Abstract

Background

PET imaging of glucose metabolism has revealed presymptomatic abnormalities in genetic FTD but has not been explored in MAPT P301L mutation carriers. This study aimed to explore the patterns of presymptomatic hypometabolism and atrophy in MAPT P301L mutation carriers.

Methods

Eighteen asymptomatic members from five families with a P301L MAPT mutation were recruited to the study, six mutation carriers, and twelve mutation-negative controls. All participants underwent standard behavioural and cognitive assessment as well as [18F]FDG-PET and 3D T1-weighted MRI brain scans. Regional standardised uptake value ratios (SUVR) for the PET scan and volumes calculated from an automated segmentation for the MRI were obtained and compared between the mutation carrier and control groups.

Results

The mean (standard deviation) estimated years from symptom onset was 12.5 (3.6) in the mutation carrier group with a range of 7 to 18 years. No differences in cognition were seen between the groups, and all mutation carriers had a global CDR plus NACC FTLD of 0. Significant reduction in [18F] FDG uptake in the anterior cingulate was seen in mutation carriers (mean 1.25 [standard deviation 0.07]) compared to controls (1.36 [0.09]). A similar significant reduction was also seen in grey matter volume in the anterior cingulate in mutation carriers (0.60% [0.06%]) compared to controls (0.68% [0.08%]). No other group differences were seen in other regions.

Conclusions

Anterior cingulate hypometabolism and atrophy are both apparent presymptomatically in a cohort of P301L MAPT mutation carriers. Such a specific marker may prove to be helpful in stratification of presymptomatic mutation carriers in future trials.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13195-021-00777-9.

Keywords: PET imaging, Glucose metabolism, Presymptomatic, Frontotemporal dementia

Background

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) describes a clinically, genetically and pathologically heterogenous group of diseases characterised by degeneration of the frontal and temporal cortices [30]. Approximately a third of all FTD is genetic, with the first described cause being mutations in the microtubule-associated protein tau (MAPT) gene in 1998 [13, 22, 27]. Over 70 pathogenic mutations have since been discovered, with the most common being the P301L mutation in exon 10 [19].

In recent years, several studies have identified presymptomatic changes in genetic FTD using a range of neuroimaging techniques, although the majority of these have focused on structural, functional or perfusion magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [6, 9–11, 21, 24]. Studies of positron emission tomography (PET) imaging have been more limited, and mainly focused on [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG-PET), a measure of glucose metabolism in vivo, where hypometabolism is thought to reflect neuronal dysfunction. In limited studies so far, FDG-PET has revealed presymptomatic abnormalities in other genetic causes of FTD [2, 7, 8, 14], but not in P301L MAPT mutation carriers.

In this study, we aimed to investigate whether presymptomatic neuronal dysfunction is present in P301L MAPT mutation carriers as measured by FDG-PET, and whether patterns of hypometabolism differed from patterns of atrophy.

Methods

Participants

Eighteen asymptomatic participants were recruited from five families with an autosomal dominant P301L mutation in the MAPT gene through the Quebec City (Canada) site of the Genetic Frontotemporal dementia Initiative (GENFI) study. All participants underwent genetic screening with 6 found to be carriers of the mutation, and 12 found to be mutation-negative, and therefore used as controls in this study. There were no significant differences in age (p = 0.98) or sex (p = 0.32) between groups. Participants and investigators were blinded to individual genetic statuses. The study was approved by the CHU de Québec-Université Laval (Québec City, Canada) research ethics board. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before any study-related procedures.

Clinical assessment

Each participant underwent a standardised assessment (Table 1) including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB) and the CDR® Dementia Staging Instrument with National Alzheimer Coordinating Centre Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration component (CDR® plus NACC FTLD) which generates both global and sum of boxes scores. Estimated years from symptom onset were calculated for each participant as the current age taken away from the mean age at onset within the participant’s family [19] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics, behavioural and cognitive features in P301L MAPT mutation carriers (n = 6) and controls (n = 12)

| Mutation carriers, mean (SD) | Controls, mean (SD) | U | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 44.8 (6.3) | 46.1 (7.2) | 35.50 | 0.98 |

| Sex (male:female) | 1:5 | 6:6 | N/A | 0.32 |

| Estimated years from symptom onset | 12.5 (3.6), range: 7–18 years | 9.5 (9.1), range: − 5.5–29 years | 24.50 | 0.30 |

| Years of education | 16.3 (2.3) | 14.4 (2.2) | 21.50 | 0.17 |

| CDR with NACC FTLD sum of boxes | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.2) | 30.00 | 0.53 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination (/30) | 29.8 (0.4) | 29.8 (0.5) | 33.00 | > 0.99 |

| Montreal Cognitive Assessment (/30) | 28.5 (1.8) | 28.3 (1.7) | 33.50 | 0.83 |

| Frontal Assessment Battery (/18) | 17.8 (0.4) | 17.2 (0.9) | 20.00 | 0.16 |

Neuroimaging

Participants underwent an FDG-PET scan acquired on a Siemens Biograph 6 PET/CT scanner (Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany). After the intravenous injection of 185–370 MBq of [18F] FDG, an uptake period of 30–45 min was observed. A low-dose, non-contrast CT of the head was acquired for attenuation correction and anatomical correlation, followed by a 15-min PET acquisition in 3D mode, which was then reconstructed using ordered subset expectation maximisation with a point-spread function (Siemens HD-PET) with a 128 × 128 matrix (2.7 × 2.7 × 3.0 mm3 voxel).

All participants also underwent T1-weighted MRI on a 3T Siemens MAGNETOM Skyra (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) within 6 months of their PET-CT scan visit. Regions of interest (ROI) were defined on the co-registered T1-weighted MR image using Geodesic Information Flow (GIF), a previously described brain parcellation methodology [5, 24]. This generated eight lobar regions (frontal, temporal, parietal, occipital, insula, anterior cingulate, middle cingulate and posterior cingulate) and five subcortical regions (amygdala, hippocampus, caudate, putamen and thalamus). Frontal, temporal, parietal and occipital lobes comprised bilateral grey and white matter GIF labels whilst insula and cingulate regions comprised grey matter only. All segmentations underwent quality control: this revealed poor segmentation of caudate and putamen structures for some participants and so these were not included in standardised uptake value ratio (SUVR) or volumetric analyses (two carriers and four controls for the caudate, one carrier and three controls for the putamen).

Reconstructed PET data frames were averaged together. T1-weighted MR images were coregistered with the corresponding FDG-PET data using SPM 12 (v12.1) in Matlab R2017a and the PET images were transformed (and upsampled) into the MR space. Partial volume correction was applied to upsampled PET SUVR data using the iterative Yang method (6.8 mm kernel, 10 iterations). SUVR of the PET data was computed using the cerebellum region (as defined by the GIF parcellation). Using the MRI-defined regions of interest, SUVR values were produced for each of the lobar and subcortical regions specified above. Both scans were then transformed using NiftyReg to the MNI152 standard-space template included in FSL.

Volumetric data was expressed as a percentage of total intracranial volume (TIV), measured using SPM 12 as a combination of grey matter, white matter and cerebrospinal fluid segmentations.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed in RStudio Version 1.2.5033, GraphPad Prism Versions 8.4.3 and 9.0.0 and SPSS Version 27. Shapiro-Wilk normality tests revealed data were not normally distributed for all variables, including demographic, cognitive and imaging data, so non-parametric Mann-Whitney U tests were used to compare measures between mutation carrier and control groups. For significant group comparisons for the imaging measures, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were performed to assess the diagnostic capacity of each marker. ROC curve analyses for SUVR and volume biomarker measures combined were also performed by first performing a logistic regression model using carrier/control as the outcome variable and SUVR and volume measures as the covariates to calculate the predicted probabilities, then using the predicted probabilities as the input variable for a combined ROC curve.

Results

Demographic, cognitive and behavioural features of the sample are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in age, sex distribution, estimated years from symptom onset or years of education between groups. The mean (standard deviation) estimated years from onset was 12.5 (3.6) in the mutation carrier group with a range of 7 to 18 years. Group comparisons of cognitive and behavioural measures revealed no significant differences between the groups in the MMSE, MoCA or FAB. All mutation carriers and ten out of the twelve controls had a CDR NACC-FTLD sum of boxes (and therefore global score also) of 0. Two of the controls had a CDR NACC-FTLD sum of boxes (and therefore global score also) of 0.5.

Regional [18F] FDG uptake

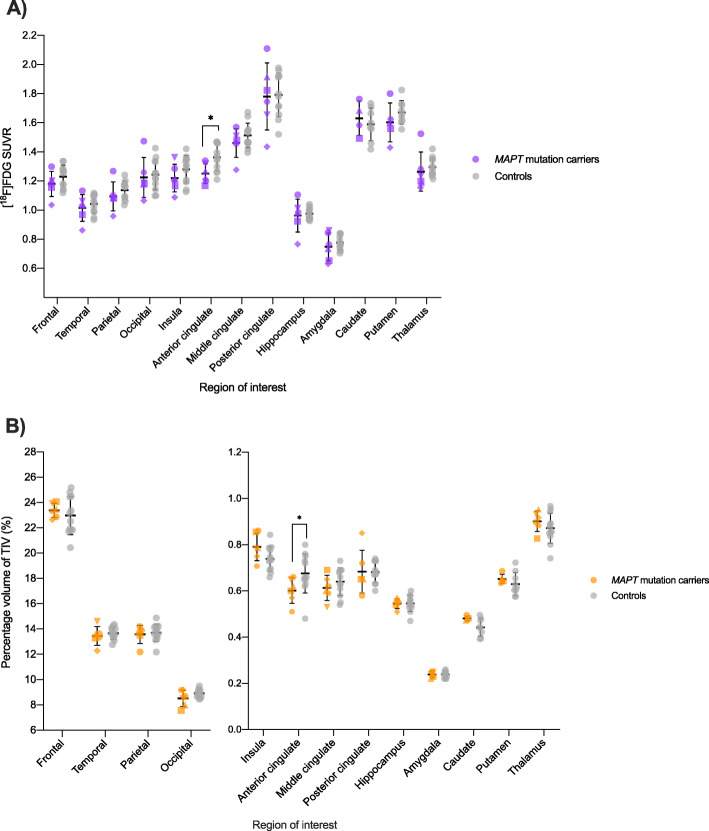

Group comparisons of regional SUVR in MAPT mutation carriers and controls revealed a significant reduction in [18F] FDG uptake in the anterior cingulate in P301L MAPT mutation carriers (mean 1.25 [standard deviation 0.07]) compared to controls (1.36 [0.09]; U = 12.00, p = 0.02) (Figs. 1 and 2a, Table 2). There were no significant differences in uptake in any other cortical or subcortical regions (Fig. 2a, Table 2). A ROC curve analysis revealed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.83 for anterior cingulate SUVR (standard error = 0.10, 95% confidence interval = 0.64 to 1.00, p = 0.03) (Supplementary Figure 1A).

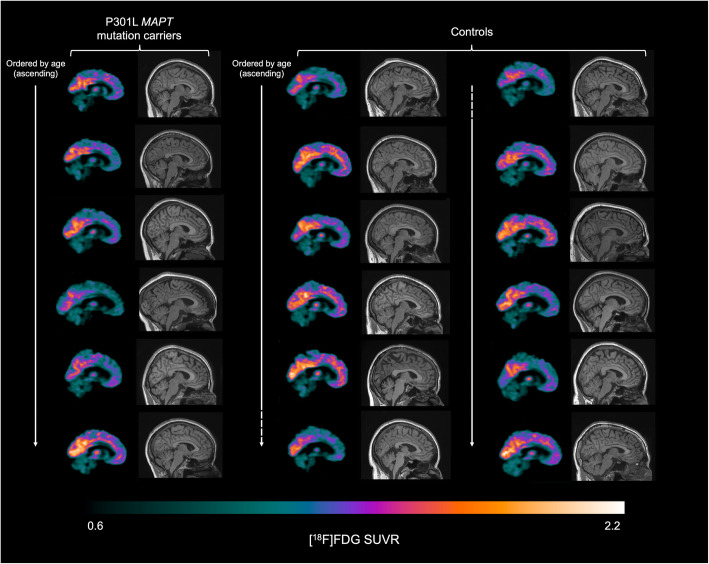

Fig. 1.

Sagittal slices illustrating the [18F] FDG SUVR in P301L MAPT mutation carriers (left column, n = 6) and controls (middle and right columns, n = 12). The same slice is presented for all participants. Slices are presented in order of ascending age

Fig. 2.

a Individual regional SUVR of [18F] FDG in MAPT mutation carriers and controls with group means and standard deviations. Purple datapoints symbolise the carrier group. b Individual regional volumes as a percentage of TIV in MAPT mutation carriers and controls with group means and standard deviations. Orange datapoints symbolise mutation carriers. Individual carriers are represented by individual shapes: circle, square, upwards-pointing triangle, downwards-pointing triangle, diamond and hexagon. Grey datapoints symbolise the control group. *p ≤ 0.05

Table 2.

Group comparisons of regional SUVR and brain volumes in P301L MAPT mutation carriers (n = 6) and controls (n = 12). Significant results in bold and italics

| Region of interest | FDG-PET imaging: regional SUVR | MR imaging: % of total intracranial volume | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation carriers, mean (SD) | Controls, mean (SD) | U | p | Mutation carriers, mean (SD) | Controls, mean (SD) | U | p | |

| Frontal | 1.18 (0.09) | 1.23 (0.08) | 27.00 | 0.44 | 23.38 (0.56) | 22.97 (1.50) | 29.00 | 0.55 |

| Temporal | 1.02 (0.09) | 1.04 (0.06) | 31.00 | 0.68 | 13.45 (0.75) | 13.66 (0.48) | 30.00 | 0.60 |

| Parietal | 1.09 (0.10) | 1.14 (0.06) | 26.00 | 0.38 | 13.57 (0.72) | 13.71 (0.68) | 35.00 | 0.96 |

| Occipital | 1.22 (0.14) | 1.24 (0.10) | 31.00 | 0.68 | 8.51 (0.64) | 8.91 (0.31) | 24.50 | 0.30 |

| Insula | 1.22 (0.09) | 1.28 (0.09) | 24.00 | 0.29 | 0.79 (0.06) | 0.74 (0.05) | 18.00 | 0.10 |

| Anterior cingulate | 1.25 (0.07) | 1.36 (0.09) | 12.00 | 0.02 | 0.60 (0.06) | 0.68 (0.08) | 14.50 | 0.04 |

| Middle cingulate | 1.46 (0.10) | 1.51 (0.08) | 30.00 | 0.62 | 0.61 (0.05) | 0.64 (0.06) | 25.50 | 0.34 |

| Posterior cingulate | 1.78 (0.23) | 1.79 (0.15) | 34.00 | 0.89 | 0.68 (0.09) | 0.68 (0.05) | 29.00 | 0.54 |

| Hippocampus | 0.96 (0.11) | 0.98 (0.04) | 35.00 | 0.96 | 0.55 (0.02) | 0.55 (0.03) | 35.00 | 0.95 |

| Amygdala | 0.75 (0.10) | 0.78 (0.05) | 32.00 | 0.75 | 0.24 (0.01) | 0.24 (0.01) | 35.00 | 0.91 |

| Caudate | 1.63 (0.12) | 1.59 (0.11) | 12.00 | 0.57 | 0.48 (0.01) | 0.44 (0.04) | 6.00 | 0.11 |

| Putamen | 1.60 (0.13) | 1.67 (0.08) | 13.00 | 0.24 | 0.65 (0.02) | 0.63 (0.05) | 14.00 | 0.30 |

| Thalamus | 1.26 (0.13) | 1.30 (0.06) | 19.00 | 0.12 | 0.90 (0.04) | 0.87 (0.06) | 26.00 | 0.38 |

Regional volume

Group comparisons of regional volumes also revealed a significant reduction in grey matter volume in the anterior cingulate in P301L MAPT mutation carriers (0.60% [0.06%]) compared to controls (0.68% [0.08%]; U = 14.50, p = 0.04) (Fig. 2b). No other group differences were identified (Fig. 2b, Table 2). A ROC curve analysis revealed an AUC of 0.80 for anterior cingulate volume (standard error = 0.11, 95% confidence interval = 0.59 to 1.00, p = 0.04) (Supplementary Figure 1B).

A ROC curve analysis for combined anterior cingulate SUVR and volume measures revealed an AUC of 0.85 (standard error = 0.09, 95% confidence interval = 0.66 to 1.00, p = 0.02) (Supplementary Figure 1C).

Discussion

The present study demonstrated reduced uptake of [18F] FDG and reduced grey matter volume in the anterior cingulate in P301L MAPT mutation carriers. The mean estimated years from symptom onset in this group was 12.5 years, with the nearest participant to onset being 7 years away, suggesting very early presymptomatic involvement of the anterior cingulate in genetic FTD caused by this mutation. Reduced uptake or brain volume was not found in any other lobar or subcortical region of interest.

Few studies have explored FDG-PET in presymptomatic FTD. A study of FDG-PET in presymptomatic GRN carriers also revealed significant reductions in uptake in the anterior cingulate but only in the right hemisphere [14], whilst a study of presymptomatic C9orf72 repeat expansion carriers showed clusters of hypometabolism in frontal, temporal and insular cortices plus subcortical regions but no changes in the anterior cingulate [7]. Two studies have revealed temporal hypometabolism in presymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers, but with different variants to this study (N279K: [2]; 10 + 3: [8]): no studies have previously explored FDG-PET in P301L MAPT mutation carriers.

Patterns of atrophy in genetic FTD measured by MRI reveal common anterior cingulate involvement in symptomatic MAPT, GRN and C9orf72 mutation carriers [6]. However, anterior cingulate change has not been widely reported presymptomatically. Atrophy of the cingulate cortex was not detected until just prior to expected symptom onset in a combined cohort of presymptomatic carriers of FTD-causing mutations [24]. In a separate analysis of MAPT mutation carriers, the earliest detected change was in the hippocampus and amygdala, followed by temporal and insular cortices. However, this group contained a mixed cohort of different MAPT mutations, with few P301L mutation carriers. One prior study has identified distinct patterns of atrophy depending on the specific MAPT mutation [31] highlighting the importance of investigating the anatomical changes in individual mutations.

P301L mutations tend to cause a more rapidly progressive disease than other MAPT mutations once symptomatic [19] and whilst the same mutation can give rise to multiple phenotypes, most symptomatic individuals exhibit behavioural disturbances and personality change [3, 12, 15, 18]. Early involvement of the anterior cingulate may explain why P301L MAPT mutation carriers typically present with symptoms of behavioural variant FTD. The cingulate cortex can be divided into functionally distinct regions including anterior, middle and posterior cingulate. Broadly, the anterior cingulate has been deemed ‘executive’ in function [29]. It is thought to modulate attention and executive functions by influencing response selection, and lesions of the anterior cingulate have produced inattention and apathy [4]. The anterior cingulate is also thought to play a critical role in social cognition via contextual integration and evaluating the behaviour of others [1, 16]. Apathy, executive dysfunction and social cognitive impairment are all core symptoms for the diagnosis of bvFTD [23, 33].

Early anterior cingulate involvement may be attributed to its unique constitution of von Economo neurons (VENs) which exhibit selective vulnerability in FTD [25]. VENs are thought to enable humans to act quickly and intuitively in social situations, and provide fast communication with the anterior insula within the salience network, a group of regions controlling social and emotional responses [26, 28]. One post-mortem study found the anterior cingulate was one of the regions most affected by tau aggregation in MAPT-associated FTD, with disproportionate tau aggregation in VENs [17]. Furthermore, a study of the salience network using resting state functional MRI reported a trend to reduced anterior cingulate connectivity in presymptomatic MAPT mutation carriers [32].

The identification of early anterior cingulate involvement via two independent measures increases the reliability of our findings in this study. Of note, partial volume correction was applied in our analyses (therefore mitigating the effect of atrophy on the resulting SUVR signal), suggesting that anterior cingulate hypometabolism cannot only be attributed to the neuronal loss seen on MRI, and that FDG-PET may provide complementary information about neuronal dysfunction in presymptomatic P301L MAPT mutation carriers. Certainly, prior investigation of FDG-PET in presymptomatic Alzheimer's disease (AD) has illustrated widespread hypometabolism in areas associated with AD pathology in the absence of widespread atrophy, suggesting neuronal dysfunction precedes neuronal loss [20]. However, in identifying parallel changes in FDG-PET and volumetric data in the anterior cingulate, it is difficult to be clear from this cross-sectional study alone whether hypometabolic change appeared before or concurrently with regional atrophy in P301L MAPT mutation carriers. Nonetheless, ROC curve analyses suggested good diagnostic ability of both anterior cingulate hypometabolism and volume in distinguishing presymptomatic P301L MAPT mutation carriers from controls, with a marginally greater AUC for the FDG-PET signal, and an even greater AUC when combining the two outcome measures, suggesting the use of both biomarkers is superior to either one individually. Future studies should focus on identifying P301L MAPT mutation carriers early on in the disease process prior to neuronal loss, when FDG-PET alone may be abnormal, with longitudinal follow-up to assess progression.

Limitations

The study is limited by the small sample size and requires replication in a larger cohort. Poor segmentation of subcortical structures required some cases to be removed from specific ROI group comparisons, an inherent limitation of automated segmentation methods.

Conclusions

In summary, this study of P301L MAPT mutation carriers shows early anterior cingulate involvement measured by both FDG-PET and MRI. Such early and specific changes may well be important in stratifying presymptomatic participants in the context of clinical trials, but future studies need to replicate these findings and understand the longitudinal changes over time in this population.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves illustrate the capacity for A) anterior cingulate SUVR of [18F] FDG, B) anterior cingulate volume expressed as a percentage of TIV and C) combined anterior cingulate SUVR and volume biomarkers to distinguish P301L MAPT mutation carriers from controls.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- FTD

Frontotemporal dementia

- MAPT

Microtubule-associated protein tau

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PET

Positron emission tomography

- FDG-PET

[18F] fluorodeoxyglucose PET

- GENFI

Genetic Frontotemporal dementia Initiative

- MMSE

Mini-Mental State Examination

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- FAB

Frontal Assessment Battery

- CDR plus NACC FTLD

CDR plus National Alzheimer Coordinating Centre Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration component

- ROI

Regions of interest

- GIF

Geodesic Information Flow

- SUVR

Standardised uptake value ratio

- TIV

Total intracranial volume

- VENs

Von Economo neurons

Authors’ contributions

MTMC analysed and interpreted the imaging data. MTMC and FSO were major contributors in writing the manuscript. JMB was the nuclear medicine specialist. MB and ET assisted with MRI analysis. DMC assisted with PET imaging analysis. JDR and RL were major contributors to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was funded by a grant from the Société Alzheimer de Québec and a CIHR operating grant (MOP137116). MTMC is supported by a studentship from Brain Research UK. FSO was supported by a scholarship from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec – Santé. MB is supported by a Fellowship award from the Alzheimer’s Society. RL is funded by La Chaire de Recherche sur les Aphasies Primaires Progressives – Fondation Famille Lemaire (https://app-ffl.ulaval.ca/). JDR is supported by an MRC Clinician Scientist Fellowship and has received funding from the NIHR Rare Disease Translational Research Collaboration. No funding organisations had a role in the design of the study nor the collection, analysis or interpretation of the data.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the CHU de Québec-Université Laval (Québec City, Canada) research ethics board (reference number: 2017-3302). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before any study-related procedures.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Mica T. M. Clarke and Frédéric St-Onge are joint first authors.

Jonathan D. Rohrer and Robert Laforce Jr are joint senior authors.

References

- 1.Apps MAJ, Rushworth MFS, Chang SWC. The anterior cingulate gyrus and social cognition: tracking the motivation of others. Neuron. 2016;90(4):692–707. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arvanitakis Z, Witte RJ, Dickson DW, Tsuboi Y, Uitti RJ, Slowinski J, et al. Clinical-pathologic study of biomarkers in FTDP-17 (PPND family with N279K tau mutation) Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007;13(4):230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borrego-Écija S, Morgado J, Palencia-Madrid L, Grau-Rivera O, Reñé R, Hernández I, et al. Frontotemporal dementia caused by the P301L mutation in the MAPT gene: clinicopathological features of 13 cases from the same geographical origin in Barcelona, Spain. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2017;44(3–4):213–221. doi: 10.1159/000480077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bush G, Luu P, Posner MI. Cognitive and emotional influences in anterior cingulate cortex. Trends Cogn Sci. 2000;4(6):215–222. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01483-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardoso MJ, Modat M, Wolz R, Melbourne A, Cash D, Rueckert D, Ourselin S. Geodesic Information Flows: spatially-variant graphs and their application to segmentation and fusion. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2015;34(9):1976–1988. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2015.2418298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cash DM, Bocchetta M, Thomas DL, Dick KM, van Swieten JC, Borroni B, et al. Patterns of gray matter atrophy in genetic frontotemporal dementia: results from the GENFI study. Neurobiol Aging. 2018;62:191–196. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Vocht J, Blommaert J, Devrome M, Radwan A, Van Weehaeghe D, De Schaepdryver M, et al. Use of multimodal imaging and clinical biomarkers in presymptomatic carriers of C9orf72 repeat expansion. JAMA Neurol. 2020:1–10 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Deters KD, Risacher SL, Farlow MR, Unverzagt FW, Kareken DA, Hutchins GD, et al. Cerebral hypometabolism and grey matter density in MAPT intron 10 +3 mutation carriers. Am J Neurodegener Dis. 2014;3(3):103–114. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dopper EGP, Chalos V, Ghariq E, den Heijer T, Hafkemeijer A, Jiskoot LC, et al. Cerebral blood flow in presymptomatic MAPT and GRN mutation carriers: a longitudinal arterial spin labeling study. NeuroImage Clin. 2016;12(016130677):460–465. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2016.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dopper EGP, Rombouts SARB, Jiskoot LC, Den Heijer T, De Graaf JRA, De Koning I, et al. Structural and functional brain connectivity in presymptomatic familial frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2014;83(2) 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000583. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Fumagalli GG, Basilico P, Arighi A, Bocchetta M, Dick KM, Cash DM, et al. Distinct patterns of brain atrophy in Genetic Frontotemporal Dementia Initiative (GENFI) cohort revealed by visual rating scales. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2018;10(1):1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13195-018-0376-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He S, Chen S, Xia MR, Sun ZK, Huang Y, Zhang JW. The role of MAPT gene in Chinese dementia patients: a P301l pedigree study and brief literature review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:1627–1633. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S155521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hutton M, Lendon CL, Rizzu P, Baker M, Froelich S, Houlden H, et al. Association of missense and 5′-splice-site mutations in tau with the inherited dementia FTDP-17. Nature. 1998;393:702–705. doi: 10.1038/31508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacova C, Hsiung GYR, Tawankanjanachot I, Dinelle K, McCormick S, Gonzalez M, et al. Anterior brain glucose hypometabolism predates dementia in progranulin mutation carriers. Neurology. 2013;81(15):1322–1331. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a8237e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kodama K, Okada S, Iseki E, Kowalska A, Tabira T, Hosoi N, et al. Familial frontotemporal dementia with a P301L tau mutation in Japan. J Neurol Sci. 2000;176(1):57–64. doi: 10.1016/S0022-510X(00)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lavin C, Melis C, Mikulan E, Gelormini C, Huepe D, Ibañez A. The anterior cingulate cortex: an integrative hub for human socially-driven interactions. Front Neurosci. 2013;7(May):1–4. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin LC, Nana AL, Hepker M, Hwang JHL, Gaus SE, Spina S, et al. Preferential tau aggregation in von Economo neurons and fork cells in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with specific MAPT variants. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2019;7(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s40478-019-0809-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Miki T, Yokota O, Takenoshita S, Mori Y, Yamazaki K, Ozaki Y, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration due to P301L tau mutation showing apathy and severe frontal atrophy but lacking other behavioral changes: a case report and literature review. Neuropathology. 2018;38(3):268–280. doi: 10.1111/neup.12441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore KM, Nicholas J, Grossman M, McMillan CT, Irwin DJ, Massimo L, et al. Age at symptom onset and death and disease duration in genetic frontotemporal dementia: an international retrospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020:145–56 10.1016/s1474-4422(19)30394-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Mosconi L, Sorbi S, De Leon MJ, Li Y, Nacmias B, Myoung PS, et al. Hypometabolism exceeds atrophy in presymptomatic early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. J Nucl Med. 2006;47(11):1778–1786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panman JL, Jiskoot LC, Bouts MJRJ, Meeter LHH, van der Ende EL, Poos JM, et al. Gray and white matter changes in presymptomatic genetic frontotemporal dementia: a longitudinal MRI study. Neurobiol Aging. 2019;76:115–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2018.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Poorkaj P, Bird TD, Wijsman E, Nemens E, Garruto RM, Anderson L, et al. Tau is a candidate gene for chromosome 17 frontotemporal dementia. Ann Neurol. 1998;43(6):815–825. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rascovsky K, Hodges JR, Knopman D, Mendez MF, Kramer JH, Neuhaus J, et al. Sensitivity of revised diagnostic criteria for the behavioural variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2011;134(9):2456–2477. doi: 10.1093/brain/awr179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rohrer JD, Nicholas JM, Cash DM, van Swieten J, Dopper E, Jiskoot L, et al. Presymptomatic cognitive and neuroanatomical changes in genetic frontotemporal dementia in the Genetic Frontotemporal dementia Initiative (GENFI) study: a cross-sectional analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(3):253–262. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70324-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seeley WW, Carlin DA, Allman JM, Macedo MN, Bush C, Miller BL, DeArmond SJ. Early frontotemporal dementia targets neurons unique to apes and humans. Ann Neurol. 2006;60(6):660–667. doi: 10.1002/ana.21055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27(9):2349–2356. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5587-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spillantini MG, Murrell JR, Goedert M, Farlow MR, Klug A, Ghetti B. Mutation in the tau gene in familial multiple system tauopathy with presenile dementia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95(13):7737–7741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stevens FL, Hurley RA, Taber KH. Anterior cingulate cortex: unique role in cognition and emotion. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;23(2):121–125. doi: 10.1176/jnp.23.2.jnp121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vogt BA, Finch DM, Olson CR. Functional heterogeneity in cingulate cortex: the anterior executive and posterior evaluative regions. Cereb Cortex. 1992;2(6):435–443. doi: 10.1093/cercor/2.6.435-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warren JD, Rohrer JD, Rossor MN. Frontotemporal dementia. BMJ. 2013;347(f4827):1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Whitwell JL, Jack CR, Boeve BF, Senjem ML, Baker M, Ivnik RJ, et al. Atrophy patterns in IVS10+16, IVS10+3, N279K, S305N, P301L, and V337M MAPT mutations. Neurology. 2009;73(13):1058–1065. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b9c8b9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitwell JL, Josephs KA, Avula R, Tosakulwong N, Weigand SD, Senjem ML, et al. Altered functional connectivity in asymptomatic MAPT subjects a comparison to bvFTD. Neurology. 2011;77(9):866–874. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822c61f2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woollacott IOC, Rohrer JD. The clinical spectrum of sporadic and familial forms of frontotemporal dementia. J Neurochem. 2016;138:6–31. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves illustrate the capacity for A) anterior cingulate SUVR of [18F] FDG, B) anterior cingulate volume expressed as a percentage of TIV and C) combined anterior cingulate SUVR and volume biomarkers to distinguish P301L MAPT mutation carriers from controls.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.