Abstract

Background

The antihypertensive angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) have similar indications and mechanisms of action, but prior work suggests divergence in their effects on cognition.

Methods

Participants in the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center database with a clinical diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) using an ACE-I or an ARB at any visit were selected. The primary outcome was delayed recall memory on the Wechsler Memory Scale Revised – Logical Memory IIA. Other cognitive domains were explored, including attention and psychomotor processing speed (Trail Making Test [TMT]-A and Digit Symbol Substitution Test [DSST]), executive function (TMT-B), and language and semantic verbal fluency (Animal Naming, Vegetable Naming, and Boston Naming Tests). Random slopes mixed-effects models with inverse probability of treatment weighting were used, yielding rate ratios (RR) or regression coefficients (B), as appropriate to the distribution of the data. Apolipoprotein (APOE) ε4 status and blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetrance were investigated as effect modifiers.

Results

Among 1689 participants with AD, ARB use (n = 578) was associated with 9.4% slower decline in delayed recall performance over a mean follow-up of 2.28 years compared with ACE-I use (n = 1111) [RR = 1.094, p = 0.0327]; specifically, users of BBB-crossing ARBs (RR = 1.25, p = 0.002), BBB-crossing ACE-Is (RR = 1.16, p = 0.010), and non-BBB-crossing ARBs (RR = 1.20, p = 0.005) had better delayed recall performance over time compared with non-BBB-crossing ACE-I users. An interaction with APOE ε4 status (drug × APOE × time RR = 1.196, p = 0.033) emerged; ARBs were associated with better delayed recall scores over time than ACE-Is in non-carriers (RR = 1.200, p = 0.003), but not in carriers (RR = 1.003, p = 0.957). ARB use was also associated with better performance over time on the TMT-A (B = 2.023 s, p = 0.0004) and the DSST (B = 0.573 symbols, p = 0.0485), and these differences were significant among APOE ε4 non-carriers (B = 4.066 s, p = 0.0004; and B = 0.982 symbols, p = 0.0230; respectively). Some differences were seen also in language and verbal fluency among APOE ε4 non-carriers.

Conclusions

Among APOE ε4 non-carriers with AD, ARB use was associated with greater preservation of memory and attention/psychomotor processing speed, particularly compared to ACE-Is that do not cross the blood-brain-barrier.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13195-021-00778-8.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, Hypertension, Angiotensin receptor blockers, Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, Cognition, Memory

Background

Hypertension currently affects roughly two thirds of all Americans aged 65 or older [1], and its burden has steadily increased in past decades [2]. In addition to being a major contributor to cardiovascular disease risk and mortality, hypertension has recently been established as a significant independent risk factor for cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) dementia [3–5]. Individuals with hypertension have been shown to exhibit poorer performance in multiple cognitive domains, including memory, psychomotor processing speed, attention, and executive function [6–8]. Consequently, the relationships between the use of antihypertensive medications with dementia incidence and cognitive decline have become an important area of research. Some evidence has shown that reductions in cerebral blood flow associated with hypertension can be reversed through antihypertensive treatment, potentially mitigating cognitive and functional decline associated with AD [9, 10]. However, the results have been variable; while the SPRINT-MIND randomized clinical trial recently associated intensive blood pressure (BP) control with a reduced risk of mild cognitive impairment or probable dementia [11], and several observational studies have associated the use of any antihypertensive agent with a reduced risk of incident dementia or cognitive decline [12–15], others have identified no significant benefits on one or both outcomes [16–18].

Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-Is) are first-line treatment options for hypertension which have similar indications and safety profiles [19]. Mechanistically, they both act upon targets within the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS) to elicit their blood pressure-lowering effects, with ARBs acting at the angiotensin II type-1 receptors (AT1Rs), and ACE-Is acting upstream at the angiotensin-converting enzyme-1 (ACE-1) [20]. Despite these similarities, a growing body of literature suggests that these antihypertensive classes may differ in their neuroprotective effects. Observational studies have found both ARBs and ACE-Is to be independently associated with reduced cognitive decline and incident dementia [21–24]; in contrast, the literature in toto has been met with mixed conclusions [12, 16], which may be due in part to heterogeneity in the study populations. Direct head-to-head comparisons of ARBs vs. ACE-Is have been limited, but studies have associated ARB use with less brain atrophy [25, 26], lower dementia incidence [23, 27–29], and slower cognitive decline [25, 30, 31] relative to ACE-I use. In a previous pathology study, ARB use was associated with fewer plaques and tangles than ACE-I use, suggesting that these agents may act differently on AD pathological development [32] and that therefore their effects might be examined specifically in the context of AD [33].

This longitudinal study aimed to compare users of ACE-Is vs. ARBs with a diagnosis of AD dementia on memory and other cognitive outcomes over time. Taking advantage of a relatively large sample size from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database [34], the study further aimed to elucidate factors that may have contributed to heterogeneity in the existing body of literature. Specifically, apolipoprotein (APOE) ε4 allele carrier status was examined due to its established role as strongest genetic risk factor for AD, in addition to previous evidence supporting associations between APOE genotype and neurological outcomes among users of ARBs or ACE-Is [35]. Furthermore, given conflicting evidence that the ability of these drugs to penetrate the blood-brain barrier (BBB) may be integral to their neurological benefits [24, 35, 36], we further compared BBB-crossing and non-BBB-crossing ARBs and ACE-Is.

Methods

Data source

The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) was established in 1999 by the National Institute on Aging/NIH (U01 AG016976) to facilitate collaborative research. The NACC database consists of longitudinal participant data from approximately 39 different U.S. Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs). This analysis reflects data from the National Alzheimer’s Clinical Coordinating Center (NACC) Uniform Data Set (UDS) collected between September 2005 and June 2019. The NACC UDS collects data in a structured and standardized format across all ADCs using a prospective, longitudinal clinical evaluation. Subjects enrolled at each ADC may come from clinician referral, self-referral by patients or family members, active recruitment, or volunteering, and are best regarded as a referral-based or volunteer case series.

Participant selection

Participants with a diagnosis of AD based on NINCDS-ADRDA criteria or NIA-AA criteria [37, 38], who met criteria for dementia and were using an ACE-I or an ARB with at least one outcome for the Wechsler Memory Scale Revised-Logical Memory Test IIA (WMS-R LM IIA)—Delayed Recall, were selected for inclusion in the analysis. Details of the participant selection process can be seen in Figure S1. Participants using both an ACE-I and an ARB simultaneously during the study period were excluded from the analysis. Furthermore, participants with a diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia, vascular dementia, Parkinson’s disease, primary progressive aphasia, a history of traumatic brain injury, cancer, or epilepsy were also excluded from the analysis.

Drug exposures

Medication use within 2 weeks of each participant visit was identified from a structured medication inventory. Participants, or co-participants where appropriate, were asked to bring to or report all prescription medications being used currently or within 2 weeks prior to each study visit. The medication inventories were then completed by trained ADC staff or physicians. ACE-Is and ARBs were the drug classes of interest. Other antihypertensive drug classes, including beta-adrenergic antagonists (BBs), calcium channel blockers (CCBs), and diuretics (DRTCs), were also identified for inclusion as covariates in the analyses.

In addition to comparing ARBs and ACE-Is overall, we performed a secondary analysis examining the role of blood-brain barrier penetrance in moderating drug effects on cognition. For this purpose, individuals were allocated to four groups according to their prescription: (1) users of non-BBB-crossing ARBs [eprosartan, irbesartan, losartan, olmesartan], (2) users of BBB-crossing ARBs [azilsartan, candesartan, telmisartan, valsartan], (3) users of non-BBB-crossing ACE-Is [benazepril, enalapril, moexepril, quinapril, ramipril], and (4) users of BBB-crossing ACE-Is [captopril, fosinopril, lisinopril, perindopril, trandolapril, zofenopril]. We utilized available data from studies which have classified and categorized these drugs previously, predominantly on the basis of evidence from basic animal science data [39–47] and existing observational analyses [30, 35, 48–50].

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of interest was delayed recall score assessed using the Wechsler Memory Scale Revised-Logical Memory Test IIA (WMS-R LM IIA) (scores range between 0 and 25; higher scores indicate better performance) [51]. Recall trials occurred after a 20-min delay. Delayed recall was selected as the primary outcome because it is a sensitive measure of memory and highly reflective of a cognitive domain impacted profoundly in those with AD [52, 53].

Exploratory outcomes

Given the broader associations between hypertension and overall cognitive decline [6–8], we examined how ARBs vs. ACE-Is might impact other domains of cognition by performing comparisons of the [1] Trail Making Test (TMT) A and B (time to completion) [54], [2] WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution Test (DSST [number of correct symbols; scores range between 0 and 93]) [55], [3] CERAD Animal Category Fluency (total score; scores range between 0 and 77) [56], [4] Vegetable Category Fluency total score (total score; scores range between 0 and 77) [56], and [5] Boston Naming Test (total score; scores range between 0 and 30) [57] in the same subset of participants who were analyzed for delayed recall outcomes. As these were exploratory analyses, we did not adjust for multiple comparisons.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were conducted using R (version 3.6.2), and figures were created using the ggplot2 package [58]. Descriptive statistics were generated to characterize the study cohort according to all study variables. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to compare the groups for continuous variables, and chi-square or Fisher exact testing was used to compare the groups for nominal or categorical variables at baseline.

To quantify the associations between ARB vs. ACE-I use and longitudinal changes in delayed recall, zero-inflated negative binomial mixed-effects regression models with random slopes and intercepts were used (glmmTMB package) [59]. For the TMT-A and TMT-B, zero-inflated Gaussian variants of this model were used to accommodate the distribution of the data, with 150 s minus time-to-completion used as the outcome for the TMT-A, and 300 s minus time-to-completion used as the outcome for the TMT-B. Zero-inflated models were used to handle potential floor or ceiling effects resulting from an excess of zeroes in the outcome scores. For the WAIS-R DSST, Animal Fluency, Vegetable Fluency, and Boston Naming Test, linear mixed-effects models with random slopes and intercepts were used. For negative binomial mixed-effects models, effect sizes were reported as rate ratios (RRs), which indicate the fold-change in delayed recall score over time relative to the reference group. For zero-inflated Gaussian mixed-effects models, unstandardized regression coefficients (B) were reported; finally, for regular linear mixed-effects models, standardized coefficients (β) were used to express the magnitude of associations. For the main analyses, ACE-Is were selected as the reference group. Correction for multiple comparisons were not applied to the various permutations of BBB-crossing and non-BBB-crossing drug comparisons, as the estimates were derived from a single model with a variable reference group. All models were adjusted for clinically important covariates, including sex, baseline MMSE score, and at each study visit, age, years of education, atrial fibrillation, beta blocker use, calcium channel blocker use, diuretic use, concomitant AD medication use, systolic BP, smoking, and depression within the preceding 2 years. Additionally, models were adjusted for potential confounding by indication, through the implementation of inverse probability of treatment weighting (IPTW) based on factors selected a priori which may have influenced the likelihood to be prescribed an ARB or an ACE-I (ipw package) [60]. Specifically, marginal structural models which consider previous drug exposure were used to generate stabilized time-varying treatment probability weights based on the following factors: race, body mass index (BMI), stroke, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, myocardial infarction, and heart failure. These factors were selected based on American hypertension management guidelines [61–63] and were ascertained using variables which existed within the UDS.

The APOE ε4 allele is a genetic risk factor for late-onset AD and accelerates disease progression [64, 65]. Therefore, as a further exploratory analysis, we investigated APOE ε4 allele carrier status (those with an ε2/ε4, ε3/ε4, or ε4/ε4 genotype) as a potential modifier of the associations between ARB or ACE-I use and cognition over time, using a drug × APOE ε4 × time interaction term. We then determined the conditional associations between drug class and cognitive outcomes over time in APOE ε4 carriers and APOE ε4 non-carriers.

Sensitivity analyses were considered to ensure the robustness of estimates. A post hoc model in which users of ARBs or ACE-Is who switched between the two drug classes during the study period were excluded was conducted in order to ascertain potential cross-over effects, although the marginal structural models used for propensity weighting account for previous exposures. Furthermore, because prescription practices may differ geographically, from site to site, a post hoc model was conducted with NACC ADC identifiers incorporated into the IPTW.

Results

Subject characteristics

Of 40,481 participants (140,861 visits conducted between September 2005 and June 2019), we identified a total of 1689 participants (3028 visits) who met criteria for inclusion with a diagnosis of AD dementia, available delayed recall outcomes, and use of an ARB or an ACE-I (participant selection process shown in Figure S1). The mean duration of follow-up did not differ significantly between users of ARBs (2.28 ± 1.48 years among the 46.5% with ≥ 2 observations, n = 578 at baseline, n = 257 BBB-crossing) and users of ACE-Is (2.27 ± 1.51 years among the 45.6% with ≥ 2 observations, n = 1111 at baseline, n = 757 BBB-crossing). Baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1. Users of ARBs and ACE-Is did not differ significantly in the prevalence of vascular risk factors, but there was a greater proportion of women and a higher MMSE score at baseline in the ARB-treated group. Additionally, a higher proportion of ARB users suffered from active depression and reported concurrent use of a CCB at baseline. These characteristics were included as covariates in all models.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and characteristics by diagnosis and medication class

| ARB (n = 578) |

ACE-I (n = 1111) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline demographics | |||

| Follow-up time (years) | 2.28 (1.48) | 2.27 (1.51) | 0.904 |

| Age (years) | 77.2 (8.1) | 76.8 (8.6) | 0.377 |

| Female (%) | 360 (62.3%) | 533 (48.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Race (Caucasian) | 468 (81.0%) | 925 (83.3%) | 0.240 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.5 (5.0) | 27.1 (5.0) | 0.128 |

| Education (years) | 14.3 (3.5) | 14.2 (3.6) | 0.577 |

| Smoking history (years) | 11.4 (16.6) | 10.6 (16.4) | 0.342 |

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | 139.0 (20.2) | 137.8 (20.4) | 0.269 |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg) | 75.6 (11.2) | 74.3 (11.0) | 0.019 |

| AD-related measures | |||

| MMSE | 22.5 (4.9) | 21.8 (5.4) | 0.004 |

| APOE ε4 carrier | 311 (53.8%) | 648 (58.3%) | 0.075 |

| AD medication use | 396 (68.5%) | 738 (66.4%) | 0.387 |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Hypercholesterolemia | 376 (65.1%) | 727 (65.6%) | 0.818 |

| Hypertension | 549 (95.0%) | 1025 (92.3%) | 0.112 |

| Stroke/TIA history | 87 (15.1%) | 148 (13.3%) | 0.330 |

| Heart failure | 29 (5.0%) | 43 (3.9%) | 0.268 |

| Myocardial infarct | 43 (7.5%) | 120 (10.8%) | 0.026 |

| Diabetes | 131 (22.7%) | 264 (23.8%) | 0.613 |

| Depression | 246 (42.6%) | 408 (36.7%) | 0.019 |

| Other medication use | |||

| β-Blockers | 140 (24.2%) | 308 (27.7%) | 0.122 |

| CCBs | 166 (28.7%) | 267 (24.0%) | 0.036 |

| DRTCs | 220 (38.1%) | 370 (33.3%) | 0.052 |

| Statins | 338 (58.5%) | 694 (62.5%) | 0.111 |

| Antidepressants | 216 (37.4%) | 407 (36.6%) | 0.766 |

| NSAIDs | 262 (45.3%) | 508 (45.7%) | 0.877 |

Continuous variables and categorical variables were reported in observed/unweighted mean (SD) and proportion, respectively

Relationships between ARB vs. ACE-I use and memory decline

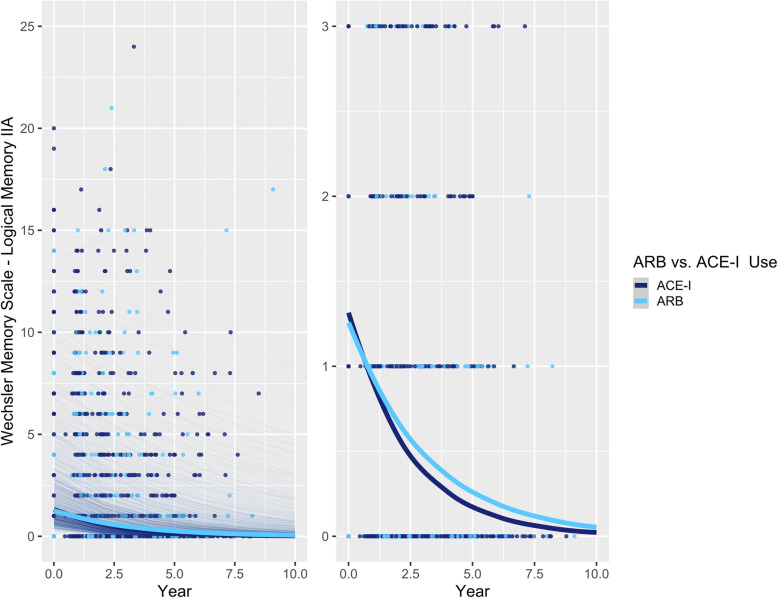

The use of an ARB was associated with a 9.4% slower decline in delayed recall compared to the use of an ACE-I (RR [95% confidence interval] = 1.094 [1.007, 1.188], p = 0.0327; Table 2; Fig. 1). In a post hoc analysis excluding individuals who switched between ARBs and ACE-Is during the study period (n = 32), the estimate remained significant (RR = 1.099 [1.008, 1.199], p = 0.0323). Moreover, including NACC ADC identifiers in the IPTW model did not significantly impact the estimate (RR = 1.096 [1.008, 1.191], p = 0.0304).

Table 2.

Rate ratios for relationships between WMS-R LM IIA—Delayed Recall score and ACE-I vs. ARB use over time (n = 1689)

| Overall | APOE ε4 non-carriers | APOE ε4 carriers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR [95% CI] | z | p value | RR [95% CI] | z | p value | RR [95% CI] | z | p value | |

| ARBs vs. ACE-Is | 1.094 [1.007, 1.188] | 2.14 | 0.0327 | 1.200 [1.064, 1.354] | 2.97 | 0.0030 | 1.003 [0.897, 1.122] | 0.06 | 0.9568 |

| C-ARBs vs. NC-ACE-Is | 1.250 [1.089, 1.434] | 3.16 | 0.0015 | 1.354 [1.116, 1.642] | 3.08 | 0.0020 | 1.130 [0.932, 1.371] | 1.25 | 0.2124 |

| C-ACE-Is vs. NC-ACE-Is | 1.158 [1.036, 1.293] | 2.57 | 0.0098 | 1.168 [0.995, 1.385] | 1.90 | 0.0571 | 1.140 [0.976, 1.331] | 1.65 | 0.0993 |

| NC-ARBs vs. NC-ACE-Is | 1.199 [1.055, 1.365] | 2.79 | 0.0054 | 1.324 [1.108, 1.583] | 3.07 | 0.0021 | 1.104 [0.923, 1.321] | 1.08 | 0.2785 |

| C-ARBs vs. NC-ARBs | 1.042 [0.921, 1.179] | 0.65 | 0.5175 | 1.022 [0.865, 1.208] | 0.26 | 0.7947 | 1.024 [0.869, 1.205] | 0.28 | 0.7802 |

| C-ARBs vs. C-ACE-Is | 1.080 [0.965, 1.209] | 1.34 | 0.1798 | 1.159 [0.985, 1.364] | 1.78 | 0.0746 | 0.992 [0.854, 1.152] | − 0.11 | 0.9161 |

Three-way APOE × ARB vs. ACE-I × Time interaction: RR = 1.196 [1.015, 1.410], z = 2.135, p = 0.0328

C-ARB: BBB-crossing ARB; C-ACE-I: BBB-crossing ACE-I; NC-ARB: Non-BBB-crossing ARB; NC-ACE-I: Non-BBB-crossing ACE-I

Fig. 1.

Associations between ARB vs. ACE-I use and delayed recall performance over time in participants with AD. Left: plot showing full range of outcome scores; Right: plot with reduced y-axis cut-off, to better show differences between ARB and ACE-I groups. Thick lines represent the total estimated association adjusted for covariates; thin lines represent estimated associations adjusted for covariates for each participant

Relationships between ARB vs. ACE-I use and decline in performance in exploratory cognitive domains

Use of an ARB was associated with better performance on the TMT-A (B [95% confidence interval] = 2.023 [0.492, 3.553] seconds, p = 0.0096) (Table 3) and the WAIS-R DSST (β = 0.050 [0.001, 0.099], p = 0.0483, translating to 0.573 symbols) (Table 4).

Table 3.

Relationships between Trail Making Test A performance and ACE-I vs. ARB use over time (n = 1601)

| Overall | APOE ε4 non-carriers | APOE ε4 carriers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B [95% CI] | z | p value | B [95% CI] | z | p value | B [95% CI] | z | p value | |

| ARBs vs. ACE-Is | 2.023 [0.492, 3.553] | 2.59 | 0.0096 | 4.066 [1.816, 6.317] | 3.54 | 0.0004 | 1.458 [− 0.365, 3.282] | 1.57 | 0.1171 |

| C-ARBs vs. NC-ACE-Is | 3.349 [0.766. 5.933] | 2.54 | 0.0110 | 6.086 [2.431, 9.741] | 3.26 | 0.0011 | 2.054 [− 1.123, 5.230] | 1.35 | 0.1785 |

| C-ACE-Is vs. NC-ACE-Is | 0.985 [− 0.121, 3.184] | 0.88 | 0.3798 | 1.604 [− 1.061, 4.810] | 0.98 | 0.3267 | 0.771 [− 1.892, 3.434] | 0.57 | 0.5703 |

| NC-ARBs vs. NC-ACE-Is | 2.316 [− 0.176, 4.810] | 1.82 | 0.0685 | 4.480 [0.844, 8.116] | 2.42 | 0.0157 | 2.049 [− 0.936, 5.034] | 1.27 | 0.2051 |

| C-ARBs vs. NC-ARBs | 1.033 [− 1.228, 3.293] | 0.90 | 0.3705 | 1.606 [− 1.510, 4.722] | 1.01 | 0.3125 | 0.005 [− 2.598, 2.608] | 0.01 | 0.9971 |

| C-ARBs vs. C-ACE-Is | 2.364 [0.308, 4.420] | 2.25 | 0.0242 | 4.482 [1.620, 7.343] | 3.07 | 0.0022 | 1.283 [− 1.172, 3.737] | 1.02 | 0.3058 |

Three-way APOE × ARB vs. ACE-I × Time interaction: B = 2.608 [− 0.300, 5.516] s, z = 1.76, p = 0.0788

C-ARB: BBB-crossing ARB; C-ACE-I: BBB-crossing ACE-I; NC-ARB: Non-BBB-crossing ARB; NC-ACE-I: Non-BBB-crossing ACE-I

Table 4.

Relationships between WAIS-R Digit Symbol Substitution Test performance and ACE-I vs. ARB use over time (n = 1544)

| Overall | APOE ε4 non-carriers | APOE ε4 carriers | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β [95% CI] | t | df | p value | β [95% CI] | t | df | p value | β [95% CI] | t | df | p value | |

| ARBs vs. ACE-Is | 0.050[0.001, 0.099] | 1.98 | 533.5 | 0.0483 | 0.085[0.012, 0.158] | 2.28 | 533.9 | 0.0230 | 0.0471[− 0.012, 0.106] | 1.56 | 558.9 | 0.1186 |

| C-ARBs vs. NC-ACE-Is | 0.044[− 0.012, 0.101] | 1.54 | 586.1 | 0.1252 | 0.106[0.026, 0.185] | 2.60 | 647.9 | 0.0095 | 0.020 [− 0.051, 0.091] | 0.55 | 574.0 | 0.5852 |

| C-ACE-Is vs. NC-ACE-Is | 0.012[− 0.061, 0.086] | 0.33 | 562.0 | 0.7388 | 0.055[− 0.050, 0.161] | 1.03 | 708.9 | 0.3035 | − 0.023[− 0.115, 0.069] | − 0.49 | 487.1 | 0.6224 |

| NC-ARBs vs. NC-ACE-Is | 0.043[− 0.016, 0.102] | 1.42 | 600.3 | 0.1560 | 0.074[− 0.009, 0.158] | 1.74 | 694.8 | 0.0816 | 0.024[− 0.049, 0.098] | 0.65 | 523.3 | 0.5177 |

| C-ARBs vs. NC-ARBs | 0.005[− 0.046, 0.055] | 0.18 | 609.9 | 0.8567 | 0.037[− 0.030, 0.104] | 1.08 | 994.6 | 0.2822 | − 0.003[− 0.062, 0.056] | − 0.09 | 851.0 | 0.9292 |

| C-ARBs vs. C-ACE-Is | 0.036[− 0.010, 0.082] | 1.53 | 853.1 | 0.1250 | 0.070[0.003, 0.136] | 2.06 | 606.4 | 0.0400 | 0.035[− 0.020, 0.090] | 1.24 | 678.5 | 0.2147 |

Three-way APOE × ARB vs. ACE-I × Time interaction: β = 0.025 [− 0.037, 0.088], t = 0.79, p = 0.4309

C-ARB: BBB-crossing ARB; C-ACE-I: BBB-crossing ACE-I; NC-ARB: Non-BBB-crossing ARB; NC-ACE-I: Non-BBB-crossing ACE-I

There were no differences between ARBs and ACE-Is in executive function (TMT-B; Table S1), nor in language (Animal Naming, Vegetable Naming, and Boston Naming tests; Tables S2, S3, S4).

Interactions between ARB vs. ACE-Is and APOE ε4 carrier status on memory

We further examined relationships between ARB and ACE-I use separately within subgroups of APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers. With respect to delayed recall, a significant 3-way interaction emerged between ARB vs. ACE-I x Time and APOE ε4 genotype (RR = 1.196 [1.015, 1.410], p = 0.0328), such that a greater benefit of ARBs relative to ACE-Is was observed among APOE ε4 non-carriers (RR = 1.200 [1.064, 1.354], p = 0.0030) (Figure S2) than among APOE ε4 carriers (RR = 1.003 [0.897, 1.122], p = 0.9568) (Figure S2).

Interactions between ARB vs. ACE-Is and APOE ε4 carrier status on exploratory cognitive outcomes

The use of an ARB vs. an ACE-I was associated with better performance over time on the TMT-A (B = 4.066 [1.816, 6.317] seconds, p = 0.0004; Table 3) and the WAIS-R DSST (β = 0.085 [0.012, 0.158], p = 0.0230, translating to 0.982 symbols; Table 4) specifically among APOE ε4 non-carriers. The use of an ARB vs. an ACE-I was not associated with greater performance over time on the Animal Naming, Vegetable Naming, or Boston Naming tests, although significant differences were seen for some subgroup comparisons specifically within the APOE ε4 non-carriers (Tables S2, S3, S4).

BBB-crossing vs. non-BBB-crossing ARBs and ACE-Is and memory

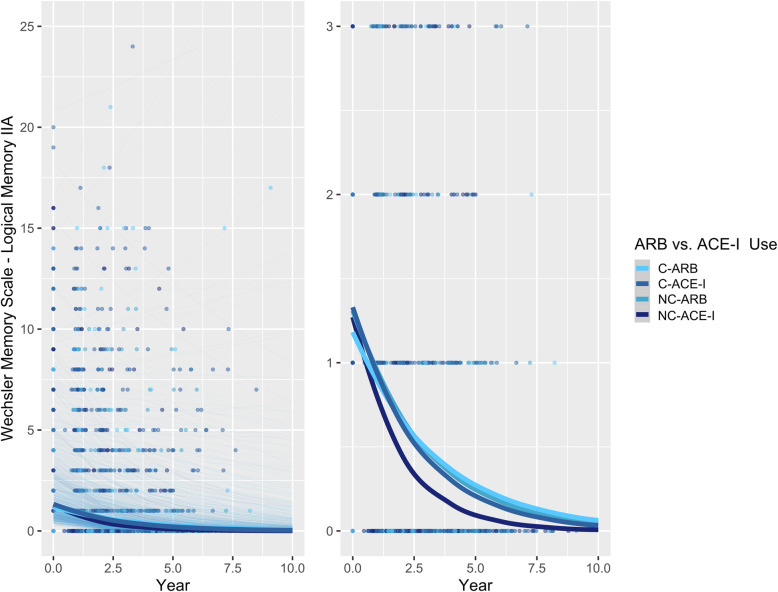

A multilevel analysis was implemented to compare BBB-crossing ARBs and ACE-Is. With respect to delayed recall, among all participants with AD, BBB-crossing ARBs (RR = 1.250 [1.089, 1.434], p = 0.0015), non-BBB-crossing ARBs (RR = 1.199 [1.055, 1.365], p = 0.0054), and BBB-crossing ACE-Is (RR = 1.158 [1.036, 1.293], p = 0.0098) were all associated with significantly better performance over time relative to non-BBB-crossing ACE-Is (Table 2; Fig. 2). However, BBB-crossing ARBs did not differ significantly from BBB-crossing ACE-Is (RR = 1.080 [0.965, 1.209], p = 0.1798).

Fig. 2.

Associations between BBB-crossing and non-BBB-crossing ARBs vs. ACE-Is and delayed recall performance over time in participants with AD. Left: plot showing full range of outcome scores. Right: plot with reduced y-axis cut-off, to better show differences between ARB and ACE-I groups. Thick lines represent the total estimated association adjusted for covariates; thin lines represent estimated associations adjusted for covariates for each participant. C-ARB: BBB-crossing ARB; C-ACE-I: BBB-crossing ACE-I; NC-ARB: Non-BBB-crossing ARB; NC-ACE-I: Non-BBB-crossing ACE-I

BBB-crossing vs. non-BBB-crossing ARBs and ACE-Is and memory in APOE ε4 carriers vs. non-carriers

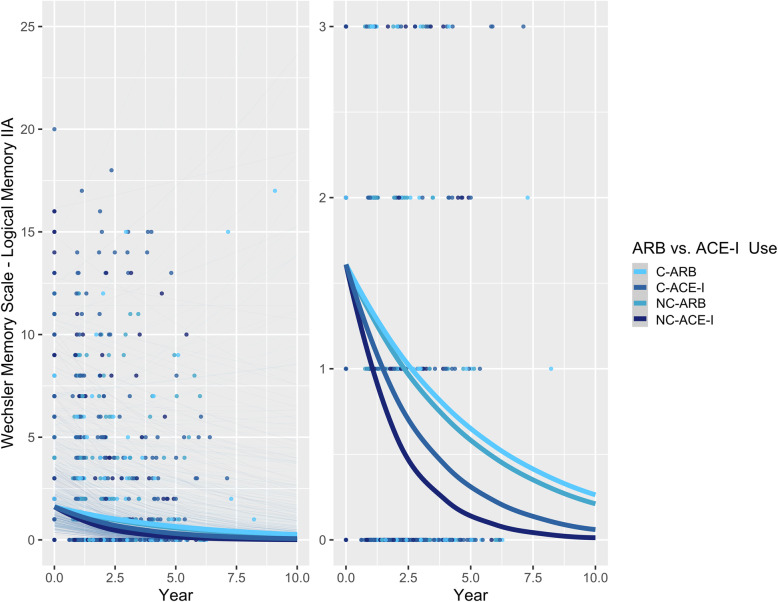

In APOE ε4 non-carriers, both BBB-crossing ARBs (RR = 1.354 [1.116, 1.642], p = 0.0020) and non-BBB-crossing ARBs (RR = 1.324 [1.108, 1.583], p = 0.0021) were associated with significantly better memory performance relative to non-BBB-crossing ACE-Is (Table 2; Fig. 3). The BBB-crossing ACE-Is did not differ significantly from the other ARBs or ACE-Is (p > 0.05; Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Associations between ARB vs. ACE-I use and delayed recall performance over time in non-APOE ε4 carriers with AD. Left: plot showing full range of outcome scores. Right: plot with reduced y-axis cut-off, to better show differences between ARB and ACE-I groups. Thick lines represent the total estimated association adjusted for covariates; thin lines represent estimated associations adjusted for covariates for each participant. C-ARB: BBB-crossing ARB; C-ACE-I: BBB-crossing ACE-I; NC-ARB: Non-BBB-crossing ARB; NC-ACE-I: Non-BBB-crossing ACE-I

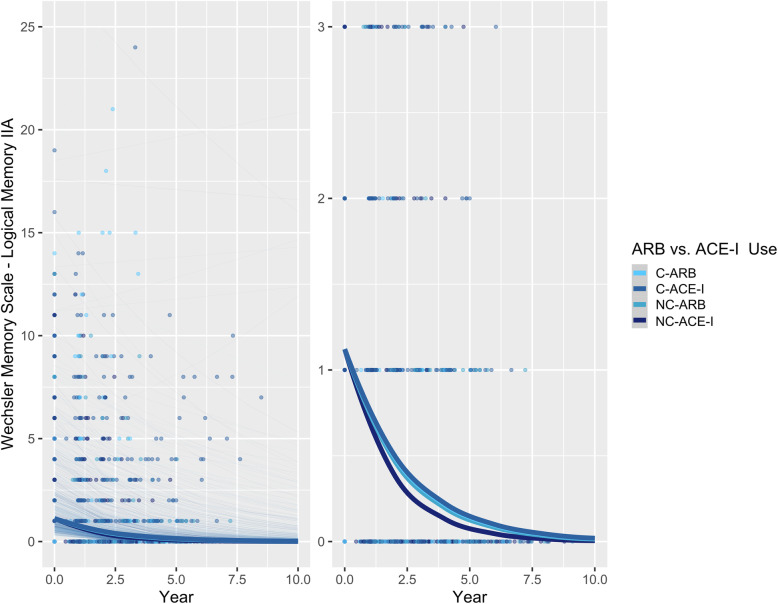

In contrast to the APOE ε4 non-carriers, there were no significant differences in memory between BBB-crossing and non-crossing ARBs and ACE-Is in APOE ε4 carriers, although non-BBB-crossing ACE-Is were still associated with the poorest performance (Table 2; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Associations between ARB vs. ACE-I use and delayed recall performance over time in APOE ε4 carriers with AD. Left: plot showing full range of outcome scores. Right: plot with reduced y-axis cut-off, to better show differences between ARB and ACE-I groups. Thick lines represent the total estimated association adjusted for covariates; thin lines represent estimated associations adjusted for covariates for each participant. C-ARB: BBB-crossing ARB; C-ACE-I: BBB-crossing ACE-I; NC-ARB: Non-BBB-crossing ARB; NC-ACE-I: Non-BBB-crossing ACE-I

BBB-crossing vs. non-BBB-crossing ARBs and ACE-Is and exploratory cognitive outcomes in APOE ε4 carriers vs. non-carriers

Similar to memory, APOE ε4 carrier status impacted the effects of ARBs vs. ACE-Is on attention, processing speed, and semantic fluency over time. No significant differences were observed in any ARB vs. ACE-I comparison among APOE ε4 carriers. In contrast, among APOE ε4 non-carriers, multiple comparisons were significant. BBB-crossing ARBs were associated with the greatest performance over time relative to non-BBB-crossing ACE-Is on the TMT-A (B = 6.086 [2.431, 9.741] seconds, p = 0.0011), DSST (β = 0.106 [0.026, 0.185], p = 0.0095), animal (β = 0.099 [0.018, 0.179], p = 0.0163), and vegetable (β = 0.128 [0.051, 0.206], p = 0.0013), naming tests (Tables 2, 3, S2, S3, S4). Additionally, BBB-crossing ARBs were associated with significantly better performance than BBB-crossing ACE-Is on the TMT-A, DSST, and vegetable naming tests (Tables 2, 3, S3).

Discussion

Exposure to an ARB was associated with better performance on tests of memory and processing speed apparent over several years of follow-up when compared with exposure to an ACE-I in older adults with a diagnosis of AD dementia. In stratified analyses, this relative benefit was found to be significant only in non-carriers of the APOE ε4 allele. The relative benefits of ARBs to ACE-Is on memory performance were not dependent on intrinsic BBB-crossing properties of ARBs but were dependent on BBB penetrance for ACE-Is, such that the use of non-BBB-crossing ACE-Is was associated with significantly poorer outcomes. This study, incorporating epidemiological techniques to specifically compare two classes of RAAS-acting antihypertensive agents, demonstrates how these two heterogeneity factors underlie differences in the cognitive effects of ARBs and ACE-Is.

The main analyses revealed that ARB use was associated with better memory performance over time compared to ACE-I use, confirming results from several previous studies [25, 32, 36, 48] although other studies have reported the opposite or a null conclusion [49, 50]. Two recently published meta-analyses examined associations between antihypertensive drugs, cognitive decline, and dementia incidence, failing to identify significant differences between drug classes [12, 16]. Findings from stratified analyses suggest some possible reasons for these discrepancies, including factors related to the populations studied, and the drugs used.

Stratification by APOE ε4 carrier status revealed that the differences between ACE-Is and ARBs were driven by the subgroup of non-carriers of the ε4 allele. These results in people with AD dementia agree with a recent analysis by Tully et al., who examined associations between antihypertensive drug use and cognitive decline in non-demented older adults [35]. In that study, RAAS-targeting agents were associated with improved cognition relative to other antihypertensive drugs. Furthermore, those authors found that exposure to an ARB, but not to an ACE-I, was associated with better performance on a test of semantic verbal fluency and speed among APOE ε4 non-carriers. They found the opposite association among APOE ε4 carriers, whereby exposure to an ACE-I, but not to an ARB, was associated with better performance. Those findings are consistent with the present findings in AD patients that ARBs were associated with significantly better cognitive performance over time specifically in APOE ε4 non-carriers.

The present study identified associations between ARB use and performance on tests of memory, attention, verbal fluency and psychomotor processing speed in people with AD dementia. In contrast, Tully et al. found no significant differences between ARBs and ACE-Is in memory or attention in older adults without dementia. Therefore, it is possible that these differences are specific to people with clinical symptoms of AD pathology. The magnitude of anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative benefits associated with ARBs through inverse agonism at the AT1R [66, 67] and upregulation of AT2R and AT4R activity [68, 69] might be amplified in AD. Furthermore, studies in vitro and in vivo have demonstrated that ARBs can increase degradation and clearance of Aβ peptides [70–72], though others in mouse models have observed no differences [73]. Moreover, a neuropathology study found that ARBs were associated with reduced Aβ plaque load, and a cross-sectional PET study yielded similar results with PiB binding [32, 33]. It has been suggested that preservation of angiotensin-converting enzyme-1 (ACE-1) function by ARBs, but not ACE-Is, may explain this difference, as ACE-1 has demonstrated a role in the prevention of Aβ aggregation and fibril formation in vitro [74, 75], although results from animal models have been highly variable [76–80].

The mechanistic reasons for the findings among ε4 non-carriers, but not among carriers, have yet to be explored. A recent study by Burnham et al. showed that APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers did not differ in their rates of Aβ accumulation once a certain threshold had been reached, but that APOE ε4 carriers arrived at that threshold, on average, 15 years earlier than non-carriers [81]. In the current analysis, the mean age of APOE ε4 non-carriers was significantly greater than APOE ε4 carriers (78.4 years vs. 75.8 years). Thus, the ε4 carriers in our analysis were likely at a more advanced stage of amyloid, tau, or AD progression in general, at which point the preservation of ACE-1 function, upregulation of ACE-2 function, or other purported anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidative, and anti-amyloidogenic mechanisms related to ARB use may lack benefit. Previous evidence has associated treatment of hypertension, regardless of antihypertensive agent, with an exponential decrease in incident AD dementia risk and cognitive decline particularly among hypertensive APOE ε4 carriers, but not non-carriers [82, 83] which might suggest that the magnitude of cognitive benefit among ε4 carriers afforded by general blood pressure-lowering effects is larger and that the importance of other mechanistic differences between ARBs and ACE-Is may be reduced relative to those observed in ε4 non-carriers. Notably, however, systolic BP was included as a time-varying covariate in all models, so the effects reported are independent of blood pressure-lowering effectiveness, which itself (i.e., systolic blood pressure over time) was not found to be a significant predictor of cognitive decline. Genetics may also play a role in explaining the heterogeneity of observed effects, as one study found that APOE ε4 carriers with specific ACE genotypes benefitted more from ACE-Is in reducing cognitive decline than did non-carriers [84]; another study suggested that APOE and ACE genotypes may interact to confer risk of AD [85]. As APOE ε4 carriers are likely to have more severe AD pathology, our results might suggest that the benefits of ARBs in APOE ε4 non-carriers could relate to effects on the cerebrovasculature that are less important in carriers. Recently, ARB use was associated with a reduced rate of amyloid accumulation in the cortex relative to ACE-I use, and this effect was also smaller in APOE ε4 carriers [86], which would be consistent, for example, with the possibility of a more profound and relevant deficit in vascular amyloid clearance with vascular brain aging as a contributing cause of amyloidosis among APOE ε4 non-carriers who were older in this sample [87]. Further work to understand disease heterogeneity is warranted. Future studies should explore ACE polymorphisms as additional heterogeneity factors, particularly to determine if ACE polymorphisms might interact with drug exposures among APOE ε4 carriers [85, 88].

Generally, BBB penetration was associated with preserved cognitive performance; however, this effect was more prominent for ACE-Is than ARBs. In most cognitive domains assessed, use of a non-crossing ACE-I was associated with the poorest performance. Previous findings around BBB penetrance have been equivocal. Consistent with our findings, Ho et al. reported better memory performance in users of BBB-crossing RAAS medications, and specifically among users of BBB-crossing ARBs relative to users of non-BBB-crossing RAAS medications [30]. Tully et al. identified no significant associations between cognition and BBB penetration for either ACE-Is or ARBs, although marginally better scores were observed among users of centrally acting ARBs, consistent with the present study [35]. For ACE-Is, previous work has associated the use of BBB-penetrating ACE-Is with reduced cognitive decline and dementia incidence relative to the use of non-BBB-crossing ACE-Is and to other antihypertensive drugs, both in an AD [50, 89] and in a non-demented population [49]. Our observations provide a context for those findings. The importance of BBB penetration in determining ACE-I effects on cognition is further supported by previous work in animal models which showed that administration of perindopril, a BBB-crossing ACE-I, increased acetylcholine levels in the brain, while non-BBB-crossing ACE-Is did not [90]. The loss of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain is a defining characteristic of AD, and thus, this mechanism could underlie some of the cognitive benefits observed.

Our observation that there was no significant difference between BBB-crossing and non-crossing ARBs on memory and other cognitive domains might be explained by several factors. In a large epidemiological analysis of 819,941 older adults by Li et al. [48], the BBB-crossing ARBs candesartan and telmisartan were associated with significant dose-dependent reductions in dementia incidence; however, valsartan was not. An important limitation of our work is that a binary classification of ARBs and ACE-Is as BBB-crossing was made although these properties likely exist on a spectrum. Additionally, we acknowledge that there were some inconsistencies between the studies used to inform our classifications, and furthermore that data from animal models might not directly translate to the Alzheimer’s disease population considered in the present analysis. For example, one study found that losartan crosses the BBB [91], while another did not [92]. Although an absolute classification can be difficult to make, relative lipophilicity can be determined with greater certainty, for example, telmisartan was found at 10-fold higher concentrations than losartan in a rodent study [93]. Although telmisartan, candesartan, and valsartan are all considered to be BBB-crossing, many studies have suggested that telmisartan and candesartan specifically may offer disproportionate neuroprotective benefits via several potential mechanisms. Sequential studies of ARBs administered peripherally in rats to counter centrally administered angiotensin II identified these two agents as being the most brain-penetrating of all ARBs [39–41], and evidence from humans and non-human primates reinforces the BBB-crossing properties of telmisartan [94–96]. Valsartan is more commonly prescribed and constituted the majority of the BBB-crossing ARBs in our analyses; therefore, sample size precluded subgroup analyses of more highly lipophilic ARBs (i.e., telmisartan and candesartan). The present findings generally support the idea that BBB penetration, coupled with other drug-specific properties, might predict neuroprotective properties of ARBs, in addition to ACE-Is. Notably, there were no differences between crossing and non-crossing agents among ε4 carriers, although trends in the same direction remained. While there are multiple possible reasons for this, APOE ε4 has been associated with breakdown and increased permeability of the BBB [97], so it is possible that any additional benefits conferred by ARBs or ACE-Is that depend on their brain-penetrating properties are nullified in this group.

Limitations

Strengths of the present work include a relatively large sample size, adjustment for confounding by indication through inverse probability of treatment weighting, and the selection of a homogeneous group of participants with AD dementia. We also acknowledge several limitations. Diagnoses were based primarily upon clinical criteria rather than biomarker and imaging data. Analyses could not be adjusted for drug dosage and drug adherence, because this information was not available in the NACC database. This might be important given evidence from Li et al. which suggested a dose-dependent effect of ARBs whereby higher doses were associated with lower dementia incidence [98]. Duration of drug exposure prior to entry into the NACC cohort was not available. Similarly, duration of hypertension and other vascular comorbidities (e.g. diabetes, hypercholesterolemia) were not available. Partially due to phasing out of the WMS-R LM IIA between UDS 2.0 and UDS 3.0, there was a high rate of loss to follow-up, such that fewer than half of all participants included in the analyses had more than one observation for the outcome of delayed recall; however, loss to follow-up was similar between exposure groups. It should be acknowledged that sampling bias might limit generalizability as participants enrolling into ADC cohorts typically have a higher level of education and socioeconomic status than the general population. Although we implemented inverse probability of treatment weighting to address potential confounding by indication, chronic kidney disease is a factor that may influence the prescription of ACE-Is vs. ARBs, but data on this diagnosis were not available. The findings do not provide mechanistic insight; further studies might examine biomarker data, including Aβ and tau, in addition to expression of RAAS components, such as ACE-1, ACE-2, and Mas, AT2R, AT4R, and other receptors in the regulatory arm of the pathway.

Conclusion

This longitudinal analysis of participants with a diagnosis of AD dementia revealed that ARB exposure was associated with favorable cognitive outcomes relative to ACE-I exposure. This relationship was found to be heavily dependent on APOE genotype with ARBs yielding greatest benefits in APOE ε4 allele non-carriers. BBB penetration was identified as a significant moderator of the effects of ACE-Is, but not ARBs. The results consolidate previous findings. Further prospective studies should investigate the mechanisms by which ARBs may exert neuroprotective properties that may be beneficial against AD, in addition to how patient-level (e.g. genomic) factors might contribute to heterogeneity in drug response. Intervention trials to determine if ARBs may be preferable in patients with clinical symptoms of cognitive decline might also consider this opportunity for pharmacogenetics to optimize trial design and ultimately, prescription patterns.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Participant inclusion/exclusion flowchart, APOE ε4 carrier vs. non-carrier plots, and tables for secondary cognitive outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by the NIA-funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P30 AG062428-01 (PI James Leverenz, MD) P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P30 AG062421-01 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P30 AG062422-01 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Thomas Wisniewski, MD), P30 AG013854 (PI Robert Vassar, PhD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P30 AG062429-01(PI James Brewer, MD, PhD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG053760 (PI Henry Paulson, MD, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P30 AG049638 (PI Suzanne Craft, PhD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Grabowski, MD), P30 AG062715-01 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

Abbreviations

- Aβ

Amyloid beta

- AD

Alzheimer’s disease

- ARB

Angiotensin II type-1 receptor blocker

- ATxR

Angiotensin II type “X” Receptor

- ACE-I

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor

- APOE

Apolipoprotein E

- BBB

Blood-brain barrier

- NACC

National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Centre

- RR

Rate ratio

- RAAS

Renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system

- TMT-A

Trail Making Test A

- TMT-B

Trail Making Test B

Authors’ contributions

MO: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, visualization, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. CW: formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, validation, writing—review and editing. JSR: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, writing—review and editing. AJ: writing—review and editing. JDE: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, writing—review and editing. JR: writing—review and editing. MM: writing—review and editing. RHS: writing—review and editing. NH: conceptualization, writing—review and editing. KLL: conceptualization, writing—review and editing. SEB: conceptualization, funding acquisition, supervision, writing—review and editing. WS: conceptualization, investigation, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation [20141208], the Weston Brain Institute [20121211], the Alzheimer’s Association (USA), Brain Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (PJT-159711), the Michael J. Fox Foundation, Alzheimer’s Research UK, the Heart and Stroke Foundation Canadian Partnership for Stroke Recovery, the LC Campbell Cognitive Neurology Unit, and the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Department of Psychiatry. The funders were not involved at any stage of the study.

Availability of data and materials

The data analyzed in the current study were obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC). For further information on access to the database, please contact NACC (contact details can be found at https://www.alz.washington.edu/).

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As determined by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division, the NACC database itself is exempt from IRB review and approval because it does not involve human participants, as defined by federal and state regulations. However, all contributing ADCs are required to obtain informed consent from their participants and maintain their own separate IRB review and approval from their institution prior to submitting data to NACC.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MO, CW, JSR, AJ, JDE, JR, MM, RHS, NH, KLL, SEB, and WS report no potential competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Nwankwo T, Yoon SSU, Burt V, Gu Q. Hypertension among adults in the United States: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011–2012. NCHS Data Brief. 2013;133:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorans SK, Mills KT, Liu Y, He J. Trends in prevalence and control of hypertension according to the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Guideline. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;7(11):e008888. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.008888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skoog I, Nilsson L, Persson G, Lernfelt B, Landahl S, Palmertz B, et al. 15-year longitudinal study of blood pressure and dementia. Lancet. 1996;347(9009):1141–1145. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90608-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perrotta M, Lembo G, Carnevale D. Hypertension and dementia: epidemiological and experimental evidence revealing a detrimental relationship. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(3):347. doi: 10.3390/ijms17030347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kennelly SP, Lawlor BA, Kenny RA. Blood pressure and dementia - a comprehensive review. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2009;2(4):241–260. doi: 10.1177/1756285609103483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iadecola C, Yaffe K, Biller J, Bratzke LC, Faraci FM, Gorelick PB, et al. Impact of hypertension on cognitive function: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Hypertens (Dallas, Tex 1979) 2016;68(6):e67–e94. doi: 10.1161/HYP.0000000000000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Saxby BK, Harrington F, McKeith IG, Wesnes K, Ford GA. Effects of hypertension on attention, memory, and executive function in older adults. Vol. 22, Health Psychology. Ford, Gary A.: Wolfson Unit of Clinical Pharmacology, University of Newcastle upon Tyne, Claremont Place, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom, NE2 4HH, g.a.ford@ncl.ac.uk: American Psychological Association; 2003. p. 587–91. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Gąsecki D, Kwarciany M, Nyka W, Narkiewicz K. Hypertension, brain damage and cognitive decline. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2013;15(6):547–558. doi: 10.1007/s11906-013-0398-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wiesmann M, Roelofs M, van der Lugt R, Heerschap A, Kiliaan AJ, Claassen JAHR. Angiotensin II, hypertension and angiotensin II receptor antagonism: roles in the behavioural and brain pathology of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;37(7):2396–2413. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16667364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Jong DLK, de Heus RAA, Rijpma A, Donders R, Olde Rikkert MGM, Günther M, et al. Effects of nilvadipine on cerebral blood flow in patients with Alzheimer disease. Hypertension. 2019;74(2):413–420. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.12892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.SPRINT MIND Investigators for the SPRINT Research Group. Williamson JD, Pajewski NM, Auchus AP, Bryan RN, Chelune G, et al. Effect of intensive vs standard blood pressure control on probable dementia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2019;321(6):553–561. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.21442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding J, Davis-Plourde KL, Sedaghat S, Tully PJ, Wang W, Phillips C, et al. Antihypertensive medications and risk for incident dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis of individual participant data from prospective cohort studies. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(1):61–70. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30393-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duron E, Rigaud A-S, Dubail D, Mehrabian S, Latour F, Seux M-L, et al. Effects of antihypertensive therapy on cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Hypertens. 2009;22(9):1020–1024. doi: 10.1038/ajh.2009.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. Lancet. 2017;390(10113):2673–2734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yasar S, Xia J, Yao W, Furberg CD, Xue Q-L, Mercado CI, et al. Antihypertensive drugs decrease risk of Alzheimer disease: Ginkgo Evaluation of Memory Study. Neurology. 2013;81(10):896–903. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a35228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters R, Yasar S, Anderson CS, Andrews S, Antikainen R, Arima H, et al. Investigation of antihypertensive class, dementia, and cognitive decline. Neurology. 2020;94(3):e267 LP–e26e281. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelber RP, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Masaki KH, Launer LJ, White LR. Antihypertensive medication use and risk of cognitive impairment: the Honolulu-Asia Aging Study. Neurology. 2013;81(10):888–895. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a351d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu G, Bai F, Lin X, Wang Q, Wu Q, Sun S, et al. Association between antihypertensive drug use and the incidence of cognitive decline and dementia: a meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:4368474. doi: 10.1155/2017/4368474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohtsubo T, Shibata R, Kai H, Okamoto R, Kumagai E, Kawano H, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers in hypertensive patients with myocardial infarction or heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hypertens Res. 2019;42(5):641–649. doi: 10.1038/s41440-018-0167-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rodgers JE, Patterson JH. Angiotensin II-receptor blockers: clinical relevance and therapeutic role. Am J Heal Pharm. 2001;58(8):671–683. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/58.8.671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Soto ME, van Kan GA, Nourhashemi F, Gillette-Guyonnet S, Cesari M, Cantet C, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and Alzheimer’s disease progression in older adults: results from the Réseau sur la Maladie d’Alzheimer Français cohort. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(9):1482–1488. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rozzini L, Chilovi BV, Bertoletti E, Conti M, Del Rio I, Trabucchi M, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors modulate the rate of progression of amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21(6):550–555. doi: 10.1002/gps.1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiu W-C, Ho W-C, Lin M-H, Lee H-H, Yeh Y-C, Wang J-D, et al. Angiotension receptor blockers reduce the risk of dementia. J Hypertens. 2014;32(4):938–947. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li ECK, Heran BS, Wright JM. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers for primary hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(8) Available from: https://doi.org//10.1002/14651858.CD009096.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Edwards JD, Ramirez J, Callahan BL, Tobe SW, Oh P, Berezuk C, et al. Antihypertensive treatment is associated with MRI-derived markers of neurodegeneration and impaired cognition: a propensity-weighted cohort study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;59(3):1113–1122. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moran C, Xie K, Poh S, Chew S, Beare R, Wang W, et al. Observational study of brain atrophy and cognitive decline comparing a sample of community-dwelling people taking angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers over time. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;68:1479–1488. doi: 10.3233/JAD-180943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goh KL, Bhaskaran K, Minassian C, Evans SJW, Smeeth L, Douglas IJ. Angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of dementia: cohort study in UK Clinical Practice Research Datalink. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;79(2):337–350. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bohlken J, Jacob L, Kostev K. The relationship between the use of antihypertensive drugs and the incidence of dementia in general practices in Germany. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;70:91–97. doi: 10.3233/JAD-190362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barthold D, Joyce G, Wharton W, Kehoe P, Zissimopoulos J. The association of multiple anti-hypertensive medication classes with Alzheimer’s disease incidence across sex, race, and ethnicity. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0206705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0206705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho JK, Nation DA. Memory is preserved in older adults taking AT1 receptor blockers. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2017;9(1):1–14. doi: 10.1186/s13195-017-0255-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hajjar I, Catoe H, Sixta S, Boland R, Johnson D, Hirth V, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal association between antihypertensive medications and cognitive impairment in an elderly population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(1):67–73. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hajjar I, Brown L, Mack WJ, Chui H. Impact of angiotensin receptor blockers on Alzheimer disease neuropathology in a large brain autopsy series. Arch Neurol. 2012;69(12):1632–1638. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2012.1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glodzik L, Rusinek H, Kamer A, Pirraglia E, Tsui W, Mosconi L, et al. Effects of vascular risk factors, statins, and antihypertensive drugs on PiB deposition in cognitively normal subjects. Alzheimers Dement (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 2016;2:95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.dadm.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beekly DL, Ramos EM, Lee WW, Deitrich WD, Jacka ME, Wu J, et al. The National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) database: the uniform data set. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(3):249–258. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e318142774e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tully PJ, Helmer C, Peters R, Tzourio C. Exploiting drug-apolipoprotein E gene interactions in hypertension to preserve cognitive function: the 3-city cohort study. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2019;20(2):188–194.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2018.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nation DA, Ho J, Yew B, Initiative ADN. Older adults taking AT1-receptor blockers exhibit reduced cerebral amyloid retention. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;50(3):779–789. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–944. doi: 10.1212/WNL.34.7.939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJ, Kawas CH, et al. The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):263–269. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2011.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gohlke P, Weiss S, Jansen A, Wienen W, Stangier J, Rascher W, et al. AT1 receptor antagonist telmisartan administered peripherally inhibits central responses to angiotensin II in conscious rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298(1):62–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gohlke P, Von Kügelgen S, Jürgensen T, Kox T, Rascher W, Culman J, et al. Effects of orally applied candesartan cilexetil on central responses to angiotensin II in conscious rats. J Hypertens. 2002;20(5):909–918. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200205000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Unger T. Inhibiting angiotensin receptors in the brain: possible therapeutic implications. Curr Med Res Opin. 2003;19(5):449–451. doi: 10.1185/030079903125001974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cushman DW, Wang FL, Fung WC, Harvey CM, DeForrest JM. Differentiation of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors by their selective inhibition of ACE in physiologically important target organs. Am J Hypertens. 1989;2(4):294–306. doi: 10.1093/ajh/2.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jouquey S, Mathieu MN, Hamon G, Chevillard C. Effect of chronic treatment with trandolapril or enalapril on brain ACE activity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Neuropharmacology. 1995;34(12):1689–1692. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(95)00146-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jenkins TA, Mendelsohn FA, Chai SY. Angiotensin-converting enzyme modulates dopamine turnover in the striatum. J Neurochem. 1997;68(3):1304–1311. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68031304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tan J, Wang JM, Leenen FHH. Inhibition of brain angiotensin-converting enzyme by peripheral administration of trandolapril versus lisinopril in Wistar rats. Am J Hypertens. 2005;18(2 Pt 1):158–164. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chai SY, Perich R, Jackson B, Mendelsohn FA, Johnston CI. Acute and chronic effects of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors on tissue angiotensin-converting enzyme. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol Suppl. 1992;19:7–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.1992.tb02803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gohlke P, Schölkens B, Henning R, Urbach H, Unger T. Inhibition of converting enzyme in brain tissue and cerebrospinal fluid of rats following chronic oral treatment with the converting enzyme inhibitors ramipril and Hoe 288. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1989;14(Suppl 4):S32–S36. doi: 10.1097/00005344-198906144-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li N-C, Lee A, Whitmer RA, Kivipelto M, Lawler E, Kazis LE, et al. Use of angiotensin receptor blockers and risk of dementia in a predominantly male population: prospective cohort analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5465. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b5465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sink KM, Leng X, Williamson J, Kritchevsky SB, Yaffe K, Kuller L, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and cognitive decline in older adults with hypertension: results from the cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(13):1195–1202. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ohrui T, Tomita N, Sato-Nakagawa T, Matsui T, Maruyama M, Niwa K, et al. Effects of brain-penetrating ACE inhibitors on Alzheimer disease progression. Neurology. 2004;63(7):1324 LP–1321325. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000140705.23869.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chelune GJ, Bornstein RA, Prifitera A, McReynolds P. In: The Wechsler memory scale—revised BT - advances in psychological assessment: volume 7. Rosen JC, Chelune GJ, editors. Boston: Springer US; 1990. pp. 65–99. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weintraub S, Wicklund AH, Salmon DP. The neuropsychological profile of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2012;2(4):a006171. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a006171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Reed BR, Mungas DM, Kramer JH, Ellis W, Vinters HV, Zarow C, et al. Profiles of neuropsychological impairment in autopsy-defined Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular disease. Brain. 2007;130(Pt 3):731–739. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bucks RS. In: Trail-Making Test BT - Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. Gellman MD, Turner JR, editors. New York: Springer New York; 2013. pp. 1986–1987. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, editors. WAIS-R BT - Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. New York: Springer New York; 2011. p. 2668. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, et al. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer’s disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology. 1989;39(9):1159–1165. doi: 10.1212/WNL.39.9.1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roth C. In: Boston Naming Test BT - Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, editors. New York: Springer New York; 2011. pp. 430–433. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Gómez-Rubio V. ggplot2 - Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis (2nd Edition). J Stat Software. 2017;1 B Rev 2 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.jstatsoft.org/v077/b02

- 59.Brooks ME, Kristensen K, Van Benthem KJ, Magnusson A, Berg CW, Nielsen A, et al. glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J. 2017;9(2):378–400.

- 60.van der Wal WM, Geskus RB. ipw: an R package for inverse probability weighting. J Stat Software. 2011;1(13) Available from: https://www.jstatsoft.org/v043/i13

- 61.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, Cushman WC, Dennison-Himmelfarb C, Handler J, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8) JAMA. 2014;311(5):507–520. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE, Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA guideline for the prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127 LP–e12e248. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Verghese PB, Castellano JM, Garai K, Wang Y, Jiang H, Shah A, et al. ApoE influences amyloid-β (Aβ) clearance despite minimal apoE/Aβ association in physiological conditions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(19):E1807–E1816. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1220484110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu C-C, Zhao N, Fu Y, Wang N, Linares C, Tsai C-W, et al. ApoE4 accelerates early seeding of amyloid pathology. Neuron. 2017;96(5):1024–1032.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2017.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nelson L, Gard P, Tabet N. Hypertension and inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease: close partners in disease development and progression! J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;41(2):331–343. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hasan AU, Ohmori K, Hashimoto T, Kamitori K, Yamaguchi F, Ishihara Y, et al. Valsartan ameliorates the constitutive adipokine expression pattern in mature adipocytes: a role for inverse agonism of the angiotensin II type 1 receptor in obesity. Hypertens Res. 2014;37(7):621–628. doi: 10.1038/hr.2014.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goel R, Bhat SA, Hanif K, Nath C, Shukla R. Angiotensin II receptor blockers attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced memory impairment by modulation of NF-κB-mediated BDNF/CREB expression and apoptosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55(2):1725–1739. doi: 10.1007/s12035-017-0450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gebre AK, Altaye BM, Atey TM, Tuem KB, Berhe DF. Targeting renin-angiotensin system against Alzheimer’s disease. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:440. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Drews HJ, Yenkoyan K, Lourhmati A, Buadze M, Kabisch D, Verleysdonk S, et al. Intranasal losartan decreases perivascular beta amyloid, inflammation, and the decline of neurogenesis in hypertensive rats. Neurotherapeutics. 2019;16(3):725–740. doi: 10.1007/s13311-019-00723-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang J, Ho L, Chen L, Zhao Z, Zhao W, Qian X, et al. Valsartan lowers brain beta-amyloid protein levels and improves spatial learning in a mouse model of Alzheimer disease. J Clin Invest. 2007;117(11):3393–3402. doi: 10.1172/JCI31547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Danielyan L, Klein R, Hanson LR, Buadze M, Schwab M, Gleiter CH, et al. Protective effects of intranasal losartan in the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Rejuvenation Res. 2010;13(2–3):195–201. doi: 10.1089/rej.2009.0944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ferrington L, Palmer LE, Love S, Horsburgh KJ, Kelly PA, Kehoe PG. Angiotensin II-inhibition: effect on Alzheimer’s pathology in the aged triple transgenic mouse. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4(2):151–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hemming ML, Selkoe DJ. Amyloid beta-protein is degraded by cellular angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) and elevated by an ACE inhibitor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(45):37644–37650. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508460200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zou K, Yamaguchi H, Akatsu H, Sakamoto T, Ko M, Mizoguchi K, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme converts amyloid β-protein 1–42 (Aβ<sub>1–42</sub>) to Aβ<sub>1–40</sub>, and its inhibition enhances brain Aβ deposition. J Neurosci. 2007;27(32):8628 LP–8628635. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1549-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zou K, Yamaguchi H, Akatsu H, Sakamoto T, Ko M, Mizoguchi K, et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme converts amyloid beta-protein 1-42 (Abeta(1-42)) to Abeta(1-40), and its inhibition enhances brain Abeta deposition. J Neurosci. 2007;27(32):8628–8635. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1549-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zou K, Liu J, Watanabe A, Hiraga S, Liu S, Tanabe C, et al. Aβ43 is the earliest-depositing Aβ species in APP transgenic mouse brain and is converted to Aβ41 by two active domains of ACE. Am J Pathol. 2013;182(6):2322–2331. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2013.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hemming ML, Selkoe DJ, Farris W. Effects of prolonged angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor treatment on amyloid beta-protein metabolism in mouse models of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2007;26(1):273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Liu S, Ando F, Fujita Y, Liu J, Maeda T, Shen X, et al. A clinical dose of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor and heterozygous ACE deletion exacerbate Alzheimer’s disease pathology in mice. J Biol Chem. 2019 ;294(25):9760–9770. 2019/05/09. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31072831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Eckman EA, Adams SK, Troendle FJ, Stodola BA, Kahn MA, Fauq AH, et al. Regulation of steady-state beta-amyloid levels in the brain by neprilysin and endothelin-converting enzyme but not angiotensin-converting enzyme. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(41):30471–30478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605827200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burnham SC, Laws SM, Budgeon CA, Doré V, Porter T, Bourgeat P, et al. Impact of APOE-ε4 carriage on the onset and rates of neocortical Aβ-amyloid deposition. Neurobiol Aging. 2020; Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197458020301871 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82.Rajan KB, Barnes LL, Wilson RS, Weuve J, McAninch EA, Evans DA. Blood pressure and risk of incident Alzheimer’s disease dementia by antihypertensive medications and APOE ε4 allele. Ann Neurol. 2018;83(5):935–944. doi: 10.1002/ana.25228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kim IY, Grodstein F, Kraft P, Curhan GC, Hughes KC, Huang H, et al. Interaction between apolipoprotein E genotype and hypertension on cognitive function in older women in the Nurses’ Health Study. PLoS One. 2019;14(11):e0224975. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.de Oliveira FF, Chen ES, Bertolucci MCS, PHF Pharmacogenetics of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors in patients with Alzheimer's disease Dementia. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2018;15:386–398. doi: 10.2174/1567205014666171016101816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wang B, Jin F, Yang Z, Lu Z, Kan R, Li S, et al. The insertion polymorphism in angiotensin-converting enzyme gene associated with the APOE epsilon 4 allele increases the risk of late-onset Alzheimer disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;30(3):267–271. doi: 10.1385/JMN:30:3:267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ouk M, Wu C-Y, Rabin JS, Edwards JD, Ramirez J, Masellis M, et al. Associations between brain amyloid accumulation and the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors versus angiotensin receptor blockers. Neurobiol Aging. 2021;100:22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2020.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Swardfager W, Black SE. Coronary artery calcification: a canary in the cognitive coalmine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67:1023–1026. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lucatelli JF, Barros AC, da Silva VK, da Silva Machado F, Constantin PC, Dias AAC, et al. Genetic influences on Alzheimer’s disease: evidence of interactions between the genes APOE, APOC1 and ACE in a sample population from the south of Brazil. Neurochem Res. 2011;36(8):1533–1539. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0481-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.O’Caoimh R, Healy L, Gao Y, Svendrovski A, Kerins DM, Eustace J, et al. Effects of centrally acting angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors on functional decline in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;40(3):595–603. doi: 10.3233/JAD-131694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yamada K, Horita T, Takayama M, Takahashi S. Effect of a centrally active angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor , perindopril , on cognitive performance in chronic cerebral hypo-perfusion rats. Brain Res. 2011;1421:110–120. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li Z, Bains JS, Ferguson AV. Functional evidence that the angiotensin antagonist losartan crosses the blood-brain barrier in the rat. Brain Res Bull. 1993;30(1–2):33–39. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(93)90036-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bui JD, Kimura B, Ian PM. Losartan potassium, a nonpeptide antagonist of angiotensin II, chronically administered p.o. does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier. Eur J Pharmacol. 1992;219(1):147–151. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90593-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hazlewood RJ, Chen Q, Clark FK, Kuchtey J, Kuchtey RW. Differential effects of angiotensin II type I receptor blockers on reducing intraocular pressure and TGFβ signaling in the mouse retina. PLoS One. 2018;13(8):e0201719. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Villapol S, Saavedra JM. Neuroprotective effects of angiotensin receptor blockers. Am J Hypertens. 2014;28(3):289–299. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpu197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Noda A, Fushiki H, Murakami Y, Sasaki H, Miyoshi S, Kakuta H, et al. Brain penetration of telmisartan, a unique centrally acting angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, studied by PET in conscious rhesus macaques. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39(8):1232–1235. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shimizu K, Takashima T, Yamane T, Sasaki M, Kageyama H, Hashizume Y, et al. Whole-body distribution and radiation dosimetry of [11C] telmisartan as a biomarker for hepatic organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP) 1B3. Nucl Med Biol. 2012;39(6):847–853. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Montagne A, Nation DA, Sagare AP, Barisano G, Sweeney MD, Chakhoyan A, et al. APOE4 leads to blood–brain barrier dysfunction predicting cognitive decline. Nature. 2020;581(7806):71–76. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2247-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Piotrowicz K, Prejbisz A, Klocek M, Topór-Mądry R, Szczepaniak P, Kawecka-Jaszcz K, et al. Subclinical mood and cognition impairments and blood pressure control in a large cohort of elderly hypertensives. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2016;17(9):864.e17–864.e22. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2016.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Participant inclusion/exclusion flowchart, APOE ε4 carrier vs. non-carrier plots, and tables for secondary cognitive outcomes.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in the current study were obtained from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC). For further information on access to the database, please contact NACC (contact details can be found at https://www.alz.washington.edu/).