were GG (45/55), GA (10/55), and AA (0), and GG (4/55), GC (22/55), and CC (29/55), respectively (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Sanger sequencing of (a) exon 11 and (b) 17 of the SEMA3C gene in a patient with Hirschsprung disease; arrow indicates variants rs1527482 (p.Val337Met) (a) and rs2272351 (p.Val579=) (b).

Table 2.

Comparison of SEMA3C variants detected in patients with HSCR in Indonesia and controls in the 1000 Genomes and ExAC databases.12,13

| Variant |

Reference | Frequency of genotype or allele |

Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exon | Nucleotide | Amino acid | Cases | 1000 GenomesA,B | ExACA,B | |||

| 11 | c.1009G>A | p.Val337Met | rs1527482 | Genotype | vs. 1000 Genomes | |||

| GG: 45 | GG: 441, 445 | GG: 3797, 7619 | 2.03 (1.0–4.14)B | 0.048B* | ||||

| GA: 10 | GA: 62, 42 | GA: 492, 543 | 1.48 (0.73–2.96)A | 0.27A | ||||

| AA: 0 | AA: 1, 2 | AA: 17, 14 | vs. ExAC | |||||

| Alleles | 1.54 (0.80–2.96)A | 0.19A | ||||||

| G: 100 | G: 944, 932 | G: 8086, 15,781 | 2.76 (1.44–5.32)B | 0.0024B* | ||||

| A: 10 | A: 64, 46 | A: 526, 571 | ||||||

| 17 | c.1737G>C | p.Val579= | rs2272351 | Genotypes | vs. 1000 Genomes | |||

| GG: 4 | GG: 29, 3 | GG: 253, 23 | 0.81 (0.52–1.26)A | 0.34A | ||||

| GC: 22 | GC: 176, 55 | GC: 1516, 715 | 0.18 (0.11–0.29)B | <0.0001B* | ||||

| CC: 29 | CC: 299, 431 | CC: 2537, 7500 | vs. ExAC | |||||

| Alleles | 0.82 (0.54–1.25)A | 0.35A | ||||||

| G: 30 | G: 234, 61 | G: 2022, 761 | 0.13 (0.08–0.20)B | <0.0001B* | ||||

| C: 80 | C: 774, 917 | C: 6590, 15,715 | ||||||

*p-value of <0.05 was considered significant; A = East Asian ancestry; B = South Asian ancestry; HSCR, Hirschsprung disease.

Next, we compared the risk allele frequencies of rs1527482 (A) and rs2272351 (G) using the 1000 Genomes and ExAC East Asian and South Asian ancestry controls databases. The risk allele frequency at rs1527482 (A) among HSCR patients (9.1%) was significantly different than those reported for South Asian ancestry controls in the 1000 Genomes (vs. 4.7%, odds ratio [OR] = 2.03, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.0–4.14; p = 0.048) and ExAC (vs. 3.5%, OR = 2.76, 95% CI: 1.44–5.32; p = 0.0024) databases, but did not differ from those reported for East Asian ancestry controls in the 1000 Genomes (vs. 6.3%) and ExAC (vs. 6.1%) databases (Table 2).

Although the risk allele frequency of the synonymous variant rs2272351 (G) among HSCR patients (27.3%) also differed significantly from those reported for South Asian ancestry controls in the 1000 Genomes (vs. 6%; p ≤ 0.0001) and ExAC (vs. 4.6%; p ≤ 0.0001) databases, it did not differ from East Asian controls in the same databases (vs. 23.2% and 23.48%, respectively) and it is a synonymous variant (p.Val579=) (Table 2).

Bioinformatics analysis of SEMA3C rs1527482 variant

We used SIFT, PolyPhen-2 (HDiv and HVar), LRT, MutationTaster, MutationAssessor, FATHMM, CADD, and DANN algorithms to predict the potential damaging effect of the SEMA3C rs1527482 variant. Six of the eight algorithms predicted rs1527482 to have a deleterious effect on SEMA3C protein function (Table 3). The thresholds for the deleteriousness of a variant were set as follows: SIFT ≤ 0.05, PolyPhen2 HDIV ≥0.957, PolyPhen2 HVAR ≥ 0.909, LRT = D, MutationTaster = A or D, MutationAssessor >0.65, FATHMM ≤ −1.5, CADD Phred >15, and DANN >0.98.10

Table 3.

Prediction of effects of SEMA3C variant rs1527482 on protein function.

| Variant | SIFT | Polyphen2 – HDiv | Polyphen2 – HVar | LRT | Mutation Taster | Mutation Assessor | FATHMM | CADD Phred | DANN |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1527482 (p.Val337Met) | 0 (deleterious) | 1 (probably damaging) | 0.998 (probably damaging) | D (deleterious) | P (polymorphism) | 3.975 (high) | 1.32 (tolerated) | 33 (deleterious) | 0.999 (protein disrupting) |

SIFT score ≤0.05 = deleterious, SIFT score >0.05 = tolerated; PolyPhen2 HDiv: ≥0.957 = probably damaging, >0.453 and <0.956 = possibly damaging, ≤0.453 = benign; PolyPhen2 HVar: ≥0.909 = probably damaging, >0.447 and <0.909 = possibly damaging, ≤0.446 = benign; LRT: D = deleterious, N = neutral, U = unknown; Mutation Taster: A = disease causing automatic, D = disease causing, N = polymorphism, P = polymorphism_automatic; Mutation Assessor: score >0.65 = deleterious, score ≤0.65 = benign; Mutation Assessor prediction: H, high; M, medium; L, low; N, neutral, where H/M = functional and L/N = non-functional; FATHMM: score ≤ −1.5 = deleterious, score > −1.5 = tolerated; CADD: Phred Score >15 = deleterious, Phred Score ≤15 = tolerated; DANN: score >0.98 = protein disrupting, score >0.93 and <0.98 = splice site/promoter region, score <0.93 = non-protein-disrupting.

All conservation scores predicted the SEMA3C rs1527482 variant to be deleterious. The thresholds used were GERP >2, PhyloP >1.6 and SiPhy >12.1711 (Table 4).

Table 4.

Conservation scores and clinical significance of SEMA3C variant rs1527482.

| Variant | GERP | PhyloP placental | PhyloP vertebrate | SiPhy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rs1527482 (p.Val337Met) | 5.72 (deleterious) | 2.859 (deleterious) | 6.157 (deleterious) | 20.23 (deleterious) |

GERP: score >2 = deleterious, score ≤2 = benign; PhyloP: score >1.6 = deleterious, score ≤1.6 = benign; SiPhy: score >12.17 = deleterious, score ≤12.17 = benign.

Discussion

In this study, we detected two variants, rs1527482 and rs2272351, in the SEMA3C gene in Indonesian patients with HSCR. Previous studies showed the association between two pathogenic variants in SEMA3C and HSCR in people of Caucasian ancestry.4,5 The risk allele for SEMA3C rs1527482 in Indonesian patients with HSCR (9.1%) was significantly overrepresented compared with controls of South Asian ancestry reported in the 1000 Genomes (4.7%) and ExAC (3.5%) databases.12,13

Multiple lines of computational evidence support the deleterious effect of variant rs1527482 (p.Val337Met). Most in silico prediction tools used in the current study (6 of 8) considered this variant to have a damaging effect on SEMA3C protein function (Table 3), and all conservation scores deemed the variant “deleterious” (Table 4). The valine at position 337 in the SEMA3C protein is highly conserved across all mammals, other vertebrates, and the zebrafish.5 We found one report of functional studies on rs1527482 that showed decreased SEMA3C stability caused by the p.Val337Met variant, resulting in a marked reduction in protein secretion.4 This reduction was shown to cause impairment of semaphorin dimerization and binding to its cognate neuropilin and plexin receptors.4 The binding of SEMA3 proteins to the co-receptors neuropilin and plexin is necessary because it activates a holoreceptor complex involved in the development of the enteric nervous system (ENS) by transducing biochemical responses in certain neuronal subtypes.14 Thus, we suggest that the rs1527482 variant plays a role in pathogenesis of HSCR in Indonesia on the basis of the following evidence: (1) its overrepresentation in patients compared with publicly available control populations (ExAC and 1000 Genomes); (2) support for a deleterious effect from multiple lines of computational evidence; (3) conservation scores; and (4) previously published functional analysis in HSCR patients.4

The HSCR phenotype is likely determined by a combination of common and rare variants of identified genes.1,2 Our study provides further evidence for the role of the common variant (rs1527482) in SEMA3C in the HSCR phenotype by providing data from a population genetically different from those of previous studies.1,4 In addition, our previous study investigated only three specific genetic markers within a locus on chromosome 7q21.11 containing the SEMA3A, SEMA3C, and SEMA3D genes—rs1583147, rs12707682, and rs11766001—in Indonesian patients with HSCR.6 However, there are three novel aspects in the current study: (1) this is the first screening for rare and common variants of SEMA3C in a population of Asian ancestry (vs. a Caucasian population4); (2) we show an association between SEMA3C rs1527482 variant and HSCR risk; and (3) we performed the first screening for rare and common variants of SEMA3C (vs. screening only for common variants of SEMA3 in an Asian population).6,9

In contrast, rs2272351 is a synonymous variant that occurs at high frequency in most populations. Interestingly, we found that the frequency of this variant in Indonesian patients with HSCR differed significantly from that of controls of South Asian ancestry, but was similar to that reported in controls of East Asian ancestry.12,13 These findings might imply that the genetic background of our population is closer to that of East Asia than South Asia. Previous reports demonstrated that SEMA3 rs11766001 and F5 Leiden variants were almost absent in Indonesian populations but occur at high frequencies in Caucasian populations.6,15

It should be noted that our study did not account for other factors that might alter the effect of variants on HSCR, such as sex and aganglionosis subtype. In addition, a multicenter study with a larger sample size is necessary to confirm the results from our small, single-center study. Nonetheless, the data implicating the role of SEMA3C rs1527482 provide an impetus for replication of this study in other populations.

Our study used allele frequencies from public databases (1000 Genomes and ExAC) as controls. This approach has some advantages, such as eliminating the need for additional control sequencing for every study.16 However, population stratifications between our case data and reference datasets such as these may introduce biases to the statistical analysis and several challenges, including deficiencies in individual data, ancestry differences, and methodological differences in sequencing analysis.16 These facts should be taken into consideration when interpreting our findings. Indonesian populations are not represented in databases such as 1000 Genomes and ExAC; therefore, additional data on allele frequencies of SEMA3C variants are needed through screening of healthy individuals in our population.

There are challenges in unraveling the genetic mechanisms of HSCR because it is a complex genetic disorder.1 HSCR arises due to the failure of migration, proliferation, and differentiation of ENS progenitors in the intestines. Disease pathogenesis might arise from a combination of rare and common variants of identified genes and alterations in expression of specific genes during ENS development.1,17 A previous study suggested the following approach to detect pathogenic variants associated with HSCR: a combination of next-generation sequencing and genome-wide association studies and selected statistical analysis, followed by in silico analysis, functional studies, and animal models.1

The role of combined common variants from several genes in the pathogenesis of HSCR has been reported.2,3,9,18 Whereas an individual common variant might give a moderate risk for HSCR (OR ∼2), a combination of several variants might result in a higher risk for HSCR (OR up to ∼30). These accumulation risk allele (variant) dosages are named as genetic modifiers of HSCR.2,3,9,18 Therefore, HSCR risk might be affected by widespread and variable genetic susceptibility from many genes, which is implied by the different clinical manifestations and recurrence risks between families.2 Our findings implicating SEMA3C variants increases our current understanding of the genetic architecture underlying the HSCR phenotype in terms of the additive contribution of different alleles. Identification of all risk alleles ultimately will allow precise prediction of HSCR risk, using polygenic risk score analysis, and a better understanding of the molecular pathways in HSCR, which in turn could lead to novel therapeutic interventions.

In conclusion, this is the first comprehensive report of SEMA3C gene screening in HSCR patients of Asian ancestry. We identified variant rs1527482 as a possible disease risk allele in this population.

Acknowledgement

We thank the patients and families who were involved in this study. We are grateful to a native speaker at the English Services Center, Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada, for editing and proofreading our manuscript.

Footnotes

Author contributions: G, NA, KI, and AM conceived the study; G and PSL drafted the manuscript; RS, RTP, NA, KI, and AM critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content; G, RTP, and AM collected samples; G, PSL, FR, M, ASK, PI, DV, SS, WW, and RS analyzed data; RS conducted the bioinformatics analysis; and FR, M, ASK, PI, DV, SS, and WW conducted the experimental PCR-based work for Sanger sequencing. All authors have read and approved the manuscript, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the submission. The raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant from the Ministry of Research and Technology/National Agency for Research and Innovation (#2822/UN1.DITLIT/DIT-LIT/PT/2020 to G, AM, and NA).

ORCID iDs: Gunadi https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4707-6526

Marcellus https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4457-1767

Alvin Santoso Kalim https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3313-9063

William Widitjiarso https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8851-1029

Poh San Lai https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3352-2000

References

- 1.Alves MM, Sribudiani Y, Brouwer RW, et al. Contribution of rare and common variants determine complex diseases-Hirschsprung disease as a model. Dev Biol 2013; 382: 320–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tilghman JM, Ling AY, Turner TN, et al. Molecular genetic anatomy and risk profile of Hirschsprung’s disease. N Engl J Med 2019; 380: 1421–1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kapoor A, Jiang Q, Chatterjee S, et al. Population variation in total genetic risk of Hirschsprung disease from common RET, SEMA3 and NRG1 susceptibility polymorphisms. Hum Mol Genet 2015; 24: 2997–3003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang Q, Arnold S, Heanue T, et al. Functional loss of semaphorin 3C and/or semaphorin 3D and their epistatic interaction with ret are critical to Hirschsprung disease liability. Am J Hum Genet 2015; 96: 581–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang Q, Turner T, Sosa MX, et al. Rapid and efficient human mutation detection using a bench-top next-generation DNA sequencer. Hum Mutat 2012; 33: 281–289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunadi, Makhmudi A, Agustriani N, et al. Effects of SEMA3 polymorphisms in Hirschsprung disease patients. Pediatr Surg Int 2016; 32: 1025–1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunadi, Kalim AS, Budi NYP, et al. Aberrant expressions and variant screening of SEMA3D in Indonesian Hirschsprung patients. Front Pediatr 2020; 8: 60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luzón-Toro B, Fernández RM, Torroglosa A, et al. Mutational spectrum of semaphorin 3A and semaphorin 3D genes in Spanish Hirschsprung patients. PLoS One 2013; 8: e54800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q, Zhang Z, Diao M, et al. Cumulative risk impact of RET, SEMA3, and NRG1 polymorphisms associated with Hirschsprung disease in Han Chinese. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017; 64: 385–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Setiadi JA, Dwihantoro A, Iskandar K, et al. The utility of the hematoxylin and eosin staining in patients with suspected Hirschsprung disease. BMC Surg 2017; 17: 71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunadi, Budi NYP, Sethi R, et al. NRG1 variant effects in patients with Hirschsprung disease. BMC Pediatr 2018; 18: 292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The 1000 Genomes Project Consortium . A map of human genome variation from population-scale sequencing. Nature 2010; 467: 1061–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.The Exome Aggregation Consortium. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature 2016; 536: 285–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tran TS, Kolodkin AL, Bharadwaj R. Semaphorin regulation of cellular morphology. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2007; 23: 263–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Makhmudi A, Sadewa AH, Aryandono T, et al . Effects of MTHFR c.677C>T, F2 c.20210G>A and F5 Leiden polymorphisms in gastroschisis. J Invest Surg 2016; 29: 88–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guo MH, Plummer L, Chan YM, et al. Burden testing of rare variants identified through exome sequencing via publicly available control data. Am J Hum Genet 2018; 103: 522–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaroy EG, Acosta-Jimenez L, Hotta R, et al. “Too much guts and not enough brains”: (epi)genetic mechanisms and future therapies of Hirschsprung disease - a review. Clin Epigenetics 2019; 11: 135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gunadi, Iskandar K, Makhmudi A, et al. Combined genetic effects of RET and NRG1 susceptibility variants on multifactorial Hirschsprung disease in Indonesia. J Surg Res 2019; 233: 96–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]