Abstract

Background

Emerging evidence indicates that metabolism reprogramming and abnormal acetylation modification play an important role in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) progression, although the mechanism is largely unknown.

Methods

Here, we used three public databases (Oncomine, Gene Expression Omnibus [GEO], The Cancer Genome Atlas [TCGA]) to analyze ESCO2 (establishment of cohesion 1 homolog 2) expression in LUAD. The biological function of ESCO2 was studiedusing cell proliferation, colony formation, cell migration, and invasion assays in vitro, and mouse xenograft models in vivo. ESCO2 interacting proteins were searched using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) and mass spectrometry. Pyruvate kinase M1/2 (PKM) mRNA splicing assay was performed using RT-PCR together with restriction digestion. LUAD cell metabolism was studied using glucose uptake assays and lactate production. ESCO2 expression was significantly upregulated in LUAD tissues, and higher ESCO2 expression indicated worse prognosis for patients with LUAD.

Results

We found that ESCO2 promoted LUAD cell proliferation and metastasis metabolic reprogramming in vitro and in vivo. Mechanistically, ESCO2 increased hnRNPA1 (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1) binding to the intronic sequences flanking exon 9 (EI9) of PKM mRNA by inhibiting hnRNPA1 nuclear translocation, eventually inhibiting PKM1 isoform formation and inducing PKM2 isoform formation.

Conclusions

Our findings confirm that ESCO2 is a key factor in promoting LUAD malignant progression and suggest that it is a new target for treating LUAD.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13046-021-01858-1.

Keywords: Acetylation; Metabolism reprogramming; Lung adenocarcinoma; ESCO2, hnRNPA1

Background

Lung cancer is a heterogeneous tumor with high morbidity and mortality, and is a serious threat to human health [1, 2]. Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) is the most common histologic type of lung cancer, accounting for about 50% of all lung cancers. On average, more than 7500 people die from cancer every day [3]. More than 35% of all cancer deaths are from lung cancer [4]. In recent years, many targeted therapies, such as anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) [5], EGFR [6], ROS1 [7], RET [8], HER2 [9], and MEK [10], have become available for advanced lung cancer, and more are in development [11]. Although there are many means of treating lung cancer, no specific drugs have been found so far [12]. Due to tumor heterogeneity, there is an urgent need to identify new therapeutic targets.

Establishment of cohesion 1 homolog 2 (ESCO2) is an evolutionarily conserved cohesion acetyltransferase that exerts essential functions in the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion [13]. In recent years, ESCO2 has been identified as an essential factor in cancer progression in multiple human cancers [14–17]. Compared with conventional chemotherapy, ESCO2 may become a more promising option for renal cell carcinoma treatment intervention [15]. ESCO2 is highly expressed in aggressive melanomas and breast cancer [16, 18]. In gastric cancer, ESCO2 promotes cell proliferation by modulating the p53 and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling pathways [19]. However, its biological function and clinical significance in lung cancer remain unclear.

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1 (hnRNPA1) is an RNA-binding protein that associates with pre-mRNAs in the nucleus and influences pre-mRNA processing, as well as other aspects of mRNA metabolism and transport, and plays a key role in regulating alternative splicing [20, 21]. The pyruvate kinaseisoform PKM2 is widely expressed in cancer for maintaining glycolysis-dominant energy metabolism, while PKM1 promotes oxidative phosphorylation [22]. These two isoforms result from mutually exclusive alternative splicing of PKM pre-mRNA, reflecting the inclusion of either exon 9 (PKM1) or exon 10 (PKM2), required for tumor cell proliferation [23]. Clinical cancer samples support the notion that hnRNPA1 overexpression decreases the PKM1/PKM2 ratio, which has a positive effect on glycolysis-dominant metabolism [24].

In the present research, we found that high ESCO2 expression in LUAD was associated with poor prognosis. Overexpression of ESCO2 promoted LUAD cell proliferation, colony formation, migration, and invasion in vitro, while ESCO2 knockdown inhibited LUAD cell malignant progression in vitro and tumorigenesis and metastasis in vivo. Coimmunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and mass spectrometry (MS) analysis suggested that ESCO2 could interact with hnRNPA1, which is involved in mRNA splicing or processing. Moreover, we found that ESCO2 can acetylate hnRNPA1 at lysine 277 (K277) to retain hnRNPA1 in the nucleus. Only in the nucleus can hnRNPA1 regulate PKM splicing to promote PKM2 generation and inhibit PKM1 generation, leading to LUAD metabolism reprogramming. The present study indicates the functional roles of ESCO2 in LUAD progression and that ESCO2 may be a potential therapeutic target for LUAD.

Materials and methods

Tissue samples and cell culture

Primary cancer tissue and normal lung tissue were collected from patients with lung cancer at the SixthAffiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. The cases were collected based on a clear pathological diagnosis and patient consent, and the study was approved by the Internal Review and Science Committee of the Sixth Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. The human LUAD cell lines A549 and NCI-H1975 were purchased from the Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). HEK293T cells were purchased from ATCC and cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) containing 10% FBS. All cells were maintained at 37 °C and5% CO2 in a humidified incubator.

Public database analysis and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

LUAD gene expression datasets of Garber et al., Hou et al. and Okamaya et al. were analyzed via Oncomine database (https://www.oncomine.org). LUAD gene expression datasets (GSE74706, GSE21933, GSE32863, GSE50081 and 31,210) were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) database. 515 LUAD and 59 normal lung tissue samples were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) dataset (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). The TCGA LUADsamples were subdivided into high and low ESCO2expression groups and analyzed with GSEA 2.0.9 software (http://www.broadinstitute.org/gsea/).

Plasmid constructs, transfection, and stable silencing

Plasmids were constructed by homologous recombination. Briefly, after primer design and synthesis, complementary DNA (cDNA) was amplified using Phanta Max Super-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Vazyme, cat: C505). The PCR products were purified and recovered according to the protocol of a general DNA purification and recovery kit (Tiangen Biochemical Technology, DP214–03). Then, recombination, transformation, coating, cloning identification, and plasmid extraction were performed. The mutants of hnRNP A1-HA were produced usingMut Express II Fast Mutagenesis Kit V2 (vazyme, C214). The A549 and NCI-H1975 cells were transfected with overexpression vector using Lipofectamine 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA). LUAD cell lines with stable ESCO2 silencing were constructed using lentivirus pLV3short hairpin RNA (shRNA) as previously described [4]. The lentivirus pLV3-ESCO2 shRNA was purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). The sequences of the primers and shRNAs used in the study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Immunofluorescence staining

NCI-H1975 cells were transfected with ESCO2-FLAG vectors, and plated on glass coverslips. The cell density was about 50%; the cells were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) twice, fixed with 1 mL 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 20 min, and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 for 7 min. The cells were rinsed twice with precooled PBS and blocked with 2% BSA (bovine serum albumin) at room temperature for 2 h. Primary antibody was added and incubated at 4 °C overnight, following which the samples were incubated with secondary antibodies. The nuclei were stained with DAPI, and examined under a microscope.

Quantitative real-time PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from treated A549 and NCI-H1975 cells using TRIzol total RNA isolation reagent (Invitrogen). Then, cDNA was synthesized from the total RNA using a PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TAKARA). ESCO2 mRNA expression was detected using quantitative PCR (q-PCR) following the manufacturer’s protocol. ESCO2 and GAPDH expression levels were measured using the comparative threshold cycle (2-ΔΔCt) method. The primer sequences used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Western blotting

Proteins were extracted from cells or tissue using lysis buffer (1 mM EDTA, 1% SDS, 5 mM DTT, 10 mM PMSF, 50 mMTris–HCl [pH 8.0], protease inhibitor cocktail). Protein concentrations were determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay. Total cell lysates were fractionated by 8% or 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), transferred to PVDF membranes. The primary antibodies used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Cell growth and colony formation assays

For the cell growth assay, 1 × 104 treated LUAD cells were seeded in 24-well plates, and counted at 24, 48, 72, 96, and 120 h. For the colony formation assays, 5 × 102 treated LUAD cells were seeded in 6-well plates and cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS for 8 or 10 days. The clones were fixed in methanol and stained with crystal violet solution.

Migration and invasion assays

The in vitro migration and invasion assays were performed using Transwell chambers. For the migration assay, 1 × 105 LUAD cells with ESCO2 overexpression or silencing were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium in the upper compartment of a Transwell chamber. For the invasion assay, 2 × 105 LUAD cells with ESCO2 overexpression were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium with 0.1% FBS in Matrigel-coated upper Transwell chambers. For both assays, the bottom chambers were filled with RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS. The chambers were stained with 0.5% crystal violet. Migrated and invaded cells were counted under a microscope.

In vivo xenograft tumor model

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the ThirdAffiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University. For the in vivo tumor growth assay, 5 × 106 control or ESCO2 knockdown NCI-H1975 cells were injected into the left and right flanks of BALB/c null mice (n = 6). After 21 days, all tumors were stripped and weighed. For the in vivo metastasis assay, control or ESCO2 knockdown NCI-H1975 cells were luciferase (Luc)-labeled using the lentivirus system. NCI-H1975-Luc-NC (negative control) or NCI-H1975-Luc ESCO2shRNA cells (2 × 106 cells) were injected into the tail veins of NOD-SCID (nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient) mice. After 45 days, the metastatic foci were detected using the IVIS 200 imaging system (Xenogen, Alameda, CA, USA).

Silver staining and mass spectrometry (MS)

HEK293T cells were transfected with Flag-ESCO2 vector for 48 h using Lipofectamine 2000. Treated HEK293T cells were lysed in Co-IP lysis buffer (P0013, Beyotime, Shanghai, China). Co-IP was performed using anti-FLAG/anti-HAantibodiesand protein A/G agarose beads (sc-2003, Santa Cruz) to extractthe complexes. Gel bands were detected using a silver staining kit (P0017S, Beyotime) combined with MS following the manufacturer’s protocol. According to a previously published method [25], the peptides of the bands were analyzed using nano-LC–MS/MS. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD023527 and PXD23600.

In vitro acetylation assay

FLAG-tagged ESCO2, HA-tagged hnRNPA1, and their mutant proteins were purified from HEK293T cells using a FLAG Immunoprecipitation Kit (FLAGIPT1, Sigma) or Anti-HA Immunoprecipitation Kit (IP0010, Sigma). Recombinant ESCO2 proteins were incubated with recombinant hnRNPA1 or its mutants in 30 μL reaction buffer (50 mMNaCl, 50 mMTris-HCl [pH 8.0], 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 0.1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol) at 37 °C for 30 min.

RNA affinity purification

First, pretreatment streptomycin beads:100 μL streptavidin-agarose beads were rinsed twice using pre-cooled 500 μLbinding buffer (pH 7.5), centrifuged at 4 °C at 2500 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Then, 1 nmol biotin probe–labeled RNA fragments were bound with 100 μL streptavidin-agarose beads at 4 °C overnight. Cellular nuclear protein was prepared using a Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit (Beyotime). Purified protein or nucleoprotein and tRNA were added to the beads, incubated at 30 °C for 10 min, centrifuged at 4 °C at 2500 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant was discarded. Then, the pretreatment protein was added, incubated at 4 °C for 2 h, centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C, rinsed twice with pre-cooled binding buffer, and centrifuged at 2500 rpm for 5 min at 4 °C. Finally, the elucidated mixtures were detected using western blotting. The 5′ biotin-labeled RNAs used in the study are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

RT-PCR and PKM splicing assays

PKM splicing assays were performed according to a previous study [26]. Briefly, total mRNA was extracted from cells or tissue samples using TRIzol. mRNA reverse transcription was performed using the PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (TAKARA). The PCR products were digested using PstI, and the digested mixtures were resolved by 8% non-denaturing PAGE. The primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Measurement of glucose uptake and lactate production

A549 and NCI-H1975 cells at the logarithmic growth stage were inoculated in a 12-well plate at 1 × 105 cells/well. The experiment was divided into the control group (non-transfected cells) and transfection group. After 36 h, the cells were incubated with phenol red–free RPMI 1640 medium for 8 h, and the glucose content in the culture supernatant was detected using Glucose Colorimetric Assay kit (BioVision, K606–100) according to the operating instructions. The glucose content of the non-transfected group was used as the control.

Treated LUAD cells were seeded into 6-well plates. Lactate production was measured using a Lactate Colorimetric Assay Kit II (BioVision, K627–100) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, at 36 h post-transfection, phenol red–free RPMI 1640 medium without FBS was added to a 6-well plate of subconfluent cells and cultured for 4 h. A standard curve of nmol/well versus the OD450nm (optical density at 450 nm) value was plotted according to the measurement of the lactate standard. The OD450nm values of the sample were applied to the standard curve to calculate the lactate concentrations of the test samples (n = 3).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD); data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 5. Survival curves were described using Kaplan–Meier plots and were calculated using the log-rank test. Statistical differences between two groups were analyzed using an independent Student’s t-test (2-tailed). P < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001 were considered statistically significant.

Results

ESCO2 is upregulated andassociated with poor prognosis in LUAD

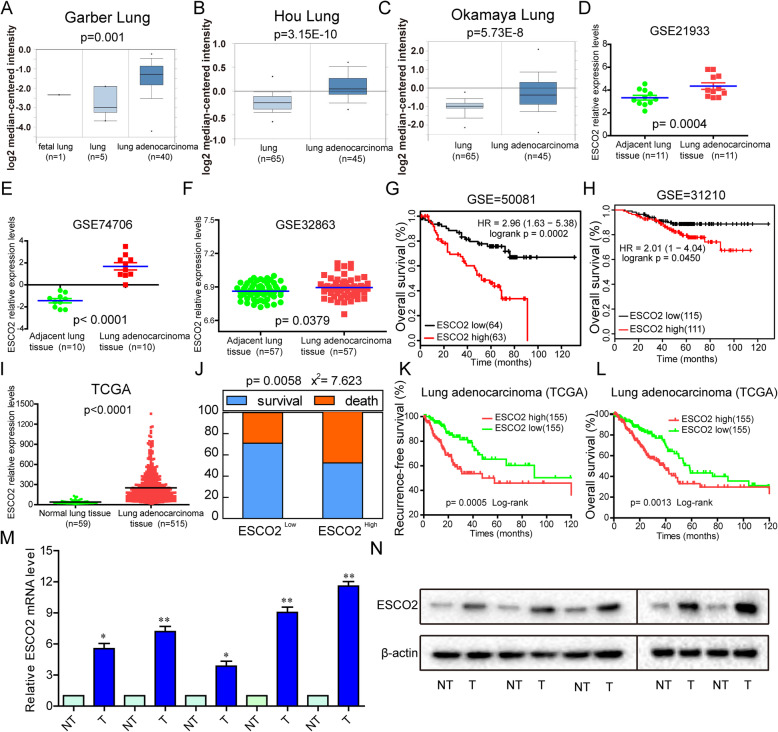

ESCO2 mRNA expression in normal lung tissues and LUAD tissues (Garbar lung, Hou lung, Okamaya lung) was detected using the Oncomine database. We found that ESCO2 expression was significantly higher in LUAD tissues than in normal tissues (p = 0.001, p = 3.15E-10 and p = 5.73E-8; Fig. 1a–c). Three LUAD mRNA expression profiling datasets (GSE21933, GSE10072, GSE32863) were analyzed for the ESCO2 mRNA expression levels between LUAD tissues and their adjacent normal tissues. The analysis showed that ESCO2 expression was significantly upregulated in LUAD tissues compared with the adjacent normal lung tissues (p = 0.0004, p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0379; Fig. 1d–f).

Fig. 1.

Abnormal expression of ESCO2 is associated with poor prognoses in LUAD. a–c ESCO2 mRNA expression in normal lung tissues and LUAD tissues was detected using the Oncomine database. d–f ESCO2 mRNA expression in normal lung tissues and paired LUAD tissues was analyzed based on three LUAD mRNA expression profiling datasets (GSE21933, GSE10072, GSE32863). g and h Patients in the GSE50081 (g) and GSE31210 (h) datasets with high ESCO2 expression had shorter OS. (I) ESCO2 mRNA expression levels were analyzed in normal lung tissues and LUAD tissues from TCGA database. j–l Analysis of TCGA LUAD cohort showed that, compared with patients with low ESCO2 expression levels (the lowest 30%), patients with high ESCO2 mRNA expression (the highest 30%) had higher death rates, shorter disease-free survival, and shorter OS. m and n ESCO2 mRNA (m) and ESCO2 protein (n) expression levels were detected in normal lung tissues and paired LUAD tissues (n = 5)

To elucidate the relevance of ESCO2 overexpression to the survival of patients with LUAD, two publicly accessible microarray datasets of patients with LUAD were analyzed. From the GSE50081 and GSE31210 datasets, patients with high ESCO2 expression had shorter overall survival (OS) (p = 0.0002 and p = 0.0450; Fig. 1g and h). Moreover, The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database showed that ESCO2 gene expression levels in LUAD tissue was significantly higher than that in normal lung tissue (p < 0.0001; Fig. 1i). TCGA LUAD cohort showed that, compared with patients with low ESCO2 expression (the lowest 30%), patients with high ESCO2 mRNA expression (the highest 30%) had higher rates of death, shorter disease-free survival, and shorter OS (p = 0.0058, p = 0.0005 and p = 0.0013; Fig. 1j–l). We performed a chi-square test to clarify the correlation between ESCO2 low and high expression on the clinicopathological features of LUAD. Our findings indicated that high ESCO2 mRNA expression levels werecorrelated significantly positively with pT status (p = 0.001), pN status (p = 0.003), and clinical stage (p = 0.005) (Table 1). To demonstrate ESCO2 expression in LUAD tissues, we performed qPCR and western blotting on five LUAD tissues and the corresponding non-tumor (NT) tissue samples; the results showed that ESCO2 mRNA and protein expression levels werelower in the NT tissues than in the LUAD tissues (Fig. 1m and n). Collectively, our findings indicate that ESCO2 level was significantly upregulated in LUAD and was significantly negatively correlated with OS and DFS, suggesting that ESCO2 may serve as a molecular marker for LUAD treatment and as a promoter of tumorigenesis.

Table 1.

Comparison of clinical features between LUAD patients with low and high ESCO2 levels in TCGA database

| Clinical character# | Clinical groups |

ESCO2 | x2 | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High (n = 155) (%) |

-Low (n = 155) (%) |

||||

| Age (years) | ≤ 60 | 54 (34.8) | 41 (26.5) | 2.611 | 0.106 |

| > 60 | 95 (61.3) | 108 (69.7) | |||

| Gender*** | Male | 91 (58.7) | 59 (38.1) | 13.23 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 64 (41.3) | 96 (61.9) | |||

| ALK Translocation | No | 54 (34.8) | 71 (45.8) | 0.377 | 0.539 |

| Yes | 12 (7.7) | 12 (7.7) | |||

| pT status*** | T1 T2 ~ T4 | 37 (23.9) | 66 (42.6) | 12.27 | < 0.001 |

| 117 (75.5) | 88 (56.8) | ||||

| pN status** | N0 | 88 (56.8) | 110 (71.0) | 8.771 | 0.003 |

| N1 ~ N2 | 66 (42.6) | 40 (25.8) | |||

| pM status* | M0 | 106 (68.4) | 101 (65.2) | 4.026 | 0.045 |

| M1 | 13 (8.4) | 4 (2.6) | |||

| Recurred/Progressed** | No | 62 (40.0) | 88 (56.8) | 8.317 | 0.004 |

| Yes | 67 (43.2) | 46 (29.7) | |||

| Clinical Stage** | Stage I ~ IIA | 83 (53.5) | 106 (68.4) | 7.761 | 0.005 |

| Stage IIB ~ IV | 70 (45.2) | 46 (29.7) | |||

Differences with *p<0.05, **p<0.01 or ***p<0.001 were considered statistically significant

#American Joint Committee on Cancer classification (Version 7) (AJCC)

ESCO2 overexpression promotes the malignant phenotype of LUAD cells

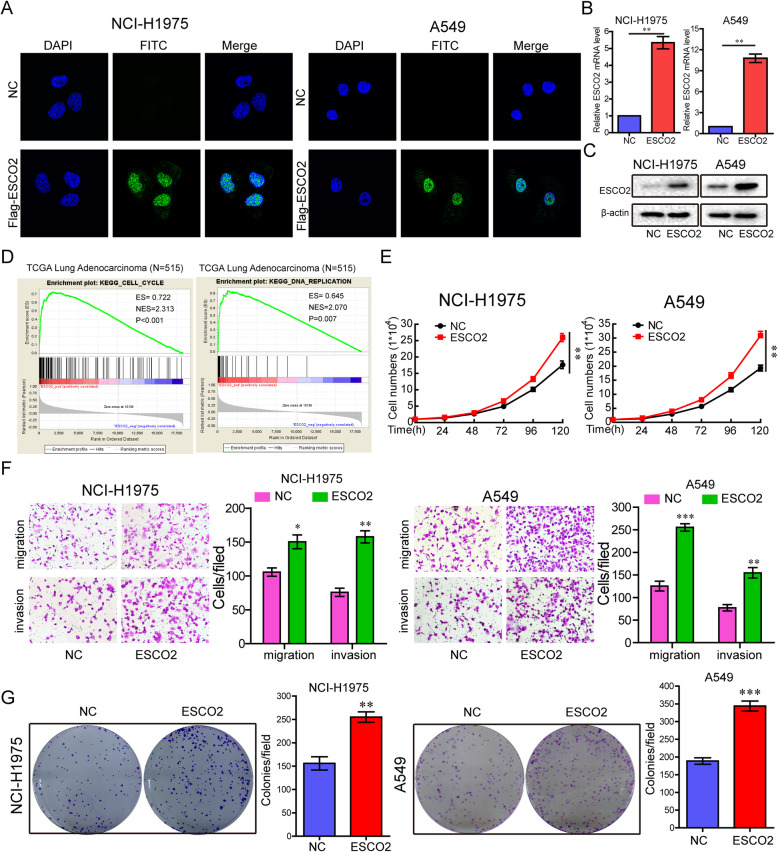

To demonstrate the influence of ESCO2 on cancer growth, metastasis, and colony formation, we generated aESCO2-FLAG construct, where the FLAG tag (six amino acids) was fused to the full-length ESCO2 transcript. The constructs were transfected into NCI-H1975 and A549 cells, and the expression of the construct was examined using immunofluorescence staining, RT-qPCR, and western blotting. The results suggested the successful transfection of ESCO2 into the cells (Fig. 2a–c).

Fig. 2.

Enforced expression of ESCO2 promotes LUAD cell growth, metastasis, and colony formation in vitro. a–c ESCO2-FLAG constructs were transfected into NCI-H1975 and A549 cells; FLAG was immunostained using anti-FLAG antibodies (a); ESCO2 mRNA and protein expression levels were detected by q-PCR (b) and western blotting (c), respectively. d GSEA showed that the cell cycle signatures and DNA replication signatures had a significant positive correlation with the ESCO2 mRNA expression levels in TCGA LUAD cohort. e–g The effects of ESCO2 overexpression on cell growth (e), migration and invasion (f), and colony formation (g) were detected in NCI-H1975 and A549 cells. Data are the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

The global mRNA expression profiles of TCGA LUAD were detected using gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) software. GSEA plots showed that the cell cycle signatures (p < 0.001) and DNA replication signatures (p = 0.007) had a significantly positive correlation with ESCO2 mRNA expression levels in TCGA LUAD cohort (Fig. 2d). To identify the effects of ESCO2 overexpression in the malignant phenotype of LUAD cells, the ESCO2 construct was transiently transfected into NCI-H1975 and A549 cells. ESCO2 overexpression significantly promoted cell growth in both NCI-H1975 and A549 cells (p = 0.0011 and p = 0.0012; Fig. 2e) and significantly increased cell invasion and migration (Fig. 2f). Colony formation was also significantly increased significantly in the ESCO2 overexpression LUAD cells (p = 0.0054 and p = 0.0051; Fig. 2g).

Stable silencing of ESCO2 inhibited the aggressive phenotype of LUAD cells in vitro and in vivo

To prove the influence of ESCO2 on the aggressive phenotypeof LUAD cells in vitro, and on growth and metastasis in vivo, ESCO2 expression was stably silenced using shRNA. ESCO2 mRNA and protein expression levels were detected by RT-qPCR and western blotting, respectively. Comparing with the control shRNA group, the ESCO2 shRNA-1(p < 0.001) and ESCO2 shRNA-2 (p < 0.001) groups had significantly decreased ESCO2 mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 3a). Comparing with the control shRNA group, the ESCO2 shRNA-1and ESCO2 shRNA-2 groups had alsoobviouslydecreased ESCO2 protein expression (Fig. 3b). ESCO2 silencing significantly inhibited cell growth (Fig. 3c), migration and invasion (Fig. 3d), and colony formation (Fig. 3e) in both the NCI-H1975 and A549 cells.

Fig. 3.

Stable silencing of ESCO2 expression inhibits the malignant phenotype of LUAD cells in vitro, and growth and metastasis in vivo. a and b ESCO2 expression was stably silenced using shRNA; ESCO2 mRNA and protein expression levels in NCI-H1975 and A549 cells were detected by q-PCR (a) and western blotting (b), respectively. c–e The effects of ESCO2 stable silencing on LUAD cell growth (c), migration and invasion (d), and colony formation (e) were detected. f The in vivo growth of NCI-H1975 cell lines with ESCO2 stable silencing was detected (n = 6). g NOD-SCID mice (n = 5) were transplanted with Luc-labeled NCI-H1975 cells (2 × 106 cells/mouse) with ESCO2 stable silencing to detect in vivo metastasis ability. h The lung metastatic nodule number was analyzed. Data are the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001

In addition, we observed that, contrary to the control shRNA, NCI-H1975 cells with ESCO2 stable silencing had lower tumor volumes and significantly decreased tumor weights (p < 0.0001; Fig. 3f). ESCO2 stable silencing also suppressed metastasis ability in vivo (Fig. 3g). At the same time, analysis of the lung metastatic nodule number showed that the ESCO2 shRNA-1 group had significantly decreased metastatic nodules (p = 0.0025; Fig. 3h).

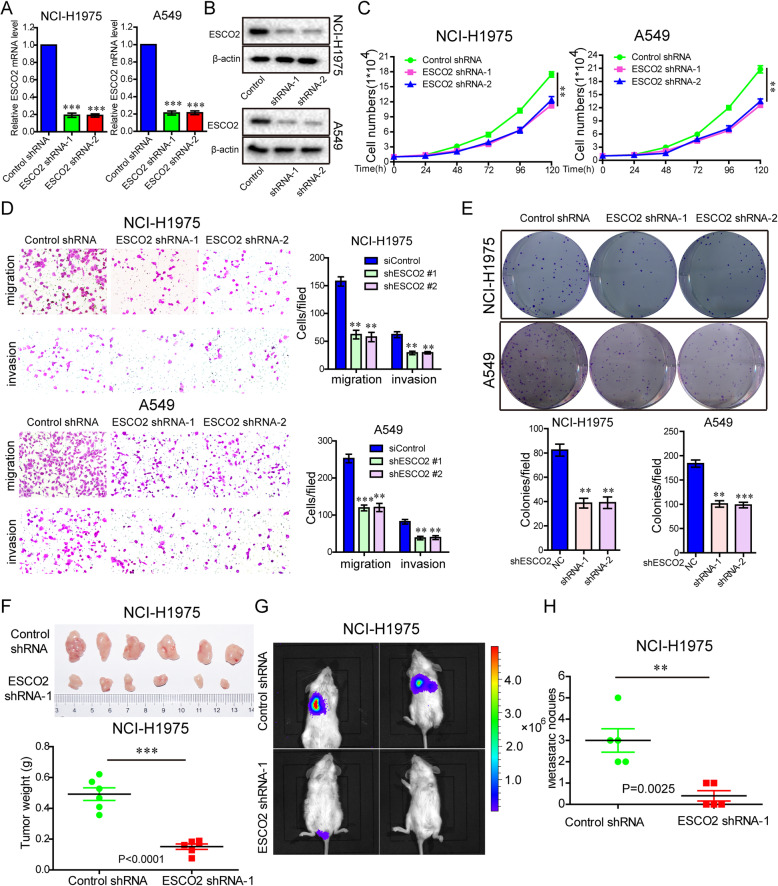

ESCO2 acetylated hnRNPA1 at K277

The mechanism of ESCO2 action in LUAD progression was investigated using immunoprecipitation, silver staining, and MS, and 32ESCO2-binding proteins were identified (Fig. 4a and Table S2). The GSEA plot indicated that enrichment of the spliceosome-related genes was significantly correlated to high ESCO2 mRNA expression levels in TCGA LUAD cohort (p < 0.001; Fig. 4b and c). The MS showed that hnRNPA1 had a high mass spectrum score (Table S2), and GSEA results and previous study showed that it is an important splicing regulator [27]. According to the results of the MS and GSEA, we found hnRNP A1 to be particularly interesting. To determine the interaction between ESCO2 and hnRNPA1, the ESCO2-FLAG vector was transfected into NCI-H1975 cells, the ESCO2-FLAG complexes underwent Co-IP, and then hnRNPA1 in the complexes was detected (Fig. 4d). NCI-H1975 cells were transfected with hnRNPA1-HAplasmids, the hnRNPA1-HA complexes underwent Co-IP, and then ESCO2 in the complexes was detected (Fig. 4e). As ESCO2 is an evolutionarily conserved cohesion acetyltransferase, we examined whether ESCO2 acetylates hnRNPA1 by co-transfecting NCI-H1975 cells with hnRNPA1-HAand ESCO2-FLAGvectors, followed by immunoprecipitation by anti-HA antibody, and detection using the pan-specific anti-acetylated lysineantibody. The hnRNPA1 acetylation levels were increased (Fig. 4f), suggesting that ESCO2 can acetylate hnRNPA1 protein. In addition, compared with the NC group, the hnRNPA1 acetylation levels in the shESCO2 group was decreased significantly (Fig. 4g). Co-IP confirmed that there was an interaction between ESCO2 and hnRNPA1 protein and that ESCO2 could acetylate hRNPA1 protein, but the acetylation site was not known. The acetylation site was identified by Co-IP combined with MS (Fig. 4g and Fig. S1), and was revealed to be on lysine (K) at site 277. To investigate whether the acetylation site is at K277, hnRNPA1 WT (wild-type) or K277R mutant plasmids were co-transfected with ESCO2-FLAG into NCI-H1975 cells, and acetylation levels were detected using anti–ac-K antibody. We found that the K277R mutant decreased ac-K expression (Fig. 4i). In addition, the K277R mutation influenced the interaction between ESCO2 and hnRNPA1 (Fig. 4j and k). To prove that ESCO2 specifically regulates hnRNPA1 acetylation, recombinant WT hnRNPA1 and its K277R mutant were incubated with recombinant ESCO2, and acetylation levels were detected using anti–ac-K antibody. The acetylation level significantly reduced in the K277R group (Fig. 4l). Collectively, our results indicate that ESCO2 binds to hnRNPA1 and regulates its acetylation. The acetylation site is at K277, which determines the interaction and acetylation between ESCO2 and hnRNPA1.

Fig. 4.

Interaction of ESCO2 with hnRNPA1 acetylates hnRNPA1 at K277. a ESCO2-FLAG vector was transfected into HEK293T cells, the ESCO2-FLAG complexes underwent Co-IP, and then ESCO2-binding proteins were identified by combined silver staining and MS. b Enrichment plot showing enrichment of spliceosome-related genes in the ESCO2 high-expression group in TCGA LUAD cohort. c Heatmap showing the relative expression values for 126 spliceosome-related genes in TCGA LUAD cohort. d The ESCO2-FLAG vector was transfected into NCI-H1975 cells, the ESCO2-FLAG complexes underwent Co-IP, and then hnRNPA1 in the complexes was detected. e hnRNPA1-HAplasmids were transfected into NCI-H1975 cells, the hnRNPA1-HA complexes underwent Co-IP, and then ESCO2 in the complexes was detected. f NCI-H1975 cells were simultaneously transfected with hnRNPA1-HAand ESCO2-FLAGvectors, immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibody, and then detection was performed using anti–ac-K antibody. g NCI-H1975 cells with ESCO2 stable silencing were transfected with hnRNPA1-HA vector, immunoprecipitated by anti-HA antibody, and then detection was performed using anti–ac-K antibody. h The K277 acetylation site was identified by MS. i hnRNPA1 WT or K277R mutant plasmids were co-transfected with ESCO2-FLAG into NCI-H1975 cells, and acetylation levels were detected using anti–ac-K antibody. j and k hnRNPA1 WT or K277R mutant plasmids were co-transfected with ESCO2-FLAG into NCI-H1975 cells, anti-HA antibody was used for Co-IP, and ESCO2-FLAG was detected using anti-FLAG antibody (j); anti-FLAG antibody was used for Co-IP, and hnRNPA1 WT and K277R mutant constructs were detected using anti-HA antibody (k). Recombinant WT hnRNPA1 and its mutant K277R were incubated with recombinant ESCO2, and acetylation levels were detected using anti–ac-K antibody

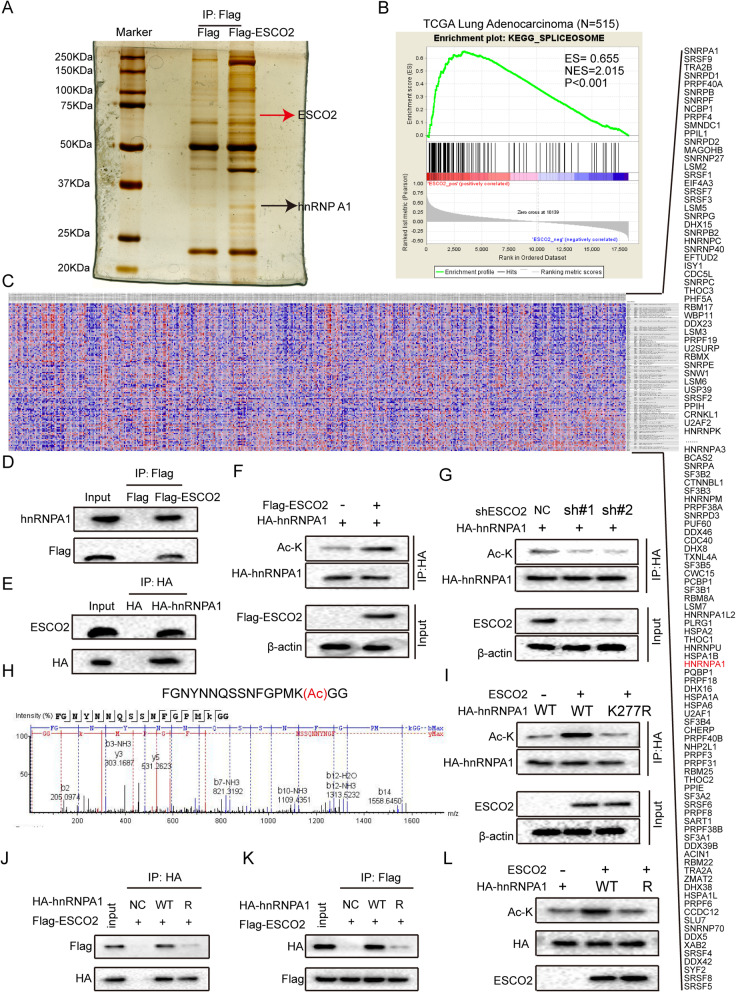

ESCO2 acetylates hnRNPA1 at K277 to promote the aggressive phenotype of LUAD cells

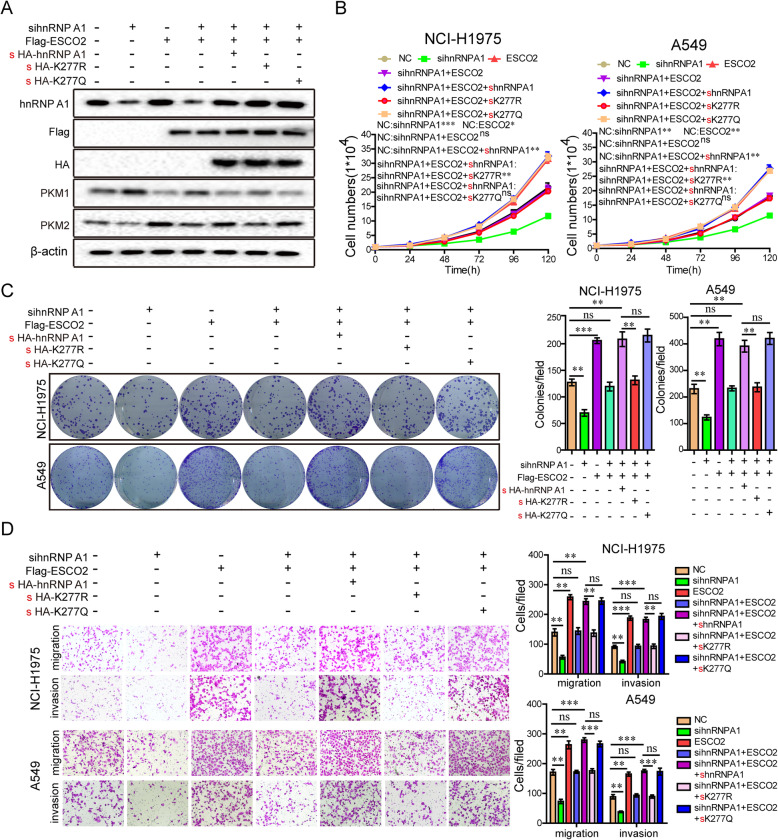

Next, we explore whether ESCO2 promotes the malignant phenotype of LUAD cells by acetylating the K277 site of hnRNP A1.By knocking down the expression of hnRNPA1 by siRNA, the effect of the background expression of hnRNP A1 was eliminated. The hnRNPA1 siRNAs (small interfering RNAs) together with ESCO2 plasmids were transfected into LUAD cells, and hnRNPA1 expression was restored using WT hnRNPA1 and the mutant K277R and K277Q plasmids (Fig. 5a). Compared with the NC group, silencing hnRNPA1 significantly suppressed LUAD cell growth, colony formation, migration, and invasion in the NCI-H1975 and A549 cells (Fig. 5b–d). Furthermore, silencing hnRNPA1 antagonized the enhancement of LUAD cell growth, colony formation, migration, and invasion induced by ESCO2 overexpression, indicating that ESCO2 promotes malignant progression through hnRNPA1 (Fig. 5b–d). Interestingly, when the WT hnRNPA1 vector or hnRNPA1 K277Q mutant restored hnRNPA1 expression in the LUAD cells, ESCO2 significantly promotes the malignant phenotype of LUAD cells, but not in the hnRNPA1 K277R mutant condition, as ESCO2 could not acetylate it (Fig. 5b–d). Collectively, these data show that ESCO2 promotes LUAD cell proliferation and metastasis by acetylating the oncoprotein hnRNPA1 at K277.

Fig. 5.

ESCO2 acetylates hnRNPA1 at K277, promoting the malignant phenotype of LUAD cells. After 36-h transfection of hnRNPA1 siRNAs into LUAD cells, the cells were transfected with WT hnRNPA1 and its mutant K277R and K277Q plasmids, together with ESCO2 plasmids. Protein levels (a) and cell growth (b), migration (c), invasion (c), and colony formation (d) were detected. Data are the mean ± SD. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 or ***p < 0.001

ESCO2 increases hnRNPA1 binding to the intronic sequences flanking exon 9 (EI9) of PKM mRNA by inhibiting hnRNPA1 nuclear export

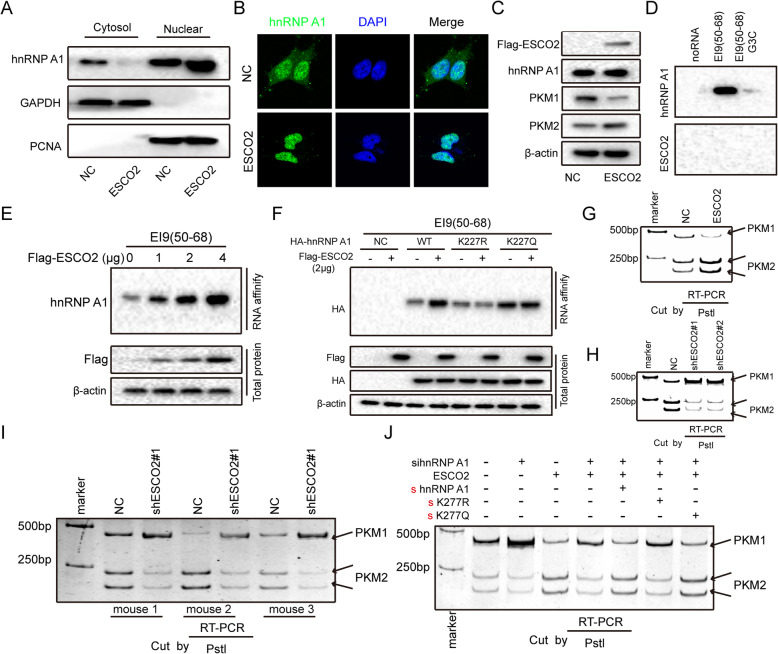

The K277 site of hnRNPA1 is located in the M9 domain, which mediates hnRNPA1 nuclear transport [28, 29]. Therefore, we investigated if hnRNPA1 acetylation by ESCO2 affects its nuclear localization. The ESCO2-FLAGplasmid was transfected into NCI-H1975 cells; the nucleus and cytoplasm were separated. hnRNPA1 expression in the ESCO2 overexpression cells was upregulated in the nucleus, and was downregulated in the cytosol (Fig. 6a). Immunofluorescence staining indicated that ESCO2 overexpression retained hnRNPA1 in the nucleus (Fig. 6b). ESCO2 overexpression upregulated PKM2 protein expression levels and downregulated PKM1 protein expression levels, but did not change hnRNPA1 expression levels (Fig. 6c).

Fig. 6.

ESCO2 increases hnRNPA1 binding to the EI9 of PKM mRNA by inhibiting hnRNPA1 nuclear export, eventually inhibiting PKM1 isoform formation and inducing PKM2 isoform formation. a–c ESCO2-FLAGplasmid was transfected into NCI-H1975 cells; the nucleus and cytoplasm were separated, and then hnRNPA1 was detected using western blotting (a). Anti-hnRNPA1 antibody was used to detect the subcellular localization of hnRNPA1 (green) (b). Protein levels were detected using western blotting (c). d NCI-H1975 nuclear extracts were affinity-purified using biotin-labeled RNAs, and then ESCO2 and hnRNPA1 were detected. e ESCO2-FLAG vector was transfected into NCI-H1975 cells, RNA affinity purification was performed using biotin-labeled RNA EI9 (50–68), and then hnRNPA1 was detected. f WT hnRNPA1 and its mutant K277R and K277Q plasmids together with ESCO2 plasmids were co-transfected into NCI-H1975 cells, and RNA affinity purification was performed as in (d), and then hnRNPA1 was detected. g–j PKM splicing assay was performed by combining RT-PCR with PstI. g ESCO2-FLAG vector was transfected into NCI-H1975 cells, and then PKM splicing assay was performed. h The PKM splicing of NCI-H1975 cells with ESCO2 stable silencing was detected. i PKM splicing was performed in mouse xenograft tumors (n = 3). j After 36-h transfection of hnRNPA1 siRNAs into NCI-H1975 cells, the cells were transfected with WT hnRNPA1 and its mutant K277R and K277Q plasmids together with ESCO2 plasmids, and then the PKM splicing assay was performed

hnRNPA1 restricts the inclusion of PKM exon 9, promoting PKM2 formation and inhibiting PKM1 formation, by binding to the UAGGGC sequences of exon 9 [23, 30]. RNA pull-down experiments showed that hnRNPA1 can strongly bind to the PKM EI9 (50–68) sequence, and when the G3 nucleotide of EI9 (50–68) is mutated to C, its ability to bind to hnRNPA1 is significantly reduced (Fig. 6d). At the same time, ESCO2 did not directly bind to the EI9 (50–68) sequence (Fig. 6d). Moreover, ESCO2 increased hnRNPA1 and PKM EI9 (50–68) binding in a dose-dependent manner in the nucleus (Fig. 6e). To investigate whether ESCO2 increases hnRNPA1 to PKM EI9 (50–68) binding by acetylating hnRNPA1, we transfected hnRNPA1 siRNAs into NCI-H1975 cells for 36 h, and then co-transfected the cells with WT hnRNPA1 and its mutant K277R and K277Q plasmids together with ESCO2 plasmids RNA pull-down using biotin-labeled EI9 (50–68) RNA showed that that ESCO2 promoted the binding of WT hnRNPA1 to PKM EI9 (50–68), but not that of the K277R mutant. In addition, compared to the WT hnRNPA1, the K277Q mutant had higher affinity with PKM EI9 (50–68), and ESCO2 overexpression did not increase hnRNPA1 binding to PKM EI9 (50–68) (Fig. 6f). Next, we used RT-PCR and PstI restriction digestion to investigate whether ESCO2 regulates alternative splicing of PKM pre-mRNA. ESCO2 overexpression decreased PKM1 isoform mRNA levels and increased that of the PKM2 isoform (Fig. 6g). Silencing ESCO2 decreased PKM2 isoform mRNA levels and increased that of the PKM1 isoform (Fig. 6h); the same results were obtained for PKM splicing in the mouse xenograft tumors (n = 3) (Fig. 6i). Compared with the NC group, silencing hnRNPA1 suppressed PKM2 isoform mRNA levels and increased that of the PKM1 isoform, and silencing hnRNPA1 antagonized the splicing change of PKM pre-mRNA induced by ESCO2 overexpression (Fig. 6j). Furthermore, when the WT hnRNPA1 vector or hnRNPA1 K277Q mutant restored hnRNPA1 expression in the LUAD cells, ESCO2 could decrease PKM1 isoform mRNA levels and increased that of the PKM2 isoform, but not in the hnRNPA1 K277R mutant condition. Collectively, these data show that ESCO2 increases hnRNPA1 binding to the EI9 of PKM mRNA by inhibiting hnRNPA1 nuclear translocation, eventually inhibiting PKM1 isoform formation and inducing PKM2 isoform formation.

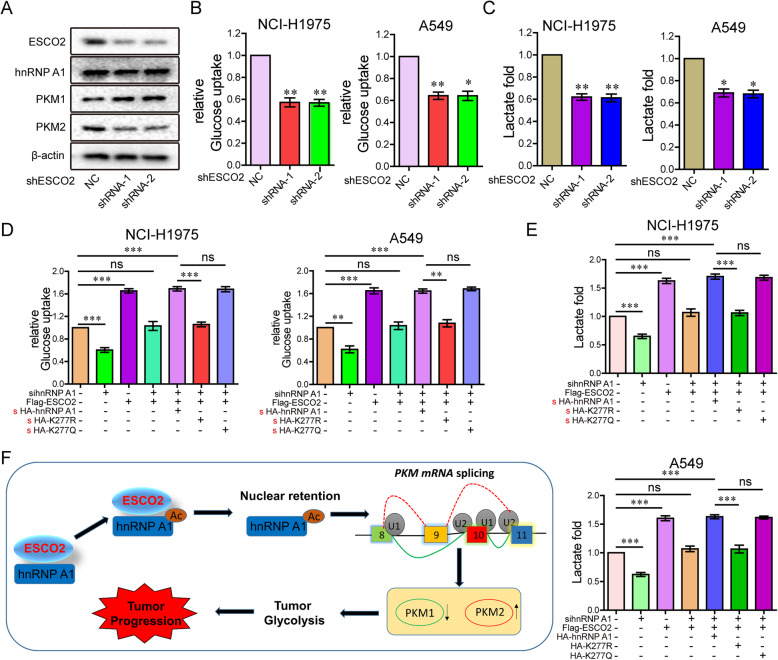

ESCO2 promotes aerobic glycolysis of LUAD cells by increasing PKM2 expression and decreasing PKM1 expression

The PKM2 isozyme is a key promoter of the Warburg effect in tumors, which is characterized by increased glucose uptake and lactic acid production [31]. PKM protein levels were detected in NCI-H1975 cells with ESCO2 stable silencing, and showed that PKM1 expression was obviously increased, while PKM2 expression was obviously decreased (Fig. 7a). Silencing ESCO2 significantly decreased glucose uptake and lactate production in the LUAD cells (Fig. 7b and c). In addition, ESCO2 overexpression significantly increased glucose uptake and lactate production in the LUAD cells (Fig. S2). Compared with the NC group, silencing hnRNPA1 also significantly decreased glucose uptake and lactate production, and antagonized the glucose uptake and lactate production promoted by ESCO2 overexpression (Fig. 7d and e). Furthermore, when the WT hnRNPA1 vector or hnRNPA1 K277Q mutant restored hnRNPA1 expression in the LUAD cells, ESCO2 significantly promotes glucose uptake and lactate production, but not in the hnRNPA1 K277R mutant condition (Fig. 7d and e). The working model of ESCO2 promoted aerobic glycolysis and drove malignant progression by acetylating hnRNPA1 (Fig. 7f).

Fig. 7.

ESCO2 promotes aerobic glycolysis of LUAD cells by increasing PKM2 expression and decreasing PKM1 expression. a Protein levels were detected in NCI-H1975 cells with ESCO2 stable silencing. b and c Glucose uptake (b) and lactate production (c) were measured in LUAD cells with ESCO2 stable silencing. d and e After 36-h transfection with hnRNPA1 siRNAs into LUAD cells, the cells were transfected with WT hnRNPA1 and its mutant K277R and K277Q plasmids together with ESCO2 plasmids, and then glucose uptake (d) and lactate production (e) were examined. f The working model of ESCO2 promotes aerobic glycolysis and drives tumorigenesis by acetylating hnRNPA1

Discussion

In the present study, literature and database analyses showed that ESCO2 has a significant correlation with malignant progression of LUAD. Here, comparison of tumor-adjacent normal lung tissue via analysis of the Oncomine, GEO and TCGA datasets showed that ESCO2 mRNA and protein expression levels were upregulated in LUAD tissues. GSEA showed that the cell cycle signatures and DNA replication signatures had a significant positive correlation with ESCO2 mRNA expression levels in TCGA LUAD cohort. Our results show that The ESCO2 overexpression NCI-H1975 and A549 cells had greater cell growth and greater invasive, migration, and colony-formation ability, while silencing ESCO2 had the opposite effect. Furthermore, ESCO2 stable silencing decreased the tumor growth and pulmonary metastasis of the NCI-H1975 cells in vivo. Chen et al. discovered that ESCO2 knockdown dramatically inhibited cell proliferation and induced apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells, and suppressed tumor xenograft development in vivo [19]. In addition, significantly high ESCO2 expression was found in renal cell carcinoma tissue and cell lines, promoting cell aggressive behaviors and inducing poor prognosis [15]. Therefore, together with other research data, our data indicate that ESCO2 plays a key role in the proliferation and metastasis of many types of human cancer.

Furthermore, we found that ESCO2 could interact with hnRNPA1 and acetylates hnRNPA1 at K277. hnRNPA1 regulates alternative splicing of interferon regulatory factor 3 and affects immunomodulatory functions in human non–small cell lung cancer cells [32]. hnRNPA1 plays a crucial role in regulating cell proliferation, invasiveness, metabolism, and immortalization in multiple tumors such as hepatocellular carcinoma, prostate cancer, and oral squamous cell cancer [33–35]. In the present study, silencing hnRNPA1 antagonized the enhancement of LUAD cell growth, colony formation, migration, and invasion induced byESCO2 overexpression. The data suggest that the ESCO2 and hnRNPA1 interaction promotes the malignant progression of LUAD.

Here, we discovered a novel acetylated substrate, hnRNPA1, of the acetyltransferase ESCO2. Furthermore, we found that ESCO2 acetylates hnRNPA1 at K277 and inhibits the nuclear export of hnRNPA1. In addition, hnRNPA1 mediated the regulation of PKM splicing by blocking the binding of the arginine residues in the RGG motif of hnRNPA1 to the PKM EI9, ensuring the formation of PKM2 and suppressing glucose metabolism reprogramming [26]. We discovered that ESCO2 increased hnRNPA1 binding to the EI9 of PKM mRNA by inhibiting hnRNPA1 nuclear translocation, leading to increased PKM2 expression and decreased PKM1 expression.

We also elucidated the function and mechanism of ESCO2 in glucose metabolism in LUAD cells. ESCO2 promoted aerobic glycolysis of LUAD cells by increasing PKM2 expression and decreasing PKM1 expression. PKM is a glycolytic enzyme that catalyzes the final step in glycolysis, and exists in two different forms: PKM1 and PKM2. PKM1 is distributed in high energy–demand organs, such as brain and muscle. PKM2 is believed to be one of the most important genes in cancer-specific energy metabolism, known as the Warburg effect [36]. Most cancer cells such as that of colon cancer, bladder cancer, and pancreatic cancer express PKM2 dominantly to maintain a glycolysis-dominant energy metabolism [24, 37–39]. PKM2 reduces the glucose levels for intracellular utilization, in particular citrate production, thereby increasing the α-ketoglutarate/citrate ratio to promote the generation of glutamine-derived acetyl-coenzyme A through the reductive pathway. In addition, reductive glutamine metabolism promotes cell proliferation under hypoxia conditions and supports in vivo tumor growth [40]. Therefore, we have found and proven that ESCO2 is an important functional molecule that promotes metabolic reprogramming of LUAD. The ESCO2-cohesin complex links DNA molecules and plays important roles in the gene transcription of eukaryotic genomes. Sadia Rahman and their colleagues have found that Esco2 binding sites are enriched for CTCF and REST/NRSF transcription factor motifs [41]. In addition, ESCO2 can regulate transcription of neuron-specific genes in other tissues [42, 43]. These studies show that ESCO2 is closely related to RNA transcription regulation. Whether ESCO2 promotes the malignant progression of lung adenocarcinoma by regulating gene transcription and its specific regulatory mechanisms, this will be the focus of our further research.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patients with LUAD with high ESCO2 mRNA and protein expression levels have lower OS and recurrence-free survival, as compared with patients with low ESCO2 expression levels. A novel role for ESCO2 in LUAD tumorigenesis has been elucidated, that is, ESCO2 upregulation promotes cell growth, proliferation, colony formation, and cell cycle progression. Moreover, ESCO2 can interact with hnRNPA1 and acetylates it at K277, retaining it in the nucleus. In addition, ESCO2 promotes hnRNPA1 binding to the EI9 of PKM mRNA by inhibiting hnRNPA1 nuclear translocation. Furthermore, ESCO2 promotes aerobic glycolysis of LUAD cells by increasing PKM2 expression and decreasing PKM1 expression. Therefore, ESCO2 may serve as a new therapeutic target for LUAD.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. (A) hnRNPA1-HA vector was transfected into HEK293T cells, the hnRNPA1-HA complexes underwent Co-IP, and then protein modification of hnRNPA1 was identified by Coomassie blue staining with MS.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure 2. (A-B) ESCO2-FLAG vector was transfected into NCI-H1975 cells, and then Glucose uptake (A) and lactate production (B) were measured.DD.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table S1. The antibodies, primers , oligonucleotides and shRNAs used in this study are shown.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table S2.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ESCO2

Establishment of cohesion 1 homolog 2

- hnRNPA1

Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein A1

- LUAD

Lung adenocarcinoma

- Co-IP

Coimmunoprecipitation

- MS

Mass spectrometry

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

Authors’ contributions

HC and WPC conceived and designed the experiments. HEZ, and WPC analyzed the data, HEZand SNS prepared the manuscript. HEZ, TL andSNS performed the experiments. HC and DXC provided statistical support and analyzed the IHC data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University Youth fund (grant no.2018Q19 and 2019Q2).

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in thispublished article.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the thirdAffiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hui-er Zhu, Tao Li and Shengnan Shi contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Weiping Chen, Email: 1806973726@qq.com.

Hui Chen, Email: chenhui7320@126.com.

References

- 1.Lambe G, Durand M, Buckley A, Nicholson S, McDermott R. Adenocarcinoma of the lung: from BAC to the future. Insights Imaging. 2020;11(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s13244-020-00875-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liang W, Zhang L, Jiang G, Wang Q, Liu L, Liu D, et al. Development and validation of a nomogram for predicting survival in patients with resected non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(8):861–869. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.6661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, Zhang S, Zeng H, Bray F, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–132. doi: 10.3322/caac.21338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhu HE, Yin JY, Chen DX, He S, Chen H. Agmatinase promotes the lung adenocarcinoma tumorigenesis by activating the NO-MAPKs-PI3K/Akt pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10(11):854. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2082-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shaw AT, Solomon BJ, Besse B, Bauer TM, Lin CC, Soo RA, et al. ALK resistance mutations and efficacy of Lorlatinib in advanced anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(16):1370–1379. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi K, Soejima K, Fukunaga K, Shintani Y, Sekine I, Shukuya T, et al. Key prognostic factors for EGFR-mutated non-adenocarcinoma lung cancer patients in the Japanese joint Committee of Lung Cancer Registry Database. Lung Cancer. 2020;146:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen JA, Riess JW. Optimal Management of Patients with advanced NSCLC harboring high PD-L1 expression and driver mutations. Curr Treat Options in Oncol. 2020;21(7):60. doi: 10.1007/s11864-020-00750-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sankar K, Gadgeel SM, Qin A. Molecular therapeutic targets in non-small cell lung cancer. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2020;20(8):647–661. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2020.1787156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Noor ZS, Cummings AL, Johnson MM, Spiegel ML, Goldman JW. Targeted therapy for non-small cell lung Cancer. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41(3):409–434. doi: 10.1055/s-0039-1700994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gu J, Yao W, Shi P, Zhang G, Owonikoko TK, Ramalingam SS, et al. MEK or ERK inhibition effectively abrogates emergence of acquired osimertinib resistance in the treatment of epidermal growth factor receptor-mutant lung cancers. Cancer. 2020;126(16):3788–3799. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvayrac O, Pradines A, Pons E, Mazieres J, Guibert N. Molecular biomarkers for lung adenocarcinoma. Eur Respir J. 2017;49(4):1601734. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01734-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Testa U, Castelli G, Pelosi E. Lung Cancers: Molecular Characterization, Clonal Heterogeneity and Evolution, and Cancer Stem Cells. Cancers (Basel) 2018;10(8):248. doi: 10.3390/cancers10080248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alomer RM, da Silva EML, Chen J, Piekarz KM, McDonald K, Sansam CG, et al. Esco1 and Esco2 regulate distinct cohesin functions during cell cycle progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(37):9906–9911. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1708291114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo XB, Huang B, Pan YH, Su SG, Li Y. ESCO2 inhibits tumor metastasis via transcriptionally repressing MMP2 in colorectal cancer. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:6157–6166. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S181265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang QL, Liu L. Establishment of cohesion 1 homolog 2 facilitates cell aggressive behaviors and induces poor prognosis in renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Lab Anal. 2020;34(5):e23163. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xiao B, Chen L, Ke Y, Hang J, Cao L, Zhang R, et al. Identification of methylation sites and signature genes with prognostic value for luminal breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2018;18(1):405. doi: 10.1186/s12885-018-4314-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang W, Cui Q, Qu W, Ding X, Jiang D, Liu H. TRIM58/cg26157385 methylation is associated with eight prognostic genes in lung squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2018;40(1):206–216. doi: 10.3892/or.2018.6426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryu B, Kim DS, Deluca AM, Alani RM. Comprehensive expression profiling of tumor cell lines identifies molecular signatures of melanoma progression. PLoS One. 2007;2(7):e594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen H, Zhang L, He W, Liu T, Zhao Y, Chen H, et al. ESCO2 knockdown inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in human gastric cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;496(2):475–481. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kedzierska H, Piekielko-Witkowska A. Splicing factors of SR and hnRNP families as regulators of apoptosis in cancer. Cancer Lett. 2017;396:53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kutluay SB, Emery A, Penumutchu SR, Townsend D, Tenneti K, Madison MK, et al. Genome-Wide Analysis of Heterogeneous Nuclear Ribonucleoprotein (hnRNP) Binding to HIV-1 RNA Reveals a Key Role for hnRNP H1 in Alternative Viral mRNA Splicing. J Virol. 2019;93(21):e01048–e01019. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01048-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Luo W, Semenza GL. Emerging roles of PKM2 in cell metabolism and cancer progression. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23(11):560–566. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.David CJ, Chen M, Assanah M, Canoll P, Manley JL. HnRNP proteins controlled by c-Myc deregulate pyruvate kinase mRNA splicing in cancer. Nature. 2010;463(7279):364–368. doi: 10.1038/nature08697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuranaga Y, Sugito N, Shinohara H, Tsujino T, Taniguchi K, Komura K, et al. SRSF3, a Splicer of the PKM Gene, Regulates Cell Growth and Maintenance of Cancer-Specific Energy Metabolism in Colon Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(10):3012. doi: 10.3390/ijms19103012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Robbins Y, Greene S, Friedman J, Clavijo PE, Van Waes C, Fabian KP, et al. Tumor control via targeting PD-L1 with chimeric antigen receptor modified NK cells. Elife. 2020;9:e54854. doi: 10.7554/eLife.54854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang JZ, Chen M, Chen D, Gao XC, Zhu S, Huang H, et al. A peptide encoded by a putative lncRNA HOXB-AS3 suppresses Colon Cancer growth. Mol Cell. 2017;68(1):171–184. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chabot B, LeBel C, Hutchison S, Nasim FH, Simard MJ. Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle a/B proteins and the control of alternative splicing of the mammalian heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle A1 pre-mRNA. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2003;31:59–88. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-09728-1_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Izaurralde E, Jarmolowski A, Beisel C, Mattaj IW, Dreyfuss G, Fischer U. A role for the M9 transport signal of hnRNP A1 in mRNA nuclear export. J Cell Biol. 1997;137(1):27–35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iijima M, Suzuki M, Tanabe A, Nishimura A, Yamada M. Two motifs essential for nuclear import of the hnRNP A1 nucleocytoplasmic shuttling sequence M9 core. FEBS Lett. 2006;580(5):1365–1370. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.01.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen M, David CJ, Manley JL. Concentration-dependent control of pyruvate kinase M mutually exclusive splicing by hnRNP proteins. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(3):346–354. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen M, Sheng XJ, Qin YY, Zhu S, Wu QX, Jia L, et al. TBC1D8 amplification drives tumorigenesis through metabolism reprogramming in ovarian Cancer. Theranostics. 2019;9(3):676–690. doi: 10.7150/thno.30224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo R, Li Y, Ning J, Sun D, Lin L, Liu X. HnRNP A1/A2 and SF2/ASF regulate alternative splicing of interferon regulatory factor-3 and affect immunomodulatory functions in human non-small cell lung cancer cells. PLoS One. 2013;8(4):e62729. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang H, Zhu R, Zhao X, Liu L, Zhou Z, Zhao L, et al. Sirtuin-mediated deacetylation of hnRNP A1 suppresses glycolysis and growth in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncogene. 2019;38(25):4915–4931. doi: 10.1038/s41388-019-0764-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carabet LA, Leblanc E, Lallous N, Morin H, Ghaidi F, Lee J, et al. Computer-Aided Discovery of Small Molecules Targeting the RNA Splicing Activity of hnRNP A1 in Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. Molecules. 2019;24(4):763. doi: 10.3390/molecules24040763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yu C, Guo J, Liu Y, Jia J, Jia R, Fan M. Oral squamous cancer cell exploits hnRNP A1 to regulate cell cycle and proliferation. J Cell Physiol. 2015;230(9):2252–2261. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taniguchi K, Sugito N, Shinohara H, Kuranaga Y, Inomata Y, Komura K, et al. Organ-Specific MicroRNAs (MIR122, 137, and 206) Contribute to Tissue Characteristics and Carcinogenesis by Regulating Pyruvate Kinase M1/2 (PKM) Expression. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(5):1276. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Massari F, Ciccarese C, Santoni M, Iacovelli R, Mazzucchelli R, Piva F, et al. Metabolic phenotype of bladder cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016;45:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Calabretta S, Bielli P, Passacantilli I, Pilozzi E, Fendrich V, Capurso G, et al. Modulation of PKM alternative splicing by PTBP1 promotes gemcitabine resistance in pancreatic cancer cells. Oncogene. 2016;35(16):2031–2039. doi: 10.1038/onc.2015.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao X, Zhu Y, Hu J, Jiang L, Li L, Jia S, et al. Shikonin inhibits tumor growth in mice by suppressing pyruvate kinase M2-mediated aerobic glycolysis. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):14517. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-31615-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu M, Wang Y, Ruan Y, Bai C, Qiu L, Cui Y, et al. PKM2 promotes reductive glutamine metabolism. Cancer Biol Med. 2018;15(4):389–399. doi: 10.20892/j.issn.2095-3941.2018.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rahman S, Jones MJ, Jallepalli PV. Cohesin recruits the Esco1 acetyltransferase genome wide to repress transcription and promote cohesion in somatic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(36):11270–11275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1505323112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ooi L, Wood IC. Chromatin crosstalk in development and disease: lessons from REST. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8(7):544–554. doi: 10.1038/nrg2100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Qureshi IA, Gokhan S, Mehler MF. REST and CoREST are transcriptional and epigenetic regulators of seminal neural fate decisions. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(22):4477–4486. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.22.13973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. (A) hnRNPA1-HA vector was transfected into HEK293T cells, the hnRNPA1-HA complexes underwent Co-IP, and then protein modification of hnRNPA1 was identified by Coomassie blue staining with MS.

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure 2. (A-B) ESCO2-FLAG vector was transfected into NCI-H1975 cells, and then Glucose uptake (A) and lactate production (B) were measured.DD.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table S1. The antibodies, primers , oligonucleotides and shRNAs used in this study are shown.

Additional file 4: Supplementary Table S2.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in thispublished article.